Abstract

Studies of the multifunctional protein p11 (also known as S100A10) are shedding light on the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying depression. Here we review data implicating p11 in both the amplification of serotonergic signaling and the regulation of gene transcription. We summarize studies demonstrating that the levels of p11 are regulated in depression and by antidepressant regimens and, conversely, that p11 regulates depression-like behaviors and/or responses to antidepressants. Current and future studies of p11 may provide a molecular and cellular framework for the development of novel antidepressant therapies.

Introduction

The lifetime risk for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is 20–25 % for women and 7–12% for men1. Despite several decades of intense research, understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease is limited. Treatments remain inadequate and, when effective, delayed in their onset and afflicted with side effects1. Thus, there is a major unmet medical need for more effective therapies. To that end, a better understanding of the pathogenesis of MDD, as well as of the actions of antidepressants, is needed. The most commonly used class of antidepressants is the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which, by elevating extracellular levels of serotonin, activate multiple pre- and post-synaptic serotonin receptors. In an effort to find endogenous modulators of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) receptor function, we searched for interacting partners of distinct serotonin receptors using a yeast two-hybrid screen2. These experiments showed that 5-HT receptor 1B (5-HT1BR), 5-HT1DR and 5-HT4R all interacted with a protein known as p11 (also known as S100A10, nerve growthfactor-induced protein 42C, calpactin I light chain, and annexin II light chain)2,3. Studies of transfected cell lines showed that overexpression of p11 increased the levels of 5-HT1BR and 5-HT4R at the cell surface, resulting in enhanced effects of these receptors on cell signaling2,3. This indicated that p11, like SSRIs, potentiates serotonin neurotransmission.

P11 is a member of the S100 EF-hand protein family. S100 proteins are small acidic proteins (10–12 kDa) and constitute the largest subfamily of EF-hand proteins, with at least 25 members4. S100 proteins exist as symmetrical homo- and hetero-dimers, with each monomer containing two EF-hand motifs which bind calcium. A unique feature of p11 is that it contains mutations in both of the calcium-binding sites, making it calcium insensitive. p11 was initially identified within a heterotetrameric complex that it forms with annexin A25. Prior studies have also shown that p11 interacts with ion channels (including sodium channel protein type 10 subunit alpha (Nav1.8), potassium channel subfamily K, acid-sensing ion channels, transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 5) and enzymes, such as tissue plasminogen activator and phospholipase A26,7.

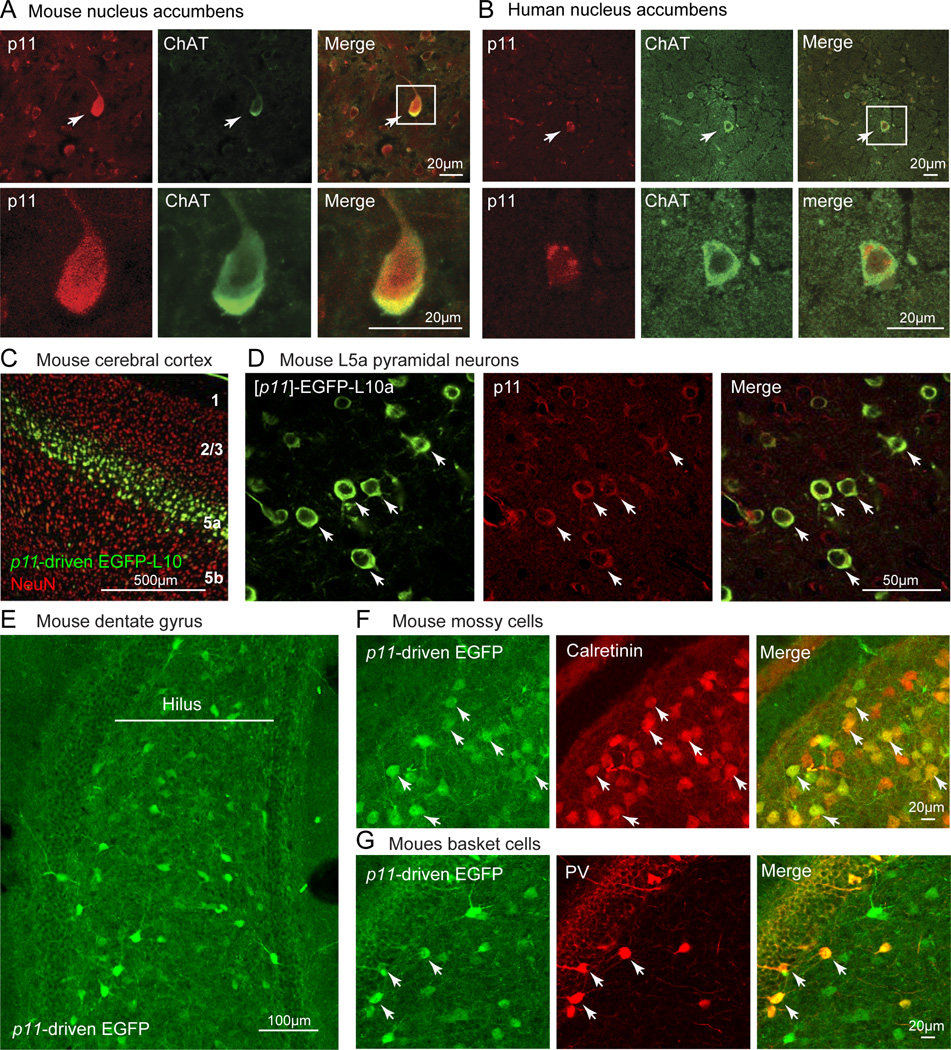

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization studies in mouse and human brainrevealed that p11 is expressed in interneurons GABAergic and cholinergic interneurons and in monoaminergic, cholinergic, glutamatergic and GABAergic projection neurons2,3,8,9. P11 is not restricted to neurons, but is also found in, for example, epithelial and endothelial cells7. Interestingly, p11 is expressed in several brain regions implicated in the pathophysiology of depression, including the nucleus accumbens (Fig 1A, B), cerebral cortex (Fig 1C, D) and hippocampus8,10,11 (Fig 1E–G). These results prompted us to evaluate the possibility that altered p11 levels or functioning underlie aspects of depression-like states and that p11 regulates responses to antidepressants.

Figure 1. p11 expression in brain areas relevant to depression and antidepressant responses.

(A, B) Immunohistochemical experiments illustrating that p11 is enriched in cholinergic (that is, choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-expressing) neurons in the nucleus accumbens in the (A) mouse and (B) human brain. (C, D) Cortical expression of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) fused with L10a controlled by the p11 promotor is shown with a neuronal marker (NeuN) in a low magnified image (C) and immunohistochemistry with EGFP-specific antibodies and antibodies directed against endogenous p11 show that p11 is highly enriched in mouse layer 5a pyramidal neurons (D). (E) In the dentate gyrus, cell bodies expressing p11 promoter-driven EGFP are enriched in the hilus. (F, G) Within the dentate gyrus, p11 promoter-driven EGFP co-localizes with both (F) calretinin (CRT), a marker of excitatory hilar mossy cells, and (G) parvalbumin (PV), a marker of inhibitory basket cells. Parts A, B are modified from REF. 8; Parts C, D are modified from REF. 10; Parts E, F, G are modified from REF. 11.

Of clinical and translational relevance, p11 mRNA and protein are down-regulated in the anterior cingulate cortex and the ventral striatum (specifically, the nucleus accumbens) from depressed individuals2,12 and in helpless H/Rouen mice, a genetic animal model of depression2. Studies in human suicide victims have also found reductions of p11 mRNA in hippocampus and amygdala, indicating an important role of p11 in multiple regions implicated in depression pathophysiology13. Conversely, antidepressants of several distinct categories — (SSRIs; tricyclic antidepressants; monoamine oxidase inhibitors) — as well as electroconvulsive treatment, increase p11 expression in frontal cortex and hippocampus of mice and rats2,14.

Here, we review the current state of knowledge of the regulation of p11 expression. We also summarize the behavioral phenotypes in constitutive and conditional p11 knock-out mice and in mice with virus-mediated knockdown or overexpression of p11. Finally, we also review mechanisms of p11 action, with an emphasis on its interaction with 5-HT receptors, annexin A2 and SMARCA3, and its role in depression and in mediating therapeutic responses to antidepressants.

Regulation of p11 levels

Neurotransmitters and growth factors

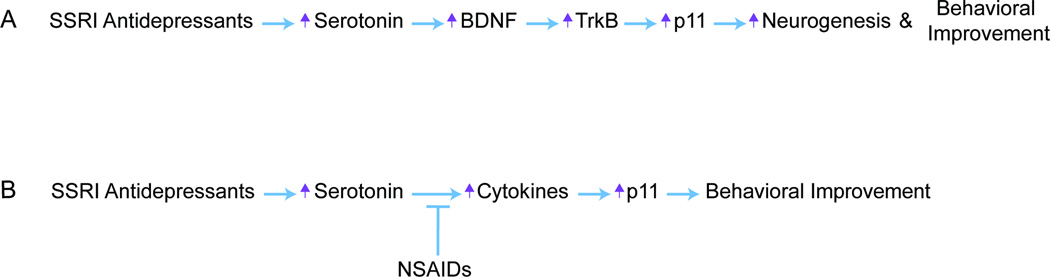

Chronic treatment with any of several antidepressants that exert their therapeutic actions by elevating extrasynaptic concentrations of monoamines increases p11 mRNA levels in the cortex and hippocampus of mice2,14. In addition to monoamine-based antidepressants, treatment with the dopamine precursor, L-DOPA, also induces p11 mRNA and protein levels15. The mechanisms underlying the monoamine-regulated increase of p11 need to be more thoroughly characterized, but they appear to involve an up-regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) signaling14. Accordingly, antidepressant regimens also regulate the levels of BDNF in cortex and hippocampus16. Studies using neuronal cultures and mutant mice overexpressing BDNF have provided evidence that signaling through the trkB receptor and ERK-mediated signaling pathway appears to mediate the induction of p11 by this neurotrophin14. Conversely, p11 mRNA and protein levels are reduced in striatum and cortex from BDNF KO mice14. Serotonin induces p11 more potently in neuronal cultures from wildtype than BDNF KO mice14. These findings suggest that effects of neurotransmitters on p11 levels may, at least in part, be mediated by changes in BDNF (Fig 2A). It is likely that additional growth factors regulate p11 levels in neurons. It has been shown, for example, that nerve growth factor (NGF) potently stimulates p11 expression in dorsal root ganglia in vivo17 and PC12 cells in vitro18.

Figure 2. Pathways by which p11 mediates behavioral responses to antidepressants.

(A) SSRI Antidepressants increase BDNF/TrkB-mediated regulation of p11, which subsequently stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis and behavioral improvement. (B) SSRI Antidepressants increase brain levels of certain cytokines, which in turn increase levels of p11, the effect of which produces behavioral antidepressant responses. This pathway can be antagonized by NSAID coadministration.

Cytokines and glucocorticoids

Intraperitoneal injections of cytokines, including interferon γ (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), increase p11 protein levels in mouse frontal cortex19. Sub-chronic administration of another cytokine, IL-1b, in a regimen that induces sickness behavior, also increases p11 mRNA levels in mouse prefrontal cortex and hippocampus20. Using p11 as a molecular read-out for antidepressant responses and noting its regulation by cytokines, we also found that anti-inflammatory drugs reduce the efficacy of SSRI antidepressants in rodents and humans. In mice, when anti-inflammatory drugs are chronically co-administered with an SSRI antidepressant, p11 levels are not increased and the behavioral response to the SSRI is blocked19 (Fig 2B). Anti-inflammatory drugs alone had no effect on depression-related behaviors in our experiments. Although cytokines appear to be potent regulators of p11, it is not yet clear whether they directly increase p11 production via cytokine receptor-induced signaling pathways or act indirectly by affecting the production and signaling of neurotrophic factors, such as BDNF.

There are two seeming contradictions between the p11 studies with cytokines and the clinical literature; however, there are several possible explanations that will require further experimental investigation. First, clinical studies have shown that peripheral administration of certain cytokines (IFNα) and increased inflammation cause depression symptoms in humans21. The specific cytokines (and cell types from which they are released) that increase p11 have not been fully characterized, especially in humans. It is possible that the cytokines mediating depression symptoms in human are a distinct group from those that mediate the rise in p11 levels in the brain. If the same cytokines are involved in both processes, the discrepancy may be due to differences in the local concentration of the cytokine as there is evidence that depending on the dose and duration of cytokine delivery, a given cytokine (such as IL1b) can either increase or decrease levels of neurotrophins, having a trophic or toxic effect on downstream target cells22. Secondly, there is a clinical literature supporting the use of anti-inflammatory agents to augment the efficacy of noradrenergic antidepressants (NRIs)23, whereas our work demonstrates in mice and humans that anti-inflammatory drugs antagonize the efficacy of serotonergic antidepressants (SSRIs). In fact, analysis of the COMED clinical trial has indicated that concomitant NSAID use reduces the efficacy of SSRI antidepressants while augmenting the response to other classes of antidepressant drugs24. It is therefore important to emphasize the specificity of the antagonism between anti-inflammatory agents and the SSRI class of antidepressants. It may turn out that this antagonism may be overcome by increasing the dose of SSRI antidepressant or by taking advantage of the other available antidepressant drug options.

In addition, one study has shown that exposure to inescapable footshock stress or administration of the synthetic glucocorticoid dexamethasone increases p11 mRNA levels in the prefrontal cortex by activating glucocorticoid response elements in the p11 promoter25. Based on the depression-like phenotype of p11 KO mice, the expectation would be that stress, a factor that can precipitate or worsen depression, would lower p11 levels. The observed increase in p11 levels in response to stress or glucocorticoid exposure could be a physiological response to counteract depression symptoms by elevating p11 levels and thus sensitivity to serotonin. The above-mentioned data have indicated that p11 is regulated by BDNF, cytokines and glucocorticoids, factors critically implicated in mood regulation. However, more detailed studies are required to understand the role of paradoxical induction of p11 by stress or pro-inflammatory cytokines and to formulate a coherent molecular model on the interaction of p11 with these factors in depression and antidepressant actions.

Behaviors in p11 mouse models

Studies in mice lacking p11 have shown that p11 plays a crucial role in regulating depression-like behaviors and responses to SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants. Constitutive p11 KO mice, which lack p11 in the whole brain and body, show a depression-like behavioral phenotype in several well-established models that measure behavioral despair (e.g., forced swim and tail suspension tests) or anhedonia (e.g., sucrose preference test)2,14. P11 KO mice also show a deficit in emotional learning, as indicated by impaired performance in the passive avoidance task26. In addition to the observed depressive-like phenotype in these tests, constitutive p11 KO mice show reduced responses to antidepressant administration in the forced swim, tail suspension and novelty suppressed feeding tests2,14,27. Together, these behavioral studies indicate that constitutive loss of p11 is sufficient to induce a depression-like state and that p11 is crucial for antidepressant responsiveness.

The nucleus accumbens has been identified as a critical region for the depression-like behaviour in p11 KO mice8,12. Specifically, reducing p11 expression only in the nucleus accumbens by virus-mediated RNAi was sufficient to recapitulate the depressive-like behavioral phenotype observed in the constitutive p11 KO mice12. In wild-type mice, p11 is enriched 30-fold in accumbal cholinergic interneurons compared to neighboring cell-types8 (Fig 1A, B), and removal of p11 from these cholinergic neurons caused a depressive-like behavioral phenotype8. Conversely, virus-mediated overexpression of p11 in accumbal cholinergic interneurons, but not in those of the dorsal striatum, was sufficient to reverse the depression-like phenotype of constitutive p11 KO mice8. Interestingly, removal of accumbal p11 did not reduce the effect of SSRI antidepressants on immobility in the tail suspension test8,12. Thus, although accumbal p11 seems to be crucial in the regulation of mood-related behaviours, it does not seem to mediate antidepressant responses. Instead, cortical expression of p11 appears to be required for responses to antidepressants in rodent behavioral models. Chronic antidepressant treatment increased p11 levels in cortex and hippocampus2,10,14, and increased 5-HT4R mRNA in p11-containing cortical neurons in mice10. Removal of p11 from pyramidal projection neurons in cortical layer 5A is associated with reduced behavioral responses and ablated the up-regulation of 5-HT4Rs induced by SSRI treatment, but did not reveal a baseline depression-like phenotype10.

Molecular and cellular actions of p11

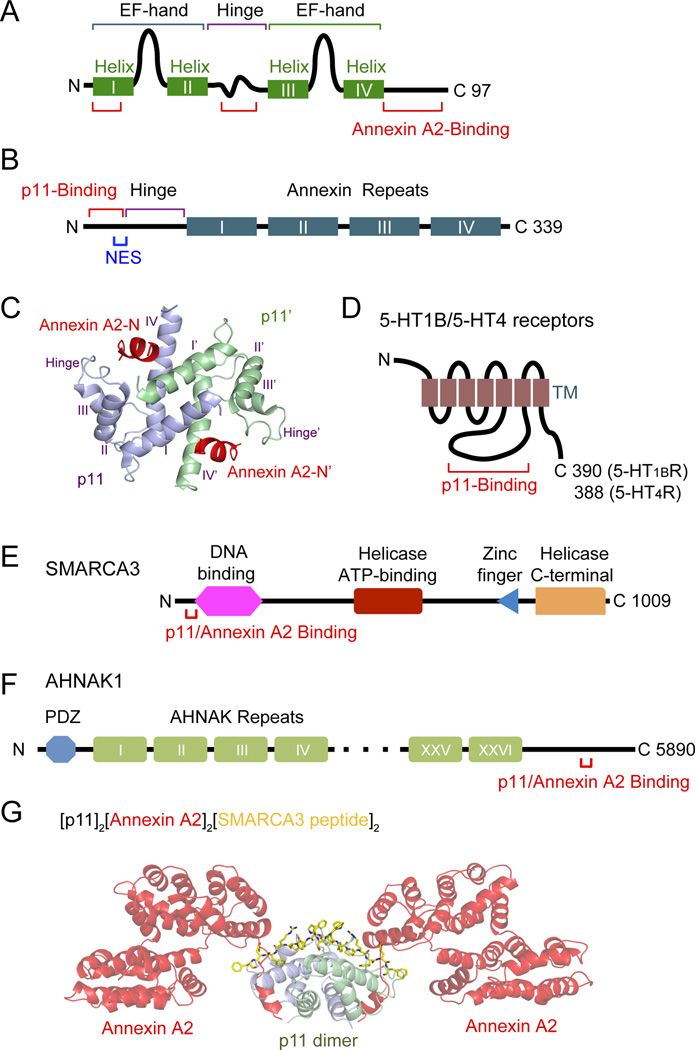

P11 forms a tight non-covalent dimer through Helix I and Helix IV (Fig 3A). p11 was discovered as an interacting partner for Ca2+/lipid-binding protein annexin A25. Helix I, hinge and C-terminus of p11 participate in annexin A2 binding. Annexin A2 is a member of the annexin multi-gene family. The N-terminal 12 amino acids of annexin A2 that form an amphiphatic α-helix are sufficient for p11 binding (Fig 3B). Annexin A2 also has a nuclear export signal (NES) motif in the N-terminus, and four annexin repeat domains. The x-ray crystal structure of p11 in complex with the N-terminal region from annexin A2 showed that the four helices from each monomer are arranged in an antiparallel manner, and that the p11 dimer contains two identical annexin A2-binding sites (a hydrophobic cleft formed by the C-terminal region from one monomer and the Helix I from the other monomer), forming a heterotetramer28,11 (Fig 3C). P11 can be targeted to membranes via complex formation with annexin A2 probably in a Ca2+-regulated manner because the annexin A2 subunit requires Ca2+ for efficient membrane binding29.

Figure 3. Protein structures of p11 and p11 binding proteins.

(A) P11 is composed of two non-calcium binding EF-hand motifs and four α-helices. Helix I, hinge and C-terminus of p11 participate in annexin A2 binding. (B) Annexin A2 is composed of p11 binding motif (aa 2–12) and NES motif in the N-terminus, and four annexin repeat domains, each of which is 70 amino acids long and composed of five α-helices. (C) Ribbon representation of x-ray crystal structure of [p11]2 [N-terminal peptide of annexin A2]2. (D) 5-HT1B and 5-HT4 receptors, G-protein coupled receptors. The third intracellular loop is the binding region of p11. (E) SMARCA3 domain structure, including DNA-binding, helicase ATP-binding, RING-type Zinc finger, and helicase C-terminal domains. P11/annexin A2 binding motif is located in the N-terminus (aa 34–39). (F) AHNAK1 is a 700kDa protein with a PDZ domain in N-terminus and a central region composed of 128-amino acid unit, repeated 26 times. P11/annexin A2 binding motif resides in C-terminal region (aa5663–5668). (G) X-ray crystal structure of SMARCA3 peptide (yellow) in stick representation bound to full-length annexin A2 (red) and p11 (purple and cyan) in ribbon representation. Part C is modified from REF. 11, 28; Part G is modified from REF. 11.

P11 interacts with serotonin receptors 5-HT1BR, 5-HT1DR and 5-HT4Rs2,3 (Fig 3D). The interaction was initially observed in yeast two hybrid screening in which the third intracellular loops of 5-HTRs were used as baits. The precise p11 binding motif in 5-HTRs and the role of annexin A2 in the interaction between p11 and 5-HTRs remain to be studied.

A recent study identified a chromatin-remodeling factor, SMARCA3 (SWI/SNF-related, matrix-associated, actin-dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily A, member 3; also known as helicase-like transcription factor) as a binding protein of the p11/annexin A2 heterotetramer28. Other binding partners of the heterotetramer were identified as AHNAK1 and SPT6 (suppressor of Ty 6 homolog S. cerevisiae)11. A p11 binding motif is located in the N-terminus of SMARCA311 (Fig 3E) This motif is highly homologous to the p11-binding motif found in the C-terminus of AHNAK1 (Fig 3F). X-ray crystal structures of p11/annexin A2 in complex with the motif peptides found in SMARCA3 or AHNAK1 revealed that p11 and annexin A2 cooperate to create a unique binding pocket for SMARCA3 or AHNAK1 motif peptide (Fig 3G for the complex with SMARCA3 peptide)11. The complexes with SMARCA3 peptide and AHNAK1 peptide share very similar intermolecular contacts and recognition principles.

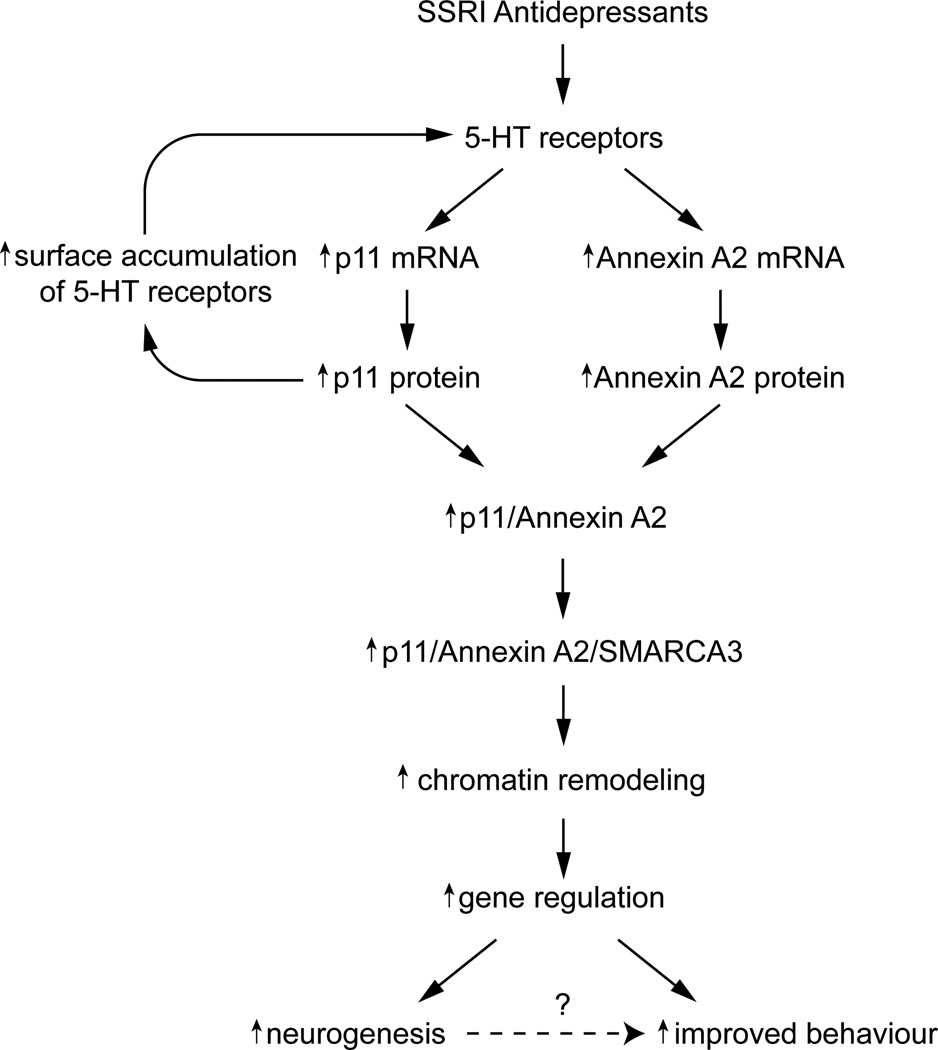

By virtue of these interactions, p11 mediates antidepressant actions both at the plasma membrane and in the nucleus, as described below (Fig 4). It is also possible that p11 regulates antidepressant actions by virtue of its interactions with other binding proteins, including the ion channels and enzymes mentioned in the introduction, but this remains to be studied.

Figure 4. How SSRI antidepressants may regulate interactions between serotonin receptors, p11, annexinA2 and SMARCA3.

Both p11 and annexin A2 mRNA and protein levels are up-regulated in hippocampus and cortex after chronic SSRI administration, and this upregulation is likely to be mediated by 5-HT receptors. p11 in turn increases the levels of 5-HT1B/4R at the plasma membrane, providing an amplification mechanism for antidepressant actions. The heterotetrameric p11/annexin A2 complex binds to 2 molecules of SMARCA3 and the heterohexameric complex is then targeted to the nuclear matrix. The localization of the complex in the nuclear matrix is likely mediated by annexin A2 which is known to interact with phospholipids and actins. p11/annexin A2/SMARCA3 complex remodels chromatin and regulates gene transcription. This regulation appears to underlie increased hippocampal neurogenesis and antidepressant behavioural responses observed after chronic SSRI treatment. Both p11 KO mice and SMARCA3 KO mice exhibit reduced neurogenic and behavioral responsiveness to SSRI administration. The question mark indicates that the possible role of neurogenesis in behavioral improvement has not been rigorously demonstrated.

Role of p11 in 5-HT1BR and 5-HT4R function

In mice, p11 is co-localized with 5-HT1BR and/or 5-HT4R in many cell types of the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and nucleus accumbens3,9. The third intracellular loops of 5-HT1BR and 5-HT4R interact with p112,3. p11 increases the surface expression of 5-HT1BR and 5-HT4R and potentiates the effects of 5-HT on cAMP signaling in cell lines transfected with 5-HT1BR or 5-HT4R2,3. Likewise, radioligand binding to the 5-HT1BR is increased in mouse brain after virus-mediated overexpression of p1112. Conversely, radioligand binding at 5-HT1BR and 5-HT4R is reduced in p11 KO mice2,3. These data indicate that p11 promotes cell surface expression of certain serotonin receptors in neurons (Fig 4), but the precise mechanisms are yet to be determined.

In primary neuronal cultures from mouse cortex or striatum, p11 potentiated the effects of 5-HT1BR and 5-HT4R activation on calcium influx and ERK1/2 signaling2,3,12. Experiments in striatal slices demonstrated that inhibitory actions of a 5-HT1BR agonist on the levels of phospho-synapsin I (a presynaptic protein that has a role in vesicle docking and neurotransmitter release) and of serotonin on corticostriatal glutamatergic synaptic transmission, are dependent upon p112. 5-HT1BR and 5-HT4R oppositely regulate several intracellular signaling pathways and it could be assumed that actions of serotonin on p11 would be cancelled out. However, at least in some brain regions, 5-HT1B/DR and 5-HT4R may regulate p11 in distinct non-overlapping cell types. At the individual cellular level, this may cause opposite effects on p11 regulation, but at the circuitry level, it may lead to additive actions on output function. Such a scenario has been described for dopamine D1 versus D2 receptors in the basal ganglia. D1 and D2 receptors signal oppositely to cAMP, but are segregated in striatonigral versus striatopallidal neurons. Through their actions in the direct and indirect pathways of the basal ganglia, the net outcome is a synergistic inhibition of substantia nigra pars reticulata30.

Further evidence for an interaction between p11 and 5-HT receptors has come from behavioral studies in p11 KO mice. In these mice, the antidepressant-like effects of 5-HT1BR31 and 5-HT4R agonists32, but not of 5-HT6R agonists33, in the tail suspension test and forced swim test were reduced compared to wild-type mice2,3. The anxiolytic effects of 5-HT1BR and 5-HT4R agonists on thigmotaxis seen in the open field in wild-type mice were also reduced in p11 KO mice2,3. These findings suggest that p11, by virtue of its ability to promote accumulation of 5-HT receptors at the cell surface, serves as an amplification mechanism for 5-HT receptor-mediated actions (Fig 4). Initial studies also implicate p11 in regulating serotonin-mediated effects on cognitive processing with relevance for depression. 5-HT1BR agonists had opposite effects on emotional learning in the passive avoidance test in wild-type and p11 KO mice, impairing it in the former strain but enhancing it in the latter26. Studies with viral overexpression of p11 in the dentate gyrus and CA1 regions of the hippocampus of p11 KO mice suggested that hippocampus is the region mediating the effects of p11 on 5-HT1BR-mediated emotional learning. These data point to an important role for p11 in tuning 5-HT1BR-mediated regulation of emotional processing in hippocampus, but the cell types involved in these effects remain to be identified.

Role of p11 in SMARCA3 function

p11 forms a heterotetramer with annexin A2. Both p11 and annexin A2 are up-regulated in hippocampus after chronic SSRI administration in wild-type mice11 (Fig 4). In addition, the heterotetrameric form of p11/annexin A2 increases after antidepressant administration11. In contrast to p11 and annexin A2, the levels of SMARCA3 protein and mRNA were not altered after treatment with SSRI. However, chronic SSRI administration increased the ternary complex of p11/annexin A2/SMARCA3. Thus, p11 and annexin A2 induction facilitates the assembly of the p11/annexin A2/SMARCA3 complex11.

SMARCA3 belongs to the family of SWI/SNF (switch/sucrose nonfermentable) proteins that remodel chromatin using energy released through ATP hydrolysis34. Transcription factors such as Sp1, Sp3, Egr1, and cRel are known to bind to the C-terminus of SMARCA3, thereby being delivered to the relevant gene promoters34. By forming a complex with p11/annexin A2, SMARCA3 promotes its own localization to the nuclear matrix fraction11, the subnuclear region where critical nuclear events, such as gene expression, replication and repair processing, occur35. A previous study36 and our unpublished study indicate that p11 and annexin A2 shuttle between cytoplasm and nucleus, and that the nuclear export signal (NES) located in the N-terminus of annexin A2 (Fig 3B) plays a critical role in the nuclear export of p11 as well as annexin A2. Specifically, annexin A2 has been shown to associate with the nuclear matrix37, which is composed of nuclear lamins, actin and actin-related proteins, and phospholipids35,38, and the subnuclear targeting of SMARCA3 is likely controlled by intrinsic phospholipid- and actin-binding properties of annexin A229. SMARCA3 interaction with p11/annexin A2 also increases its DNA-binding affinity and transcriptional activity11. Like most chromatin remodeling complexes, SMARCA3 displays DNA- and/or nucleosome-dependent ATPase activity39,40. The enhanced DNA binding likely leads to SMARCA3 activation to initiate ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling of target genes, and to recruit transcription factors bound to the C-terminal domain of SMARCA3 to the specific locus of the genomic DNA.

Mice with a constitutive absence of SMARCA3 show reduced responses to SSRIs in tests of anhedonia and novelty suppressed feeding11, but these mice have no baseline depression-like or anxiety phenotype11. The p11/annexin A2/SMARCA3 complex appears, thus, to be an important mediator of antidepressant responses.

p11 regulates antidepressant-induced neurogenesis

In the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampus of both rodents and humans, neurogenesis has been demonstrated to continue past development into adulthood41,42. This discovery has generated an immense interest in possible functional implications of adult neurogenesis in both normal and pathological states. Interestingly, nearly all types of conventional antidepressant treatments induce adult hippocampal neurogenesis43,44. Some, but not all, reports suggest that adult neurogenesis mediates at least some of the actions of antidepressants. For example, ablation of neurogenesis in mice blocks the behavioral effect of fluoxetine in the novelty suppressed feeding task44. The stimulatory effects of fluoxetine on cell proliferation, neurogenesis, cell survival, and cell apoptosis in the hippocampus are reduced in p11 KO mice27. Chronic fluoxetine-induced proliferation of neural progenitors is abolished and survival of newborn neurons is partially reduced in constitutive SMARCA3 KO mice11. These findings suggest that the p11/annexin A2/SMARCA3 complex contributes to multiple stages of antidepressant-stimulated neurogenesis. The complex probably acts in a non-cell autonomous fashion, however, as p11 expression is increased by chronic fluoxetine in the hippocampus, specifically in GABAergic basket cells and glutamatergic hilar mossy cells in the dentate gyrus (in both of which p11 is colocalized with SMARCA328), but not in the newborn cells of this region11.

Conclusions and future directions

The findings summarized here suggest an important role for p11 in the pathophysiology of depression and in mediating therapeutic actions of monoamine-based antidepressant regimens. Future studies should examine the possible involvement of p11 in mediating therapeutic responses to other antidepressant approaches, such as deep brain stimulation of the cingulate cortex45 or treatment with ketamine, a fast-acting antidepressant, and related glutamatergic substances46. It is intriguing that viral transduction of p11 to neurons in the nucleus accumbens of constitutive p11 KO mice abolishes their depression-like phenotype in several tests, including sucrose consumption, often referred as an index of hedondic drive8, 12. Ongoing studies in non-human primates are being carried out to determine whether gene transfer aimed at overexpressing p11 in the nucleus accumbens is safe and might serve as a therapy in depressed individuals. Studies in cell type-specific p11 KO mice have defined distinct cell types in which p11 is implicated in depression-like states and in therapeutic responses to antidepressants, and further studies of these mouse lines, combined with optogenetic, viral and/or tracing approaches, should shed light on brain circuitries perturbed in depression. p11 is expressed in peripheral blood cells and ongoing work should establish whether peripheral p11 expression can serve as a biomarker of depression and/or responsiveness to antidepressant treatment. Two relatively small studies have failed to find any association of the p11 gene with depression47,48. However, given the difficulties in finding reproducible and robust association between single-nucleotide polymorphisms and depression49, more detailed studies are probably necessary to determine whether polymorphisms in the p11 gene are associated with subgroups of depressed patients or treatment responsivity.

From a mechanistic standpoint, more detailed studies on the regulation of 5-HT receptor trafficking by p11 and annexin A2 may reveal valuable and novel therapeutic targets. It will also be of importance to identify the genes activated by the p11/annexin A2/SMARCA3 chromatin remodeling complex and to determine which of these are involved in mediating therapeutic responses to antidepressants.

Finally, we recently examined a large clinical data-set collected to assess antidepressant efficacy (the STAR*D trial) and found that depressed individuals who reported taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) while taking an SSRI (citalopram) had a lower remission rate than those who did not report NSAID use19. This work offers a possible explanation for why a considerable number of patients with depression do not respond to SSRI antidepressants. It should be noted that other classes of antidepressants are not negatively affected by anti-inflammatory treatments, offering a treatment alternative to affected patients. It would be interesting in future work to study how antidepressants, depression-like states and stress regulate pro- versus anti-inflammatory cytokine levels and to correlate these results with regulation of p11 and behavior.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the important contributions of Drs Nathaniel Heintz, Eric Schmidt, Dinshaw Patel, Pu Gao and Michael Kaplitt to our understanding of the various functions of p11. This work was supported by the The Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Research Foundation (P.S. and P.G.), W81XWH-09-1-0402 (P.G.), NIH MH090963 (P.G.), NIDA1RC2DA028968 (P.G.), The JPB Foundation (P.G.), W81XWH-09-1-0392 (Y.K.), W81XWH-09-1-0401 (J.L.W.-S.), and Swedish Research Council (P.S.). We apologize to the authors of the many interesting studies that could not be included owing to space constraints.

References

- 1.Belmaker RH, Agam GN. Major depressive disorder. New Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:55–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra073096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svenningsson P, et al. Alterations in 5-HT1B receptor function by p11 in depression-like states. Science. 2006;311:77–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1117571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warner-Schmidt JL, et al. Role of p11 in cellular and behavioral effects of 5-HT4 receptor stimulation. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:1937–1946. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5343-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marenholz I, Heizmann CW, Fritz G. S100 proteins in mouse and man: from evolution to function and pathology (including an update of the nomenclature) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;322:1111–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerke V, Weber K. The regulatory chain in the p36-kd substrate complex of viral tyrosine-specific protein kinases is related in sequence to the S-100 protein of glial cells. EMBO. J. 1985;4:2917–2920. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04023.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svenningsson P, Greengard P. p11 (S100A10)--an inducible adaptor protein that modulates neuronal functions. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2007;7:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rescher U, Gerke V. S100A10/p11: family, friends and functions. Pflugers Arch. 2008;455:575–582. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warner-Schmidt JL, et al. Cholinergic interneurons in the nucleus accumbens regulate depression-like behavior. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:11360–11365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209293109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egeland M, Warner-Schmidt J, Greengard P, Svenningsson P. Co-expression of serotonin 5-HT(1B) and 5-HT(4) receptors in p11 containing cells in cerebral cortex, hippocampus, caudate-putamen and cerebellum. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt EF, et al. Identification of the cortical neurons that mediate antidepressant responses. Cell. 2012;149:1152–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh YS, et al. SMARCA3, a chromatin remodeling factor, is required for p11-dependent antidepressant action. Cell. 2013;152:831–843. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander B, et al. Reversal of depressed behaviors in mice by p11 gene therapy in the nucleus accumbens. Science Transl. Med. 2010;2:54ra76. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anisman H, et al. Serotonin receptor subtype and p11 mRNA expression in stress-relevant brain regions of suicide and control subjects. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008;33:131–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warner-Schmidt JL, et al. A role for p11 in the antidepressant action of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X, Andren PE, Greengard P, Svenningsson P. Evidence for a role of the 5-HT1B receptor and its adaptor protein, p11, in L-DOPA treatment of an animal model of Parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2163–2168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711839105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saarelainen T, Hendolin P, Lucas G, Koponen E, Sairanen M, MacDonald E, Agerman K, Haapasalo A, Nawa H, Aloyz R, Ernfors P, Castrén E. Activation of the TrkB neurotrophin receptor is induced by antidepressant drugs and is required for antidepressant-induced behavioral effects. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:349–357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00349.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okuse K, et al. Annexin II light chain regulates sensory neuron-specific sodium channel expression. Nature. 2002;417:653–656. doi: 10.1038/nature00781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masiakowski P, Shooter EM. Nerve growth factor induces the genes for two proteins related to a family of calcium-binding proteins in PC12 cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:1277–1281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warner-Schmidt JL, et al. Antidepressant effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are attenuated by antiinflammatory drugs in mice and humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:9262–9267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104836108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anisman H, Gibb J, Hayley S. Influence of continuous infusion of interleukin-1beta on depression-related processes in mice: corticosterone, circulating cytokines, brain monoamines, and cytokine mRNA expression. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199:231–244. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1166-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raison CL, Miller AH. Is depression an inflammatory disorder? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13:467–475. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0232-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song C, Zhang Y, Dong Y. Acute and subacute IL-1β administrations differentially modulate neuroimmune and neurotrophic systems: possible implications for neuroprotection and neurodegeneration. J Neuroinflam. 2013;10:59–74. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller N, et al. The cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib has therapeutic effects in major depression: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled, add-on pilot study to reboxetine. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:680–684. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trivedi MH, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use is associated with lower remission rate with escitalopram but not with other antidepressants. Neuropharmacology. 2012;38:S314–S446. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang L, et al. p11 is up-regulated in the forebrain of stressed rats by glucocorticoid acting via two specific glucocorticoid response elements in the p11 promoter. Neuroscience. 2008;153:1126–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eriksson TM, et al. Bidirectional regulation of emotional memory by 5-HT1B receptors involves hippocampal p11. Mol. Psychiatry. 2012 doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.130. Advance online publication, October 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egeland M, Warner-Schmidt J, Greengard P, Svenningsson P. Neurogenic effects of fluoxetine are attenuated in p11 (S100A10) knockout mice. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;67:1048–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Réty S, et al. The crystal structure of a complex of p11 with the annexin II N-terminal peptide. Nature Struct Biol. 1999;6:89–95. doi: 10.1038/4965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerke V, Creutz CE, Moss SE. Annexins: Linking Ca2+ signalling to membrane dynamics. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:449–461. doi: 10.1038/nrm1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerfen CR, Surmeier DJ. Modulation of striatal projection systems by dopamine. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:441–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Neill MF, Conway MW. Role of 5-HT(1A) and 5-HT(1B) receptors in the mediation of behavior in the forced swim test in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:391–398. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lucas G, et al. Serotonin(4) receptor agonists are putative antidepressants with a rapid onset of action. Neuron. 2007;55:712–725. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svenningsson P, et al. Biochemical and behavioral evidence for antidepressant-like effects of 5-HT6 receptor stimulation. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4201–4209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3110-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Debauve G, Capouillez A, Belayew A, Saussez S. The helicase-like transcription factor and its implication in cancer progression. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:591–604. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7392-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaidi SK, et al. Nuclear microenvironments in biological control and cancer. Nature Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:454–463. doi: 10.1038/nrc2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J, et al. Nuclear annexin II negatively regulates growth of LNCaP cells and substitution of ser 11 and 25 to glu prevents nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of annexin II. BMC Biochem. 2003;4:10–25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vishwanatha JK, Jindal HK, Davis RG. The role of primer recognition proteins in DNA replication: association with nuclear matrix in Hela cells. J. Cell. Science. 1992;101:25–34. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barlow CA, Laishram RS, Anderson RA. Nuclear phosphoinositides: a signaling enigma wrapped in a compartmental conundrum. Trends Cell. Biol. 2010;20:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hargreaves DC, Crabtree GR. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling: genetics, genomics and mechanisms. Cell Res. 2011;21:396–420. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheridan PL, Schorpp M, Voz ML, Jones KA. Cloning of an Snf2/Swi2-Related Protein That Binds Specifically to the Sph Motifs of the Sv40 Enhancer and to the Hiv-1 Promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:4575–4587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1965;124:319–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.901240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eriksson PS, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nature Med. 1998;4:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Malberg JE, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:9104–9110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santarelli L, et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science. 2003;301:805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1083328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holtzheimer PE, Mayberg HS. Deep brain stimulation for psychiatric disorders. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;34:289–307. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanacora G, Zarate CA, Krystal JH, Manji HK. Targeting the glutamatergic system to develop novel, improved therapeutics for mood disorders. Nature Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:426–437. doi: 10.1038/nrd2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tzang RF, et al. Association study of p11 gene with major depressive disorder, suicidal behaviors and treatment response. Neurosci Lett. 2008;447:92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perlis RH, et al. Pharmacogenetic analysis of genes implicated in rodent models of antidepressant response: association of TREK1 and treatment resistance in the STAR(*)D study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2810–2819. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ripke S, et al. A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:497–511. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]