Media depictions of tanned individuals as healthy and attractive help to establish sociocultural beliefs about appearance,1,2 and popular television programs glamorize indoor tanning.3 Our understanding of media influences in the persistence of tanning behavior may be informed by examining how media influences relate to disordered eating, which, like tanning, can be viewed as an attempt to exert control over one’s physical appearance. According to objectification theory,4 cultural and media-driven sexual objectification of women, including the portrayal of an ideal feminine body image (eg, thin, toned, bronzed appearance), can socialize women to internalize these ideals and begin to view themselves as objects to be looked at and evaluated. Women may critically compare themselves to these ideal images and find themselves wanting. Feelings of shame often emerge when women realize they do not look like the feminine ideal. These feelings motivate young women to engage in appearance control behaviors in an attempt to look more like the ideal. To our knowledge, this research will be the first to test if the body objectification framework can be applied to indoor tanning.

Methods

Participants were 155 female undergraduate students recruited from an introductory course at a large northeastern university. Participants were given course credit, and the study was approved by the Pennsylvania State University institutional review board.

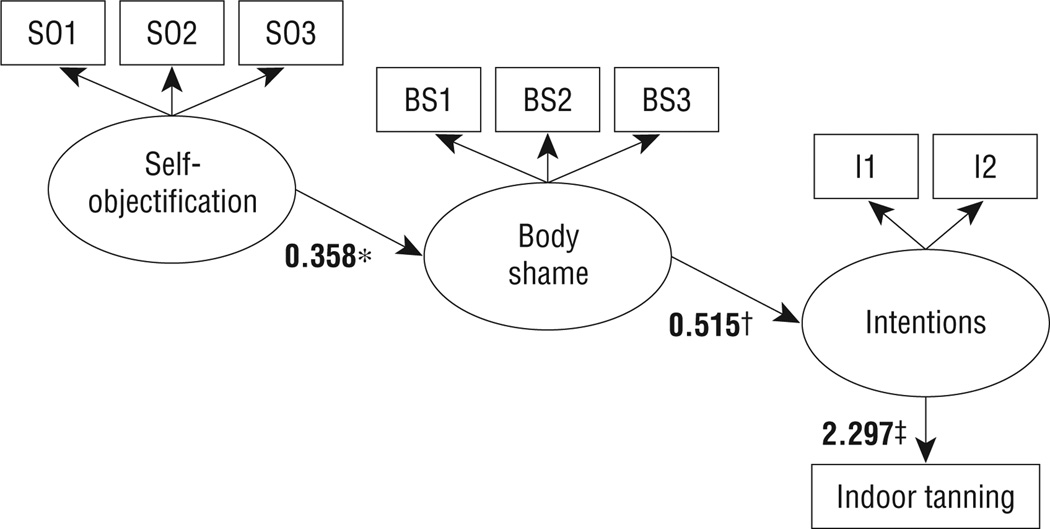

We used a structural equation model to test the relationship between body objectification constructs and indoor tanning (Figure). The objectified body consciousness scale5 was used to measure self-objectification (ie, viewing one’s body as an object to be looked at and evaluated) and body shame.

Figure 1.

Conceptual structural equation model. Boldface numbers represent regression weights. All factor loadings were significant (P < .001), and all residual covariances were significant (P < .001). Item residual variances and factor residual variances are not depicted in the model. BS indicates body shame; I, intention; SO, self-objectification. *P < .05; †P < .01; ‡P < .001.

Self-objectification (Figure, SO1, SO2, and SO3) was measured by rating each of 3 statements on a 7-point Likert-type response scale: (1) “I rarely compare how I look with how other people look” (reverse coded); (2) “During the day, I think about how I look many times”; and (3) “I rarely worry about how I look to other people” (reverse coded) (α = .70). Body shame (Figure, BS1, BS2, and BS3) was also assessed by rating 3 statements: (1) “I feel like I must be a bad person when I don’t look as good as I could”; (2) “Even when I can’t control my weight, I think I’m an okay person”; and (3) “When I’m not exercising enough, I question whether I am good” (α = .73). Intentions to engage in indoor tanning (Figure, I1 and I2) were measured by rating the answers to each of 2 questions on a 7-point scale: (1) “Do you intend to indoor tan in the next year?”; (2) “Do you intend to indoor tan more than 10 times in the next year?” The number of past year indoor tanning sessions was measured with an open-ended response item.

Results

Fit indices used to assess model fit indicated a good model fit: ; P = .13; root mean square error of approximation, 0.046; and comparative fit index, 0.986. The self-objectification latent variable was significantly related to body shame (Figure) (β = 0.358; P < .05). Body shame was significantly related to intentions to indoor tan (β = 0.515; P < .01), which were related to past year indoor tanning (β = 2.297; P < .001).

Comment

Our results suggest that the central tenets of body objectification theory can help elucidate motives for indoor tanning behavior among college women. In the present study, viewing one’s body critically was related to body shame. Body shame, hypothesized to lead to appearance control behaviors, was related to intentions to indoor tan and, ultimately, to indoor tanning behavior. With 1 notable exception,2 most published articles on skin cancer interventions do not address the way the media can influence young women’s attitudes about their bodies. Skin cancer intervention messages that address resisting media pressures and increasing body satisfaction and self-esteem, which have some efficacy in disordered eating interventions,6 may produce reductions in deliberate tanning.

In the present study, the use of a convenience sample and the cross-sectional nature of the data are limitations. However, the extensive literature on body objectification provides support for the hypothesized associations.7 Future research would benefit from detailed measurement of media exposure to determine outlets that have the most influence on self-objectification and, ultimately, indoor tanning behavior. Future work should examine how these variables are related to other predictors of tanning. These preliminary findings suggest that cultural and media-driven body objectification might motivate young women to engage in indoor tanning behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported in part by grant RSGPB- 05- 011- 01 CPPB from the American Cancer Society (Drs Turrisi).

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Stapleton and Robinson. Acquisition of data: Stapleton. Analysis and interpretation of data: Stapleton, Turrisi, and Todaro. Drafting of the manuscript: Stapleton and Todaro. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Stapleton, Turrisi, and Robinson. Statistical analysis: Stapleton and Turrisi. Study supervision: Robinson.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: Dr Robinson is editor of Archives of Dermatology but was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to accept this work for publication.

References

- 1.Cafri G, Thompson JK, Jacobsen PB. Appearance reasons for tanning mediate the relationship between media influences and UV exposure and sun protection. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(8):1067–1069. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.8.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson KM, Aiken LS. Evaluation of a multicomponent appearance-based sun protective intervention for young women: uncovering the mechanisms of program efficacy. Health Psychol. 2006;25(1):34–46. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poorsattar SP, Hornung RL. Television turning more teens toward tanning? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):171–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fredrickson BL, Roberts TA. Objectification theory: toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychol Women Q. 1997;21:173–206. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKinley NM, Hyde JS. The objectified body consciousness scale: development and validation. Psychol Women Q. 1996;20:181–215. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stice E, Shaw H. Eating disorder prevention programs: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(2):206–227. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moradi B, Huang YP. Objectification theory and psychology of women: a decade of advances and future directions. Psychol Women Q. 2008;32:377–398. [Google Scholar]