Abstract

Introduction

Cystic Fibrosis pulmonary disease is characterized by intermittent episodes of acute lung symptoms known as “pulmonary exacerbations”. While exacerbations are classically treated with parenteral antimicrobials, oral antibiotics are often used in “mild” cases.

Objectives

We determined how often management progressed to IV therapy. We also examined multiple courses of oral antimicrobials within one exacerbation and identified patient factors associated with unsuccessful treatment.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart audit of oral antibiotic use in CF patients from March 2009 through March 2010, for “mild” CF exacerbations.

Results

Administration of a single versus multiple courses of oral antibiotics for treatment of “mild” CF exacerbation avoided progression to IV therapy 79.8% and 50.0% of the time, respectively. Overall, oral antibiotics circumvented the need for IV therapy 73.8% of the time. Using multi-variant analysis, we found multiple patient characteristics to be independent risk factors for oral antibiotic failure including a history of Pseudomonas infection (OR 2.13, CI 1.29 – 3.54), Cystic Fibrosis Related Diabetes (OR 1.85, CI 1.00 – 3.41), Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (OR 3.81, CI 1.38 – 10.56), low socioeconomic status (OR 1.67, CI 1.04 – 2.67), and calculated Baseline FEV1 < 75% of predicted prior to an acute exacerbation (OR 1.93, CI 1.20 – 3.08). Decline in FEV1 > 10%, weight for age, body mass index, distance from the CF center, and gender were not significant.

Conclusion

Our observations suggest that one course of oral antimicrobials is frequently effective in outpatient CF pulmonary exacerbations but exacerbations requiring more than one course of oral antibiotics are likely to require IV therapy.

Keywords: Cystic Fibrosis, exacerbation, antibiotics, pneumonia

INTRODUCTION

Cystic Fibrosis lung disease is characterized by inspissated mucus colonized by bacteria, resulting in chronic infection and recurrent acute “flare ups” of these lung infections, known as pulmonary exacerbations. Though variable in severity, pulmonary exacerbations are characterized by a constellation of symptoms and findings that include increased cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, weight loss, change in mucus production, fatigue, hemoptysis, and often a decline in lung function testing (1). While contributing to progressive lung damage (2, 3), these exacerbations also inflict economic and social pressures on patients and their families through both the acute illness and its treatment (4). Parenteral antibiotic therapy and hospitalization is considered the “gold” standard of pulmonary exacerbation management (5, 6). This results in missed work and/or school, medication and equipment costs, and risk of exposure to health-care associated pathogens.

Oral antibiotics are often prescribed for “mild” pulmonary exacerbations to circumvent the need for parenteral therapy and inpatient treatment. Although this practice appears common among CF centers, a literature search reveals no well-established practice guidelines defining when a pulmonary exacerbation merits a trial of oral therapy (6, 7). A recent “State of the Art” paper presented a table of agents and susceptible pathogens, however, these recommendations were not studied in a clinical trial (8). Moreover, a Cochrane review suggests a need for research in the area (9). Unfortunately, what constitutes a “mild” exacerbation versus severe has no well-established definition (1). Unlike IV antibiotics, oral antibiotics are very well accepted by CF patients (10). Oral therapy can avoid hospitalization, cost less, and may be less disruptive to the patient’s life. However, recent CF clinical practice guidelines suggest that the intensive supportive care during hospitalization may be preferred to home parenteral treatment (11). Indeed, one caveat of outpatient therapy is the inability to monitor adherence with medications, increased airway clearance, and nutritional supplementation. Nonetheless, our experience suggests that most patients treated with oral antibiotics for “mild” pulmonary exacerbations demonstrate resolution of symptoms. However, when symptoms persist or progress despite oral antimicrobial therapy, parenteral treatment is necessary. In these cases, oral antibiotic outpatient treatment may represent a delay in exacerbation treatment, which has been associated with loss of lung function (12).

The primary objective of this study was to identify the overall success rate of oral antimicrobials used to treat symptoms of CF pulmonary exacerbations at our center, which covers the entire state of Oregon and southern Washington state. We also hypothesized that patients who fail to improve after one course of oral therapy are unlikely to improve on subsequent courses. Finally, we hypothesized that many patient factors previously associated with poor CF outcomes would also be associated with oral antimicrobial treatment failure.

ETHICS

The study received the approval of the OHSU Institutional Review Board (IRB), IRB00006430, for protection of human subjects and protected health information. The IRB determined that informed consent was not required.

METHODS

We identified the medical records of potential subjects by using the CF Foundation patient registry, which contains 257 OHSU patients in approximately a 2:1 ratio of pediatric to adult patients (our pediatric center follows until age 21 years). We then identified and retrospectively audited the medical records of CF patients who initiated oral antibiotic treatment for a pulmonary exacerbation at OHSU from March 2009 to March 2010. Included patients were evaluated in person and treated to resolution by our CF center for a pulmonary exacerbation at least once during the study period. Included pulmonary exacerbations were defined as attending physician supervised encounters during which a CF pulmonary exacerbation was diagnosed and treated outpatient with an oral antimicrobial directed against a sensitive pathogen based on the most recent surveillance culture and sensitivities. Patients without sensitivities to oral agents (e.g. quinolone resistant pseudomonas) were not offered oral therapy. Diagnosis of pulmonary exacerbation was made by the attending physician. Clinical severity scoring was not employed at the time of encounters. At the OHSU CF center, assessment and management of pulmonary exacerbations is consistent between pediatric and adult providers as all providers meet weekly to discuss patient encounters and treatment.

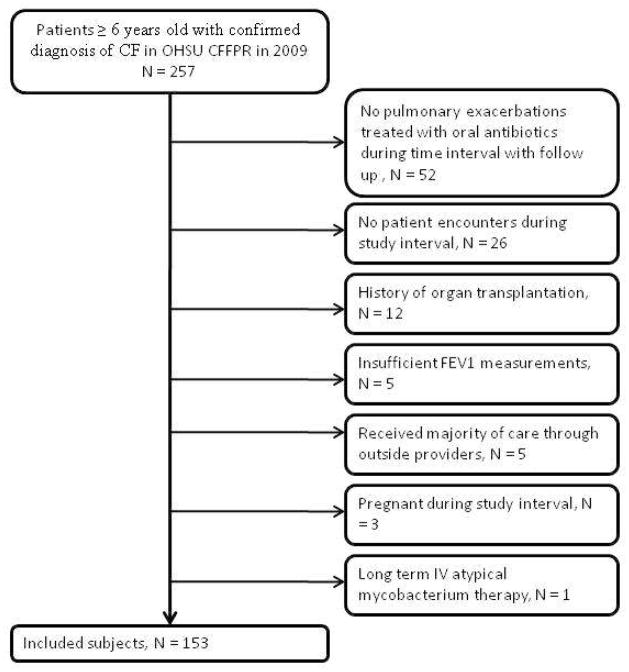

Encounters were excluded if follow-up was incomplete or if there was a history of organ transplantation, pregnancy during the study interval, long term IV atypical mycobacterium therapy, inability to perform pulmonary function testing (including all patients less than 6 years of age), and/or receipt of the majority of care outside of OHSU (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient Selection

Initial patient exacerbation encounters triaged to admission and/or IV therapy were not included. Patients receiving chronic suppressive inhaled anti-pseudomonal antibiotics or anti-inflammatory therapy with oral azithromycin were included in our analysis but data regarding these therapies was not included. Patients receiving non-standardized aerosolized anti-staphylococcal regimens were excluded (e.g. inhaled vancomycin).

We analyzed the records of OHSU clinic, phone and emergency department encounters pertaining to CF pulmonary exacerbations for which oral antibiotics were prescribed as initial treatment. As the only CF center in the state of Oregon (98,386 sq miles, population 3,825,657), geography dictates that telephone initiated encounters are common at our center. Phone-initiated encounters were only considered, however, if the patient was evaluated in person during the course of the exacerbation.

We recorded demographics including gender, age, insurance status, and whether patient home distance is greater than 100 miles from the CF center. Medicaid insurance and lack of health insurance were used as surrogates for low socioeconomic status (SES) (13). We also recorded concomitant medical history including Cystic Fibrosis Related Diabetes (CFRD) and Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA). We recorded patient BMI (for patients ≥18 years old), weight percentile for age (for patients <18 years old), FEV1 absolute (Liters), and FEV1 percent predicted. A “baseline” FEV1 was calculated as the mean of all non-sick values (explicitly documented to be at their baseline health) recorded for twelve months prior to the day of the exacerbation visit. This calculated value was then used to calculate the percent change in FEV1 during exacerbations. Respiratory surveillance culture results were noted for every exacerbation when collected. History of at least one Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and/or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa) growth during the two years prior to each exacerbation was considered a positive history for this analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of Patients and Exacerbations

| Descriptor | Patients | Exacerbations | Average number of exacerbations per pt |

|---|---|---|---|

| total number | 153 | 365 | 2.4 |

| female | 86 | 209 | 2.4 |

| male | 67 | 156 | 2.3 |

| peds < 21years | 108 | 252 | 2.3 |

| adults >=21years | 49* | 113 | 2.3 |

| average baseline FEV1 (% predicted) | 78.97 | 78.21 | |

| average weight percentile (<21) | 39.26 (recorded in 51 patients on first exacerbation of year) | 37.29 (recorded in 98 exacerbations) | |

| average BMI (>=21 y/o) | 19.41 (recorded in 76 patients on first exacerbation of the year) | 19.76 (recorded in 159 exacerbations) | |

| home greater than 100 miles | 34 | 69 | 2 |

| medicaid or no insurance | 60 | 140 | 2.3 |

| ABPA | 7 | 24 | 3.4 |

| CFRD | 21 | 53 | 2.5 |

| # Hx of Pa | 92 | 217 | 2.4 |

| # Hx of MRSA | 34 | 82 | 2.4 |

some patients turned 21 during the study period so 108 +49 does not equal 153

CF patients may have multiple exacerbations in a year. New exacerbations were differentiated from previous exacerbations if there was 1) a resolution of symptoms and/or 2) a return of PFTs to baseline in between exacerbations. In cases, there was no timely clinical documentation of treated exacerbation outcome. In these instances, we defined exacerbation duration as the length of the prescribed antibiotic course plus 14 days of no new symptoms or complaints (28 days) in the medical record or clinic telephone log. Exacerbations were excluded when there was no further patient contact within 6 months of treatment initiation (n=12).

Using these timelines, oral antibiotic treatment failure was defined as any physician-diagnosed CF pulmonary exacerbation initially treated with one or more courses of oral antibiotics without resolution of symptoms or evidence of clinical improvement, which was then treated with IV antibiotics.

We defined oral antibiotic treatment success as pulmonary exacerbations treated with oral antibiotics that were never treated with parenteral antibiotic therapy. In both cases we noted the number of oral antibiotic courses and the duration of each antimicrobial treatment, as determined by the providers at the time of the exacerbation.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

In order to increase statistical power, CF pulmonary exacerbations were evaluated as the independent variable of interest (n=365), rather than each patient. This fit with our study’s objective of identifying the characteristics of an exacerbation that are likely to affect treatment decisions and outcomes, such as the decline in FEV1 from baseline during a particular exacerbation. We analyzed all exacerbation characteristics as they were upon presentation when the initial treatment decision was made (or within five days of treatment initiation if the patient was first prescribed antibiotics over the phone).

A logistic model was initially applied for univariate analysis of each exacerbation variable to determine the estimated odds ratio of failing oral antimicrobial therapy. Next, the logistic model was applied for bi-variate and multivariate analysis of pre-selected clinically important characteristic combinations. In all cases, a 95% confidence interval non-inclusive of 1 (or a p-value of <0.5) was considered significant.

RESULTS

Of the 365 unique pulmonary exacerbations in the 153 patients included in our analysis, the overall resolution rate was 73.4% with the administration of oral antimicrobials alone. Exacerbations treated with only one course of oral antibiotics had a 79.8% success rate whereas exacerbations that were treated with more than one course of antibiotics only resolved 50.0% of the time. A single course of oral antibiotics averaged 13.4 days (median 14 days) while IV antibiotics, when required, were administered for an average of 14.45 days (median 19 days). All non-responders were offered IV therapy. Patients included in our study group had an average of 2.4 physician-diagnosed CF pulmonary exacerbations per year that were treated with oral antibiotics.

We found five exacerbation characteristics expressed at initial presentation to be significantly associated with oral antibiotic failure: a history of Pa infection on surveillance culture (OR 2.13, CI 1.29 – 3.54), a history of CFRD (OR 1.85, CI 1.00 – 3.41), a history of APBA (OR 3.81, CI 1.38 – 10.56), low SES (OR 1.67, CI 1.04 – 2.67), calculated Baseline FEV1 < 75% of predicted prior to acute exacerbation (OR 1.93, CI 1.20 – 3.08) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistically significant risk factors for oral antibiotic failure:

| Exacerbation characteristic | Estimated odds ratio | 95% CIs | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Hx of Pa | 2.13 | 1.29 – 3.54 | 0.0033 |

| CFRD | 1.85 | 1.00 – 3.41 | 0.049 |

| ABPA | 3.81 | 1.38 – 10.56 | 0.0099 |

| Low SES | 1.67 | 1.04 – 2.67 | 0.033 |

| Baseline FEV1% predicted < 75% | 1.923 | 1.20 – 3.08 | 0.0064 |

While not statistically significant, female gender and low weight status in children (weight percentile <50%) trended towards significance (p = 0.075 and 0.084, respectively). We noted that patient age, history of MRSA colonization, and home distance >100 miles from the CF center were not significantly associated with oral antibiotic failure in our analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Non-significant patient factors associated with oral antibiotic failure for CF pulmonary exacerbation.

| Exacerbation characteristic | Estimated odds ratio | 95% CIs | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Hx of MRSA | 1.39 | 0.81 – 2.37 | 0.23 |

| Patient gender (female) | 1.55 | 0.40 – 1.05 | 0.075 |

| Home > 100 miles from OHSU | 1.03 | 0.57 – 1.87 | 0.93 |

| Pancreatic sufficiency | 0.54 | 0.15 – 1.90 | 0.34 |

| Drop in FEV1% predicted > 10% | 1.18 | 0.70 – 1.99 | 0.53 |

| Patient age <21, Weight %ile <50% | 2.4 | 0.89 – 6.47 | 0.084 |

| Patient age ≥ 21, BMI < 20 | 1.77 | 0.68 – 4.60 | 0.25 |

| 6 ≤Age<12 vs Age≥18 | 1.48 | 0.83 – 2.65 | 0.19 |

| 12≤Age<18 vs Age≥18 | 1.07 | 0.62 – 1.85 | 0.62 |

| 12≤Age<18 vs 6≤Age<12 | 0.72 | 0.39 – 1.35 | 0.62 |

| Age≥18 vs 6≤Age<12 | 0.67 | 0.38 – 1.20 | 0.34 |

Bi- and multivariate analysis essentially revealed the same significant patient characteristics as noted above with no co-morbidities (Table 4). We also showed that exacerbations, which did not respond to a first course of oral antibiotics, were more likely to require IV therapy for resolution. There was an odds ratio of 3.95 of oral antibiotic treatment failure if the exacerbation was treated with more than one course of oral antibiotics (p <0.0001).

Table 4.

Bi- and multivariate analysis of patient characteristics associated with oral antibiotic treatment failure.

| Exacerbation characteristic | Estimated odds ratio | 95% CIs | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Baseline FEV1% predicted < 75% + | 2.00 | 1.24 – 3.21 | 0.0043 |

| Low SES | 1.75 | 1.08 – 2.82 | 0.022 |

|

| |||

| Baseline FEV1% predicted < 75% + | 1.99 | 1.23 – 3.20 | 0.0049 |

| Low SES + | 1.83 | 1.13 – 2.97 | 0.015 |

| Female | 1.61 | 0.98 – 2.63 | 0.059 |

|

| |||

| Low SES + | 1.74 | 1.08 – 2.80 | 0.023 |

| Female | 1.62 | 1.00 – 2.64 | 0.052 |

|

| |||

| Hx of Pa + | 2.11 | 1.27 – 3.50 | 0.004 |

| Low SES | 1.64 | 1.02 – 2.64 | 0.043 |

|

| |||

| CFRD + | 1.85 | 1.00 – 3.43 | 0.05 |

| Low SES | 1.67 | 1.04 – 2.68 | 0.034 |

|

| |||

| ABPA + | 4.06 | 1.45 – 11.35 | 0.0075 |

| Low SES | 1.73 | 1.07 – 2.78 | 0.025 |

|

| |||

| Time since the last exacerbation + | 1.00 | 0.99 – 1.00 | 0.0045 |

| Baseline FEV1% predicted < 75% | 1.80 | 1.11 – 1.06 | 0.017 |

|

| |||

| Low SES + | 1.70 | 2.73 – 2.93 | 0.029 |

| Home > 100 miles from OHSU | 0.91 | 0.50 – 1.66 | 0.75 |

|

| |||

| Drop in FEV1% predicted > 10% + | 1.14 | 0.67 – 1.94 | 0.63 |

| Baseline FEV1% predicted < 75% | 1.91 | 1.20 – 3.06 | 0.0069 |

|

| |||

| Hx of MRSA + | 1.36 | 0.79 – 2.34 | 0.26 |

| Female gender | 1.53 | 0.95 – 2.48 | 0.082 |

|

| |||

| CFRD + | 1.67 | 0.89 – 3.13 | 0.11 |

| Female gender | 1.43 | 0.87 – 2.34 | 0.16 |

|

| |||

| Hx of MRSA + | 1.34 | 0.78 – 2.30 | 0.3 |

| CFRD | 1.81 | 0.98 – 3.34 | 0.06 |

|

| |||

| BMI <20 + | 1.92 | 0.72 – 5.17 | 0.19 |

| CFRD | 2.89 | 1.19 – 7.04 | 0.019 |

|

| |||

| BMI <20 + | 1.71 | 0.65 – 4.50 | 0.28 |

| Baseline FEV1% predicted < 75% + | 2.02 | 0.66 – 6.14 | 0.22 |

| Low SES | 1.73 | 0.67 – 4.45 | 0.26 |

|

| |||

| W-ile <50% + | 2.52 | 0.92 – 6.92 | 0.072 |

| Baseline FEV1% predicted < 75% + | 2.39 | 1.28 – 4.44 | 0.0061 |

| Low SES | 1.66 | 0.93 – 2.97 | 0.086 |

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that in our single center CF practice of mixed urban and rural populations, approximately three of four “mild” CF exacerbations treated oral antimicrobials will resolve without progressing to IV therapy. To our knowledge, there is no other published literature looking at generalized oral antimicrobial use for “mild” exacerbations. There are studies, however, that have investigated the failure rates of specific oral antibiotics in the presence of specific CF pathogens. In 1986 and ‘87, Scully et al. examined the efficacy of Ciprofloxacin in treating various Pa infections, finding an 80–82% clinical success rate in CF pulmonary exacerbation (14, 15). Richard et al. demonstrated a 93% success rate among CF patients with Pa who received a single 14-day course of Ciprofloxacin for an exacerbation (16). The increased efficacy noted in this study may be explained by hospitalization for oral antibiotic therapy and the exclusion of patients with advanced disease. CF specific studies examining the oral treatment of other prevalent CF pathogens are scarce. A 14 year Scandinavian study revealed a 74% success rate in the eradication of S. aureus from the sputum of CF patients treated with an oral regimen, but clinical symptoms were not an outcome measure in the study (17). Oral treatment of H. influenza was explored by two studies that suggested a 70–73% eradication rate and a 100% clinical response rate (18, 19). These studies, including our own, support the notion that oral antibiotics are frequently effective in resolving acute exacerbation symptoms when oral therapy is deemed appropriate.

Unfortunately, the retrospective nature of our analysis and some practitioner documentation practices precludes the categorization of specific symptoms or findings associated with an individual exacerbation. At our center, signs and symptoms of CF pulmonary exacerbation include increased cough, chest pain, change in mucus production, fatigue, “streaky” hemoptysis, change in lung examination, and/or a decline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). Furthermore, our providers agree that shortness of breath, hypoxia, significant concomitant weight loss, frank hemoptysis, would likely exclude patients from consideration of home based oral therapy. A recent review of CF exacerbation management points out the need for a definition of mild versus severe exacerbation as important in defining therapeutic goals (1) as there are currently no definitions. Using clinical scoring systems to standardize clinical assessment and therapeutic management has been associated with improved lung function(7), but did not define a specific degree of severity.

There are multiple descriptions in the literature of markers for poor outcomes in CF (3, 12, 13, 20–23). These are generally markers of more severe disease, and, as such, were not surprisingly associated with failure of oral antibiotics in our analysis. The strongest association that we noted was with a recent history of active ABPA. The prevalence of ABPA in CF centers was recently estimated around 7.8% (24), however, this is higher than our center’s prevalence of 4.6%. Thus, ABPA as marker of predicting oral antibiotic failure may be greater than we were able to show. Explanations for this association might include symptom overlap between ABPA and CF exacerbation, which renders it difficult to distinguish an ABPA flare from a pulmonary exacerbation.

CFRD has been reported to increase morbidity and mortality in CF through pulmonary complications, and is likely a marker of more advanced CF disease. In our study, CFRD diagnosis was associated with nearly double the odds of failing oral antibiotics. The prevalence of CFRD in our study population is lower than predicted by the literature, which suggests that further study is warranted to better understand its true effect.

Our study further confirms previous reports that low SES is associated with poor outcomes in CF (13). This risk factor is especially important at OHSU where almost 40% of our patients are on government issued Medicaid or without medical insurance. By using Medicaid status as a proxy for low SES, Schechter et al found that the percent predicted FEV1 for patients receiving Medicaid was 9.1% less than that for non-Medicaid patients. In addition, while access to specialty care was similar to insured counterparts, their study showed that patients with low SES also had an increased risk of death. In Oregon, Medicaid patients are provided outpatient medication without co-pay and prescriptions are frequently dispensed at our center. Nonetheless, our data confirms the observation that other access-independent, socioeconomic-related factors are at play.

Severity of lung disease is also a known risk factor in CF exacerbation response with baseline FEV1 percent predicted commonly used as a validated marker of disease severity (25–27). In our study, having a calculated baseline FEV1 less than 75% of predicted was associated with almost twice the risk of failing oral therapy. Reason suggests that “sicker” patients may have increased bacterial resistance as well as more limited ability to cough and effectively clear bacteria-dense mucus from the distal airways. Prior oral antibiotic literature confirms the notion that “sicker” patients do worse (14, 28). In a prospective trial of oral fluoroquinolone for Pseudomonas infection in CF, for example, patients with FEV1 <60% did not respond as well as those with FEV1 >80% (28).

Species of bacterial colonization is a known factor affecting the rate of pulmonary decline in CF, in particular Pa. CF exacerbations are often not due to acquisition of new strains of bacteria but rather to clonal expansion of previously colonizing strains (1). Orally delivered agents may not obtain levels in the sputum required for killing these dense bacterial colonies and synergistic agents like aminoglycosides are simply not available in oral preparations. Given increasing evidence that MRSA is a concern in CF (20, 22, 23), it was surprising that MRSA did not prove to be significant in our analysis. This may be explained by our center’s lower than average MRSA rate (16.2%). Because of our small sample size, we did not detect a significant difference in response by antimicrobial agent prescribed (data not shown). We chose not to further analyze other specific organisms, however, S. aureus, H. influenzae, S. maltophilia, and Achromobacter xylosoxidans were also seen in culture results.

Female gender, while not significant in our relatively small study population, would have likely emerged as a significant co-factor for oral antibiotic failure in a larger powered analysis. Female patients with CF may have more body image concerns and are less likely to maintain nutrition, which is a known modifier of CF lung health (29, 30).

It was also surprising to find that sizable decline in FEV1 was not associated with treatment failure since one might assume that a large drop in FEV1 portends a more severe exacerbation and thus a worse outcome. There are at least two explanations for this observation. First, with our limited population size, only a small number of patients treated with oral therapy experienced a drop in FEV1% predicted > 10%. Second, clinician judgment alone determined severity of the exacerbation and treatment plan. We detected a bias to treat large declines in FEV1 with IV therapy and hospitalization immediately, especially among patients with more severe baseline lung function (data not shown). Thus, when analyzing this association in univariate analysis the results were likely skewed by those patients with normal lung function (FEV1 % predicted >100%) who were more likely to be treated successfully with oral antibiotics despite large declines in FEV1.

Our observations and analysis has several key limitations. First and foremost, as a retrospective review, our results must be interpreted with caution. There was no standard clinical score or severity assessment used. Second, our study population was limited to primarily pediatric-aged patients with mild underlying disease and hence our results cannot be applied across all CF patients. Third, our selection bias for patients with bacterial cultures sensitive to oral agents selected for a less chronically infected cohort and limited the total number of adult patients. We also did not control for use of concurrent anti-pseudomonal aerosolized antibiotics and variable airway clearance therapeutics but rather assumed that all patients were receiving the baseline standard of care. Finally, our sample size was too small to determine if progression to IV therapy resulted in loss of lung function.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that oral antimicrobials are a useful in outpatient management of “mild” acute CF exacerbation when deemed appropriate by the provider. However, our analysis also reveals that known markers of CF severity are associated with increased oral treatment failure. We also determined that treatment with multiple courses of oral antibiotics is less likely to avert progression to parenteral therapy when the initial course is unsuccessful. Thus, our study supports the practice of escalating therapy (IV, hospital) in patients who fail to improve in a timely manner with a single trial of oral therapy for exacerbation in order to maximize treatment benefit and minimize the possibly deleterious effects of delaying optimal treatment (12). Given a non-trivial rate of oral antibiotic failure in our analysis, further prospective study is needed to determine if oral antibiotic failure is associated with worse patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

E.C.B. - Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

K.D.M. - NICHD K12HD057588 and Parker B Francis Fellowship

The authors gratefully acknowledge Drs. William Skach and Michael Powers for their insightful review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Roles: ECB participated in all aspects of the project, TN designed performed the analysis, MCW participated in study design, analysis, and manuscript review, KDM participated in all aspects of the project.

NO conflicts to report

References

- 1.Goss CH, Burns JL. Exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. 1: Epidemiology and pathogenesis. Thorax. 2007 Apr;62(4):360–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.060889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.FitzSimmons SC. The changing epidemiology of cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1993 Jan;122(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanders DB, Bittner RC, Rosenfeld M, Redding GJ, Goss CH. Pulmonary exacerbations are associated with subsequent FEV(1) decline in both adults and children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. Oct 21; doi: 10.1002/ppul.21374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Britto MT, Kotagal UR, Hornung RW, Atherton HD, Tsevat J, Wilmott RW. Impact of recent pulmonary exacerbations on quality of life in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2002 Jan;121(1):64–72. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsey BW. Management of pulmonary disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1996 Jul 18;335(3):179–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607183350307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson RLBJ, Ramsey BW. Pathophysiology and management of pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(8):918–51. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-505SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kraynack NC, McBride JT. Improving care at cystic fibrosis centers through quality improvement. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 Oct;30(5):547–58. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1238913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson RL, Burns JL, Ramsey BW. Pathophysiology and Management of Pulmonary Infections in Cystic Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Oct 15;168(8):918–51. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-505SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remmington T, Jahnke N, Harkensee C. Oral anti-pseudomonal antibiotics for cystic fibrosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD005405. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005405.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodson ME, Roberts CM, Butland RJ, Smith MJ, Batten JC. Oral ciprofloxacin compared with conventional intravenous treatment for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in adults with cystic fibrosis. Lancet. 1987 Jan 31;1(8527):235–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flume PA, Mogayzel PJ, Jr, Robinson KA, Goss CH, Rosenblatt RL, Kuhn RJ, et al. Cystic Fibrosis Pulmonary Guidelines: Treatment of Pulmonary Exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 Nov 1;180(9):802–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200812-1845PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanders D, Bittner RCL, Rosenfield Margaret, et al. Failure to Recover to Baseline Pulmonary Function after Cystic Fibrosis Pulmonary Exacerbation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2010;182:627–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1421OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schechter MS, Shelton BJ, Margolis PA, Fitzsimmons SC. The association of socioeconomic status with outcomes in cystic fibrosis patients in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 May;163(6):1331–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.9912100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scully BE, Neu HC, Parry MF, Mandell W. Oral ciprofloxacin therapy of infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Lancet. 1986 Apr 12;1(8485):819–22. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90937-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scully BE, Nakatomi M, Ores C, Davidson S, Neu HC. Ciprofloxacin therapy in cystic fibrosis. Am J Med. 1987 Apr 27;82(4A):196–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richard DA, Nousia-Arvanitakis S, Sollich V, Hampel BJ, Sommerauer B, Schaad UB. Oral ciprofloxacin vs. intravenous ceftazidime plus tobramycin in pediatric cystic fibrosis patients: comparison of antipseudomonas efficacy and assessment of safety with ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging. Cystic Fibrosis Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997 Jun;16(6):572–8. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199706000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szaff M, Hoiby N. Antibiotic treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infection in cystic fibrosis. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1982 Sep;71(5):821–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1982.tb09526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pressler T, Szaff M, Hoiby N. Antibiotic treatment of Haemophilus influenzae and Haemophilus parainfluenzae infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1984 Jul;73(4):541–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1984.tb09968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rayner RJ, Hiller EJ, Ispahani P, Baker M. Haemophilus infection in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 1990 Mar;65(3):255–8. doi: 10.1136/adc.65.3.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Block JK, Vandemheen KL, Tullis E, Fergusson D, Doucette S, Haase D, et al. Predictors of pulmonary exacerbations in patients with cystic fibrosis infected with multi-resistant bacteria. Thorax. 2006 Nov;61(11):969–74. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.061366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders D, Hoffman L, et al. Return of FEV(1) after pulmonary exacerbation in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45:127–34. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dasenbrook EC, Checkley W, Merlo CA, Konstan MW, Lechtzin N, Boyle MP. Association between respiratory tract methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and survival in cystic fibrosis. JAMA. Jun 16;303(23):2386–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dasenbrook EC, Merlo CA, Diener-West M, Lechtzin N, Boyle MP. Persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and rate of FEV1 decline in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008 Oct 15;178(8):814–21. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-327OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agarwal R. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Chest. 2009 Mar;135(3):805–26. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mekus F, Laabs U, Veeze H, Tummler B. Genes in the vicinity of CFTR modulate the cystic fibrosis phenotype in highly concordant or discordant F508del homozygous sib pairs. Hum Genet. 2003 Jan;112(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00439-002-0839-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drumm ML, Konstan MW, Schluchter MD, Handler A, Pace R, Zou F, et al. Genetic modifiers of lung disease in cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2005 Oct 6;353(14):1443–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schluchter MD, Konstan MW, Drumm ML, Yankaskas JR, Knowles MR. Classifying severity of cystic fibrosis lung disease using longitudinal pulmonary function data. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 Oct 1;174(7):780–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200512-1919OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen T, Pedersen SS, Hoiby N, Koch C. Efficacy of oral fluoroquinolones versus conventional intravenous antipseudomonal chemotherapy in treatment of cystic fibrosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1987 Dec;6(6):618–22. doi: 10.1007/BF02013055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma R, Florea VG, Bolger AP, Doehner W, Florea ND, Coats AJ, et al. Wasting as an independent predictor of mortality in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2001 Oct;56(10):746–50. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.10.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson ML, Jacobs DR, Jr, Milla CE. Longitudinal changes in growth parameters are correlated with changes in pulmonary function in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 2003 Sep;112(3 Pt 1):588–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]