Abstract

The breakdown and release of hyaluronan (HA) from the extracellular matrix has been hypothesized to act as an endogenous signal of injury. To test this hypothesis, we generated mice that conditionally overexpressed human hyaluronidase 1 (HYAL1). Mice expressing HYAL1 in skin either during early development or by inducible transient expression exhibited extensive HA degradation, yet displayed no evidence of spontaneous inflammation. Further, HYAL1 expression activated migration and promoted loss of DCs from the skin. We subsequently determined that induction of HYAL1 expression prior to topical antigen application resulted in a lack of an antigenic response due to the depletion of DCs from the skin. In contrast, induction of HYAL1 expression concurrent with antigen exposure accelerated allergic sensitization. Administration of HA tetrasaccharides, before or simultaneously with antigen application, recapitulated phenotypes observed in HYAL1-expressing animals, suggesting that the generation of small HA fragments, rather than the loss of large HA molecules, promotes DC migration and subsequent modification of allergic responses. Furthermore, mice lacking TLR4 did not exhibit HA-associated phenotypes, indicating that TLR4 mediates these responses. This study provides direct evidence that HA breakdown controls the capacity of the skin to present antigen. These events may influence DC function in injury or disease and have potential to be exploited therapeutically for modification of allergic responses.

Introduction

The early inflammatory response to tissue injury has been proposed to involve recognition of components of damaged cells by pattern recognition receptors, such as TLRs (1). These dead cell components have been called damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) (2) and include intracellular molecules, such as the chromatin-associated protein high-mobility group box 1 (3), heat shock proteins (4), and purine metabolites, such as ATP (5), uric acid (6), DNA (7, 8), and RNA (9, 10) in addition to molecules released by extracellular matrix degradation, such as heparan sulfate (11), biglycan (12, 13), versican (14), and hyaluronan (HA) (15, 16). Currently, several lines of experimental evidence support the important role of pattern recognition receptors in vitro and in vivo. However, interpretation of the unique function of specific DAMPs has been difficult due to the multiple microbial products that exist in a wound and the potential for small amounts of microbial products to be present in reagents used to study these responses.

HA has been of interest as a DAMP because it is particularly abundant in skin (17). It is a major component of the dermal and epidermal extracellular matrix and is synthesized at the cell surface as a long, linear nonsulfated glycosaminoglycan composed of repeating units of the disaccharides (-D-glucuronic acid β1-3-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine β1-4-) (18). The nascent size of HA is typically very large, with mass >300 kDa. An extraordinarily wide variety of biological functions have been attributed to HA, including roles as a space-filling molecule maintaining hydration, lubrication of joints, and actions in angiogenesis (19), cancer (20), and immune regulation (21, 22).

Large-molecular-weight HA undergoes breakdown into small fragments after injury. These HA fragments can then interact with endothelial cells, macrophages, and DCs, a process thought to be mediated by TLR4 and/or TLR2 (23, 24). The size of HA after breakdown influences its function. Small, tetrasaccharide, and hexasaccharide fragments of HA have been shown to influence DCs in culture via TLR4 (25, 26), while larger, 135-kDa fragments have been shown to initiate alloimmunity (27). However, a clear understanding of the physiological functions of HA has been brought into question by the potential for microbial contamination that could also activate TLRs and the complexity of injury models that initiate several other immunological events coincident with HA catabolism.

Herein, we sought to specifically investigate the function of HA breakdown in vivo by using a mouse genetic approach to overexpress hyaluronidase 1 (HYAL1), thus producing HA fragments without inflicting injury or altering the microbial milieu. This approach, combined with directly comparing the response to purified HA tetrasaccharides, demonstrates in vivo that HA breakdown is a initiator of DC migration from the skin and effects the capacity to sensitize with a topical antigen. Our unexpected findings redefine the current models of the physiological functions of HA and suggest this process may moderate allergic sensitization under conditions of acute or chronic injury.

Results

Generation of HYAL1-overexpressing mice.

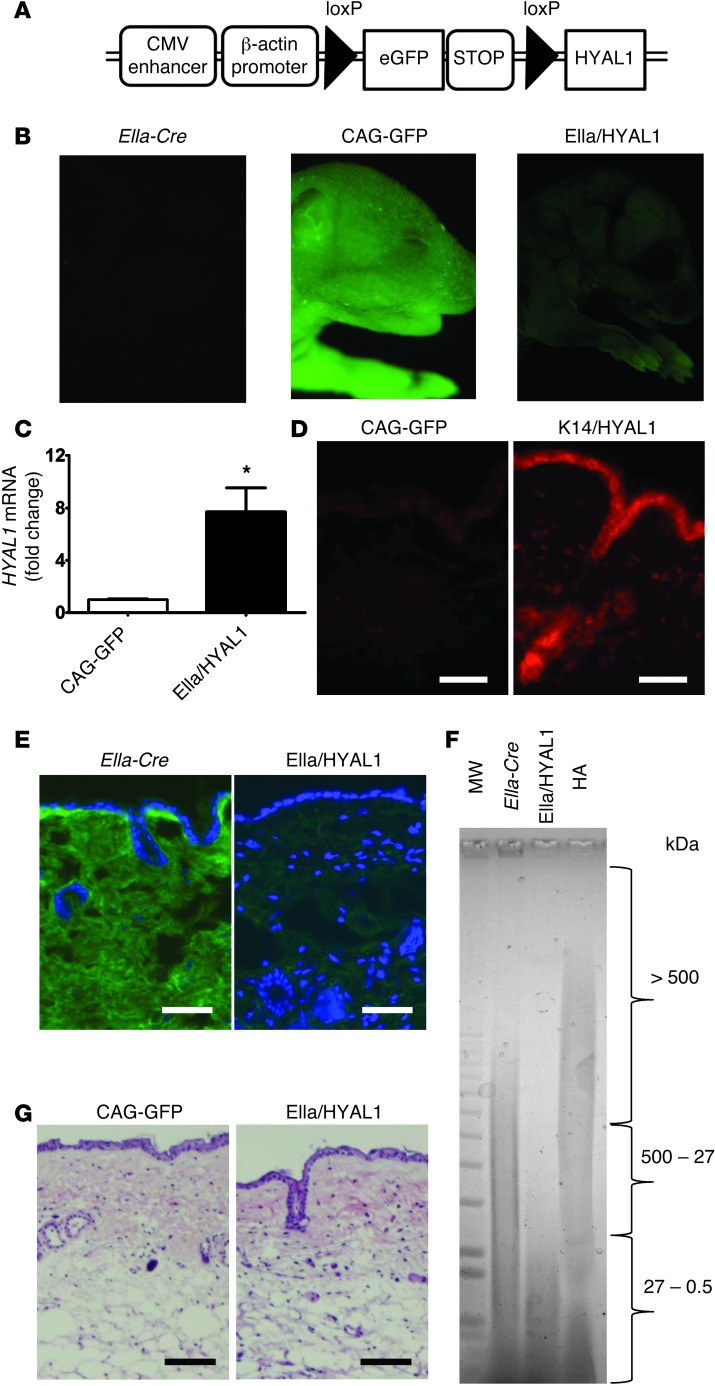

To study the role of HA breakdown in vivo, we engineered transgenic mice for conditional expression of human hyaluronidase 1 (HYAL1), termed CAG-GFPfloxed-HYAL1 Tg mice (CAG-GFP mice) (Figure 1A; for details of the vector construction see Supplemental Figure 1 and Supplemental Methods; supplemental material available online with this article; doi: 10.1172/JCI67947DS1). Breeding with EIIa-Cre mice was done for systemic expression during early development (EIIa/HYAL1 mice), breeding with KRT14-Cre mice (K14/HYAL1 mice) was done for constitutive conditional overexpression in the basal epidermis, and inducible epidermal expression was done by tamoxifen application to CAG-GFPfloxed-HYAL1 Tg mice crossed with KRT14-CreERT mice (K14CreERT/HYAL1 mice). As expected, decreased EGFP fluorescence was observed in EIIa/HYAL1 mice systemically expressing Cre (Figure 1B), indicating that the reporter gene and stop codon had been excised. The specificity of K14 promoter was confirmed by the loss of GFP in the epidermis (Supplemental Figure 2). Expression of the target gene was also confirmed by quantifying the abundance of human HYAL1 mRNA by qPCR (Figure 1C). Protein expression of HYAL1 in K14/HYAL1 mice was confirmed by immunostaining (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Generation of HYAL1-overexpressing mice.

(A) Schematic for conditional overexpression of HYAL1. Filled triangles represent loxP sites. (B) Fluorescence images of transgenic mouse pups (approximately 2 days old) expressing GFP (CAG-GFPfloxed-HYAL1 Tg mice: CAG-GFP and EIIa/HYAL1 mice) and EIIa-Cre mice. (C) Quantitative PCR demonstrating HYAL1 overexpression in normal skin from EIIa/HYAL1 mice and control (CAG-GFP) mice (*P < 0.05; n = 6). (D) Frozen sections of skin from HYAL1-overexpressing (K14/HYAL1) and control (CAG-GFP) mice were stained with an antibody recognizing HYAL1 (red). Scale bar: 100 μm; n = 5 per group. (E) HA immunostaining. Frozen sections of skin from EIIa/HYAL1 mice and control EIIa-Cre mice were stained with HABP and FITC-streptoavidin (green) and DAPI for nuclei (blue). Scale bar: 100 μm; n = 5 per group. (F) The size distribution of HA extracted from skin, as analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. A similar total amount of HA was loaded in each lane, as determined by carbazole assay. Gel was stained with Stains-All. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lane 2, HA extracted from the skin of control EIIa-Cre mice; lane 3, HA extracted from skin of HYAL1-expressing (EIIa/HYAL1) mice shows decrease in average detectable size to <27 kDa; lane 4, human umbilical cord HA as standard. (G) Skin of control (CAG-GFP) mice and HYAL1-overexpressing (EIIa/HYAL1) mice stained with H&E. Scale bar: 100 μm. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results.

The function of HYAL1 to degrade HA was confirmed by observing a loss of staining for large-molecular-weight HA in the skin using an HA binding protein that binds large HA (Figure 1E). Furthermore, analysis of the size of HA extracted from the skin of HYAL1-overexpressing mice confirmed this observation by showing loss of detectable large-molecular-weight HA above 27 kDa and a subsequent increase in abundance of smaller HA between 27 and 0.5 kDa (Figure 1F). Small-molecular-weight HA correspond in size to HA oligosaccharides from small tetrasaccharides to linear HA fragments containing approximately 68 disaccharide units.

There was no evidence of spontaneous inflammation and no other apparent histological changes in the skin of mice constitutively overexpressing HYAL1 (Figure 1G). Previous reports have identified CXC chemokine release, such as macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (Mip-2), as a rapid and sensitive indicator of a response to HA in vitro (16, 24). Constitutive embryonic hyaluronidase expression induced no difference in Mip-2 protein in the skin (Supplemental Figure 3). Additionally, we measured a panel of 24 other cytokines and chemokines in skin of K14/HYAL1 and K14CreERT/HYAL1 mice by Luminex and observed that there was no difference when compared with the controls (Supplemental Figure 4, A and B). There were also no significant differences in Il10 mRNA expression in the skin or LNs after HYAL1 expression (Supplemental Figure 5). Furthermore, no systemic morphologic abnormalities were detected by 12 weeks of age in the EIIa/HYAL1 group compared to control groups after an anatomical and histological survey of the brains, hearts, circulatory systems, lungs, gastrointestinal tracts, genitourinary tracts, hematopoietic systems, or endocrine tissues (data not shown). No laboratory abnormalities were detected by hematologic survey, including complete blood count, blood chemistry, coagulation, and the bleeding time, except for the slight but significant increase in LDL of EIIa/HYAL1 mouse serum (P = 0.011) (Supplemental Table 1). Thus, in contrast to prior measurements of the response to HA fragments in vitro, the degradation of HA in vivo did not initiate an apparent inflammatory response.

HYAL1 expression or HA tetrasaccharides induce loss of DCs from the skin.

We next examined the number of MHC class II–positive DCs in the epidermis of constitutive HYAL1-overexpressing mice. Analysis by flow cytometry demonstrated a significant decrease in the number of MHC class II and CD11c double-positive cells in K14/HYAL1 mouse epidermis (Figure 2, A and B). The reduced numbers of MHC class II–positive cells in K14/HYAL1 mouse epidermis were confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Figure 2C). These results indicated that the number of Langerhans cells in the K14/HYAL1 mouse epidermis was decreased.

Figure 2. Decreased DC number in the epidermis and dermis of HYAL1-overexpressing mice.

(A) Representative dot plots of MHC class II and CD11c double-positive viable DCs from epidermal sheets of transgenic mice (control, CAG-GFP mice). Numbers within plots denote the percentage of cells within the respective gates. IA/IE, MHC class II. (B) Percentage of MHC class II+CD11c+ DCs in epidermal sheets of mice by flow cytometry (***P < 0.001; n = 3). (C) Immunohistochemistry of MHC class II in epidermal sheets. Scale bar: 50 μm; n = 6. (D) Dermal single cell suspensions of K14/HYAL1 mice and control (K14-Cre) mice were subjected to flow cytometry analysis, and MHC class II– and CD11c-positive cell numbers were assessed (*P < 0.05; n = 3). Mean ± SEM. (E) Number of langerin-positive cells among MHC class II– and CD11c-positive cells (*P < 0.05; n = 3). Mean ± SEM. (F) Flow cytometry analysis of dermal single cell suspensions showing expression of CD11b and CD103 from K14/HYAL1 and control (K14-Cre) mice. Cells were gated on langerin+, MHC class II+, and CD11c+ cells. (G) Cells gated on langerin-negative, MHC class II+, and CD11c+ cells showing expression of CD11b and CD103. Numbers represent the percentage of the cells in the indicated gate. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Similar to the response seen in the epidermis, the total number of MHC class II+ and CD11c+ double-positive dermal DCs was significantly decreased in the dermis of HYAL1-overexpressing K14/HYAL1 mice (Figure 2D). Furthermore, the total numbers of langerin+, MHC class II+, and CD11c+ dermal DCs were also significantly lower in HYAL1-overexpressing mice compared with those in control mice (Figure 2E). In particular, HYAL1 overexpression resulted in decreased numbers of langerin+ MHC class II+/CD11c+/CD103–/CD11b+ DCs in the dermis (Figure 2F). However, there was no difference in the frequency of langerin–, MHC class II+, and CD11c+ cells expressing CD103 and CD11b in the dermis (Figure 2G).

To examine the dynamic nature of epidermal and dermal DC response to expression of HYAL1, we next evaluated the skin in the tamoxifen-inducible K14-dependent Cre system (28). HYAL1 mRNA increased significantly in the skin 48 hours after tamoxifen application (Supplemental Figure 6). The number of the MHC class II+ cells in K14CreERT/HYAL1 mouse epidermis was identical to that in controls before tamoxifen application, but, coincident with the timing of HYAL1 expression, DCs started to decrease 48 hours after tamoxifen treatment (Figure 3, A and B). There was no evidence of DC apoptosis after HYAL1 expression, as detected by the expression of active caspase-3 (data not shown). However, the loss of DCs was accompanied by the expression of CD80, a marker of DC maturation (29) (Figure 3C). To determine whether the loss of DCs from the skin was due to accelerated migration, we evaluated the effect of HYAL1 on the migration of DCs to regional LNs. HYAL1 expression was induced by topical application of tamoxifen for 2 days, which was then painted on the same site with the hapten eFluor670 and examined inguinal draining LNs (DLNs) 24 hours later. The presence of CD11c+eFluor670+ cells was examined in inguinal DLNs. The number of CD11c+eFluor670+ DCs in DLNs of HYAL1-overexpressing mice significantly increased compared with that in control mice treated with the tamoxifen vehicle (acetone/DMSO) and eFluor670 (Figure 3, D and E). Furthermore, the frequency of total CD11c+ cells in the inguinal LNs was significantly increased after tamoxifen-dependent HYAL1 overexpression (Figure 3, F and G). Thus, the loss of DCs from the skin and coincident increase of DCs in the regional LNs support the conclusion that HYAL1 expression enhanced the migration of DCs from the skin. This conclusion was also supported by the direct demonstration of increased cells in the LN that were labeled with eFluor670 and an increase of the DC maturation marker CD80 that is associated with increased migration (29).

Figure 3. Decreased DC number in the epidermis of K14CreERT/HYAL1 mice after tamoxifen application.

(A) DCs per mm2 were determined by counting MHC class II immunostained cells in 8 different microscopic fields of the epidermal sheets 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours after topical tamoxifen application. Mean and SEM are shown on the graph (n = 4). (B) 0, 24, 48, 72 hours after tamoxifen treatment, epidermal sheets were harvested and stained with MHC class II antibody. Scale bar: 50 μm. (C) 48 hours after tamoxifen treatment, epidermal sheets were stained with CD80 antibody. Scale bar: 50 μm. (D) Increased trafficking of skin DCs in tamoxifen-dependent HYAL1-overexpressing transgenic mice. Representative plots of eFluor670 fluorescence plotted against CD11c from DLNs of transgenic mice 24 hours after painting eFluor670 dissolved in acetone on shaved and tamoxifen- or vehicle-treated abdominal skin. (E) Number of CD11c+eFluor670+ DCs in DLNs of tamoxifen-dependent HYAL1-overexpressing mice (K14CreERT/HYAL1, black bar) compared with vehicle-treated control mice (K14CreERT/HYAL1, gray bar) (n = 4). (F) Representative dot plots of CD11c against side scatter from DLNs of transgenic mice 72 hours after tamoxifen or vehicle treatment on abdominal skin. (G) Percentage of CD11c+ DCs in DLNs of tamoxifen-dependent HYAL1-overexpressing mice (K14CreERT/HYAL1, black bar) compared with vehicle-treated control mice (K14CreERT/HYAL1, gray bar) (n = 4). Mean and SEM are shown on the graph. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments with similar results. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

To distinguish between effects on DCs coming from the generation of HA fragments or the loss of large-molecular-weight HA and further confirm the capacity of HA to affect DC function, we injected purified low-molecular-weight HA tetrasaccharides (oligoHA) into wild-type mouse skin. Injection of oligoHA recapitulated all of the responses seen after HYAL1 overexpression. The number of MHC class II–positive cells in the epidermis significantly decreased at the site of oligoHA injection in a time-dependent manner (Figure 4A). This decrease in MHC class II–positive DCs coincided with an increase in CD80+ cells (Figure 4, B and C). Finally, the frequency of CD11c cells that were labeled on the skin surface with FITC increased in DLNs of oligoHA-injected mice compared with that in PBS-injected control mice (Figure 4D). Taken together, these data further support the conclusion that the production of HA fragments by HYAL1 initiates DC maturation and migration out of the skin.

Figure 4. OligoHA induces DC emigration and maturation.

(A) DCs per mm2 were determined by counting MHC class II immunostained cells in 8 different microscopic fields of the epidermal sheets 0, 2, 4, 8, and 24 hours after oligoHA (400 μg) or PBS injection of C57BL/6 WT mice. (B) Frequency of CD80+ cells in MHC class II+ cells in the epidermal sheets after injection. (C) Two hours after injection, epidermal sheets were harvested and stained with MHC class II or CD80 monoclonal antibody. Scale bar: 50 μm. (D) Increased DCs in DLNs after oligoHA injection (400 μg). Representative dot plots of FITC fluorescence plotted against CD11c from DLNs of C57BL/6 WT mice 24 hours after painting FITC dissolved in acetone on shaved abdominal skin. Data are representative of 2 or 3 separate experiments with similar results. Mean and SEM are shown on the graphs (n = 4). ***P < 0.001.

HYAL1 expression and HA tetrasaccharides influence allergic sensitization.

To determine the physiological significance of the effects of HA digestion, we next studied its role in the development of contact hypersensitivity (CHS), a function attributed in part to langerin+ dermal DCs (30, 31). Consistent with the depletion of DCs in their skin, mice that constitutively express HYAL1 in the epidermis (K14/HYAL1 mice) had a large decrease in the CHS response to the topical application of the powerful antigenic hapten DNFB (Figure 5, A and B). Mice expressing HYAL1 systemically (EIIa/HYAL1 mice) showed a similar decreased CHS response (Supplemental Figure 7, A and B). These mice also demonstrated a significantly reduced capacity to deliver eFluor670 hapten to the DNLs when compared with that of control mice (Figure 5, C and D and Supplemental Figure 8). However, no difference in the abundance of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells was detected in the thymus and LNs (data not shown) and no evidence for a change in skin barrier function of HYAL1-overexpressing mice (EIIa/HYAL1 mice) was seen, as evaluated by transepidermal water loss measurements (data not shown). These data show that the depletion of DCs by constitutive HYAL1 expression is functionally important, resulting in greatly decreased CHS response. Of note, the normal endogenous expression of mouse Hyal1 did not influence CHS response under these conditions, as no difference was observed when Hyal1–/– mice were compared to controls (Supplemental Figure 9)

Figure 5. Constitutive overexpression of HYAL1 in the skin suppresses CHS.

(A) Restoration of the CHS response in HYAL1-overexpressing (K14/HYAL1, black bar) mice compared with control (CAG-GFP, gray bar) mice. The data represent the increase in ear thickness for groups of 6 mice. (B) Representative histopathology of the ears of K14/HYAL1 mice and control mice elicited with vehicle or DNFB. Scale bar: 200 μm. (C) Defective trafficking of skin DCs in HYAL1-overexpressing transgenic mice. Representative dot plots of eFluor670 fluorescence plotted against CD11c in viable cells from DLNs of transgenic mice 24 hours after painting eFluor670 dissolved in 1:1 acetone/dibutylphthalate on shaved abdominal skin. (D) Number of CD11c+eFluor670+ DCs in DLNs of transgenic mice (n = 3). (E) LN cells from sensitized CAG-GFP mice were adoptively transferred by i.v. injection into K14/HYAL1 and CAG-GFP mice. Ear elicitation with DNFB and measurement of ear thickness were performed for groups of 4 mice. (F) LN cells from sensitized K14/HYAL1 and CAG-GFP mice were adoptively transferred by i.v. injection into CAG-GFP mice. Ear elicitation with DNFB and measurement of ear thickness were performed for groups of 4 mice. (G) CHS response in C57BL/6 WT mice injected subcutaneously with oligoHA (black bar) or PBS (gray bar) in the dorsal skin 72 hours before sensitization with DNFB (n = 5). Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Next, to determine whether the lack of CHS influenced by HYAL1 expression was due to decreased sensitization phase or abnormal elicitation phase, we examined this response after adoptive LN transfer. Transfer of DLN cells from control mice sensitized with DNFB to HYAL1-overexpressing mice restored the CHS response, despite the expression of HYAL1 during elicitation (Figure 5E and Supplemental Figure 10A). In contrast, transfer of DLN cells from donor DNFB-sensitized HYAL1-overexpressing mice to control WT mice did not result in an inflammatory response to DNFB (Figure 5F and Supplemental Figure 10B). These data support the conclusion that the decreased DC number inhibited CHS through diminished capacity to sensitize against the allergen.

Since the administration of HA tetrasaccharides was shown to also deplete DCs from the skin (Figure 4), we next examined whether this would also deplete the CHS response. A significant decrease in CHS was observed when oligoHA were injected at the site 3 days before sensitization (Figure 5G). The topical application of oligoHA in an oil-in-water emulsion cream base also led to CHS suppression if administered 3 days before sensitization (data not shown). Furthermore, local, conditional induction of HYAL1 expression had a similar effect if done before DNFB exposure. When tamoxifen was applied to K14CreERT/HYAL1 mice 7 days before application of DNFB, the CHS response was significantly suppressed (Supplemental Figure 11). These findings showed that when expression of HYAL1, or application of HA oligos, took place before antigen exposure, then the preceding loss of DCs resulted in an inability to initiate allergic sensitization.

In contrast to the design of the experiments shown in Figure 5, we next designed an approach to induce HYAL1 just before and during sensitization but before depletion of DCs from the skin. Under these conditions, we hypothesized that the activation of DC migration might accelerate the rate of allergic sensitization. K14CreERT/HYAL1 mice were treated with tamoxifen immediately before sensitization of the same site with DNFB. Tamoxifen-treated K14CreERT/HYAL1 mice had a greatly increased CHS response if elicitation was measured only 1.5 days after sensitization (Figure 6, A and B), a time when control mice had not yet developed the capacity to respond to the antigen. If elicitation was tested 5 days after sensitization, control mice demonstrated the expected CHS response, although HYAL1-expressing mice continued to show a slightly enhanced elicitation reaction (Supplemental Figure 12). Injection of oligoHA during sensitization also recapitulated the acceleration effect (Figure 6, C and D). These observations are consistent with findings that HYAL1 overexpression stimulates DC migration from the skin and show that this effect can speed the time it takes to effectively induce allergic sensitization.

Figure 6. Tamoxifen-dependent overexpression of HYAL1 or injection of HA tetrasaccharides accelerates sensitization of CHS.

(A and B) CHS response after early elicitation (1.5 days after sensitization) in tamoxifen-dependent HYAL1-overexpressing mice (K14CreERT/HYAL1, black bar) compared with acetone/DMSO-treated control mice (K14CreERT/HYAL1, gray bar). The data represent the increase in ear thickness for groups of 4 mice. (C and D) CHS response after early elicitation (1.5 days after sensitization) in mice injected with oligoHA (400 μg, black bar) or PBS (gray bar) subcutaneously at the same time and site of sensitization. The results represent the increase in the ear thickness of groups of 5 mice. Mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Function of HYAL1 or HA tetrasaccharides is dependent on TLR4.

To determine the mechanism by which HYAL1 expression induced skin DC maturation and modulated CHS sensitization, we next evaluated the role of TLR4. Expression of HYAL1 in a Tlr4–/– background prevented mice from responding to HYAL1, since in the absence of TLR4 no decrease in the abundance of epidermal or dermal DC populations was detectable despite breakdown of HA (Figure 7A and Supplemental Figure 13). OligoHA injections also did not alter the migration of cutaneous DCs into DLNs after FITC application in Tlr4–/– mice (Figure 7B). Furthermore, mice were rescued from the suppression of CHS if HYAL1 was constitutively expressed in a Tlr4–/– background (Figure 7C). OligoHA injections also had no effect on either suppression or acceleration of sensitization when they were performed in Tlr4–/– mice (Figure 7, D and E). In contrast, breeding of HYAL1-overexpressing mice to a Cd44–/– background did not rescue them from suppression of CHS (data not shown).

Figure 7. Modification of DC function by HA catabolism is TLR4 dependent.

(A) DCs per mm2 were determined by counting MHC class II immunostained cells in 8 different microscopic fields of the epidermal sheets of K14/HYAL1 (HYAL1), K14-Cre (K14), TLR4-deficient K14/HYAL1, and TLR4-deficient K14-Cre mice (n = 4). (B) Increased DCs in DLNs after injection with oligoHA subcutaneously at the same time as and site of FITC application. Number of CD11c+FITC+ DCs in DLNs of oligoHA-injected C57BL/6 WT mice and TLR4-deficient mice compared with those in PBS-injected control mice 24 hours after painting FITC on shaved abdominal skin was analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 4). (C) Evaluation of CHS in TLR4-deficient HYAL1-overexpressing mice. The black bar and the dark gray bar represent TLR4-deficient K14/HYAL1 and control mice (K14-Cre), respectively. The data represent the increase in ear thickness for groups of 5 mice. (D) CHS response in C57BL/6 WT mice and TLR4-deficient mice injected subcutaneously with oligoHA or PBS in the dorsal skin 72 hours before sensitization with DNFB (n = 5). (E) Increase in ear thickness after early elicitation with DNFB (1.5 days after sensitization). C57BL/6 WT mice and TLR4-deficient mice were injected subcutaneously with oligoHA or PBS at the same time and site of sensitization (n = 5). Mean and SEM are shown on the graph. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate that the action of hyaluronidase, or an increase of small fragments of HA, activates cutaneous DCs and modulates the capacity to induce contact allergy. These observations directly show an important physiologic role for HA breakdown. Our model system shows for the first time to our knowledge that HA fragments modify the cutaneous immune response in the absence of the many other variables present following an injury or infection and confirms the dependence upon TLR4. Somewhat surprisingly, despite the action though TLR4, we did not observe inflammatory responses typically attributed to TLR4. Thus, these findings provide new insights into how DAMPs, and in particular HA, can influence immunity.

HA is one of many substances that have been proposed to act as a DAMP in injured tissues (16, 24, 26, 32, 33). However, prior publications supporting this hypothesis have relied on experiments that were subject to the criticism that undetected microbial contamination and/or other secondary influences may affect the results (16, 24). To avoid this limitation, we generated mice in which we could control expression of HYAL1 in a conditional manner, thus fragmenting HA in the extracellular matrix without injury. Somewhat surprisingly, the anatomy, skin structure, morphology, permeability, growth, and baseline inflammation were unaffected by embryonic expression of HYAL1 and extensive constitutive degradation of HA. This genetic strategy permitted the observation that HA breakdown appears to selectively alter the function of DCs in the skin.

Hyaluronidases hydrolyze the hexosaminidic β1-4 linkages between N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and D-glucuronic acid residues in HA, digesting the large polymer into fragments. In humans, there are 6 members of the hyaluronidase family: HYAL1, hyaluronidase 2–4, PH-20, and HYALP1. HYALP1 is the major mammalian hyaluronidase in somatic tissues, acting to degrade large-molecular-weight HA to small tetrasaccharides (34). The enzyme is lysosomal and exhibits highest activities at acidic pH but is still weakly active up to pH 5.9 (34, 35). Reitinger et al. reported that HYAL1 variant degraded HA more efficiently up to pH 5.9 (35). However, HYAL1 is also present in human serum (34) and urine (36) and can act at neutral pH. The importance of HYAL1 clinically is seen in mucopolysaccharidosis type IX, in which mutations in the HYAL1 gene are associated with accumulation of HA, short stature, and multiple periarticular soft tissue masses (37). We found that deletion of Hyal1 in the mouse did not alter the CHS response, suggesting this enzyme is not essential for DC function, at least under conditions lacking injury. Even during injury, several other mechanisms could contribute to HA breakdown. Therefore, it is not clear from the current work in which compartment transgenic HYAL1 was active or if endogenous Hyal1 is essential for control of DC function. Future work will seek to define the mechanisms by which HA is digested under conditions of injury and also identify the specific sizes of native HA oligosaccharides that are active under these conditions.

The findings shown here provide new insight into mechanisms that regulate the CHS response, a process subject to continuing debate but responsible for significant human clinical morbidity through allergic exposures at home and in the workplace (38). In support of our observations, prior studies have shown that the magnitude of the CHS reaction is associated with the total number of skin DCs, in addition to the presence or absence of a particular skin DC population (39). In our constitutive HYAL1-overexpressing system, HA degradation led to decreased total numbers of DCs in both the epidermis and dermis. Interestingly, this effect was also seen when we studied K14/HYAL1 mice, in which HYAL1 presumably digested HA only in the epidermis. We hypothesize that the effect on dermal DCs with the K14 epidermal driver was due to the ability of the low-molecular-weight HA produced in the epidermis to enter the dermis and affect the dermal DC pool. This conclusion is consistent with the ability of subcutaneously injected oligoHA to affect dermal DCs. Moreover, the timing of the appearance of HA fragments was critical to the phenotype observed. Early activation of DCs by HA degradation or administration of HA oligos inhibited the capacity to sensitize by enhancing migration, thus leading to the eventual depletion of DCs in the skin. In contrast, simultaneous DC activation and antigen exposure accelerated the time required to elicit an inflammatory response.

A loss of HA from either the extracellular matrix or the DC surface could theoretically alter the CHS response by other mechanisms. For example, DCs express CD44, a major HA binding receptor (40), and this could influence trafficking. However, we showed the ability to rescue the loss of DCs by crossing HYAL1-expressing mice into Tlr4–/– mice, but this was not seen when crossed into Cd44–/– mice. We also showed the loss of DCs after injection of HA tetrasaccharides. Neither observation could occur if the mechanism of inhibition of CHS was dependent only on loss of large-molecular-weight HA. The inhibition of sensitization also appeared not to be due to activation of suppression. The level of Il10 mRNA in the skin and LN tissues of K14/HYAL1 mice did not differ from that in the tissues of control K14-Cre mice, although aberrant IL-10 expression can result in deletion of DCs in chronic viral infections (41). There was also no change in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells after HYAL1 expression. Another possible contrary explanation was that constant exposure of transgenic mouse skin to HA was actually proinflammatory, and the chronic inflammatory stimulation might then either induce apoptosis or lead to a cytokine milieu that indirectly induced DC maturation. However, the absence of any observable increase in apoptosis or in inflammatory cytokines invalidates this alternative scenario. Furthermore, observations of rapid acceleration of sensitization made when oligoHA were applied acutely, or during the response to tamoxifen-induced HYAL1, are not consistent with apoptosis or the need to first induce intermediary stimuli. We believe the major effect on CHS was due to the capacity of small HA fragments to induce maturation of DCs, as seen by activation of CD80, enhanced migration, and subsequent loss of these sentinel cells. This conclusion is consistent with the previous reports that oligosaccharides of HA effectively induce maturation in vitro in DCs via TLR4 (25, 26, 42). In addition, although our observations were made exclusively with HA tetrasaccharides, it is likely that other sizes of HA oligosaccharides were generated by HYAL1 expression and are normally present during injury. Therefore, the possibility that other sizes of HA oligosaccharides may have similar or additional immunological effects remains to be determined.

Actions dependent on TLR4 must address the potential role of LPS, the best known ligand for this pattern recognition receptor. LPS is known to upregulate the expression of antigen-presenting and costimulatory molecules (43). However, LPS contamination cannot be evoked to explain the response to genetic HYAL1 expression, and it is highly unlikely that this molecule contributed to observations made with oligoHA. The endotoxin contamination of tetrasaccharide HA, which we used for the injection, was less than 0.1 EU/ml (0.1 pg/ml) in 1 mg/ml HA. Previous dose-response experiments have shown that LPS contaminations of less than 0.1 ng/ml are unable to promote the DC maturation (42). Although this argument has its limitations, it also emphasizes the power of the transgenic HYAL1 mouse model that does not have the potential for the exogenous microbial contamination.

In conclusion, we show that HA modulates DC function in the skin. Our findings compel a major revision of previous models that predicted that HA breakdown acts mainly to trigger inflammation after injury. In contrast, our findings show that the function of HA fragments is to modify adaptive immune responsiveness to the environment. Such a response is most relevant after wounding and may prevent autoimmunity or excess reaction to injury, phenomenon previously observed in Tlr2–/–Tlr4–/– mice after lung injury (15). These data suggest a new therapeutic approach for altering allergic responses, either accelerating them when they are desirable or inhibiting them when they are unwanted. Fragmentation of HA may also accelerate antigen presentation and development of immune responses to enhance the speed and effectiveness of vaccination. Cutaneous DCs also play a major role in the pathophysiology of several common human skin disorders, including psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Therefore, we believe these findings should promote future studies of the effect of HA catabolism on the modulation of immunity in skin disease.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents.

Endotoxin-free oligoHA (HYA-OLIGO4EF-5) was purchased from Hyalose. HA preparations were free of DNA and protein contamination, as preparations showed no absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm. Human umbilical cord HA and DNFB (2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Biotin-labeled hyaluronic acid binding protein was purchased from Associate of Cape Cod. Antibodies to MHC class II (M5/144.15.2), CD11c (N418), and CD80 (16-10A1) were obtained from eBioscience. Antibodies to CD103 (2E7) and CD11b (M1/70) were obtained from Biolegend. An antibody to CD207/langerin (929F3.01) was obtained from Dendritics. The human HYAL1 antibody (ab85375) was obtained from AbCam. Topical HA fragments were compounded in VANICREAM (Pharmaceutical Specialties). Tamoxifen was purchased from MP Biomedicals.

Animals.

The plasmid for the targeted overexpression of HYAL1 was constructed based on the strategies using the vector pCFE, developed by Ajit Varki (UCSD). Details of the pCFE plasmid can be found in the Supplemental Methods (Supplemental Figure 1A). The essential elements of the pCFE expression construct are the CAG promoter driving the expression of a floxed EGFP gene that is followed by a second gene of interest. This construct is flanked by 2 sets of 1.2-kb chicken β globin insulator regions that act to decrease the influence of local chromatin structure and regulatory elements on the expression construct. The LoxP sites allow Cre-mediated excision of EGFP and its stop codon, enabling the CAG promoter to then drive expression of the downstream target gene in a tissue-specific manner. For assembly of the HYAL1 construct, the full-length human HYAL1 cDNA was amplified from dermal microvascular endothelial cells with forward and reverse primers (5ι-ATAAGATCGCGGCCGCATGGCAGCCCACCTGCTTCCCA and 5ι-GGAGACCCGTTTAAACTCACCACATGCTCTTCCGCTCA). The primers contain Not I and Pme I restriction sites, respectively. The amplified product was subcloned by digestion with Not I and Pme I and inserted into pCFE. The correct sequence and orientation of inserts were verified by enzyme digestion and sequencing. Pvu I– and Sal I–linearized targeting vector DNA was microinjected into the pronucleus of a fertilized ovum (C57BL/6) at the UCSD Transgenic Mouse Core. These microinjected embryos were reimplanted into the oviduct of pseudopregnant female recipients, which gave birth 20 days after implantation. Founders were identified both by PCR and by monitoring EGFP fluorescence. EIIa-Cre (003724), KRT14-Cre (004782), and KRT14-Cre/ERT (005107) transgenic mice and TLR4-deficient mice (007227) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. KRT14-Cre mice were backcrossed for more than 6 generations with C57BL/6J mice in our laboratory for use in subsequent studies. These transgenic mice were crossbred to generate EIIa-Cre or KRT14-Cre/CAG-HYAL1 Tg mice (EIIa/HYAL1 or K14/HYAL1 mice), in which HYAL1 is overexpressed, and littermate controls (CAG-GFP, EIIa-Cre, or K14-Cre mice alone). Offspring were genotyped by PCR using genomic DNA isolated from the tails. All experiments used sex- and age-matched littermates. All animals were housed in barrier conditions, which were approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, in the vivarium of the UCSD School of Medicine. Mice were weaned at 3 weeks, maintained on a 12-hour-light/dark cycle, and fed water and standard rodent chow.

Anatomical and histological analysis.

Tissues embedded in paraffin were sectioned and stained with H&E. Anatomical and histological surveys of organs and tissues, such as brain, heart, and circulatory system, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, hematopoietic system, and the endocrine system of transgenic mice (5 males and 5 females for each group), were examined at the UCSD Murine Histology Core (Nissi M. Varki) for initial screening.

HA staining of mouse skin.

To determine whether HA accumulates in the skin of transgenic mice, these mice were euthanized, and an 8-mm punch biopsy was used to remove a section of full-thickness skin. Skin was embedded in OCT compound and frozen at –20°C. Sections (7-μm thick) were cut, and staining was carried out according to the protocol using biotinylated hyaluronic acid–binding protein and FITC-streptoavidin obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch (44). Fluorescence staining was imaged using an Olympus BX41 fluorescent microscope (Scientific Instrument Company).

GAG release from skin.

Murine skin was homogenized and treated overnight with protease (0.16 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) to degrade protein, followed by purification by anion exchange chromatography using DEAE sephacel (Amersham Biosciences). Columns were washed with a low-salt buffer (0.15 M NaCl in 20 mM sodium acetate; pH 6.0) and eluted with 2 M NaCl. Glycans were desalted by PD10 (GE Healthcare). Uronic acid concentration was determined by carbazole assay (45).

Determination of HA size by agarose gel electrophoresis.

The size distribution of HA was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (46). The HA sample was mixed with TAE buffer containing 2 M sucrose and electrophoresed at 2 V/cm for 10 hours at room temperature. The gel was stained overnight under light-protective cover at room temperature in a solution containing 0.005% Stains-All in 50% ethanol, and destained in water. Hyalose ladders (Hyalose) were used for standards.

Immunization and induction of CHS.

Sex- and age-matched adult transgenic mice (8 to 12 weeks of age) were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, and hair was removed on the dorsal skin by shaving followed by manual depilation. For induction of CHS, the mice were painted with 0.5% DNFB or vehicle (acetone/olive oil, 3:1) on the shaved dorsal skin for sensitization, followed by epicutaneous application of 0.15% DNFB on the dorsum of the ears of the mice on day 5 for elicitation. Ear measurements were done before and 24 and 48 hours after ear challenge using an engineer’s micrometer (Mitutoyo) (47).

Adoptive CHS.

Adoptive CHS was induced as previously described (48). Mice of the various donor strains were sensitized by painting the shaved abdominal skin and both ears with 2% DNFB. Auricular, axillary, maxillary, and superficial inguinal LNs were harvested 5 days later. Single cell suspensions were prepared, and 2 × 107 LN cells were injected i.v. into naive recipient mice. Thickness of both ears of the recipients was measured 24 hours after adoptive cell transfer before painting with 0.15% DNFB, and the swelling was measured 24 hours after painting.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence.

Epidermal sheets were prepared by shaving mouse abdominal skin and then affixing it to slides (epidermis side down) with double-sided adhesive (3M). For the topical induction of Cre recombinase, we applied 200 μl of 4 mg/ml tamoxifen in acetone/DMSO (9:1) once daily on the shaved dorsal skin for 3 days. Slides were incubated in 0.5 M ammonium thiocyanate for 2 hours at 37°C followed by physical removal of the dermis. Tissues were fixed in acetone at 4°C for 10 minutes and blocked with 3% BSA in PBS. Tissues were then stained with an MHC class II or CD80 antibody followed by an anti-rat IgG antibody conjugated with rhodamine (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-hamster IgG antibody conjugated with FITC (eBioscience).

In vivo assay for migration of skin DCs.

The abdominal skin of individual mice was shaved followed by application of 100 μl of 100 μg/ml eFluor670 (65-0840-90, eBioscience) or FITC dissolved in 1:1 acetone/dibutylphthalate (Sigma-Aldrich) or acetone alone. At 24 hours, inguinal LNs were isolated by digestion at 37°C with 0.1% DNase I (MP Biomedicals) and 1 mg/ml collagenase D (Roche). Single cell suspensions were incubated with Fc block (FcgRII/III mAb 2.4G2) for 15 minutes and stained with antibodies to CD11c and MHC class II (49). Stained cells were washed, and the percentage of CD11c+eFluor670+ cells in the DLNs was evaluated by FACS at the VA San Diego Research FACS core facility.

Analysis of epidermal cells.

Preparation of epidermal sheets and single cell suspensions was performed as described previously (32, 50). Briefly, epidermal sheets were incubated in 0.3% Trypsin/GNK solution with 0.1% DNase at 37°C for 20 minutes and filtered. After centrifuging at 500 g for 10 minutes at 4°C, the cell pellet was resuspended and rested for 12 hours in DMEM complete media. Single cell suspensions were stained with antibodies for MHC class II and CD11c, followed by FACS analysis.

Analysis of dermal cells.

Single cell preparations from the dermis were prepared as previously described (51). Briefly, the epidermis was digested with 0.3% trypsin for 120 minutes and removed from the dermis. The dermis was further digested with collagenase XI and hyaluronidase (both from Sigma-Aldrich) for 120 minutes followed by FACS analysis.

Determination of mRNA expression by quantitative RT-PCR.

Real-time PCR was used to determine the mRNA abundance as described previously (52). TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) were used to analyze the expression of HYAL1 and Il10. Gapdh mRNA was used as an internal control. HYAL1 mRNA expression was calculated as relative expression compared to Gapdh mRNA, and all data are presented as normalized data compared to each control (mean of control tissues).

ELISA and Luminex.

Cytokines and chemokines in mouse skin were measured using Luminex Kits (Millipore) according to the manufacture’s instructions. The MIP-2 ELISA Duo Set (R&D Systems) was used to measure mouse Cxcl2/Mip-2 in mouse skin. Normal dorsal skins were isolated with 6-mm punch biopsy from the euthanized mice. The skin sections were placed in a tube with 500 μl 1× radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% SDS, 0.25% deoxycholate, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.4) with protease inhibitor mixture (Complete EDTA-free, Roche) and were beaten with 2.4-mm zirconia beads by a mini-beadbeater apparatus (Biospec Products Inc.) for 50 seconds on full speed. Extracts were then sonicated for 5 minutes in ice-cold water and spun down at 12,000 g for 10 minutes. Supernatant was harvested and kept at –20°C until analysis.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed by using a 2-tailed Student’s t test or 1- or 2-way analysis of variance with Prism software (version 5; GraphPad Software). Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Study approval.

All animal procedures performed in this study were reviewed and approved by the UCSD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The experiments were conducted in accordance with the NIH guidelines for care and use of animals and the recommendations of International Association for the Study of Pain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank N. Varki from UCSD Histology Core Facility for performing mouse necropsies and phenotypic evaluation. We also thank the UCSD Murine Hematology Core for performing mouse blood tests, UCSD Transgenic Mouse Core for generating transgenic mice, and VA San Diego Flow Cytometry Research Core for FACS analysis. This work was supported by NIH grants P01HL057345 and P01HL107150.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Citation for this article: J Clin Invest. 2014;124(3):1309–1319. doi:10.1172/JCI67947.

References

- 1.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(5):373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen GY, Nunez G. Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(12):826–837. doi: 10.1038/nri2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418(6894):191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quintana FJ, Cohen IR. Heat shock proteins as endogenous adjuvants in sterile and septic inflammation. J Immunol. 2005;175(5):2777–2782. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bours MJ, Swennen EL, Di Virgilio F, Cronstein BN, Dagnelie PC. Adenosine 5’-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112(2):358–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kono H, Chen CJ, Ontiveros F, Rock KL. Uric acid promotes an acute inflammatory response to sterile cell death in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(6):1939–1949. doi: 10.1172/JCI40124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imaeda AB, et al. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in mice is dependent on Tlr9 and the Nalp3 inflammasome. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(2):305–314. doi: 10.1172/JCI35958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burckstummer T, et al. An orthogonal proteomic-genomic screen identifies AIM2 as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor for the inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(3):266–272. doi: 10.1038/ni.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavassani KA, et al. TLR3 is an endogenous sensor of tissue necrosis during acute inflammatory events. J Exp Med. 2008;205(11):2609–2621. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kariko K, Ni H, Capodici J, Lamphier M, Weissman D. mRNA is an endogenous ligand for Toll-like receptor 3. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(13):12542–12550. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson GB, Brunn GJ, Kodaira Y, Platt JL. Receptor-mediated monitoring of tissue well-being via detection of soluble heparan sulfate by Toll-like receptor 4. J Immunol. 2002;168(10):5233–5239. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babelova A, et al. Biglycan, a danger signal that activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via toll-like and P2X receptors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(36):24035–24048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.014266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schaefer L, et al. The matrix component biglycan is proinflammatory and signals through Toll-like receptors 4 and 2 in macrophages. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2223–2233. doi: 10.1172/JCI23755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim S, et al. Carcinoma-produced factors activate myeloid cells through TLR2 to stimulate metastasis. Nature. 2009;457(7225):102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature07623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang D, et al. Regulation of lung injury and repair by Toll-like receptors and hyaluronan. Nat Med. 2005;11(11):1173–1179. doi: 10.1038/nm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor KR, Trowbridge JM, Rudisill JA, Termeer CC, Simon JC, Gallo RL. Hyaluronan fragments stimulate endothelial recognition of injury through TLR4. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(17):17079–17084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310859200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tammi R, Ripellino JA, Margolis RU, Tammi M. Localization of epidermal hyaluronic acid using the hyaluronate binding region of cartilage proteoglycan as a specific probe. J Invest Dermatol. 1988;90(3):412–414. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12456530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weissmann B, Meyer K, Sampson P, Linker A. Isolation of oligosaccharides enzymatically produced from hyaluronic acid. J Biol Chem. 1954;208(1):417–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slevin M, et al. Hyaluronan-mediated angiogenesis in vascular disease: uncovering RHAMM and CD44 receptor signaling pathways. Matrix Biol. 2007;26(1):58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2006.08.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toole BP. Hyaluronan: from extracellular glue to pericellular cue. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(7):528–539. doi: 10.1038/nrc1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson DG. Immunological functions of hyaluronan and its receptors in the lymphatics. Immunol Rev. 2009;230(1):216–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Termeer C, Sleeman JP, Simon JC. Hyaluronan — magic glue for the regulation of the immune response? Trends Immunol. 2003;24(3):112–114. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang D, Liang J, Noble P. Hyaluronan in tissue injury and repair. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:435–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor KR, et al. Recognition of hyaluronan released in sterile injury involves a unique receptor complex dependent on Toll-like receptor 4, CD44, and MD-2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(25):18265–18275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Termeer CC, et al. Oligosaccharides of hyaluronan are potent activators of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;165(4):1863–1870. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Termeer C, et al. Oligosaccharides of Hyaluronan activate dendritic cells via toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med. 2002;195(1):99–111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20001858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tesar BM, Jiang D, Liang J, Palmer SM, Noble PW, Goldstein DR. The role of hyaluronan degradation products as innate alloimmune agonists. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(11):2622–2635. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vasioukhin V, Degenstein L, Wise B, Fuchs E. The magical touch: genome targeting in epidermal stem cells induced by tamoxifen application to mouse skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(15):8551–8556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hathcock KS, Laszlo G, Pucillo C, Linsley P, Hodes RJ. Comparative analysis of B7-1 and B7-2 costimulatory ligands: expression and function. J Exp Med. 1994;180(2):631–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bursch LS, et al. Identification of a novel population of Langerin+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204(13):3147–3156. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Bursch LS, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Langerin expressing cells promote skin immune responses under defined conditions. J Immunol. 2008;180(7):4722–4727. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jameson J, et al. A role for skin gammadelta T cells in wound repair. Science. 2002;296(5568):747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.1069639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheibner KA, Lutz MA, Boodoo S, Fenton MJ, Powell JD, Horton MR. Hyaluronan fragments act as an endogenous danger signal by engaging TLR2. J Immunol. 2006;177(2):1272–1281. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Csoka AB, Frost GI, Stern R. The six hyaluronidase-like genes in the human and mouse genomes. Matrix Biol. 2001;20(8):499–508. doi: 10.1016/S0945-053X(01)00172-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reitinger S, Mullegger J, Greiderer B, Nielsen JE, Lepperdinger G. Designed human serum hyaluronidase 1 variant, HYAL1ΔL, exhibits activity up to pH 5.9. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(29):19173–19177. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.004358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Csoka AB, Frost GI, Wong T, Stern R. Purification and microsequencing of hyaluronidase isozymes from human urine. FEBS Lett. 1997;417(3):307–310. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01309-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Natowicz MR, et al. Clinical and biochemical manifestations of hyaluronidase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(14):1029–1033. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Black CA. Delayed type hypersensitivity: current theories with an historic perspective. Dermatol Online J. 1999;5(1):7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noordegraaf M, Flacher V, Stoitzner P, Clausen BE. Functional redundancy of Langerhans cells and Langerin+ dermal dendritic cells in contact hypersensitivity. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(12):2752–2759. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mummert ME. Immunologic roles of hyaluronan. Immunol Res. 2005;31(3):189–206. doi: 10.1385/IR:31:3:189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alter G, et al. IL-10 induces aberrant deletion of dendritic cells by natural killer cells in the context of HIV infection. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(6):1905–1913. doi: 10.1172/JCI40913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang R, Yan Z, Chen F, Hansson GK, Kiessling R. Hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulphate A rapidly promote differentiation of immature DC with upregulation of costimulatory and antigen-presenting molecules, and enhancement of NF-kappaB and protein kinase activity. Scand J Immunol. 2002;55(1):2–13. doi: 10.1046/j.0300-9475.2001.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rescigno M, Granucci F, Citterio S, Foti M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Coordinated events during bacteria-induced DC maturation. Immunol Today. 1999;20(5):200–203. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(98)01427-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zmolik JM, Mummert ME. Pep-1 as a novel probe for the in situ detection of hyaluronan. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53(6):745–751. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4A6491.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bitter T, Muir HM. A modified uronic acid carbazole reaction. Anal Biochem. 1962;4:330–334. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(62)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee HG, Cowman MK. An agarose gel electrophoretic method for analysis of hyaluronan molecular weight distribution. Anal Biochem. 1994;219(2):278–287. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Nardo A, et al. Cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides block dendritic cell TLR4 activation and allergic contact sensitization. J Immunol. 2007;178(3):1829–1834. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martin SF, et al. Toll-like receptor and IL-12 signaling control susceptibility to contact hypersensitivity. J Exp Med. 2008;205(9):2151–2162. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin H, et al. IL-21R is essential for epicutaneous sensitization and allergic skin inflammation in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(1):47–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI32310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jameson JM, Cauvi G, Witherden DA, Havran WL. A keratinocyte-responsive gamma delta TCR is necessary for dendritic epidermal T cell activation by damaged keratinocytes and maintenance in the epidermis. J Immunol. 2004;172(6):3573–3579. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bobr A, Olvera-Gomez I, Igyarto BZ, Haley KM, Hogquist KA, Kaplan DH. Acute ablation of Langerhans cells enhances skin immune responses. J Immunol. 2010;185(8):4724–4728. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morioka Y, Yamasaki K, Leung D, Gallo RL. Cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides inhibit hyaluronan-induced cytokine release and modulate chronic allergic dermatitis. J Immunol. 2008;181(6):3915–3922. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.