Abstract

Background

The Joint Commission accredits health care organisations in the USA as a prerequisite for licensure. In 2011, TJC published seven Patient Blood Management Performance Measures to improve the safety and quality of care. These Measures will provide hospital-specific information about clinical performance.

Materials and methods

Of the seven TJC PBM Performance Measures, we decided to evaluate PBM-02, “Transfusion indication RBC”, at our hospital. Blood transfusion orders were collected from May 2 to August 2, 2011 and the data analysed.

Results

Of the 724 consecutive red blood cell transfusion orders, 694 (96%) documented both clinical indication and pre-transfusion haemoglobin/haematocrit results. The leading transfusion indication (47% of total) was “high risk patients with pre-transfusion Hb of <9 g/dL”. The majority (72%) of non-actively bleeding patients received a single unit of blood as recommended by our transfusion guidelines. However, 70% of these patients went on to receive additional units and 21% of the initial orders were placed for two or more units. Patients with active bleeding and special circumstances accounted for 17% and 4% of the transfusions, respectively. Our blood utilisation did not change by introducing the single-unit transfusion policy.

Discussion

The majority (96%) of the transfusion orders met The Joint Commission criteria by providing both transfusion indication and pre-transfusion Hb and/or Hct values. Our transfusion guidelines recommend single-unit red blood cell transfusions with reassessment of the patient after each transfusion for need to receive more blood. Although most (72%) initial orders followed our transfusion guidelines, 70% of patients who received a single unit initially went on to receive more blood (some in excess of 10 units). Our objective data may be helpful in evaluating blood ordering practices at our hospital and in identifying specific clinical services for review.

Keywords: blood utilisation, The Joint Commission, Performance Measures, transfusion indications, single-unit policy

Introduction

The Joint Commission (TJC, formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, JCAHO) is a non-profit organisation that accredits health care organisations in the USA1. This accreditation is important in that it is a prerequisite for both licensure and Medicaid payments. In 2011, TJC published seven Patient Blood Management (PBM) Performance Measures as tools for the hospitals to evaluate their processes around blood transfusions (Table I)2. By evaluating these measures, hospitals can compare their performance to others both on state and national levels. TJC will collect and analyse data derived from standardised performance measures in order to improve the quality and safety of transfusions. Importantly, performance measures obtained from individual healthcare organisations may be directly factored into their TJC accreditation process. For these reasons, timely implementation of these Performance Measures is of utmost importance.

Table I.

The Joint Commission Patient Blood Management Performance Measures 2011.

| Transfusion consent (PBM-01) |

| Transfusion indication RBC (PBM-02) |

| Transfusion indication plasma (PBM-03) |

| Transfusion indication platelet (PBM-04) |

| Blood administration documentation (PBM-05) |

| Pre-operative anaemia screening (PBM-06) |

| Pre-operative blood type testing and antibody screening (PBM-07) |

At Monmouth Medical Center (MMC), packed red blood cell (RBC) transfusions account for the majority (~70%) of blood component orders. The number of RBC orders is, therefore, the major driver of transfusion expenses. Recently, a strong, dose-dependent correlation was discovered between RBC transfusions and adverse outcomes such as increased duration of stay in hospital and post-operative morbidity and mortality3,4. In 1988, the National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference of Blood Transfusion Practice Strategies recommended the adoption of a single-unit RBC transfusion policy in non-bleeding patients with chronic anaemia5. It is hoped that this approach will reduce patients’ exposure to non-necessary transfusions and improve clinical outcome. This policy was introduced at MMC on May 1, 2011.

Of the seven TJC Patient Blood Management Performance Measures, we decided to analyse PBM-02 (“Transfusion Indication RBC”) with special regard to adherence to our “one unit at a time” blood transfusion approach. This performance measure was developed by TJC to monitor blood transfusions by clinical indication and pre-transfusion haemoglobin (Hb)/haematocrit (Hct) values2. This measure is based on a study by Friedman and Ebrahim who found an inverse correlation between blood transfusions without documentation of clinical necessity and justification of the transfusion: the greater the number of requests without documentation, the lower the number of justified transfusions6.

Materials and methods

We began collecting data on May 2, 2011 (the day after the new, single-unit transfusion policy was implemented) and completed the study 3 months later (August 2, 2011). During these 3 months, 724 consecutive RBC transfusion orders (excluding those for neonatal intensive care unit patients and young children) were collected and analysed (the paediatric patients receive blood based on their body weight which means fractions of a unit are often used). Monthly RBC transfusion orders before and after the implementation of the single-unit transfusion policy were also reviewed.

Data elements included: (i) clinical indication for RBC transfusion, (ii) pre-transfusion Hb and/or Hct values; and (iii) number of units ordered. Although TJC requires the evaluation of only the first 6 units after admission, we looked at all RBC transfusions during the 3-month study period. This approach has an obvious shortcoming: we did not follow the transfusion history of patients from admission to discharge (or until the 6th unit of blood received) as recommended by TJC. Instead, we limited our study to a somewhat arbitrarily chosen 3-month study period. In other words, our study includes both patients who had been admitted prior to May 2, 2011 and patients who stayed in the hospital (and may have continued receiving transfusions) after the study was completed. Despite these limitations, we believe that our data provide an objective measure of blood utilisation practices at MMC.

For randomly selected patients, we checked the accuracy of pre-transfusion Hb/Hct values in the order form against our Laboratory Information System. However, we did not perform any chart-reviews to verify clinical indications (e.g. active bleeding or history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to render the patient high-risk).

Results

The current transfusion guidelines (transfusion “triggers”) at MMC are listed in Table II. These guidelines are based on clinical indications/symptoms and pre-transfusion Hb and/or Hct values. In patients with chronic anaemia who are not actively bleeding, we recommend that our clinicians administer transfusions one unit at a time, re-evaluate the patient, and then decide if further transfusion is necessary. Consequently, our blood component order form includes all data that are necessary for evaluating PMB-027.

Table II.

Monmouth Medical Center transfusion guidelines.

| Active bleeding (rapid blood loss) |

| Special circumstances (sickle cell crisis and other causes of poor O2 delivery) |

In patients with chronic anaemia who are not actively bleeding, the effective dose is one unit:

|

Of the 724 transfusion orders analysed (TJC denominator), 694 (96%) contained both clinical indication and pre-transfusion Hb/Hct values (numerator statement required by TJC). This represents a significant improvement compared to our previous study in which 13% of orders lacked the indication for transfusion8. The leading transfusion indication (47% of total) was “high risk patient with pre-transfusion haemoglobin of <9 g/dL” (Table III). For randomly selected patients, we checked the accuracy of the pre-transfusion Hb/Hct values provided in the order form and we did not find any significant discrepancies.

Table III.

Blood (RBC) orders between May 2 and August 2, 2011 (3 months).

| Active bleeding | 125 (17%) |

|

| |

| Chronic anaemia patients | |

| Initial order for one unit as recommended | 388 (54%) |

| Hb < 7g/dL (standard risk) | 47 |

| Hb < 9g/dL (high risk) | 337 |

| Hb > 9g/dL | 4 |

| Initial order for two or more units | 152 (21%) |

|

| |

| Special circumstances | 29 (4%) |

|

| |

| No indication provided | 30 (4%) |

Among transfusion indications, active bleeding accounted for 17% of the orders. Moreover, we received 29 orders for “special circumstance” (mostly sickle cell anaemia) patients (Table III). Of the 540 orders placed for patients with chronic anaemia who were not actively bleeding and did not have a special circumstance, 388 (72%) were for a single unit. However, the majority (70%) of these patients subsequently received more blood, some in excess of 10 units (Table IV). Furthermore, 21% of initial orders were placed for two or more units (Table III). Some of these patients may represent patients on chronic transfusion therapy (e.g. those with myelodysplastic syndrome).

Table IV.

Follow-up of 315 of the 388 patients who initially received a single-unit transfusion as recommended (see Note 1).

| 94 patients | single-unit transfusion |

| 94 patients | two units of blood |

| 41 patients | three units of blood |

| 35 patients | four units of blood |

| 36 patients | five to nine units of blood |

| 15 patients | ten or more units of blood |

| Conclusion: 70% of patients who initially received a single unit transfusion went on to receive more blood. | |

Note 1 - Seventy-three of the 388 patients transfused one unit blood initially were re-classified either as “active bleeding” or “special circumstances” when additional blood was ordered. Since our one-unit recommendation does not apply to these indications, we decided to exclude these patients from the follow-up.

Note 2 - Patients were not followed from admission to discharge. These numbers reflect only blood orders submitted between May 2 and August 2, 2011. Consequently, the number of transfusions per patient could be even higher.

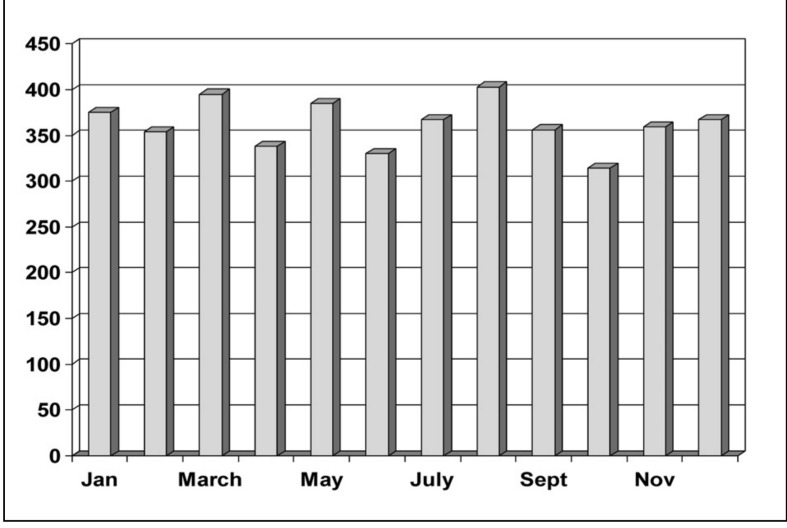

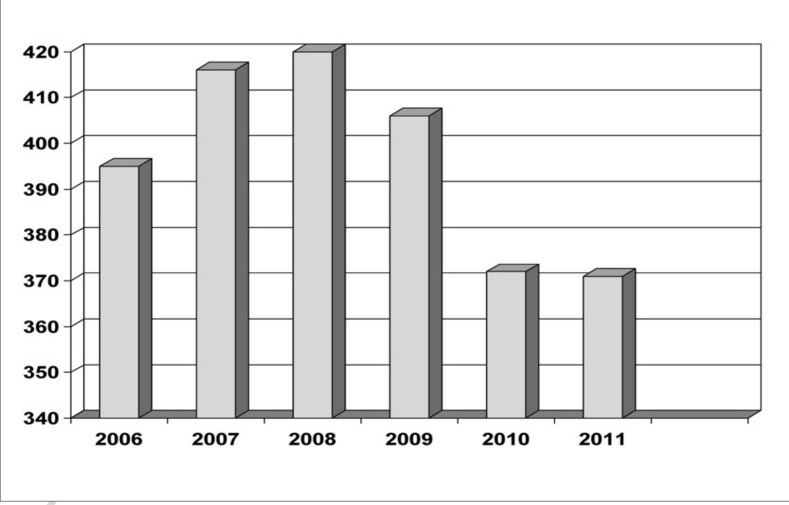

The ultimate goal of the single-unit transfusion policy is to prevent unnecessary transfusions. As a surrogate measure, we looked at the number of monthly RBC transfusions before and after the implementation of this policy and did not detect any significant changes: the monthly average was 366 and 361 before and after the implementation of the single-unit transfusion policy, respectively (Figure 1). Consequently, this change in transfusion guidelines did not reduce our annual blood utilisation (Figure 2). This is in contrast to the ~9% decrease that followed the introduction of our new, four-tiered transfusion guidelines (Table II) in 2009 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Monthly packed RBC transfusions at MMC in 2011.

Figure 2.

Monthly average of packed RBC transfusions at MMC between 2006 and 2011.

Discussion

For many decades, it was a common practice to transfuse patients with a Hb of less than 10 mg/dL or a Hct of less than 30. This practice is appealing since the “10/30 rule” is simple and easy to remember. However, this practice is not based on evidence that it improves patient outcome. Quite the contrary, it exposes patients to adverse events and incurs wasteful use of already scarce resources. In other words, transfusions may actually harm, even kill, rather than help, patients9.

In 2009, we introduced new transfusion guidelines (“triggers”) by adapting the recommendations of Dr. Patricia Ford, the Past President of the Society for the Advancement of Blood Management (personal communication at the Annual Meeting of the New Jersey Association of Blood Bank Professionals, 2006). Most importantly, we reduced the trigger of blood transfusions in hospitalised, haemodynamically stable, normovolaemic, symptomatic chronic anaemia patients from 8 to 7 g/dL8. After this change, our blood utilisation decreased by ~9% (Figure 2)8. During this study we noted that a slight majority of blood orders (55% of total) were for two or more units8. Therefore, on May 1, 2011 we implemented a change promoted by the National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference on Blood Transfusion Practice Strategies5: now we ask our clinicians to administer blood one unit at a time, measure the post-transfusion Hb/Hct, re-evaluate the patient, and then decide if further transfusion is necessary. The rationale behind this change was explained to our medical staff (continuous medical education activities) and then reinforced by sending educational material via e-mail blast and regular mail.

Independently of our efforts, in 2011 TJC published its seven Patient Blood Management Performance Measures to prevent unnecessary transfusions (Table I)2,7. TJC will collect data and make it available to hospitals so that hospitals can compare their performance to that of their peers at both the local and national levels. Furthermore, TJC may directly factor the performance measure data into the accreditation process. In anticipation of these changes, we decided to evaluate Patient Blood Management Performance Measure PMB-02 (“Transfusion indication RBC”) at our institution to see how we are doing.

We detected a significant improvement in submitting complete blood orders (the proportion of incomplete orders decreased from 13% in 2009 to 4% in 2011). The most recent implementation of the electronic order system at our hospital will, it is hoped, eliminate incomplete orders completely.

In 2009, 55% of the total blood orders were for two or more units8. This showed a modest improvement after the implementation of our single-unit transfusion policy: in 2011, 54% of all orders (and 72% of orders in non-bleeding patients) were placed for one unit of blood (Table III). However, the majority of patients (70%) transfused with one unit of blood subsequently received additional units (Table IV).

Importantly, our blood utilisation did not improve after the single unit policy was implemented (Figures 1 and 2). This indicates that transfusion practices at MMC did not change perceptibly despite the change in transfusion policy. Thus, our experience is in contrast to others in the literature in which significant improvement was reported10. Medical practice is notoriously slow to change and the lack of reduction in our blood utilisation may, therefore, simply reflect the very short time (3 months) that has elapsed between implementation of our single-unit policy and completion of this study. Furthermore, we allow our clinicians to start with two or more units of blood transfusion in non-bleeding chronic anaemia patients. Indeed, 21% of the initial blood orders were for two or more units (Table III). In a very recent Swiss study, Berger and colleagues reported a 25% reduction in blood utilisation 4 years after implementing a single-unit transfusion policy11. However, in this study (unlike in ours) the single unit policy was strictly enforced.

In one study, the overuse of RBC transfusions was estimated to be as high as 23%12. In 2011, an International Consensus Conference on Transfusion Outcomes Group rated blood transfusions as “inappropriate” in all patients with a Hb level of 10 g/L or higher13. During the study period, we received only one order belonging to this category. Furthermore, the same Group considered transfusions inappropriate in the majority (~70%) of patients whose Hb fell in the range of 8 to 9.9 g/dL. This category would include almost half of our transfused chronic anaemia patients! We believe that auditing some of the transfusions (e.g. by chart review) in this category of patients may provide useful information on the transfusion practices (appropriate versus uncertain versus inappropriate) at our hospital.

This study was only meant to be a somewhat crude “gap analysis” that is a snapshot of where we are now and where we need to get to. A more detailed analysis is beyond the capabilities of our Blood Bank. We believe that an oversight committee needs to be formed (probably at Corporate level) with a written plan for data gathering, data analysis and corrective actions.

Footnotes

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.The Joint Commission Standards. [Accessed on 20 April 2012]. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/standards.

- 2.Gammon HM, Walters JH, Watt A, et al. Developing performance measure for patient blood management. Transfusion. 2011;51:2500–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isbister JP, Shander A, Spahn DR, et al. Adverse blood transfusion outcomes: establishing causation. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferraris VA, Davenport DC, Saha SP, et al. Surgical outcomes and transfusion of minimal amounts of blood in the operating room. Arch Surg. 2012;147:49–55. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Consensus conference. Perioperative red blood cell transfusion. J Am Med Assoc. 1988;260:2700–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman MT, Ebrahim A. Adequacy of physician documentation of red blood cell transfusion and correlation with assessment of transfusion appropriateness. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:474–9. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-474-AOPDOR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Joint Commission (library of measures) Implementation Guide for The Joint Commission Patient Blood Management Performance Measures. 2011. [Accessed on 20 April 2012]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ansari S, Szallasi A. Blood management by transfusion triggers: when less is more. Blood Transfus. 2012;10:28–33. doi: 10.2450/2011.0108-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vamvakas EC, Blajchman MA. Blood still kills: six strategies to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion-related mortality. Transfus Med Rev. 2010;24:77–124. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma M, Eckert K, Ralley F, Chin-Yee I. A retrospective study evaluating single-unit red blood cell transfusions in reducing allogeneic blood exposure. Transfus Med. 2005;15:307–17. doi: 10.1111/j.0958-7578.2005.00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger MD, Gerber B, Am K, et al. Significant reduction of red blood cell transfusion requirements by changing from a double-unit to a single-unit transfusion policy in patients receiving intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2012;97:116–22. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.047035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barr PJ, Donnelly M, Cardwell CR, et al. The appropriateness of red blood cell use and the extent of overtransfusion: right decision? Right amount? Transfusion. 2011;51:1684–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shander A, Fink A, Javidroozi M, et al. Appropriateness of allogeneic red blood cell transfusion: the International Consensus Conference on Transfusion Outcomes. Transfus Med Rev. 2011;25:232–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]