Abstract

Objective

Osteoarthritis (OA) is currently diagnosed using clinical and radiographic findings. In recent years MRI use in osteoarthritis has increasingly been studied. This study was conducted to determine the diagnostic utility of MRI in OA through a meta-analysis of published studies.

Methods

A systematic literature search was undertaken to include studies that used MRI to evaluate or detect osteoarthritis. MRI was compared to various reference standards: histology, arthroscopy, radiography, CT, clinical evaluation, and direct visual inspection. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area under the curve were calculated. Random effects models were used to pool results.

Results

Of 20 relevant studies identified from the literature, 16 reported complete data and were included in the meta-analysis, with a total of 1220 patients (1071 with OA and 149 without). Overall sensitivity from pooling data of all the included studies was 61% (95% confidence interval [CI] 53 to 68), specificity was 82% (95% CI 77 to 87), PPV was 85% (95% CI 80 to 88), and NPV was 57% (95% CI 43 to 70). The ROC showed an area under the curve of 0.804. There was significant heterogeneity in the above parameters (I2 >83%). With histology as the reference standard, sensitivity increased to 74% and specificity decreased to 76% compared with all reference standards combined. When arthroscopy was used as the reference standard, sensitivity increased to 69% and specificity to 93% compared with all reference standards combined.

Conclusion

MRI can detect OA with an overall high specificity and moderate sensitivity when compared with various reference standards, thus lending more utility to ruling out OA than ruling it in. The sensitivity of MRI is below the current clinical diagnostic standards. At this time standard clinical algorithm for OA diagnosis, aided by radiographs appears to be the most effective method for diagnosing OA.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, diagnosis, MRI

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a disease of the synovial joint tissues in which there is destruction of synovial joint tissues and active, but ineffective attempts at repair.1 This structural change can lead to pain and disability. In fact, the risk for disability caused by OA is on par with that of cardiovascular disease and greater than that due to any other medical condition in the elderly.2 Despite this, the etiology and pathology of OA are not well understood. This contributes to the discrepancy between pathological evidence for the disease and clinical symptoms.3 Because of this inconsistency, no single measure is used for diagnosis in OA, but rather a combination of tools, which yields better diagnostic performance than does any one of those tools on its own.

Currently, the diagnosis of knee OA in the clinic is most often made using the 1986 criteria of the American College of Rheumatology. These criteria include a combination of the patient’s age, signs and symptoms on physical exam, radiographic and/or laboratory evidence.4 When the radiograph is used along with physical exam, the sensitivity and specificity of this method are 91% and 86%, respectively. Using a classification and regression tree technique (CART) with clinical, radiographic and laboratory evidence raises the sensitivity and specificity into the mid-eighty to mid-ninety percent range.4 These diagnostic techniques are relatively inexpensive and readily available. More recently, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) OA Task Force suggested that a confident clinical diagnosis of knee OA may be made according to 3 symptoms (persistent knee pain, morning stiffness and reduced function) and 3 signs (crepitus, restricted movement and bony enlargement).5 Although the ACR or EULAR criteria remain the standard for diagnosis both in the clinic and in research, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been increasingly used as well.6

Before widespread use of MRI in clinical practice is adopted reasoned debate of the strengths and weaknesses of this method should be considered. Cost concerns, lack of clarity about diagnostic performance and little standardization regarding MRI interpretation has made it unclear whether this increased use of MRI in clinical practice is rational. In contrast to x-ray, MRI can visualize all tissues in the joint involved in OA: cartilage, menisci, bone, and soft tissue. In addition, MRI causes no ionizing radiation exposure. While it does not have the distortions and magnification problems inherent in radiographs, MRI does have its own motion and susceptibility artifacts. MRI also requires several different pulse sequences to visualize specific tissue types, and its use requires determining the best sequences for various features. Since 1988, numerous studies have examined the use of MRI in imaging synovial inflammation, meniscus pathology, cartilage morphology alteration, bone marrow lesions, osteophytes, cartilage composition, and other markers along with their correlation with clinically defined OA.7 The predictive value and diagnostic performance of some of these markers has also been studied.8,9

One hope in testing the diagnostic utility of MRI in OA is to find and use some of those features undetectable by other imaging modalities, thus potentiating an earlier diagnosis of OA or a diagnosis of pre-osteoarthritis (pre-OA), in those patients lacking clinical symptoms. This would allow for therapeutic trials aimed at altering the preliminary course of OA and attempting to prevent many of the later degenerative changes which have already occurred once the disease is detected by clinical exam and radiographic change. Such an early diagnosis has not been possible with the current standard techniques discussed above. However a recent study has proposed a definition of OA based on MRI using the Delphi method in an attempt to move towards detecting earlier disease.10

Despite the growing pool of information, there is little uniformity in the diagnostic application of MRI and a lack of its confirmed diagnostic utility, as noted in the “Evidence Based Recommendations for the Diagnosis of Knee OA” published by EULAR in 2009.5 Over the last decade we have gained a better understanding of the many individual features on MRI, their clinical and pathologic significance, and how to use many of them quantitatively.11 As yet however the diagnostic performance of MRI for OA has not been adequately studied. The objective of this meta-analysis was to evaluate, and determine the factors affecting, the diagnostic performance of MRI in the setting of OA.

Methods

1. Systematic literature search

An online literature search was conducted of the OVID MEDLINE (1945-), Embase (1980-), and Cochrane databases (1998-) of articles published up to the time of the search, April 2009, with the search entries “MRI”, and “osteoarthritis”, “osteoarthritides”, “osteoarthrosis”, “osteoarthroses”, “degenerative arthritis”, “degenerative arthritides”, or “osteoarthritis deformans”. The abstracts of the 1330 citations received with this search were then preliminarily screened for relevance by two reviewers (KH and DJH). For this preliminary search, all articles which used MRI, in some form, on patients with osteoarthritis of the knee, hip, or hand were included. Although review articles were not included (see inclusion/exclusion criteria), citations found in any review articles which were not already included in our preliminary search were screened for possible inclusion in this study. This added 7 more relevant studies to our search. One further article was added by one of the authors of this meta-analysis bringing the preliminary total to 1338.

2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Only studies published in English were included. Studies presenting non-original data were excluded, such as reviews, editorials, opinion papers, or letters to the editor. Studies using non-human subjects or specimens were excluded. Studies in which rheumatoid, inflammatory, or other forms of arthritis were incorporated in the OA datasets were excluded, as well as general joint-pertinent MRI studies not focused on OA. Studies with no extractable, numerical data were excluded. Only those articles which had some measure of diagnostic performance were included. Any duplicates which came up in the preliminary search were excluded.

For the meta-analysis, only those articles from the systematic review were included that had complete sensitivity and specificity data needed to derive the true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), and false negative (FN) values for that study.

3. Data abstraction

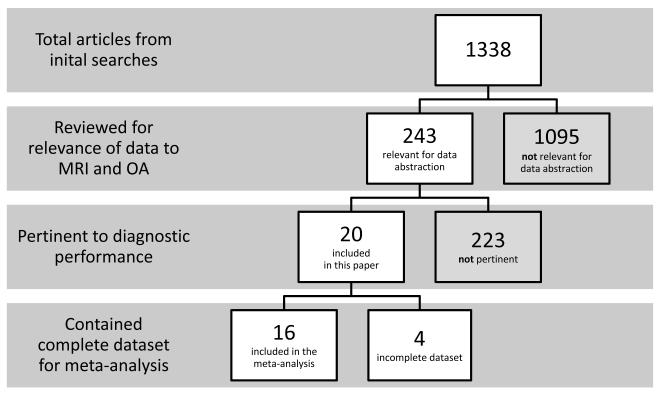

Of the preliminary 1338 abstracts, 243 were selected for data abstraction of which 22 were pertinent to diagnostic performance (Figure 1). Two of these studies were excluded as they used MRI as the reference standard against which x-ray techniques were compared,12,13 leaving 20 studies. Two reviewers (KH and LM) independently abstracted the following data: 1) patient demographics and inclusion/exclusion criteria; 2) MRI make, sequences and techniques used, tissue types viewed; 3) study type and funding source; 4) MRI reliability/reproducibility data; 5) which diagnostic measures were used with MRI (e.g. cartilage thickness measurements, lesion identification, etc.) and their diagnostic performance (e.g. sensitivity, specificity, etc.) when compared with a reference standard; 6) the reference standard measures against which the MRI measure was evaluated; 7) treatment and MRI measures (when appropriate).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the screening process for articles included in the systematic review.

4. Assessment of study quality

Quality and bias assessment of the studies was performed using the Downs Methodological Study Criteria.14

5. Outcome measures

The focus of this analysis was on diagnostic performance. Data extracted on the diagnostic performance of MRI or material pertaining to defining OA on MRI was used. The ability of MRI to discriminate between patients with and without OA (OA in this case is defined by either clinical diagnosis, radiography, or both) was summarized by sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV, NPV), positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+, LR−) and accuracy. A LR+ above 10 or LR− below 0.1 is considered strong evidence to respectively rule in or rule out a diagnosis in most circumstances. The term “overall sensitivity” (or specificity, etc.) is used to describe the results from pooling of all the TP, FP, TN, FN data gathered from the studies included, regardless of the reference standard and tissue type used.

6. Data analysis

The TP, FP, TN, FN values were derived from the sensitivity and specificity data and from the numbers of subjects reported in each study. From these the point estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV were calculated. Positive and negative likelihood ratios were computed using the standard formulas: LR+ = sensitivity/(1-specificity) and LR− = specificity/(1-sensitivity). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve or AUC was also calculated. ROC presents a curve of sensitivity (y-axis) against 1-specificity (x-axis) at different cut-off points (e.g., deciles) of the MRI measures. ROC quantifies the overall ability of a diagnostic test to classify diseased and non-diseased individuals correctly. Larger values of ROC (range between 0 to 1) indicate good discriminative power.15 The DerSimonian and Laird method16 for random-effects models was used to pool individual estimates. Heterogeneity was assessed across the studies using the Cochran Q statistic and inconsistency, I2 which represents the percent variance across all studies attributable to heterogeneity rather than to chance; a higher value indicates more heterogeneity.17 Random-effects models and inconsistency were calculated for the sub-groups of histology, arthroscopy, and x-ray as reference standards. Statistical significance was set at 0.05 and CIs calculated at 95%.

Results

We identified 20 studies which met our inclusion criteria and contained relevant diagnostic measure and performance data.8,9,18-35 Study attributes and population characteristics are presented in Table 1. The studies included a total of 1559 patients, 1396 with OA and 163 without OA. A large majority of the studies used semi-quantitative MRI measurement techniques for measuring OA (Table 2). Various tissues were imaged in the different studies. Cartilage was examined in the majority of studies (16 studies, Table 2). The other commonly viewed tissue types were meniscus (8), synovium (2), bone (3), and bone marrow lesions (3). As the reference standard measure against which the MRI diagnostic techniques were compared, arthroscopy was used most prevalently, followed by histological section and x-ray (Table 3).

Table 1.

Study attributes and population characteristics

| REFERENCE | Total sample |

# of cases |

# Of controls |

Age (years), Mean±SD, [Range] |

# (%) of females |

Measurement technique used |

Reference standard used |

Tissue type(s) imaged | Study design | Downs score |

Joint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hodler J; Radiology; 1992; 1609084 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 73.8, [56-88] | 3 (30) | Semiquantitative | Histology | Meniscus | Cross-sectional | 6 | Knee |

| Recht MP; Radiology; 1993; 8475293 | 10 | 10 | 0 | [70-89] | N/A | Semiquantitative

and descriptive |

Open visualization | Cartilage | Other | 5 | Knee |

|

Disler DG;

AJR Am J Roentgenol.; 1996; 8659356 |

47 | 32 | 15 | 36, [7-67] | 14 (30) | Semiquantitative | Arthroscopy | Cartilage | Cross-sectional | 6 | Knee |

|

Leunig M;

Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery- British Volume;

1997; 9119848 |

23 | 5 | 18 | 40±2 | 14 (61) | Semiquantitative | Open visualization | Acetabular labrum | Cross-sectional | 5 | Hip |

| Trattnig S; Journal of Computer

Assisted Tomography; 1993; 9448754 |

20 | 20 | 0 | 72,2, [62-82] | 18 (90) | Semiquantitative | Histology | Cartilage | Other | S | Knee |

|

Kawahara Y;

Acta Radiologica; 1998; 9529440 |

72 | 72 | 0 | 58, [41-74] | 46 (64) | Semiquantitative | Arthroscopy | Cartilage | Other | 6 | Knee |

|

Uhl M;

British Journal of Radiology; 1998; 9616238 |

24 | 24 | 0 | [45-68] | N/A | Semiquantitative | Histology | Cartilage | Other | 6 | Knee |

|

Boegard T;

Acta Radiologica -Supplementum; 1998 ; 9759121 |

57 | 57 | 0 | N/A | N/A | Semiquantitative | X-ray | Cartilage, meniscus,

bone, subchondral lesions |

Longitudinal Prospective |

5 | Knee |

|

Bachmann

GF; European Radiology; 1999; 9933399 |

320 | 240 | 80 | 29.3±8.7, [13-56] | 122 (38.1) | Semiquantitative | Arthroscopy | Cartilage, meniscus | Cross-sectional | 7 | Knee |

|

Plotz GM;

Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery - British Volume;

2000 ; 10813184 |

15 | 15 | 0 | N/A | 9 (60) | Semiquantitative | Histology | Acetabular labrum | Other | 7 | Hip |

|

Yoshioka H;

Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging; 2004 : 15503323 |

16 | 16 | 0 | 55.6, [40-73] | 6 (38) | Quantitative

and semiquantitative |

Arthroscopy | Cartilage, synovium,

BML, meniscus |

Other | 5 | Knee |

|

Nishii T;

American Journal of Roentgenology; 2005 ; 16037508 |

18 | 10 | 8 | [12-49] | 17 (94) | Semiquantitative | Computed Tomography (CT) |

Cartilage | Cross-sectional | 6 | Hip |

|

Hunter DJ;

Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2006; 16868968 |

264 | 264 | 0 | 66.7±9.2. [47-93] | 108 (40.9) | Semiquantitative and quantitative meniscal position |

X-ray | Cartilage, meniscus | Cross-sectional | 9 | Knee |

|

Bruyere O;

Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2007; 16890461 |

62 | 62 | 0 | 64.9±10.3 | 46 (74) | Semiquantitative | X-ray | Cartilage, synovium, bone,

BML, meniscus, ligament |

Longitudinal Prospective | 10 | Knee |

|

Oda H:

Journal of Orthopaedic Science; 2008; 18274849 |

161 | 161 | 0 | 58.5, [11-85] | 98 (60.9) | Semiquantitative | X-ray | Effusion, meniscus, ligament,

bone bruises |

Cross-sectional | 8 | Knee |

|

Saadat E;

European Radiology: 2008; 18491096 |

7 | 7 | 0 | 65.6 | 4 (57) | Semiquantitative | Histology | Cartilage | Other | 5 | Knee |

|

Mutimer J;

Journal of Hand Surgery; 2008; 18562375 |

20 | 20 | 0 | 47, [26-69] | 9 (45) | Semiquantitative | Arthroscopy | Cartilage | Cross-sectional | 6 | Hand |

|

Li W;

Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging; 2009; 19161210 |

31 | 17 | 14 | Cases: 61.8, [40-36]; controls: 29.2, [18-40] |

21 (68) | Compositional technique (dGEMRIC) |

Clinical | Cartilage | Case control | 7 | Knee |

| Kijowski R.; Radiology; 2009; 19164121 | 200 | 200 | 0 | 1.5T image group: 38.9, [16-63]; 3T image group: 39.1, [15-65] |

87 (43.5) | Semiquantitative | Arthroscopy | Cartilage | Longitudinal Retrospective |

10 | Knee |

|

Madan-Sharma

R; RSNA 2009; LL-MK2083-R02 |

182 | 154 | 28 | Case group: 56(Range: 45-65); Control group: 59(Range: 44-75) |

Case group: 120 (80); Control group: 21 (75) |

Semiquantitative | Clinical | Cartilage, bone, BML,

meniscus, cysts, effusions |

Case control | 11 | Knee |

Table 2.

Measurement used and tissue type imaged by MRI in all 20 studies

| No. of studies | % of studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement | Quantitative Cartilage | 1 | 5 |

| Compositional technique* | 1 | 5 | |

| Semi-quantitative | 19 | 95 | |

| Descriptive | 1 | 5 | |

| Quantitative meniscal position | 1 | 5 | |

|

| |||

|

Synovial Joint

Tissue |

Cartilage | 16 | 80 |

| Synovium | 2 | 10 | |

| Bone | 3 | 15 | |

| Bone marrow lesions | 3 | 15 | |

| Meniscus | 8 | 40 | |

| Ligaments | 2 | 10 | |

| Other | 7 | 35 | |

dGEMRIC MRI enhancement for viewing of proteoglycan content of cartilage

Table 3.

Reference standard used for MRI technique comparison and synovial joint tissue assessed: number of individual datasets and studies (including all 20 studies)

|

Reference

standard used |

Tissue

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | Cartilage | Labrum | Meniscus | Other | Total datasets |

Total studies |

|

| Arthroscopy | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| X-ray | 3 | 11 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 20 | 4 |

| Histology | 0 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 5 |

| Direct Visualization |

0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| CT | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Clinical | 7 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 14 | 2 |

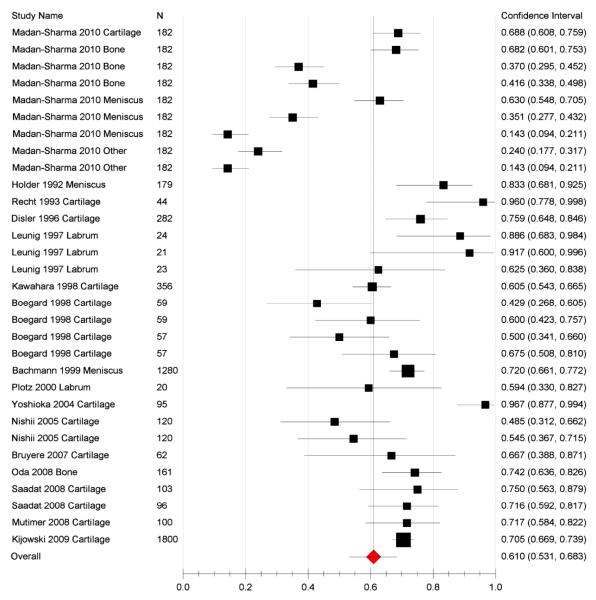

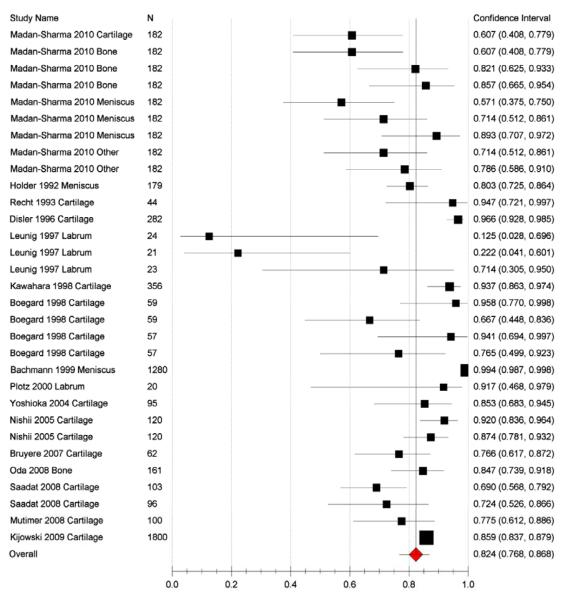

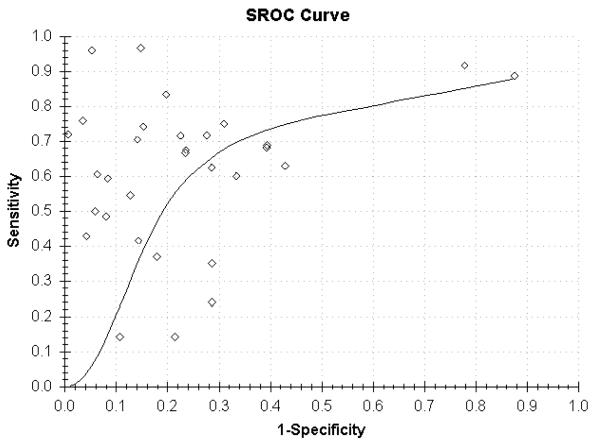

16 of the original 20 papers were included in the meta-analysis because 4 lacked complete sensitivity and specificity data needed to derive the TP, FP, TN, FN data.8,24,25,35 A total of 1220 patients were included in the meta-analysis, 1071 with OA and 149 without OA. In 5 of the 16 studies more than one parameter was analysed (e.g. tissue type, defined endpoint) which created separate datasets in our analyses.9,21,22,29,33 Overall sensitivity of all the datasets from the random effects model was 61% (95% CI 53-68) (Figure 2), specificity from the random effects model was 82% (95% CI 77-87) (Figure 3), PPV was 85% (95% CI 80-88), and NPV 57% (95% CI 43-70; Table 4). LR+ was 3.22 (95% CI 2.33-4.45) and LR− was 0.48 (95% CI 0.40-0.59). Overall accuracy was 69% (95% CI 61-76). An ROC curve showed an area under the curve of 0.804 (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Plot showing sensitivity of MRI use in OA viewing various tissue types in the 16 studies with complete data

Figure 3.

Plot showing specificity of MRI use in OA viewing various tissue types in the 16 studies with complete data

Table 4.

Random effects model for all tissue types and all reference standards in the 16 studies with complete data: DerSimonian-Laird

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Lower | Upper | 1^2 | P-Value | |

| Specificity | 0.824 | 0.768 | 0.868 | 0.850 | <0.001 |

| Sensitivity | 0.610 | 0.531 | 0.683 | 0.938 | <0.001 |

| PV+ | 0.846 | 0.799 | 0.884 | 0.833 | <0.001 |

| PV− | 0.570 | 0.427 | 0.702 | 0.977 | <0.001 |

| Accuracy | 0.692 | 0.610 | 0.763 | 0.970 | <0.001 |

| DOR | 7.874 | 4.688 | 13.226 | 0.891 | <0.001 |

| LR+ | 3.218 | 2.328 | 4.450 | 0.901 | <0.001 |

| LR− | 0.484 | 0.400 | 0.586 | 0.914 | <0.001 |

Figure 4.

Plot of summary receiver operating characteristics curve (ROC) comparing MRI techniques other reference with standards in the 16 studies with complete data: x-ray, clinical diagnosis, arthroscopy, histology, direct visualization, and CT scan. Diagnostic accuracy is demonstrated by plotting 1-specificity (x axis) versus sensitivity (y axis). The area under the curve (AUC) is 0.804.

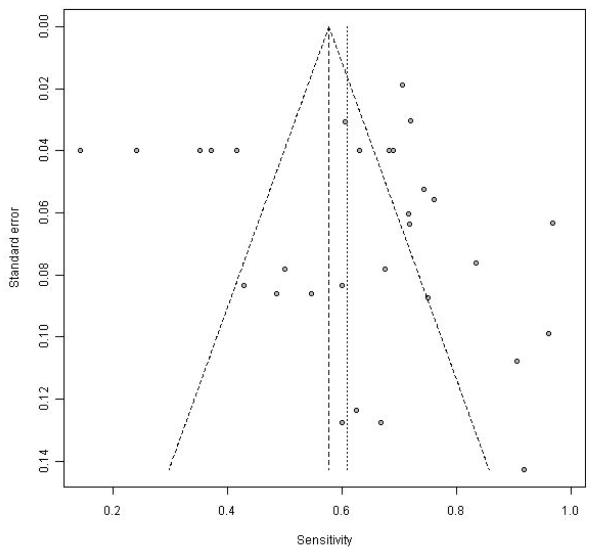

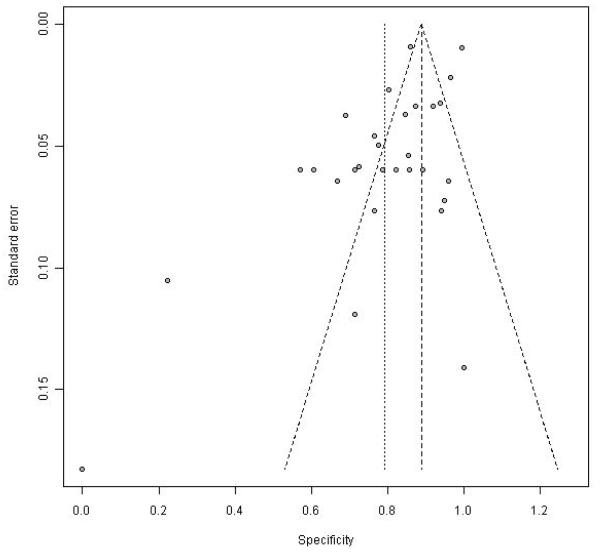

There was significant heterogeneity in all of the parameters listed above (I2 > 83%). Consistent with this, the funnel plots including all the data show marked variability for individual point estimates, more so with sensitivity than specificity (Figure 5 and 6).

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of sensitivity in the 16 studies with complete data

Figure 6.

Funnel plot of specificity in the 16 studies with complete data

The diagnostic performance of MRI varied markedly depending on which reference standard it was compared to. In general the MRI sensitivity was better when it was compared to the tissue of interest directly (e.g. arthroscopy, histology, open inspection) as distinct from x-ray and clinical information, whereas specificity was superior with arthroscopy, worst with open inspection, with histology and x-ray in between. Using histology as the reference standard the sensitivity increases to 74% (95% CI 65-81) while the specificity decreases to 76% (95% CI 67-82; Table 5). Sensitivity and specificity are comparable to the overall values when using radiography as the reference standard (Table 6). With arthroscopy as the reference standard, both sensitivity and specificity increase to 69% (95% CI 62-75) and 93% (95% CI 86-96), respectively (Table 7). When using only the clinical information as the reference standard, specificity is slightly decreased to 73% (95% CI 64-80), while sensitivity is markedly decreased to 39% (95% CI 26-54). Lastly, with open visual inspection of the tissues as reference standard the sensitivity increases to 86% (CI 65-96), while the specificity drops to 56% (CI 15-91).

Table 5.

Random effects model of diagnostic data for all tissue types, using histology as the reference standard (5 datasets from 4 studies): DerSimonian-Laird

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Lower | Upper | 1^2 | P-Value | |

| Specificity | 0.755 | 0.675 | 0.820 | 0.520 | 0.244 |

| Sensitivity | 0.737 | 0.648 | 0.810 | 0.469 | 0.288 |

| PV+ | 0.704 | 0.484 | 0.858 | 0.883 | 0.001 |

| PV− | 0.759 | 0.446 | 0.925 | 0.945 | <0.001 |

| Accuracy | 0.745 | 0.679 | 0.802 | 0.628 | 0.146 |

| DOR | 10.030 | 5.361 | 18.765 | 0.474 | 0.283 |

| LR+ | 3.122 | 2.193 | 4.444 | 0.593 | 0.179 |

| LR− | 0.353 | 0.265 | 0.471 | 0.342 | 0.386 |

Table 6.

Random effects model of diagnostic data for all tissue types, using x-ray as the reference standard (6 datasets from 3 studies): DerSimonian-Laird

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Lower | Upper | 1^2 | P-Value | |

| Specificity | 0.809 | 0.711 | 0.879 | 0.544 | 0.119 |

| Sensitivity | 0.607 | 0.497 | 0.708 | 0.708 | 0.017 |

| PV+ | 0.816 | 0.658 | 0.910 | 0.790 | 0.002 |

| PV− | 0.615 | 0.474 | 0.739 | 0.817 | 0.001 |

| Accuracy | 0.698 | 0.633 | 0.757 | 0.598 | 0.076 |

| DOR | 8.389 | 4.517 | 15.583 | 0.425 | 0.224 |

| LR+ | 3.280 | 2.129 | 5.053 | 0.495 | 0.160 |

| LR− | 0.475 | 0.376 | 0.602 | 0.572 | 0.096 |

Table 7.

Random effects model of diagnostic data for all tissue types, using arthroscopy as the reference standard (11 datasets from 7 studies): DerSimonian-Laird

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Lower | Upper | 1^2 | P-Value | |

| Specificity | 0.926 | 0.857 | 0.963 | 0.928 | <0.001 |

| Sensitivity | 0.687 | 0.617 | 0.749 | 0.826 | <0.001 |

| PV+ | 0.869 | 0.766 | 0.931 | 0.915 | <0.001 |

| PV− | 0.826 | 0.699 | 0.907 | 0.975 | <0.001 |

| Accuracy | 0.841 | 0.761 | 0.897 | 0.966 | <0.001 |

| DOR | 32.110 | 12.682 | 81.300 | 0.926 | <0.001 |

| LR+ | 9.280 | 4.776 | 18.033 | 0.923 | <0.001 |

| LR− | 0.357 | 0.290 | 0.440 | 0.825 | <0.001 |

The agreement for assessing bias by the data extraction readers was kappa = 0.70.

Discussion

This study examines the diagnostic performance of MRI in OA compared with other clinical and research reference standards for viewing synovial joint structural change. The comparative reference standards have themselves relative merits when used for testing MRI techniques. Firstly, arthroscopy and histology, because they view cartilage and other joint tissues directly, are most suitable for judging the performance of MRI in imaging cartilage changes or meniscal degeneration. However, viewing cartilage defects directly may or may not correlate with actual clinical OA diagnosis. X-ray, on the other hand, cannot view cartilage directly, but provides an indirect representation of cartilage integrity through assessment of joint space width. This provides a poor reference standard with which to grade cartilage defects, as a lack of change in joint space width does not preclude possible cartilage defects on MRI.8 X-ray also visualizes osteophytes, changes in bone contour and sclerosis. Because the Kellgren Lawrence scale is comprised of these four characteristics and has been used in OA definition, correlation with radiographic findings could lend utility to MRI in OA diagnosis.

The specificity is generally superior to sensitivity for nearly all datasets in the studies included, suggesting that, based on the MRI features used, MRI would be more useful in ruling out false positives when a patient is already suspected of having OA by other measures. However, because current diagnosis is performed with clinical and radiologic means, until there is a separate, well validated MRI-based definition of OA, only those diagnostic measures based on reference standards of arthroscopic or histologic definitions of OA can add to a diagnosis made with the present diagnostic standards.

Not surprisingly, diagnostic performance, and more precisely sensitivity is better with arthroscopy and histology as reference standards compared with x-ray because they directly visualize cartilage, as does MRI.

Because of its lower sensitivity compared to ACR clinical criteria as measured by even the more robust reference standards (e.g. arthroscopy and histology), MRI is not currently useful as a preliminary screen for identifying new cases of OA. Its lack of utility in this case is especially clear given that for OA of the knee the much cheaper, presently-used diagnostic tools of history, exam, and radiography provide a better sensitivity: radiograph plus physical exam at 91% and the classification and regression tree technique from mid eighty to mid ninety percent.4 In providing more clinical utility, likelihood ratios >10 and <0.1 are needed for strong evidence in respectively ruling in or out a diagnosis, and most of those found in this study are far from providing such support for a diagnosis either way.36 A well validated MRI-based definition of OA is needed before it can supersede the current methods of diagnosis, and for this the correct constellation of MRI features must be found to raise the sensitivity and specificity of this imaging modality.

Radiography is currently used as a confirmatory finding in the clinical diagnosis of OA, as well as to rule out other possible diagnoses when a thorough history and physical exam proves ambiguous. Even if MRI had the needed sensitivity to detect early OA before it appears symptomatically in the clinic, or if it could inform us on the stage of the disease from an anatomical or pathological standpoint, it would still provide no therapeutic advantage as there are currently no available disease modifying therapies for OA. In addition MRI carries with it a large cost; an MRI of the knee costs approximately 5-22 times that of a standard radiograph in many health care settings.37,38 Given the prevalence of OA in the general population, use of MRI in this setting would come at a great expense. The only setting in which the use of MRI may be beneficial is in cases in which other diseases are high on the differential, and they can be ruled out on MRI, or treated if present, e.g. early stage avascular necrosis. Any argument for MRI use in OA diagnosis needs to show a clear therapeutic benefit to make up for the large escalation in cost.

There were clearly some limitations to this study. The many different MRI sequences used, the different tissues used, and the various reference standards limit the usefulness and meaningfulness of any single value for sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, LR+, and LR-. Ideally the many studies would have used the same parameters, tissue types and MRI sequences, to obtain a more powerful and homogeneous diagnostic value. In addition, the studies examined each had variations in the severity of OA included, affecting their diagnostic measurements; it was beyond the scope of this analysis to draw distinctions between degrees of OA and the effect of these gradations on MRI performance. More than half of the studies assessed joint regions or counted the number of total defects noted rather than numbers of total joints or numbers of patients.18-20,23,26,28,29,31,33,34 This skewed the weight of each datapoint in the meta-analysis; ideally all of the studies would have one datapoint per subject, or an equal number of surfaces analysed per subject.

Due to the number of existing studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria found in our search and their differing approaches, the conclusions we can draw about detailed aspects of OA diagnosis have limitations. In current clinical practice, diagnostic needs which MRI could theoretically fill are in differential diagnosis (e.g. avascular necrosis), differentiation of OA into subcategories/phenotypes, and in diagnosing a pre-OA state, i.e. identifying structural change in patients with no symptoms or in those with symptoms but lacking structural changes on radiograph. As this review is focused on studies comparing the diagnostic performance of MRI in detecting OA with other standards of reference, the studies included do not address the question of an expanded differential diagnosis nor creating subcategories of OA. Reichenbach et al. assess bone attrition on radiograph13 which could be included in diagnosing pre-OA, and which has already been found to be a potential target of therapy39. However, this was only one study and not enough to draw larger conclusions from about pre-OA diagnosis.

An important step in developing disease-modifying treatments is to create clear and validated classification criteria for the diagnosis of a pre-OA state. Pre-OA is defined as the state before clinical symptoms, or conventional radiologic markers of OA appear, but in a patient who will progress to fully developed OA. Clearly such a state cannot be defined with current diagnostic definitions of OA, but can only be detected with newer markers, radiologic, histologic, or otherwise. Possible evidence of this state has already been found histologically.40 Detection of pre-OA could be demonstrated by a prognostic study looking at various clinical and imaging features at baseline and following them longitudinally to ascertain if disease occurs. These markers, which may or may not seem useful currently, could then be measured for diagnostic usefulness against a clinical endpoint years later, such as total knee arthroplasty. Those markers which demonstrate better predictive validity could potentiate a new, MRI-based definition of pre-OA in the future. The capability to designate patients as pre-OA and likewise to follow pre-OA disease activity, would allow testing of disease modifying therapies in this earlier, and hopefully more easily-altered, stage of the disease.

This analysis found that MRI has some potential as a non-invasive method of visualizing OA when compared with standard radiograph, histology, gross dissection and other techniques. Based on currently described MRI features of OA, MRI has more utility in ruling out OA when otherwise suspected, than in detecting new OA. However, with an overall sensitivity below that of clinical and radiographic diagnosis and with these more cost-effective diagnostic tools currently used in the clinic there would seem to be no indication for using MRI in routine clinical diagnosis at this time. Given the current lack of disease-modifying therapeutic options available for treating OA and the lack of validated classification criteria for diagnosing early OA, MRI should not be used in a clinical setting for diagnosis of OA.

Acknowledgements

We recognize the invaluable support of Valorie Thompson for administrative and editorial support and OARSI for their invaluable support of this activity. We would also like to recognize the invaluable support of Kelly Hirko and Leo Menashe who assisted with the systematic review. David Hunter receives research support from Australian Research Council. Weiya Zhang receives research support from The Arthritis Research UK, The BUPA Foundation, EULAR, OARSI, Savient.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Other authors declared no conflict of interest.

Contributions DJH conceived and designed the study, drafted the manuscript and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to finished article. EL and WZ were also involved in the design of the study. All authors contributed to acquisition of the data. All authors critically revised the manuscript and gave final approval of the article for submission.

References

- 1.Heinegard D, Saxne T. The role of the cartilage matrix in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(1):50–6. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guccione AA, Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Anthony JM, Zhang Y, Wilson PW, et al. The effects of specific medical conditions on the functional limitations of elders in the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(3):351–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiphof D, Boers M, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Differences in descriptions of Kellgren and Lawrence grades of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(7):1034–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.079020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–49. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang W, Doherty M, Peat G, Bierma-Zeinstra MA, Arden NK, Bresnihan B, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(3):483–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.113100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. http://www3.aaos.org/education/anmeet/anmt2008/poster/poster.cfm?Pevent=P145.

- 7.Li KC, Higgs J, Aisen AM, Buckwalter KA, Martel W, McCune WJ. MRI in osteoarthritis of the hip: gradations of severity. Magn Reson Imaging. 1988;6(3):229–36. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(88)90396-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter DJ, Zhang YQ, Tu X, Lavalley M, Niu JB, Amin S, et al. Change in joint space width: hyaline articular cartilage loss or alteration in meniscus? Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(8):2488–95. doi: 10.1002/art.22016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madan-Sharma R, Watt I, Bloem JL, Kruijsen MW, Marijnissen AC, Meulenbelt I, et al. Characteristics at magnetic resonance imaging of knees of a healthy population compared to knees with early osteoarthritis-related complaints: the CHECK cohort. RSNA. 2009 LL-MK2083-R02. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter D, Arden N, Conaghan PG, Eckstein F, Gold G, Grainger A, et al. Definition of osteoarthritis on MRI: results of a Delphi exercise. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2011.04.017. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2011.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckstein F, Burstein D, Link TM. Quantitative MRI of cartilage and bone: degenerative changes in osteoarthritis. NMR Biomed. 2006;19(7):822–54. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amin S, LaValley MP, Guermazi A, Grigoryan M, Hunter DJ, Clancy M, et al. The relationship between cartilage loss on magnetic resonance imaging and radiographic progression in men and women with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(10):3152–9. doi: 10.1002/art.21296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reichenbach S, Guermazi A, Niu J, Neogi T, Hunter DJ, Roemer FW, et al. Prevalence of bone attrition on knee radiographs and MRI in a community-based cohort. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(9):1005–10. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143(1):29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodler J, Haghighi P, Pathria MN, Trudell D, Resnick D. Meniscal changes in the elderly: correlation of MR imaging and histologic findings. Radiology. 1992;184(1):221–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.184.1.1609084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Recht MP, Kramer J, Marcelis S, Pathria MN, Trudell D, Haghighi P, et al. Abnormalities of articular cartilage in the knee: analysis of available MR techniques. Radiology. 1993;187(2):473–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.2.8475293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Disler DG, McCauley TR, Kelman CG, Fuchs MD, Ratner LM, Wirth CR, et al. Fat-suppressed three-dimensional spoiled gradient-echo MR imaging of hyaline cartilage defects in the knee: comparison with standard MR imaging and arthroscopy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(1):127–32. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.1.8659356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leunig M, Werlen S, Ungersbock A, Ito K, Ganz R. Evaluation of the acetabular labrum by MR arthrography. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(2):230–4. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b2.7288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boegard T. Radiography and bone scintigraphy in osteoarthritis of the knee--comparison with MR imaging. Acta Radiol Suppl. 1998;418:7–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawahara Y, Uetani M, Nakahara N, Doiguchi Y, Nishiguchi M, Futagawa S, et al. Fast spin-echo MR of the articular cartilage in the osteoarthrotic knee. Correlation of MR and arthroscopic findings. Acta Radiol. 1998;39(2):120–5. doi: 10.1080/02841859809172164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trattnig S, Huber M, Breitenseher MJ, Trnka HJ, Rand T, Kaider A, et al. Imaging articular cartilage defects with 3D fat-suppressed echo planar imaging: comparison with conventional 3D fat-suppressed gradient echo sequence and correlation with histology. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22(1):8–14. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uhl M, Allmann KH, Tauer U, Laubenberger J, Adler CP, Ihling C, et al. Comparison of MR sequences in quantifying in vitro cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis of the knee. Br J Radiol. 1998;71(843):291–6. doi: 10.1259/bjr.71.843.9616238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bachmann GF, Basad E, Rauber K, Damian MS, Rau WS. Degenerative joint disease on MRI and physical activity: a clinical study of the knee joint in 320 patients. Eur Radiol. 1999;9(1):145–52. doi: 10.1007/s003300050646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plotz GM, Brossmann J, Schunke M, Heller M, Kurz B, Hassenpflug J. Magnetic resonance arthrography of the acetabular labrum. Macroscopic and histological correlation in 20 cadavers. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(3):426–32. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b3.10215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshioka H, Stevens K, Hargreaves BA, Steines D, Genovese M, Dillingham MF, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of articular cartilage of the knee: comparison between fat-suppressed three-dimensional SPGR imaging, fat-suppressed FSE imaging, and fat-suppressed three-dimensional DEFT imaging, and correlation with arthroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;20(5):857–64. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishii T, Tanaka H, Nakanishi K, Sugano N, Miki H, Yoshikawa H. Fat-suppressed 3D spoiled gradient-echo MRI and MDCT arthrography of articular cartilage in patients with hip dysplasia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185(2):379–85. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.2.01850379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruyere O, Genant H, Kothari M, Zaim S, White D, Peterfy C, et al. Longitudinal study of magnetic resonance imaging and standard X-rays to assess disease progression in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(1):98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mutimer J, Green J, Field J. Comparison of MRI and wrist arthroscopy for assessment of wrist cartilage. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2008;33(3):380–2. doi: 10.1177/1753193408090395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oda H, Igarashi M, Sase H, Sase T, Yamamoto S. Bone bruise in magnetic resonance imaging strongly correlates with the production of joint effusion and with knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13(1):7–15. doi: 10.1007/s00776-007-1195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saadat E, Jobke B, Chu B, Lu Y, Cheng J, Li X, et al. Diagnostic performance of in vivo 3-T MRI for articular cartilage abnormalities in human osteoarthritic knees using histology as standard of reference. Eur Radiol. 2008;18(10):2292–302. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0989-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kijowski R, Blankenbaker DG, Davis KW, Shinki K, Kaplan LD, De Smet AA. Comparison of 1.5− and 3.0-T MR imaging for evaluating the articular cartilage of the knee joint. Radiology. 2009;250(3):839–48. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2503080822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li W, Du H, Scheidegger R, Wu Y, Prasad PV. Value of precontrast T(1) for dGEMRIC of native articular cartilage. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29(2):494–7. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Diagnostic tests 4: likelihood ratios. BMJ. 2004;329(7458):168–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7458.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. http://healthcarebluebook.com/page_Results.aspx?SearchTerms=knee+radiograph.

- 38. http://newchoicehealth.com/Directory/Procedure/106/Knee%20X-Ray.

- 39.Carbone LD, Nevitt MC, Wildy K, Barrow KD, Harris F, Felson D, et al. The relationship of antiresorptive drug use to structural findings and symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(11):3516–25. doi: 10.1002/art.20627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thambyah A, Broom N. On new bone formation in the pre-osteoarthritic joint. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2009;17(4):456–63. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]