Abstract

Background

Advertisement of fast food on TV may contribute to youth obesity.

Purpose

The goal of the study was to use cued recall to determine whether TV fast-food advertising is associated with youth obesity.

Methods

A national sample of 2541 U.S. youth, aged 15–23 years, were surveyed in 2010–2011; data were analyzed in 2012. Respondents viewed a random subset of 20 advertisement frames (with brand names removed) selected from national TV fast-food restaurant advertisements (n=535) aired in the previous year. Respondents were asked if they had seen the advertisement, if they liked it, and if they could name the brand. A TV fast-food advertising receptivity score (a measure of exposure and response) was assigned; a 1-point increase was equivalent to affirmative responses to all three queries for two separate advertisements. Adjusted odds of obesity (based on self-reported height and weight), given higher TV fast-food advertising receptivity, are reported.

Results

The prevalence of overweight and obesity, weighted to the U.S. population, was 20% and 16%, respectively. Obesity, sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, fast-food restaurant visit frequency, weekday TV time, and TV alcohol advertising receptivity were associated with higher TV fast-food advertising receptivity (median=3.3 [interquartile range: 2.2–4.2]). Only household income, TV time, and TV fast-food advertising receptivity retained multivariate associations with obesity. For every 1-point increase in TV fast-food advertising receptivity score, the odds of obesity increased by 19% (OR=1.19, 95% CI=1.01, 1.40). There was no association between receptivity to televised alcohol advertisements or fast-food restaurant visit frequency and obesity.

Conclusions

Using a cued-recall assessment, TV fast-food advertising receptivity was found to be associated with youth obesity.

Introduction

Exposure to marketing of calorie-dense foods is recognized as a probable risk factor for obesity.1,2 Advertising for these foods is pervasive; a 2012 U.S. Federal Trade Commission report estimated that the food industry spent approximately $1.8 billion in food and beverage marketing to children and adolescents, and $9.7 billion in marketing to all audiences.3 Television is the most common venue, exposing adolescents to an average of 17 food advertisements per day,4 predominantly for calorie-dense fast foods, cereal, snacks, and sugar-sweetened beverages.2–8 Young people are considered an important target market for food advertising given their purchasing power and the potential to shape lifelong eating patterns and brand preferences.5, 9–11

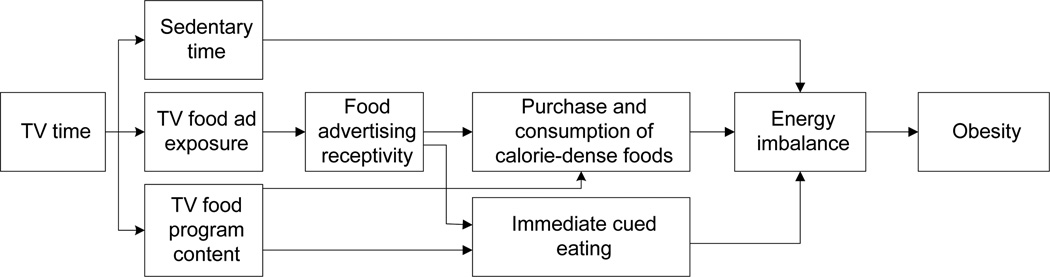

Two systematic reviews and subsequent studies have concluded that TV food advertising influences food choices, brand preferences, and consumption of calorie-dense foods.2,12–16 However, there are few studies on the association between TV food advertising and obesity itself. Time spent watching TV is an established risk factor for obesity,2,5,17,18 and exposure to food advertising on TV is one possible mediator of this TV–obesity relationship. Other possible mechanisms include sedentary time and food-related TV program content (Figure 1).5,16,18–20

Figure 1.

Theoretic model of TV food advertising receptivity and obesity

To date, few studies have disaggregated food advertising effects from other TV-related mechanisms.18,21 An association between TV advertising exposure and obesity has been demonstrated indirectly in epidemiologic studies involving younger children, estimating exposure through TV viewership and program-specific advertising.12,21 An ecologic study across countries demonstrated a link between quantity of advertising on children’s TV and obesity.22 Finally, several small experimental studies have demonstrated associations between TV food marketing and obesity in young children.23,24 However, studies in older youth are particularly limited,2 and the IOM summarized the literature by stating that there is evidence of an association between adiposity and TV advertising exposure, but that it is insufficient to convincingly support a causal relationship, and that further research is needed.2

Persuasive communication theory suggests that response to advertising messaging progresses through several stages—collectively termed marketing receptivity—prior to behavioral change: exposure to the marketing message, attention to and understanding of it, and development of a cognitive or affective response.16,25,26 Marketing receptivity has been operationalized and linked with behavior for tobacco25,27–29 and alcohol,30–35 but less consistently so for food marketing and obesity. Small experimental studies involving young children have demonstrated that ad recognition and brand awareness are associated with consumption patterns and overweight.23,24,36–39 However, in a regional survey, overweight adolescents were less likely than normal-weight adolescents to report that a favorite ad was for a food product.40 That study was not specific to food advertising because it combined food and beverage types (including alcohol). Thus, additional studies are needed to further define the association of food advertising receptivity with obesity.

To date, no studies in the U.S. have employed cued-recall methods to determine exposure and response (termed “receptivity”) to TV fast-food advertising, and to assess its association with obesity in youth. It is hypothesized that higher receptivity to fast-food advertising is associated with higher risk of obesity.

Methods

Recruitment

From Fall 2010 to Spring 2011, a total of 3342 participants aged 15–23 years were recruited from 6466 eligible U.S. households via random-digit-dial telephone survey using landline and cell phone frames. Telephone surveys were conducted by trained interviewers using a computer-assisted telephone interview system. Consent was obtained from those aged ≥18 years, and parental permission and adolescent assent was obtained for participants aged <18 years. The survey was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College.

Survey Methods

Participants completed an initial telephone survey and were then directed to a web-based survey that included image-based cued-recall questions (2541 completed both surveys). The extended interview completion rate was 56.3% for landline and 43.8% for cell phone samples (complete information about recruitment and response rates is available on request). Compared to the 2011 U.S. Current Population Survey (CPS), the unweighted survey sample was broadly similar with respect to gender, region of the country, and household income, and had fewer young adults and fewer minorities, especially blacks and hispanics (8% and 12% compared with 14% and 20% on the CPS). To improve generalizability, data were weighted to reflect prevalence and associations for the U.S. population in this age range.

Measures

Outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was BMI and BMI percentile (for adolescents), calculated from self-reported height and weight using CDC definitions.41 For adolescents, BMI percentile was categorized as obese (BMI ≥95th percentile); overweight (BMI 85th to <95th percentile); normal/underweight (0 to <85th percentile). For subjects aged ≥20 years, CDC cutoffs of BMI ≥25 and <30 were termed overweight, and ≥30 obese (www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi). Quality-assurance checks used by the CDC and Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System were applied to data to eliminate implausible height, weight, and BMI values (with participants ≥240 months set at 240 months for this determination). Weights that corresponded with the 2000 CDC weight-for-age z-scores that were < −5 or >5; height-for-age z-scores < −5 and >4; and BMI-for-age z-scores that were < −4 or >5 were eliminated as biologically implausible values.42,43

Exposure measures

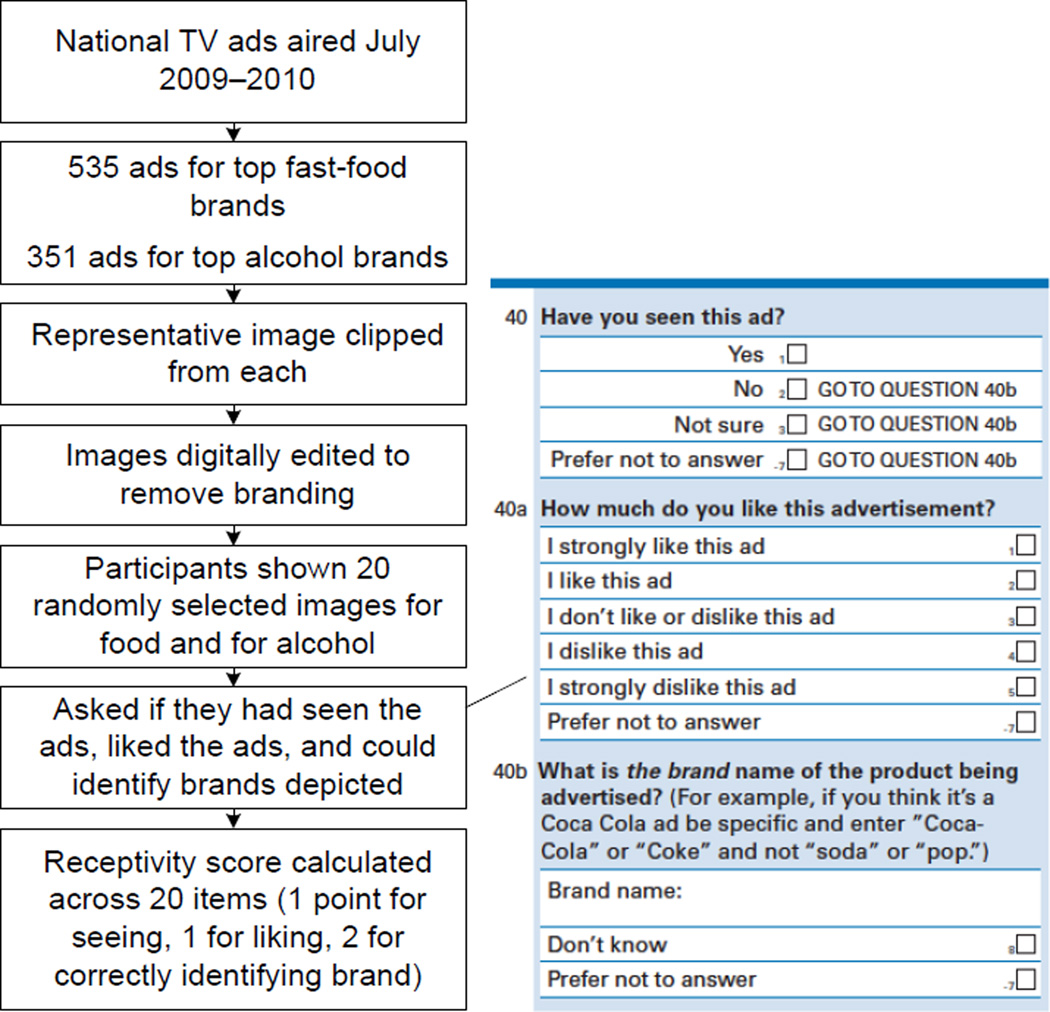

Drawing on previous studies,28,29,32,33 a cued-recall assessment of youth TV fast-food advertising receptivity (TV-FFAR) was developed that employed fast-food advertising images (Figure 2). The sample frame consisted of all fast-food restaurant ads that aired on national TV in the year prior to the survey, purchased from a marketing surveillance company (www.kantarmedia.com). This broad selection of ads was used in order to assess penetration of all TV advertising into the target population irrespective of the intended demographic market.

Figure 2.

Cued-recall methods

Of the 535 unique ads for 20 top fast-food restaurants (determined from 2010 QSR Magazine: www.qsrmagazine.com/reports/2010-qsr-50), a representative still image was chosen and digitally edited to remove branding. Subjects were shown 20 randomly selected images, and a TV-FFAR score computed with 1 point if they reported having seen an ad (recognition); 1 point if they liked it (affective response, asked only of those reporting having seen the ad); and 2 points if they could correctly identify the brand (cued recall) for a total possible score of 80 points over 20 ads. Greater weight was given for the cued-recall response, because it requires both recognition and decoding to identify the advertised brand.

Cognitive psychology research has found that compared with free recall (e.g., have you seen TV food advertising?), recognition (e.g., have you seen the ad in the picture?) and cued recall (e.g., can you name the brand depicted?) are better at triggering memory retrieval.44 Visual cues quickly lead to a judgment of whether something is familiar and facilitate recall, in contrast to free recall, which requires a number of executive functions to retrieve and summarize information from long-term memory.44 A similar methodology using recognition and cued recall of masked tobacco and alcohol ads was used to link advertising to substance use among German youth.28,29,32,33

For ease of interpretation in multivariate analysis, scores were divided by 8 (the equivalent of recognition, liking, and cued recall of two ads) and trimmed to the 99th percentile to eliminate outlier effects. In order to test the specificity of the association between TV-FFAR and obesity, alcohol advertising receptivity was assessed as a second health-risk behavior, not hypothesized to be linked with youth obesity, through cued response to images from 351 unique beer and distilled spirits ads that had also aired nationally over the previous year.45

Hypothesized Causal Pathways

Before fitting the multivariate model, possible causal pathways were considered to distinguish mediators from covariates. In addition to illustrating pathways from TV time to obesity, Figure 1 illustrates the current interpretation, based on the literature, of how TV marketing exposure may be associated with obesity. Exposure to advertising while watching TV could prompt a response to that ad, and influence immediate cued eating as well as future purchase and consumption of calorie-dense branded foods, contributing to energy imbalance. Thus, greater consumption of fast food12,46–51; sugar-sweetened beverages52,53; and/or snacks18,19 is a possible mediator of the relationship between TV advertising exposure and obesity.2,54

Covariates

Sociodemographic covariates included race/ethnicity,55 household income, and highest level of education (assessed of parent for participants aged <18 years, and directly otherwise). Age and gender were assessed but not included in regression analyses because the dependent variable was based on age- and gender-adjusted BMI z-score. Physical activity was assessed by asking: During the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 minutes per day?56

As in previous studies,46–48,57 fast-food restaurant visit frequency was assessed by asking, for 20 top fast-food restaurants: In the past 30 days, how many times did you buy food or drink from each of these restaurants? (free response for each restaurant listed). Scores were summed to provide a total monthly fast-food visit count, which was trimmed to the 99th percentile to minimize outlier influence. TV time was assessed by asking: On week days, how many hours a day do you usually watch television programs or movies either on TV or over the Internet? (none, <1 hr, 1–2 hrs, 3–4 hrs, >=4 hrs). Snacking while watching TV was assessed with: How often do you snack when you are watching television programs or movies either on TV or over the internet (never, rarely, sometimes, usually, always)?18

Finally, sugar-sweetened beverage consumption was assessed using two survey items: During the past 7 days, how many times did you drink a can, bottle, or glass of soda or pop, such as Coke, Pepsi, or Sprite? Do not include diet soda or diet pop56; and During the past 7 days, how many times did you drink punch, Kool-Aid, sports drinks, or other fruit-flavored drinks? Do not count 100% juice, soda or energy drinks (for both: none, 1–3/week, 4–6/week, 1/day, 2/day 3/day, >=4/day).

Data Analysis

Analyses, completed in 2012, were weighted to reflect characteristics of the U.S. population. Descriptive statistics included weighted proportions and means. Bivariate associations between continuous TV-FFAR and obesity were visualized using a lowess curve, and bivariate associations were assessed with F-tests. Simple and multiple weighted logistic regressions were used to model the relationships between dichotomous obesity TV-FFAR and other variables. All analyses were completed using SAS 9.3. Variances were estimated using Jackknife replicate weights.

Results

Description of the Sample

Participants were aged 15–23 years and were equally divided by gender. Weighted percentages for predictor variables are shown in Table 1. Some 58% were white, 15% black, 19% Hispanic, and 8% mixed/other race. Household annual income was ≥$50,000 in 53% of respondents; 84% reported a high school degree or higher. Some 16% of subjects were obese and 20% overweight. With respect to potential risk factors for obesity, 35% reported infrequent/no exercise; 33% soda and 18% other sugar-sweetened beverage consumption ≥4 days/week; 23% sometimes/always snacking while viewing TV; and 46% watching ≥3 hours TV daily. Median number of visits to fast-food restaurants queried was 11 times per month (IQR 3.3–13.7). Median alcohol advertising receptivity score was 1.7 (IQR 0.7–2.4, range 0–5.1) and median TV-FFAR score was 3.3 (IQR 2.2–4.2, range 0.1–6.5)—the equivalent, for example, of seeing, liking, and correctly identifying 6 or 7 of 20 ads.

Table 1.

Sample Description and Bivariate Association with TV Fast-food Advertising Receptivity

| Variables | Weighted % or median (Q1–Q3) |

M (SE) or correlation coefficient with Fast-food Ad Receptivity |

Test of trend: p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.74 | ||

| 15–17 | 35.1 | 3.3 (0.07) | |

| 18–20 | 32.8 | 3.3 (0.09) | |

| 21–23 | 32.1 | 3.4 (0.10) | |

| Gender | 0.43 | ||

| Male | 51.1 | 3.3 (0.06) | |

| Female | 48.9 | 3.2 (0.06) | |

| Race | 0.049 | ||

| White | 58.2 | 3.2 (0.04) | |

| Black | 14.5 | 3.6 (0.15) | |

| Hispanic | 18.9 | 3.2 (0.14) | |

| Mixed / Other | 8.3 | 3.0 (0.12) | |

| Household Annual Income, $ | 0.74 | ||

| <20,000 | 17.6 | 3.2 (0.14) | |

| 20,000–30,000 | 10.5 | 3.4 (0.12) | |

| 30,000–50,000 | 18.9 | 3.3 (0.12) | |

| 50,000–75,000 | 16.7 | 3.4 (0.11) | |

| 75,000–100,000 | 13.0 | 3.4 (0.10) | |

| >100,000 | 23.4 | 3.2 (0.08) | |

| Education Level | 0.002 | ||

| < High school | 15.7 | 3.2 (0.13) | |

| High school | 19.5 | 3.0 (0.10) | |

| Some post–high school | 35.9 | 3.3 (0.07) | |

| Associates/Bachelors | 19.9 | 3.5 (0.09) | |

| >Bachelors | 8.9 | 3.1 (0.12) | |

| Weight Category | 0.001 | ||

| Obese | 16.0 | 3.6 (0.10) | |

| Overweight | 20.2 | 3.3 (0.10) | |

| Normal weight | 63.8 | 3.2 (0.05) | |

| Exercise – days of 60 minutes total, in past week |

0.16 | ||

| 0–2 | 35.3 | 3.2 (0.08) | |

| 3–5 | 36.9 | 3.4 (0.07) | |

| 6 or 7 | 27.8 | 3.2 (0.07) | |

| Soda, in past 7 days | 0.18 | ||

| 0 | 30.5 | 3.1 (0.08) | |

| 1–3 | 37.0 | 3.4 (0.07) | |

| 4–7 | 19.6 | 3.3 (0.12) | |

| ≥2 per day | 13.0 | 3.3 (0.12) | |

| Other Sugar-sweetened Beverages, in past 7 days |

<0.001 | ||

| 0 | 44.0 | 3.0 (0.06) | |

| 1–3 | 29.7 | 3.4 (0.06) | |

| 4–7 | 10.1 | 3.5 (0.13) | |

| ≥2 per day | 8.2 | 3.7 (0.17) | |

| Snacking During TV | 0.26 | ||

| Never/rarely | 76.8 | 3.3 (0.05) | |

| Sometimes | 17.1 | 3.4 (0.10) | |

| Usually/always | 6.1 | 3.6 (0.18) | |

| TV Time (hours per day on weekdays) | <0.001 | ||

| <1 | 15.0 | 2.7 (0.10) | |

| 1–2 | 38.8 | 3.2 (0.06) | |

| ≥3 | 46.2 | 3.5 (0.06) | |

| Fast-food Restaurant visit Frequency | 10.9 (3.3–13.7) | 0.2 | <0.001 |

| TV Fast-food Advertising Receptivity | 3.3 (2.2–4.2) | 1 | - |

| TV Alcohol Advertising Receptivity | 1.7 (0.7–2.4) | 0.5 | <0.001 |

Note: Boldface indicates significance.

Bivariate Association Between Covariates and Receptivity

Table 1 (Column 2) describes bivariate associations between independent variables and TV-FFAR. With respect to categoric variables, mean TV-FFAR scores were associated with higher education, other sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, TV time, and obesity. For continuous variables, correlations were found between TV-FFAR and both fast-food visit frequency (0.2, p<0.001) and alcohol advertising receptivity (0.5, p<0.001).

Bivariate Association Between Receptivity and Obesity

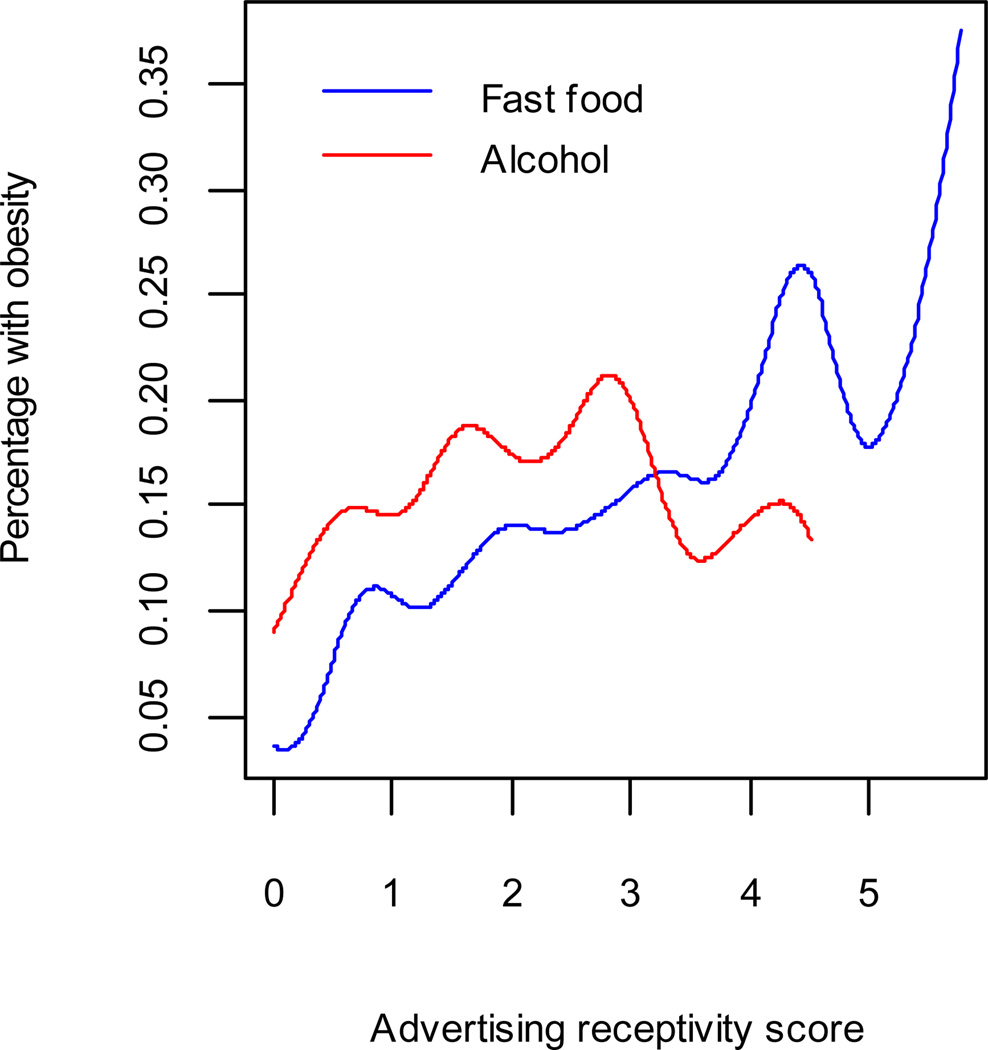

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between both fast-food and alcohol advertising receptivity, and obesity. The curves illustrate the linear relationship. Less than 10% of respondents with a low TV-FFAR score (≤1) were obese, whereas >15%–20% with a high TV-FFAR score (≥5) were obese. There was also a weak but significant upward trend for the relationship between alcohol advertising receptivity and obesity. Other variables with a bivariate association with obesity (Table 2) included education, household income, black race, and TV time. Although TV-FFAR was associated with greater fast-food restaurant frequency, fast-food frequency was not significantly associated with obesity.

Figure 3.

Unadjusted association between advertising receptivity and obesity

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Association with Obesity

| OR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Partly Adjusted | Adjusted | |

| Fast-food Advertising Receptivity | 1.23 (1.11, 1.36) | 1.21 (1.05, 1.39) | 1.19 (1.01, 1.40) |

| Alcohol Advertising Receptivity | 1.12 (1.01, 1.25) | 1.06 (0.91, 1.24) | 1.08 (0.91, 1.28) |

| Education | 0.80 (0.66, 0.96) | 0.87 (0.71, 1.06) | 0.90 (0.72, 1.12) |

| Household Annual Income | 0.81 (0.73, 0.89) | 0.85 (0.76, 0.95) | 0.84 (0.75, 0.94) |

| Race | |||

| White | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Black | 1.76 (1.01, 3.06) | 1.54 (0.80, 2.98) | 1.78 (0.85, 3.75) |

| Hispanic | 1.32 (0.70, 2.49) | 1.37 (0.72, 2.59) | 1.12 (0.53, 2.37) |

| Mixed/Other | 0.95 (0.55, 1.65) | 1.18 (0.65, 2.15) | 1.31 (0.69, 2.49) |

| Exercise | 0.96 (0.76, 1.21) | 0.94 (0.74, 1.20) | 0.93 (0.72, 1.21) |

| Food | |||

| Soda | 1.07 (0.87, 1.30) | — | 0.97 (0.78, 1.20) |

| Other Sugar-sweetened Beverages | 1.07 (0.85, 1.36) | — | 0.89 (0.67, 1.18) |

| Snacking During TV | 0.90 (0.59, 1.38) | — | 0.79 (0.49, 1.27) |

| Fast-food Restaurant visit | |||

| Frequency | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | — | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) |

| TV time, hours | |||

| <1 | 1.00 (ref) | — | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1–2 | 1.74 (0.99, 3.05) | — | 1.70 (0.81, 3.59) |

| ≥3 | 3.82 (2.13, 6.83) | — | 2.90 (1.32, 6.37) |

Note: Boldface indicates significance.

Multivariate Associations Between Receptivity and Obesity

In a multivariate regression (Table 2, Column 2), including sociodemographic covariates and alcohol advertising receptivity but not potential mediators, the odds of obesity increased by 1.21 (95% CI=1.05, 1.39) for every 1-point increase in TV-FFAR score (equal, for example, to seeing–liking–recognizing two ads). Young people with higher household income were less likely to be obese (OR 0.85, 95% CI=0.76, 0.95). Other covariates were not significantly associated with obesity.

In a fully adjusted model (Table 2, Column 3), TV-FFAR retained an independent association with obesity (AOR 1.19, 95% CI=1.01, 1.40), even after controlling for potential mediators such as soda and other sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, TV snacking, TV time, and fast-food restaurant visit frequency. Of these, only TV time was significantly associated with obesity (AOR 2.9, 95% CI=1.32, 6.37 for highest vs lowest level); net TV-FFAR; or other covariates.

Discussion

This study assessed youth receptivity to TV food advertising and found a direct association with obesity in this sample of U.S. adolescents and young adults. The association was independent of TV alcohol advertising receptivity, suggesting that the finding is specific to food messaging. The association was also independent of TV time, suggesting that it is not simply a marker of increased sedentary time. These results are similar to other cued-recall studies on alcohol and tobacco use28,29,32,33,58 and supported by communication theory which hypothesizes that youth are exposed to advertising, become aware of it, and then develop a cognitive response that influences behavioral choices,16,25,26 such as consumption of calorie-dense foods. This work begins to address concerns that prevented the IOM from acknowledging a causal relationship between food marketing and adiposity.

The present study was designed primarily to examine the association between alcohol advertising and drinking, precluding extensive assessments of diet and activity such as validated diet recall questionnaires. However, a 20-item measure of fast-food restaurant visit frequency was included, and was related to TV-FFAR but not to obesity. This suggests that the relationship between TV-FFAR and obesity may be mediated by something other than just fast-food restaurant visit frequency, perhaps by the foods that receptive people choose to eat at these establishments.

The fact that TV-FFAR was related to higher consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages suggests that the link between TV-FFAR and obesity could also be mediated by broader food consumption patterns. In this “spill-over effect,” described by Buijzen et al.,16 advertising receptivity leads to not only brand preference, or brand switching, but also the consumption of a similar array of calorie-dense branded products and increased overall intake.13,14,36 Thus, TV-FFAR could be capturing receptivity to multiple calorie-dense foods and sweetened beverages advertised on TV, as well as an individual’s propensity to choose those foods in a variety of situations. Coon et al. expand this concept, suggesting that TV advertising may shape not only individual food choices but also broader cultural eating patterns, such as reliance on pre-prepared meals.59

Another possible mechanism that warrants further exploration is whether some individuals are more sensitive to food ads as immediate cues to action. A recent study found that individual differences in human reward-related brain activity in the nucleus accumbens in response to food images was predictive of subsequent weight gain, suggesting that heightened reward responsiveness to food cues is associated with overeating.60 In another study, obese children viewing food logos showed less activation in areas of the brain involved in cognitive control, also suggesting innate marketing vulnerability.61 These studies support correlational work that links overweight status and responsiveness to food marketing,21,36,37 as well as work demonstrating that associations between TV viewing and snacking varied among individuals based on their psychological response to eating.19 Taken in this context, TV-FFAR may identify individuals with higher responsiveness to marketing images, which could prompt snacking while viewing TV, and purchases at food outlets in response to point-of purchase marketing. The limited measure of cued eating (snacking during TV viewing) may not have been sensitive enough to capture this mediational process.

Limitations

This study was limited in its cross-sectional design, and so the directionality of the relationship between marketing recall and obesity cannot be determined—youth who are exposed to and receptive to fast-food marketing may be at risk for obesity, and yet it is possible that obese youth more frequently consume fast food, have greater brand familiarity and are thus more adept at identifying branded marketing. In addition, receptivity to food ads likely reflects exposure to cross-platform marketing campaigns that utilize digital venues in addition to TV to promote their products. Further studies are needed to assess the increasingly complex landscape of new media marketing.

The study was also limited by a narrow measure of fast-food consumption that assessed visit frequency but not food choices, and by limited measures of food consumption. As with any observational study, an unmeasured confounder could explain the relationship that was found between TV-FFAR and obesity. Finally, BMI was calculated using self-reported height and weight and may be subject to reporting bias. The study limitations, which preclude offering a mechanism whereby fast-food advertising might lead to obesity, should prompt further research in this area. The use of longitudinal designs, validated instruments for assessing diet and activity, and directly measured obesity will be necessary to explicate the possible causal pathways between food marketing and obesity (Figure 1).

Conclusion

This study adapts a novel cued-recall method to measure receptivity to fast-food TV advertisements in a national U.S. sample of adolescents and young adults. The finding of an independent relationship between higher TV fast-food advertising receptivity and obesity raises concerns about the role such advertising may play in risk of obesity.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health (AA015591 & CA077026; JDS and 1K23AA021154 – 01A1; ACM) and SYNERGY Scholars Award from the Dartmouth Center for Clinical and Translational Science (ACM).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Cairns G, Angus K, Hastings G, Caraher M. Systematic reviews of the evidence on the nature, extent and effects of food marketing to children. A retrospective summary. Appetite. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGinnis JM, Gootman JA, Kraak VI. Food marketing to children and youth: threat or opportunity? committee on food marketing the diets of children youth. National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leibowitz J, Rosch JT, Ramirez E, Brill J, Ohlhausen M. A Review of Food Marketing to Children and Adolescents: Follow-Up Report. Washington, DC: Federal Trade Commission; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gantz W, Schwartz N, Angelini J, Rideout V. Food for thought. television food advertising to children in the U.S Menlo Park. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulos R, Kuross Vikre E, Oppenheimer S, Chang H, Kanarek R. ObesiTV: How television is influencing the obesity epidemic. Physiology & Behavior. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell LM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ. Adolescent exposure to food advertising on television. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4Supplement 1):S251–S256. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell LM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ, Braunschweig CL. Nutritional content of television food advertisements seen by children and adolescents in the U.S. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):576–583. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stitt C, Kunkel D. Food advertising during children's television programming on broadcast and cable channels. Health Communication. 2008;23(6):573–584. doi: 10.1080/10410230802465258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris JL, Pomeranz JL, Lobstein T, Brownell KD. A crisis in the marketplace: how food marketing contributes to childhood obesity and what can be done. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009:211–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyland EJ, Halford JC. Television advertising and branding: Effects on eating behaviour and food preferences in children. Appetite. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Story M, French S. Food advertising and marketing directed at children and adolescents in the U.S. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2004;1(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreyeva T, Kelly IR, Harris JL. Exposure to food advertising on television: associations with children's fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Econ Human Biology. 2011;9(3):221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scully M, Dixon H, Wakefield M. Association between commercial television exposure and fast-food consumption among adults. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(1):105–110. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scully M, Wakefield M, Niven P, et al. Association between food marketing exposure and adolescents' food choices and eating behaviors. Appetite. 2012;58(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cairns G, Angus K, Hastings G. The extent, nature and effects of food promotion to children: a review of the evidence to December 2008. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buijzen M, Schuurman J, Bomhof E. Associations between children's television advertising exposure and their food consumption patterns: A household diary-survey study. Appetite. 2008;50(2–3):231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crespo CJ, Smit E, Troiano RP, Bartlett SJ, Macera CA, Andersen RE. Television watching energy intake, obesity in U.S. children: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(3):360–365. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cleland VJ, Schmidt MD, Dwyer T, Venn AJ. Television viewing and abdominal obesity in young adults: is the association mediated by food and beverage consumption during viewing time or reduced leisure-time physical activity? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1148–1155. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snoek HM, van Strien T, Janssens JM, Engels RC. The effect of television viewing on adolescents' snacking: individual differences explained by external, restrained and emotional eating. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(3):448–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris JL, Bargh JA, Brownell KD. Priming effects of television food advertising on eating behavior. Health Psychol. 2009;28(4):404–413. doi: 10.1037/a0014399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmerman FJ, Bell JF. Associations of television content type and obesity in children. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):334–340. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lobstein T, Dibb S. Evidence of a possible link between obesogenic food advertising and child overweight. Obesity Rev. 2005;6(3):203–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halford JC, Boyland EJ, Hughes GM, Stacey L, McKean S, Dovey TM. Beyond-brand effect of television food advertisements on food choice in children: the effects of weight status. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(9):897–904. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007001231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halford JCG, Gillespie J, Brown V, Pontin EE, Dovey TM. Effect of television advertisements for foods on food consumption in children. Appetite. 2004;42(2):221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Berry CC. Tobacco industry promotion of cigarettes and adolescent smoking. JAMA. 1998;279(7):511–515. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.7.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGuire WJ. Attitudes and attitude change. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E, editors. Handbook of social psychology. 3rd ed. New York: Random House; 1985. pp. 233–346. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilpin EA, White MM, Messer K, Pierce JP. Receptivity to tobacco advertising and promotions among young adolescents as a predictor of established smoking in young adulthood. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1489–1495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.070359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanewinkel R, Isensee B, Sargent JD, Morgenstern M. Cigarette advertising and teen smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):e271–e278. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanewinkel R, Isensee B, Sargent JD, Morgenstern M. Cigarette advertising and adolescent smoking. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McClure AC, Stoolmiller M, Tanski SE, Worth KA, Sargent JD. Alcohol-branded merchandise and its association with drinking attitudes and outcomes in U.S. adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(3):211–217. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClure AC, Stoolmiller M, Tanski SE, Engels RC, Sargent JD. Alcohol marketing receptivity, marketing specific cognitions, and underage binge drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012 Dec 19; doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01932.x. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgenstern M, Isensee B, Sargent JD, Hanewinkel R. Attitudes as mediators of the longitudinal association between alcohol advertising and youth drinking. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(7):610–616. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgenstern M, Isensee B, Sargent JD, Hanewinkel R. Exposure to alcohol advertising and teen drinking. Prev Med. 2011;52(2):146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClure AC, Dal Cin S, Gibson J, Sargent JD. Ownership of alcohol-branded merchandise and initiation of teen drinking. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(4):277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henriksen L, Feighery EC, Schleicher NC, Fortmann SP. Receptivity to alcohol marketing predicts initiation of alcohol use. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(1):28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halford JCG, Boyland EJ, Hughes G, Oliveira LP, Dovey TM. Beyond-brand effect of television (TV) food advertisements/commercials on caloric intake and food choice of 5–7-year-old children. Appetite. 2007;49(1):263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forman J, Halford JC, Summe H, MacDougall M, Keller KL. Food branding influences ad libitum intake differently in children depending on weight status Results of a pilot study. Appetite. 2009;53(1):76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keller KL, et al. The impact of food branding on children's eating behavior and obesity. Physiol Behav. 2012;106:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arredondo E, Castaneda D, Elder J, Slymen D, Dozier D. Brand name logo recognition of fast food and healthy food among children. J Commun Health. 2009;34(1):73–78. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adachi-Mejia AM, Sutherland LA, Longacre MR, et al. Adolescent weight status and receptivity to food TV advertisements. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43(6):441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the U.S.: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11. 2002;246:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.CDC. Pediatric Nutrition Surveillance System (PedNSS) www.cdc.gov/pednss/pop-ups/biv_pednss.htm.

- 43.CDC. Biologically Implausible Value Documentation. www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/growthcharts/resources/BIV-cutoffs.pdf.

- 44.Eichenbaum H. Learning & Memory. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.The Beverage Information Group. Handbook Advance. 2009:124. pages 20,92,124. p. 20,92. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duffey KJ, Gordon-Larsen P, Jacobs DR, Jr., Williams OD, Popkin BM. Differential associations of fast food and restaurant food consumption with 3-y change in body mass index: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(1):201–208. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, et al. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. 2005;365(9453):36–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Powell LM, Nguyen BT. Fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption among children and adolescents: effect on energy, beverage, and nutrient intake. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012:1–7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bowman SA, Gortmaker SL, Ebbeling CB, Pereira MA, Ludwig DS. Effects of fast-food consumption on energy intake and diet quality among children in a national household survey. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1 Pt 1):112–118. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(12):1823–1833. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer D, Laska MN, Story M. Young adults and eating away from home: associations with dietary intake patterns and weight status differ by choice of restaurant. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(11):1696–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ludwig DS, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SL. Relation between consumption of sugar-sweetened drinks and childhood obesity: a prospective, observational analysis. Lancet. 2001;357(9255):505–508. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA. 2004;292(8):927–934. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiecha JL, Finkelstein D, Troped PJ, Fragala M, Peterson KE. School vending machine use and fast-food restaurant use are associated with sugar-sweetened beverage intake in youth. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(10):1624–1630. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jackson C, Brown JD, L'Engle KL. R-rated movies, bedroom televisions, and initiation of smoking by white and black adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(3):260–268. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.CDC. Adolescent and School Health. 2009 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. 2009 www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/questionnaire_rationale.htm Published.

- 57.Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer DR, Story MT, Wall MM, Harnack LJ, Eisenberg ME. Fast food intake: longitudinal trends during the transition to young adulthood and correlates of intake. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Unger JB, Schuster D, Zogg J, Dent CW, Stacy AW. Alcohol advertising exposure and adolescent alcohol use: A comparison of exposure measures. Addiction Res Theory. 2003;11(3):177–193. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coon KA, Goldberg J, Rogers BL, Tucker KL. Relationships between use of television during meals and children's food consumption patterns. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):E7. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Demos KE, Heatherton TF, Kelley WM. Individual differences in nucleus accumbens activity to food and sexual images predict weight gain and sexual behavior. J Neuroscience : Official J Society Neuroscience. 2012;32(16):5549–5552. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5958-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bruce AS, Lepping RJ, Bruce JM, et al. Brain responses to food logos in obese and healthy weight children. J Pediatr. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]