Abstract

The application of Conversation Analysis (CA) to the investigation of agrammatic aphasia reveals that utterances produced by speakers with agrammatism engaged in everyday conversation differ significantly from utterances produced in response to decontextualised assessment and therapy tasks. Early studies have demonstrated that speakers with agrammatism construct turns from sequences of nouns, adjectives, discourse markers and conjunctions, packaged by a distinct pattern of prosody. This article presents examples of turn construction methods deployed by three people with agrammatism as they take an extended turn, in order to recount a past event, initiate a discussion or have a disagreement. This is followed by examples of sequences occurring in the talk of two of these speakers that result in different, and more limited, turn construction opportunities, namely “test” questions asked in order to initiate a new topic of talk, despite the conversation partner knowing the answer. The contrast between extended turns and test question sequences illustrates the effect of interactional context on aphasic turn construction practices, and the potential of less than optimal sequences to mask turn construction skills. It is suggested that the interactional motivation for test question sequences in these data are to invite people with aphasia to contribute to conversation, rather than to practise saying words in an attempt to improve language skills. The idea that test question sequences may have their origins in early attempts to deal with acute aphasia, and the potential for conversation partnerships to become “stuck” in such interactional patterns after they may have outlived their usefulness, are discussed with a view to clinical implications.

Keywords: Aphasia, conversation analysis, agrammatism, turn construction, test questions

Background

At the heart of communication lies the interaction between two or more people, achieved for the most part through everyday conversation. Conversation represents the primary context for language use, and is the vehicle through which we make and maintain relationships and influence the environment. Language impairments such as aphasia strike at the heart of human identity, leading to social isolation, depression and reduced quality of life (Hilari & Byng, 2009). Each year in England and Wales, over 130 000 people have a first stroke; approximately one third has to adjust to life with the permanent and pervasive effects of aphasia. On the whole, language tests are not good predictors of performance in everyday communication because, as Audrey Holland (1980) noted over 30 years ago, people with aphasia generally communicate better than they are able to speak. The disorder of agrammatic aphasia (or agrammatism), the focus of this article, is classically characterised as a non-fluent aphasia, with associated “telegraphic” speech, word order and morphological errors and reduced ability to produce verbs, although comprehension remains relatively intact (see for example, Goodglass, Kaplan, & Barresi, 2001; Marshall, 2002). The connected speech output of people with agrammatism has for the most part been investigated by analysing data elicited via picture description and storytelling (see Prins & Bastiaanse, 2004).

Recognition of the importance of everyday conversation to the long term psychosocial welfare of people with aphasia of any type or severity (Lyon, 1992; Kagan, 1995, 1998; Parr, Duchan, & Pound, 2003) has led to an upsurge in the application of qualitative research methodologies, in an attempt to engage with more authentic and naturalistic data (see Damico, Simmons-Mackie, Oelschlaeger, Elman, & Armstrong, 1999, for a review). Conversation Analysis (CA) is one such methodology that has gained attention in aphasiology (Beeke, 2012; Damico, Oelschlaeger, & Simmons-Mackie, 1999; Goodwin, 2003; Wilkinson, 1999, 2010), as well as in other areas of communication disability (Bloch & Wilkinson, 2011; Denman & Wilkinson, 2011; Gardner & Forrester, 2010; Kelly & Beeke, 2011; Mikesell, 2009; Richards & Seedhouse, 2005). It has revealed much about how aspects of language and non-verbal behaviour are used and are adapted to achieve the goal of taking a turn at talk in everyday conversation, in the presence of aphasia.

CA is a systematic procedure for the analysis of recorded, naturally occurring talk produced in everyday human interaction. It grew out of ethnomethodology, a sociological approach originating in the 1960s, via the pioneering works of Harvey Sacks and his collaborators, Emanuel Schegloff and Gail Jefferson. The principal aim is to discover how speakers understand and respond to each other via turns at talk, and how such turns are organised into sequences of interaction. The focus is on conversation as an orderly accomplishment that is negotiated between speakers. Thus, according to Hutchby and Wooffitt (1998, p. 15), “CA seeks to uncover the organization of talk not from any exterior, God’s eye view, but from the perspective of how the participants display for one another their understanding of ‘what is going on.’” An analysis begins with actual utterances in real contexts, and is not constrained by prior theoretical assumptions; it is a bottom-up, data-driven approach. CA takes the view, from linguistics, that language is a structured system for the production of meaning, but it diverges from many branches of linguistics in that it views language primarily as a vehicle for communicative interaction, rather than as a discrete system for predication (Schegloff, 1996). Thus, CA proceeds on the assumption that phonetics, lexis, grammar and prosody are primarily shaped by their use as tools to accomplish mutual understanding in turn-by-turn interactions. The reader is directed to other texts for a detailed explication of CA methodology (Schegloff, 2007; Sidnell, 2010).

The application of CA to the investigation of agrammatic aphasia, the focus of this article, shows that utterances produced by speakers with agrammatism engaged in everyday conversation differ significantly from utterances produced in response to decontextualised assessment and therapy tasks, for the languages studied so far, namely English, German and Finnish (Beeke, Wilkinson, & Maxim, 2003a, 2003b, 2007a, 2007b; Heeschen & Schegloff, 1999, 2003; Klippi & Helasvuo, 2011; Wilkinson, 1995). Beeke and colleagues have demonstrated that conversational grammar in two English speakers with agrammatism (of differing severity) consists of utterances built from sequences of nouns, adjectives, discourse markers, and conjunctions, packaged by a distinct pattern of prosody, characterised by level intonation on each non-final word in an utterance and falling intonation on the utterance-final word. See Beeke, Wilkinson, and Maxim (2009) for a detailed discussion of this prosodic strategy, and Lind (2002) for a similar pattern in Norwegian agrammatism. A CA examination of such turns revealed a systematic pairing of structure with social action, such that different forms of utterance were used to convey distinct actions. In CA, “action” refers to the social action that an utterance is designed to do, for example, invite, comment, question, decline etc. (Schegloff, 2007). For example, Roy (a speaker with aphasia studied in Beeke et al., 2007a, 2007b), deployed the following repertoire of utterances: (1) a noun-initial turn, in which a noun was followed by a word or words that served to comment, e.g. racing, Newmarket, Epsom, anywhere, but me, Ascot no., in order to convey a new topic (akin to topic-comment structure); (2) an adjective-initial turn, in which an adjective was followed by because and a reason e.g. amazing because two years or three years, in order to offer a personal view on a current topic; and (3) a turn that combined talk and mime, designed to convey an event in the absence of a verb (e.g. see Beeke et al., 2007a; Wilkinson, Beeke, & Maxim, 2010). Each of these turn construction formats was designed to achieve a different conversational action and was shown to recur in the data; i.e. the authors found a collection of individual examples that were all constructed in the same way using the same resources. Beeke and colleagues concluded that, for some speakers, conversational turns are built using systematic methods which result in recognisable telegraphic turn formats, and the motivation for their structure is interactional.

Commonly, the turns taken in everyday conversation by people with a range of aphasia types are short. Often this is due to limitations on the language resources needed to produce a complete turn at talk, but it can also be the case that the routine behaviour of a conversation partner can place interactional limitations on the type of turn that a person with aphasia takes. In our database of agrammatic conversations, questions appear to be particularly influential in shaping the turn construction opportunities of people with aphasia, particularly questions asked despite the conversation partner already knowing the answer, so-called “test” or “know answer” questions. Such question types were first outlined in the context of formal talk in the classroom. Searle (1969) differentiates between a real question and an “exam” question, the latter signalling that the speaker wants to know if the recipient knows the answer; it is a request to display knowledge, not a request for information. McHoul (1978) highlights that judgement of the sufficiency of the answer to such a question rests solely with the questioner, the teacher in this case. In a classroom situation, this creates what McHoul (1978) calls an “utterance-triad” of question-answer-comment on the sufficiency of an answer. Schegloff (2007) reinforces the idea of a “known answer” question forming a distinctive three-part sequence type: test question-response-evaluation, with the third turn evaluation revealing the purpose of the initial question to be “answering correctly”. In common with a question posed as part of a typical adjacency pair, a test question establishes the expectation of a response that will be immediate and relevant. Schegloff (2007) points out that test questioning behaviour tends to be specific to contexts such as the classroom or an interview, and thus rare in peer interactions. Levinson (1992) notes that teachers use questions both to demand participation and to test knowledge. Schegloff (2007, p. 224) suggests that outside of these contexts, the deployment of a test question has a social consequence, such that “persons finding themselves addressed with such questions in other settings may complain (whether jokingly or seriously) of being demeaned or being ‘put-down.’” In this way test questions can constitute a threat to face.

Goffman (1955, p. 123) defines face as “the positive social value a person effectively claims for himself”. This is threatened when there is a discrepancy between a person’s internal and external image; an inability to answer a test question establishes exactly this discrepancy. Test questions appear to call into question both linguistic and cognitive competence, via demands on memory and the expression of knowledge. In classroom settings they signal an imbalance in the ownership of knowledge; the “tester’s” knowledge status is set as the standard against which the “testee’s” knowledge is measured, and the testee is in the process of acquiring that knowledge. Heritage (2012a) makes a distinction between epistemic status, whether interactants have equal or unequal access to knowledge, and epistemic stance, the way in which turn design demonstrates this access to knowledge. According to Heritage (2012a), a speaker who takes an unknowing epistemic stance, by asking a question for example, invites an interlocutor to elaborate on a topic. This brings with it the potential for expansion of an interactional sequence, because “… the … experiences … of individuals are treated as theirs to know and describe.” (Heritage, 2012a, p. 6). Such a sequence concludes when the imbalance in knowledge is equalised (Heritage, 2012b). In a situation where communication is likely to be difficult, and mutual understanding may prove vulnerable, such as in aphasia, one motivation for asking a test question may be to call upon an aphasic interlocutor to join in with conversation based on knowledge to which both have equal access.

A small number of studies have examined test questioning and similar pedagogic sequences in aphasic conversation (Aaltonen & Laakso, 2010; Bauer & Kulke, 2004; Burch, Wilkinson, & Lock, 2002; Lock, Wilkinson, & Bryan, 2001). The work of Lock et al. (2001) and Burch et al. (2002) has focused on the negative emotion and interactive pressure engendered by test questions in the everyday talk of couples at home. Burch et al. (2002), observed that test questions affect the status of a person with aphasia as a competent interactant, as a result of being put “on the spot” with the expectation of an immediate response, and the subsequent (aphasic) difficulty in answering. Thus, test questions are construed as a direct threat to face. The authors went on to demonstrate how test questions could be targeted for elimination via interaction-focused intervention, such that the wife of an English-speaking man with aphasia was trained to leave silences at points where topic change was possible, instead of launching a test question, thus enabling her husband to initiate a topic. As a result, the husband’s turn constructions increased in length and content.

According to Lock et al. (2001), a type of repair known as a “correct production sequence” sometimes goes hand in hand with a test question, in a situation where the speaker with aphasia’s answer contains “errors” (often articulatory distortions). Commonly, what follows is a series of turns designed to elicit a correct production, even though the conversation partner already knows the target (Lindsay & Wilkinson, 1999). In such sequences conversation partners may actually withhold information in order to obtain a particular response from the speaker with aphasia, even though understanding has already been achieved (Wilkinson et al., 1998).

Aaltonen and Laakso (2010) highlighted an activity in the conversations of people with aphasia, referred to as “exam halts,” which they felt had parallels with pedagogic activities such as test questioning and correct production sequences. The authors showed that during exam halts, conversations ran into trouble because a speaker with aphasia encountered a word finding difficulty and the non-aphasic conversation partner withheld a guess, despite knowing the missing word and understanding the turn in progress. This was done in order to prompt the person with aphasia to produce the word him or herself. The authors contrasted these episodes with real halts, where mutual understanding was at stake, and collaborative repair was undertaken. Aaltonen and Laakso (2010) concluded that the actions of the non-aphasic partners were driven not by the wish to expose linguistic non-competence, quite the opposite. The authors suggested that the behaviour showed a lack of acceptance by the conversation partners that the speakers with aphasia were willing to portray themselves as linguistically non-competent by not self-correcting. Thus, the conversation partners were engaging in corrective “face-work” on behalf of the speaker with aphasia.

Bauer and Kulke’s (2004) work suggests we should not assume that pedagogic activities of this type always have a negative impact in conversation. They examined the home conversations of 10 families and discovered “language exercising” – sequences predominantly focused on naming and repeating – to be relevant for three of them. However, they found that the practice lost its face-threatening potential if initiated by the person with aphasia following a speech error or a word finding problem in ongoing talk. And while the threat to face was heightened when exercising was initiated by a non-aphasic interlocutor, this appeared to be the case only when the practice was enforced in the context of an other-initiated repair sequence. When exercising was proposed and agreed on locally by both interactants, in the context of a joint activity such as completing a puzzle, for example, it appeared not to have negative interactional or emotional consequences. Bauer and Kulke (2004) concluded that didactic request-response-evaluation sequences can be a positive expression of a family’s orientation towards the restoration of linguistic skills, but can also act to facilitate equal participation of a person with aphasia in a conversation, when this would otherwise not be possible.

Although the literature reveals the impact of test questions in aphasic conversation to be variable, at heart this questioning style places interactional expectations on a person with aphasia to provide a very specific known answer, and more often than not results in turn constructions limited to a noun or a noun phrase. This is perhaps one of the hardest demands to make of a person with aphasia, given that almost all individuals, regardless of aphasia type or severity, have persistent word finding difficulties.

Aims

This article explores turn construction practices in three people with agrammatic aphasia, and aims to show the effect of two very different interactional contexts, one where extended turns are made possible, and another where turn construction is limited by a test question sequence launched by the conversation partner. The analysis of extended turns aims to show how such turns are constructed, given that the person has a type of aphasia that limits the ability to deploy grammar as a resource for shaping conversational utterances. The analysis of a test question sequence for two of the three speakers with aphasia allows for a comparison of the effects of sequential context on the deployment of linguistic and other turn construction resources. The effect of these different interactional contexts on the turn constructions of the people with aphasia, and potential interactional motivations for test questions in these data, are explored in the Discussion. Finally, the clinical implications of this work are discussed.

Data and methods

Examples used in this article have been taken from a data set of approximately 50 h of videotaped home conversations between eight speakers with agrammatic aphasia and their significant other (a dyad), collected as part of a Stroke Association-funded Conversation Therapy Project at University College London (see Beckley et al., 2013; Beeke, Maxim, Best, & Cooper, 2011). Each dyad made their own video recordings of approximately 20 min of home conversation once a week for two 8-week periods, separated by an 8-week period when they received therapy (not discussed here), during which they recorded two conversations, one after week 3 of therapy and one after week 6. This resulted in a total of 18 conversations per dyad. In an attempt to maximise ecological validity, we have not analysed the first of the 18 samples, nor the first 5 min of any subsequent sample. A first pass analysis of conversation patterns over the 8 weeks prior to therapy revealed test questions to be a feature for four of the eight dyads. One of these four dyads consented for their conversations to be available for analysis up to 1 year after the end of the project and then destroyed, and so these data are not analysed here. The other three dyads consented to long term storage of their conversations. Data from two of the three are presented here (Extracts 2–5). The third dyad is not analysed because the extended turns of the speaker with aphasia contain significant amounts of complex mime; it is beyond the scope of the article to present a thorough analysis of this turn construction device (readers are referred to Beckley et al., 2013). To set the scene for this comparison of two speakers’ turns in different contexts, a single example of an extended turn by a speaker with agrammatic aphasia is presented first (Extract 1). Transcription followed common CA conventions (Jefferson, 1984). All names used to refer to the dyads, and the names of people and places they mention in their conversations, are pseudonyms.

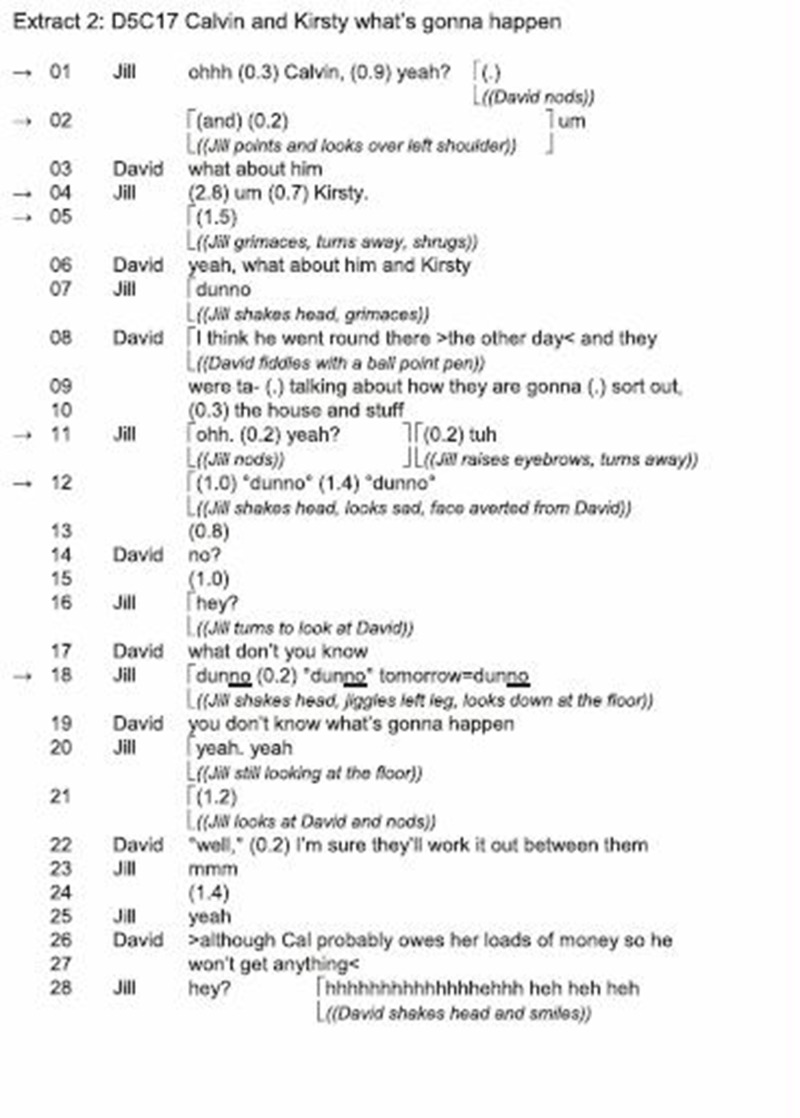

Extract 2.

D5C17 Calvin and Kirsty what's gonna happen

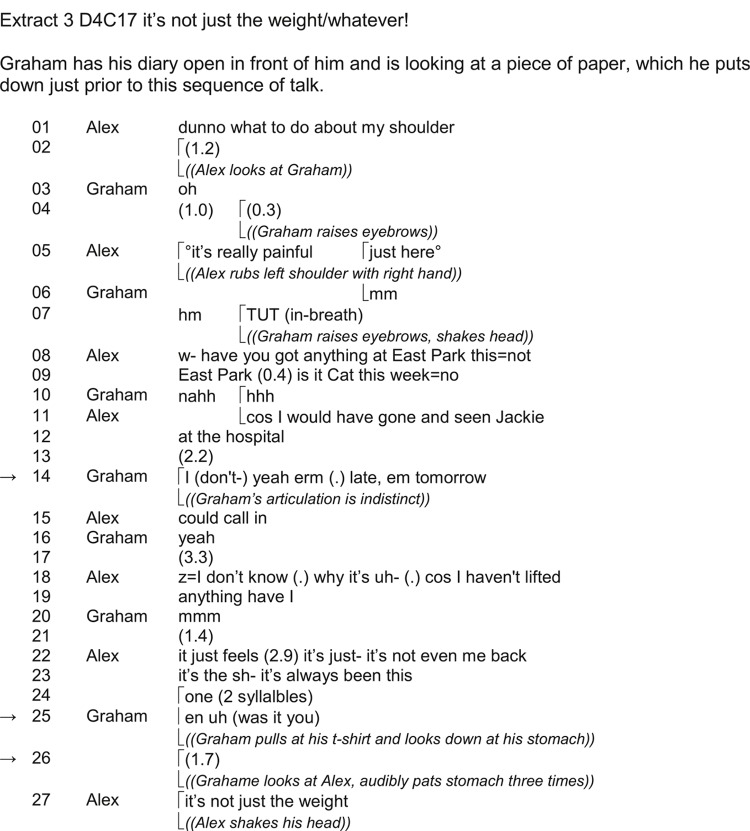

Extract 3.

D4C17 it's not just the weight/whatever!

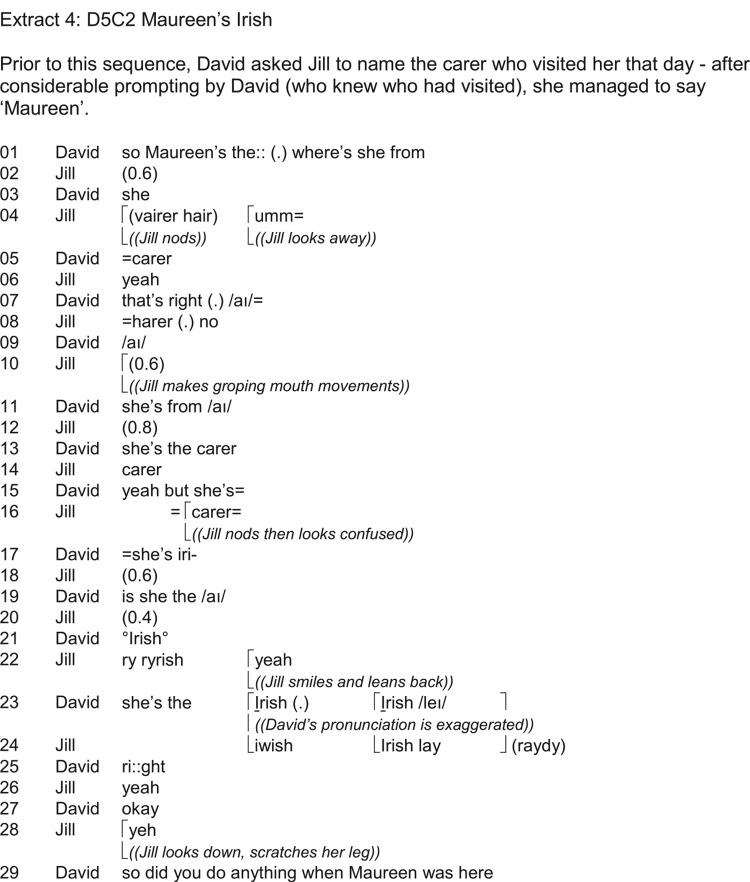

Extract 4.

D5C2 Maureen's Irish.

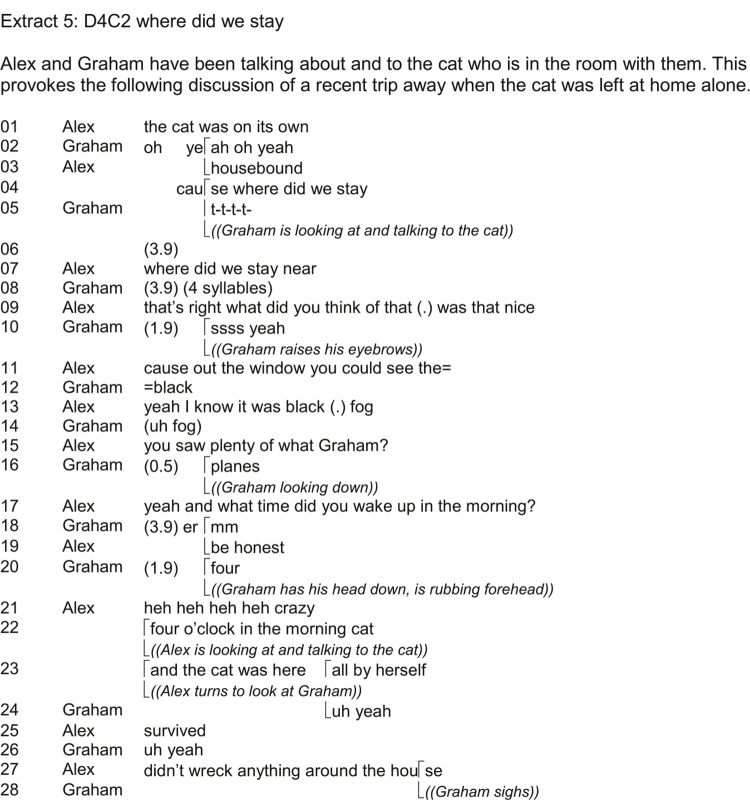

Extract 5.

D4C2 where did we stay.

Extract 1.

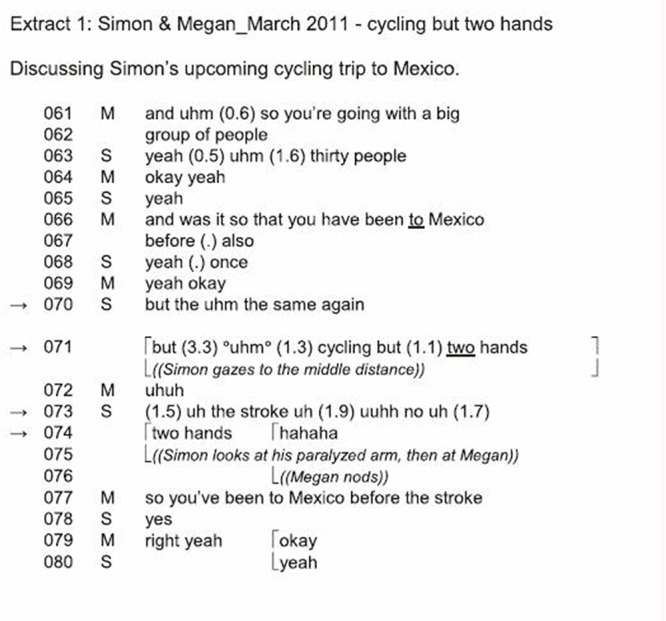

Simon & Megan_March 2011 - cycling but two hands.

Analysis

The analysis first presents examples of the turn construction methods deployed by three people with agrammatism as they take an extended turn, in order to recount a past event in which they were involved, to initiate a discussion about a current personal situation, or to have a disagreement. These extracts represent aphasic turns that pass off in relatively unproblematic fashion; although there is repair, it does not threaten to become the sole focus of the interaction. This is then followed by two examples of test question sequences, to illustrate the effect of these on the turn construction practices of two of the speakers whose extended turns are also discussed.

Extended turns

Extracts 1–3, below, have been chosen to illustrate extended agrammatic turns that pass off with relatively little need for repair of mutual understanding, and the verbal and non-verbal resources deployed in their construction.

Extract 1 is taken from a conversation between Simon, a 41-year-old man who had a stroke 5 years before this data was collected, and Megan, a Finnish speech and language therapy (SLT) student on a 3 month exchange trip to a UK university. Simon was a participant in the UCL Conversation Therapy Project; the data presented here were collected 3 years after his involvement, when Megan visited him to record conversation data for her student project. The following builds on and further develops an analysis of extended turns in Simon’s talk presented in Widenius (2012).

Prior to this extract, Simon has been telling Megan about a cycling trip to Mexico he will go on in 4 days time. Over lines 061 to 065, Megan asks and Simon answers a question about how many people are going on the trip. At lines 66–67, Megan asks Simon another question (“… you have been to Mexico before (.) also”) to which he answers “yeah (.) once” (line 68). Megan’s acknowledgement of this, “yeah okay” (line 69) appears to treat Simon’s answer as sufficient. However given that it is topic talk and it is Simon’s story to tell, this appears to be a place at which more talk from Simon may be expected. And indeed, Simon self selects, taking the floor at line 70 to begin an extended turn (marked by arrows in the transcript), telling Megan more about his prior trip to Mexico. The turn begins with “but the uhm the same again.” By beginning his turn with “but,” Simon takes and holds onto the conversational floor with a word that strongly projects more talk is to come, while signaling that what is upcoming will be in contrast to what has gone before (Mazeland & Huiskes, 2001). This is a device noted by Beeke et al. (2007a) to be of particular use to speakers with aphasia. With the formulaic expression “the same again,” he ties his meaning to the context of prior turns (the trip to Mexico), in this way conveying meaning over and above that contained within the formulaic phrase. His turn continues with “but (3.3) °uhm° (1.3) cycling but (1.1) two hands” (line 71), during which his gaze is fixed on the middle distance, as is characteristic of a solitary word search sequence (Laakso & Klippi, 1999). Once again turn-initial “but” acts as a strong signal of turn continuation; a pause of 3.3 s duration follows without Megan intervening. After further filled and unfilled pauses, Simon says “cycling,” a nominalised form that could be verb or noun (there is no grammatical context to differentiate the two), a common phenomenon in agrammatic speech. Whatever the word class, the item is highly relevant in terms of tying the ongoing turn to prior context while adding to its meaning. At line 71 “but” is used for a third time to signal continuation, however here it also appears to create contrast when followed by the phrase “two hands” (stress on the word “two” is indicated by underlining in the transcript). This stress suggests something of central relevance to the story Simon is telling. In response, at line 72, Megan produces a passing turn (“uhuh”); at this point Simon is looking skywards, once again engaged in a solitary word search, and thus signaling a turn-in-progress.

After a 1.5 second pause, Simon continues with “uh the stroke uh (1.9) uuhh no uh” (line 73). Here, the word “no” appears to function to negate the concept of the stroke, thus invoking a time before it happened. After a 1.7 second pause, he again says “two hands,” this time while looking down at his paralysed arm then up at Megan, before laughing (lines 73–74). Here, eye gaze appears to tie together the object under scrutiny, his paralysed arm, with the turn so far, which has conveyed the concept of a time before the stroke, when he had two hands (to cycle with). The direction of his eye gaze also serves to direct Megan’s attention to this, and to signal the end of his turn. By then redirecting his eye gaze towards Megan, he invites her back into the conversation after considerable solitary word finding activity (Laakso & Klippi, 1999), and also after an extended telling. The sequence ends with Megan offering a grammatical version of what she thinks Simon means to say, for him to accept or reject (“so you’ve been to Mexico before the stroke,” line 77). Over lines 78 to 80 we see a short series of sequence-closing acknowledgments of this reading of his meaning.

Simon’s turn at lines 70–74 is clearly agrammatic, although it may contain an isolated verb form (cycling). Despite this, he is able to package the elements of the turn into a construction that conveys a complex idea – he has done this same cycling trip to Mexico once before, prior to his stroke, when he had the use of both hands; it is the current ability to use only one hand that constitutes the difference (“same again but …”). He achieves this extended telling by using verbal resources such as nouns, numbers, a formulaic expression, and words like “but” to mark continuation and contrast, and “no” to negate an event (here, his stroke) and thus indicate a time before it occurred. Arguably, given his agrammatism, he does not have the lexico-grammatical resources to express this complex concept in a straightforward linguistic way. He successfully holds on to his extended turn by using continuative intonation, fillers and eye gaze (averted at the points when Megan is to remain in her role as recipient). In this way, Simon’s resources for constructing an extended turn, to tell of an event that occurred to him in the past, appear almost identical to those of Roy, the speaker with agrammatism discussed in Beeke et al. (2007a, 2007b).

Extract 2 illustrates the extended turn construction practices of a second speaker with more severe agrammatic aphasia, Jill, a 57-year-old woman who had a stroke 3 years prior to her involvement in data collection. She is in conversation with her adult son, David. Prior to this extract, Jill has initiated a topic by writing and then reading aloud the name Eleanor, but has not conveyed to David what it is about Eleanor that she wishes to discuss. In response, David has shown her how to spell Eleanor. This sequence of writing and reading has just come to an end prior to the initial turn of Extract 2.

The extract begins with topic-initiating talk from Jill, marked by the use of turn-initial “oh” and the introduction of a referent “Calvin” (line 01). Reference is established explicitly (Auer, 1984) before Jill continues her turn; she says “yeah?” with marked rising intonation, to which David responds with a nod. A second referent is potentially implicated by a cut off word that could be “and,” accompanied by a gesture over her left shoulder (line 02), however at this point Jill’s turn runs into difficulty, marked by a filled and unfilled pause. The turn remains incomplete, which prompts David to ask “what about him” (line 03); it is clear from his question that he understands the topic-initiating function of Jill’s turn. Following a pause of 2.8 s, Jill produces a second referent, “Kirsty.” This is followed by marked non-verbal behaviour; she grimaces, turns away from David and shrugs. The effect is that of a non-verbal “comment” on the topic of Calvin and Kirsty, and it appears that this conveys an assessment of some unfortunate event concerning them. In line 06, David asks “yeah, what about him and Kirsty.” Thus, he pieces together the fragmented parts of Jill’s extended turn (lines 01–02 and 04–05) to show he has recognised Calvin and Kirsty together to be the topic, but he offers no response to Jill’s nonverbal comment.

Following this, Jill responds with “dunno,” grimacing once again and shaking her head (line 07). The effect is not one of professed lack of knowledge of events concerning Calvin and Kirsty; “dunno” appears to express uncertainty as to the outcome of the situation, although the event in question remains unspoken. Jill’s non-verbal demeanour conveys concern. Over lines 08–10 it becomes clear that David knows what Jill is referring to, as he explains to her that Calvin has been to talk to Kirsty about “sorting out” the house (presumably they are splitting up). His tone is soft and his delivery is hesitant, suggesting dispreference for the topic they are discussing; at the same time he is fiddling furiously with a ballpoint pen. Jill’s subsequent “ohh … yeah?” (line 11) suggests that this meeting is news to her, which may also explain David’s reaction; he appears to be the first person to tell Jill of this development.

Over lines 11–12, Jill further expresses her feelings about Calvin’s and Kirsty’s situation by tutting, raising her eyebrows and averting her face from David; she looks sad as she quietly says “dunno (1.4) dunno”. After a lapse in the conversation, David says “no?” (line 14), as if prompting Jill to continue. After a 1 second pause, Jill returns her gaze to David and says “hey?” (line 16). David is subsequently direct in his response, asking Jill “what don’t you know” (line 17). This prompt may stem from his seeming discomfort with the topic, or may be an attempt to get Jill to say something more, or at least more content-rich than “dunno”, a word she uses with regularity, and which may serve as a means of taking or continuing a turn in the presence of severe expressive aphasia. At line 18, Jill does take the floor to comment once again, and succeeds in conveying heightened concern via non-verbal behaviours and marked prosody. However, verbally, her turn is constructed yet again using “dunno,” this time alongside another word she uses often, “tomorrow”. The wider data set reveals this word is often semantically unconnected to the context in which it is used. Here, however, David makes use of the reference to the future in his response (“you don’t know what’s gonna happen,” line 19), which Jill accepts with “yeah. yeah,” while still looking at the floor (line 20). A lapse in the conversation occurs, during which Jill looks up at David and nods. David finally offers his own opinion at line 21, saying “°well° (0.2) I’m sure they’ll work it out between them.” Jill replies with “mmm” and “yeah” (lines 23 and 25); the mood remains serious. At lines 26–27, David offers another comment on the situation, concerning money (“although Cal probably owes her loads of money so he won’t get anything”). After an initial delay in responding to the meaning of David’s turn (“hey?” line 28), Jill laughs long and hard while David sits back smiling, having succeeded in lightening the mood.

Here, we see Jill, despite her severe agrammatism, initiating and pursuing an emotive topic with David over an extended sequence of turns. She introduces the topic using a turn-initial referent followed by a (non-verbal) comment, a device akin to topic-comment structure and noted in the turns of other agrammatic speakers (Beeke et al., 2003a, 2007a). She is able to continue the topic via turns consisting of verbal and non-verbal elements; it is often the non-verbal and prosodic resources that appear to convey her meaning. The verbal resource “dunno” appears to act as a means of holding the floor and overtly continuing the turn, rather than always contributing lexico-grammatical information. The word “tomorrow” recurs with great frequency in Jill’s conversations as a whole, and the semantics sometimes appears unconnected to the context of use; here though it does seem to help David interpret her meaning by conveying a sense of the future. In comparison with the extended turn uttered by Simon in Extract 1, Jill constructs her extended contribution over several turns. This may reflect the linguistic resources available to each speaker; Jill’s aphasia is more severe than Simon’s. However, Jill does succeed in introducing topic talk and elaborating on it to expand the sequence.

Extract 3 is taken from a conversation between Graham, a 63-year-old man with severe agrammatic aphasia after a stroke 4 years earlier, and his partner, Alex. Prior to the extract, they have begun to review plans for the coming week, and there is a diary open on the table in front of Graham. They do not get very far before Alex launches extended talk about pain in his shoulder, and the fact that he doesn’t know what to do about it. This develops into what Schegloff (2005) refers to as a complaint sequence. Graham constructs two extended turns as a challenge to Alex’s complaint.

In line 1, Alex initiates a troubles telling on the subject of a shoulder injury. He looks to Graham for a response during the 1.2 second pause at line 02. Graham says “oh” (line 3), and another long pause ensues (line 04) before Graham raises his eyebrows in what appears to be a signal for Alex to expand on his trouble. Already there are signs that this exchange may be running into interactional difficulty. Graham’s “oh” signals the topic to be news and yet the delayed delivery indicates a dispreffered response; the topic may not be entirely welcome. Similarly the subsequent pause of 1 second suggests trouble; Alex might be expected to continue talking about his shoulder but doesn’t, possibly because Graham’s response did not immediately signal that more talk would be welcome. After Graham’s eyebrow-flash, Alex finally expands with “it’s really painful just here” (line 05), while rubbing his left shoulder. Graham acknowledges the turn in overlap with a minimal “mm” (line 06) before delivering a loud tutting sound followed by an audible in-breath, while raising his eyebrows and shaking his head (line 07). Graham’s turn does not appear to be designed to convey sympathy, despite this being a troubles telling, and again there are signs that the topic may be unwelcome. Alex then checks “have you got anything at East Park … is it Cat this week=no” (lines 08–09), a reference to a hospital and a likely outpatient appointment of Graham’s. Alex already appears to know the answer is no, which Graham confirms (line 10). Alex follows this with an explanation of the reasoning behind his comment, “cos I would have gone and seen Jackie at the hospital” (lines 11–12). At line 14 after a 2.2 second lapse in the conversation, Graham volunteers an extended turn “I (don't-) yeah erm (.) late, em tomorrow”. Despite the agrammatic nature of the turn and the indistinct quality of Graham’s articulation (due to dyspraxia, a motor speech disorder resulting in effortful and imprecise articulations that commonly co-occurs with agrammatism), Alex is able to offer a version of what he thinks Graham means to say (“could call in”, line 15), which is accepted.

After a 3.3 second lapse, Alex resumes his troubles telling with a comment on his incomprehension about the cause of the pain: “I don’t know (.) why it’s uh- (.) cos I haven't lifted anything have I” (lines 18–19). This turn, with its final tag question is clearly formulated to elicit a preferred response, agreement, which here requires an answer in the negative. However, Graham responds with a passing turn, “mm” (line 20). A 1.4 second pause ensues before Alex continues his telling over lines 22–24 with more explicit reference to the site of the pain.

Towards the end of Alex’s turn, Graham makes a second extended contribution to the conversation, saying “en uh (was it you) (1.7)” (lines 25–26). The words are semantically non-specific, imprecisely articulated and delivered with equal stress on each syllable (syllable-timed speech is a feature of dyspraxia). However, the turn is augmented by accompanying gestures that render its meaning clear; Graham vigorously tugs at the portion of his own t-shirt that sits over his stomach, while looking down at this gesture. In the 1.7 second pause, he looks up at Alex while audibly patting his own stomach three times (line 26). He is telling Alex that it is his weight that is the cause of the shoulder pain. Alex has no difficulty understanding the message; he responds with “but it’s not just the weight” (line 27). Graham’s rejoinder at line 28 is an emphatic “yes!’ accompanied by patting of his own shoulder and shaking of the head, which appears to reiterate his opinion that Alex’s shoulder pain is linked to his weight.

Alex quietly and partially concedes the point with “yeah well,” before going on to suggest another cause, “it’s damage done through pushing you in the wheelchair as well those years” (line 29–30). This appears to (indirectly) signal that some of the responsibility for the shoulder pain is Graham’s, and in the context of Graham’s prior assertion about the “fault” being Alex’s own, the interaction appears to have entered a phase where blame is to be apportioned. Graham’s response is marked; in overlap with the end of Alex’s comment about the wheelchair, he sighs loudly and forcefully, while taking up a body posture that appears very “arched”; he looks pointedly to the middle distance above and to the right of Alex, while pursing his lips in a mock smile (line 31). Alex’s verbal response reinforces a view that Graham’s turn, though non-verbal, has the power to convey disapproval and anger; he says “I know it is!,” and his own intonation conveys rising frustration and defensiveness (line 32). After a 1 second pause at line 33, Graham responds with two short laughter particles but the effect is not one of amusement. He then raises his forearm so it is pointing vertically upwards with his hand held out, palm facing upwards. Having struck the pose, he fixes Alex with a stare and says “whatever” in what sounds like an American accent. The onset of the word is loud, the /t/ is realised as a glottal stop and the final vowel is a significantly lengthened. His production invokes a relatively newly stereotyped usage of “whatever” to convey extreme indifference to what has been said, or a lack of care, and perhaps also serves to close down a topic of talk (an argument) without admitting blame. Alex rather neutralises the effect of this turn by quietly repeating “whatever” (line 36) while not looking at Graham. After a short pause, Alex adds “but it’s painful enough to cause problems and I haven’t just suddenly put on more weight” (lines 38–39), thus reasserting his view.

In this extract we see Graham constructing turns that, despite his severe agrammatism, allow him to voice strong opinions and engage in a dispute. His extended turns are multimodal, constructed using words, gesture, marked prosody, facial expression and audible exhalations. These resources succeed in conveying his meaning; Alex does not indicate any difficulty with understanding Graham’s assertions about his weight or anger about being implicated in causing the shoulder injury.

Extracts 1, 2 and 3 have illustrated the turn construction methods deployed by three different people with agrammatism as they take extended turns at talk that pass off in relatively unproblematic fashion. Although there is repair (the non-aphasic speaker often produces a version of what they think the person with aphasia meant to say, for acceptance or rejection), it does not threaten to become the sole focus of the interaction. For all three speakers with agrammatism, turns are “multimodal” in the most inclusive sense; every resource from lexis to prosody, facial expression and body posture, is harnessed in order to construct a turn at talk. And in these examples, as in others in the literature on agrammatic conversation, a lack of grammatical resources does not appear to unduly hinder turn construction.

Test question sequences

However, turn construction may prove to be problematic, and this can occur when the talk of a speaker with agrammatism is constrained by the sequential context of a conversation partner’s prior turn. Extracts 4 and 5, below, have been chosen to illustrate what happens to the turn construction practices of two of the same speakers, Jill and Graham, when asked a test question by their respective conversation partners, David and Alex.

Extract 4 is taken from a second conversation between Jill and David. In it David invites Jill to say where Maureen, one of Jill’s carers, is from – she’s Irish – and uses phonemic cueing to scaffold Jill’s production of the words (Ireland, Irish) and phrase (Irish lady) that the test question sequence requires of her.

In line 01 David asks Jill a question about Maureen, “where’s she from”. As the sequence unfolds it becomes clear from his very specific prompts that he knows that Maureen is from Ireland. Thus, this is a test question, or known answer sequence. His turn is initially constructed as an utterance completion exercise (“so Maureen’s the::”), evidenced by the fact that it is a statement delivered as an intentionally incomplete turn, ending with a determiner (with an elongated vowel) that clearly projects a noun is to follow, and is to be spoken by Jill. However, he reformulates this to a test question to which the known answer is Ireland, perhaps recognising the ambiguity of his incomplete utterance in the context of turns prior to this extract, in which Maureen has been identified as the carer. The utterance could be completed either with the word carer or (as we see later) with the intended word Irish. At first there is no response from Jill (line 02) to the test question, however after a 0.6 second pause, as David says “she” (line 03), Jill says something that sounds like “vairer hair” (line 04), while nodding. She then produces a filler and looks away. It is not clear if Jill’s turn is an attempt at the word carer or even something like “fair hair” (i.e. a description of Maureen), but it is not an attempt to say the word Ireland, or even Irish. David appears to interpret it as an attempt at carer, which he repeats in line 05 and Jill acknowledges in line 06. David’s subsequent “that’s right” (line 07) confirms the test-like quality of the interaction. He follows this with the initial vowel of the word Ireland (line 07), thus seeking a scaffolded answer to the test question in line 01 (“where’s she from”). However, there is no other context at this point to signal that the vowel /aı/ is the beginning of the answer to this question. Jill hasn’t picked up on the shift from talking about carers to the need to produce the word Ireland; she attempts and rejects a second production of the word carer at line 08 (“harer (.) no”). At line 09, David repeats his isolated phonemic cue. This is followed by articulatory groping from Jill, during a 0.6 second pause. At line 11 David tries again, this time shifting from a test question to an utterance completion combined with a phonemic cue, saying “she’s from /aı/”. A 0.8 second pause follows where Jill’s response is expected but not forthcoming (line 12).

When Jill does not produce the word Ireland, David backtracks at line 13 to confirm “she’s the carer”, and Jill repeats carer in acknowledgement (line 14). At line 15, David resumes with “yeah but she’s,” his “but” signalling that there is unresolved interactional business to deal with that has been interrupted (Mazeland & Huiskes, 2001). There is no discernible gap between the end of David’s turn and the start of Jill’s response; she comes in quickly with “carer,” and looks confused (line 16). David’s subsequent turn delivers an utterance for completion plus a phonemic cue (as in line 11), but it appears that the word required is now Irish, not Ireland (“she’s iri-”). Jill is silent (line 18) and there are no non-verbal signals from her; she does not appear to know that something is required of her. Given the lack of response, David makes one more attempt, this time with a question format (“is she the /aı/,” line 19) before saying the target word softly under his breath (line 21). At this point Jill appears to know what is needed to complete the exchange; she attempts to say Irish (“ry ryrish”) before adding “yeah,” smiling and sitting back in her chair. However, the sequence does not end. In line 23, David first produces the word Irish in isolation and then in a phrase (Irish lady) which he leaves incomplete to prompt Jill to say “lady”. Throughout his turn his articulation is slow and clearly enunciated. As is sometimes seen in people with dyspraxia, Jill is able to shadow his talk to the point where her versions of the words almost completely overlap with his (line 24), which results in correct production of Irish and minor distortion of lady (“raydy”). Finally comes the evaluation phase of the known answer sequence; David says “right” (line 25) and “okay” (line 27), to which Jill responds with similar acknowledgements. He then initiates a new, but related, topic by asking Jill if she did anything when Maureen was there.

This test question/utterance completion sequence on the topic of Maureen’s nationality takes 27 turns to reach closure, and at several points within it the task changes from “saying Ireland” to “saying Irish (lady),” and from answering a question to completing an incomplete utterance. Because both Jill and David had equal access to the knowledge under discussion, no news is exchanged; from the start of the sequence the focus is on Jill participating in a conversation by producing pre-determined words. Jill’s responses, where present, have consisted of turns constructed of nouns or adjectives, and perhaps as a result of being put “on the spot,” her dyspraxia has appeared much more prevalent than it was in Extract 2. David is able to assist Jill’s participation by providing phonemic cues and versions of the required words for correct production because he knows the target words. The scaffolding provided by this pedagogic sequence appears to be a double edged sword. It allows David to invite Jill to join in a conversation, and it removes any potential difficulty for him in understanding what she is talking about. However, it limits the structure and content of Jill’s turns, and lends the interaction an institutional (didactic) rather than an informal character. This appears facilitative in that there is less interactional work for Jill to do to participate in conversation with David. As a consequence, however, Jill does not deploy the range of multimodal turn construction resources seen in Extract 2, and word finding and motor speech difficulty come to the fore. It is notable that Jill does not appear frustrated or upset, as is sometimes the case for people with aphasia in such sequences (see for example, Lock et al., 2001), although at one point she does look confused about what is required of her (line 16).

Extract 5 is taken from a second conversation between Graham and Alex. In it Alex introduces the topic of a trip they made that seems to have been less than enjoyable, possibly due to them staying in accommodation near an airport. Although this was a shared experience, Alex asks Graham a series of test questions about the event, to elicit target nouns (where they stayed, what they could see out of the window, and what time Graham woke up).

At line 01 Alex introduces a new topic by commenting “the cat was on its own”. Graham responds with “oh yeah oh yeah” (line 02), which is overlapped by Alex’s next turn, “housebound” (line 03). In line 04, Alex poses a question, “cause where did we stay”, while Graham is looking at and making noises at the cat (line 05). The pronoun in Alex’s question indicates this was a joint experience and nothing about the turn or the exchange so far suggests that Alex is having difficulty remembering where they stayed. These characteristics suggest that his turn is a test question that is designed to invite Graham to contribute further to the newly established topic. There is a pause of 3.9 seconds but no answer is forthcoming from Graham (line 06). Subsequently, Alex amends his question to make its focus more specific (“where did we stay near?” line 07). After a pause of 3.9 seconds Graham responds; the four syllables he produces are unintelligible to the analyst but appear to be fully understandable to Alex, who moves to the evaluation phase of the test question sequence, commenting “that’s right” (line 09). The first test question sequence is at an end. Alex then seeks to further expand the conversation by asking Graham’s opinion of where they stayed, via an open question “what did you think of that”. Before Graham can answer, Alex reframes this as a yes/no question “was that nice” (line 09). After a pause of 1.9 seconds, Graham produces a prolongation of the phoneme /s/ followed by “yeah” (line 10). His intonation and raised eyebrows appear to suggest only partial agreement. In line 11, Alex continues the conversation with what appears to be another test-like turn, formulated as an utterance completion, “cause out the window you could see the.” The incompleteness of this turn coupled with continuative intonation and a final determiner suggest that Graham is being invited to complete it with a noun. In response, Graham says “black” (line 12), an adjective. Alex’s response reinforces a sense that Graham has not produced the target word; he says emphatically “yeah I know it was black” before adding “fog” (line 13). This invokes their equal access to knowledge on the subject, and appears to be designed to incorporate Graham’s turn into the conversation despite it not being the required word for completion of Alex’s incomplete turn. Graham responds by repeating the word “fog”, but it is distorted by his dyspraxia (line 14).

Alex then delivers a second invitation to Graham to say the word, this time using a test question, “you saw plenty of WHAT Graham?” (line 15). His increased rate and volume suggest a new urgency to the request for the target noun. In addition, by using Graham’s name, Alex appears to be launching a stronger form of questioning than before. After a pause, Graham looks down and responds “planes” (line 16). Alex then moves to the evaluation phase of this second test question sequence, saying “yeah” (line 17), before posing the final test question seen in this extract, “and what time did you wake up in the morning” (line 17). Graham’s response is delayed, and he appears to be having word finding difficulties (line 18). Alex adds “be honest” in overlap with the fillers in Graham’s turn (line 19). After another 1.9 second pause, Graham gives the single word answer “four” (line 20). Alex’s laughter and assessment “crazy” (line 21) imply that four (o’clock) was the target answer, as does his turn directed towards the cat (“four o’clock in the morning cat”, line 22). Alex then says “and the cat was here all by herself” (line 23), to which Graham responds “uh yeah” (line 24). In lines 25 and 27 Alex continues with topic closing comments on the cat’s stay at home alone. Graham’s acknowledgement of these turns consists of a minimal “yeah” and a sigh (lines 26 and 28).

These three test questions and one utterance completion occur in a sequence of talk on a discrete topic (a less than enjoyable trip) that is neatly bookmarked by reference to the cat being left alone. Alex introduces the topic, and invites Graham’s participation in topic talk by deploying pedagogic methods. The aim of inviting participation is successful, and results in Graham producing different turn constructions to those seen in Extract 3. Here the turns consist of target nouns and a number. As was the case for Jill, this type of sequence appears to highlight both word finding difficulty and dyspraxia, and Graham does not deploy the range of verbal, vocal and non-verbal turn construction practices seen in Extract 3. When he attempts to move beyond the sequential constraint of completing Alex’s turn by offering a comment on the darkness (or possibly the fog), this is acknowledged but put to one side, and the test question sequence is reinstated. The difference between Extracts 3 and 5 is also highlighted if we consider issues of face and interactional competence. In the former Graham is an equal partner in a dispute, putting forward views which are understood without difficulty. However, in Extract 5 his identity as a linguistically impaired interactant with minimal resource to take a turn at talk is placed to the fore. For his conversation partner, Alex, the test questions appear to be motivated by the aim of “making conversation”. His turns about and directed towards the cat, along with the comment “be honest” and the assessment “crazy”, may represent some attempt to “disguise” a pedagogic sequence as informal chat. Only the first two test questions are evaluated for the acceptability of the answer, with “that’s right” (line 09) and “yeah” (line 17).

Discussion

The first three extracts in this article have illustrated the turn construction methods deployed by three different people with agrammatism as they take extended turns at talk that pass off in relatively unproblematic fashion; although there is repair, it does not threaten to become the sole focus of the interaction. For all three speakers with agrammatism, turns are multimodal in the most inclusive sense; every resource from lexis to prosody to facial expression and body posture is harnessed in order to construct a turn at talk. And in these examples, as in others in the literature on agrammatic conversation, a lack of grammatical resources does not appear to hinder turn construction (Beeke et al., 2003a, 2007a). With such turn construction devices at their disposal, these speakers are able to recount past events, to initiate discussion about current issues, and to have disagreements. In these extracts, although aphasia clearly has an effect on turn construction it does not become the sole focus of the interaction; each speaker with aphasia and their conversation partner is able to go about their everyday interactional business without linguistic non-competence coming to the surface of talk.

The extracts containing test question sequences sit in contrast to this. In them we see two of the same speakers involved in sequences where their conversation partner initiates talk on a new topic and invites the participation of the person with aphasia in that talk, by using test questions and turns designedly left incomplete. This association between test questions and topic initiation/development represents a different context for the use of test questions to that described by Bauer and Kulke (2004), though it has parallels with the findings of Burch et al. (2002). In Bauer and Kulke’s data, test questions appear to be sited within sequences where a topic is already established, and sometimes after repair work has been undertaken by the person with aphasia. Our examples appear to be primarily oriented around topic and topic expansion, and are only triggered by the need for repair where topic talk appears to be in trouble (when Jill’s response is a word that does not fit the topic of Maureen’s nationality, for example). Despite these differing motivations for the deployment of test questions, the consequences appear to be the same. No news is imparted despite the use of questioning, a common device for dealing with an imbalance of information (Heritage, 2012b). This is because both parties have equal access to the knowledge from the beginning of the sequence. Informal conversation appears to have been halted in order to focus on dealing with aphasia. However, as Aaltonen and Laakso (2010) conclude in their discussion of “exam halts,” sometimes a behaviour that appears to expose the linguistic difficulties of an aphasic interlocutor can in fact be motivated by a conversation partner’s wish to promote interactions where the person with aphasia appears competent. In Aaltonen and Laakso’s (2010) data, competence was construed by the conversation partners as the person with aphasia completing self repair, in our data it appears to be construed as participating in talk on a set topic.

According to Heritage (2012a), taking an unknowing epistemic stance, such as asking a question, invites an interlocutor to elaborate on a topic and thus has the potential to lead to expansion of an interactional sequence. It appears in our data that the conversation partner’s motivation for asking a test question is to invite a person with aphasia to contribute to conversation. In the context of potential difficulties in communicating, knowledge to which both parties have equal access appears to offer safe ground from which to launch such an invitation to talk. The way in which test questions are designed to project a single known answer reveals the questioner’s unknowingness to be an epistemic stance rather than a genuine lack of access to knowledge. In the kinds of aphasic conversations that form the focus of this article, both speakers have equal epistemic status since they have shared (and sometimes simultaneous) experience of the person, object or event being discussed.

In our data, test questions result in extended sequences often incorporating correct production sequences (Lock et al., 2001) when a known answer is mispronounced due to dyspraxia, and they appear to limit opportunities for exchange of news. However, we see no overt signs of frustration or negative emotion from the people with aphasia in these examples, unlike those reported by Lock et al. (2001). Thus our data appear to support Bauer and Kulke’s (2004) conclusion that for some interactional partnerships, and in some contexts, test questioning may be accepted by a conversation partnership where one person has aphasia. Unlike Bauer and Kulke’s (2004) examples of “language exercises” incorporated into a joint activity such as completing a puzzle (which may legitimise the overt focus on what is essentially a naming task), in our data there is no concurrent physical activity. However, for Alex and Graham, it is possible that the interactional joint activity of reminiscing about their trip may reduce any threat to face engendered in the sequence of test questions that Alex asks. This reinforces the idea that the main motivation for using test questions in these data is to scaffold the person with aphasia in joining in with a new topic of conversation, rather than practising saying words in an attempt to improve language skills. The sequence between David and Jill appears to have greater potential to constitute a threat to face, since David launches a number of test questions and designedly incomplete utterances focused on a single word (Irish) before Jill is able to participate in the topic of conversation. Whereas David asks a series of test questions in order to elicit this one word, Alex asks three successive test questions, each to elicit a different word. However, neither Jill nor Graham displays any overt sign of negative emotion. Further systematic exploration of the data set may reveal test question sequences that are associated with a threat to face, and it will be important to explore how these differ from the examples here in terms of interactional context.

If the motivation is to have a conversation, we should consider whether test questions are influenced by the fact that the interactants are being video recorded; these sequences could be about “making conversation” for a third party (i.e. the camera, and by extension the analyst). The Conversation Therapy database includes video recordings of therapy sessions in which test questions were discussed with these dyads. Although these ethnographic data have yet to be explored systematically for insights into the motivations for their use, there is one revealing discussion with Alex and Graham, which offers some pointers. In it, Alex identifies test questions as a routine part of his conversations with Graham. Thus, they report engaging in such sequences when the camera is not present. In his own words, Alex says that he asks “the obvious,” and that he does it “to encourage communication”. In the same discussion the speech and language therapist asks Graham how he feels about being asked the obvious, and he conveys via facial expression and vocalisation that it annoys him – Alex glosses Graham’s meaning as “drives him nuts sometimes”, which Graham readily accepts. This suggests that test question sequences have the potential to be emotive for Graham and Alex in some contexts, although this is not seen in the data presented here.

Clinical implications

These data support Bauer and Kulke’s (2004) conclusion that test questions may be acceptable to people with aphasia and their families in some interactional contexts. However, such sequences have the potential to be problematic precisely because almost all individuals, regardless of aphasia type or severity, have persistent word finding difficulties, and many will also be unable to achieve correct production of a word in the face of a motor speech difficulty, even when a target has been produced for immediate repetition.

If used to promote talk on a new topic, test questions may constitute a necessary feature of interactions early in the process of adjusting to life with aphasia, not necessarily against the wishes of a speaker with aphasia. Topic initiation is known to be difficult for people with aphasia (Barnes, Candlin, & Ferguson, 2013), and this may result in a higher burden on conversation partners to begin conversations. When the aphasia is acute and severe, one way to help a family member with aphasia to join in with conversation would seem to be to choose a shared topic and ask questions about it. At points and in certain contexts, SLT adopts a similar approach, setting a joint focus on pictorial materials for example, and attempting to promote naming or description. The premise is very different, in that the underlying aim is to improve access to language and techniques are motivated by theoretical models of language processing. But on the interactional surface, it might look quite similar to asking “the obvious,” as Alex puts it.

Over time it is possible that pedagogic sequences might become an integral, and somewhat unconscious, part of what conversational partnerships do at home in the face of aphasia. This may explain why for some families in some instances, test questions and other pedagogic behaviours are not associated with frustration or negative emotion. However, if a person with aphasia later reaches a point where, given space, they are sometimes able to initiate their own topics, or design turns that extend a topic without answering a (test) question, the persistence of pedagogic scaffolding may mask this interactional ability. Thus test questions may change over time from being supportive of participation in conversation to limiting it.

This idea that some conversational partnerships may get “stuck” over time in interactional patterns that have outlived their usefulness clearly needs further research. However, it reinforces the importance of conversation-based interventions, such as that described by Lock et al. (2001), and Better Conversations with Aphasia (www.ucl.ac.uk/betterconversations/aphasia) which, crucially, invite both interactants to view, reflect and comment on what they do in conversation together and why, prior to setting therapeutic goals. If a dyad expresses no negative emotion when reflecting on behaviours like test questioning, or correct production sequences, eradicating test questions may not be a priority for therapy even if we, as analysts and therapists, perceive such behaviours to be problematic. However, if identified by a dyad as problematic, test question sequences may be amenable to therapeutic modification or eradication (Burch et al., 2002), with the knock-on effect that a speaker with aphasia then has the opportunity to initiate topics, and to make use of a full range of multimodal resources to construct turns. The data in this article remind us that, in an optimal sequential context, even a speaker with a severe aphasia can achieve much in terms of taking a turn at talk.

Acknowledgements

The analysis of extracts presented in this article builds on and extends the work of a number of masters students of SLT at University College London, who undertook their final year dissertations with the authors: Vicki Edwards, Sarah Lambert, Abenet Tsegai, Maria Widenius, and Amie Wilson. We acknowledge their earlier work including transcriptions, which the first author has refined for use in this article. We thank Sarah Lambert and Abenet Tsegai for their reviews of the literature on test questions, which have been incorporated into the background section.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no declarations of interest. This research was funded by the Stroke Association http://www.stroke.org.uk (TSA 2007/05, 2008–2011).

References

- Aaltonen T., Laakso M. Halting aphasic interaction: Creation of intersubjectivity and spousal relationship in situ. Communication and Medicine. 2010;7:95–106. doi: 10.1558/cam.v7i2.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer P. Referential problems in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics. 1984;8:627–648. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes S., Candlin C., Ferguson A. Aphasia and topic initiation in conversation: A case study. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2013;48:102–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A., Kulke F. Language exercises for dinner: Aspects of aphasia management in family settings. Aphasiology. 2004;18:1135–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Beckley F., Best W., Johnson F., Edwards S., Maxim J., Beeke S. Conversation therapy for agrammatism: Exploring the therapeutic process of engagement and learning by a person with aphasia. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2013;48:220–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2012.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeke S. Aphasia: The pragmatics of everyday conversation. In: Schmid H.-J., editor. Cognitive pragmatics [Handbook of pragmatics, Vol. 4] Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter; 2012. pp. 345–371. [Google Scholar]

- Beeke S., Maxim J., Best W., Cooper F. Redesigning therapy for agrammatism: Initial findings from the ongoing evaluation of a conversation-based intervention study. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2011;24:222–236. [Google Scholar]

- Beeke S., Wilkinson R., Maxim J. Exploring aphasic grammar 1: A single case analysis of conversation. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics. 2003a;17:81–107. doi: 10.1080/0269920031000061795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeke S., Wilkinson R., Maxim J. Exploring aphasic grammar 2: Do language testing and conversation tell a similar story? Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics. 2003b;17:109–134. doi: 10.1080/0269920031000061786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeke S., Wilkinson R., Maxim J. Grammar without sentence structure: A conversation analytic investigation of agrammatism. Aphasiology. 2007a;21:256–282. [Google Scholar]

- Beeke S., Wilkinson R., Maxim J. Individual variation in agrammatism: A single case study of the influence of interaction. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2007b;42:629–647. doi: 10.1080/13682820601160087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeke S., Wilkinson R., Maxim J. Prosody as a compensatory strategy in the conversations of people with agrammatism. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics. 2009;23:133–155. doi: 10.1080/02699200802602985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch S.,, Wilkinson R. Acquired dysarthria in conversation: Methods of resolving understandability problems. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2011;46:510–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-6984.2011.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch K., Wilkinson R., Lock S. A single case study of conversation-focused therapy for a couple where one partner has aphasia. British Aphasiology Society Therapy Symposium Proceedings. 2002. pp. 1–9.

- Damico J., Oelschlaeger M., Simmons-Mackie N. Qualitative methods in aphasia research: Conversation analysis. Aphasiology. 1999;13:667–679. [Google Scholar]

- Damico J., Simmons-Mackie N., Oelschlaeger M., Elman R., Armstrong E. Qualitative methods in aphasia research: Basic issues. Aphasiology. 1999;13:651–665. [Google Scholar]

- Denman A., Wilkinson R. Applying conversation analysis to traumatic brain injury: Investigating touching another person in everyday social interaction. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2011;33:243–252. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2010.511686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner H., Forrester M. A. Analysing interactions in childhood: Insights from conversation analysis. London: Wiley; 2010. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. On face-work: An analysis of ritual elements in social interaction. Psychiatry. 1955;18:213–231. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1955.11023008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H., Kaplan E., Barresi B. The assessment of aphasia and related disorders, 3rd edition (BDAE-3) Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin C. Conversation and brain damage. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. (Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Heeschen C., Schegloff E. Agrammatism, adaptation theory, conversation analysis: On the role of so-called telegraphic style in talk-in-interaction. Aphasiology. 1999;13:365–405. [Google Scholar]

- Heeschen C., Schegloff E. Aphasic agrammatism as interactional artifact and achievement. In: Goodwin C., editor. Conversation and brain damage. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 231–282. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J. Epistemics in action: Action formation and territories of knowledge. Research on Language & Social Interaction. 2012a;45:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J. The epistemic engine: Sequence organization and territories of knowledge. Research on Language & Social Interaction. 2012b;45:30–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hilari K., Byng S. Health-related quality of life in people with severe aphasia. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 2009;44:193–205. doi: 10.1080/13682820802008820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland A. L. Communicative abilities of daily living (CADL) Baltimore: University Park Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchby I., Wooffitt R. Conversation analysis. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson G. Transcript notation. In: Atkinson J. M., Heritage J., editors. Structures of social action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1984. pp. ix–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Kagan A. Revealing the competence of aphasic adults through conversation: A challenge to health professionals. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 1995;2:15–28. doi: 10.1080/10749357.1995.11754051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan A. Supported conversation for adults with aphasia: Methods and resources for training conversation partners. Aphasiology. 1998;12:816–830. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly D., Beeke S. The management of turn taking by a child with high-functioning autism: Re-examining atypical prosody. In: Stojanovik V., Setter J., editors. Speech prosody in atypical populations: Assessment and remediation. Albury: J&R Press; 2011. pp. 71–98. [Google Scholar]

- Klippi A., Helasvuo M.-L. Changes in agrammatic conversational speech over a 20 year period – From single word turns to grammatical constructions. Journal of Interactional Research in Communication Disorders. 2011;2:29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Laakso M., Klippi A. A closer look at the ‘hint and guess' sequences in aphasic conversation. Aphasiology. 1999;13:345–363. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson S. C. Activity types and language. In: Drew P., Heritage J., editors. Talk at work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 66–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lind M. The use of prosody in interaction: Observations from a case study of a Norwegian speaker with a non-fluent type of aphasia. In: Windsor F., Kelly M. L., Hewlett N., editors. Investigations in clinical phonetics and linguistics. London: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 373–389. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay J., Wilkinson R. Repair sequences in aphasic talk: A comparison of aphasic-speech and language therapist and aphasic-spouse conversations. Aphasiology. 1999;13:305–325. [Google Scholar]

- Lock S., Wilkinson R., Bryan K. Supporting partners of people with aphasia in relationships and conversation (SPPARC): A resource pack. Bicester: Speechmark; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon J. G. Communication use and participation in life for adults with aphasia in natural settings: The scope of the problem. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 1992;1:7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J. Assessment and treatment of sentence processing disorders: A review of the literature. In: Hillis A. E., editor. The handbook of adult language disorders: Integrating cognitive neuropsychology, neurology, and rehabilitation. New York: Psychology Press; 2002. pp. 351–372. [Google Scholar]

- Mazeland H., Huiskes M. Dutch ‘but' as a sequential conjunction: Its use as a resumption marker. In: Selting M., Couper-Kuhlen E., editors. Studies in interactional linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins; 2001. pp. 141–169. [Google Scholar]

- McHoul A. The organization of turns at formal talk in the classroom. Language in Society. 1978;7:183–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mikesell L. Conversational practices of a frontotemporal dementia patient and his interlocutors. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 2009;42:135–162. [Google Scholar]

- Parr S., Duchan J., Pound C. Aphasia inside out: Reflections on communication disability. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Prins R., Bastiaanse R. Review: Analysing the spontaneous speech of aphasic speakers. Aphasiology. 2004;18:1075–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Richards K., Seedhouse P. Applying conversation analysis. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2005. (Eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff E. A. Turn organization: One intersection of grammar and interaction. In: Schegloff E. A., Thompson S. A., editors. Interaction and grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 52–133. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff E. A. On complainability. Social Problems. 2005;54:449–476. [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff E. A. Sequence organisation in interaction: A primer in Conversation Analysis, volume 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Searle J. R. Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Sidnell J. Conversation analysis: An introduction. London: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Widenius M. Unpublished Masters Thesis; Abo Akademi University, Finland: 2012. Turn-taking and turn construction in Broca’s aphasia: Using conversation analysis to explore conversational patterns in Finnish and English. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R. Aphasia: Conversation analysis of a non-fluent aphasic person. In: Perkins M., Howard S., editors. Case studies in clinical linguistics. London: Whurr; 1995. pp. 271–292. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R. Introduction. Aphasiology. 1999;13:251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R. Interaction-focused intervention: A conversation analytic approach to aphasia therapy. Journal of Interactional Research in Communication Disorders. 2010;1:45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R., Beeke S., Maxim J. Formulating actions and events with limited linguistic resources: Enactment and iconicity in agrammatic aphasic talk. Research on Language and Social Interaction. 2010;43:57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson R., Bryan K., Lock S., Bayley K., Maxim J., Bruce C., Edmundson A., Moir D. Therapy using conversation analysis: Helping couples adapt to aphasia in conversation. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 1998;33:145–149. doi: 10.3109/13682829809179412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]