Abstract

Through an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry, we demonstrate that disease-specific survival (DSS) appears to be inferior in older adults with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) compared with younger adults. We further suggest that although DSS has improved for younger patients during the era of targeted therapies, a similar improvement is not seen among older adults.

Background

Consistent with other data sets, our own institutional series suggests that survival in patients aged ≥ 75 years with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) is inferior to that in patients < 75 years. We sought to confirm these trends through exploration of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry.

Patients and Methods

We assessed disease-specific survival (DSS) in 6204 patients with clear cell, papillary, or chromophobe mRCC diagnosed between 1992 and 2009, with the a priori hypothesis that DSS was shorter in patients aged ≥ 75 years. Analyses were further stratified by the period of diagnosis, either between 1992 and 2004 (the “cytokine era”) or 2005 to 2009 (the “targeted therapy” era). Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to determine the association between clinicopathologic characteristics and DSS.

Results

DSS was shorter in patients aged ≥ 75 years than in patients aged < 75 years (9 vs. 16 months; P < .0001). In patients 18 to 74 years, DSS was superior in the targeted therapy era compared with the cytokine era (P < .0001). However, in patients ≥ 75 years, no difference in DSS was noted between these periods (P = .90). On multivariate analysis, age ≥ 75 years, female sex, diagnosis during the cytokine era, node-positive disease, and absence of cytoreductive nephrectomy were independently associated with DSS.

Conclusion

DSS appears to be inferior in older adults with mRCC (specifically, patients aged ≥ 75 years). Furthermore, in contrast to their younger counterparts, no improvement in DSS was seen in older adults in the transition from the cytokine era to the targeted therapy era.

Keywords: Cytokine, Metastatic renal cell carcinoma, Older adults, Survival, Targeted therapy, Trends

Introduction

There has been a marked evolution in the treatment paradigm for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). A decade ago, immunotherapeutic strategies such as interleukin (IL)-2 and interferon-α (IFN-α) represented the standard of care. Several issues existed with these therapies; the efficacy of IFN-α was modest at best, and IL-2 could be administered only to individuals with reasonable performance status and limited comorbidity.1,2 Targeted therapies (directed at vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF] or the mammalian target of rapamycin) improve on the efficacy of IFN-α and can be used in a wider population of patients compared with IL-2.3 The latter is particularly relevant to older adults with mRCC, and it is widely presumed that targeted therapies have improved outcomes for this subset.

This assumption has been challenged by recent reports, however. The International mRCC Database Consortium reported an analysis of 1385 patients with mRCC who had received first-line VEGF-directed therapies.4 In patients aged ≥ 75 years, survival was numerically inferior to those patients aged < 75 years (16.8 vs. 19.7 months; P = .33). These data were based on a cohort of patients who were candidates to received targeted therapy. To explore a more heterogeneous pool, we performed an assessment of our institutional database, capturing outcomes associated with 219 patients with mRCC (irrespective of therapeutic assignment).5 Survival was significantly shorter in those patients aged ≥ 75 years (12.5 vs. 26.4 months; P = .003).

These results motivated the current exploration of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End SEER) registry. A caveat of both our institutional analysis and the International mRCC Database Consortium report is that the population of interest (patients older than 75 years) composed only about 10% of the overall population in each study. Although SEER has several limitations (ie, only survival data are captured, no treatment-related data are recorded, and so on), the data set includes a sizeable population-based sample. We approached the current report with the a priori hypothesis that patients aged ≥ 75 years have shorter disease-specific survival (DSS) than those patients aged < 75 years.

Patients and Methods

Patient Selection

The SEER data set was used to explore the a priori hypotheses of this work. Clinical and outcome data pertaining to approximately 28% of the US population is captured by the 18 SEER regional registries. These data include demographic, pathologic, and stage information, as well as disease-specific and overall survival. Notably, the SEER data set, in contrast to SEER-Medicare, does not contain data pertaining to systemic therapies.

During the period of interest, 1992 to 2009, a total of 60,587 patients with RCC aged ≥ 18 years were identified within the SEER data set. We limited our analyses to the 6204 patients with documentation of 1 of 3 histologic types (clear cell, papillary, or chromophobe).

Tumor Classification

The International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O), version 3, was used to record tumor histologic type and primary site. As previously stated, we investigated 3 clinically relevant subtypes of RCC: clear cell (ICD-O 8310), papillary (ICD-O 8260), and chromophobe (ICD-O 8317). Although Fuhrman grade was not specifically reported in SEER, an analogous scale characterizing tumors as well differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, or undifferentiated was reported and is included in the current analysis. Criteria from the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging system, seventh edition, was used to identify patients with stage IV disease. Importantly, SEER reports stage at the time of diagnosis, and therefore the patients with stage IV disease identified in our data set all had synchronous metastases.

Statistical Analysis

We explored the a priori hypothesis that patients aged ≥ 75 years had a cumulative DSS that was inferior to that of patients aged < 75 years. Given the marked evolution of the therapeutic strategy for mRCC over the past decade (ie, a shift from immunotherapy to targeted therapies), we also sought to determine if DSS was improved in older adults diagnosed during the targeted therapy era compared with those diagnosed during the era of immunotherapy. The era of immunotherapy was defined as the period from 1992 to 2004, with 1992 representing the year in which IL-2 was approved for mRCC.6 In contrast, the era of targeted therapy was defined as the period between 2005 and 2009, with 2005 representing the year in which the first targeted therapy was approved for mRCC (namely, sorafenib).7 We additionally compared clinicopathologic characteristics between the 2 groups. Continuous variables were compared using the Student t test, whereas categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. Finally, univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to determine the association between clinicopathologic characteristics and DSS. DSS was defined as the time elapsed from the date of diagnosis with metastatic disease until the recorded date of death if attributable to RCC. Patients were censored at the last date of follow-up if a date of death was not recorded and at the date of death if the cause of death was not due to RCC. Patients with an unknown cause of death were excluded from all analyses. SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses presented here. All P values are 2-sided, with a value of < .05 deemed statistically significant.

Results

Patient Characteristics by Age Group

Characteristics of the study population, stratified by the age cutoff of 75 years, are presented in Table 1. A higher proportion of patients aged 18 to 74 years were men (69.4% vs. 59.4%, P < .0001), whereas more non-Hispanic whites were represented in patients aged ≥ 75 years (77.7% vs. 71.8%; P < .0001). Although no significant differences were seen in histologic type across age groups (ie, clear cell vs. non–clear cell), a higher proportion of younger patients had undifferentiated or poorly differentiated tumors. T stage was recorded as “Tx” for the majority of patients in the cohort (66.1%), limiting inferences related to this characteristic; however, a larger proportion of younger patients had node-positive disease (31.6% vs. 23.4%; P < .0001).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Age Group

| Variable | 18-74 Years n (%) |

75+ Years n (%) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-Up Time (Mo) | |||

| Mean (± SD)/median (IQR) | 19.8 (± 23.7)/11 (4-25) | 14.4 (± 20.1)/7 (2-18) | < .0001 |

| Age | |||

| Mean (± SD)/median (IQR) | 59.4 (± 9.4)/60 (53-67) | 80.2 (± 4.2)/79 (77-83) | < .0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 3400 (69.4) | 669 (59.4) | < .0001 |

| Women | 1498 (30.6) | 457 (40.6) | |

| Year of Diagnosis | |||

| 1992-2004 | 2246 (45.9) | 527 (46.8) | .5652 |

| 2005-2009 | 2652 (54.1) | 599 (53.2) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 3506 (71.8) | 870 (77.7) | < .0001 |

| Black | 424 (8.7) | 60 (5.4) | |

| Hispanic white | 673 (13.8) | 108 (9.7) | |

| API | 233 (4.8) | 74 (6.6) | |

| AI/AN | 45 (0.9) | 7 (0.6) | |

| Histologic Type | |||

| Clear cell | 4430 (90.4) | 1011 (89.8) | .5005 |

| Non–clear cell | 468 (9.6) | 115 (10.2) | |

| Grade | |||

| Well differentiated | 161 (5.2) | 45 (8.9) | < .0001 |

| Moderately differentiated | 877 (28.5) | 185 (36.8) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 1382 (44) | 197 (39.2) | |

| Undifferentiated | 660 (21.4) | 76 (15.1) | |

| Tumor Size | |||

| ≥ 5 cm | 733 (17) | 246 (27.3) | < .0001 |

| > 5 cm | 3572 (83) | 654 (72.7) | |

| T Stage | |||

| T1 | 488 (29.9) | 156 (37.8) | .0056 |

| T2 | 473 (29) | 89 (21.5) | |

| T3 | 119 (7.3) | 24 (5.8) | |

| T4 | 541 (33.1) | 140 (33.9) | |

| T0/Tis | 11 (0.7) | 4 (1) | |

| N Stage | |||

| N0 | 2544 (68.4) | 549 (76.6) | < .0001 |

| N1 | 1173 (31.6) | 168 (23.4) | |

| Surgery Type | |||

| No nephrectomy | 1773 (36.3) | 696 (62.3) | < .0001 |

| Nephrectomy | 3105 (63.7) | 421 (37.7) |

Abbreviations: AI/AN = American Indian/Alaskan Native; API = Asian Pacific Islander; IQR = interquartile range.

Analysis of DSS by Age Group and Period

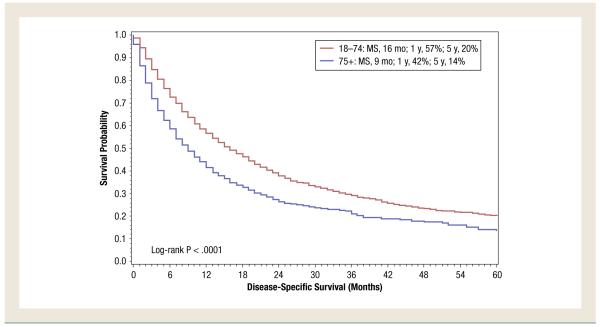

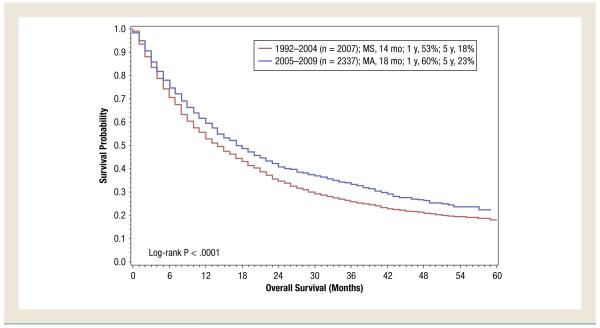

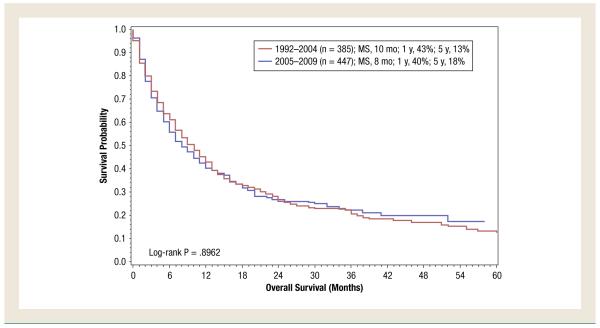

For the overall study period (1992-2009), DSS was shorter in patients aged ≥ 75 years compared with patients aged < 75 years (9 months vs. 16 months; P < .0001 (Figure 1). In patients aged 18 to 74 years, it was noted that DSS had improved in the targeted therapy era compared with the immunotherapy era (18 months for patients diagnosed from 2005 to 2009 vs. 14 months for patients diagnosed from 1992 to 2004; P < .0001) (Figure 2). However, in patients aged ≥ 75 years, no difference was noted (P = .90) (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Disease-Specific Survival of Patients With De Novo Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Based on Age. (MS = median survival)

Figure 2.

Disease-Specific Survival of Patients Aged 18 to 74 Years With De Novo Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated During the Cytokine Era (1992-2004) Compared With That of Patients Treated in the Targeted Therapy Era (2005-2009). (MS = median survival)

Figure 3.

Disease-Specific Survival of Patients Aged ≥ 75 Years With De Novo Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated During the Cytokine Era (1992-2004) Compared With That of Patients Treated in the Targeted Therapy Era (2005-2009). (MS = median survival)

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis

Several clinical and pathologic characteristics were associated with DSS on univariate analysis. The results of both univariate and multivariate analysis are detailed in Table 2. On univariate analysis, older age (≥ 75 years) and male sex were associated with shorter DSS (P = .0002 and P < .0001, respectively). Among pathologic characteristics, patients with poorly differentiated or undifferentiated tumors had inferior DSS compared with those with well-differentiated or moderately differentiated tumors, but no difference in DSS was noted among patients with clear cell or non–clear cell histologic type. Patients with node-positive disease had shorter DSS compared with patients with node-negative disease. Patients diagnosed during the targeted therapy era (2005-2009) had improved DSS relative to patients diagnosed during the cytokine era (1992-2004). Furthermore, cytoreductive nephrectomy was also associated with improved clinical outcome (P < .0001). On multivariate analysis, older age, female sex, diagnosis during the cytokine era, node-positive disease, and absence of cytoreductive nephrectomy were independent predictors of shortened DSS. Notably, because T stage was recorded as Tx for the majority of patients, this was omitted from the final multivariate analysis. However, in an exploratory multivariate analysis, Tx status served as an independent predictor of DSS.

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Age Group

| Variable | n (%) | Univariate |

Multivariate |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value | ||

| Age Group | |||||

| 18-74y | 4898 (81.3) | 1.00 (Reference) | — | — | — |

| 75+ y | 1126 (18.7) | 1.48 (1.38-1.59) | < .0001 | 1.18 (1.08-1.30) | .0002 |

| Age | |||||

| Mean (± SD)/median (IQR) | 63.3 (± 11.9)/63 (55-72) | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) | < .0001 | — | — |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 4069 (67.5) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — | — |

| Women | 1955 (32.5) | 1.15 (1.08-1.22) | < .0001 | 1.22 (1.14-1.31) | < .0001 |

| Year of Diagnosis | |||||

| 1992-2004 | 2773 (46) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — | — |

| 2005-2009 | 3251 (54) | 0.89 (0.84-0.94) | .0001 | 0.91 (0.85-0.98) | .0130 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 4376 (72.6) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — | |

| Black | 484 (8) | 1.18 (1.06-1.31) | .0027 | 1.00 (0.88-1.13) | .9562 |

| Hispanic white | 781 (13) | 1.02 (0.93-1.12) | .6740 | 0.95 (0.86-1.05) | .3291 |

| API | 307 (5.1) | 0.79 (0.69-0.91) | .0009 | 0.80 (0.68-0.93) | .0050 |

| AI/AN | 52 (0.9) | 1.04 (0.77-1.40) | .8014 | 1.17 (0.85-1.61) | .3335 |

| Unknown | 24 (0.4) | 0.74 (0.43-1.28) | .2828 | 0.94 (0.54-1.62) | .8203 |

| Histologic Type | |||||

| Clear cell | 5441 (90.3) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — | |

| Non–clear cell | 583 (9.7) | 0.97 (0.88-1.07) | .5657 | — | — |

| Grade | |||||

| Well differentiated | 206 (3.4) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — | |

| Moderately differentiated | 1062 (17.6) | 0.88 (0.74-1.06) | .1819 | 1.20 (0.98-1.49) | .0820 |

| Poorly differentiated | 1579 (26.2) | 1.02 (0.85-1.21) | .8358 | 1.50 (1.22-1.85) | .0001 |

| Undifferentiated | 736 (12.2) | 1.27 (1.06-1.53) | .0116 | 1.97 (1.58-2.45) | < .0001 |

| Unknown | 2441 (40.5) | 1.70 (1.44-2.02) | < .0001 | 1.37 (1.12-1.67) | .0019 |

| T Stage | |||||

| T1 | 644 (10.7) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — | |

| T2 | 562 (9.3) | 1.16 (1.00-1.35) | .0494 | — | — |

| T3 | 143 (2.4) | 1.27 (0.99-1.64) | .0582 | — | — |

| T4 | 681 (11.3) | 1.14 (0.99-1.31) | .0690 | — | — |

| T0/Tis | 15 (0.2) | 1.20 (0.57-2.54) | .6267 | — | — |

| TX | 3979 (66.1) | 1.48 (1.33-1.66) | < .0001 | ||

| N Stage | |||||

| N0 | 3093 (51.3) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — | |

| N1 | 1341 (22.3) | 1.81 (1.68-1.95) | < .0001 | 1.72 (1.58-1.87) | < .0001 |

| NX | 1590 (26.4) | 1.73 (1.62-1.86) | < .0001 | 1.26 (1.16-1.38) | < .0001 |

| Surgery Type | |||||

| No nephrectomy | 2469 (41) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — | |

| Nephrectomy | 3526 (58.5) | 0.39 (0.36-0.41) | < .0001 | 0.37 (0.34-0.41) | < .0001 |

| Unknown | 29 (0.5) | 0.61 (0.41-0.92) | .0172 | 0.48 (0.29-0.79) | .0037 |

Abbreviations: AI/AN = American Indian/Alaskan Native; API = Asian Pacific Islander; IQR = interquartile range.

Discussion

The results presented here provide support for our own institutional experience, suggesting that DSS in patients aged ≥ 75 years with mRCC may be shorter than DSS in patients aged < 75 years. A more provocative finding of our analysis suggests that although targeted therapy extends DSS for patients < 75 years, the same is not true for patients aged ≥ 75 years. Indeed, applying the same age cutoff of 75 years and comparing DSS during the cytokine era with DSS during the targeted era, only patients < 75 years were shown to have improved DSS since the advent of targeted therapies (ie, 2005-2009).

These findings are particularly compelling given that certain immune-based therapies (ie, IL-2) are typically perceived as being applicable to younger patients who have limited comorbidity. In the SELECT trial, a recent prospective evaluation of high-dose IL-2 in 120 patients with mRCC, no patient enrolled was > 70 years.8 In contrast, phase III studies evaluating targeted therapies have allowed a more heterogeneous array of patients. Several subset analyses have suggested minimal differences in safety and efficacy with targeted agents in older adults. For instance, in the RECORD-1 study comparing everolimus and placebo in patients with mRCC that had progressed on sunitinib and/or sorafenib (possibly also with previous bevacizumab or immunotherapy exposure), progression-free survival and overall survival were similar in patients aged ≥ 70 years.9 Several toxicities were more prevalent in older adults (peripheral edema, cough, rash, and diarrhea) regardless of the treatment arm (ie, everolimus or placebo), but otherwise the toxicity profiles were similar across age groups. In an expanded access program including 2504 patients with mRCC treated with sorafenib, similar overall survival was observed in 736 patients (29%) aged ≥ 70 years (compared with patients aged < 70 years).10 The most frequent grade ≥ 3 adverse events (hand-foot syndrome, hypertension, and fatigue) occurred at a similar frequency both above and below this age cutoff.

With results showing similar efficacy and safety in older adults treated with targeted therapies, it is challenging to infer why older adults treated in the era of targeted therapies do not have DSS rates comparable to those of their younger counterparts. One potential explanation is that older adults may not be offered or, alternatively, do not accept targeted therapies. Because the SEER data set does not include systemic therapy status, we were unable to adjust for this in the current study. In our aforementioned institutional experience, we observed that 70% of patients aged ≥ 75 years did not receive systemic therapy.5 In contrast, only 33.5% of patients aged < 75 years received no systemic therapy. The reasons for this are unclear; our analyses were limited by a lack of comorbidity data, and it is entirely possible that the older adults in our series were less able to withstand systemic treatment. Nonetheless, our experience represents 1 of the few published reports inclusive of those patients who have not received therapy. The International mRCC Database Consortium experience, for instance, provides valuable insight into outcomes for older adults. The data set, however, comes with the caveat that patients were fit enough to receive first-line therapy with a VEGF-directed agent (a requirement for inclusion).11 Similarly, prospective studies of targeted therapies all have rigorous eligibility criteria. In contrast, evidence suggests that patients with mRCC who do not meet standard eligibility criteria have significantly inferior outcomes.12 Other studies have assessed the relationship of age and clinical outcome, albeit using a much younger cutoff. Ku et al13 assessed clinicopathologic features and survival in a cohort of patients with mRCC ranging in age from 22 to 84 years. It was found that younger patients (specifically, those aged ≤ 40 years) had smaller tumors with lower clinical stage and lower Fuhrman grade. Despite these differences, younger patients were not found to have improved DSS on multivariate analysis.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. First, SEER does not report comorbidity data. The known association between increasing age and extent of comorbidity could possibly confound observations related to survival in older adults.14 However, the survival analyses conducted by us focused on disease-specific and not overall survival. Second, only the stage at initial diagnosis in noted in the SEER registry. As such, only patients with de novo metastatic disease would be included in the registry. Both Heng and Motzer risk stratification criteria consider a time from diagnosis to initiation of systemic therapy < 1 year to be an adverse prognostic factor.11,15 Using the same risk stratification tools, patients with de novo metastatic disease inherently have intermediate- or poor-risk disease. Although the constraints of the SEER data set inherently limited our analyses to de novo disease, it is challenging to envision what would lead to discordance in age-related outcomes by risk group. A third limitation is the aforementioned lack of data related to systemic therapies received. Although the terms cytokine era and targeted therapy era pertain to periods when these drugs were predominantly used, the actual practice patterns cannot be confirmed. Therefore, as previously noted, statistical adjustment for receipt of systemic treatment was not possible. Notably, Shek et al16 published an assessment of clinical outcomes for patients with RCC housed in the California Cancer Registry. In their study, survival during the cytokine era (defined as 1998-2003) was compared with survival during the targeted therapy era (defined as 2004-2007). The definition we applied for the targeted therapy era (2005-2009) was much more likely to account for use of these agents, which were approved in late 2005 onward.

There are several limitations and shortcomings of SEER analyses that permeate this study and others using this data set. For instance, coding reliability is variable within SEER. A diagnosis of kidney cancer may encompass both RCC and upper urothelial tract tumors. To account for this, we have limited our analyses to patients in whom a specific histologic type consistent with RCC was noted (ie, clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe). A recent study by Shuch et al17 suggested that these diagnoses were recorded in SEER with substantial precision. Missing data are another issue in SEER, with several variables relevant to RCC not recorded. For instance, although tumors are classified as well-differentiated, poorly differentiated, and so on, there is no specific designation for Furhman grading in the database. Patient migration also complicates assessments of the SEER database. If patients move in and out of geographic regions encompassed within SEER, their initial capture and follow-up may be compromised. Further issues in SEER analyses are detailed in an eloquent article by Yu et al.18

Despite these limitations, the data presented here serve as a compelling rationale to further assess our current treatment paradigm for older adults with mRCC. In addition to finding shorter DSS among patients aged ≥ 75 years, we observed that (in contrast to younger adults) clinical outcome did not improve for older adults in the era of targeted therapy. Future research should look toward accurately characterizing patterns of care in older adults in large series. If these data highlight that older adults are consistently receiving less treatment, it would be critical, albeit challenging, to ascertain whether this was the result of competing risks (ie, frailty, comorbidity, and so on) as opposed to practitioner bias. In parallel, prospective studies assessing safety and tolerability of novel targeted therapies for mRCC may be warranted, including investigations of pharmacokinetics and relevant biomarkers. There are several examples of biomarkers that cross over as putative markers of both aging and treatment efficacy. For instance, elevated IL-6 has been associated both with increasing age and clinical outcome with the VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitor pazopanib.19,20 Outside laboratory-based biomarkers, use of novel clinical tools may help identify appropriate candidates for systemic therapy. As 1 prominent example, the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment includes a battery of brief clinical inventories that allow for a functional assessment of older adults. Indeed, the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment is being assessed prospectively in a wide array of cooperative group studies coordinated by the Alliance.21 These proposed efforts to optimize treatment of older adults with mRCC will certainly require substantial resources. However, unless such efforts are undertaken, alarming trends for clinical outcome in older adults with mRCC may persist.

Clinical Practice Points.

Preliminary data from our institution (consistent with other recent studies) suggest that older adults with mRCC (specifically, patients aged ≥ 75 years) have inferior DSS compared with younger cohorts.

From the SEER data set, we analyzed 6024 patients with mRCC and documented clear cell, papillary, or chromophobe histologic type.

DSS was shorter in patients aged ≥ 75 years compared with patients aged < 75 years (9 vs. 16 months; P < .0001).

In patients 18 to 74 years, DSS was superior in the targeted therapy era compared with the cytokine era (P < .0001). However, in patients ≥ 75 years, no difference in DSS was noted between these periods (P = .90).

Further research is necessary to determine why older adults do not appear to have the improvement in DSS during the targeted therapy area relative to the cytokine era, as do their younger counterparts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH, K12 2K12CA001727-16A1 (Dr Pal).

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors have stated that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fyfe G, Fisher RI, Rosenberg SA, et al. Results of treatment of 255 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received high-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:688–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, et al. Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:289–96. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pal SK, Kortylewski M, Yu H, et al. Breaking through a plateau in renal cell carcinoma therapeutics: development and incorporation of biomarkers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:3115–25. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khambati H, Choueiri TK, Kollmannsberger CK, et al. Efficacy of targeted drug therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the elderly patient population. Paper presented at: 2011 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium; Orlando, FL. February 17-19, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pal SK, Hsu J, Hsu S, et al. Impact of age on treatment trends and clinical outcome in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Geriatric Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2012.11.001. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDermott DF, Atkins MB. Interleukin-2 therapy of metastatic renal cell carcinoma—predictors of response. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:583–7. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Health & Human Services [Accessed: March 24, 2010];Approval letter for sorafenib. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/appletter/2005/021923ltr.pdf.

- 8.McDermott DF, Ghebremichael MS, Signoretti S, et al. The high-dose aldesleukin (HD IL-2) “SELECT” trial in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4514. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porta C, Calvo E, Climent MA, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus in elderly patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an exploratory analysis of the outcomes of elderly patients in the RECORD-1 trial. Eur Urol. 2012;61:826–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.12.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bukowski RM, Stadler WM, McDermott DF, et al. Safety and efficacy of sorafenib in elderly patients treated in the North American advanced renal cell carcinoma sorafenib expanded access program. Oncology. 2010;78:340–7. doi: 10.1159/000320223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heng DYC, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor. Targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5794–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heng DYC, Choueiri TK, Lee J-L, et al. [Accessed: April 24, 2013];An in-depth multicentered population-based analysis of outcomes of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) that do not meet eligibility criteria for clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2012 30(suppl) abstract 4536. Available at: http://www.asco.org. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ku JH, Moon KC, Kwak C, et al. Disease-specific survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma: an audit of a large series from Korea. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:110–4. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piccirillo JF, Tierney RM, Costas I, et al. Prognostic importance of comorbidity in a hospital-based cancer registry. JAMA. 2004;291:2441–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.20.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Mazumdar M. Prognostic factors for survival of patients with stage IV renal cell carcinoma: Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6302S–3S. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-040031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shek D, Tomlinson B, Brown M, et al. Epidemiologic trends in renal cell carcinoma in the cytokine and post-cytokine eras: a registry analysis of 28,252 patients. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2012;10:93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shuch B, Hofmann JN, Merino MJ, et al. Pathologic validation of renal cell carcinoma histology in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Urol Oncol. 2013 Feb 29; doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.08.011. [E pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu JB, Gross CP, Wilson LD, et al. NCI SEER public-use data: applications and limitations in oncology research. Oncol (Williston Park) 2009;23:288–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Preacher KJ, MacCallum RC, et al. Chronic stress and age-related increases in the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9090–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531903100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran HT, Liu Y, Zurita AJ, et al. Prognostic or predictive plasma cytokines and angiogenic factors for patients treated with pazopanib for metastatic renal-cell cancer: a retrospective analysis of phase 2 and phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:827–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurria A, Cirrincione CT, Muss HB, et al. Implementing a geriatric assessment in cooperative group clinical cancer trials: CALGB 360401. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1290–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]