Abstract

Background

The Bridle procedure restores active ankle dorsiflexion through a tri-tendon anastamosis of the tibialis posterior, transferred to the dorsum of the foot, with the peroneus longus and tibialis anterior tendon. Inter-segmental foot motion after the Bridle procedure has not been measured. The purpose of this study is to report kinetic and kinematic variables during walking and heel rise in patients after the Bridle procedure.

Methods

18 Bridle and 10 control participants were studied. Walking and heel rise kinetic and kinematic variables were collected and compared using an ANOVA.

Findings

During walking the Bridle group, compared with controls, had reduced ankle power at push off [2.3 (SD 0.7) W/kg, 3.4 (SD 0.6) W/kg, respectively, P<.01], less hallux extension during swing [−13 (SD 7)°, 15 (SD6)°, respectively, P<.01] and slightly less ankle dorsiflexion during swing [6 (SD4)°, 9 (SD 2)°, respectively, P=.03]. During heel rise the Bridle group had 4 (SD 6)° of forefoot on hindfoot dorsiflexion compared to 8 (SD 3)° of plantarflexion in the controls (P<.01).

Interpretation

This study provides evidence that the Bridle procedure restores the majority of dorsiflexion motion during swing. However, plantarflexor function during push off and hallux extension during swing were reduced during walking in the Bridle group. Abnormal mid-tarsal joint motion, forefoot on hindfoot dorsiflexion instead of plantarflexion, was identified in the Bridle group during the more challenging heel rise task. Intervention after the Bridle procedure must maximize ankle plantarflexor function and midfoot motion should be examined during challenging tasks.

1. Introduction

Traumatic lesions to the sciatic or common fibular nerve result in loss of function of the anterior compartment leg muscles and variable loss of lateral compartment leg muscles that produce ankle dorsiflexion and eversion. Typically, all of the posterior compartment muscles are spared. Loss of ankle dorsiflexor muscle function results in a plantarflexed position of the ankle (drop foot) during the swing phase of walking and at initial ground contact, reducing function and increasing the risk of falling. The modified Bridle procedure, an ankle dorsiflexion restorative surgery, is a tri-tendon anastamosis in which the tibialis posterior muscle is transferred through the interosseous membrane to the anterior aspect of the ankle. The tibialis posterior tendon is then anastamosed with the tibialis anterior and peroneus longus tendons and the tri-tendon anastamosis is inserted into the 2nd cuneiform. The tri-tendon anastomosis between the peroneus longus and the anterior and posterior tibialis tendons creates a tensioned “bridle” to provide dorsiflexion as well as medial-lateral stability to the hindfoot (McCall et al. 1991; Gellman et al. 2002; Rodriguez 1992).

Previous research has shown primarily good to excellent outcomes after the Bridle procedure or similar tibialis posterior tendon transfer surgery in the majority of patients (Yeap et al. 2001; McCall et al. 1991; Vigasio et al. 2008; Steinau et al. 2011; Rodriguez 1992). Active dorsiflexion motion is restored and generally patients no longer require use of an ankle brace to prevent foot drop during walking (Hove, Nilsen 1998; Rath et al. 2010; Bibbo et al. 2011; Prahinski et al. 1996; Steinau et al. 2011; Yeap et al. 2001; Mizel et al. 1999; Vigasio et al. 2008; Steinau et al. 2011; Rodriguez 1992; Vigasio et al. 2008). However, there is concern that loss of the normal function of the tibialis posterior muscle and tendon, which helps support the arch, adduct the forefoot and invert the hindfoot, may result in an increased risk of developing changes in foot and ankle kinematics similar to individuals with tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction; increased calcaneal eversion, decreased plantarflexion of the forefoot, and loss of the arch height (Tome et al. 2006; Ness et al. 2008; Neville et al. 2010).

To date there has been no kinetic and kinematic assessment of inter-segmental foot and ankle motion during walking or the challenging heel rise task in patients after the Bridle procedure. Follow up studies of individuals who have undergone a Bridle procedure have employed visual appraisal and plantar pressure maps to assess changes in alignment (Yeap et al. 2001; Vigasio et al. 2008; Vertullo, Nunley 2002; Steinau et al. 2011; Mizel et al. 1999; McCall et al. 1991). Using visual appraisal and plantar pressure assessment 6% to 30% of individuals in studies measuring plantar pressure had an increase in medial plantar pressure and 8% to 19% of individuals in studies assessing alignment had an increase in calcaneal valgus or other alignment associated with a flat foot (Yeap et al. 2001; Mizel et al. 1999; Vertullo, Nunley 2002; Vigasio et al. 2008).

We believe kinetic and kinematic assessment is critical to understand the movement stress imposed on the foot after surgery, provide the medical team and patient with quantified surgical outcomes, and identify an area in which additional physical therapy intervention may improve long term patient outcomes. The purpose of this study is to assess the kinetic and kinematic analysis of walking and a heel rise task in patients at least one year post Bridle surgery.

2. Methods

2.1 Study design overview

This was a retrospective cohort study. A total of 28 participants were recruited and signed the consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board. Eighteen participants underwent the Bridle procedure as treatment for traumatic foot drop. Ten participants were controls that were matched for age, weight, and sex to the Bridle participants.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients were identified retrospectively through a database query of surgical cases performed by two fellowship-trained foot and ankle surgeons. Patients undergoing a deep tendon transfer were identified by current procedural terminology codes (CPT 27691). Only patients undergoing a Bridle tibialis posterior tendon transfer procedure were considered for this study and patients undergoing any other type of tendon transfer procedure were excluded. We contacted individuals who had received the Bridle procedure between the dates of July 2005 and September 2010. Participants in the Bridle procedure group were included if they had drop foot as a result of trauma and were at least one year post surgery. Individuals with a foot drop resulting from other etiologies were excluded. Participants in the control group had no recent history of foot or ankle injury with pain free, normal lower extremity function. Control participants were assigned an involved side based on the involved side of the Bridle subject for whom they matched. We excluded individuals from the Bridle and control groups if they had a neuromuscular disease, used an assistive device prior to their injury, or were non-ambulatory and unable to complete the tasks required for study participation.

2.3. Surgical technique and Post-operative Management

All Bridle participants failed conservative treatments including brace wear and activity modification and/or surgical interventions to assist with fibular nerve function return. The Bridle procedure was technically performed as described by Rodriguez (Rodriguez 1992). A gastroc-soleus lengthening was performed through an incision on the posterior medial calf on 14 of 18 patients who demonstrated a lack of passive ankle joint dorsiflexion of at least 5 degrees with the knee in extension.

Briefly, the tibialis posterior tendon was detached from its insertion on the navicular and transferred around posterior to the tibia and through the interosseus membrane into the anterior compartment of the lower leg. On the lateral aspect of the leg, the peroneus longus tendon was transected in the distal third of the leg and the proximal end was sutured into the peroneus brevis if the lateral compartment muscles were functional. The distal end of the peroneus longus tendon was transferred to the anterior compartment alongside the tibialis posterior and tibialis anterior tendons. The free distal end of the tibialis posterior tendon was passed through a slit in the tibialis anterior tendon and a slit in the peroneus longus tendon, and then passed under the extensor retinaculum of the ankle and inserted into to the 2nd cuneiform. The tibialis posterior tendon was then tensioned to about 80% of its excursion while holding the ankle in neutral and the tendon was fixed in the 2nd cuneiform.

Post-operatively, patients were immobilized in a cast and non-weightbearing for 2 weeks and then toe-touch weightbearing in a cast for four weeks. At 6 weeks post-operative, patients were placed into a removable walker boot and allowed to progress to full weightbearing as tolerated. Physical therapy was begun for re-education of the tibialis posterior tendon transfer with active and active assisted dorsiflexion and active plantar flexion. A night splint was worn and passive ankle joint plantarflexion was avoided until 3 months post-operative to prevent premature stretching of the transfer. As swelling improved, a custom molded AFO was fabricated to be worn in an athletic shoe to allow earlier discontinuation of the walker boot. The custom AFO or walker boot was used until at least 3 months post-operative or until strength allowed discontinuation of the brace.

2.3 Temporal, kinematic and kinetic data collection

Temporal and kinematic data of the involved side for the thigh, shank, and foot were captured with an 8-camera 200 Hz Vicon motion analysis system (Vicon MX, Los Angeles, California, USA). Ten millimeter reflective markers were attached to the skin with double sided tape or to thermoplastic plates for the thigh, shank, hindfoot, and great toe. Markers for the thigh where placed on the greater trochanter, medial and lateral femoral condyles, and four markers were mounted to a plate and secured to the distal-lateral thigh. The shank markers were located on the fibular head, tibial tuberosity, medial and lateral malleoli, and four markers were mounted to a plate and secured to the distal-lateral shank. Marker placement and segment models for the hindfoot, forefoot and hallux followed the modified Oxford multi-segmental foot model described by Carson (Carson et al. 2001). The hindfoot markers were located at the sustentaculum tali, peroneal trochlea, and two markers were mounted to a plate that was aligned with the bisection of the posterior calcaneus. The forefoot markers were located at the base and head of the first and fifth metatarsals and a marker between the second and third metatarsal heads. The hallux was defined by a three-marker plate that was aligned with the long axis of the proximal phalanx. The multi-segmented foot model was built in Visual3D software (C-Motion Inc. Germantown, MD, USA). The landmarks along with projected or virtual markers were used to define the segment anatomical reference frames. The zero angles for all inter-segmental motions represent the parallel orientation of the axes. The 0° angle of the forefoot on hindfoot and hallux on forefoot motion in the sagittal plane (dorsiflexion/plantarflexion, extension/flexion) represents the angle between the segments when each segment is referenced with a line parallel to the floor during the standing calibration trial. The 0° position of the hindfoot on shank in the frontal plane (inversion/eversion) represents the angle between the segments using anatomical landmarks to approximate the long axis of the segment (Appendix A). Kinetic data were collected simultaneously using a Bertec K80301 force platform (Bertec Corporation, Columbus, OH, USA).

Walking kinetic and kinematic data were collected while participants walked barefoot at their self-selected speed. Participants were provided feedback with instruction to walk faster or slower in order to closely replicate the walking speed of the first trial and minimize trial to trial walking speed variability. Walking speed was calculated in Visual 3D for the stride in which the foot hit the force plate (i.e. right stride when the left foot was on the force plate). Five trials for which the involved side stepped on the force platform were analyzed for each individual. We selected and limited the temporal, kinetic, and kinematic variables chosen for group comparison based on an a priori hypothesis. We believed that loss of the tibialis posterior muscle and tendon as a medial longitudinal arch stabilizer, ankle plantarflexor, and calcaneal inverter and the addition of an intervention to increase dorsiflexion range of motion would result in the following during walking; 1) forefoot on hindfoot dorsiflexion during terminal stance, 3) a loss of ankle plantarflexor power at push off, 3) an increase in peak hindfoot on shank dorsiflexion range of motion during the stance phase, and 4) increase in hindfoot on shank eversion during stance phase. Additionally, we aimed to assess the impact of the Bridle procedure on the swing phase of gait and measured peak hindfoot on shank dorsiflexion and hallux extension at 50% of swing phase.

Temporal, kinetic, and kinematic data were also collected during a barefoot single leg heel rise task. The primary goal of the heel rise task was to provide a challenging activity that would be sensitive to changes in foot function as a result of the surgical intervention. Participants were instructed to complete 20 unilateral heel rises with the knee extended, using hands for balance only. Twenty repetitions were chosen in order to maximize the potential of measuring changes in movement quality/quantity that might become more obvious with fatigue. Heel rise speed was calculated within the kinematic processing software. Distance was calculated as the total distance traveled during the heel rise and return along the vertical axis, divided by the time it took to complete the heel rise task. In addition to the key variables described above, knee flexion was measured during the heel rise task as this is a common compensatory strategy for plantarflexor weakness. For hindfoot on shank plantarflexion, forefoot on hindfoot dorsiflexion/plantarflexion, hindfoot on shank inversion, and knee flexion variables, the value at peak height of the heel rise task was extracted. The three trials with the highest plantarflexor power production were selected for the analysis and the variables of interest for these three trials were averaged.

2.4 Statistical analyses

Subject characteristics between groups were compared using a one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables (age, height, and weight) and Chi-square for discrete variables (sex, race). Walking temporal and kinematic variables were analyzed using an ANOVA. Ankle power during walking was analyzed using an ANCOVA with walking speed as a co-variate. Heel rise temporal, kinetic, and kinematic variables were analyzed using an ANOVA. SPSS Statistics version 19 was used for all statistical analyses (SPSS Statistics Inc., Chicago, USA). A P value of ≤.05 was considered significant for all comparisons.

3. Results

3.1 Subject characteristics

Forty-three individuals underwent the Bridle procedure between 2005 and 2011. We were able to contact 32 individuals and 18 consented to participate in the study [age=40 (SD18) yrs, weight=97 (SD 23) kg, 13 males and 5 females]. (Table 1) On average, the Bridle procedure had been performed 1.9 (SD 0.8) years prior to testing. All 18 participants had a drop foot as a result of a traumatic injury. In 11 participants the injury was isolated to the knee, in 2 participants the injury was isolated to the hip, and in 6 participants their original injury was not isolated to one area of the lower extremity. Ten controls consented to participate [age=44 (SD 22) yrs, weight=93 (SD 16) kg, 7 males and 3 females]. There were no significant differences between groups in any of the demographic variables.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Bridle (n=18) | Controls (n=10) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 40 (18) | 44 (22) | .60 |

| Sex (Male/Female) | 13/5 | 7/3 | .90 |

| Height (m) | 1.74 (0.09) | 1.75 (0.09) | .76 |

| Weight (kg) | 97 (23) | 93 (16) | .62 |

| Race (Caucasian/African American) | 17/1 | 10/0 | .45 |

| Involved Side | 10 Right 8 Left |

- |

Values are given as the mean (standard deviation) or number.

3.2 Temporal, kinetics and kinematics for walking

The Bridle group walked slower than the control group during kinetic and kinematic data collection [1.1 (SD 0.2) m/sec, 1.3 (SD 0.2) m/sec, respectively, P=.01].

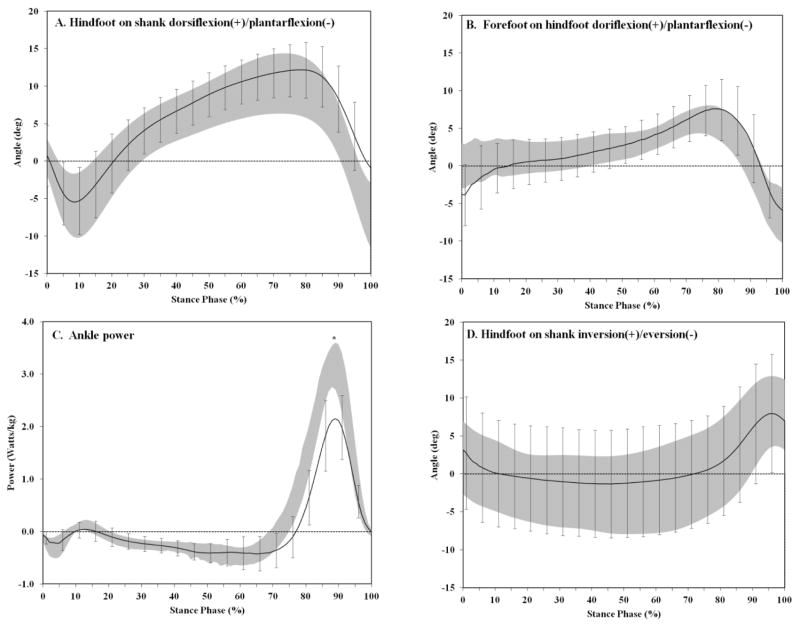

During the stance phase of walking, there were no differences in peak forefoot on hindfoot dorsiflexion, hindfoot on shank eversion, or hindfoot on shank dorsiflexion between the Bridle and control groups (P>.05). (Table 2, Figure 1) The Bridle group had loss of ankle plantarflexion power at push off [2.3 (SD 0.7) W/kg] compared to controls [3.4 (SD 0.6) W/kg, P<.01].

Table 2.

Walking and heel rise kinematics and kinetics

| Bridle (n=18) | Control (n=10) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Walking: Stance Phase Kinematics and Kinetics | |||

| Walking Speed (m/sec) | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.2) | .01 |

| Peak Forefoot on Hindfoot Dorsiflexion (+) (deg) | 8 (3) | 7 (3) | .44 |

| Peak Ankle Power (Watts/kg) | 2.3 (0.7) | 3.4 (0.6) | <.01 |

| Peak Hindfoot Eversion (−) (deg) | −3 (7) | −4 (4) | .50 |

| Peak Hindfoot on Shank Dorsiflexion (+) (deg) | 13 (4) | 12 (4) | .63 |

| Walking: Swing Phase Kinematics | |||

| Peak Ankle Dorsiflexion (+)(deg) | 6 (4) | 9 (2) | .03 |

| Peak Hallux Extension (+) (deg) | −13 (7) | 15 (6) | <.01 |

| Heel Rise: Kinematics and Kinetics | |||

| Heel rise speed (cm/sec) | 10 (5) | 17 (5) | <.01 |

| Peak Ankle Plantarflexion(−)(deg) | 0 (8) | −15 (10) | <.01 |

| Forefoot on Hindfoot Dorsiflexion(+)/Plantarflexion(−)at peak of heel rise (deg) | 4 (6) | −8 (3) | <.01 |

| Peak Ankle Power (Watts/kg) | 1.3 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.7) | <.01 |

| Hindfoot on Shank Inversion (+)at peak of heel rise (deg) | 4 (7) | 2 (8) | .53 |

| Knee Flexion(−) at peak of heel rise (deg) | −19 (10) | −10 (5) | .01 |

Values are given as the mean (standard deviation).

Figure 1.

Walking stance phase kinematics and kinetics summarized for (A) talocrural dorsiflexion/plantarflexion, (B) Forefoot on hindfoot dorsiflexion/plantarflexion, (C) Ankle power, and (D) Calcaneal inversion/eversion. Shaded band represents the mean ± 1 standard deviation for the control subjects. Solid line is the mean ± 1 standard deviation bars for the Bridle subjects.

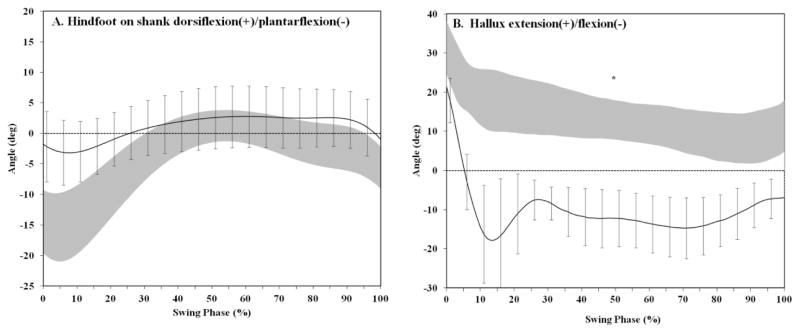

During swing there was a small decrease in peak hindfoot on shank dorsiflexion in the Bridle group compared to Controls (Bridle=6 (SD 4)°, Controls=9 (SD 2)°, P=.03). In addition, the hallux was flexed in the Bridle group [−13 (SD 7)°] compared to extended in controls [15 (SD 6)°, P<.01]. (Table 2, Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Walking swing phase kinematics summarized for (A) talocrural dorsiflexion/plantarflexion and (B) hallux extension/flexion. X-axis: 0=toe off, 100=heel strike of the same side. Shaded band represents the mean ± 1 standard deviation for the control subjects. Solid line is the mean ± 1 standard deviation bars for the Bridle subjects.

3.3 Temporal, kinetics, and kinematics for the heel rise task

Heel rise was completed more slowly in the Bridle group compared to controls [10 (SD 5) cm/sec versus 17 (SD 5) cm/sec respectively, P<.01].(Table 2) Twenty repetitions were completed in 12 of 18 Bridle group participants and 8 of 10 control group participants. The highest 3 values of plantarflexor power used in the kinematic and kinetic analysis never occurred within the first 5 repetitions for any participant. The highest 3 plantarflexor values occurred in repetitions 6–10 for 33% and 30% of the Bridle and control participants, in repetitions 11–15 for 33% and 20% of Bridle and control participants, and in repetitions 16–20 in 33% and 50% of Bridle and control participants.

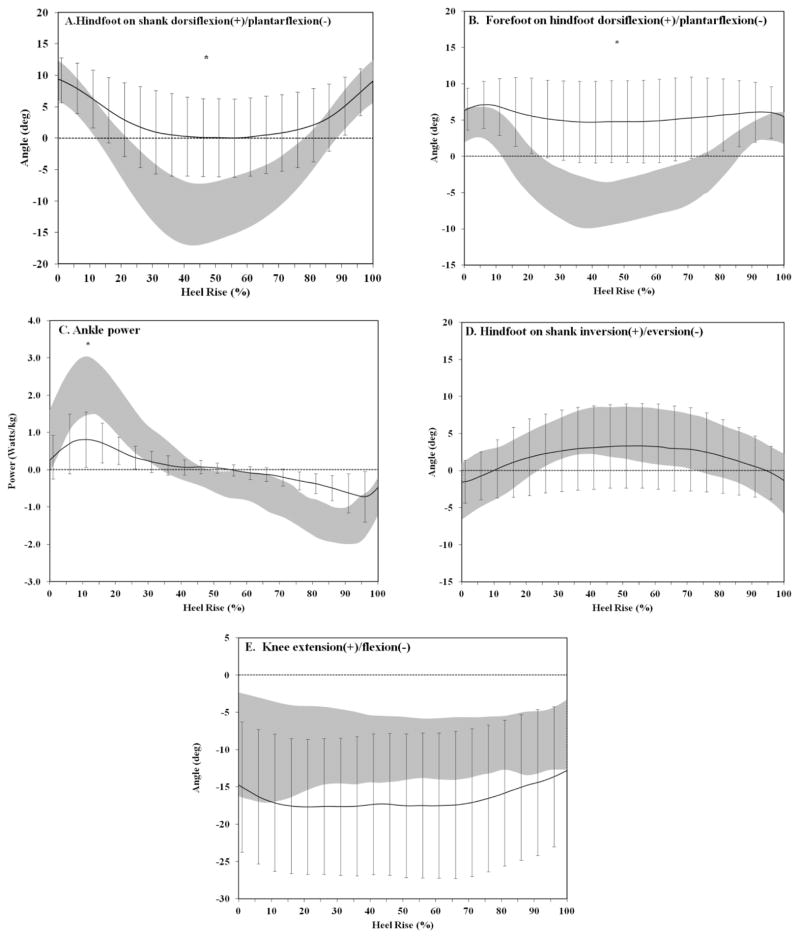

The Bridle group completed the heel rise task with less hindfoot on shank plantarflexion [Bridle=0 (SD 8)°, Control=−15 (SD 10)°, P<.01], with forefoot on hindfoot dorsiflexion (Bridle= 4 (SD 6)°), instead of plantarflexion [Control= −8 (SD 3)°, P<.01], reduced ankle power [Bridle= 1.3 (SD0.7) Watts/kg, Control= 2.6 (SD 0.7 Watts/kg, P<.01] and with greater knee flexion [Bridle= −19 (SD 10)°, Control= −10 (SD 5)°, P=.01].(Table 2 and Figure 3) Despite clear instructions to maintain a straight knee during the heel rise task, only 5 of 18 Bridle participants completed the heel rise task with peak knee flexion values comparable to the control group. There was no difference between groups in the amount of hindfoot on shank inversion.

Figure 3.

Heel rise kinematics and kinetics summarized for (A) hindfoot on shank dorsiflexion/plantarflexion, (B) forefoot on hindfoot dorsiflexion/plantarflexion, (C) hindfoot on shank power, (D) hindfoot on shank inversion/eversion, and (E) knee extension/flexion. Shaded band represents the mean ± 1 standard deviation for the control subjects. Solid line is the mean ± 1 standard

4. Discussion

This study employed a multi-segmental kinematic foot model in conjunction with a thigh and shank model to investigate the temporal, kinetic and kinematic variables during walking and a heel rise task in individuals following a Bridle procedure. Walking kinematic analysis indicates the surgical intervention was successful in restoring most all of active dorsiflexion during swing without abnormal midfoot motion during stance phase of walking. However, the Bridle group had reduced plantarflexor power at push off and there remained insufficient control of hallux extension during the swing phase of walking compared to controls. During the more demanding heel rise task, peak ankle power was significantly reduced and the kinematic motion analysis indicated abnormal midfoot motion in the Bridle group with the forefoot unable to plantarflex on the hindfoot as measured in the control group. The lack of mid-foot stability and decreased ankle power may be explained by the loss of the tibialis posterior and peroneus longus tendons and muscles as a dynamic stabilizer of the mid foot in conjunction with the gastrocnemius-soleus lengthening and potentially insufficient rehabilitation.

Walking kinematic analysis provided three important insights regarding Bridle procedure outcomes. First, the Bridle procedure was successful in restoring most all of the active hindfoot on shank dorsiflexion during the swing phase of walking. The Bridle group, on average, had 6° of dorsiflexion beyond the standardized position of the foot in the calibration trial. Although the difference between controls and Bridle participants was statistically significant, we do not believe the 3° difference was clinically meaningful. Second, the Bridle procedure does not include a component to restore active hallux and toe extension. The lack of hallux extension was evident during swing phase of walking. Together, the restoration of active hindfoot on shank dorsiflexion with the inability to control hallux extension matched patient reported outcomes. The Bridle group reported the ability to discontinue use of their ankle foot orthosis but the continued need for caution, particularly when barefoot or in low profile shoes (e.g. flip-flop sandals), to avoid catching the toe during walking and increasing the risk of falls. Third, there is no indication of a lack of hindfoot inversion during walking that may contribute to or indicate potential of developing the abnormal motions associated with tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction.

Walking kinematic analysis in the Bridle group indicates plantarflexion range of motion of up to 5°, however, in the loaded heel rise task there is an inability to actively plantarflex the ankle past neutral and the reduction in ankle plantarflexor power is evident in both the walking and heel rise tasks. In addition the Bridle participants often used knee flexion to assist in raising the heel off the ground. We believe this represents residual weakness of the plantarflexors, on average, 2 years after surgery. Although previous reports measuring plantarflexor strength using manual muscle testing have reported no deficits (Mizel et al. 1999; Yeap et al. 2001), quantitative dynamometry evaluation of plantarflexor strength consistently finds a reduction in plantarflexor muscle function after the Bridle procedure.(Yeap et al. 2001; Steinau et al. 2011) There are a number of potential contributors to the residual reduction in plantarflexor function. Certainly the loss of the tibialis posterior muscle and the reattachment of the fibularis brevis muscle belly to the fibularis longus muscle result in a loss of overall plantarflexor power production capability. Additionally, the Bridle procedure is also often accompanied by a gastrocnemius-soleus muscle/tendon lengthening procedure to increase dorsiflexion range of motion and may contribute to residual plantarflexor weakness. Although, there is evidence to support return of plantarflexor strength to pre-operative levels within 7 months after a gastrocnemius/soleus lengthening procedure,(Mueller et al. 2003) comparison to control and contra-lateral side plantarflexor strength measures indicate residual weakness up to 18 month after the procedure.(Chimera et al. 2010; Sammarco et al. 2006) Finally, the lack of standardized, aggressive physical therapy intervention may have limited the potential to reverse the plantarflexor power deficits and is an important area for future study.

The heel rise task provides new information about changes in dynamic foot function during a more foot specific and challenging activity. In Bridle participants the forefoot fails to plantarflex on the hindfoot, remaining in a dorsiflexed position throughout the heel rise task. The inability to plantarflex the forefoot on the hindfoot may be attributed to the transfer of the tibialis posterior tendon and the loss of the peroneus longus as dynamic stabilizers of the medial mid foot and longitudinal arch. These inferences require additional research to further examine other factors that may contribute to the loss of midfoot function including the role of the residual extrinsic and intrinsic foot muscles.

The kinematic analysis of foot motion across these two tasks indicated that abnormal foot motion is not measured until the foot is required to perform more challenging tasks. Kinematic analysis of walking and heel rise has not previously been tested in those who have received the modified Bridle procedure. However, foot motion has been examined during walking in individuals who have tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction, a potentially analogous anatomical deficit in which the tibialis posterior tendon is inflamed, lengthened, or torn and no longer able to provide stability to the arch and contribute to dynamic function of the foot and ankle. In those with tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction there is consistent evidence of increased hindfoot eversion, more dorsiflexion of the forefoot on the hindfoot, forefoot abduction, and a lower arch during the less challenging task of walking.(Neville et al. 2010; Johnson, Harris 1997) Our study indicates that the Bridle procedure does not result in the severity of dysfunction experienced in those with Stage II or higher tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction. However, dysfunction is still prominent if those with the modified Bridle procedure attempt more vigorous activities. Additional research is needed to assess whether foot motion dysfunction progresses over time, particularly in active individuals.

There are a number of limitations associated with this study that should be considered when interpreting these results. The average follow-up time of almost 2 years was sufficient to measure the almost complete restoration of active dorsiflexion during swing but is likely not long enough to capture potential complications or further strength and functional improvements that may occur with a longer follow up time. The retrospective nature of the study design does not allow us to quantify the improvements in function provided by the Bridle procedure but only to compare current levels of function to matched controls. The individuals receiving the Bridle procedure had diverse medical and surgical histories that may impact and mitigate their functional recovery. The small sample size prevented us from examining the impact of these variables (e.g. isolated knee trauma versus multi-level trauma, Bridle procedure plus tendo-achilles procedure versus, Bridle procedure only).

The heel rise task was a unique and novel kinematic approach that allowed identification of differences in foot motion quality and quantity that were not present during the traditional walking task. Use of the heel rise task for future research may consider standardizing the procedure to allow comparison of the number of heel rise repetitions performed to normative data available for the heel rise task (Jan et al. 2005; Lunsford, Perry 1995). Inclusion of a bilateral heel rise to establish a maximum heel rise height as a comparison for the single leg task would allow an assessment of strength. When the single leg heel rise task is used for strength assessment, knee flexion during the task must be minimized to eliminate this compensatory strategy for elevating the heel off the ground. It is also important that future work using the heel rise task critically assess the number of repetitions required to address the study question. Twenty repetitions was not likely necessary to obtain the critical information in this post-surgical group. Finally, the position of the hindfoot, forefoot and hallux segments in the sagittal plane are referenced to the ground in standing. These models allow an estimate of angular excursion between segments however a comparison of absolute joint positions between groups is not possible.

5. Conclusion

This study provides evidence that the Bridle procedure returned almost all of the dorsiflexion required during the swing phase of walking. However, ankle plantarflexor muscle function was reduced during walking and heel rise in those with the Bridle procedure compared to controls. The heel rise task also identified that the forefoot was unable to plantarflex on the hindfoot, indicating impaired function at the mid-tarsal joint. Rehabilitation interventions after the Bridle procedure must include an aggressive program to maximize plantarflexor function, the midfoot should be closely monitored for dysfunction and foot orthoses to support the mid-tarsal joint may be indicated in some individuals

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Midwest Stone Institute, K12 HD055931, K30 RR022251

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Robert Deusinger PT, PhD and Melanie Koleini MS for their assistance in kinematic and kinetic data collection methods.

We acknowledge funding support from the Midwest Stone Institute, and the National Institutes of Health: K12 HD055931, K30 RR022251.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- McCall RE, Frederick HA, McCluskey GM, Riordan DC. The Bridle procedure: a new treatment for equinus and equinovarus deformities in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1991;11:83–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellman RE, Anderson RB, Davys HJ. Bridle Posterior Tibial Tendon Transfer. In: Kitaoka HB, editor. Foot Ankle. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2002. pp. 597–613. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez R. The Bridle procedure in the treatment of paralysis of the foot. Foot Ankle. 1992;13:63–69. doi: 10.1177/107110079201300203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeap JS, Birch R, Singh D. Long-term results of tibialis posterior tendon transfer for drop-foot. Int Orthop. 2001;25:114–118. doi: 10.1007/s002640100229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigasio A, Marcoccio I, Patelli A, Mattiuzzo V, Prestini G. New tendon transfer for correction of drop-foot in common peroneal nerve palsy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1454–1466. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0249-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinau HU, Tofaute A, Huellmann K, Goertz O, Lehnhardt M, Kammler J, et al. Tendon transfers for drop foot correction: long-term results including quality of life assessment, and dynamometric and pedobarographic measurements. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:903–910. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1231-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hove LM, Nilsen PT. Posterior tibial tendon transfer for drop-foot. 20 cases followed for 1–5 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:608–610. doi: 10.3109/17453679808999265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath S, Schreuders TA, Stam HJ, Hovius SE, Selles RW. Early active motion versus immobilization after tendon transfer for foot drop deformity: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2477–2484. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1342-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibbo C, Baronofsky HJ, Jaffe L. Combined total ankle replacement and modified bridle tendon transfer for end-stage ankle joint arthrosis with paralytic dropfoot: report of an unusual case. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:453–457. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahinski JR, McHale KA, Temple HT, Jackson JP. Bridle transfer for paresis of the anterior and lateral compartment musculature. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:615–619. doi: 10.1177/107110079601701005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizel MS, Temple HT, Scranton PE, Jr, Gellman RE, Hecht PJ, Horton GA, et al. Role of the peroneal tendons in the production of the deformed foot with posterior tibial tendon deficiency. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:285–289. doi: 10.1177/107110079902000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tome J, Nawoczenski DA, Flemister A, Houck J. Comparison of foot kinematics between subjects with posterior tibialis tendon dysfunction and healthy controls. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:635–644. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness ME, Long J, Marks R, Harris G. Foot and ankle kinematics in patients with posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Gait Posture. 2008;27:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neville C, Flemister AS, Houck JR. Deep posterior compartment strength and foot kinematics in subjects with stage II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31:320–328. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2010.0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertullo CJ, Nunley JA. Acquired flatfoot deformity following posterior tibial tendon transfer for peroneal nerve injury : a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1214–1217. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200207000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson MC, Harrington ME, Thompson N, O’Connor JJ, Theologis TN. Kinematic analysis of a multi-segment foot model for research and clinical applications: a repeatability analysis. J Biomech. 2001;34:1299–1307. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller MJ, Sinacore DR, Hastings MK, Strube MJ, Johnson JE. Effect of Achilles tendon lengthening on neuropathic plantar ulcers. A randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:1436–1445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimera NJ, Castro M, Manal K. Function and Strength Following Gastrocnemius Recession for Isolated Gastrocnemius Contracture. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31:377–384. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2010.0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammarco GJ, Bagwe MR, Sammarco VJ, Magur EG. The Effects of Unilateral Gastrocsoleus Recession. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:508–511. doi: 10.1177/107110070602700705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JE, Harris GF. Pathomechanics of Posterior Tibial Tendon Insufficiency. Foot Ankle Clinics. 1997;2:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Jan MH, Chai HM, Lin YF, Lin JC, Tsai LY, Ou YC, et al. Effects of age and sex on the results of an ankle plantar-flexor manual muscle test. Phys Ther. 2005;85:1078–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunsford BR, Perry J. The standing heel-rise test for ankle plantar flexion: Criterion for normal. Phys Ther. 1995;75:694–698. doi: 10.1093/ptj/75.8.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.