Abstract

AbstractHippocampal gamma oscillations have been associated with cognitive functions including navigation and memory encoding/retrieval. Gamma oscillations in area CA1 are thought to depend on the oscillatory drive from CA3 (slow gamma) or the entorhinal cortex (fast gamma). Here we show that the local CA1 network can generate its own fast gamma that can be suppressed by slow gamma-paced inputs from CA3. Moderate acetylcholine receptor activation induces fast (45 ± 1 Hz) gamma in rat CA1 minislices and slow (33 ± 1 Hz) gamma in CA3 minislices in vitro. Using pharmacological tools, current-source density analysis and intracellular recordings from pyramidal cells and fast-spiking stratum pyramidale interneurons, we demonstrate that fast gamma in CA1 is of the pyramidal–interneuron network gamma (PING) type, with the firing of principal cells paced by recurrent perisomal IPSCs. The oscillation frequency was only weakly dependent on IPSC amplitude, and decreased to that of CA3 slow gamma by reducing IPSC decay rate or reducing interneuron activation through tonic inhibition of interneurons. Fast gamma in CA1 was replaced by slow CA3-driven gamma in unlesioned slices, which could be mimicked in CA1 minislices by sub-threshold 35 Hz Schaffer collateral stimulation that activated fast-spiking interneurons but hyperpolarised pyramidal cells, suggesting that slow gamma frequency CA3 outputs can suppress the CA1 fast gamma-generating network by feed-forward inhibition and replaces it with a slower gamma oscillation driven by feed-forward inhibition. The transition between the two gamma oscillation modes in CA1 might allow it to alternate between effective communication with the medial entorhinal cortex and CA3, which have different roles in encoding and recall of memory.

Introduction

Synchronisation of neuronal activity at frequencies in the gamma band (30–100 Hz) has been implicated in higher cognitive functions. Gamma synchronisation provides millisecond precision to the outputs of spatially distributed neurons, required for binding of information (Fries et al. 2007), synaptic integration and plasticity (Schaefer et al. 2006). Gamma oscillations (γ) in the hippocampus have been associated with navigation by theta phase precession of place cells (Jensen & Lisman, 2005; Lisman, 2005) and with hippocampus-based memory encoding/retrieval (Montgomery & Buzsaki, 2007; Colgin et al. 2009; Colgin & Moser, 2010; Carr et al. 2012; Carr & Frank, 2012). In vivo studies have shown that γ in cornu ammonis area 1 (CA1) has distinct high- and low-frequency components that differentially couple CA1 activity to high-frequency γ in the medial entorhinal cortex and to low-frequency γ in cornu ammonis area 3 (CA3) respectively (Bragin et al. 1995; Montgomery & Buzsaki, 2007; Colgin et al. 2009). This transition between two γ modes allows dynamic coupling and subsequent routing of information (Colgin & Moser, 2010; Carr & Frank, 2012), which is modulated by theta (Senior et al. 2008; Colgin et al. 2009) and dependent on behavioural demands (Montgomery & Buzsaki, 2007; Carr et al. 2012; Carr & Frank, 2012). It is not clear how the two γ modes can emerge from the same CA1 network.

In vivo studies suggest that CA1 γ is driven by γ-generating networks in CA3 and the medial entorhinal cortex (Bragin et al. 1995; Csicsvari et al. 2003). Lesion studies in vitro have identified CA3 as the γ generator driving γ in CA1 (Fisahn et al. 1998; Fellous & Sejnowski, 2000; Bibbig et al. 2007), through feed-forward inhibition (Bibbig et al. 2007; Zemankovics et al. 2013). However, the feed-forward inhibition evoked by high-frequency medial entorhinal cortex inputs modulates CA1 excitability at a different timescale (Remondes & Schuman, 2002) and is unlikely to drive fast γ in CA1 directly. It was therefore proposed that “in the absence of particularly strong activation of CA3, the default gamma mode in CA1 during active behaviours may be fast gamma oscillations” (Colgin & Moser, 2010)

Indeed, CA1 can generate its own γ under specific conditions: in the absence of fast glutamatergic transmission, mutually connected CA1 interneurons, activated by metabotropic glutamate receptors, synchronise their activity at gamma frequencies (Whittington et al. 1995). Gamma oscillations can also be induced in CA1 by very strong excitatory treatments, like tetanic stimulation (Whittington et al. 1995; Vreugdenhil et al. 2005) or focal application of micromolar kainate (Kipiani, 2009) in intact slices, or in isolated CA1 slices by very high concentrations of kainate (Traub et al. 2003; Middleton et al. 2008; Kipiani, 2009) or metabotropic glutamate receptor agonists (Bibbig et al. 2007). However, the conditions required to evoke γ in the CA1 network question whether the CA1 local network can generate γ under more physiological conditions and why this is suppressed by CA3 γ.

Here we show that moderate acetylcholine receptor activation induces intrinsic fast γ in area CA1, which can be suppressed and replaced by feed-forward inhibition-driven slow γ, in response to slow γ frequency inputs from CA3.

Methods

Ethical approval

All procedures conformed to the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and were approved by the local Biomedical Ethics Review committee.

Tissue preparation

A total of 74 adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (200–300 g, Charles-River, Margate, UK) were anaesthetised by intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine (75 mg kg−1)–medetomidine (1 mg kg−1) mixture. On absence of pedal reflex, the abdomen and thorax were opened, the portal vein was cut and the left ventricle was perfused (at 13 ml min−1 through a 21 gauge needle) with 50 ml chilled sucrose-based solution. The sucrose-based solution consisted of 205 mm sucrose, 2.5 mm KCl, 26 mm NaHCO3, 1.2 mm NaH2PO4, 0.1 mm CaCl2, 5 mm MgCl2 and 10 mm d-glucose, and was saturated with carbogen (95% O2–5% CO2), keeping the pH at 7.4. The brain was removed from the skull and, after removing the cerebellum and brainstem, glued upside-down on a chilled cutting block (see Supplemental Fig. S1Ai). Horizontal slices (400 μm thick) were cut from the ventral side (corresponding to 4.5–6.5 mm ventral to Bregma) in chilled sucrose-based solution, using an Integraslicer (Campden Instruments, Loughborough, UK) with a ceramic blade. Slices from the left hemisphere were trimmed in chilled sucrose-based solution to contain the hippocampus with overlaying cortex (see Supplemental Fig. S2Ai) and immediately placed in the Haas-type interface recording chamber, perfused at 7 ml min−1 with warm (32 °C) artificial CSF (aCSF) and covered with warm moist carbogen (0.3 l min−1). The aCSF consisted of 125 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, 26 mm NaHCO3, 1.25 mm NaH2PO4, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2 and 10 mm d-glucose, and was saturated with carbogen (pH at 7.4). Gamma oscillations (γ) were induced by addition of the acetylcholine receptor agonist carbamylcholine chloride (carbachol, 10 μm) after 60 min of rest. After initial recordings in intact slices, a scalpel cut was made through CA2 and dentate gyrus to produce an isolated CA1 slice and a CA3 minislice (Supplemental Fig. S2Aii). Electrodes were carefully repositioned and recordings were restarted after 10 min recovery.

Slices from the right hemisphere were trimmed with scalpel cuts in chilled sucrose-based solution to obtain CA1 minislices (see Fig. 1A) and maintained in aCSF at room temperature in an interface-type storage chamber for later use.

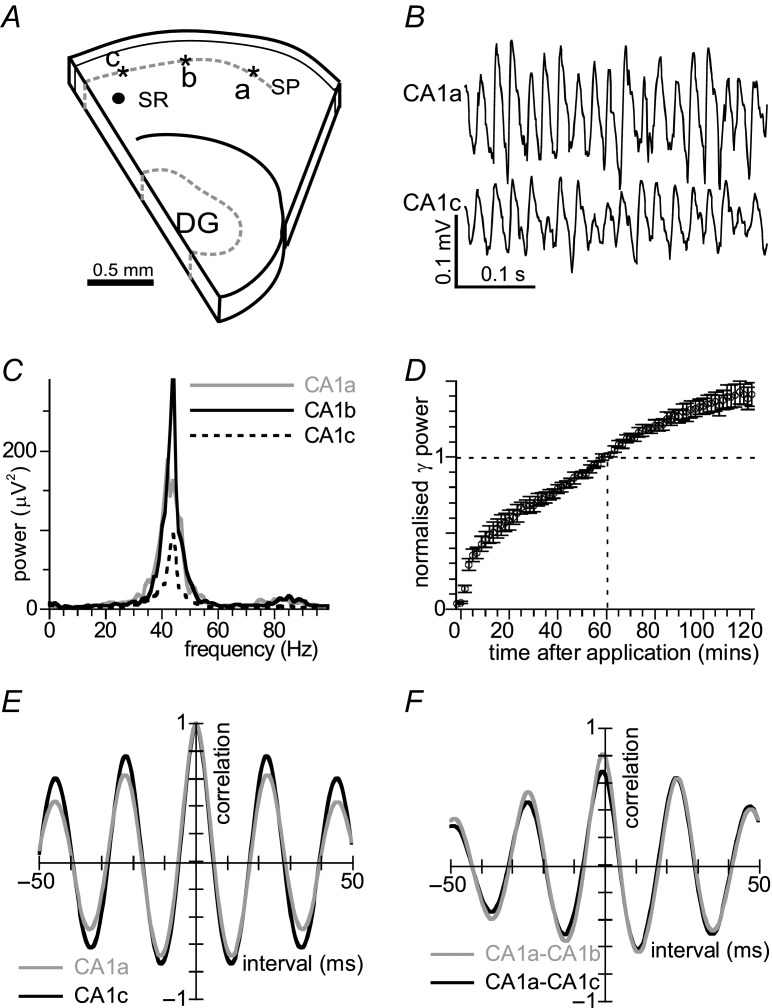

Figure 1.

A, schematic drawing of a CA1 minislice, obtained by a placing a cut through CA2 and dentate gyrus and a second cut through the subiculum, lesioning inputs from CA3 and entorhinal cortex. Extracellular recording electrodes (asterisks) were placed in stratum pyramidale (SP) of CA1a, CA1b and CA1c and a stimulation electrode in stratum radiatum (SR, black circle) of CA1c. B, example of oscillatory activity induced by carbachol (10 μm) recorded in CA1a (top) and CA1c (bottom). Oscillations are regular and phase-locked. C, power spectra from recordings in CA1a, CA1b and CA1c of the slice in B, shows regional differences in power, but not in dominant frequency. D, development of γ power (average power in the 20–70 Hz band, normalised to γ power at 60 min) over 2 h after application of carbachol (10 μm). Data are means ± SEM for n = 12. E, auto-correlogram of the recording from CA1b of the slice in B. F, cross-correlogram of the recordings from the slice in B with CA1a as reference. The cross-correlation maximum shows strong phase synchrony throughout CA1.

Drugs

Drugs were added to the aCSF from the following stock solutions: carbachol, 10 mm in H2O; the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor selective antagonist pirenzepine dihydrochloride, 10 mm in H2O; the NMDA receptor antagonist d-2-amino-phosphonovaleric acid (APV), 25 mm in 0.1 m NaOH; the broad-spectrum metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist (S)-a- methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG), 100 mm in 0.1 m NaOH; the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline methiodide, 2 mm in H2O; the sodium–sodium carbonate mixture of the barbiturate (±)-thiopental, 20 mm in H2O, the δ subunit-containing GABAA receptor agonist 4,5,6,7,-tetrahydroixoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridine-3-ol hydrochloride (THIP), 1 mm in H2O; the AMPA receptor antagonist (±)-4-(4-aminophenyl)-1,2-dihydro-1-methyl-2- propylcarbamoyl-6,7-methylenedioxyphthalazine (SYM 2206), 50 mm in dymethyl sulfoxide. APV, MCPG, SYM 2206 and THIP were purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK). All other drugs and aCSF salts were purchased from Sigma (Poole, UK).

Electrophysiological recordings

Field potentials were recorded using aCSF-filled glass pipette recording electrodes (4–5 MΩ), amplified with Neurolog NL104 AC-coupled amplifiers (Digitimer, Welwyn Garden City, UK), band-pass filtered at 2–500 Hz with Neurolog NL125 filters (Digitimer). After mains line noise was removed with Humbug noise eliminators (Digitimer), the signal was digitised and sampled at 2 kHz using a CED-1401 Plus (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK) and Spike-2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design).

For the laminar profile of activity, recordings were made with a roving electrode recording from different places (50 μm apart) in a line perpendicular to stratum pyramidale, with a second electrode static in stratum pyramidale.

Schaffer collaterals were stimulated by 0.1 ms square pulses, using a bipolar twisted 50 μm diameter nickel–chromium wire (Advent Research Materials Ltd, Halesworth, UK) and a DS2A isolated stimulator (Digitimer).

Intracellular current-clamp recordings were made from neurons in stratum pyramidale in close proximity (<0.2 mm) to the extracellular electrode, using sharp (50–100 MΩ) pipettes filled with 3 m KCH3SO4. The membrane potential (Vm) was amplified using an Axoclamp-2A amplifier (Axon Instruments, Burlingham, CA, USA) and a Neurolog NL106 DC amplifier, low-pass filtered at 2 kHz with a Neurolog NL125 filter, and then sampled at 10 kHz. Impaled cells were first inspected and accepted for recording if the input resistance was greater than 30 MΩ, the Vm in the absence of holding current was stable and more polarized than −55 mV, and action potentials overshot. Neurons were identified as pyramidal cell or interneuron, based on the responses to 0.2 s current injections (ranging from −1 to +1.5 nA). Neurons were considered pyramidal cells if the membrane time constant was >15 ms, the first action potential halfwidth was >0.8 ms, the fast afterhyperpolarisation amplitude was <5 mV, and if they displayed clear accommodation of firing at strong depolarizing current injections. Cells were considered to be interneurons if the membrane time constant was <10 ms, the action potential halfwidth was <0.6 ms, the fast afterhyperpolarisation amplitude was >10 mV and they displayed no accommodation (details in Supplemental Fig. S3).

In a different set of stratum pyramidale neurons, membrane currents (Im) were recorded in discontinuous single electrode voltage-clamp mode using an Axoclamp-2A amplifier with a switch rate of >5 kHz and a gain of >10. For these recordings the pipettes (60–110 MΩ) were filled with 3 m CsCH3SO4 and 10 μm QX314, to increase membrane resistance and suppress firing, thus aiding voltage control, which was >90%. Im was amplified using a Neurolog NL106 DC amplifier, low-pass filtered at 2 kHz with a Neurolog NL125 filter and then sampled at 10 kHz. Impaled cells were first recorded in current clamp to be assessed as above, before firing was suppressed by diffusion of the pipette solution, and were accepted for voltage-clamp recording if Im at −60 mV was less than −0.5 nA.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Spike-2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design). The oscillation power was calculated by fast Fourier transforms (1 Hz bin size, Hamming window) from recording epochs >60 s. The dominant frequency was determined as the local maximum in the 7-point sliding average-smoothed power spectrum. The gamma frequency band was set at 20–70 Hz for recordings at 32°C, taking into account the temperature dependence of γ observed in the hippocampus (Dickinson et al. 2003). The criterion used for distinguishing a power peak in the gamma frequency band was that the smoothed power spectrum maximum in the gamma band was >10% higher than the average power in the 10–20 Hz band. Waveform auto-correlogram and cross-correlograms were calculated over 60-s band-pass (10–200 Hz) finite impulse response (FIR) filtered epochs. To obtain a measure of the fluctuations in γ power, the root mean square amplitude of the band-pass filtered recording was low-pass (FIR at 10 Hz) filtered. Cross-correlograms between γ power fluctuations were calculated over 600-s epochs.

Waveform averages

To obtain averages of γ cycles at different amplitude ranges, first an ‘extreme’ amplitude threshold was set such that on average the trough-to-peak amplitude of one γ cycle per second from the band-pass filtered (FIR at 20–70 Hz) recording from stratum pyramidale exceeded this threshold. This ‘extreme’ γ cycle amplitude was then used to normalise the amplitude of all γ cycles. Gamma oscillation cycles were then sorted into six amplitude ranges (10–20%, 20–40%, 40–60%, 60–80%, 80–100% and >100% of the ‘extreme’ γ cycle amplitude for that recording). For each amplitude range, waveform averages of γ cycles (>300 γ cycles, time-zeroed at the sorted marks) were then calculated from the unfiltered recordings (Oke et al. 2010). Waveform averages were also obtained for responses evoked by electrical stimulation, time-zeroed at the stimulus.

To calculate the current-source density (CSD) from the laminar profile recordings, waveform averages were calculated for each recording position from >300 medium-size (0.4–0.6 of the ‘extreme’ γ cycle amplitude in recordings from stratum pyramidale) γ cycles as above. A one-dimensional CSD profile was then calculated from the waveform averages. Because the real value of the conductivity tensor is difficult to determine and the sampling distance was fixed, we used the simplified equation: CSD = –(Ex–h – 2Ex + Ex+h) where Ex is the field potential at location x and h is the sampling distance (Vreugdenhil et al. 2005). Although this dimensionless measure is only proportional to the true current source density, it allows comparison of relative differences in CSD.

Spike timing intervals were calculated between the times of action potential peaks and the times of larger (>0.4 of the ‘extreme’ γ cycle amplitude) troughs in the band-pass filtered (FIR at 20–70 Hz) recording from stratum pyramidale. To determine whether the action potential timing was phase-locked to the field potential oscillation, the intervals were expressed as degrees of the γ cycle and their distribution was tested for circular non-uniformity using Rayleigh's uniformity test. If P < 0.05 it was assumed that the firing probability was modulated by the gamma oscillation.

To compensate intracellular Vm recordings for large extracellular field oscillations, the trans-membrane potential was obtained by subtracting the field potential recorded in stratum pyramidale from the Vm recording.

To determine the reversal potential of γ-associated currents, waveform averages (time-zeroed to the trough of medium-size γ cycles in stratum pyramidale) were calculated from Im recordings at different holding potentials. Im was determined from the waveform averages for each holding potential, at the time of the peak of the waveform average for −10 mV. Im as a function of Vm showed substantial rectification and was therefore fitted with a growing exponential function, from which the reversal potential (Vm where Im = 0) was calculated.

Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical comparisons between of group means were made using paired and unpaired Student's t tests, because all data samples did not differ from a normal distribution (Shapiro Wilks test >0.05). Pearson's correlation coefficient was determined for bivariate correlations. Effects were considered significant if P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Rayleigh's uniformity test was used to determine the phase locking of action potentials to oscillations using Oriana 4 (Kovach Computing Services, Anglesey, UK).

Results

Fast gamma oscillations in CA1 minislices

We tested whether a cholinergic drive can generate intrinsic gamma oscillations in CA1 minislices, created by cutting CA1 free from both CA3 and subiculum (Fig. 1A). Electrodes were placed in stratum pyramidale of sub-areas CA1a, CA1b and CA1c. Oscillatory activity was induced by addition of carbachol (10 μm) to the aCSF (example in Fig. 1B). The power spectra from these recordings show a single distinguishable power peak (criterion in Methods) in the gamma frequency band (Fig. 1C) in 63 out of 78 minislices tested. Figure 1D gives the development of the γ power (average power in the 20–70 Hz band) over 2 h in 12 minislices with a distinguishable power peak. Gamma oscillations (γ) in CA1 developed rapidly in the first half hour, compared to γ recorded in CA3 under similar conditions (see Supplemental Fig. S4B). Gamma oscillation power continued to increase gradually for up to 4 h and Fig. 1D suggests a second growth phase developing after ∼40 min. The gamma oscillation was normally largest in area CA1b, where γ power was 52 ± 3 μV2 after 1 h in carbachol in 63 CA1 minislices. The dominant frequency in these minislices was 45 ± 1 Hz, substantially higher than the dominant frequency (33 ± 1 Hz) of γ evoked in CA3b of 53 intact slices recorded under identical conditions and with a similar γ power (48 ± 5 μV2). The oscillation was very regular, reflected by peaks of 0.53 ± 0.04 at 23 ± 1 ms in the auto-correlogram of 12 slices (example in Fig. 1E). The oscillation in these slices was spatially very coherent, reflected by the peak in the cross-correlogram between CA1a and CA1b (example in Fig. 1F), with a maximum of 0.73 ± 0.03 and no phase difference (0.0 ± 0.1 ms). CA1 minislices cut from coronally sectioned slices had much smaller and spatially less coherent CA1 γ (Supplemental Fig. S1).

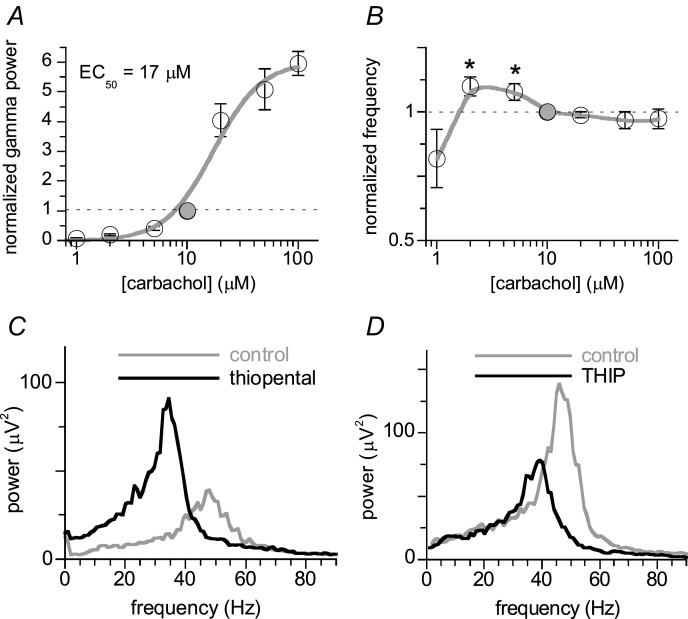

CA1 gamma oscillation pharmacology

The carbachol concentration dependence of the CA1 γ was tested in 18 CA1 minislices with the recording electrode in CA1b stratum pyramidale. In order to control for the large variability in γ power we used three 30-min incremental carbachol concentration steps, including a concentration of 10 μm. For each slice the γ power after 30 min in each concentration was normalised to the γ power in 10 μm. Normalised γ power as a function of carbachol concentration (Fig. 2A) was fitted with a sigmoid function of the form: effect = maximum effect/(1 + ([carbachol]/EC50)−2). The half-maximum effect concentration (EC50) was 17.0 ± 1.9 μm with a maximum effect of 6.0 ± 1.9 times the γ power at 10 μm (49 ± 7 μV2). For these slices the dominant frequency in the gamma range was for each concentration step normalised to the frequency in 10 μm (Fig. 2B). Small amplitude γ evoked by low carbachol concentrations was slightly faster than that at 10 μm (44 ± 1 Hz), but increasing γ power at higher concentrations did not affect the dominant frequency (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Recordings were made in CA1b stratum pyramidale of CA1 minislices. A, concentration–effect relationship constructed from recordings in 18 slices exposed to three 30-min incremental carbachol concentration steps, including 10 μm. The γ power (average power in the 20–70 Hz band) at the end of each concentration step, normalised to the γ power at 10 μm (filled symbol), as a function of carbachol concentration, was fitted with a sigmoid function (see text) with an EC50 of 17.0 ± 1.9 μm. Data are means ± SEM for n = 6 except for 10 μm. B, concentration–effect relationship of the dominant frequency of the oscillations in A, normalised to the dominant frequency at 10 μm carbachol. Details as in A. Line is smooth fit; paired Student's t test; *P < 0.05 for comparisons with the 10 μm values. C, example of a power spectrum before (grey line) and after 20 min in the barbiturate thiopental (20 μm, black line). D, example of the effect of the δ subunit-containing GABAA receptor agonist THIP (1 μm). Details as in C.

The effect of pharmacological modulation of fast γ in CA1 was assessed in CA1 minislices after 60 min in 10 μm carbachol. Because γ power gradually increased with time, the effect of drugs 20 min after application (change from baseline values averaged over 3 min before drug application) was compared (using between-group tests) with the changes observed in nine time-matched control slices (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pharmacology of fast γ in CA1

| Drug | Concentration (μm) | n | Power change from baseline (%) | P (t test with control) | Frequency change from baseline (Hz) | P (t test with control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | — | 9 | 123 ± 5 | — | 0.8 ± 0.3 | — |

| Pirenzepine | 10 | 4 | 3 ± 1 | 0.004 | n.a. | — |

| APV | 25 | 6 | 124 ± 14 | n.s. | 0.4 ± 0.9 | n.s. |

| MCPG | 500 | 4 | 137 ± 13 | n.s. | 0.7 ± 1.4 | n.s. |

| SYM 2206 | 10 | 6 | 8 ± 2 | 0.018 | n.a. | — |

| Bicuculline | 2 | 5 | 26 ± 5 | <0.001 | 2.3 ± 1.2 | n.s. |

| Thiopental | 20 | 14 | 152 ± 15 | 0.019 | –8.4 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| THIP | 1 | 6 | 41 ± 5 | <0.001 | –8.1 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

The effect of drugs on fast γ in CA1 was assessed in CA1 minislices after 60 min in 10 μm carbachol. The changes in gamma power and dominant frequency 20 min after bath application of drugs are compared with the time-matched changes in controls, using unpaired Student's t tests. Data are given as means ± SEM, with n indicating the number of slices tested.

Whereas CA1 γ power was not affected by the NMDA receptor antagonist APV or the broad-spectrum metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist MCPG (Table 1), the muscarinic acetylcholine M1 receptor selective antagonist pirenzepine blocked γ, indicating that the carbachol-induced CA1 γ is largely driven by M1 receptor activation, with little contribution of metabotropic glutamate receptors and NMDA receptors.

The selective AMPA receptor antagonist SYM 2206 blocked CA1 γ power (Table 1) indicating that fast glutamatergic inputs are essential.

A low (non-convulsive) concentration of the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline methiodide suppressed CA1 γ power (Table 1), supporting the hypothesis that CA1 γ is inhibition based. The barbiturate thiopental, which is known to prolong IPSCs in CA1 pyramidal cells (Traub et al. 1996; Pittson et al. 2004), reduced the dominant frequency of CA1 γ and increased γ power (Table 1; example in Fig. 2C), confirming the role of IPSC kinetics in pacing the oscillation.

These observations show that the pharmacology of fast γ in CA1 is very similar to that of the slower inhibition-based γ generated in CA3 (Traub et al. 1996, 2000; Fisahn et al. 1998; Palhalmi et al. 2004; Mann et al. 2005).

The frequency of carbachol-induced γ in CA3 was shown to be dependent on the tonic excitatory drive to interneurons and reduced by extra-synaptic tonic GABAA-ergic currents, mediated by δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors selectively expressed on interneurons (Mann & Mody, 2010). Here, the specific agonist for δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors THIP reduced the dominant frequency by 8.1 ± 1.0 Hz (Table 1; example in Fig. 2D).

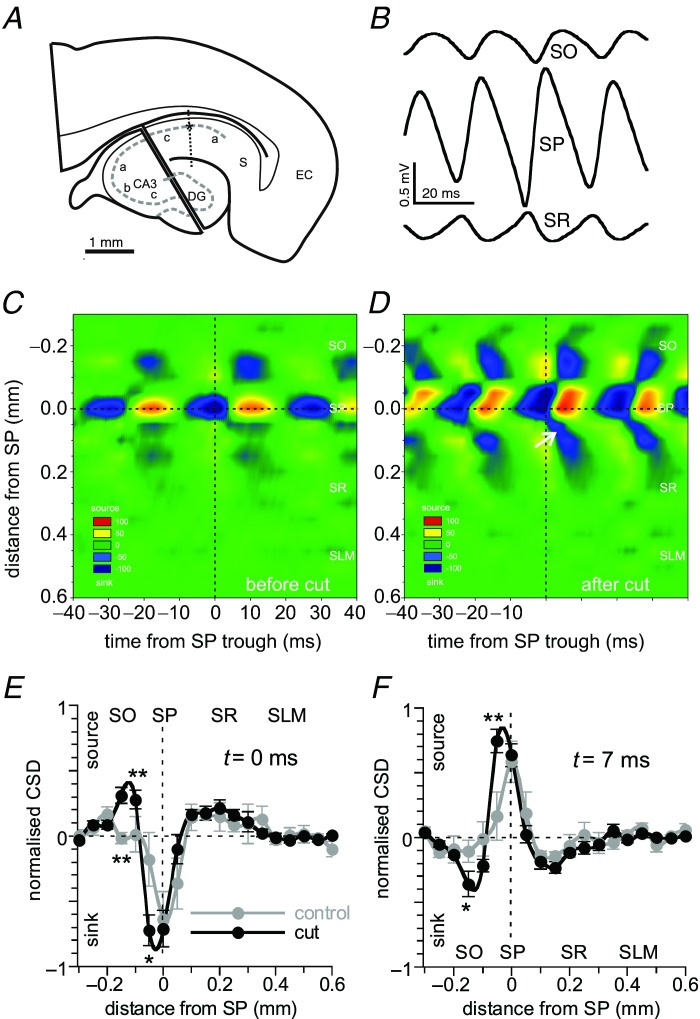

Laminar distribution of CA1 gamma oscillations

Gamma oscillations in CA3 show the strongest sink–source sequence at the stratum pyramidale–stratum lucidum (Pietersen et al. 2009). In isolated CA1 slices (cut like in Fig. 3A) the laminar distribution of CA1 γ activity was determined from recordings made in CA1b from positions 50 μm apart, perpendicular to stratum pyramidale (see Fig. 3A). Maximal γ power was recorded at the stratum oriens–stratum pyramidale border (not shown). Waveform averages were made from recordings taken at different positions along the cell axis, time-zeroed at the trough of medium-sized γ cycles recorded in stratum pyramidale (examples in Fig. 3B). A one-dimensional current-source density (CSD) analysis was made from the waveform averages to construct CSD time–space plots that showed a sink–source sequence in stratum pyramidale (example in Fig. 3D). The CSD (normalised to the maximum sink) space profile at the time of the trough in CA1 stratum pyramidale showed a sink situated in the stratum pyramidale–stratum oriens border (Fig. 3E, black symbols), which was replaced by a source at t = 7 ms at the same location (Fig. 3F, black symbols). This suggests that the phasic currents driving γ in CA1 are located in stratum pyramidale–oriens border.

Figure 3.

A, schematic drawing of an isolated CA1 slice, obtained by a placing a cut through CA2 and dentate gyrus. Recordings were made from positions 50 μm apart (dots) perpendicular to stratum pyramidale, with a static electrode in stratum pyramidale (asterisk). B, waveform averages (time-zeroed at the trough of medium-sized γ cycles in SP; dashed line) were made of each position. Examples are shown for stratum oriens (SO), SP and stratum radiatum (SR). C, a one-dimensional CSD analysis was made from the waveform averages. Example of the CSD as function of time and space of CA3-driven CA1 γ in the intact slice. SLM, stratum lacunosum/moleculare. CA3-driven γ in CA1 is a simple sequence of sources following sinks in SP. D, same slice as in C after isolation. The loss of inputs from CA3 increased the sinks and sources in SP, which now extend into the SP–SO border. Note that the sink at 0 ms moves into SR (white arrow), indicative of action potentials invading the apical dendrite. E, CSD space profile at the time of the sink in stratum pyramidale (t = 0). Data are means ± SEM of five slices, normalised per slice to the maximum sink and given as a function of distance from SP, before (grey symbols) and after a cut through CA2 (black symbols). Care was taken that similar-sized γ cycles were used in both conditions. Lines are smooth fits; paired Student's t test; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. After the cut the main sink extends from SP towards SO. F. Same as E at t = 7 ms after the trough in stratum pyramidale, where the current source was maximal in most slices. After the cut the main source extends towards stratum oriens.

In the CSD time–space plots the sink moved from stratum pyramidale into stratum radiatum (arrow in Fig. 3D), indicative for action potentials invading the apical dendrite up to 200 μm (Kloosterman et al. 2001).

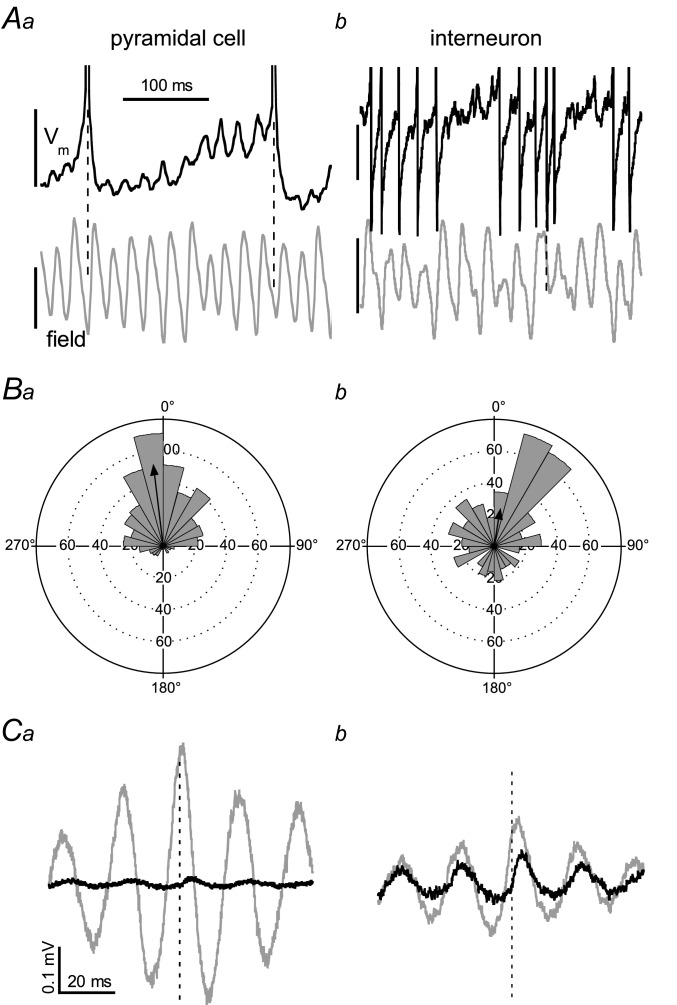

Intracellular recordings

In order to determine whether the γ-related sinks or sources were active or passive we recorded the membrane potential (Vm) of neurons located close to the extracellular recording electrode in the CA1 stratum pyramidale of isolated CA1 slices. Neurons were identified as pyramidal cell or interneuron by their response to hyperpolarising and depolarising current injections (see Methods and Supplemental Fig. S3). In the absence of holding current, but in the presence of carbachol, nine cells identified as pyramidal cells (example in Fig. 4Aa) and four cells identified as fast-spiking interneurons (example in Fig. 4Ab) fired spontaneously. Under this condition the Vm (excluding firing) was −55.7 ± 2.1 mV for fourteen pyramidal cells and −57.2 ± 1.1 mV for the four interneurons. To determine the relationship between firing and the extracellular γ phase, the firing rate was set to ∼2 Hz by adjusting DC current injection. The distribution of intervals between the action potential peak time and the γ cycle trough was non-uniform (Rayleigh's uniformity P < 0.05) in 11 of the pyramidal cells, demonstrating phase locking of firing to the γ cycle (example in Fig. 4Ba). The mean vector length r was 0.365 ± 0.060 and the mean vector angle was −7.7 ± 7.4 deg. This corresponds in real time to a maximum firing probability −0.5 ± 0.4 ms ahead of the γ cycle trough. The firing of the three remaining pyramidal cells was unrelated to the γ phase (Rayleigh's uniformity test P < 0.05, r = 0.046 ± 0.017), but they did not differ in any other respect from the phase-locked cells. The fast-spiking interneurons were all phase-locked to the γ cycle (r = 0.456 ± 0.088, at 23.4 ± 6.0 deg). Their firing probability maximum was 1.5 ± 0.4 ms after the γ cycle trough (example in Fig. 4Bb), significantly later than the phase-locked pyramidal cells (Student's t13 = −2.55, P = 0.024).

Figure 4.

Neurons were recorded in CA1b stratum pyramidale of isolated CA1 slices using sharp electrodes, with an extracellular electrode placed nearby in stratum pyramidale. A, simultaneous recording of the trans-membrane potential (Vm, black trace, 5 mV scale bar) and the field potential (grey trace, 0.2 mV scale bar) in a typical pyramidal cell (a) and a typical fast-spiking interneuron (b), both held near firing threshold. Hyperpolarising Vm events coincide with positive-going field potentials and action potentials coincide mostly with γ cycle troughs. B, rose plots of the intervals between γ cycle troughs (reference = 0°) and action potential peaks for the pyramidal cell (a) and the interneuron (b) shown in A. The inter-event interval distribution was non-uniform for the pyramidal cell (mean vector length r = 0.63, with a mean angle = −7 deg and the interneuron (r = 0.29, angle = 9 deg), showing firing probability was maximal just before and just after the γ cycle trough respectively. C, the trans-membrane potential waveform average (time-zeroed at the trough of medium-sized γ cycles, dashed line) for the pyramidal cell (a) and the interneuron (b) shown in A, when held near firing threshold (grey line) and when hyperpolarised to −70 mV (black line). Close to the GABAA receptor gated current reversal potential γ associated Vm fluctuations were minimal in the pyramidal cell, indicating that the waveform mainly reflects γ phase-locked IPSPs, but the interneuron showed clear EPSPs as well.

The Vm of pyramidal cells showed rhythmic synaptic potentials, in phase with the γ in stratum pyramidale (example in Fig. 4Aa). Waveform averages were made from the base line-corrected trans-membrane potential, time-zeroed at the trough of medium-sized γ cycles in stratum pyramidale. When pyramidal cells were held just below firing threshold, the peak-to-trough amplitude was 0.53 ± 0.05 mV, with a peak at 1.1 ± 0.2 ms and a trough at 10.3 ± 0.5 ms (n = 14; example in Fig. 4Ca, grey trace). For the four fast-spiking interneurons the amplitude was 0.33 ± 0.12 mV, with a peak at 2.0 ± 0.6 ms and a trough at 11.0 ± 0.9 (example in Fig. 4Cb, grey trace). When cells were hyperpolarised to −70 mV, close to the GABAA receptor gated current reversal potential (see below), most pyramidal cells showed small or no discernible trans-membrane potential oscillations. Five other cells had discernible positive-going synaptic potentials (0.07 ± 0.03 mV, peaking at 5.2 ± 0.5 ms, example in Fig. 4Ca, black trace). When held at −70 mV, all fast-spiking interneurons had discernible positive-going potentials (0.17 ± 0.04 mV, peaking at 4.3 ± 0.3 ms, example in Fig. 4Cb, black trace).

These observations suggest that during fast γ CA1 pyramidal cells can fire upon cessation of the IPSP, with little or no contribution of EPSPs, whereas EPSPs play a significant role in interneuron firing.

To investigate the nature of the synaptic potentials ten CA1 pyramidal cells were recorded in voltage clamp and held at voltages ranging from −10 to −100 mV with 10 mV increments. At −10 mV, close to the assumed reversal potential of excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs), Im fluctuated rhythmically in phase with the field potential in stratum pyramidale (Fig. 5A). For 10 cells the cross-correlation between Im at –10 mV and the field potential (reference) had a maximum of 0.72 ± 0.04 at 0.3 ± 0.5 ms. Waveform averages were constructed from base line-corrected Im (time-zeroed to the trough of γ cycles in stratum pyramidale), for six different γ cycle size ranges (see Methods; example in Fig. 5B). The IPSC amplitude at −10 mV correlated strongly with that of the field potential in stratum pyramidale (Pearson's r = 0.98 ± 0.01, P < 0.01, Fig. 5C). These observations suggest that, like in CA3 γ (Atallah & Scanziani, 2009), the extracellular field potential oscillation mainly reflects outward inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs). However, the instantaneous frequency (inverse of the interval to the next γ cycle) was only weakly related to IPSC amplitude (Fig. 5D, which differs from the strong relationship reported for CA3 γ (Atallah & Scanziani, 2009) and observed in CA3b stratum pyramidale of CA3 minislices (Supplemental Fig. S5).

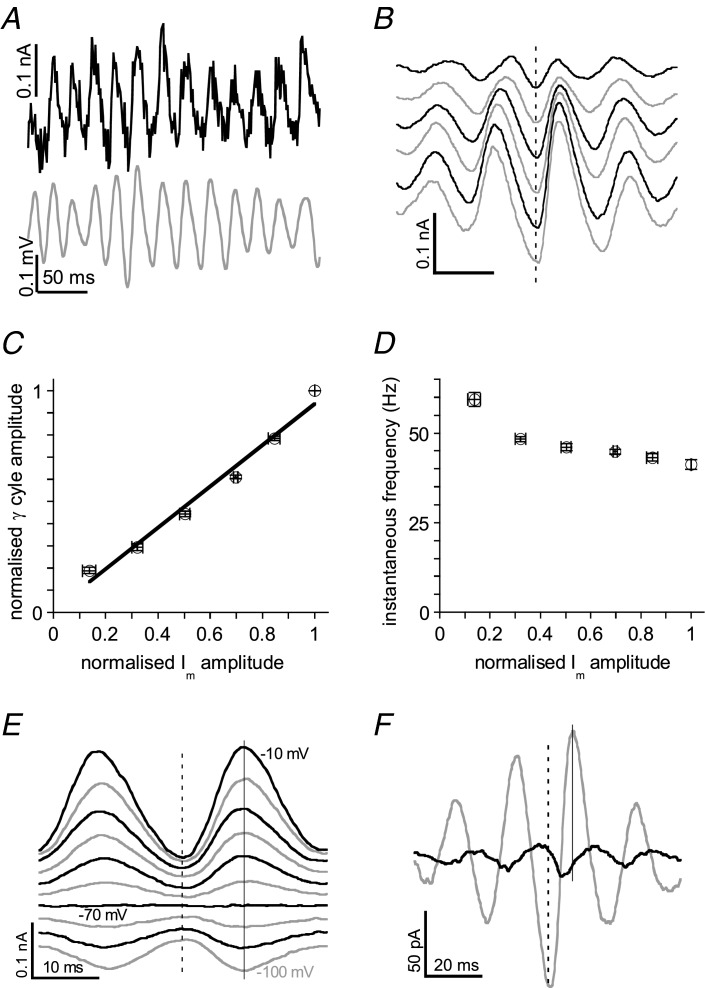

Figure 5.

CA1b pyramidal cells were recorded in voltage clamp. A, example of a simultaneous recording of the field potential (grey trace) and membrane current (Im) in a pyramidal cell clamped at −10 mV (black trace). IPSCs coincide with positive-going field potentials. B, waveform averages of Im, time-zeroed at the trough of medium-sized γ cycles (dashed line) were made for six different γ cycle amplitude ranges (see Methods). Traces are transposed for clarity. C, the relation between Im amplitude and γ cycle amplitude (both normalised to their maximum) was fitted with a linear function. Data are means ± SEM of ten cells in nine slices. D, the relation between normalised Im amplitude and instantaneous frequency (inverse of interval to next γ cycle) shows only a weak relationship. Data as in C. E, waveform averages of Im at different holding potentials (10 mV increments) show reversal near −70 mV without a change in waveform kinetics (demonstrated by continuous grey line through amplitude maxima). Traces are transposed for clarity. F, waveform averages of Im for the cell in B held at 10 mV (grey line, representing mostly IPSCs) or at −70 mV (black line, representing mostly EPSCs), show that the EPSC trough precedes the IPSC peak.

For ten cells the IPSC amplitude (Im waveform average trough-to-peak) of medium-sized γ cycles in stratum pyramidale was 153 ± 36 pA and the IPSC peak time was 8.2 ± 0.2 ms after the γ cycle trough (n = 10). Im waveform averages of medium-sized γ cycles were constructed for each holding potential. Figure 5E gives an example of Im recorded at different holding potentials in a cell where the current waveform kinetics was independent of Vm. The reversal potential (see Methods) was −71.2 ± 1.2 mV in four cells of this type, not different from the reversal potential for mono-synaptic stimulus-evoked IPSCs in CA1 pyramidal cells in control solution (−70 mV; A.N.J.P. unpublished observations), suggesting little or no contribution of EPSCs in these cells. In the remaining cells the current waveform at −70 mV showed small rhythmic currents with kinetics different from those at −10 mV (example in Fig. 5F), suggesting that these cells had mixed synaptic currents. The current waveform average at −70 mV mainly reflects inward EPSCs (example in Fig. 5F, black line) and was for all 10 cells −8.6 ± 2.1 pA (peak-to-trough), with the trough at 4.4 ± 0.4 ms, 4.1 ± 0.5 ms ahead of the IPSC peak. The EPSC amplitude recorded at the soma was only 5 ± 1% of the IPSC amplitude, suggesting that mutual excitation of pyramidal cells plays a minor role in action potential generation during CA1 γ.

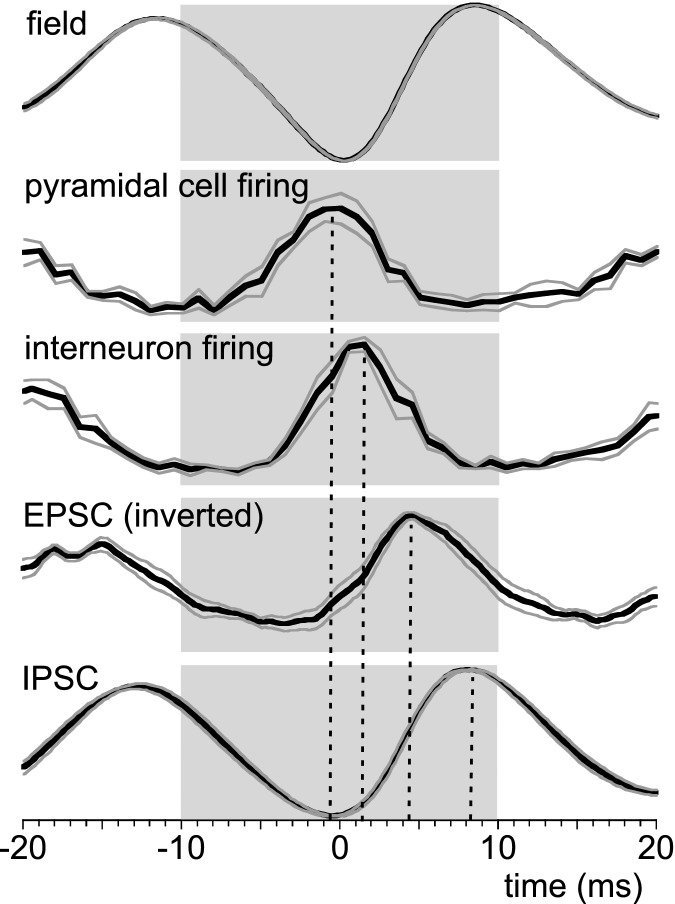

The sequence of events that can be deduced from these experiments (average time courses are given in Fig. 6) is that during a γ cycle some pyramidal cells fire just before the γ cycle trough in stratum pyramidale, followed in ∼2 ms by fast-spiking interneurons. Consequently pyramidal cells receive EPSCs curtailed by IPSCs.

Figure 6.

Waveform averages (details as in Figs 4 and 5) of field potential in stratum pyramidale (n = 20), pyramidal cell firing distribution (n = 11, only cells with distribution different from normal), interneuron firing distribution (n = 4), EPSCs (inverted to show its peak, n = 10) and pyramidal cell IPSCs (n = 10). Data are normalised to the maximum and minimum values (indicated by shaded areas). The black line is the average, grey lines give SEM The dashed lines indicate average times of peaks for the distribution/waveform average per cell.

Gamma oscillations in CA1 of intact slices

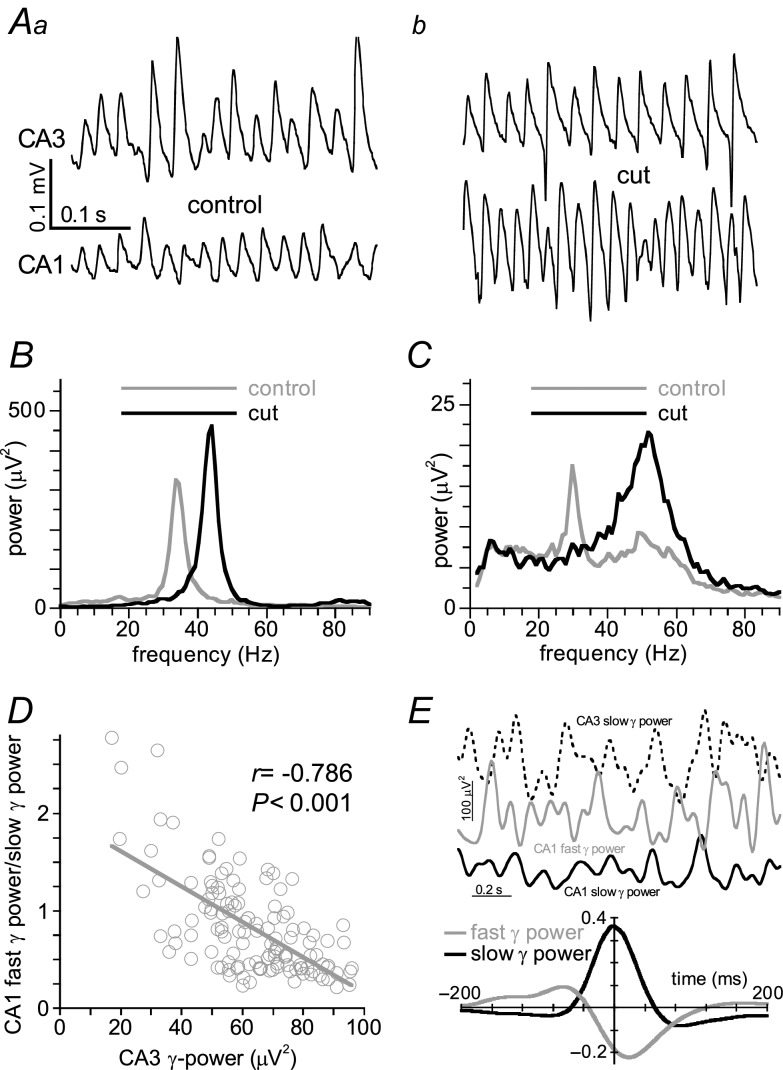

In intact hippocampal slices carbachol (10 μm) induced γ in both area CA3 and CA1. In 34 out of 53 intact slices the γ in CA1a was phase-locked to the slow γ in CA3b (example in Fig. 7Aa). In these slices the power spectrum in CA1a had a single peak in the gamma frequency band with a dominant frequency of 33 ± 1 Hz (example in Fig. 7B, grey line). The maximum cross-correlation was 0.41 ± 0.03 with CA3 γ leading CA1 γ by 1.2 ± 0.3 ms. The CSD space profile of the CA3-driven oscillation in CA1b (in the same slices and location as before isolating CA1) showed that both the sink and the source are situated more towards stratum radiatum (Fig. 3, black symbols). None of the CSD time–space plots showed an indication of action potentials invading the apical dendrite (example in Fig. 3C).

Figure 7.

Simultaneous recordings were made of carbachol-induced γ in CA3b and CA1a in intact hippocampal slices, before and after CA1 was isolated by a cut through CA2 (see Methods and Supplemental Fig. S2A). A, example of oscillations recorded in CA3 (top traces) and CA1 (bottom traces) from a slice where the oscillation in CA1 was phase-locked to the slow γ in CA3, before (a) and after (b) the cut. Preventing CA3 inputs replaces the CA3-driven γ by faster γ in CA1. B, power spectra of recordings from the slice in A, before (grey line) and after the cut (black trace). C, same as B, but from a slice where two peaks were present in the power spectrum before the cut. The lack of CA3 inputs boosts the existing fast γ in CA1. D, example of the relation between γ power in CA3b and the fast γ power/slow γ power ratio for 125 1-s epochs recorded in CA1a of an intact slice with distinct fast γ in CA1. The ratio correlated inversely with CA3 γ power (Pearson's r = 0.52, P < 0.001). E, example of the rapid fluctuations in CA3 slow γ power (dashed line), CA1 fast γ power (grey line) and CA1 slow γ power (black line) recorded from an intact slice with distinct fast γ in CA1. The cross-correlogram shows the cross-correlation (over 600 s) between fluctuations in CA3 slow γ power (reference) and fluctuations in CA1 fast γ power (grey line) and CA1 slow γ power (black line) for the slice shown in the inset.

In 3 out of 53 intact slices the power spectrum of the recording from CA1a showed no distinguishable power peak in the gamma frequency band (criterion in Methods).

In 16 out of 53 slices the CA1a power spectrum had two distinct peaks (example in Fig. 7C, grey line), of which one had a dominant frequency similar to that in CA3 (34 ± 1 Hz), and a second had a dominant frequency of 45 ± 2 Hz. Recordings from subiculum in these slices failed to show gamma oscillations (data not shown).

The distribution of the ratio fast γ power (average power in the 40–70 Hz band) over slow γ power (average power in the 20–40 Hz band) along CA3–CA1 stratum pyramidale in these slices (Supplemental Fig. S2B), shows that the fast γ power proportion in CA1 γ increased with distance from CA3. The cross-correlation with CA3c γ dropped sharply with distance from CA3 (Supplemental Fig. S2C). The fast γ power proportion in CA1a decreased with time after carbachol application, associated with an increase in CA3b slow γ power with time (Supplemental Fig. S4).

For six slices with both fast γ and slow γ in CA1, the fast γ power/slow γ power ratio in CA1a (determined over 125 1-s epochs) correlated inversely with γ power in CA3b (Pearson's r = −0.63 ± 0.04, P < 0.001, example in Fig. 7D), suggesting that CA3 γ suppresses fast γ in CA1. This relationship was further assessed in these slices on a faster timescale by determining the correlation between power fluctuations in CA3 slow γ and power fluctuations in CA1 slow γ and CA1 fast γ (example in Fig. 7E inset). The maximum cross-correlation (with CA3 slow γ power as reference) was 0.34 ± 0.06 at −1 ± 2 ms for CA1 slow γ power (example in Fig. 7E, black line) and −0.18 ± 0.02 at 18 ± 2 ms (example in Fig. 7E, grey line). This indicates that slow γ power in CA1 is directly coupled to CA3 γ power and that fast γ power in CA1 decreases shortly after γ power in CA3 increased.

These observations suggest that rhythmic inputs from CA3 suppress fast γ in CA1, replacing them dynamically with a CA3-driven slow γ.

Fast gamma oscillations in CA1 after disconnection from CA3

To further test the effect of CA3 inputs on CA1 γ the Schaffer collaterals were cut (see Methods and Supplemental Fig. S2Ai) in intact slices with distinguishable power peak(s) in the gamma frequency band. In all slices with two discernible peaks in the CA1a power spectrum before the cut, the CA3-related power peak disappeared and fast γ power in CA1 increased to 211 ± 20% of pre-cut values (Student's t15 = 3.65, P = 0.002; example in Fig. 7C, black line), whereas the oscillation in CA3 was unaffected. The relationship between CA3 γ power and the fast γ power/slow γ power ratio disappeared (Pearson's r = 0.03 ± 0.07, n.s.), as did the cross-correlation between oscillatory activity in CA1 and that in CA3 (Supplemental Fig. S2C) and the correlation between γ power fluctuations in CA1 and CA3 (not shown). The fast γ power/slow γ power ratio along CA3–CA1 stratum pyramidale (Supplemental Fig. S2B), was now evenly distributed along CA1 stratum pyramidale. The changes in CA1 were most dramatic closer to CA3. In all slices without the fast γ peak before the cut, the CA3 γ-linked peak disappeared after the cut and 14 out of 16 slices now had a discernible fast γ peak. (example in Fig. 7Ab and B, black line). Additional cuts in proximal subiculum had no effect on the oscillation in CA1 in five slices tested (data not shown), suggesting that CA1 γ is not dependent on perforant path inputs.

These observations confirm that the intrinsic fast γ in CA1 is suppressed by the slow γ in CA3.

Rhythmic Schaffer collateral inputs suppress fast gamma oscillations in CA1

To test whether rhythmic CA3 inputs suppress fast γ in CA1 rhythmic, CA3 inputs were mimicked in CA1 minislices, by electrical stimulation of Schaffer collaterals in stratum radiatum of CA1c with 10-s trains of stimuli at different frequencies. Figure 8A shows the effect of a 35 Hz train of stimuli at 3 V, an intensity that evoked minimal population synaptic potentials, but strongly suppressed γ power in CA1b. In seven slices tested γ power (excluding stimulus artefact-induced power peaks at 35 Hz and 70 Hz) was reduced to 47 ± 10% (Student's t6 = 3.86, P = 0.002) of control values and the dominant frequency was reduced by 10.5 ± 0.5 Hz (Student's t6 = 10.58, P < 0.001; example in Fig. 8B). However, at 3 Hz the same intensity stimulus had no effect on γ power (102 ± 2% of control) or frequency (not shown). Figure 8C gives the γ power during stimulation (normalised to the γ power before stimulation) as a function of stimulus frequency and intensity, and shows that gamma frequency inputs into CA1 are especially effective in suppressing fast γ.

Figure 8.

Recordings were made in CA1b of CA1 minislices, with a stimulus electrode placed in stratum radiatum of CA1c (see Fig. 1A). A, example of the effect of a 3 V, 35 Hz stimulus train on carbachol-evoked fast γ. B, power spectra of the recording in A 10 s before (grey line) and 10 s during 35 Hz Schaffer collateral stimulation (black line). The stimulus artefact-induced power peaks at 35 Hz and 70 Hz (grey bars) have been omitted from the analysis. Stimulation at slow γ frequency suppresses fast γ and slows it down. C, CA1b γ power (normalised to control values) as a function of frequency and intensity of Schaffer collateral stimulation trains. Data give average for seven slices. D, example of waveform averages (time-zeroed to the stimuli) of the field potential in stratum pyramidale (grey line) and the trans-membrane potential of a pyramidal cell (black line) during a 3 V, 35 Hz stimulus train. Low-intensity Schaffer collateral stimulation evoked EPSPs curtailed by IPSPs. E, waveform averages of Im at −10 mV (black line, mainly IPSCs) and at −70 mV (grey line, mainly EPSCs, preceding the IPSC). F, waveform averages of Vm for a fast-spiking interneuron (stimuli that triggered firing were excluded) showed mainly EPSPs. Details as in D.

Schaffer collateral stimulation trains (35 Hz) at an intensity that suppressed γ power to ∼ 30% of control (3.6 ± 0.3 V), did not evoke firing in any of the 11 pyramidal cells held near firing threshold, but slightly hyperpolarised the membrane potential (recorded 20 ms before stimuli) by 1.0 ± 0.4 mV (Student's t10 = 2.53, P = 0.030). Trans-membrane potential waveform averages, time-zeroed at the stimulus, showed small (<1 mV) EPSPs curtailed by IPSPs (example in Fig. 8D) in most of the pyramidal cells, whereas in some only IPSPs were observed. Six pyramidal cells recorded under voltage clamp showed EPSC–IPSC sequences when held at −60 mV. For four cells the amplitude of the EPSC recorded at −80 mV was −35 ± 7 pA and the IPSC amplitude at 0 mV was 176 ± 22 pA (example in Fig. 8E). In contrast, a similar intensity stimulus caused large EPSPs (1.8 ± 0.2) that could trigger action potentials (at 3.9 ± 0.2 ms after the stimulus) in all four fast-spiking interneurons (example in Fig. 8F).

These observations confirm that rhythmic inputs from CA3 suppress fast γ in CA1 and suggest that this is due to feed-forward excitation of interneurons.

Discussion

In contrast to what was previously reported (Fisahn et al. 1998; Fellous & Sejnowski, 2000), isolated CA1 can generate fast coherent γ induced by cholinergic receptor activation. The intrinsic CA1 γ is based on a recurrent inhibitory loop and suppressed by gamma frequency input from CA3.

The CA1 gamma generating network

Fast gamma oscillations have previously been reported in CA1 minislices, induced by kainate or DHPG (Traub et al. 2003; Bibbig et al. 2007; Middleton et al. 2008; Kipiani, 2009). However, the kainate or DHPG concentrations required are sufficient to induce epileptiform activity in the intact hippocampal slice (Domenici et al. 1996; Rutecki et al. 2002) and it is unlikely that kainate or metabotropic glutamate receptor activation provides the driving force under physiological conditions. The EC50 of the carbachol concentration–γ power relationship for CA1 and dependence on muscarinic M1 receptor activation is similar to that reported for CA3 (Fisahn et al. 1998, 2002), where γ can also be induced by increasing endogenous acetylcholine release with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (Spencer et al. 2010). Together with the relatively rapid development upon addition of carbachol, this suggests that fast γ may occur in CA1 in response to physiological acetylcholine release in vivo, consistent with a septal drive of hippocampal γ (Cobb & Davies, 2005).

M1 receptor activation causes depolarisation of pyramidal cells (Fisahn et al. 2002) and interneurons in CA3 (Szabo et al. 2010) as well as cholecystokinin-expressing CA1 interneurons (Cea-del Rio et al. 2011). Pyramidal cell firing is directly followed by EPSPs in local fast-spiking interneurons that fire ∼2 ms after the pyramidal cells and in turn cause IPSCs in pyramidal cells and interneurons (Fig. 6). The dependence on GABAA receptors and the frequency decrease induced by thiopental (Traub et al. 1996; Pittson et al. 2004) confirm that intrinsic CA1 γ is based on inhibitory feedback, similar to that in CA3 (Fisahn et al. 1998; Mann et al. 2005). The dependence of CA1 γ on AMPA-type glutamate receptor activation is similar to that of spontaneous γ in CA3 (Pietersen et al. 2009) and carbachol-induced γ in CA3 where fast excitation is necessary for the synchronisation of the interneuron discharge (Fisahn et al. 1998; Traub et al. 2000; Mann et al. 2005). Compared with γ in CA3 (Atallah & Scanziani, 2009), gamma-related EPSCs recorded at the soma were very small in CA1 pyramidal cells, in line with the relatively sparse and weak recurrent connectivity in CA1 (Deuchars & Thomson, 1996). Consequently, recurrent excitation of pyramidal neurons is unlikely to play an important role in CA1 γ. These observations indicate that fast γ in CA1 is essentially of the pyramidal–interneuron network gamma (PING) type (Whittington et al. 2000). M2 receptor activation can cause a late, gradual increase in EPSC amplitude (Auerbach & Segal, 1996), which may explain the late increase in γ power by an increased recurrent excitation of interneurons.

The main rhythmic source that coincides with the IPSPs in pyramidal cells peaks about 4 ms after interneuron firing and is located in stratum pyramidale–oriens border. This suggests the involvement of basket cells and possibly axon-targeting interneurons (Baude et al. 2007) that can be activated recurrently (Sik et al. 1995) and are also known to drive γ in CA3 (Mann et al. 2005; Bartos et al. 2007). In the absence of further identification we can only suggest that the fast-spiking stratum pyramidale interneurons, firing from recurrent EPSPs, fulfil a similar role in the CA1 oscillation. Such interneurons express parvalbumin or cholecystokinin. Parvalbumin-expressing interneurons are mutually connected by synapses (Pawelzik et al. 1999; Baude et al. 2007) and by gap junctions (Fukuda & Kosaka, 2000; Baude et al. 2007), allowing the generation of interneuron network gamma (ING) oscillations (Whittington et al. 1995, 2000; Bartos et al. 2007). ING may therefore contribute to CA1 γ and facilitate zero-phase lag synchrony (Bartos et al. 2007) observed in the isolated CA1 network and in vivo (Penttonen et al. 1998). Similarly cholecystokinin-expressing interneurons form chemically and electrically coupled networks in CA1 (Iball & Ali, 2011). The IPSCs from cholecystokinin-expressing basket cells are suppressed by activity-dependent release of endocannabinoids, but this is dependent on interneuron firing rate and is absent at frequencies >20 Hz (Foldy et al. 2006). In anaesthetised rats cholecystokinin-expressing basket cells fire during the theta phase when CA1 pyramidal cells are active, whereas parvalbumin-expressing interneurons are active during the phase when pyramidal cells are quiet (Klausberger et al. 2005), suggesting involvement of cholecystokinin-expressing basket cells in the intrinsic feedback-driven γ in CA1.

CA1 gamma oscillations are faster than CA3 gamma oscillations

Despite similar basic network properties and oscillation power, CA1 γ was substantially faster than CA3 γ. The frequency of γ is dependent on IPSC amplitude (Traub et al. 1996; Atallah & Scanziani, 2009). However, the weak relationship between instantaneous frequency and IPSC amplitude (Fig. 5D), γ cycle amplitude (Supplemental Fig. S4) and γ power (Fig. 2A/B) cannot explain the difference with CA3 γ. The frequency of γ is set by the IPSC decay kinetics (Whittington et al. 1995; Traub et al. 1996; Fisahn et al. 1998; Heistek et al. 2010), as confirmed by the effect of thiopental. Interestingly in the presence of carbachol, the decay time of IPSCs recorded in CA1 pyramidal cells was shorter than that in CA3 pyramidal cells (Heistek et al. 2010), which may explain the higher γ oscillation frequency. In addition, since the γ frequency is dependent on tonic excitatory drive to interneurons (Traub et al. 1996; Mann & Mody, 2010) and correlates with CA1 interneuron firing frequency (Ahmed & Mehta, 2012), the tonic depolarizing drive of fast-spiking interneurons involved in CA1 γ may be a stronger than in CA3. This dependence would imply a contribution of ING to fast γ in CA1, as was suggested for the fast γ in the medial entorhinal cortex (Cunningham et al. 2003), and supported by the reduction of CA1 γ frequency to that of slow γ by increasing tonic GABAA-ergic inhibition of interneurons with THIP (Mann & Mody, 2010).

CA3 suppression of CA1 gamma oscillation

In the intact slice fast CA1 γ was suppressed by CA3 γ, dependent on the distance from CA3 (Supplemental Fig. S2B). This suppression and the transition to slow γ frequencies could be mimicked in the isolated CA1 slice by low-intensity stimulation of Shaffer collaterals at slow γ frequencies, as well by THIP.

During CA3-driven γ CA1 output is low (Bibbig et al. 2007; Zemankovics et al. 2013), which was confirmed by the absence of action potential back propagation in the CSD in the intact slice (Fig. 3C) and by the absence of pyramidal cell firing during slow γ frequency stimulation, which did activate fast-spiking interneurons. Basket cells in CA1 can be activated reliably by CA3 inputs at stimulus intensities when only a few pyramidal cells are activated (Fricker & Miles, 2000; Zemankovics et al. 2013). Similarly, during CA3-driven γ in CA1, basket cells operate in feed-forward mode and CA1 pyramidal cells fire (if at all) after CA1 interneurons in vitro (Bibbig et al. 2007) and in vivo (Penttonen et al. 1998; Csicsvari et al. 2003; Tukker et al. 2007; Carr et al. 2012). This suggests that the slow γ frequency input from CA3 imposes a break on CA1 pyramidal cell firing and hence the intrinsic feed-back interneuron-mediated fast γ (Zemankovics et al. 2013). In addition, spillover of GABA acting on extra-synaptic δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors may increase tonic inhibition of interneurons, causing the intrinsic oscillation to slow down (Mann & Mody, 2010).

Functional implications

In addition to the CA3 γ drive, CA1 receives γ frequency inputs from the entorhinal cortex (Bragin et al. 1995; Csicsvari et al. 2003), which can reduce the effectiveness of CA3 inputs through stratum lacunosum/moleculare interneuron activation (Dvorak-Carbone & Schuman, 1999; Remondes & Schuman, 2002). This may allow the intrinsic fast γ in CA1 to emerge and to phase-lock to the fast γ in the medial entorhinal cortex, e.g. through direct activation of parvalbumin-expressing basket and axon-targeting cells in CA1 (Kiss et al. 1996). Lesion of the entorhinal cortex increases the CA3–CA1 coupling (Bragin et al. 1995), which suggests that CA3 and the medial entorhinal cortex compete to govern the gamma synchronisation in CA1, either by suppressing intrinsic fast γ and forcing CA1 to follow CA3 slow γ or by suppressing CA3 inputs and allow intrinsic fast γ to resonate with fast γ in the medial entorhinal cortex. The resulting phase-locking would promote “neuronal communication through neuronal coherence” (Womelsdorf et al. 2007) between CA1 and CA3, and between CA1 and the medial entorhinal cortex respectively.

The functional coupling between CA3 γ and CA1 γ and between entorhinal cortex and CA1 γ is dynamically modulated in the behaving rat. It varies with different phases of a maze task (Montgomery & Buzsaki, 2007) and different behavioural states (Csicsvari et al. 2003; Montgomery et al. 2008; Senior et al. 2008; Colgin et al. 2009; Carr et al. 2012; Carr & Frank, 2012). Furthermore, it is modulated by the theta rhythm; the firing of the pyramidal cell population active in the early theta phase is thought to be paced by CA3 γ through feed-forward activation of parvalbumin-expressing interneurons and bi-stratified interneurons (Tukker et al. 2007), whereas pyramidal cells active in the late theta phase are gamma-modulated by local interneurons (Senior et al. 2008; Colgin et al. 2009), probably cholecystokinin-expressing basket cells (Klausberger et al. 2005).

Our data support the hypothesis that CA3 and the medial entorhinal cortex compete to dynamically switch the γ mode of CA1, thus allowing for routing and segregating of information streams involved in the encoding, storage and recall of memory traces (Senior et al. 2008; Colgin et al. 2009; Colgin & Moser, 2010; Carr et al. 2012; Carr & Frank, 2012).

Key points

The synchronisation of neuronal activity at gamma frequencies (30–100 Hz) could determine the effectiveness of neuronal communication.

Gamma oscillations in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in vitro was thought to be dependent on gamma oscillations generated in area CA3, but in vivo CA1 can generate gamma oscillations independently.

In this study we found that activating acetylcholine receptors induced stable gamma oscillations in the CA1 local network isolated in slices in vitro that were faster than those in CA3, but relied on similar neuronal circuitry involving feedback inhibition.

Gamma frequency inputs from CA3 (spontaneous in intact hippocampal slices or stimulated in isolated CA1) can suppress the local fast gamma oscillation in CA1 and force it to adopt the slower CA3 oscillation through feed-forward inhibition.

This modulation could allow CA1 to alternate between effective communication with the entorhinal cortex and CA3, which may regulate memory encoding and memory recall phases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gareth Morris for advice on circular statistics.

Glossary

- aCSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- APV

D-(-)-2-Amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid

- ATPA

(RS)-2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-tert-butylisoxazol-4-yl

- BMI

bicuculline methiodide

- CSD

current-source density

- CA1

cornu ammonis area 1

- CA3

cornu ammonis area 3

- EPSC

excitatory postsynaptic current

- γ

gamma oscillations

- FIR

finite impulse response

- ING

interneuron network gamma

- IPSC

inhibitory postsynaptic current

- MCPG

(S)-α-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine

- PING

pyramidal–interneuron network gamma

- SYM 2206

(±)-4-(4-aminophenyl)-1,2-dihydro-1-methyl-2-propylcarbamoyl-6,7-methylenedioxyphthalazine

- THIP

4,5,6,7,-tetrahydroixoxazolo[5,4-c]pyridine-3-ol hydrochloride

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

M.V. designed the study, A.J.N.P, P.W., N.H.-V. and J.W. performed the experiments at the University of Birmingham, using equipment owned by J.G.R.J. M.V. and J.G.R.J. were the primary writers, while all authors contributed to critical interpretation of data, edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council through the Doctoral Training Account of the University of Birmingham.

References

- Ahmed OJ, Mehta MR. Running speed alters the frequency of hippocampal gamma oscillations. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7373–7383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5110-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atallah BV, Scanziani M. Instantaneous modulation of gamma oscillation frequency by balancing excitation with inhibition. Neuron. 2009;62:566–577. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach JM, Segal M. Muscarinic receptors mediating depression and long-term potentiation in rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1996;492:479–493. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos M, Vida I, Jonas P. Synaptic mechanisms of synchronized gamma oscillations in inhibitory interneuron networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:45–56. doi: 10.1038/nrn2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baude A, Bleasdale C, Dalezios Y, Somogyi P, Klausberger T. Immunoreactivity for the GABAA receptor alpha1 subunit, somatostatin and Connexin36 distinguishes axoaxonic, basket, and bistratified interneurons of the rat hippocampus. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:2094–2107. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibbig A, Middleton S, Racca C, Gillies MJ, Garner H, LeBeau FE, Davies CH, Whittington MA. Beta rhythms (15–20 Hz) generated by nonreciprocal communication in hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:2812–2823. doi: 10.1152/jn.01105.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A, Jandó G, Nádasdy Z, Hetke J, Wise K, Buzsáki G. Gamma (40–100 Hz) oscillation in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. J Neurosci. 1995;15:47–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00047.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr MF, Frank LM. A single microcircuit with multiple functions: state dependent information processing in the hippocampus. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2012;22:704–708. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr MF, Karlsson MP, Frank LM. Transient slow gamma synchrony underlies hippocampal memory replay. Neuron. 2012;75:700–713. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cea-del Rio CA, Lawrence JJ, Erdelyi F, Szabo G, McBain CJ. Cholinergic modulation amplifies the intrinsic oscillatory properties of CA1 hippocampal cholecystokinin- positive interneurons. J Physiol. 2011;589:609–627. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.199422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb SR, Davies CH. Cholinergic modulation of hippocampal cells and circuits. J Physiol. 2005;562:81–88. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.076539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgin LL, Denninger T, Fyhn M, Hafting T, Bonnevie T, Jensen O, Moser MB, Moser EI. Frequency of gamma oscillations routes flow of information in the hippocampus. Nature. 2009;462:353–357. doi: 10.1038/nature08573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgin LL, Moser EI. Gamma oscillations in the hippocampus. Physiology. 2010;25:319–329. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00021.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csicsvari J, Jamieson B, Wise KD, Buzsáki G. Mechanisms of gamma oscillations in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. Neuron. 2003;37:311–322. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham MO, Davies CH, Buhl EH, Kopell N, Whittington MA. Gamma oscillations induced by kainate receptor activation in the entorhinal cortex in vitro. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9761–9769. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-30-09761.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuchars J, Thomson AM. CA1 pyramid-pyramid connections in rat hippocampus in vitro: dual intracellular recordings with biocytin filling. Neuroscience. 1996;74:1009–1018. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00251-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson R, Awaiz S, Whittington MA, Lieb WR, Franks NP. The effects of general anaesthetics on carbachol-evoked gamma oscillations in the rat hippocampus in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44:864–872. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenici MR, Longo R, Sagratella S. 7-Chlorokynurenic acid prevents in vitro epileptiform and neurotoxic effects due to kainic acid. Gen Pharmacol. 1996;27:113–116. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak-Carbone H, Schuman EM. Patterned activity in stratum lacunosum moleculare inhibits CA1 pyramidal neuron firing. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:3213–3222. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellous J-M, Sejnowski TJ. Cholinergic induction of oscillations in the hippocampal slice in the slow (0.5–2 Hz), theta (5–12 Hz) and gamma (35–0 Hz) bands. Hippocampus. 2000;10:187–197. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(2000)10:2<187::AID-HIPO8>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisahn A, Pike FG, Buhl EH, Paulsen O. Cholinergic induction of network oscillations at 40 Hz in the hippocampus in vitro. Nature. 1998;394:186–189. doi: 10.1038/28179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisahn A, Yamada M, Duttaroy A, Gan JW, Deng CX, McBain CJ, Wess J. Muscarinic induction of hippocampal gamma oscillations requires coupling of the M1 receptor to two mixed cation currents. Neuron. 2002;33:615–624. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foldy C, Neu A, Jones MV, Soltesz I. Presynaptic, activity-dependent modulation of cannabinoid type 1 receptor-mediated inhibition of GABA release. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1465–1469. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4587-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker D, Miles R. EPSP amplification and the precision of spike timing in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2000;28:559–569. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries P, Nikolic D, Singer W. The gamma cycle. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T, Kosaka T. Gap junctions linking the dendritic network of GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1519–1528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01519.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heistek TS, Timmerman AJ, Spijker S, Brussaard AB, Mansvelder HD. GABAergic synapse properties may explain genetic variation in hippocampal network oscillations in mice. Front Cell Neurosci. 2010;4:18. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2010.00018. DOI: 10.3389/fncel.2010.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iball J, Ali AB. Endocannabinoid release modulates electrical coupling between CCK cells connected via chemical and electrical synapses in CA1. Front Neural Circuits. 2011;5:17. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2011.00017. DOI: 10.3389/fncir.2011.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O, Lisman JE. Hippocampal sequence-encoding driven by a cortical multi-item working memory buffer. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kipiani E. OLM interneurons are transiently recruited into field gamma oscillations evoked by brief kainate pressure ejections onto area CA1 in mice hippocampal slices. Georgian Med News. 2009;167:63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss J, Buzsáki G, Morrow JS, Glantz SB, Leranth C. Entorhinal cortical innervation of parvalbumin-containing neurons (Basket and Chandelier cells) in the rat Ammon's horn. Hippocampus. 1996;6:239–246. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:3<239::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Marton LF, O'Neill J, Huck JH, Dalezios Y, Fuentealba P, Suen WY, Papp E, Kaneko T, Watanabe M, Csicsvari J, Somogyi P. Complementary roles of cholecystokinin- and parvalbumin-expressing GABAergic neurons in hippocampal network oscillations. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9782–9793. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3269-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman F, Peloquin P, Leung LS. Apical and basal orthodromic population spikes in hippocampal CA1 in vivo show different origins and patterns of propagation. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:2435–2444. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.5.2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J. The theta/gamma discrete phase code occurring during the hippocampal phase precession may be a more general brain coding scheme. Hippocampus. 2005;15:913–922. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann EO, Mody I. Control of hippocampal gamma oscillation frequency by tonic inhibition and excitation of interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:205–212. doi: 10.1038/nn.2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann EO, Suckling JM, Hajos N, Greenfield SA, Paulsen O. Perisomatic feedback inhibition underlies cholinergically induced fast network oscillations in the rat hippocampus in vitro. Neuron. 2005;45:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton S, Jalics J, Kispersky T, LeBeau FE, Roopun AK, Kopell NJ, Whittington MA, Cunningham MO. NMDA receptor-dependent switching between different gamma rhythm-generating microcircuits in entorhinal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18572–18577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809302105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SM, Buzsaki G. Gamma oscillations dynamically couple hippocampal CA3 and CA1 regions during memory task performance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14495–14500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701826104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SM, Sirota A, Buzsaki G. Theta and gamma coordination of hippocampal networks during waking and rapid eye movement sleep. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6731–6741. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1227-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oke OO, Magony A, Anver H, Ward PD, Jiruska P, Jefferys JGR, Vreugdenhil M. High-frequency gamma oscillations coexist with low-frequency gamma oscillations in the rat visual cortex in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:1435–1445. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palhalmi J, Paulsen O, Freund TF, Hajos N. Distinct properties of carbachol- and DHPG-induced network oscillations in hippocampal slices. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelzik H, Bannister AP, Deuchars J, Llia M, Thomson AM. Modulation of bistratified cell IPSPs and basket cell IPSPs by pentobarbitone sodium, diazepam and Zn2+: dual recordings in slices of adult rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:3552–3564. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penttonen M, Kamondi A, Acsady L, Buzsáki G. Gamma frequency oscillation in the hippocampus of the rat: intracellular analysis in vivo. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:718–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietersen AN, Patel N, Jefferys JGR, Vreugdenhil M. Comparison between spontaneous and kainate-induced gamma oscillations in the mouse hippocampus in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:2145–2156. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittson S, Himmel AM, MacIver MB. Multiple synaptic and membrane sites of anesthetic action in the CA1 region of rat hippocampal slices. BMC Neurosci. 2004;5:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-5-52. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2202-5-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remondes M, Schuman EM. Direct cortical input modulates plasticity and spiking in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nature. 2002;416:736–740. doi: 10.1038/416736a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutecki PA, Sayin U, Yang Y, Hadar E. Determinants of ictal epileptiform patterns in the hippocampal slice. Epilepsia. 2002;43(Suppl. 5):179–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.43.s.5.34.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer AT, Angelo K, Spors H, Margrie TW. Neuronal oscillations enhance stimulus discrimination by ensuring action potential precision. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior TJ, Huxter JR, Allen K, O'Neill J, Csicsvari J. Gamma oscillatory firing reveals distinct populations of pyramidal cells in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2274–2286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4669-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sik A, Penttonen M, Ylinen A, Buzsáki G. Hippocampal CA1 interneurons: An in vivo intracellular labeling study. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6651–6665. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06651.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JP, Middleton LJ, Davies CH. Investigation into the efficacy of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, donepezil, and novel procognitive agents to induce gamma oscillations in rat hippocampal slices. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo GG, Holderith N, Gulyas AI, Freund TF, Hajos N. Distinct synaptic properties of perisomatic inhibitory cell types and their different modulation by cholinergic receptor activation in the CA3 region of the mouse hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:2234–2246. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07292.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Bibbig A, Fisahn A, LeBeau FEN, Whittington MA, Buhl EH. A model of gamma-frequency network oscillations induced in the rat CA3 region by carbachol in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:4093–4106. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Cunningham MO, Gloveli T, LeBeau FE, Bibbig A, Buhl EH, Whittington MA. GABA-enhanced collective behavior in neuronal axons underlies persistent gamma-frequency oscillations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11047–11052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934854100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Whittington MA, Colling SB, Buzsáki G, Jefferys JGR. Analysis of gamma rithms in the rat hippocampus in vitro and in vivo. J Physiol. 1996;493:471–484. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tukker JJ, Fuentealba P, Hartwich K, Somogyi P, Klausberger T. Cell type-specific tuning of hippocampal interneuron firing during gamma oscillations in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8184–8189. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1685-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreugdenhil M, Bracci E, Jefferys JG. Layer-specific pyramidal cell oscillations evoked by tetanic stimulation in the rat hippocampal area CA1 in vitro and in vivo. J Physiol. 2005;562:149–164. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington MA, Traub RD, Jefferys JGR. Synchronized oscillations in interneuron networks driven by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation. Nature. 1995;373:612–615. doi: 10.1038/373612a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington MA, Traub RD, Kopell N, Ermentrout B, Buhl EH. Inhibition-based rhythms: experimental and mathematical observations on network dynamics. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000;38:315–336. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(00)00173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womelsdorf T, Schoffelen JM, Oostenveld R, Singer W, Desimone R, Engel AK, Fries P. Modulation of neuronal interactions through neuronal synchronization. Science. 2007;316:1609–1612. doi: 10.1126/science.1139597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemankovics R, Veres JM, Oren I, Hajos N. Feedforward inhibition underlies thepropagation of cholinergically induced gamma oscillations from hippocampal CA3 to CA1. J Neurosci. 2013;33:12337–12351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3680-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.