Abstract

Regulatory T cell (Treg) immunotherapy is a promising strategy for the treatment of graft rejection responses and autoimmune disorders. Our and other laboratories have shown that the transfer of highly purified CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ natural Treg can prevent lethal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation across both major and minor histocompatibility barriers. However, recent evidence suggests that the Treg suppressive phenotype can become unstable, a phenomenon that can culminate in Treg conversion into IL-17–producing cells. We hypothesized that the intense proinflammatory signals released during an ongoing alloreaction might redirect a fraction of the transferred Treg to the Th17 cell fate, thereby losing immunosuppressive potential. We therefore sought to evaluate the impact of Il17 gene ablation on Treg stability and immunosuppressive capacity in a major MHC mismatch model. We show that although Il17 gene ablation results in a mildly enhanced Treg immunosuppressive ability in vitro, such improvement is not observed when IL-17–deficient Treg are used for GVHD suppression in vivo. Similarly, when we selectively blocked IL-1 signaling in Treg, that was shown to be necessary for Th17 conversion, we did not detect any improvement on Treg-mediated GVHD suppressive ability in vivo. Furthermore, upon ex vivo reisolation of transferred wild-type Treg, we detected little or no Treg-mediated IL-17 production upon GVHD induction. Our results indicate that blocking Th17 conversion does not affect the GVHD suppressive ability of highly purified natural Treg in vivo, suggesting that IL-17 targeting is not a valuable strategy to improve Treg immunotherapy after hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Keywords: Regulatory T cells, Graft-versus-host disease, Th17 cells, Bone marrow transplantation, Allogeneic hematopoietic cell, transplantation, In vivo bioluminescence

INTRODUCTION

Regulatory T cell (Treg) immunotherapy is a promising strategy for the therapeutic control of both autoimmune diseases and graft-versus-host responses. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg cells are a key immunoregulatory cell population involved in the maintenance of immune tolerance [1,2]. The transfer of highly purified Treg has demonstrated promising results in preclinical models for both the control of autoimmunity [3,4], and the induction of transplantation tolerance [5–8]. In particular, after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), we and others have shown that Treg successfully prevent lethal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) induced by donor-derived conventional T cells (CD4+ and CD8+ T cells; Tcon) in multiple models across both major and minor histocompatibility barriers [9–18].

GVHD is a potentially life-threatening complication after HCT, where Tcon of alloreactive specificities infiltrate and destroy healthy target organs such as the liver, gastrointestinal tract, and skin. Although immunomodulation is necessary to control adverse GVHD reactions, an effective immune response is required for successful tumor eradication, termed the graft-versus-tumor effect, and for the prevention of opportunistic infections. Notably, when cotransferred into recipient mice with established leukemia or lymphoma, Treg suppressed Tcon proliferation and prevented lethal GVHD, while preserving graft-versus-tumor activity [12,14,15,17]. Furthermore, extension of these findings to the clinic using Treg from haploidentical or umbilical cord blood donors has recently shown promising results [19,20].

The molecular basis for the suppressive activity of Treg is still a matter of debate. An increasing body of evidence suggests that, under the influence of certain inflammatory signals, the Treg suppressive phenotype can become unstable, and that Treg are capable of converting into IL-17–producing proinflammatory cells in vivo and in vitro [21–30]. For example, Foxp3+ IL-17+ intermediates have been detected both in vivo and ex vivo in murine models for autoimmune encephalomyelitis [29] and diabetes [31]. While such plasticity of the Treg phenotype is likely to be beneficial during an ongoing infection, it represents a major threat for the stability of Treg suppressive function following Treg immunotherapy.

The role of IL-17 itself on GVHD progression is currently controversial. In different experimental models, IL-17 has been reported to be not necessary unecessary [32], promoting [33], or ameliorating GVHD [34]. IL-17 production by Tcon does not seem to represent a major pathogenic factor, and the absence of donor-derived IL-17 was shown to exacerbate rather than ameliorate GVHD across major histocompatibility barriers, due to increased Th1 differentiation [34]. We focused on evaluating the role of the Il17 gene and IL-17 cytokine production on Treg phenotypic stability and immunosuppressive ability in vivo and in vitro, in an effort to improve Treg function for the control of GVHD in vivo. Indeed, IL-17 production by Treg has been consistently associated with a loss of their suppressive phenotype [26,35,36]. Thus, we employed in vitro and in vivo systems to assess the role of IL-17 targeting on Treg function for the suppression of allospecific T cell activation.

METHODS

Mice

Il17a knockout mice were previously described [32] and were a kind gift of Dr. DeFu Zeng, City of Hope National Medical Center (Duarte, CA), with permission of Dr. Y. Iwakura, Institute for Medical Science (Tokyo, Japan). Il1r1 KO mice (strain B6.129S7-Il1r1tm1Imx/J), WT C57BL/6 (Thy1.2+), C57BL/6 Thy1.1+, C57BL/6 CD45.1+, and WT Balb/c mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Sacramento, CA). luc+ C57BL/6-L2G85 mice were previously described [37,38]. All experimental animals were housed at the Stanford University animal facility and used under Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care (APLAC)-approved protocols.

Mixed Lymphocyte Reactions

Balb/c splenocytes were irradiated with 30 Gy and used as stimulators at a 2:1 ratio with mixed CD4+ and CD8+ responder cells. CD4+ and CD8+ responders were purified from pooled spleens and lymph nodes of C57BL/6 mice with the aid of anti-mouse-CD4 (clone L3T4) and anti-mouse-CD8 (Ly-2) magnetically labeled antibodies and Magnetic Cell Separation (MACS) technology (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Irradiated stimulator cells, responder cells, and different doses of highly purified Tregs, which were sorted from either wild-type (WT) or IL-17 KO C57BL/6 mice, were plated in a flat-bottom 96-well plate. Following 4 days of incubation, the cells were pulsed with 1 μCi per well of [3H]-thymidine and harvested 16 to 18 hours later onto filter membranes with the aid of a Wallac harvester (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA). The amount of incorporated [3H]-thymidine was measured with a Wallac Betaplate counter (Perkin-Elmer).

GVHD Model and Assessment

Balb/c (H-2d) recipients and C57/Bl/6 (H-2b) donors were used as previously described [9,15–17]. Animals were prepared with a lethal dose of total body radiation (consisting of 2 doses of 4 Gy, 4 to 6 hours apart), followed by donor-derived 5 × 106 T cell–depleted bone marrow (TCD-BM) on day 0. GVHD was induced by the injection of 5 × 105 magnetically purified CD4+ and CD8+ luc+ Tcon on day 2 at a 2:1 CD4-to-CD8 ratio. CD4+ and CD8+ luc+ Tcon were purified from pooled spleens and lymph nodes of luc+ C57BL/6 mice with the aid of anti-mouse-CD4 (clone L3T4) and anti-mouse-CD8 (Ly-2) magnetically labeled antibodies and MACS cell separation technology (Miltenyi Biotec). The experimental animals were assessed for Tcon proliferation, survival, and weight scores on the indicated time points.

Bioluminescent Cell Imaging System

luc+ CD4+ and CD8+ Tcon were transferred into the MHC-mismatched recipients 2 days after TCD-BM and Treg injections. The experimental animals were monitored at the indicated time points following the injection of the luciferase substrate, luciferin. The number of luc+ cells is directly proportional to the number of photons detected by the bioluminescent imaging (BLI) system (IVIS 7, IVIS 29, or IVIS Spectrum charge-coupled device imaging system; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA), allowing for an accurate quantification of Tcon proliferation, which gives a measure of ongoing GVHD [17,39]. Images were analyzed with Living Image software 2.5 (Xenogen).

Treg Purification

Treg were first enriched from pooled spleens and lymph nodes of donor mice via allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD25 antibodies (clone PC61.5; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and magnetically labeled anti-APC beads (MACS cell separation technology; Miltenyi Biotec). Subsequently, Treg were highly purified as CD4+CD25bright cells via fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) (BD FACSAria III, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and confirmed to be more than 98% CD4+CD25brightFoxp3+ by intracellular Foxp3 staining (clones GK1.5, PC61.5, and FJK-16s for CD4, CD25, and Foxp3, respectively).

Intracellular Cytokine Assessment

Balb/c recipient mice received C57BL/6-derived TCD-BM and highly purified Treg intravenously on day 0, followed by Tcon infusion on day 2 as described above. Recipient mice were sacrificed 7 and 14 days following Treg transfer. Mesenteric lymph nodes, pooled peripheral lymph nodes (cervical, brachial, axillary, and inguinal nodes), and spleen were isolated, and single cell preparations were restimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (40 ng/mL) and ionomycin (92 μM) in presence of monensin (2 μM, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 5 hours. The cells were then stained for surface markers, fixed, permeabilized, and assessed for intracellular IL-17A and Foxp3 expression with the aid of a mouse Foxp3 staining kit (eBioscience). The following antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA), eBioscience, or BioLegend (San Diego, CA): CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53–6.7), CD45.1 (A20), Thy-1.1 (OX-7), CD25 (PC61), H-2Kb (AF6-88.5), Foxp3 (FJK-16s), IL-17 (TC11-18H10.1), and IFN-γ (XMG1.2). Transferred Treg were identified as live CD4+H-2b+Thy1.2+CD45.1− cells, whereas Tcon were identified as Th1.1+CD45.1+H-2b+ cells. Residual recipient hematopoietic cells were excluded as Th1.1−CD45.1−H-2d+, and donor BM-derived cells were gated out as Thy1.1+CD45.1−H-2b+ cells. FACS analysis was performed with an LSR II (BD Biosciences).

Statistical Analysis

Differences in Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed with the log rank test. All other comparisons were performed with the 2-tailed Student t-test. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

IL-17–Deficient Treg Show a Mildly Enhanced Suppressive Ability on the Proliferation of Alloreactive T Cells In Vitro

Treg have been demonstrated to convert into IL-17–producing cells under different inflammatory conditions [21–30]. We hypothesized that a percentage of Treg or a specific Treg subset that are exposed to intense inflammatory signals released during ongoing GVHD in vivo might be redirected to a Th17 cell fate, thus losing immunosuppressive potential. Therefore, we reasoned that Treg purified from Il17a knockout (IL-17 KO) donor mice would have enhanced immunomodulatory capacity compared with WT Treg, given their inability to produce IL-17A (more commonly referred to as IL-17).

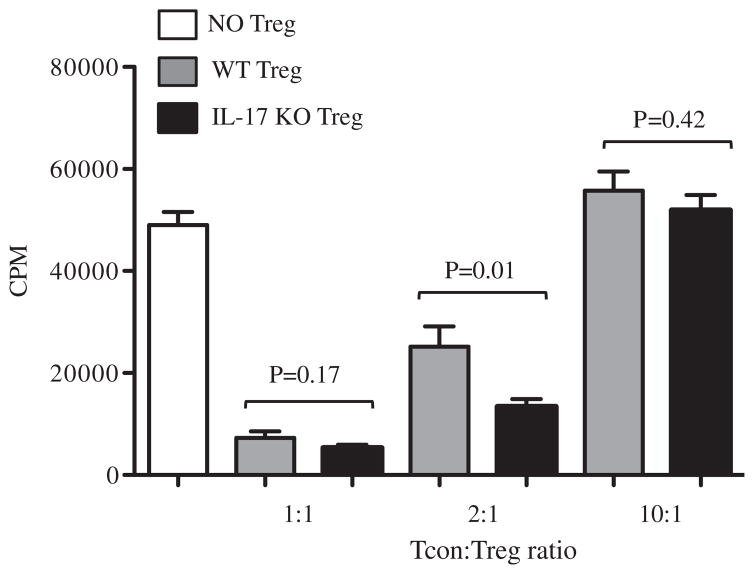

We first compared WT and IL-17 KO Treg for the ability to suppress allogeneic Tcon proliferation in a mixed lymphocyte reaction in vitro. Balb/c (H-2d) derived irradiated stimulators and C57BL/6 (H-2b) derived responders were incubated in the presence or absence of graded doses of WT and IL-17 KO Treg. Four days later, Tcon proliferation was measured by [3H]-thymidine incorporation. Both WT and IL-17 KO Treg were efficient in controlling Tcon proliferation at a 1:1 Tcon/Treg ratio, and such ability was lost at a high 10:1 ratio, as expected (Figure 1). Interestingly, Treg lacking the IL17 gene demonstrated a 2-fold increase in the suppression of allogeneic Tcon proliferation compared with WT Treg at the intermediate Tcon/Treg ratio of 2:1.

Figure 1.

IL-17 KO Tregs have mildly enhanced suppressive ability on the proliferation of allogeneic T cells in vitro. Tregs from WT or IL-17 KO donors were compared for their suppressive ability in an MLR in vitro. Irradiated total splenocytes from Balb/c mice (d/d haplotype) were used as stimulators (S) and CD4+ and CD8+ WT C57BL/6 mice (b/b haplotype) were used as responders (R) at a fixed 2:1 S/R ratio. At the same time, Treg isolated from either WT or IL-17 KO donors (both on a C57BL/6 background, b/b haplotype) were added at 1:1, 2:1, and 10:1 Tcon/Treg ratios. After 4 days of co-incubation, the cells were pulsed with 1 μCi [3H]-thymidine per well for 16 to 18 hours and Tcon proliferation was quantified by measuring [3H]-thymidine incorporation. The bar graphs are representative of 2 different MLRs combined. Probability values are as indicated, representing differences in suppressive function of the 2 populations of Treg.

WT and IL-17 KO Treg Have Comparable GVHD Suppressive Ability In Vivo

We purified Treg from both WT and IL-17 KO mice for the comparison of their GVHD suppressive ability in vivo in dose titration experiments. Similarly to our in vitro experiments, we tested the GVHD suppressive ability of Treg across major histocompatibility barriers. Typically, we found that a dose of 5 × 105 Treg injected i.v. on day 0 is effective in suppressing GVHD [15,17]. In preliminary experiments, we used a high (1:1 Tcon/Treg ratio), intermediate (2:1 Tcon/Treg ratio), and low (4:1 Tcon/Treg ratio) dose of transferred Treg to monitor differences in Tcon proliferation and GVHD progression demonstrating a dose–response relationship between the number of Treg injected and overall survival (data not shown).

To explore the role of IL-17 in Treg function, Balb/c recipients underwent lethal irradiation and were transplanted with 5 ×106 TCD-BM and either 5 ×105 (1:1 Tcon/Treg ratio) or 1.25 × 105 Treg (4:1 Tcon/Treg ratio) isolated from either WT or IL-17 KO C57Bl/6 donors. To monitor ongoing GVHD, our laboratory has developed a bioluminescent imaging (BLI) system that allows the in vivo visualization of T cell homing and proliferation over time, without the necessity of killing the experimental animals [17,39]. Specifically, 2 days after the transfer of the TCD-BM and Treg, the recipient animals received .5 × 106 CD4+ and CD8+ allogeneic Tcon purified from luciferase+ (luc+) C57Bl/6 donors. Importantly, the number of photons emitted by the luc+ Tcon was shown to be directly proportional to the number of Tcon present in vivo [17,39]. Thus, our in vivo BLI system provides a quantitative assessment of T cell proliferation at different time points in vivo, which gives a measure of ongoing GVHD.

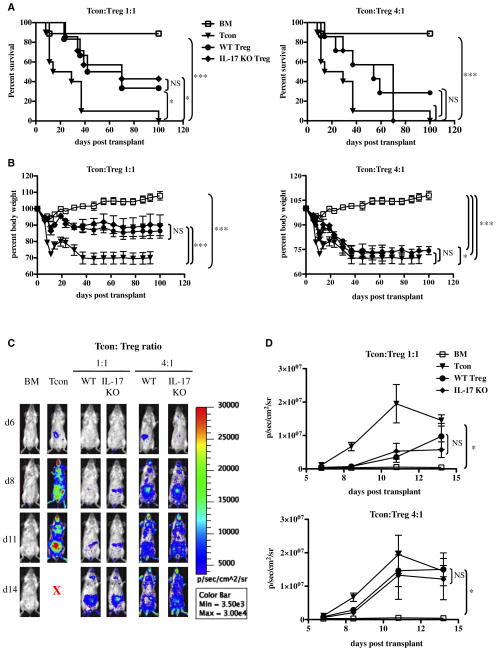

WT and IL-17 KO Treg demonstrated comparable purity (>98% Foxp3+ cells) and similar expression levels of both Foxp3 and the Treg marker CD25 (IL-2Rα chain) (Supplemental Figure 1). IL-17 KO Tregs had identical GVHD suppressive ability when compared with WT Treg in vivo (Figure 2A,B). The Tcon-derived BLI signal was similarly suppressed by WT and IL-17 KO Treg at both the 1:1 and 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratios (Figure 2C,D), the latter ratio showing a significant loss in the GVHD suppressive ability by both sets of Treg in the in vivo setting.

Figure 2.

WT and IL-17 KO Treg have a comparable GVHD suppressive ability in vivo. (A) Survival curves of recipient mice transplanted with BM alone (BM), BM on day 0 + Tcon on day 2 (Tcon group), and BM cotransplanted with either WT or IL-17 KO Treg, followed by Tcon transplantation 2 days later (Treg group). Both 1:1 and 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratios are shown. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (BM n = 9, Tcon n = 10; WT Tcon/Treg 1:1 n = 6; WT Tcon/Treg 4:1 n = 7; IL-17 KO Tcon/Treg 1:1 n = 7; IL-17 KO Treg 4:1 n = 7). Statistical differences between survival curves were calculated with a log rank test. For the 1:1 Tcon/Treg ratio: Tcon vs. WT Treg P =.05; Tcon vs. IL-17 KO Treg P =.02; BM vs. Tcon P =.0002; WT Treg vs. IL-17 KO Treg P = NS; BM vs. WT Treg P =.04; BM vs. IL-17 KO Treg P =.08. For the 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratio: BM vs. Tcon P =.0002; Tcon vs. WT Treg P =.06; Tcon vs. IL-17 KO Treg P = NS; WT Treg vs. IL-17KO Treg P = NS; BM vs. WT Treg P =.04; BM vs. IL-17 KO Treg P =.08. (B) Weight curves of the same animals as in (A). For consistency, the last measurement of each diseased animal was kept in the analysis until the last mouse in each given group expired Statistical differences between groups were calculated with a 2-tailed unpaired Student t-test. For the 1:1 Tcon/Treg ratio: BM vs. Tcon P <.0001; Tcon vs. WT Treg P <.0001; Tcon vs. IL-17 KO Treg P <.0001; BM vs. WT Treg P <.0001; BM vs. IL-17 KO Treg P <.0001. For the 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratio: BM vs. Tcon P <.0001; Tcon vs. WT Treg P =.13; Tcon vs. IL-17 KO Treg P =.03; WT Treg vs. IL-17 KO Treg P =.34; BM vs. WT Treg P <.0001; BM vs. IL-17 KO Treg P <.0001. (C) In vivo BLI images of representative animals showing the luminescent signal (in photons per second) derived from the allogeneic luc+ Tcon during acute GVHD, in the presence or absence of WT and IL-17-KO Tregs. Both 1:1 and 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratios are shown. (D) Quantification of the in vivo BLI data from luc+ Tcon as a measure of ongoing GVHD. Shown are 1:1 and 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratios. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (BM n = 9; Tcon n = 10; WT Tcon/Treg 1:1 n = 6; IL-17 Tcon/Treg 1:1 n = 7; WT Tcon/Treg 4:1 n = 7; IL-17 KO Tcon/Treg 4:1 n = 7). Statistical differences between curves were calculated with a 2-tailed Student t-test. For the 1:1 Tcon/Treg ratio: BM vs. Tcon P =.05; WT Treg vs. IL-17 KO Treg P =.84; Tcon vs. WT Treg P =.19; Tcon vs. IL-17 KO Treg P =.14; BM vs. WT Treg P =.19; BM vs. IL-17 KO Treg P =.12. For the 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratio: BM vs. Tcon P =.05; WT Treg vs. IL-17 KO Treg P =.8; Tcon vs. WT Treg P =.72; Tcon vs. IL-17 KO Treg P = .54; BM vs. WT Treg P = .08; BM vs. IL-17 KO Treg P = .09.

Selective IL-1 Signaling Blockade Does Not Enhance Treg-Mediated GVHD Suppressive Ability In Vivo

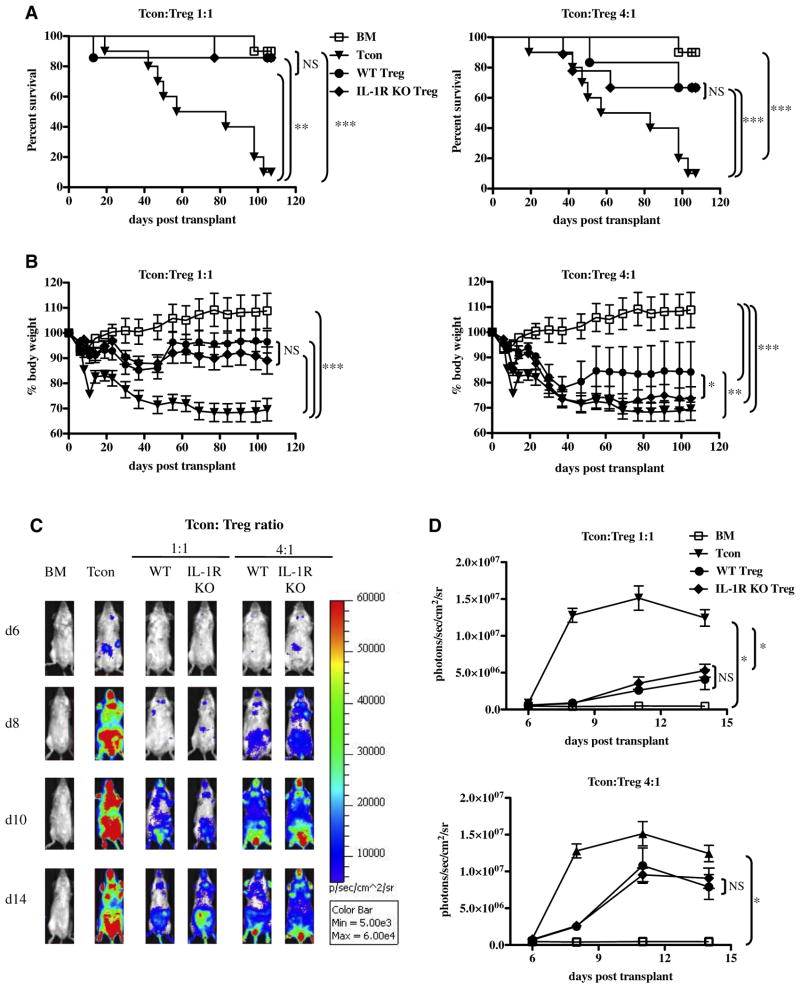

IL-17A production is not the sole mechanism by which Th17 cells exert their proinflammatory activity. For example, Th17 cells also produce large amounts of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-17F, IL-22, and IL-21 [40,41]. Thus, we sought to confirm the results obtained with the IL-17A KO Treg by comparing WT Treg with Treg lacking the Il1r1 gene, which were shown to be resistant to Th17 conversion in vivo and in vitro [29,30]. Specifically, IL-1β signaling was shown to be necessary for the differentiation of both human [42] and mouse Th17 cells [29] as well as for the conversion of Treg to Th17 cells in multiple murine models for autoimmune diseases [24,29,30]. We compared the immunosuppressive ability of Treg isolated from IL-1R1 KO mice, unable to respond to either IL-1α or IL-1β signals [43], to that of WT Treg. We reasoned that by interrupting IL-1 signaling selectively in Treg, we would completely prevent Treg to Th17 conversion, possibly stabilizing Treg immunosuppressive phenotype and enhancing GVHD suppression. Nevertheless, similar to the results obtained with the IL-17 KO Treg in vivo, the GVHD inhibitory capacity of Treg isolated from IL-1R KO mice was equivalent to that of WT Treg (Figure 3). No difference was noted when comparing the survival (Figure 3A) and BLI signals (Figure 3C) of mice recipients of high doses of either WT or IL-1R KO Treg. The recovery of weight of mice recipients of WT Treg revealed only a minor improvement compared with that of mice recipients of IL-1R KO Treg at the lower Treg doses (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

IL-1R signaling blockade does not affect the GVHD suppressive capacity of Treg in vivo. (A) Survival curves of recipient mice transplanted with BM alone (BM), BM on day 0 + Tcon on day 2 (Tcon group), and BM cotransplanted with either WT or IL-1R KO Treg, followed by Tcon transplantation 2 days later (Treg group). Both 1:1 and 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratios are shown. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (BM n = 10; Tcon n = 10; WT Tcon/Treg 1:1 n = 7; IL-1R KO Tcon/ Treg 1:1 n = 7; WT Tcon/Treg 4:1 n = 6; IL-1R KO Tcon/Treg 4:1 n = 9). Statistical differences between curves were calculated by the log rank test. For the 1:1 Tcon/ Treg ratio: BM vs. Tcon P =.0002; Tcon vs. WT Treg P =.008; Tcon vs. IL-1R KO Treg P =.004; WT Treg vs. IL-17KO Treg P =.96. For the 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratio: BM vs. Tcon P =.0002; Tcon vs. WT Treg P =.03; Tcon vs. IL-1R KO Treg P =.04; WT Treg vs. IL-17KO Treg P =.88. (B) Weight curves of the same animals as in (A). For consistency, the last weight measurement of each diseased animal was kept in the analysis until the last mouse in the group expired Statistical differences between curves were calculated with a 2-tailed Student t-test. For the 1:1 Tcon/Treg ratio: BM vs. Tcon P <.0001.; Tcon vs. WT Treg P <.0001; Tcon vs. IL-1R KO Treg P <.0001; WT Treg vs. IL-1R KO Treg P =.43; BM vs. WT Treg P <.0001; BM vs. IL-1R KO Treg P <.0001. For the 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratio: BM vs. Tcon P <.0001; Tcon vs. WT Treg P =.001; Tcon vs. IL-1R KO Treg P = .19; WT Treg vs. IL-1R KO Treg P = .04; BM vs. WT Treg P < .0001; BM vs. IL-1R KO Treg P < .0001. (C) In vivo BLI images of representative animals during acute GVHD in the presence or absence of WT and IL-1R KO Treg. Both 1:1 and 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratios are shown. (D) Quantification of the in vivo BLI data derived from luc+ Tcon as a measure of ongoing GVHD. Both Tcon/Treg ratios of 1:1 and 4:1 are shown. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments (BM n = 10; Tcon n = 10; WT Tcon/Treg 1:1 n = 7; IL-1R KO Tcon/Treg 1:1 n = 7; WT Tcon/Treg 4:1 n = 6; IL-1R KO Tcon/Treg 4:1 n = 9). Probability values were calculated with a 2-tailed unpaired Student t-test. For the 1:1 Tcon/Treg ratio: BM vs. Tcon P =.02; Tcon vs. WT Treg P =.05; Tcon vs. IL-1R KO Treg P =.06; WT Treg vs. IL-1R KO Treg P =.72; BM vs. WT Treg P =.1; BM vs. IL-1R KO Treg P =.11. For the 4:1 Tcon/Treg ratio: BM vs. Tcon P =.02; Tcon vs. WT Treg P =.27; Tcon vs. IL-1R KO Treg P =.26; WT Treg vs. IL-1R KO Treg P = .99; BM vs. WT Treg P = .08; BM vs. IL-1R KO Treg P = .07.

Only a Minority of Highly Purified Treg Converts into IL-17–Producing Cells In Vivo

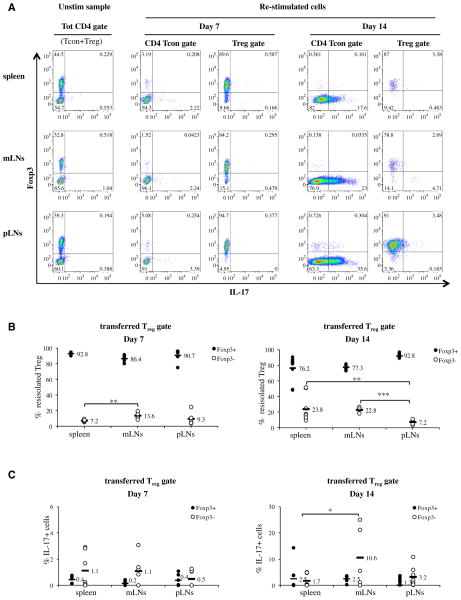

We then monitored whether we could detect the conversion of Treg into IL-17–producing cells upon ex vivo reisolation of the transferred Treg and intracellular cytokine staining. Similar to the above-described experiments, we first transferred highly purified WT Treg into the BM-transplanted recipients, and then induced GVHD by cotransferring purified Tcon 2 days later. We monitored Treg to Th17 conversion in the spleen and lymph nodes of the transplanted animals by intracellular cytokine staining, with the aid of congenic markers 7 and 14 days later. Specifically, the transferred Treg were identified as CD4+CD45.1−Thy1.2+H-2b+cells to distinguish them from the CD45.1−Thy1.1+H-2b+ BM-derived cells, the CD45.1+Thy1.1+H-2b+ Tcon, and the CD45.1−Thy1.1−H-2d+ residual recipient-derived hematopoietic cells. A significant proportion of CD4+ Tcon produced detectable IL-17 approximately 2 weeks after GVHD induction (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 4.

WT Treg do not produce IL-17 after GVHD induction in vivo. (A) TCD-BM cells and Treg were cotransplanted on day 0 after lethal irradiation, followed by Tcon 2 days later (d +2). The animals were sacrificed 7 and 14 days after BM transplantation (5 and 12 days post-GVHD induction), and lymphoid organs were subjected to intracellular IL-17 and Foxp3 staining for FACS analysis. Treg were gated as live CD4+CD45.1−Thy1.2+H-2b+, whereas Tcon were identified as CD4+CD45.1+Thy1.1+H-2b+. Donor BM cells and residual recipient hematopoietic cells (H-2d+) were gated out as CD45.1−Thy.1.1+H-2b+ and CD45.1−Thy1.1−H-2d+ cells, respectively. (B) Quantification of the intracellular Foxp3 staining data presented in (A). Live CD4+CD45.1−Thy1.2+H-2b+ Treg were reisolated 7 and 14 days after in vivo transfer and reanalyzed for intracellular Foxp3 expression. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. Day 7: n = 7 in all groups. Day 14: spleen n = 7; mLN = mesenteric lymph nodes: n = 5; pLN = peripheral lymph nodes: n = 9. Statistical differences between groups were calculated with a 2-tail unpaired Student t-test. Day 7: spleen vs. mLNs P = .002; mLNs vs. pLNs P = NS; spleen vs. pLNs P = NS. Day 14: spleen vs. mLNs P = NS; mLNs vs. pLNs P < .0001; spleen vs. pLNs P =.008. (C) Quantification of the Treg intracellular IL-17 staining data presented in (A). CD4+CD45.1−Thy1.2+H-2b+ transferred Treg were re -isolated 7 and 14 days after in vivo transfer and analyzed for intracellular IL-17 production. IL-17 production by both Foxp3+ and Foxp3− reisolated Treg is shown. Statistical differences between groups were calculated with a 2-tail unpaired Student t-test. Day 7: spleen vs. mLNs P = NS; mLNs vs. pLNs P = NS; spleen vs. pLNs P = NS. Day 14: spleen vs. mLNs P = .04; mLNs vs. pLNs P = .1; spleen vs. pLNs P = NS.

Conversely, consistent with our in vivo GVHD suppression experiments, we could detect little or no IL-17 production upon ex vivo reisolation of the transferred Treg (Figure 4). Interestingly, approximately 10% to 20% of the transferred Tregs did lose Foxp3 expression during ongoing GVHD (Figure 4B). Not surprisingly, we detected a small increase in IL-17–producing cells among the Treg that lost Foxp3 expression (Figure 4C). However, the proportion of IL-17–producing cells was low in both Foxp3+ and Foxp3low/neg subsets of the reisolated Treg (Figure 4C). Thus, freshly isolated and highly purified Treg do not appear to convert into IL-17–producing cells in our model, suggesting that IL-17 production is not a factor affecting Treg stability during ongoing GVHD.

DISCUSSION

We previously demonstrated that Treg-based immunotherapy is a promising strategy for the prevention of GVHD after bone marrow transplantation [9,15–18]. However, the stability of Treg have been questioned in different experimental models, with multiple studies describing the conversion of Treg into IL-17–producing cells under the influence of inflammatory stimuli [21–30]. Novel evidence has uncovered a common developmental pathway shared by Treg and Th17 cells. Both cells types are dependent on transforming growth factor-β for their development from naive T cells [44,45]. Furthermore, transcription factor interplay has been demonstrated in Tregs and Th17 cells in different in vivo and in vitro experimental models [24,46–48], revealing developmental plasticity between the two T cell subsets. In particular, antigen-activated naive T cells coexpress Foxp3 and RoRγτ upon exposure to transforming growth factor-β [47], which represent the main transcription factors driving the differentiation of Treg and Th17 cells, respectively.

Moreover, Foxp3 was shown to directly bind and inhibit the Th17-driving transcription factors RoRγτ and RoRα, whereas Foxp3 itself is inhibited in a STAT3-dependent manner once Th17 differentiation ensues [24,46,47,49]. However, although mature Treg were shown to convert into IL-17–producing cells under different inflammatory conditions [21–30], to our knowledge, terminally differentiated Th17 cells have never been demonstrated to convert into Foxp3+ Treg in vivo. This suggests that Treg to Th17 conversion might be a unidirectional phenomenon that could impact the suppressive ability of Treg in vivo. Although such Treg plasticity is likely to be beneficial upon infection with extracellular pathogens and fungi, the one-way conversion of Treg into IL-17–producing cells could affect the stability of Treg suppressive phenotype and function during Treg immunotherapy in vivo. Thus, developing strategies to block such conversion might enhance the biological activity of Treg in vivo.

A better understanding of Treg biology is pivotal for the optimization of our preclinical protocols aimed to enhance Treg-mediated GVHD suppressive ability in vivo. This prompted us to evaluate whether Il17a gene ablation would result in the stabilization of Treg suppressive phenotype in vitro and in vivo. Our laboratory recently adapted our preclinical model to ongoing clinical trials (Negrin, unpublished results), and we and others [19,20] are currently assessing the efficacy of highly purified human Treg in a clinical setting. Our ultimate goal is to translate the insights obtained in our preclinical studies into novel therapeutic strategies, with the idea of minimizing the risk of GVHD and the use of immunosuppressive drugs after HCT, which predispose transplanted patients to an increased risk of opportunistic infections. Indeed, when cotransferred into lethally irradiated mice recipient of TCD-BM and Tcon, Treg resulted in enhanced immune reconstitution and increased survival after challenge with viral pathogens [16], without interfering with Tcon-mediated tumor clearance due to a reduction in GVHD mediated damage to lymphoid tissues.

When we assayed the immunomodulatory capacity of Treg in an MLR in vitro, IL-17 KO Treg demonstrated an approximate 2-fold increase in their ability to control the proliferation of allospecific Tcon in vitro (Figure 1). However, such enhancement did not impact the in vivo activity of IL-17 KO Treg, which had comparable biological activity to WT Treg in suppressing GVHD (Figure 2). Similarly, selective blockade of IL-1 signaling in Treg, which has been shown to be necessary for Th17 conversion [29,30], did not enhance the ability of Treg to control GVHD progression in vivo (Figure 3). Furthermore, when we monitored whether WT Treg do in fact convert into IL-17–producing cells in vivo, we could detect little or no IL-17 production by WT Treg upon GVHD induction (Figure 4). It remains possible that IL-17–deficient Treg may lead to different results and, possibly, show an improvement of Treg function in a different bone marrow transplantation model, such as a minor mismatched model. Of note, we subjected our recipients to total body irradiation and H-2-mismatched Tcon and BM transplantation, which is characterized by high proinflammatory cytokine production, named the “cytokine storm,” with high levels of IL-6 and IL-1 [50,51], 2 of the major cytokines driving Treg to Th17 conversion. Thus, we reasoned that if we could not detect any Th17 conversion after total body irradiation regimen in a major MHC-mismatched model, it was unlikely for us to obtain more promising results upon Treg-specific IL-17 gene ablation in a minor mismatch model.

Natural Treg represent a heterogeneous population, a portion of which has been consistently shown to be unstable and to lose Foxp3 expression under inflammatory conditions, from where the name “ex Treg” [52]. In line with these observations, approximately 10% to 20% of the transferred Tregs lost Foxp3 expression during acute GVHD (Figure 4B). Becasue we did not note any functional differences between IL-17 deficient and IL-17 sufficient Treg, we did not attempt to quantify in detail the numbers of IL-17 sufficient versus IL-17 KO ex Treg after GVHD induction. Thus, the phenotypic stability and Foxp3 expression profiles of IL-17–deficient Treg remain yet to be characterized. Because of the low number of cells obtained upon ex vivo reisolation, we could not assess whether such Treg losing Foxp3 expression have impaired ability to suppress T cell proliferation in vitro or GVHD in vivo. However, our in vitro studies indicate that Foxp3 down-regulation is indeed associated with a loss of Treg suppressive ability in vivo. Further, prior studies using the immunosuppressive drug cyclosporine A resulted in a reduction of Treg in vivo function, associated with a reduction in Foxp3 expression that could be overcome by exogenous IL-2 [53].

Our results argue that despite a mild increase in their ability to control the proliferation of allogeneic Tcon in vitro, IL-17 targeting does not improve Treg-mediated control of GVHD responses in vivo. We believe the slight improvement in the Treg function seen in vitro is not sufficient to be translated to the in vivo setting, as GVHD develops after sustained activation of a much more complex set of cytokine cascades and of different cellular subsets than those activated in a short-term in vitro assay. Indeed, our in vivo model involves GVHD induction across major histocompatibility barriers, where a cytokine storm [51] likely interferes with the mildly enhanced suppressive ability of IL-17 KO Treg, the result appearing to be comparable with that seen with WT Treg. The mild improvement in the Tcon suppressive ability by IL-17 KO Treg shown in vitro may be a consequence of the complete lack of IL-17 exposure in the donor mice. However, to our knowledge, there is no report describing an increase in the suppressive function of Treg isolated from IL-17 KO mice. Our study did not address the impact of Treg-specific IL-17 gene inactivation on Tcon to Treg conversion. It has been suggested that human IL-17–producting Treg may be instrumental in controlling Th17-mediated inflammation by responding to the same inflammatory chemoattractants, allowing specific suppression of Th17 cell activation at the site of inflammation [54]. Thus, the study on Tcon to Treg conversion in presence or absence of Treg-produced IL-17 is in need of further investigation.

Overall, our results argue that most highly purified Treg do not convert into IL-17–producing cells during an ongoing alloreaction in vivo, suggesting that IL-17 and/or IL-1β targeting are not likely to be productive strategies to improve Treg immunotherapy after allogeneic HCT. We performed our experiments with freshly isolated CD4+CD25bright natural Treg and therefore cannot exclude that IL-17 deficiency may lead to a functional advantage upon in vitro expansion. Because Treg abundance is a major issue for Treg immunotherapy in human patients, the functional assessment of IL-17 KO Treg after in vitro expansion is worthy of further investigation.

Further studies are needed to attempt to stabilize the Treg suppressive phenotype and prevent Foxp3 loss after the transfer of purified Treg and GVHD induction in vivo. In an effort to optimize Treg immunotherapy after HCT, we are currently assessing the efficacy of Treg that lack specific inhibitory molecules and of Tregs that have been expanded and activated in vitro or in vivo with the use of particular immunosuppressive medications or cytokines. Importantly, if successful, Treg immunotherapy may be extended to further clinical applications, such as tolerance induction in the context of severe autoimmune diseases and/or solid organ transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.07.024.

Financial Disclosure: Supported by the Stanford University training grant in “Molecular and Cellular Immunobiology” 5 T32 AI07290, P01s CA49605, and HL075462.

References

- 1.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wing K, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells exert checks and balances on self tolerance and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:7–13. doi: 10.1038/ni.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tarbell KV, Yamazaki S, Olson K, et al. CD25+ CD4+ T cells, expanded with dendritic cells presenting a single autoantigenic peptide, suppress autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1467–1477. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scalapino KJ, Tang Q, Bluestone JA, et al. Suppression of disease in New Zealand Black/New Zealand White lupus-prone mice by adoptive transfer of ex vivo expanded regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:1451–1459. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang Q, Bluestone JA, Kang SM. CD4(+)Foxp3(+) regulatory T cell therapy in transplantation. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4:11–21. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golshayan D, Jiang S, Tsang J, et al. In vitro-expanded donor alloantigen-specific CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells promote experimental transplantation tolerance. Blood. 2007;109:827–835. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joffre O, Santolaria T, Calise D, et al. Prevention of acute and chronic allograft rejection with CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T lymphocytes. Nat Med. 2008;14:88–92. doi: 10.1038/nm1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood KJ, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in transplantation tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:199–210. doi: 10.1038/nri1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann P, Ermann J, Edinger M, et al. Donor-type CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells suppress lethal acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Exp Med. 2002;196:389–399. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor PA, Lees CJ, Blazar BR. The infusion of ex vivo activated and expanded CD4(+)CD25(+) immune regulatory cells inhibits graft-versus-host disease lethality. Blood. 2002;99:3493–3499. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen JL, Trenado A, Vasey D, et al. CD4(+)CD25(+) immunoregulatory T Cells: new therapeutics for graft-versus-host disease. J Exp Med. 2002;196:401–406. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trenado A, Charlotte F, Fisson S, et al. Recipient-type specific CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells favor immune reconstitution and control graft-versus-host disease while maintaining graft-versus-leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1688–1696. doi: 10.1172/JCI17702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trenado A, Sudres M, Tang Q, et al. Ex vivo-expanded CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells prevent graft-versus-host-disease by inhibiting activation/differentiation of pathogenic T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:1266–1273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones SC, Murphy GF, Korngold R. Post-hematopoietic cell transplantation control of graft-versus-host disease by donor CD425 T cells to allow an effective graft-versus-leukemia response. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003;9:243–256. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2003.50027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edinger M, Hoffmann P, Ermann J, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells preserve graft-versus-tumor activity while inhibiting graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Nat Med. 2003;9:1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen VH, Shashidhar S, Chang DS, et al. The impact of regulatory T cells on T-cell immunity following hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2008;111:945–953. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-103895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen VH, Zeiser R, Dasilva DL, et al. In vivo dynamics of regulatory T-cell trafficking and survival predict effective strategies to control graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic transplantation. Blood. 2007;109:2649–2656. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-044529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen VH, Zeiser R, Negrin RS. Role of naturally arising regulatory T cells in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:995–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Ianni M, Falzetti F, Carotti A, et al. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:3921–3928. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunstein CG, Miller JS, Cao Q, et al. Infusion of ex vivo expanded T regulatory cells in adults transplanted with umbilical cord blood: safety profile and detection kinetics. Blood. 2011;117:1061–1070. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-293795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi T, Chen Y, Wang L, et al. Reciprocal differentiation and tissue-specific pathogenesis of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells in graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;114:3101–3112. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu L, Kitani A, Fuss I, Strober W. Cutting edge: regulatory T cells induce CD4+CD25-Foxp3− T cells or are self-induced to become Th17 cells in the absence of exogenous TGF-beta. J Immunol. 2007;178:6725–6729. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Afzali B, Mitchell P, Lechler RI, et al. Translational mini-review series on Th17 cells: induction of interleukin-17 production by regulatory T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;159:120–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang XO, Nurieva R, Martinez GJ, et al. Molecular antagonism and plasticity of regulatory and inflammatory T cell programs. Immunity. 2008;29:44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osorio F, Leibund GutLandmann S, Lochner M, et al. DC activated via dectin-1 convert Treg into IL-17 producers. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:3274–3281. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radhakrishnan S, Cabrera R, Schenk EL, et al. Reprogrammed FoxP3+ T regulatory cells become IL-17+ antigen-specific autoimmune effectors in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:3137–3147. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27.Deknuydt F, Bioley G, Valmori D, Ayyoub M. IL-1beta and IL-2 convert human Treg into T(H)17 cells. Clin Immunol. 2009;131:298–307. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang JH, Xiao Y, Hu H, et al. Ubc13 maintains the suppressive function of regulatory T cells and prevents their conversion into effector-like T cells. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:481–490. doi: 10.1038/ni.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung Y, Chang SH, Martinez GJ, et al. Critical regulation of early Th17 cell differentiation by interleukin-1 signaling. Immunity. 2009;30:576–587. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Kim J, Boussiotis VA. IL-1beta-mediated signals preferentially drive conversion of regulatory T cells but not conventional T cells into IL-17-producing cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:4148–4153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tartar DM, VanMorlan AM, Wan X, et al. FoxP3+RORgammat+ T helper intermediates display suppressive function against autoimmune diabetes. J Immunol. 2010;184:3377–3385. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakae S, Komiyama Y, Nambu A, et al. Antigen-specific T cell sensitization is impaired in IL-17-deficient mice, causing suppression of allergic cellular and humoral responses. Immunity. 2002;17:375–387. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kappel LW, Goldberg GL, King CG, et al. IL-17 contributes to CD4-mediated graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113:945–952. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-172155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yi T, Zhao D, Lin CL, et al. Absence of donor Th17 leads to augmented Th1 differentiation and exacerbated acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2008;112:2101–2110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-126987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nyirenda MH, Sanvito L, Darlington PJ, et al. TLR2 stimulation drives human naive and effector regulatory T cells into a Th17-like phenotype with reduced suppressive function. J Immunol. 2011;187:2278–2290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beriou G, Costantino CM, Ashley CW, et al. IL-17-producing human peripheral regulatory T cells retain suppressive function. Blood. 2009;113:4240–4249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beilhack A, Schulz S, Baker J, et al. In vivo analyses of early events in acute graft-versus-host disease reveal sequential infiltration of T-cell subsets. Blood. 2005;106:1113–1122. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao YA, Wagers AJ, Beilhack A, et al. Shifting foci of hematopoiesis during reconstitution from single stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:221–226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2637010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Negrin RS, Contag CH. In vivo imaging using bioluminescence: a tool for probing graft-versus-host disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:484–490. doi: 10.1038/nri1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, et al. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park H, Li Z, Yang XO, et al. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Napolitani G, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Interleukins 1beta and 6 but not transforming growth factor-beta are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing human T helper cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:942–949. doi: 10.1038/ni1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glaccum MB, Stocking KL, Charrier K, et al. Phenotypic and functional characterization of mice that lack the type I receptor for IL-1. J Immunol. 1997;159:3364–3371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O’Quinn DB, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Du J, Huang C, Zhou B, Ziegler SF. Isoform-specific inhibition of ROR alpha-mediated transcriptional activation by human FOXP3. J Immunol. 2008;180:4785–4792. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou L, Lopes JE, Chong MM, et al. TGF-beta-induced Foxp3 inhibits T(H)17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORgammat function. Nature. 2008;453:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature06878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang F, Meng G, Strober W. Interactions among the transcription factors Runx1, RORgammat and Foxp3 regulate the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1297–1306. doi: 10.1038/ni.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ichiyama K, Yoshida H, Wakabayashi Y, et al. Foxp3 inhibits RORgammat-mediated IL-17A mRNA transcription through direct interaction with RORgammat. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17003–17008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801286200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xun CQ, Thompson JS, Jennings CD, et al. Effect of total body irradiation, busulfan-cyclophosphamide, or cyclophosphamide conditioning on inflammatory cytokine release and development of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease in H-2-incompatible transplanted SCID mice. Blood. 1994;83:2360–2367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferrara JL, Levine JE, Reddy P, Holler E. Graft-versus-host disease. Lancet. 2009;373:1550–1561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60237-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout SL, Jeker LT, et al. Instability of the transcription factor Foxp3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1000–1007. doi: 10.1038/ni.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeiser R, Nguyen VH, Beilhack A, et al. Inhibition of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell function by calcineurin-dependent interleukin-2 production. Blood. 2006;108:390–399. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Voo KS, Wang YH, Santori FR, et al. Identification of IL-17-producing FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4793–4798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900408106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.