Abstract

Mutations in the lamin A/C gene are involved in multiple human disorders for which the pathophysiological mechanisms are partially understood. Conflicting results prevail regarding the organization of lamin A and C mutants within the nuclear envelope (NE) and on the interactions of each lamin to its counterpart. We over-expressed various lamin A and C mutants both independently and together in COS7 cells. When expressed alone, lamin A with cardiac/muscular disorder mutations forms abnormal aggregates inside the NE and not inside the nucleoplasm. Conversely, the equivalent lamin C organizes as intranucleoplasmic aggregates that never connect to the NE as opposed to wild type lamin C. Interestingly, the lamin C molecules present within these aggregates exhibit an abnormal increased mobility. When co-expressed, the complex formed by lamin A/C aggregates in the NE. Lamin A and C mutants for lipodystrophy behave similarly to the wild type. These findings reveal that lamins A and C may be differentially affected depending on the mutation. This results in multiple possible physiological consequences which likely contribute in the phenotypic variability of laminopathies. The inability of lamin C mutants to join the nuclear rim in the absence of lamin A is a potential pathophysiological mechanism for laminopathies.

Keywords: Lamin A/C gene, Laminopathy, Nuclear envelope, FRAP, Electron microscopy

Introduction

The lamin A/C gene (LMNA) has been implicated in numerous diseases referred to as “laminopathies” that affect the heart, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, bones, peripheral nerves, skin, or cause premature aging [1].

Lamins A and C are type V intermediate filament proteins expressed in terminally differentiated somatic cells, and synthesized by alternative splicing of LMNA. Both proteins share the same first 566 amino acids but differ in their carboxyl terminus. Lamins A and C have 646 and 572 amino acids respectively and are known for their structural role in supporting the nuclear architecture and anchoring chromatin and the nuclear pore complexes to the nuclear membrane. Indeed, along with B-type lamins, they are the main components of the lamina, a filamentous meshwork underlying the inner nuclear membrane. However, they are also present within the nucleus [2]. In addition to participating in nuclear architecture, there is a growing body of evidence showing that lamin A/C plays a key role in gene transcription regulation, DNA repair and replication [1,3], and cell differentiation regulation [1,4,5]. The list of lamins A and C partners is regularly growing [2,6–9], which confirms that these proteins are involved in multiple functions, some of which are still being unravelled. For instance, it has recently been shown that lamins A and C are tightly connected to the cytoskeleton, thus revealing a nuclear–cytoskeletal continuity [10]. Also, some LMNA mutations have been reported to affect the posttranslational machinery of the cell. It has been shown that the nuclear localization of SUMO1 (ubiquitin-related modifier1) is totally disrupted in the presence of the DCM-associated D192G lamin C mutant [11].

Whether or not lamin A is required for lamin C to be localized into the nuclear envelope remains debated. The early death of lmna knockout mice (lmna−/−) [12] or the dramatic lamina defects observed when silencing lamin A/C in human endometrial stromal cells [13], clearly demonstrates that at least one of the two proteins is required for survival. However, a recent study in fibroblasts from mice expressing only lamin C have shown that lamin C is normally targeted to the nuclear envelope [14]. As well, nuclei shape from these fibroblasts is only mildly altered and the mice do not exhibit any symptoms of muscle diseases. Furthermore, lamin C has also been shown to be sufficient for proper localization of both emerin [14] and nesprin-2 [15] at the nuclear envelope. These studies therefore suggest that lamin C can substitute for lamin A on its own and provide functional support to the nuclear envelope. However, these results strikingly contradict several other studies which showed that lamin A targets both lamin C and emerin to the nuclear envelope [16–19].

Furthermore, nuclear envelope alterations associated with LMNA mutations have long been reported [11,20–23]. Mice expressing M371K lamin A exhibit cardiomyocytes with convoluted nuclear envelopes, intranuclear inclusions and chromatin clumps in nuclei [24]. Several LMNA mutations are known to result in the aggregation of lamin A in vitro [18,25–27]. In a previous report, we found DCM-causingLMNA mutations leading to the aggregation of nuclear lamin C as well [11]. However, the physiological consequences of these aggregates as well as the impact of these mutations on lamin C specifically or on the complex lamin A/lamin C have only been partially investigated. It is unclear whether or not these lamin A and lamin C aggregates retain the capability to incorporate themselves into the nuclear envelope either in combination or independently.

In humans, most reported LMNA mutations are found in Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) but the spectrum of phenotypes is constantly extending [28]. Nuclear fragility and/or abnormalities in the tissue/cell-specific gene expression are the main two hypotheses proposed to explain how mutations in this gene cause such a large spectrum of diseases [1]. However, the exact pathophysiological mechanisms remain puzzling. In this study, we propose to further examine wild type and mutated lamin A and C behaviour separately and then in combination. In an attempt to better clarify the lamin A and lamin C respective functions and shed light on the properties of lamin A/C affected in laminopathies, we compared various LMNA mutations previously reported in DCM (L85R, D192G, N195K) [29], autosomal dominant Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (R386K) [30] or lipodystrophy (R482W) [31].

Methods

Expression plasmid and mutagenesis

Our cloning procedures of wild type and mutated full-length human lamins A and C as C-terminal fusions to either the enhanced cyan, yellow or red fluorescent protein sequence of, respectively pECFP-C1, pEYFP-C1, and pDsRed2-C1 fluorescent expression vectors, have previously been described [11]. L85R, D192G, N195K, R386K and R482W point mutations were introduced in the lamin A and lamin C cDNAs by site directed mutagenesis using primers previously published [11,18,27]. All clones were systematically sequenced.

Fluorescent microscopy

Images were captured on an Olympus 1×70 inverted microscope and processed using TILLvisION software (version 4.0), or an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 confocal microscope with a 100× 1.4 NA oil immersion objective (UplanSApo) and using the Olympus FV-10 acquisition software, version 5.0, to acquire images.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching experiments (FRAP)

FRAP experiments were performed on living transfected COS7 cells at 37 °C. Only the transfected cells displaying a phenotype characteristic of the mutation investigated were considered for FRAP experiments. To minimize cell physiology disturbance, we chose to photobleach selected areas for 10 iterations at 16% power of the argon laser. After photobleaching, 42 images were captured every 5 s for 210 s at 1.5% power of the argon laser. FRAP was performed during such a short period of time to limit bias due to nuclear rotation and cell movement. Average fluorescence intensity in each region of interest was normalized to total cellular fluorescence loss during bleach and imaging phase as Irel = T0It/TtI0 as described by Phair et al. [32] (T0, total cellular intensity during prebleach; Tt, total cellular intensity at time t; I0, average intensity in the region of interest during prebleach, It, average intensity in the region of interest at time t). Fluorescence of surrounding cells was taken into account in cases of cells exhibiting a single speckle (mutation D192G and R386K). A non linear regression was used to create a best fit curve. Difference in the t1/2 between L85R, D192G, R386K and wild type lamin C aggregates was assessed by a T-test.

Immunocytochemistry

Transfected cells were fixed on coverslips with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and permeabilized with 10% Triton-100 for 5 min. Cells were incubated with the primary antibody (RanGap1 (N-19) polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz)) in 10% fetal bovine serum (1:50) and with Alexa Fluor 594-labeled Rabbit Anti-Goat antibody (Molecular Probes) for 30 min. The coverslips were mounted on a glass slide with mowiol.

Immunoblotting

Western blot analyses were performed as previously described by Sylvius et al. [11]. The primary antibody used was goat anti-lamin A/C (N-18) polyclonal antibody and mouse anti beta actin (C4) monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz) and the secondary antibodies were peroxidase-linked anti-goat and anti-rabbit antibodies (Santa Cruz).

Cell preparation for EM

Cells were fixed in 1.6% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.2. They were then resuspended in 15% bovine serum albumin infiltrated for 30 min and pelleted by centrifugation. The supernatant was removed and the cellpellets were coagulated with 1.6% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.2. The resulting firm pellets were cut into 1 mm pieces post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide dehydrated in ascending alcohols and embedded in Spurr epoxy resin. Thin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a Jeol 1230 TEM equipped with AMT software.

Results

We transiently expressed the full-length human wild type and the various mutant lamins A and C cDNAs fused to the C-terminus of variants of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein (GFP) (lamin-FP) in fibroblast COS7 and rat cardiomyoblast H9C2 cells. To assess the consequences of mutations on lamin A and C properties specifically, we used confocal immunofluorescence microscopy to examine the cells expressing lamins A-FP and C-FP separately and then together.

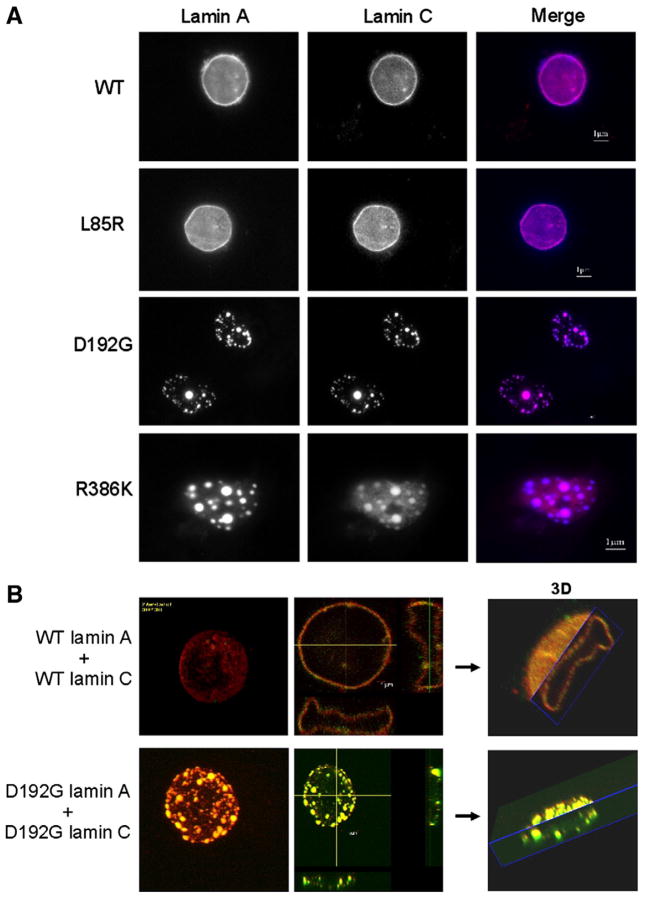

Lamin A mutants aggregate

The wild type phenotype was characterized by a homogeneous distribution of the protein throughout the nucleus (Fig. 1A). L85R and R482W lamin A-FP did not exhibit any aberrant phenotype compared to the wild type (Figs. 1A and B). It is noted that the images of cells expressing L85R lamin A were carefully analyzed since this mutant was previously reported as slightly different from the wild type [18]. In contrast, D192G, N195K and R386K lamin A-FP accumulated in abnormal, giant aggregates (Figs. 1A and B), which is consistent with results already described in C2C12 or COS7 cells [11,26,27]. Several immunofluorescence microscopy studies performed on cells lines transfected with lamin A/C have reported the aggregation of lamin A as intra-nuclear foci or nuclear aggregates inside the nucleoplasm [18,25–27]. To confirm this statement in our analyses, we used confocal immunofluorescence microscopy and 3D reconstruction of the cell (Fig. 2). Although we could not exclude the presence of nucleoplasmic aggregates, it was obvious that the aggregates were massively present at the periphery of the nucleus and led to a punctate aspect of the nucleus, as shown on Fig. 2. This punctate aspect suggests that lamin A-FP mutants retain the ability to locate at the nuclear envelope, albeit not properly.

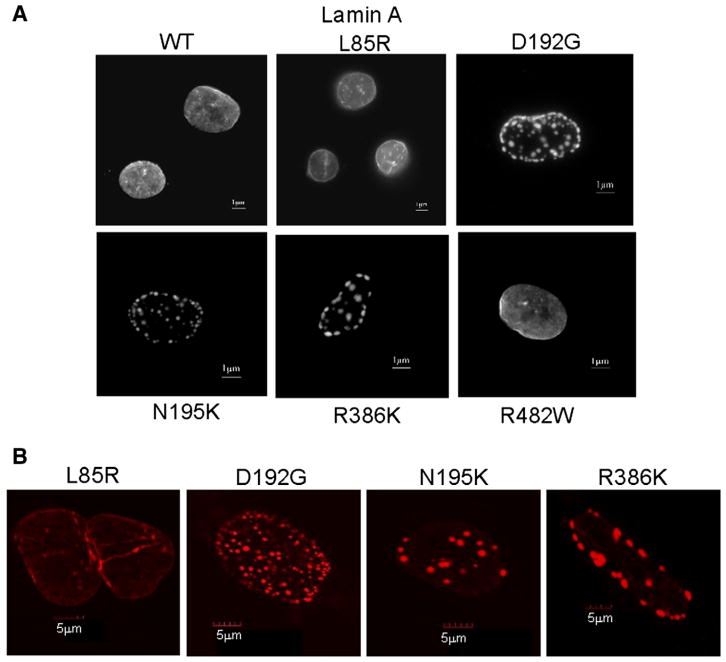

Fig. 1.

A. Nuclei expressing wild type or the various lamin A mutant constructs transiently expressed as ECFP fusion protein in COS7 cells. Cells were visualized by wide-field fluorescence microscopy with an excitation wavelength of 433 nm. Wild type lamin A, as well as L85R and R482W lamin A mutants homogeneously organize throughout the nucleus. In contrast, D192G, N195K and R386K lamin A mutants accumulate in abnormal aggregates. The nuclear membrane appears granular and discontinued. B. The abnormal lamin A aggregation previously found in COS7 cells expressing D192G, N195K and R386K lamin A, was confirmed in nuclei of rat cardiomyoblast H9C2 cells as opposed to cells expressing wild type or L85R lamin A (not shown).

Fig. 2.

Confocal microscopy picture of H9C2 cell nuclei transiently expressing D192G lamin A as ECFP fusion protein. Mutated lamin A organizes as aberrant aggregates. However, the spherical organization of these aggregates reveal that they are likely embedded in the nuclear envelope.

Abnormal lamin C aggregation is a common feature of several LMNA mutations

We then examined the effect of these mutations on lamin C only. As previously described, wild type lamin C-FP gave rise to multiple small intranuclear aggregates, known as speckles, that are evenly distributed throughout the nucleus [11]. R482W lamin C-FP showed a phenotype similar to the wild type whereas D192G lamin C-FP accumulated in one or two intranuclear giant speckles (Fig. 3), which agrees with previously published studies performed on COS7 or HeLa cells [11,18]. Interestingly, L85R, D192G, N195K, and R386K lamin C-FP mutants also showed a dramatic aggregation in the vast majority of transfected cells (Fig. 3). In COS7 cells, the respective mean speckle diameters were 4.7+/−2 μm (n=9) for L85R lamin C-FP, 5.2+/−1 μm (n=11) for D192G lamin C-FP, 5.3+/−2.5 μm (n=3) for N195K lamin C-FP, 7.1+/−4 μm (n=10) for R386K lamin C-FP, and 2.9+/−1.5 μm (n=11) for wild type lamin C-FP. The mean nuclear diameter was 15 μm (+/−1.5 μm) for all transfected COS7 cells. Intriguingly, L85R lamin C-FP exhibited an aberrant phenotype compared to wild type lamin C-FP, as opposed to its counterpart lamin A-FP which behaved similarly to the wild type lamin A-FP. This suggests that both proteins were differentially affected by the mutation. Aberrant aggregation of nuclear lamin C-FP was observed in less than 20% of COS7 cells expressing wild type lamin C-FP. This proportion was similar to that we previously reported [11].

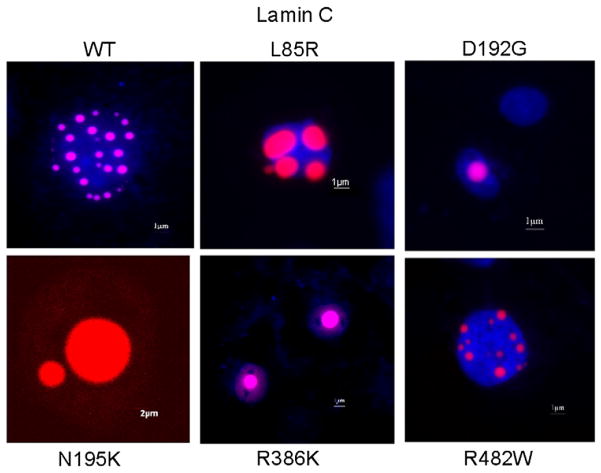

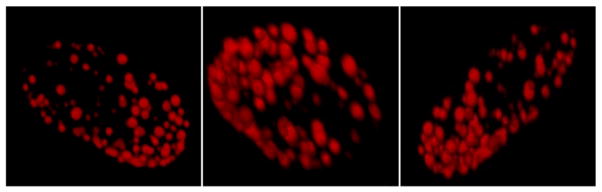

Fig. 3.

Nuclei expressing wild type or the various mutated lamin C constructs transiently expressed as ECFP fusion protein in COS7 cells. Prior to visualization by wide-field fluorescence microscopy, Hoechst 33258 dye was used to locate the nuclei (in blue). Excitation wavelengths were 433 nm for lamin C-ECFP and 365 nm for Hoechst 33258. Note that the aberrant aggregation of the lamin C (in red) within the nucleus visualized by Hoechst 33258 dye is common to several LMNA mutations. Only R482W lamin C mutants responsible for lipodystrophy gave rise to a phenotype similar to the wild type.

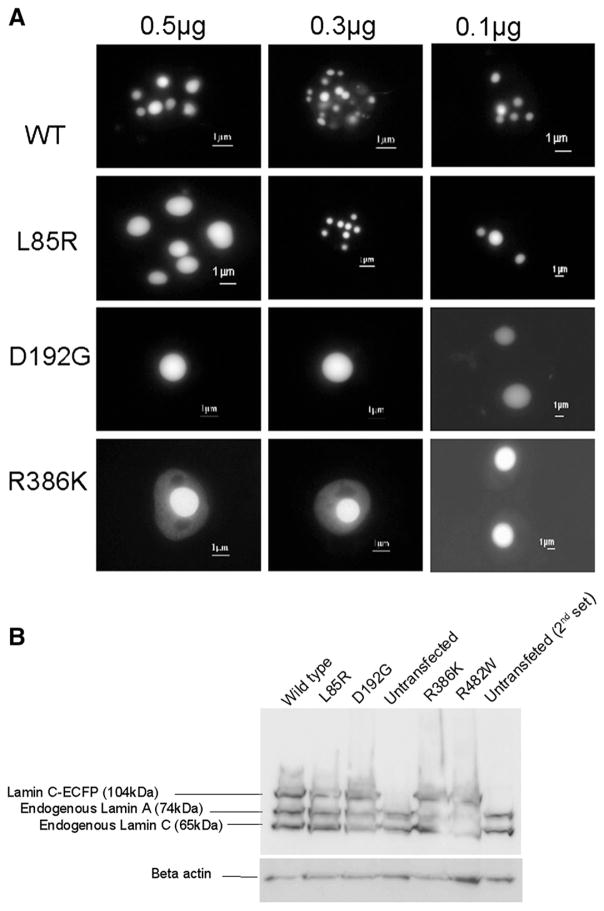

To ensure that this abnormal lamin C aggregation was not an artifact due to the over-expression of the protein we transfected COS7 cells using lower concentrations of constructs (0.3 μg and 0.1 μg). Lamin C-FP mutants formed giant aggregates at each tested concentration indicating that the formation of large aggregates was not an artifact due to an exaggerated dose of DNA (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, Western blotting quantification of lamin mutants did not reveal any difference in the transfection efficiency compared to the wild type, confirming that these giant aggregates did not result from transfection artifact (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

A. Transient transfections of COS7 cells with varying quantity of either wild type or mutated lamin C-FP constructs. Cells were visualized by wide-field fluorescence microscopy with an excitation wavelength of 433 nm. The phenotype observed with mutated lamin C-FP is not due to a too elevated quantity of vectors used to transfect the cells. B. Representative Western blot analysis of COS7 cells transfected with the different lamin C-FP variants and using anti lamin A/C antibody. Results show equal over-expression for all construct.

Mutated lamin C loses its ability to incorporate into the nuclear envelope

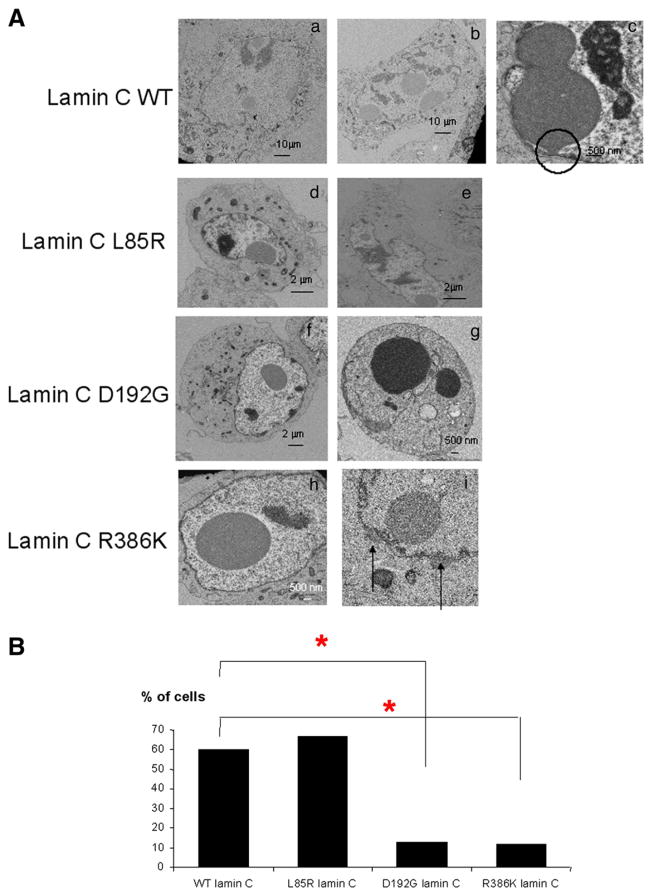

We further assessed whether lamin C aggregates retain their ability to join the nuclear envelope. As a means to better see envelope shape and potential misshapen nuclei, we chose to perform electron microscopy on COS7 cells expressing the wild type or the various lamin C-FP mutants. We restricted the analysis to wild type lamin C and L85R, D192G and R386K lamin C mutants since each of these mutants are representative of a single phenotype. No nuclear deformation was observed in any of the transfected cells. However, in most cells expressing wild type lamin C-FP (60%), lamin C aggregates were in close contact with the nuclear envelope (Fig. 5Aa–b). Clearly, close connections between wild type lamin C aggregates and the nuclear envelope are possible (Fig. 5Ac). Conversely, the number of cells exhibiting such a proximity between aggregates and the nuclear envelope was dramatically reduced in the case of D192G and R386K lamin C-FP (12% and 12.5% respectively; wild type: n=47; D192G: n=38, p<0.01; R386K: n=17, p<0.01) (Figs. 5Af–i and B). In most of these cells, speckles were found within the nucleoplasma and did not exhibit any close connection with the nuclear envelope as opposed to cells expressing wild type lamin C-FP. In the case of L85R lamin C-FP, the percentage of cells exhibiting lamin C aggregates in contact with the nuclear envelope was similar to the wild type (L85R, n=24, p<0.1) (Fig. 5B). This finding implies that wild type lamin C is able to establish connections with the nuclear envelope in the absence of lamin A. This also implies that mutations D192G and R386K caused the inhibition of the lamin C/nuclear envelope connection. The L85R mutation had no effect on this contact. Again, this supports the hypothesis that each LMNA mutation has specific consequences in regards to lamin A/C properties. It is noteworthy to mention that a significant proportion of cells (30%, n=17, p<0.05) expressing R386K lamin C exhibited aggregates abnormally localized outside the nuclear membrane (Arrows in Fig. 5Ai). This is rarely observed in nuclei of cell expressing wild type (<8%, n=47), or the other lamin C mutants (<18% for D192G, n=38, p>0.05; <12% for L85R, n=24, p>0.05). However, electron microscopy analysis of the nuclear envelope of cells expressing R386K lamin C did not reveal any obvious abnormality.

Fig. 5.

A. Electron micrographs of COS7 cells transiently transfected with lamin C-FP constructs. In 60% of cells, wild type lamin C nuclear aggregates were localized in close contact with the nuclear envelope (a–c). Notably, wild type aggregates were able to establish close contact with the nuclear envelope (circle) (c). Similarly, L85R lamin C aggregates organized in contact with the nuclear envelope (d–e). Conversely, in 88% and 87.5% of cells respectively, D192G and R386K lamin C aggregates were found within the nucleoplasm without any contact with the nuclear envelope (f–i). In 30% of cells expressing R386K lamin C, nuclei presented with lamin C aggregates localized outside the nuclear envelope (j–k). B. Percentage of transfected cells displaying lamin C nuclear aggregates in direct contact with the nuclear envelope. χ2 test showed that the number of cells displaying lamin C aggregates in close contact with the nuclear envelope is significantly different in transfected cells expressing D192G or R386K lamin C mutants compared to the wild type (p<0.01).

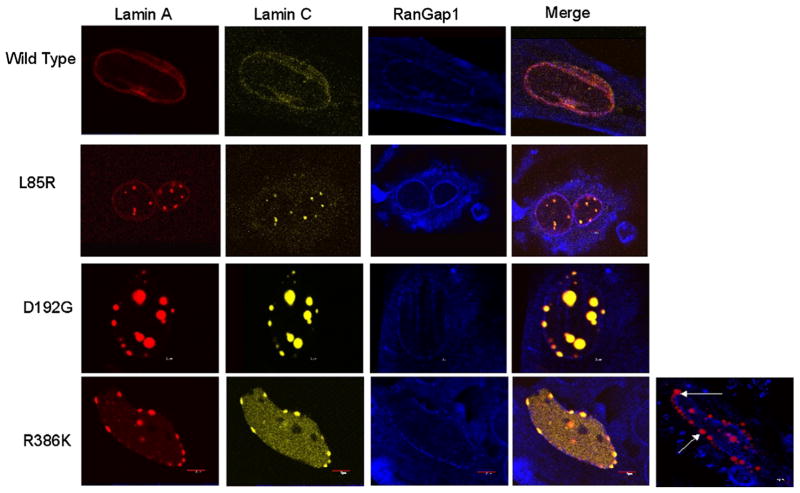

Nuclear localization of lamin A/C mutant complexes in COS7 cells

To find out whether lamin A/C complexes localized in the nuclear envelope, we then co-expressed the wild type and each mutated lamin A-FP with its corresponding lamin C, except for N195K and R482W lamin A/C since these mutants are similar to D192G and wild type respectively. To circumvent bleedthrough issues due to confluent spectral profiles exhibited by C-FP and YFP fluorophores, the wild type and the various lamin A-FP mutants were expressed concomitantly with their counterpart lamin C cloned in pDsRed2-C1 expression vectors. When co-expressed, wild type lamin A-FP and wild type DsRed2-lamin C were homogeneously distributed throughout the nuclear envelope, conferring the nucleus with a veil-like appearance (Fig. 6A). In contrast, D192G and R386K mutants resulted in abnormal aggregations of the complex lamin A/C, which is consistent with previous results [11,18]. Cells expressing L85R lamin A-FP and L85R DsRed2-lamin C exhibited a phenotype similar to the wild type, which suggests that co-expression of both lamins rescues the wild type phenotype. Although L85R DsRed2-lamin C formed speckles within the nucleus (Figs. 3 and 4), we showed that these speckles retained the capacity to make contact with the nuclear envelope (Fig. 5A). Most importantly, even when mutated, lamins A and lamin C always co-localized and were situated in close contact with the nuclear envelope as made evident by confocal microcopy (Fig. 6B). However, in some cells expressing R386K lamins A and C, we observed aberrant localizations of lamin A/C aggregates outside of the nuclear envelope visualized by anti RanGap1 (Arrows in Fig. 7), similarly to cells expressing R386K lamin C-FP only (Fig. 5Ai). Furthermore, the expression of lamin A mutants did not disturb the distribution of endogenous RanGap1 as revealed by immunostaining with an anti RanGap1 (N-19) polyclonal antibody (Fig. 7). Notably, Rangap1 was not enriched in lamin A/C aggregates (Fig. 7). Since RanGAP1 is a Ran GTPase-activating protein present on the cytoplasmic side of nuclear pore complex during interphase, this result suggests that the nuclear pore complexes were correctly localized in the nuclear rim of transfected cells.

Fig. 6.

A. COS7 cell nuclei transiently co-expressing wild type or mutated lamin A and lamin C constructs. Lamins A and C were inserted into pECFP-C1 and pDsRed2-C1 fluorescent expression vectors respectively. Cells were visualized by wide-field fluorescence microscopy with excitation wavelengths of 433 nm for lamin A-FP and 558 nm for DsRed2-lamin C. Compared to the wild type, the complex lamin A/C forms aggregates and the membrane appears granular and discontinued.

B. Laser-scanning confocal microscopy of COS7 cells nuclei transiently co-transfected with either wild type or mutated lamin A and lamin C. Lamin A (in red) and lamin C (in green) were inserted into pECFP-C1 and pEYFP-C1 fluorescent expression vectors; respectively. Excitation wavelengths were 433 nm for lamin A-FP and 558 nm for DsRed2-lamin C.

Fig. 7.

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy pictures of COS7 cells nuclei transiently co-expressing wild type or mutated lamin A-FP and lamin C-FP and immunostained with the anti RanGaP1 polyclonal antibody (N-19). RanGap appears normally distributed in the nuclear envelope. Arrows indicate nuclei with R386K lamin C aggregates localized outside the nuclear envelope.

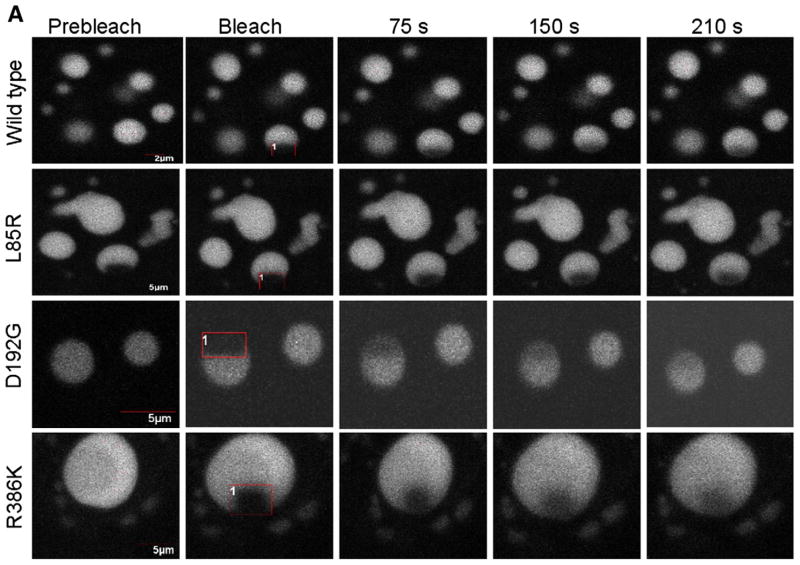

Mutated lamin C molecules present in giant aggregates exhibit increased mobility

It has been shown that some LMNA mutations are associated with an increased mobility of lamin A within the nuclear envelope [33] which indicates that some LMNA mutations affect the mobility of lamin A/C molecules. We hypothesized that the inability of lamin C mutants to properly incorporate into the nuclear envelope would reflect a different rigidity of the molecular structure of lamin C aggregates compared to the wild type. This would lead to defective connection with the nuclear envelope. To assess the mobility of the lamin C molecules inside the aggregates, we performed Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) on living COS7 cells expressing L85R, D192G, R386K or wild type lamin C-FP. A defined area of selected aggregates was bleached by a series of high-powered spot laser pulses (Fig. 8A). The recovery of fluorescence in this area was then monitored as a mean to assess the mobility of lamin C molecules within each aggregate. T-test confirmed that the time after bleaching required to recover 50% of the plateau (t1/2, half time recovery) was significantly decreased in D192G (p=0.02) or R386K (p=0.03) lamin C-FP aberrant speckles compared to wild type lamin C-FP speckles (Fig. 8B), thus revealing that the dynamics of mutated lamin C molecules is significantly higher within D192G and R386K lamin C aggregates than within wild type aggregates. In contrast, in L85R lamin C aggregates, the difference is not significant. Therefore, in comparison to the wild type, the D192G and R386K lamin C intra-aggregates molecules appeared to be more mobile which is indicative of a less stable structure of themutants. This finding was corroborated by three-minute films showing that R386K laminC-FP speckles were more prone to move and fuse to each other (data not shown). No difference was observed with L85R (Figs. 8A and B) and R482W (data not shown) aggregates compared to the wild type.

Fig. 8.

A. FRAP experiments on wild type and L85R, D192G and/or R386K lamin C nuclear aggregates of COS7 cells. The boxed regions were bleached and the fluorescence recovery was monitored over a 210 s period. B. Quantitative experiments showing normalized fluorescence recovery after photobleaching of a targeted region of the lamin C nuclear aggregates in COS7 cells. (a) The fluorescence intensity in the bleached area is expressed as a relative recovery. Error bars indicates SEM, n=7. 1 is the level of fluorescence before bleaching. (b) We assessed the time after photobleaching required for fluorescence to recover the median value between the prebleach and just after the bleach (t1/2) as a mean to reflect the dynamics of molecule.

Discussion

In order to better differentiate and define lamin A and lamin C functions, we used a cell model to express the lamins individually and then together. In view of the conflicting results in previous studies regarding the effect of LMNA mutations, we duplicated some of the experiments in COS7 cells and H9C2 rat cardiomyoblasts. Results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the phenotypes observed for the LMNA mutations selected in the study

| Variants | Diseases | Phenotypes

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamin A alone | Lamin C alone | Lamin A+C | ||

| Wild type | Homogenous distribution throughout the nuclear envelope | Numerous small intranuclear aggregates mainly in close contact with the nuclear envelope | Homogenous distribution throughout the nuclear envelope | |

| L85R | DCM | Homogenous distribution throughout the nuclear envelope similarly to the wild type | Rare intranuclear giant aggregates which may make contact with the nuclear envelope | Homogenous distribution similarly to the wild type |

| D192G | DCM | Aggregates located at the periphery of the nucleus | Rare intranuclear giant aggregation without contact with the nuclear envelope. Lamin C molecules display increased mobility. | Aberrant aggregation of lamin A/C complexes connected to the nuclear envelope |

| N195K | DCM | Aggregates located at the periphery of the nucleus | Rare intranuclear giant aggregates | |

| R386K | EDMD | Aggregates located at the periphery of the nucleus. | Rare intranuclear giant aggregates without contact with the nuclear envelope. Significant proportion of these aggregates localize outside the nuclear membrane. Lamin C molecules display increased mobility. | Aberrant aggregation of lamin A/C complexes connected to the nuclear envelope |

| R482W | FPLD | Homogenous distribution throughout the nucleus similarly to the wild type | Phenotype indistinguishable from the wild type | |

AD-EDMD: Autosomal dominant muscular dystrophy, DCM: Dilated cardiomyopathy, and FPLD: Dunningan-type familial partial lipodystrophy.

Mutated lamins A organize as nuclear envelope aggregates

Our results showed that some mutated lamin A (D192G, N195K, R386K) form abnormal aggregates when expressed alone, which is consistent with previous studies [11,26,27]. However, in contrast to previous studies reporting lamin aggregates described as intranuclear [18,25–27], we found that lamin A aggregates mainly localized at the nuclear periphery of the nucleus, suggesting that although unable to properly organize in the nuclear rim and form the lamina, lamin A mutants keep the capability of associating with the nuclear envelope. Alternatively, other mutants (L85R, R482W) behaved in a way that was indistinguishable from the wild type.

Lamin C mutants form aberrant intranucleoplasmic aggregates and lose their ability to join the nuclear envelope

We also expressed lamin C alone and showed that aberrant lamin C aggregation within the nucleoplasm is a defect common to several LMNA mutations (L85R, D192G, N195K, R386K). Interestingly, only the mutations responsible for skeletal and cardiac diseases were found to result in this atypical aggregation whereas mutation R482W involved in human lipodystrophy, did not result in noticeable abnormalities in the location or distribution of either lamin A or lamin C. This finding suggests that the pathophysiological mechanism of laminopathies with cardiac involvement is distinct from lipodystrophy and engages lamin C but not lamin A as made evident by the absence of abnormal phenotype in cells expressing lamin A with the dilated cardiomyopathy mutation L85R. Other mutations responsible for cardiomyopathy or muscular dystrophy have also been reported to result in aberrant lamin A or C aggregation such as mutations E358K, M358K [27], or R453W [25]. However, all mutations should be tested to corroborate this conclusion and determine if this lamin C aggregation inside the nucleoplasm could be regarded as a potential hallmark of laminopathies with cardiac or muscular involvement. So far, more than two hundred mutations have been reported of which most are listed in the database http://www.dmd.nl/nmdb/index.php?select_db=LMNA.

Compared to some previous reports [16–19], we sometimes obtained divergent phenotypes of cells expressing the lamin mutants. For example, Raharjo et al. showed that L85R lamin A exhibits a punctate distribution across the nuclear surface slightly different from the wild type, which opposes our results and other studies [27]. Also, N195K and R386K lamin A mutants have been shown to re-localize to the nucleoplasm [18,27,34]. These discrepancies may be explained by protocol differences such as i) the antibody used which can be directed against lamin A, lamin C, or both lamins; ii) the expression vectors used for the transfection which requires either direct or indirect immunofluorescence analysis; iii) the cell lines used (C2C12, HeLa, COS7, SW13, H9C2) since each cell type expresses different levels of endogenous A-type lamin and differently handles the expression of exogenous lamin A/C.

It is interesting to note that aberrant lamin C aggregation may also be present in a small proportion of nuclei expressing wild type lamin C. This suggests that the presence of these aggregates corresponds to a transient stage of the cell cycle. We can hypothesize that cells expressing these mutants would be longer fixed in this stage. Recently, it has been shown that the mutant lamin A involved in Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome and harboring a 50 amino acid deletion alters the cell cycle progression [35].

Furthermore, several studies have suggested that lamin A plays a key role in targeting lamin C and Emerin to the nuclear envelope [16–19]. However, recent work in embryonic fibroblasts from mice expressing lamin C only (lco) showed that lamin C and emerin are normally localized into the nuclear envelope even in the absence of lamin A [14]. Furthermore, Lmnalco/lco fibroblasts from these mice display nuclear envelope with only very minimal alterations. The extrapolation of these results to human is hazardous since mouse models often exhibit differences compared to human laminopathies [36,37]. For example, two mutated H222P alleles are necessary to develop muscular dystrophy in mice, whereas the patients are heterozygous [36]. Similarly, the clinical phenotype of LmnaL530P/L530P mice, harboring an Emery–Dreifuss mutation, is consistent with human progeria syndrome [38]. In this study, we used a cell model expressing lamin C only, and brought evidence that wild type lamin C has the capacity to establish close connections with the nuclear envelope on its own (Figs. 5Ac and B). This strongly suggests that lamin C can behave independently and that lamin A is not necessary for lamin C to be present in the nuclear envelope. This finding also argues in favor of a potential substitution of lamin A by lamin C in the nuclear envelope which is consistent with the study by Fong et al. However, it is important to note that our finding does not contradict the fact that lamin C is intranuclear when expressed alone and is re-incorporated into the nuclear lamina when expressed with lamin A, as previously reported [11,16–19]. This likely reflects that the presence of lamin C in the nuclear lamina requires a precise lamin C/lamin A stoichiometry to be respected. This may also explain why the incorporation of lamin C into the nuclear lamina proceeds via intranuclear foci [17].

Furthermore, our results showed that the lamin C mutants tested here were seldom part of the nuclear lamina (Fig. 5A). As a consequence, an altered ability of lamin C to establish connections with the nuclear envelope due to mutations in LMNA gene should also be considered to explain the major alterations of the nuclear membrane observed in cardiomyocytes from patients [11,20,22]. To further analyze the pathophysiology of laminopathies and propose a potential explanation as for why the mutant lamin C connections with the nuclear envelope is altered, we performed FRAP experiments on the nuclear aggregates formed by lamin C mutants. Our result revealed that lamin C molecules were significantly more mobile within D192G and R386K lamin C-FP intranuclear aggregates compared to the wild type, thereby indicating that these aberrant lamin C aggregates were significantly less stable. Interestingly, the increased lamin C velocity was observed only with the mutants that exhibited an altered ability to interact with nuclear envelope and that led to an abnormal aggregation in the nucleoplasm (D192G, R386K). In view of these results, we can postulate that the lamin C molecules involved in these aggregates preferably interact with each other to the detriment of the nuclear envelope. However, it would be interesting to investigate other mutants to corroborate a potential correlation between the size of intranuclear aggregates, the velocity of nuclear lamin C and its capacity to associate with the nuclear envelope. Altogether, these results provide novel insight into the pathophysiological mechanism of laminopathies.

LMNA mutations alter lamin A and C interactions with their partners but not RanGap 1 distribution

We showed that L85R lamin C aggregates exhibited neither altered stability nor altered capacity to be connected to the nuclear membrane, as opposed to D192G, N195K, and R386K mutants. These findings likely indicate that the maintenance of these properties is not correlated to the size of nuclear aggregates. However, we cannot exclude that the formation of such aberrant intranuclear accumulations did not affect other lamin A/C properties, such as the interactions with lamin A/C partners. Nuclear lamina is known to participate in the organization of nuclear pores within the nuclear membrane [39]. Since we did not find any mislocalization of RanGap1 with any of the mutants tested, we can hypothesize that the localization of nuclear pore complex within the nuclear envelope is not affected. Therefore, in our cell model, the nuclear-cytoplasm trafficking of macromolecules through the nuclear envelope is most likely unaffected by the presence of mutated lamin A/C (Fig. 7). However, further experiments have to be performed to confirm this hypothesis. Indeed, it has been shown that embryonic fibroblasts from mice lacking Atype lamin exhibited a loss of the nuclear pore protein Nup153 from one pole of the nuclei indicating exclusion of nuclear pore complex from this area [40]. Similarly, Muchir et al. found that Nup153 was absent in pole of fibroblasts from patients with type 1B limb-girdle muscular dystrophy and carrying the nonsense Y259X mutation [21]. Recently, the prelamin A Y646F mutant has been found to co-localize with nuclear pore complex in embryonic kidney (HEK-293) cells [41]. Our divergent results may be explained by the fact that the mutations we investigated are not responsible for either 1B limb-girdle muscular dystrophy or progeria and that the cell type used in our model has endogenous lamin A/C which is likely sufficient to anchor nuclear pore complexes in the nuclear envelope.

Lastly, in a previous report, we showed that lamin C nuclear aggregation results in the aberrant trapping of SUMO1, a post translational modifier of numerous proteins [11]. Among these proteins, there are several transcription factors including the cardiac specific transcription factor GATA4 [42]. Similarly, Hubner et al. demonstrated that the over-expression of lamin A mutant led to the sequestration of the lamin A/C interacting partners pRb (retinoblastoma protein) and SREBP1a (sterol responsive element binding protein 1a) into lamin A nuclear aggregates [34]. Such aberrant interactions with lamin A/C partners may also be considered as a potential pathophysiological mechanism for laminopathies.

LMNA gene mutations and the variety of human phenotypes

Defects in gene regulation and/or abnormalities in nuclear architecture causing cellular fragility are the main two hypotheses that have been proposed to explain the variability of phenotypes due to LMNA mutations [1]. Our previous study was in favor of nuclear fragility since we observed dramatic nuclear envelope discontinuity in cardiomyocytes from LMNA mutated patients [11]. Here, we better dissect the properties of each of lamins A and C specifically and show that they can be differentially affected by a given mutation. These results with others [16,18,27], clearly showed that the consequences of LMNA mutation on the cell physiology is different from one mutation to another. Therefore, we can conclude that i) the type of mutation and ii) its consequence on the unique properties of each lamin specifically, are two key factors that has to be considered in predicting the potential consequences on nuclear function. The combination of these two factors can result in multiple consequences on the cell physiology which likely contributes to explain the variability and complexity of phenotypes in human disease and may be regarded as an additional working hypothesis to explain how mutations in LMNA gene lead to so many phenotypes in humans.

Lamins A and C support conjoint and also separate functions

Lastly, we showed that connections between the nuclear envelope and some mutated lamin C-FP (D192G, R386K) are absent which is not the case with the equivalent mutated lamin A. Conversely, other mutants, such as L85R led to aberrant lamin C aggregation but did not alter lamin A organization within the nuclear envelope. The fact that a mutation has different effects on lamin A and lamin C, shows that lamins A and C have to be investigated not only together but also separately in order to betterdissect their function and specific role in the occurrence of disease. Also, this likely suggests that each protein may support distinct functions. This is in agreement with a previous study showing that lamins A and C do not play the same role in the nuclear lamina assembly characteristics [16]. In particular, the emerin-lamin A and emerin-lamin C interactions appear to be functionally different and are differently affected by some Emery–Dreifuss LMNA mutations [16]. As a conclusion, a closer look at the functions of lamins A and C specifically may allow resolution of conflicting results and may also help define genotype–phenotype correlation in laminopathies which has been difficult thus far.

Acknowledgments

The Laboratory of Genetics of Cardiac diseases is part of the John and Jennifer Ruddy Canadian Cardiovascular Genetics Centre. This research was supported by Canadian Institutes for Health Research operating grants 38054 and 65152, and by Heart and Stroke Foundation grant NA 5101 awarded to F Tesson. N Sylvius was the recipient of the fellowship awarded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario Program grant 5275 and by the Astra Zeneca/Canadian Society of Hypertension/CIHR fellowship.

References

- 1.Sylvius N, Tesson F. Lamin A/C and cardiac diseases. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2006;21:159–165. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000221575.33501.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shumaker DK, Kuczmarski ER, Goldman RD. The nucleoskeleton: lamins and actin are major players in essential nuclear functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:358–366. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hutchison CJ. Lamins: building blocks or regulators of gene expression? Nat Rev, Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:848–858. doi: 10.1038/nrm950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boguslavsky RL, Stewart CL, Worman HJ. Nuclear lamin A inhibits adipocyte differentiation: implications for Dunnigan-type familial partial lipodystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:653–663. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Constantinescu D, Gray HL, Sammak PJ, Schatten GP, Csoka AB. Lamin A/C expression is a marker of mouse and human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2006;24:177–185. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruenbaum Y, Margalit A, Goldman RD, Shumaker DK, Wilson KL. The nuclear lamina comes of age. Nat Rev, Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:21–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zastrow MS, Flaherty DB, Benian GM, Wilson KL. Nuclear titin interacts with A- and B-type lamins in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:239–249. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zastrow MS, Vlcek S, Wilson KL. Proteins that bind A-type lamins: integrating isolated clues. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:979–987. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong N, Radu G, Ju W, Brown WT. Novel progerin-interactive partner proteins hnRNP E1, EGF, Mel 18, and UBC9 interact with lamin A/C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haque F, Lloyd DJ, Smallwood DT, Dent CL, Shanahan CM, Fry AM, Trembath RC, Shackleton S. SUN1 interacts with nuclear lamin A and cytoplasmic nesprins to provide a physical connection between the nuclear lamina and the cytoskeleton. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3738–3751. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3738-3751.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sylvius N, Bilinska ZT, Veinot JP, Fidzianska A, Bolongo PM, Poon S, McKeown P, Davies RA, Chan KL, Tang AS, Dyack S, Grzybowski J, Ruzyllo W, McBride H, Tesson F. In vivo and in vitro examination of the functional significances of novel lamin gene mutations in heart failure patients. J Med Genet. 2005;42:639–647. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.023283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lammerding J, Schulze PC, Takahashi T, Kozlov S, Sullivan T, Kamm RD, Stewart CL, Lee RT. Lamin A/C deficiency causes defective nuclear mechanics and mechanotransduction. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:370–378. doi: 10.1172/JCI19670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tulac S, Dosiou C, Suchanek E, Giudice LC. Silencing lamin A/C in human endometrial stromal cells: a model to investigate endometrial gene function and regulation. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:705–711. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fong LG, Ng JK, Lammerding J, Vickers TA, Meta M, Cote N, Gavino B, Qiao X, Chang SY, Young SR, Yang SH, Stewart CL, Lee RT, Bennett CF, Bergo MO, Young SG. Prelamin A and lamin A appear to be dispensable in the nuclear lamina. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:743–752. doi: 10.1172/JCI27125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Libotte T, Zaim H, Abraham S, Padmakumar VC, Schneider M, Lu W, Munck M, Hutchison C, Wehnert M, Fahrenkrog B, Sauder U, Aebi U, Noegel AA, Karakesisoglou I. Lamin A/C-dependent localization of Nesprin-2, a giant scaffolder at the nuclear envelope. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3411–3424. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motsch I, Kaluarachchi M, Emerson LJ, Brown CA, Brown SC, Dabauvalle MC, Ellis JA. Lamins A and C are differentially dysfunctional in autosomal dominant Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Eur J Cell Biol. 2005;84:765–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pugh GE, Coates PJ, Lane EB, Raymond Y, Quinlan RA. Distinct nuclear assembly pathways for lamins A and C lead to their increase during quiescence in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 19):2483–2493. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.19.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raharjo WH, Enarson P, Sullivan T, Stewart CL, Burke B. Nuclear envelope defects associated with LMNA mutations cause dilated cardiomyopathy and Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4447–4457. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaughan A, Alvarez-Reyes M, Bridger JM, Broers JL, Ramaekers FC, Wehnert M, Morris GE, Whitfield WGF, Hutchison CJ. Both emerin and lamin C depend on lamin A for localization at the nuclear envelope. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2577–2590. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.14.2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arbustini E, Pilotto A, Repetto A, Grasso M, Negri A, Diegoli M, Campana C, Scelsi L, Baldini E, Gavazzi A, Tavazzi L. Autosomal dominant dilated cardiomyopathy with atrioventricular block: a lamin A/C defect-related disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:981–990. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01724-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muchir A, van Engelen BG, Lammens M, Mislow JM, McNally E, Schwartz K, Bonne G. Nuclear envelope alterations in fibroblasts from LGMD1B patients carrying nonsense Y259X heterozygous or homozygous mutation in lamin A/C gene. Exp Cell Res. 2003;291:352–362. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verga L, Concardi M, Pilotto A, Bellini O, Pasotti M, Repetto A, Tavazzi L, Arbustini E. Loss of lamin A/C expression revealed by immuno-electron microscopy in dilated cardiomyopathy with atrioventricular block caused by LMNA gene defects. Virchows Arch. 2003;443:664–671. doi: 10.1007/s00428-003-0865-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vigouroux C, Auclair M, Dubosclard E, Pouchelet M, Capeau J, Courvalin JC, Buendia B. Nuclear envelope disorganization in fibroblasts from lipodystrophic patients with heterozygous R482Q/W mutations in the lamin A/C gene. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4459–4468. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Herron AJ, Worman HJ. Pathology and nuclear abnormalities in hearts of transgenic mice expressing M371K lamin A encoded by an LMNA mutation causing Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2479–2489. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broers JL, Kuijpers HJ, Ostlund C, Worman HJ, Endert J, Ramaekers FC. Both lamin A and lamin C mutations cause lamina instability as well as loss of internal nuclear lamin organization. Exp Cell Res. 2005;304:582–592. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hubner S, Eam JE, Wagstaff KM, Jans DA. Quantitative analysis of localization and nuclear aggregate formation induced by GFP-lamin A mutant proteins in living HeLa cells. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:810–826. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostlund C, Bonne G, Schwartz K, Worman HJ. Properties of lamin A mutants found in Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, cardiomyopathy and Dunnigan-type partial lipodystrophy. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4435–4445. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rankin J, Ellard S. The laminopathies: a clinical review. Clin Genet. 2006;70:261–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fatkin D, MacRae C, Sasaki T, Wolff MR, Porcu M, Frenneaux M, Atherton J, Vidaillet HJ, Jr, Spudich S, De Girolami U, Seidman JG, Seidman C, Muntoni F, Muehle G, Johnson W, McDonough B. Missense mutations in the rod domain of the lamin A/C gene as causes of dilated cardiomyopathy and conduction-system disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1715–1724. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonne G, Di Barletta MR, Varnous S, Becane HM, Hammouda EH, Merlini L, Muntoni F, Greenberg CR, Gary F, Urtizberea JA, Duboc D, Fardeau M, Toniolo D, Schwartz K. Mutations in the gene encoding lamin A/C cause autosomal dominant Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1999;21:285–288. doi: 10.1038/6799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao H, Hegele RA. Nuclear lamin A/C R482Q mutation in canadian kindreds with Dunnigan-type familial partial lipodystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:109–112. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phair RD, Misteli T. High mobility of proteins in the mammalian cell nucleus. Nature. 2000;404:604–609. doi: 10.1038/35007077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilchrist S, Gilbert N, Perry P, Ostlund C, Worman HJ, Bickmore WA. Altered protein dynamics of disease-associated lamin A mutants. BMC Cell Biol. 2004;5:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hubner S, Eam JE, Hubner A, Jans DA. Laminopathy-inducing lamin A mutants can induce redistribution of lamin binding proteins into nuclear aggregates. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dechat T, Shimi T, Adam SA, Rusinol AE, Andres DA, Spielmann HP, Sinensky MS, Goldman RD. Alterations in mitosis and cell cycle progression caused by a mutant lamin A known to accelerate human aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:4955–4960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700854104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arimura T, Helbling-Leclerc A, Massart C, Varnous S, Niel F, Lacene E, Fromes Y, Toussaint M, Mura AM, Keller DI, Amthor H, Isnard R, Malissen M, Schwartz K, Bonne G. Mouse model carrying H222P-Lmna mutation develops muscular dystrophy and dilated cardiomyopathy similar to human striated muscle laminopathies. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:155–169. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mounkes LC, Kozlov SV, Rottman JN, Stewart CL. Expression of an LMNA-N195K variant of A-type lamins results in cardiac conduction defects and death in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:2167–2180. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mounkes LC, Kozlov S, Hernandez L, Sullivan T, Stewart CL. A progeroid syndrome in mice is caused by defects in A-type lamins. Nature. 2003;423:298–301. doi: 10.1038/nature01631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holaska JM, Wilson KL, Mansharamani M. The nuclear envelope, lamins and nuclear assembly. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:357–364. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan T, Escalante-Alcalde D, Bhatt H, Anver M, Bhat N, Nagashima K, Stewart CL, Burke B. Loss of A-type lamin expression compromises nuclear envelope integrity leading to muscular dystrophy. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:913–920. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan Y, Garg A, Agarwal AK. Mislocalization of prelamin A Tyr646Phe mutant to the nuclear pore complex in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;355:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Feng XH, Schwartz RJ. SUMO-1 modification activated GATA4 dependent cardiogenic gene activity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49091–49098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407494200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]