Abstract

The androgen receptor (AR) is a transcription factor that employs many diverse interactions with coregulatory proteins in normal physiology and in prostate cancer (PCa). The AR mediates cellular responses in association with chromatin complexes and kinase cascades. Here we report that the nuclear matrix protein, scaffold attachment factor B1 (SAFB1), regulates AR activity and AR levels in a manner that suggests its involvement in PCa. SAFB1 mRNA expression was lower in PCa in comparison with normal prostate tissue in a majority of publicly available RNA expression data sets. SAFB1 protein levels were also reduced with disease progression in a cohort of human PCa that included metastatic tumors. SAFB1 bound to AR and was phosphorylated by the MST1 (Hippo homolog) serine-threonine kinase, previously shown to be an AR repressor, and MST1 localization to AR-dependent promoters was inhibited by SAFB1 depletion. Knockdown of SAFB1 in androgen-dependent LNCaP PCa cells increased AR and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, stimulated growth of cultured cells and subcutaneous xenografts and promoted a more aggressive phenotype, consistent with a repressive AR regulatory function. SAFB1 formed a complex with the histone methyltransferase EZH2 at AR-interacting chromatin sites in association with other polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) proteins. We conclude that SAFB1 acts as a novel AR co-regulator at gene loci where signals from the MST1/Hippo and EZH2 pathways converge.

Keywords: AR, MST1/STK4, Hippo-RASSF1-LATS, prostate cancer, castration resistance

INTRODUCTION

The androgen receptor (AR) is a critical driver of progression to castration-resistant disease in prostate cancer (PCa).1–7 In complex with ligand, AR binds genomic androgen-response elements (AREs), which serve as platforms for recruitment of basal transcriptional machinery and coregulators. The AR mediates a transcriptional program that results in diverse, context-dependent biological outcomes.8 Coregulatory proteins act as activators or repressors of AR function,8,9 and their deregulation can promote PCa progression.10 Corepressors employ diverse mechanisms to affect AR activity, including association with chromatin-modifying proteins11 and recruitment of kinases that modify histones, chromatin remodeling factors and transcription factors.12,13

The serine-threonine kinase MST1/STK4,14 a Hippo homolog with tumor suppressor activity, was recently shown to complex with AR.15 MST1 localizes to chromatin, phosphorylates and negatively regulates AR and suppresses PCa tumor growth independently of its pro-apoptotic role.15 The two MST1 caspase cleavage products have also been shown to interact directly with and inhibit the oncogenic kinase AKT1.16,17 Consequently, MST1 is a potential node through which AR-dependent and -independent pathways might converge. The physiologic roles of kinases that modify transcription factors are still poorly understood.15

Epigenetic chromatin modifications have important roles during prostate tumorigenesis and cancer progression.18,19 PCa progression is influenced by the gene silencing complex, polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which includes the methytransferase EZH2, a protein frequently overexpressed in PCa.20 Here we demonstrate that the transcriptional repressor, scaffold attachment factor B1 (SAFB1), a chromatin-associated protein linked to repression of nuclear receptors such as estrogen receptor-α,21–23 is a novel AR repressor, an MST1 substrate and a functional partner of EZH2. Our findings suggest that SAFB1 is a component of a chromatin-modifying complex that integrates signals from the MST1/Hippo and EZH2 pathways with the AR transcription machinery.

RESULTS

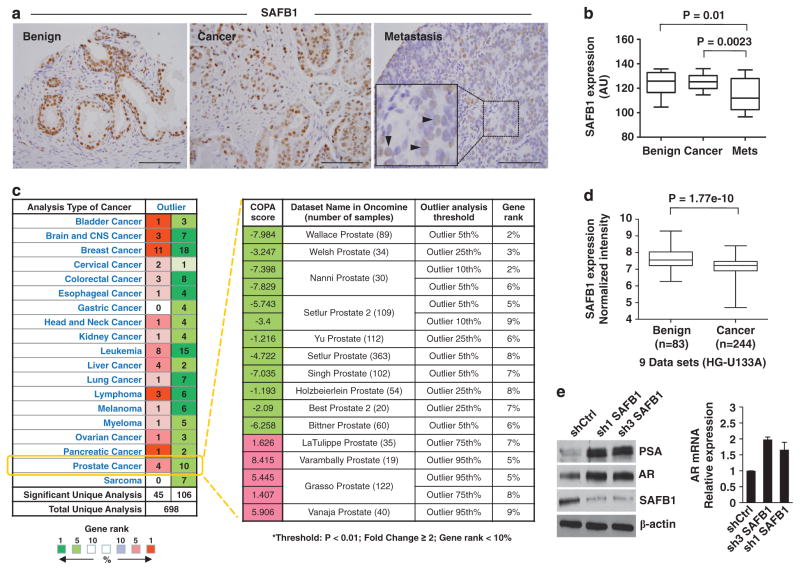

SAFB1 expression and human PCa

We initially identified SAFB1 in LNCaP PCa cells using tandem mass spectrometry as a component of an AKT1 immune complex.24 To assess the significance of this finding in the context of human PCa, we analyzed a tissue microarray (TMA) containing benign prostate tissues, organ-confined cancers and metastatic tumors using monospecific anti-SAFB1, MST1 and AKT1 antibodies. SAFB1 levels were significantly lower in metastases in comparison with both benign tissues (P = 0.01) and locally confined (P = 0.0023) tumors as determined using an automated system (Chromavision) (Figures 1a and b).25 Interestingly, the lowest levels of SAFB1 protein were detected in 8 of 13 hormone-resistant metastatic tumors (data not shown), suggesting that SAFB1 loss may be associated with lethal disease.

Figure 1.

Expression of SAFB1 in human PCa tissues, public databases and SAFB1-knockdown cells. (a) Representative images of SAFB1 immunostaining of a TMA containing benign prostate tissue, organ-confined PCa and metastases, showing downregulation of the protein in metastases. Tumor cells with absent or low expression of SAFB1 are indicated in the inset by arrowheads. Magnification: ×20. Size bar: 50 μm. (b) Quantitative analysis of SAFB1 levels in the TMA in a showing a significant reduction of protein level in metastatic tumors in comparison with benign or PCa tissues. (c) Outlier profile of SAFB1 expression in the Oncomine database. The numbers in the red and green boxes in the left panel of the table denote the number of data sets that show over- and underexpression of SAFB1, respectively. The right panel of (c) represents the COPA statistics of SAFB1 for 14 PCa data sets. (d) Boxplot displays expression pattern of SAFB1 in normal and PCa tissues. The plot represents 9 prostate cancer data sets from the GENT database containing data obtained from the Affymetrix platform (HG-U133A). (e) Stable knockdown of SAFB1 in LNCaP cells resulted in increased AR and PSA protein expression. β-Actin was used as a loading control (left panel). AR gene expression in both stable lines as determined by real-time PCR normalized to GAPDH control (right panel).

In a separate approach, we searched cancer data sets in the public domain. We assembled an outlier gene expression profile for SAFB1 with Oncomine (www.oncomine.com), which provides COPA (Cancer Outlier Profile Analysis) outlier profiles across 19 different cancer types. As shown in Figure 1c (left panel), 106 data sets out of 698 exhibited underexpression outlier profiles of the SAFB1 gene, compared with 45 data sets showing overexpression. Among 14 PCa data sets showing SAFB1 as a significant outlier, underexpression of the SAFB1 gene was detected in 10 different cancer data sets, compared with four data sets showing over-expression (Figure 1c, right panel). Using the GENT database (medicalgenome.kribb.re.kr/GENT), normalized intensities of SAFB1 mRNA for normal vs PCa were extracted for 15 PCa data sets. Among this group, six data sets were generated using the Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2 platform and nine were generated using the Affymetrix HG-U133A platform. These two groups of data were normalized separately, and differential expression of SAFB1 in PCa compared with normal tissues was evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. The boxplots in Figures 1d and Supplementary Figure S1A illustrate significant downregulation in PCa in these aggregated data. Collectively, these results suggest that SAFB1 downregulation is a frequent event in multiple cancers, and this feature is consistently observed in PCa.

In line with the above, stable knockdown of SAFB1 using shRNAs targeted to independent sites in SAFB1 mRNA in LNCaP cells resulted in an increase in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and AR mRNA and protein levels in two independent stable sublines (Figure 1e), suggesting that loss of SAFB1 expression stimulates the AR axis, consistent with a transcriptional repressor function.

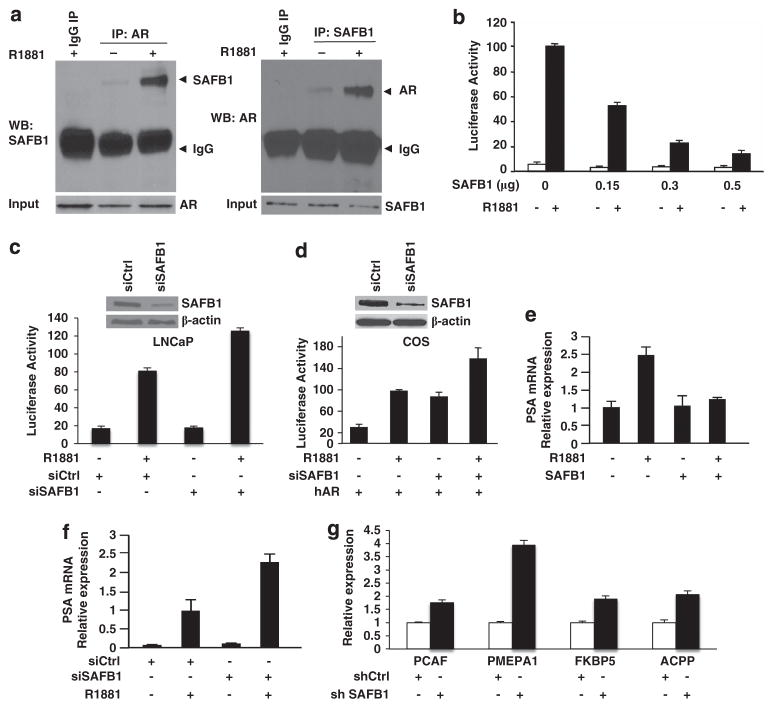

SAFB1 interacts with AR and regulates its transcriptional activity

SAFB1 has been shown to be a transcriptional repressor of estrogen receptor-α and other nuclear receptors, including PPARα/β/γ, FXRα, RORα1, VDR and LRH-1,21,23 but to our knowledge not the AR. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated the presence of a complex between endogenous AR and endogenous SAFB1 in nuclear extracts (Figure 2a). SAFB1/AR complex formation was stimulated by the nonmeta-bolizable androgen R1881, suggesting that SAFB1 is an AR coregulatory protein. AR and SAFB1 also colocalized in LNCaP cell nuclei as demonstrated with immunofluorescence cell staining (Supplementary Figure S1B).

Figure 2.

SAFB1 inhibits AR transcriptional activity and androgen-sensitive gene expression. (a) Association of AR and SAFB1 in nuclear extracts from LNCaP cells is stimulated by R1881. (b) Enforced expression of SAFB1 dose-dependently inhibited PSA promoter activity in LNCaP cells +/− 1 nM R1881 in serum-free medium. (c, d) The effects of either scrambled siRNA or SAFB1-specific siRNA on PSA promoter activity in LNCaP and COS cells (transfected with human AR). Knockdown efficiencies are shown for each experiment. (e, f) The effect of either enforced SAFB1 or silenced SAFB1 on PSA gene expression as determined by real-time PCR. (g) Expression of four androgen-regulated genes in LNCaP cells with SAFB1 stable knockdown (SAFB1-kd) vs control cells as evaluated by real-time PCR. Data are normalized to GAPDH, which was not altered in either transient siRNA transfections or in SAFB1-knockdown stable sublines.

To test whether the interaction between SAFB1 and AR has functional consequences, SAFB1 expression was enforced in LNCaP cells in the presence of a PSA promoter–luciferase reporter. Although the PSA reporter was strongly induced by the synthetic androgen R1881, enforced expression of SAFB1 markedly repressed ligand-induced AR activity in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2b). Similar results were observed in COS cells expressing enforced AR and in C4-2 cells, a hormone-independent LNCaP variant (Supplementary Figure S1C). Conversely, silencing of endogenous SAFB1 by siRNA enhanced AR activity in LNCaP cells (Figure 2c) and in COS cells transfected with AR (Figure 2d), indicating that the native protein acts in a functionally similar manner to enforced SAFB1.

In agreement with these data, enforced SAFB1 expression in LNCaP cells inhibited androgen-induced expression of PSA mRNA, whereas SAFB1 silencing caused PSA mRNA upregulation (Figures 2e and f). To assess the generality of the repressive effect of SAFB1 on AR-activated genes, we examined several additional genes shown by others to be regulated by AR—KAT2B (PCAF),26 PMEPA1,27 FKBP528 and ACPP29—in SAFB1-knockdown cells. SAFB1 silencing resulted in increased expression of all four genes, consistent with the findings obtained with PSA (Figure 2g).

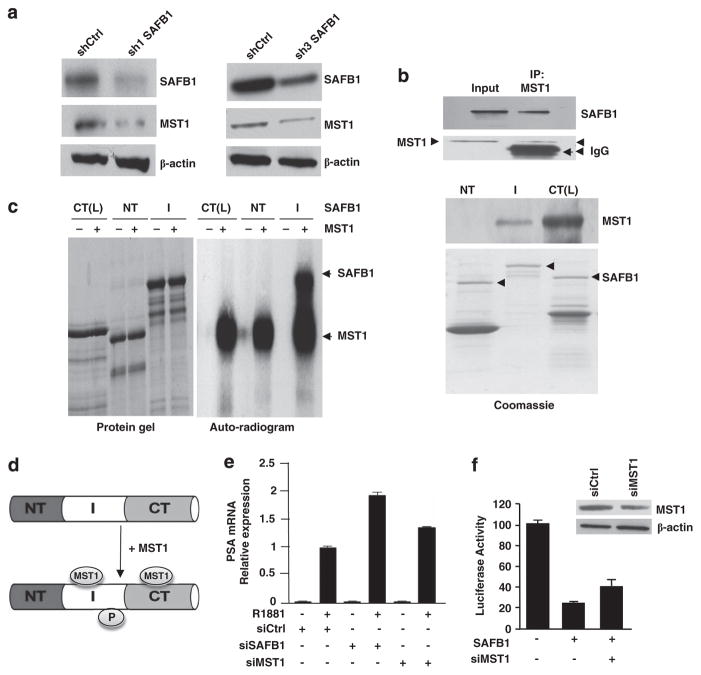

SAFB1 interacts with MST1

The serine-threonine kinase MST1 interacts with AR and inhibits AR-mediated transcription and LNCaP cell growth.15 Because MST1 cannot bind DNA directly, the functional interaction between MST1 and AR led us to hypothesize that the three proteins (SAFB1, MST1 and AR) might physically associate.

SAFB1 knockdown in LNCaP cells reduced MST1 levels in two clonal cell populations (Figure 3a), suggesting a regulatory relationship between the two proteins. SAFB1 also co-immuno-precipitated from LNCaP nuclear extracts with endogenous MST1 (Figure 3b, top panel). To determine whether MST1 and SAFB1 interact directly and whether any of the SAFB1 protein–protein interaction motifs are important for MST1 binding, GST pull-downs were performed with purified recombinant MST1 and SAFB1-GST fusion proteins. Both the intermediate (I, aa 260–600) and C-terminal (CT(L), aa 548–915) regions (Supplementary Figure S2A) were identified as MST1 interaction domains, with a notable preference for the C-terminal domain (Figure 3b). GST alone did not show any binding (not shown). A robust MST1-AR association was identified in LNCaP nuclear extracts (Supplementary Figure S2B), consistent with published results.15

Figure 3.

MST1 interacts with and phosphorylates SAFB1. (a) Effect of SAFB1 silencing on MST1 expression in two different stable clones. (b) Interaction of SAFB1 with MST1 in LNCaP cells as determined by immunoprecipitation assay (upper panel); both intermediate (I) and C-terminal domain (CT) of SAFB1 interact with MST1 (bottom panel). (c) In vitro phosphorylation of intermediate domain of GST-SAFB1 by purified recombinant MST1. Left panel: Coomassie blue staining; right panel: autoradiogram. (d) Schematic representation of MST1 interaction and phosphorylation domains on SAFB1. (e) Silencing of MST1 increased PSA gene expression in the presence and absence of R1881 (1 nM). (f) Silencing of MST1 by MST1-specific siRNA partially attenuated SAFB1-mediated repression. Knockdown efficiency is shown.

To determine whether SAFB1 is an MST1 substrate, incubation of active recombinant MST1 with SAFB1-GST fusions in the presence of [γ32P] ATP resulted in preferential phosphorylation of the SAFB1 intermediate (I) fragment (Figure 3c, right panel). GST alone did not show any phosphorylation (not shown). The observed interaction and phosphorylation domains for MST1 on SAFB1 are illustrated in Figure 3d. These data indicate that SAFB1 is an interaction partner of both AR and MST1 and that SAFB1 might function as a scaffold that recruits coregulators and mediates their binding to specific chromatin sites.

MST1 was shown previously to inhibit AR transcriptional activity.15 Consistent with this, enforced MST1 expression inhibited PSA reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Supplementary Figure S2C). MST1 silencing modestly induced endogenous PSA mRNA upregulation compared with control (Figure 3e), consistent with the luciferase reporter data. Silencing of endogenous MST1 partially attenuated SAFB1-mediated repression (Figure 3f).

Enforced SAFB1 in LNCaP cells also decreased the level of PSA protein (Supplementary Figure S2D). Conversely, siRNA depletion of SAFB1 increased PSA protein levels (data not shown), consistent with results from the stable shSAFB1 sublines (Figure 1e). Taken together, these data suggest that SAFB1 and MST1 cooperate to repress the AR.

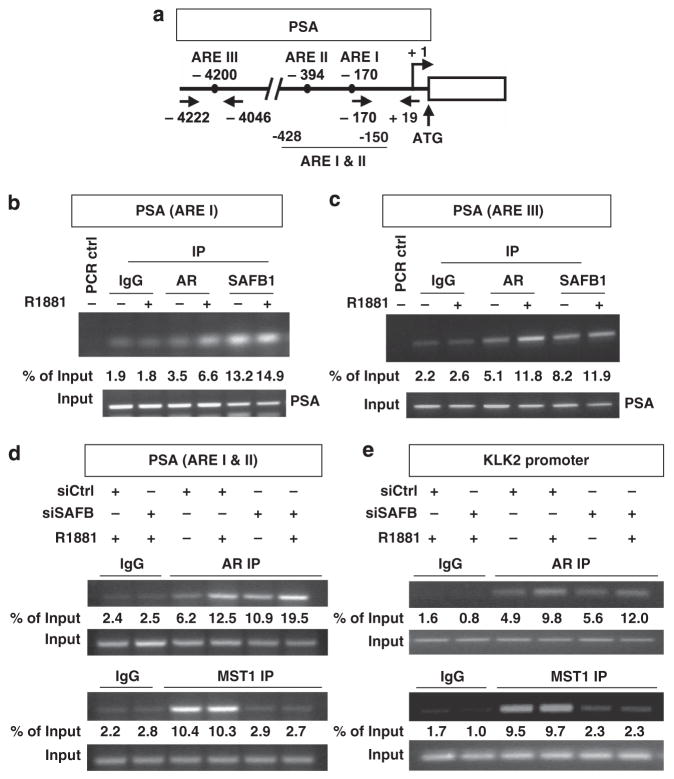

SAFB1 in complex with MST1 associates with androgen response elements

Given that SAFB1 represses AR activity, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to determine whether SAFB1 binds to androgen-regulated promoters. We tested three AREs in the PSA promoter, located at nucleotides − 170 (ARE I), −394 (ARE II) and −4200 (ARE III) (Figure 4a), all of which are involved in transcriptional regulation by androgen.30 We also analyzed the promoter of a related kallikrein gene, KLK2, which is also androgen responsive.31

Figure 4.

SAFB1 and MST1 associate with the PSA and KLK2 promoters. (a) Schematic representation of the regions of the PSA promoter used in the ChIP assays. Arrows indicate the positions of the AREs and PCR primers. (b) Localization of AR and SAFB1 proteins on the PSA promoter (ARE I) region as determined by ChIP. (c) Recruitment of SAFB1 and AR to the enhancer region of the PSA gene. (d) Recruitment of AR and MST1 to the PSA promoter (ARE I and II, −150 to −422) in the presence of silenced endogenous SAFB1. (e) Association of AR and MST1 at the KLK2 promoter (−97 to −218) in the presence of siCtrl or siSAFB1. All experiments were performed in LNCaP cells. All experiments performed in LNCaP cells were either in the presence or in the absence of 1 nM R1881.

Both AR and SAFB1 immunoprecipitates contained DNA corresponding to the amplified PSA promoter and enhancer regions (Figures 4b and c). In contrast to AR, promoter occupancy by SAFB1 was not significantly affected by androgen. SAFB1 also bound the PSA promoter in the absence of AR (Supplementary Figure S3A), an initially surprising result, although one consistent with published data showing that SAFB1 also regulates AR-independent genes.32

Both SAFB1 and MST1 were detected at the KLK2 and PSA enhancer regions (Figure 4c, Supplementary Figure S3B), consistent with published data on MST1 recruitment to the PSA promoter.15 To determine whether recruitment of MST1 to the PSA and KLK2 promoters is mediated by SAFB1, we examined the effects of SAFB1 silencing on this process. SAFB1 knockdown inhibited MST1 recruitment to both promoters, but it had no effect on association of AR with these regions (Figures 4d and e, bottom panels). This indicates that localization of MST1 to important regulatory sites within the PSA and KLK2 promoters is dependent in part on SAFB1.

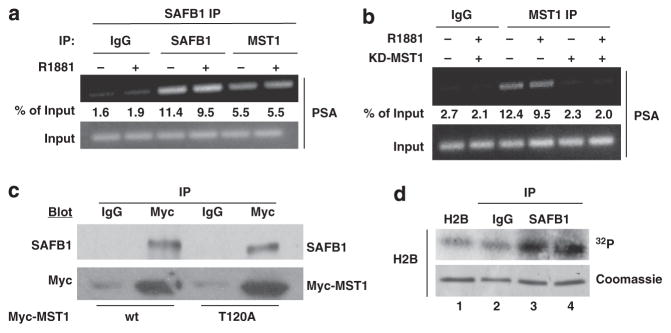

Re-ChIP experiments demonstrated that MST1 and SAFB1 assemble as a multi-protein complex on the AREs of the PSA promoter (Figure 5a). A schematic representation of the region of the PSA promoter used in the re-ChIP experiment is shown in Supplementary Figure S3C. Enforced expression of a kinase-inactive MST1 mutant (K59R), which inhibits MST1 activity in vivo,33 blocked binding of MST1 to the PSA promoter (Figure 5b), suggesting that efficient association of MST1 with chromatin may require kinase activity. A recent study showed that phosphorylation of nuclear MST1 at threonine-120 reduces its activity.34 In order to assess whether SAFB1 can interact with this phosphorylation-deficient (active) form of nuclear MST1, we transfected wild-type MST1 and MST1(T120A) into LNCaP cells and examined their association with SAFB1. Both the wild-type and T120A mutant MST1 forms bound SAFB1 with similar efficiency, indicating that SAFB1 interacts with both active forms of MST1 (Figure 5c). In order to test whether the SAFB1 chromatin complex can phosphorylate a known MST1 chromatin substrate,35 we asked whether histone H2B could be phosphorylated by chromatin immunoprecipitated with SAFB1. The SAFB1 chromatin complex phosphorylated H2B in an in vitro kinase assay (Figure 5d), consistent with the conclusion that SAFB1 forms a complex with active kinases.

Figure 5.

SAFB1 and active MST1 are present in the same complex. (a) Re-ChIP indicated that MST1 was present in the same SAFB1 complex, independently of treatment with androgen. (b) MST1 kinase activity is required for association with chromatin. Ethidium bromide staining after ChIP-PCR. (c) Association of nuclear SAFB1 with transfected Myc tagged wild-type (wt) and MST-T120A mutant. IgG IP was used as a negative control. (d) The SAFB1 chromatin complex phosphorylated histone H2B in vitro. The crosslinked chromatin complex was immunoprecipitated using an SAFB1 antibody, and the kinase assay was performed with purified histone H2B as a substrate (compare lanes 1 and 2 with 3 and 4). Lanes 3 and 4 show the duplicate assay. Coomassie blue-stained histone bands showed comparable starting materials.

Repression of gene expression by SAFB1 coincides with histone modification

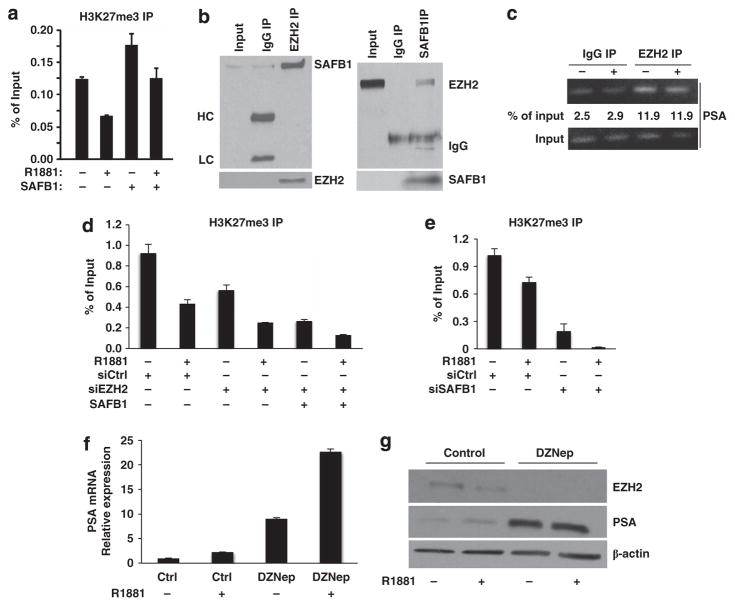

Certain kinases, including MST1, have been reported to be involved in chromatin organization.36–38 Consequently, we examined whether the effect of SAFB1 on gene silencing occurs coincident with covalent histone modification. Three lysine methylation sites are associated with transcriptional repression: H3K9, H3K27 and H4K20. H3K27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) has been implicated in the silencing of many genes.39,40 In order to assess whether H3K27 trimethylation is involved in SAFB1-mediated gene repression, we examined the effect of enforced SAFB1 on H3K27 methylation status in LNCaP cells. Under these conditions, ChIP revealed a significant enrichment of H3K27me3 on the PSA promoter in the absence of R1881 (Figure 6a). Under conditions of enforced SAFB1, the level of H3K27me3 associated with the repressed PSA gene was increased. Total histone H3 density was similar after SAFB1 expression (not shown), indicating that the observed hypermethylation was not because of histone density discrepancies.

Figure 6.

SAFB1-mediated gene repression is linked to histone modification. (a) Effect of enforced expression of SAFB1 on H3K27 trimethylation status at the PSA promoter. qPCR after ChIP assay. (b) Association of PRC2 complex protein EZH2 with SAFB1 in LNCaP nuclei as determined by immunoprecipitation. (c) PSA promoter occupancy by EZH2 using PSA primers (−150 to −422). (d) Effect of EZH2 silencing on H3K27 methylation status of the endogenous PSA promoter in the presence and absence of forced expression of SAFB1; ChIP assay followed by qPCR analysis. Effect of knockdown of EZH2 on EZH2 protein is shown in Supplementary Data (Supplementary Figure S3). (e) Silencing of endogenous SAFB significantly reduced the H3K27me3 accumulation on the PSA promoter. (f) LNCaP cells (24 h culture) were first grown in the presence of vehicle/3 μM DZNep for 48 h in serum-free condition before vehicle/R1881 (1 nM) was added for 24 h. Gene expression was monitored by qPCR normalized to GAPDH. (g) PSA protein expression was determined by western blot analysis of the same samples prepared simultaneously (lower panel). DZNep effects on EZH2 expression are shown (G, upper panel).

EZH2 is the major histone methyltransferase known to trimethylate histone H3 on lysine 27 in vivo and is the only enzymatic subunit of the PRC2 repressive complex.41 In order to determine whether the SAFB1-induced H3K27 trimethylation involves EZH2, we attempted to co-immunoprecipitate SAFB1 and EZH2 from LNCaP nuclear extracts. The results identified EZH2 and SAFB1 in the same immune complex (Figure 6b).

ChIP performed with EZH2 immunoprecipitates showed that EZH2 can occupy the PSA promoter (Figure 6c). In order to understand whether EZH2 is essential for the increase in H3K27me3 accumulation on chromatin, we silenced endogenous EZH2 in LNCaP cells (Supplementary Figure S3D). This resulted in a decrease in the level of H3K27me3 on the PSA promoter even in the presence of SAFB1 (Figure 6d). As a complementary approach, we analyzed the extent of H3K27me3 after SAFB1 knockdown. Silencing of SAFB1 substantially reduced the accumulation of H3K27me3 on the PSA promoter in the presence and absence of androgen (Figure 6e and Supplementary Figure S3E).

A recent study described a significant effect of the selective EZH2 inhibitor 3-Deazaneplanocin A (DZNep) on PSA gene expression in AR-positive VCaP cells.42 Surprisingly, the same study found only a marginal effect when LNCaP cells were treated with DZNep. Here, we tested the effect of DZNep on PSA gene and protein expression in LNCaP cells under our conditions. Both in 10% serum containing normal growth conditions (Supplementary Figure S3F) and under serum starvation, DZNep enhanced PSA gene and protein expression (Figures 6f and g). Taken together, these results suggest that EZH2 acts as an AR transcription inhibitor in LNCaP cells under conditions in which SAFB1 acts as a transcriptional repressor of AR.

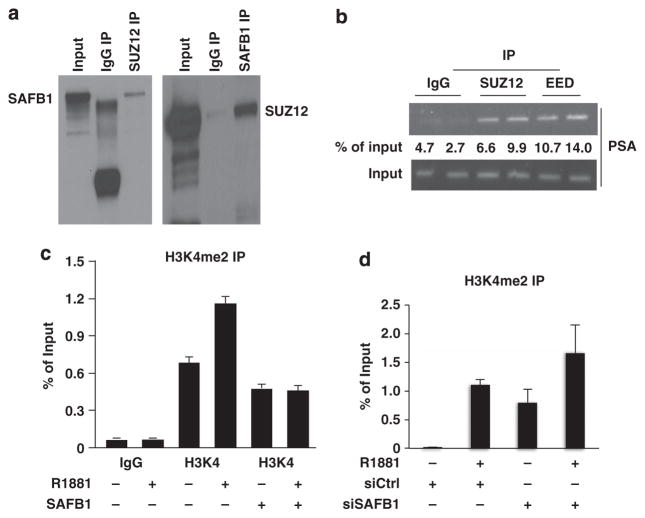

Two other core components of the PRC2 complex, SUZ12 and EED, have been described as essential EZH2 partners under conditions in which the complex acts to repress gene expression.40,43 Immunoprecipitation using an anti-SUZ12 antibody coprecipitated SAFB1, and, conversely, an anti-SAFB1 antibody coprecipitated SUZ12 (Figure 7a). Moreover, EED IP also precipitated SAFB1 from LNCaP nuclear extracts (not shown), indicating that all three essential components of the PRC2 complex associate with SAFB1. RBAP-46/48, an occasional EZH2 partner, was not detected in the SAFB1 complex (not shown). ChIP also confirmed the presence of SUZ12 and EED on the PSA promoter (Figure 7b), indicating that all the core members of the PRC2 complex co-localize with SAFB1 on a classical AR-regulated promoter region.

Figure 7.

Association with PRC2 complex and effect on histone modification. (a) Association of SAFB1 and SUZ12 as shown by reverse immunoprecipitation assay. (b) PSA promoter occupancy by SUZ12 and EED using the PSA primers (I & II) as indicated. (c) Enforced expression of SAFB1 inhibited formation of dimet-H3K4 on the endogenous PSA promoter as determined by qPCR analysis after ChIP. (d) Silencing of SAFB1 induced H3K4me2 accumulation at the PSA promoter both in the presence and in the absence of R1881.

Histone methylation can either activate or repress transcription. In contrast to H3K27 trimethylation, H3K4 di/tri methylation is generally an activation mark.44 Enforced SAFB1 decreased the level of dimethylated H3K4 on the PSA promoter (Figure 7c). Conversely, SAFB1 silencing increased the H3K4me2 level on the PSA promoter (Figure 7d). Taken together, these findings indicate that repression of androgen-sensitive gene expression by SAFB1 occurs coordinately with changes in multiple histone marks and that SAFB1 is probably a mediator of some of these chromatin modifications.

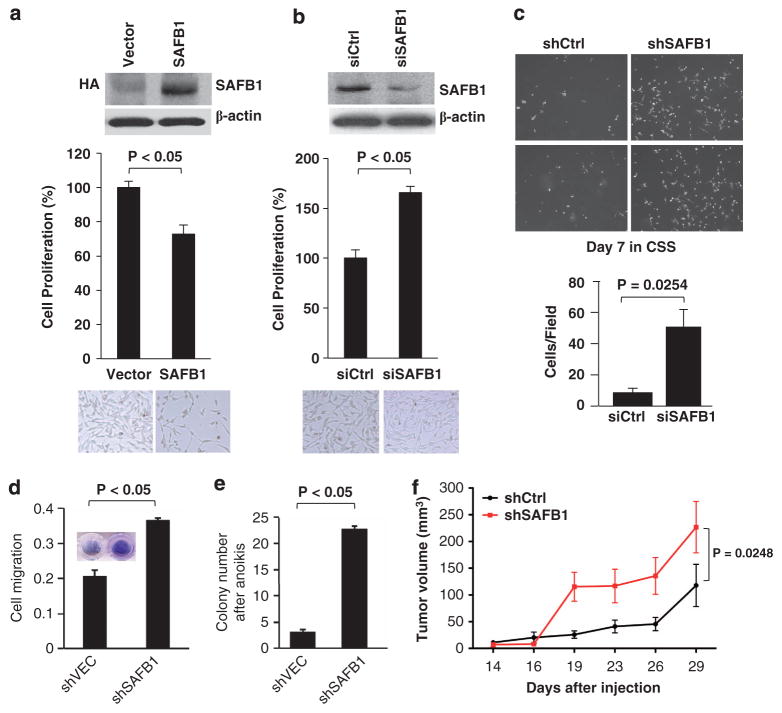

SAFB1 knockdown results in an aggressive phenotype

Consistent with the trend toward decreased SAFB1 levels seen in human PCa specimens during disease progression, enforced SAFB1 suppressed LNCaP cell proliferation (Figure 8a). Conversely, transient knockdown of SAFB1 resulted in an increase in cell growth, indicating that SAFB1 is a PCa cell growth inhibitor (Figure 8b). Enforced SAFB1 also suppressed growth of AR-negative PC3 cells (Supplementary Figure S4A), indicating that AR is probably not required for the growth suppressive effect. Enforced SAFB1 also increased the levels of the cell cycle inhibitors p21/Cip1 and p27/Kip1 (Supplementary Figure S4B), consistent with cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 phase.

Figure 8.

Effect of alterations in SAFB1 expression on LNCaP cell properties. (a) Enforced expression of SAFB1 inhibited LNCaP cell proliferation. Expression of HA-tagged SAFB1 is shown in the inset. (b) Silencing of endogenous SAFB1 (inset) enhanced LNCaP cell proliferation. (c) SAFB1 knockdown increased growth in steroid-depleted medium (supplemented with charcoal-stripped serum (CSS) over 7 days). (d) SAFB1 knockdown enhanced migration of LNCaP cells through collagen-coated transwells. (e) SAFB1 knockdown resulted in resistance to anoikis. (f) SAFB1 knockdown increased the growth rate of LNCaP subcutaneous xenografts, as shown by increased tumor volume in the animals injected with shSAFB1 cells in comparison with control cells (P = 0.0248 vs shCtrl).

LNCaP cells in which SAFB1 was stably knocked down (shSAFB1) were less growth inhibited in androgen-depleted medium in comparison with control (shCtrl) cells (Figure 8c), suggesting a phenotypic change toward hormone-independent growth. SAFB1-knockdown cells also demonstrated increased clonal growth and anchorage-independent colony formation in comparison with shCtrl cells (data not shown). The knockdown cells migrated more rapidly through collagen-coated transwells (Figure 8d) and were more resistant to anoikis (detachment-induced apoptosis) (Figure 8e). In comparison with shCtrl cells, SAFB1-knockdown cells gave rise to larger tumors when implanted as subcutaneous xenografts in intact male nude mice (Figure 8f). SAFB1-silenced cells did not grow in castrated mice (not shown), indicating that they remained androgen dependent. Collectively, these data show that SAFB1 can exert a tumor-suppressive activity in hormone-sensitive PCa cells, consistent with the most frequent pattern of expression changes seen in human prostate tumors.

DISCUSSION

We previously reported that the growth inhibitory kinase, MST1, a Hippo homolog and component of the Hippo-RASSF1-LATS tumor suppressor pathway, is an AR interacting protein and a negative regulator of AR transcriptional activity.15 In that study, we proposed a model suggesting that MST1 effects on AR may result from interaction with one or more unknown proteins that interact directly with chromatin. In the present study, we demonstrate that the chromatin scaffold protein SAFB1 interacts with and is phosphorylated by MST1 and is a novel regulator of AR capable of integrating signaling between the AR and MST1 networks. SAFB1 was originally identified by its ability to bind to scaffold/matrix attachment regions (S/MARs) and to repress transcription from the hsp27 promoter.21,23,45,46 SAFB1 has been linked to a variety of cellular processes, including transcription, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, differentiation and stress responses.22 New findings presented in the present study suggest that SAFB1 is a novel point of intersection for multiple upstream signaling mechanisms in human PCa, including signals that modify chromatin to control gene expression.

Analysis of publicly available microarray data sets indicates a significant tendency toward downregulation of expression in tumors in comparison with normal tissue (Figure 1). Analysis of SAFB1 protein levels in a TMA that contains metastatic tumors also showed downregulation with progression to metastatic disease. Eight out of 13 (>60%) hormone-resistant metastatic tumors that we analyzed at the protein level were negative for SAFB1 (data not shown). In functional tests, stable downregulation of SAFB1 in LNCaP cells resulted in a more aggressive phenotype, including increased expression of AR and PSA, enhanced resistance to androgen withdrawal and anoikis, increased migration through collagen, and stimulation of tumor growth in vivo. The trend toward downregulation was also seen across multiple tumor types, suggesting that SAFB1 loss may occur in other cancers. Because SAFB1 interacts with chromatin at sites that may not contain AREs,32 regulatory consequences of changes in expression of this protein are likely to extend to a range of binding sites across the genome and be relevant in other physiologic settings.

An increase in AR expression coincides with resistance to antiandrogen therapy1 and may compensate for low levels of androgen.47 Although SAFB1-knockdown LNCaP cells did not grow in castrated hosts, the observations that AR expression and activity were constitutively increased as a result of SAFB1 silencing and that SAFB1-knockdown cells were more aggressive phenotypically and resisted growth inhibition in androgen-depleted medium suggest an association between SAFB1 downregulation and disease progression. Our findings on the role of SAFB1 as an AR corepressor are broadly consistent with previous reports about this protein. SAFB1 was discovered in breast cancer cells, binds and inhibits ER-α and was proposed to be a tumor suppressor in this context.48 The SAFB1 gene resides at 19p13, a triple negative-specific breast cancer susceptibility locus that undergoes one of the highest rates of loss of heterozygosity reported in breast cancer.49 Interestingly, 19p13.1-p13.3 has been proposed to contain a tumor suppressor gene relevant to human PCa.50,51 Our findings here identify SAFB1 (at 19p13.3-p13.2) as a candidate tumor suppressor within this region.

We also present evidence that SAFB1 inhibits AR by a mechanism that involves histone modification. Histone modifica-tions have critical roles in prostate tumorigenesis and progression.19 We investigated the potential involvement of the polycomb repressive complex PRC2 in epigenetic gene silencing at SAFB1-repressed loci. We showed that SAFB1 physically associates with EZH2, the catalytic PRC2 subunit, and that manipulation of SAFB1 expression altered levels of H3K27me3 within a SAFB1 binding region at the endogenous PSA promoter. SAFB1 also physically associated with EED and SUZ12, two EZH2 binding partners. Moreover, all three PRC2 proteins also bind to the PSA promoter. These data suggest that the PRC2 complex has a role in the repressive actions of SAFB1 at the AR-interacting sites we analyzed. Additional studies are necessary to determine how applicable these findings are to other SAFB1 binding sites throughout the genome.

In summary, our results indicate that SAFB1 is a physiologically relevant AR coregulator, a novel nuclear target of the growth-repressive kinase MST1, and a novel functional partner of EZH2 and the PRC2 complex. Our study suggests that SAFB1 and its associated proteins represent an important node for the integration of signals through multiple oncogenic and tumor suppressor pathways in PCa and possibly other malignancies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

R1881 was from Sigma Chemical Co. DZNep was from Cayman Chemical Company. Antibodies AR and α-tubulin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnol-ogy. Lamin, MST1, AKT1, p21/Cip1, p27/Kip1, EZH2, EED, SUZ12, H3K4me2 and H3K27me3 were from Cell Signaling Technology. HA was from Covance Inc. The SAFB1 antibody and recombinant MST1 were from Upstate Biotechnology. The ECL detection kit was from New England Nuclear. The real-time PCR kit was from SA Biosciences.

Cell culture

LNCaP and C4-2 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640, whereas PC3 and COS cells were cultured in DMEM. Media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2% glutamine and 1% antibiotics.

Plasmids

SAFB1 constructs (wild type, c-terminal and GST-fusion proteins22), prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-Luc reporter,30 hAKT1, MST1 constructs 16 and human AR expression plasmid30 have been described earlier. GST-C-SAFB (CT-L, 548–915) was generated using an EcoR1-fragment from pSG5-SAFB-HA46 by ligation into pGex4T-1.

RNA silencing

ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA oligonucleotides were designed to target different splice variants of SAFB1. Controls were scrambled sequences. For the generation of SAFB1-silenced stable variant of LNCaP cells, we used transduction-ready MISSION shRNA lentiviral particles from Sigma. We tested five different hairpins (NM_002967). As a control, we used MISSION non-target shRNA lentiviral particles. LNCaP parental cells were first infected with lentivirus, followed by selection with puromycin. SAFB1, MST1 and EZH2, and ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA oligonu-cleotides (Dharmacon), designed to target different splice variants of the specified genes, were used for transient silencing.

Transfections and luciferase assays

Nucleofector (Lonza) was used to electroporate 2–4 μg of human SAFB1 plasmid/control vector or 100 nM of each siRNA/control siRNA according to the manufacturer’s protocols in all gene expression experiments, as well as to determine the effect of SAFB1 by enforced expression including cell proliferation. Transient transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen)52 in case of luciferase assay. All experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated three times using different DNA preparations.

Subcellular extracts

Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were prepared as describedin Mukhopadhyay et al.52

Tissue immunohistochemistry

The human prostate TMA consisted of benign tissues (n = 18), as well as locally confined (n = 36) and metastatic PCa (n = 36). Metastases consisted of 18 lymph node hormone-naïve (HN) and 18 hormone (castrate)-resistant (HR) distant metastases. A pathologist (D.D.V.) excluded cases if adequate tumor tissue was not available; consequently, a total of 18 benign, 21 organ-confined tumor and 21 (7 HN and 13 HR) metastases were included in the analysis. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 5-μm sections using the avidin–biotin procedure and analyzed using the ACIS System (ChromaVision). SAFB1 levels were correlated to levels of AKT1, p-AKT and MST1, previously analyzed on the same cohort.16 Expression levels among diagnostic groups were assessed by means of the t-test for unpaired data. To assess potential correlations, intensity mean values were dichotomized, and Fisher’s exact test was applied on contingency tables. All P-values were considered two-tailed, and 0.05 was used as the upper threshold for statistical significance. Origin 8 software (OriginLab Corporation) was used for statistical analysis.

Proliferation and colony formation assay

Transfected cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 1 × 104/well (for proliferation assay) or in 150 mm plates at 1 × 102/well (for colony formation assay). Cells were stained with crystal violet and counted 3 or 7 days later, respectively.53

Anchorage-independent soft agar growth assay

Transfectants were seeded at 1 × 104 in 3 ml 0.35% agar in RPMI/FBS and overlaid on 2 ml of 0.7% agar in RPMI/FBS in six-well plates. MTT-stained colonies were counted at 14 days and images were captured using a Zeiss microscope.53

Migration assay

Stably transfected cells (3 × 105 cells/ml) were seeded in collagen-coated inserts (Millipore). Sixteen hours later, cells that had invaded to the bottom surface of the inserts were stained with crystal violet. After extraction with 10% acetic acid, absorbance was read using a FLUOstar reader.53

Xenografts

Control and SAFB1-silenced cells were inoculated subcutaneously in Matrigel into 12 nude mice (male nu/nu mouse, 6 w old, Charles River). A total of 2 × 106 cells in 100 μl volume were used per injection per site (4 sites/mouse; n = 24 sites per condition). Tumor volumes were measured using an automatic caliper every 2–3 days. The Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the study.

Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis

Protein (4–500 μg) was immunoprecipitated with specific antibodies with either protein A or G-Sepharose beads. Bead-bound complexes were immunodetected as described.52 Dilutions for primary antibodies were 1:1000 for AR, HA, SAFB1, AKT1, MST1, EZH2, EED, SUZ12 and Lamin and 1:10 000 for PSA and β-actin. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were used at 1:5000 dilution. Detection was performed using chemiluminescence.

Glutathione S-transferase pull-down

GST-SAFB1 fusion proteins expressed in bacteria were adsorbed to glutathione-Sepharose beads, incubated with purified recombinant MST1 in binding buffer (20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 137 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% NP40) for 60 min at 4 °C and analyzed by western blotting.30

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

ChIP was performed using the ChIP Assay Kit (Upstate Biotechnology). PCR was performed for 34 cycles consisting of 1 min denaturation at 95 °C, 1.5 min annealing at 62 °C and 1.5 min elongation at 72 °C.30 For re-ChIP experiments, extraction was performed in 20 mM DTT instead of SDS/NaHCO3 buffer.

Real-time PCR

RNA was isolated using the RNeasyMini kit (Qiagen), and cDNA synthesis was performed using SuperScript (Invitrogen). Gene expression was monitored by qPCR (SA Biosciences) using the SYBR green method. Sense and antisense primer sets are as follows: PSA, 5′-AGAACAGCAAGTGCTAGCTC-3′ and 5′-AGGTGGTAAGCTTGGGGCTG-3′; FKBP5, 5′-AAAAGGCCAAGGAGCACAAC-3′ and 5′-TTGAGGAGGGGCCGAGTTC-3′; ACPP, 5′-CATCTGGAATCCTATCCTACTCTG-3′ and 5′-AGTTCTTGAAAACGAGGGCA-3′; PCAF, 5′-CTGGAGGCACCATCTCAACGAA-3′ and 5′-ACAGTGAAGACCGAGCGAAGCA-3′; PMEPA1, 5′-CATGATCCCCGAGCTGCT-3′ and 5′-TGATCTGAACAAACTCCAGCTCC-3′; GAPDH, 5′-CGATGCTGGCGCTGAGTA and 5′-CGTTCAGCTCAGTGACC-3′; AR, 5′-GCCTTGCTCTCTAGCCTCAA-3′ and 5′-GTCGTCCACGTGTAAGTTGC-3′. For ChIP-PCR data, percentage of input was calculated from signals obtained from ChIP divided by the signals obtained from the input. Samples for Q-PCR were analyzed in triplicate relative to the internal standard GAPDH RNA.

Kinase assay

For determination of in vitro phosphorylation of SAFB1 fusion proteins by recombinant MST1 kinases (50–100 ng/reaction), GST-SAFB1 fragments were incubated with 5 μCi [g – 32P] ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) and 100 μM cold ATP in kinase buffer (25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT) in a volume of 30 μl and incubated at 30 °C for 20 min. Samples were resolved by gel electrophoresis and exposed to X-ray film.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. wherever necessary. Student’s t-test (two-tailed) was used between the data pairs where appropriate. Either exact P-value or a P-value of 0.05 or less was considered significant and has been used. Significance of differential expression was calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Roberts (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) for critical comments and Delia Lopez, Kristine Pelton and Paul Guthrie for technical assistance. This study was supported by NIH 1R01CA143777, 1R01CA112303, and US Department of Defense PC093459 (to MRF), NIH 5R00CA131472 (to DDV) and NIH R01 CA097213 (to SO).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

References

- 1.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, Baek SH, Chen R, Vessella R, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat Med. 2004;10:33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Debes JD, Tindall DJ. Mechanisms of androgen-refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1488–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grossmann ME, Huang H, Tindall DJ. Androgen receptor signaling in androgen-refractory prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1687–1697. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.22.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hara T, Nakamura K, Araki H, Kusaka M, Yamaoka M. Enhanced androgen receptor signaling correlates with the androgen-refractory growth in a newly established MDA PCa 2b-hr human prostate cancer cell subline. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5622–5628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scher HI, Sawyers CL. Biology of progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: directed therapies targeting the androgen-receptor signaling axis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8253–8261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taplin ME, Balk SP. Androgen receptor: a key molecule in the progression of prostate cancer to hormone independence. J Cell Biochem. 2004;91:483–490. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hara T, Miyazaki H, Lee A, Tran CP, Reiter RE. Androgen receptor and invasion in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1128–1135. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hermanson O, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Nuclear receptor coregulators: multiple modes of modification. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:55–60. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00527-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robyr D, Wolffe AP, Wahli W. Nuclear hormone receptor coregulators in action: diversity for shared tasks. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:329–347. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.3.0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knudsen KE, Penning TM. Partners in crime: deregulation of AR activity and androgen synthesis in prostate cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burd CJ, Morey LM, Knudsen KE. Androgen receptor corepressors and prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:979–994. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baek SH. When signaling kinases meet histones and histone modifiers in the nucleus. Mol Cell. 2011;42:274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vicent GP, Nacht AS, Font-Mateu J, Castellano G, Gaveglia L, Ballare C, et al. Four enzymes cooperate to displace histone H1 during the first minute of hormonal gene activation. Genes Dev. 2011;25:845–862. doi: 10.1101/gad.621811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Creasy CL, Chernoff J. Cloning and characterization of a member of the MST subfamily of Ste20-like kinases. Gene. 1995;167:303–306. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00653-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cinar B, Collak FK, Lopez D, Akgul S, Mukhopadhyay NK, Kilicarslan M, et al. MST1 is a multifunctional caspase-independent inhibitor of androgenic signaling. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4303–4313. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cinar B, Fang PK, Lutchman M, Di Vizio D, Adam RM, Pavlova N, et al. The pro-apoptotic kinase Mst1 and its caspase cleavage products are direct inhibitors of Akt1. EMBO J. 2007;26:4523–4534. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cinar B, Mukhopadhyay NK, Meng G, Freeman MR. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase-independent non-genomic signals transit from the androgen receptor to Akt1 in membrane raft microdomains. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29584–29593. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li LC, Carroll PR, Dahiya R. Epigenetic changes in prostate cancer: implication for diagnosis and treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:103–115. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Z, Wang L, Wang Q, Li W. Histone modifications and chromatin organization in prostate cancer. Epigenomics. 2010;2:551–560. doi: 10.2217/epi.10.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crea F, Hurt EM, Mathews LA, Cabarcas SM, Sun L, Marquez VE, et al. Pharmacologic disruption of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 inhibits tumorigenicity and tumor progression in prostate cancer. Molecular cancer. 2011;10:40. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garee JP, Oesterreich S. SAFB1’s multiple functions in biological control-lots still to be done! J Cell Biochem. 2010;109:312–319. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Townson SM, Kang K, Lee AV, Oesterreich S. Structure-function analysis of the estrogen receptor alpha corepressor scaffold attachment factor-B1: identification of a potent transcriptional repression domain. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26074–26081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Debril MB, Dubuquoy L, Feige JN, Wahli W, Desvergne B, Auwerx J, et al. Scaffold attachment factor B1 directly interacts with nuclear receptors in living cells and represses transcriptional activity. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;35:503–517. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mukhopadhyay NK, Kim J, Cinar B, Ramachandran A, Hager MH, Di Vizio D, et al. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K is a novel regulator of androgen receptor translation. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2210–2218. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Vizio D, Morello M, Sotgia F, Pestell RG, Freeman MR, Lisanti MP. An absence of stromal caveolin-1 is associated with advanced prostate cancer, metastatic disease and epithelial Akt activation. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2420–2424. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.15.9116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Yeh S, Wu G, Hsu CL, Wang L, Chiang T, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel androgen receptor coregulator ARA267-alpha in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40417–40423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu LL, Shanmugam N, Segawa T, Sesterhenn IA, McLeod DG, Moul JW, et al. A novel androgen-regulated gene, PMEPA1, located on chromosome 20q13 exhibits high level expression in prostate. Genomics. 2000;66:257–263. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magee JA, Chang LW, Stormo GD, Milbrandt J. Direct, androgen receptor-mediated regulation of the FKBP5 gene via a distal enhancer element. Endocrinology. 2006;147:590–598. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li SS, Sharief FS. The prostatic acid phosphatase (ACPP) gene is localized to human chromosome 3q21-q23. Genomics. 1993;17:765–766. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukhopadhyay NK, Cinar B, Mukhopadhyay L, Lutchman M, Ferdinand AS, Kim J, et al. The zinc finger protein ras-responsive element binding protein-1 is a cor-egulator of the androgen receptor: implications for the role of the Ras pathway in enhancing androgenic signaling in prostate cancer. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2056–2070. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawrence MG, Lai J, Clements JA. Kallikreins on steroids: structure, function, and hormonal regulation of prostate-specific antigen and the extended kallikrein locus. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:407–446. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammerich-Hille S, Kaipparettu BA, Tsimelzon A, Creighton CJ, Jiang S, Polo JM, et al. SAFB1 mediates repression of immune regulators and apoptotic genes in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3608–3616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto S, Yang G, Zablocki D, Liu J, Hong C, Kim SJ, et al. Activation of Mst1 causes dilated cardiomyopathy by stimulating apoptosis without compensatory ventricular myocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1463–1474. doi: 10.1172/JCI17459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collak FK, Yagiz K, Luthringer DJ, Erkaya B, Cinar B. Threonine-120 phosphoryla-tion regulated by phosphoinositide-3-kinase/Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin pathway signaling limits the antitumor activity of mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23698–23709. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.358713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheung WL, Ajiro K, Samejima K, Kloc M, Cheung P, Mizzen CA, et al. Apoptotic phosphorylation of histone H2B is mediated by mammalian sterile twenty kinase. Cell. 2003;113:507–517. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu Y, Liu Z, Yang SJ, Ye K. Acinus-provoked protein kinase C delta isoform activation is essential for apoptotic chromatin condensation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:2035–2046. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu Y, Yao J, Liu Z, Liu X, Fu H, Ye K. Akt phosphorylates acinus and inhibits its proteolytic cleavage, preventing chromatin condensation. EMBO J. 2005;24:3543–3554. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ura S, Nishina H, Gotoh Y, Katada T. Activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway by MST1 is essential and sufficient for the induction of chromatin condensation during apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5514–5522. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00199-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beisel C, Paro R. Silencing chromatin: comparing modes and mechanisms. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:123–135. doi: 10.1038/nrg2932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross PJ, Ragina NP, Rodriguez RM, Iager AE, Siripattarapravat K, Lopez-Corrales N, et al. Polycomb gene expression and histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation changes during bovine preimplantation development. Reproduction. 2008;136:777–785. doi: 10.1530/REP-08-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varambally S, Dhanasekaran SM, Zhou M, Barrette TR, Kumar-Sinha C, Sanda MG, et al. The polycomb group protein EZH2 is involved in progression of prostate cancer. Nature. 2002;419:624–629. doi: 10.1038/nature01075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chng KR, Chang CW, Tan SK, Yang C, Hong SZ, Sng NY, et al. A transcriptional repressor co-regulatory network governing androgen response in prostate cancers. EMBO J. 2012;31:2810–2823. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aldiri I, Vetter ML. Characterization of the expression pattern of the PRC2 core subunit Suz12 during embryonic development of Xenopus laevis. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2009;238:3185–3192. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinskaya M, Morillon A. Histone H3 lysine 4 di-methylation: a novel mark for transcriptional fidelity? Epigenetics. 2009;4:302–306. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.5.9369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oesterreich S, Lee AV, Sullivan TM, Samuel SK, Davie JR, Fuqua SA. Novel nuclear matrix protein HET binds to and influences activity of the HSP27 promoter in human breast cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 1997;67:275–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Renz A, Fackelmayer FO. Purification and molecular cloning of the scaffold attachment factor B (SAF-B), a novel human nuclear protein that specifically binds to S/MAR-DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:843–849. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.5.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waltering KK, Helenius MA, Sahu B, Manni V, Linja MJ, Janne OA, et al. Increased expression of androgen receptor sensitizes prostate cancer cells to low levels of androgens. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8141–8149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oesterreich S. Scaffold attachment factors SAFB1 and SAFB2: Innocent bystanders or critical players in breast tumorigenesis? J Cell Biochem. 2003;90:653–661. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Townson SM, Dobrzycka KM, Lee AV, Air M, Deng W, Kang K, et al. SAFB2, a new scaffold attachment factor homolog and estrogen receptor corepressor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20059–20068. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao AC, Lou W, Ichikawa T, Denmeade SR, Barrett JC, Isaacs JT. Suppression of the tumorigenicity of prostatic cancer cells by gene(s) located on human chromosome 19p13.1-13. 2. The Prostate. 1999;38:46–54. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990101)38:1<46::aid-pros6>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiklund F, Gillanders EM, Albertus JA, Bergh A, Damber JE, Emanuelsson M, et al. Genome-wide scan of Swedish families with hereditary prostate cancer: suggestive evidence of linkage at 5q11.2 and 19p13. 3. The Prostate. 2003;57:290–297. doi: 10.1002/pros.10303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mukhopadhyay NK, Ferdinand AS, Mukhopadhyay L, Cinar B, Lutchman M, Richie JP, et al. Unraveling androgen receptor interactomes by an array-based method: discovery of proto-oncoprotein c-Rel as a negative regulator of androgen receptor. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:3782–3795. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim J, Ji M, DiDonato JA, Rackley RR, Kuang M, Sadhukhan PC, et al. An hTERT-immortalized human urothelial cell line that responds to anti-proliferative factor. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2011;47:2–9. doi: 10.1007/s11626-010-9350-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.