Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to investigate the changing pattern in the use of intravenous pyelogram (IVP), conventional computed tomography (CT), and non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography (NECT) for evaluation of patients with acute flank pain.

Materials and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 2,180 patients with acute flank pain who had visited Bundang Jesaeng General Hospital between January 2008 and December 2012 and analyzed the use of IVP, conventional CT, and NECT for these patients.

Results

During the study period there was a significant increase in NECT use (p<0.001) and a significant decrease in IVP use (p<0.001). Conventional CT use was also increased significantly (p=0.001). During this time the proportion of patients with acute flank pain who were diagnosed with urinary calculi did not change significantly (p=0.971).

Conclusions

There was a great shift in the use of imaging study from IVP to NECT between 2008 and 2012 for patients with acute flank pain.

Keywords: Flank pain, Non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography, Urinary calculi

INTRODUCTION

Acute flank pain is a common reason for patients to visit a urology clinic or emergency department and the intravenous pyelogram (IVP) has long been the imaging modality of choice in these patients. In evaluating flank pain, it is important to consider the accuracy, cost-effectiveness, safety, availability, and adaptability of the diagnostic modality. IVP has several advantages, including estimation of physiologic function, estimation of degree of obstruction, and detection of anatomical abnormalities of the urinary tract. However, IVP has some limitations, including difficulty in radiolucent calculi identification; contrast-related adverse reactions, such as nausea, vomiting, and anaphylaxis; and often a long and tedious study time to find the exact size and location of the calculi.

The application of non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography (NECT) for the evaluation of acute flank pain allows a rapid and accurate evaluation of the calculi in the urinary tract. After the pioneering prospective study on the role of NECT in the evaluation of acute flank pain by Smith et al. [1] in 1995, several studies reported that NECT is a safe, rapid, and highly sensitive imaging modality for evaluating acute flank pain compared with IVP or ultrasonography [2,3]. Its sensitivity was reported to be more than 95% and its specificity 98% [1-4]. In this study, we investigated the use of IVP, conventional computed tomography (CT), and NECT for evaluation of acute flank pain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records and radiologic study results of 2,243 patients with acute flank pain who visited the Urology Clinic or Emergency Department at Bundang Jesaeng General Hospital between January 2008 and December 2012. Of this group, 63 patients were excluded from the study owing to the absence of radiologic study and 2,180 patients were enrolled. A calculus was confirmed by spontaneous passage of the stone observed by the patients, surgical removal, or disappearance of the stone after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy.

IVP was taken in a standard fashion with 100 mL of nonionic contrast material. NECT was carried out by using a Brilliance 16 machine (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). The anatomic region between the upper margin of the T12 vertebrae and symphysis was scanned during a double-breath hold. Patients had a full bladder at the time of scanning. Scans were taken with 3-mm collimation on a pitch of 1.5. No oral or intravenous contrast medium was used.

All statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS ver. 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To analyze whether there was a change in the proportion of patients who underwent imaging study during the study period, we performed a test of trend using logistic regression analysis and used the chi-square test to determine the difference between proportions. Values of p<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant in all of the analyses.

RESULTS

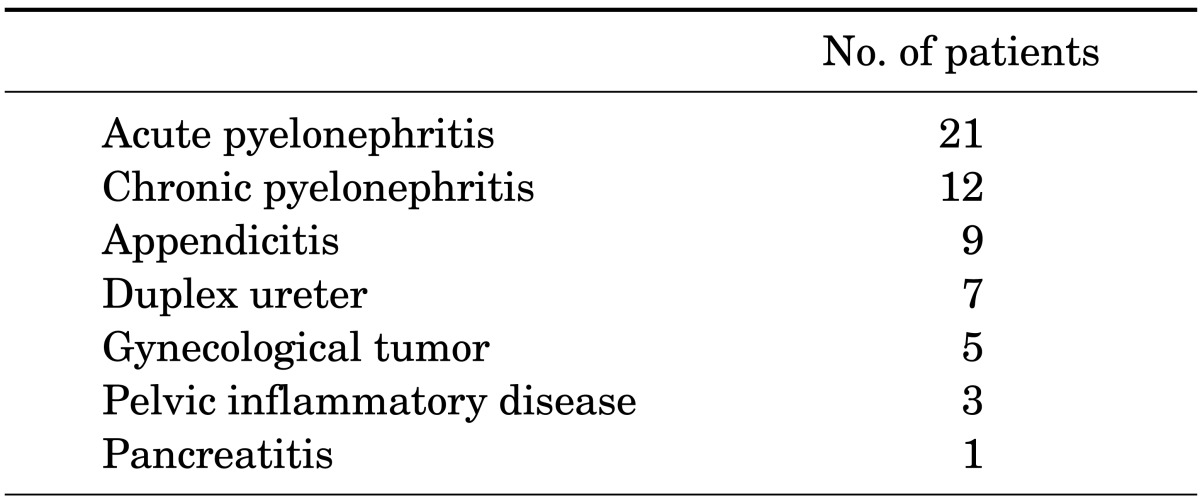

The mean age of the patients was 45.10±14.1 years, and 1,458 patients (66.9%) were men. Of the 380 patient visits evaluated in 2008, NECT was performed in 2 patients (0.5%). In 2012, a total of 542 visits were evaluated and 361 patients (66.6%) underwent NECT (Fig. 1). Among patients in whom radiologic study was performed for acute flank pain, 46.6% were diagnosed with a ureter stone in 2008 and 47.4% were diagnosed in 2012. The proportion of patients diagnosed with a ureter stone did not change significantly during the study period (p=0.971) (Table 1). The baseline characteristics of the urinary calculi are summarized in Table 2. Other causes for acute flank pain were acute pyelonephritis, chronic pyelonephritis, appendicitis, gynecological tumor, pelvic inflammatory disease, and pancreatitis (Table 3).

FIG. 1.

Trend change in imaging use for patients with acute flank pain. Diamond curve indicates intravenous pyelogram (IVP). Squares indicate non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography (NECT). Triangles indicate conventional computed tomography (CT). Multiplication sign indicates radiologic diagnosis (Dx).

TABLE 1.

Patients diagnosed with ureter stone during study period

p for trend=0.971.

TABLE 2.

Baseline characteristics of urinary calculi during study period

IVP, intravenous pyelogram; CT, computed tomography; NECT, non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography; SD, standard deviation.

TABLE 3.

Other cause for acute flank pain

NECT use increased significantly during the study (p<0.001), whereas there was a significant decrease in IVP use: 93.7% of patients underwent IVP in 2008 vs. 21.4% in 2012 (p<0.001). In addition, there was a significant rise in conventional CT use: 5.8% of patients underwent conventional CT in 2008 vs. 12.0% in 2012 (p=0.001).

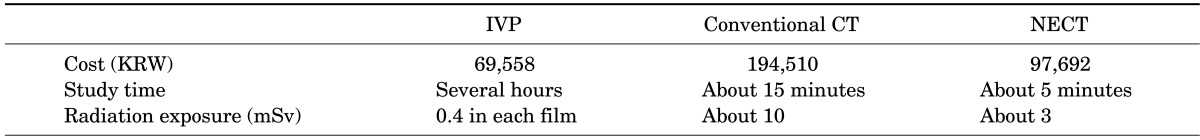

The cost, study time, and radiation exposure of IVP, conventional CT, and NECT are illustrated in Table 4. Whereas NECT showed a short study time, IVP indicated a lower radiation dose and better cost-effectiveness. IVP showed 81% sensitivity and 89% specificity. NECT had 96% sensitivity and 99% specificity. In case of conventional CT, its sensitivity and specificity were 98% and 100%, respectively.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of cost, study time and radiation exposure among imaging modalities

IVP, intravenous pyelogram; CT, computed tomography; NECT, non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography; KRW, Korean won; mSv, millisievert.

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that there was a significant increase in the use of NECT in patients with acute flank pain between 2008 and 2012. Several studies have also demonstrated an increasing use of CT for evaluation of acute flank pain [5,6]. In the past few years, NECT has been introduced for evaluating flank pain and it has proved to be an effective modality for the diagnosis of urinary calculi [7,8]. The reported sensitivity of NECT in evaluating patients with suspected urinary calculi was 97% to 98%, and its specificity was 96% to 100% [7-9]. NECT showed higher sensitivity and specificity than did IVP in this respect, because all urinary tract calculi could be identified by NECT. In addition, NECT could evaluate the severity of the urinary tract obstruction as well [10].

In this study, we investigated the use of alternative imaging modalities such as conventional CT or IVP and demonstrated that conventional CT use increased and IVP use decreased significantly during the study period. For each year between 2008 and 2012, fewer IVP procedures were ordered for patients with acute flank pain than were ordered the previous year. Although the number of conventional CT procedures increased significantly, we thought that this was meaningless because conventional CT was performed in only approximately 6% of cases in 2008 and 12% in 2012. In addition, the number of conventional CT procedures did not change that much after 2010.

NECT is a useful modality for several reasons. Compared with IVP, NECT has simple accessibility, rapid image acquisition time, advanced image quality, and no requirement for contrast material. Disuse of contrast material avoids the risk of contrast-induced adverse reactions, which occur in 1% to 10% of patients who undergo IVP [11]. The use of NECT may eliminate the costs of the contrast material. Furthermore, NECT is preferable to IVP in patients with acute flank pain associated with preexisting renal insufficiency because those patients have contraindications for IVP owing to the potential nephrotoxicity of the contrast material.

The accuracy of IVP is assumed to be high in diagnosing ureteral obstruction, but the exact accuracy is not known. Smith et al. [1] reported that urinary calculi as the cause of the obstruction might be undiagnosable with IVP in up to 58% of patients who had urographic findings of unilateral ureteral obstruction owing to small stone size, lack of ureteral opacification, or stone radiolucency. Moreover, extraurinary tract causes of acute flank pain usually could not be diagnosed with IVP. However, our study did not show a significant change in stone diagnosis, which remained stable at about 50%, despite the increasing NECT use and decreasing IVP use during the study. This result suggests that the increase in NECT use was not directly related with an increase in diagnosis of urinary calculi.

Potential disadvantages of NECT are cost and radiation exposure. Although financial charges vary among institutions, many institutions are charging less for CT scans performed without any contrast, and NECT is compatible compared with IVP. The actual charge for NECT in our institution is quoted to be 40% higher than the charge for IVP, but we believe that the higher price of NECT is offset by its increased accuracy, short study time, and usefulness in assessing extraurinary causes. Remer et al. [12] compared helical CT with combined plain radiography and ultrasonography in patients after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Their average time for CT scan was 15.3 minutes, compared with 37.2 minutes for combined plain radiographs and sonography. Their direct technical cost for helical CT was $36.86, compared with $57.60 for combined plain radiography and ultrasonography, as calculated by a cost-accounting system (Transition Systems, Boston, MA, USA). Those authors contended that the cost of CT equipment was four times as high as that for equipment for IVP, but the room time for CT was one-third that of IVP.

There is a concern of increased cancer risk resulting from the radiation exposure associated with medical imaging and CT [13,14]. Patients with urinary calculi are at increased risk for excessive radiation exposure owing to the recurrent nature of the disease and the resultant repetition of radiographic examinations [15,16]. Ferrandino et al. [17] reported that up to 20% of patients with renal stones exceeded the yearly dose safety limits for occupational exposure. As a result, low-dose CT protocols, which decrease the radiation exposure of the patients, have been developed.

Our study had several limitations. It was retrospective in nature and the size of the study population was smaller than a recently reported multicenter study because we collected our single-center experience with the disease. In addition, the data did not include information on treatment or clinical outcomes, which is helpful for understanding how diagnostic and treatment patterns might be related, and the follow-up period might not have been long enough. Also, the patients in this study underwent IVP, conventional CT, or NECT. A further study might be needed to investigate a sample in which all patients undergo both NECT and IVP studies to determine the accuracy of IVP in this population.

CONCLUSIONS

There was a significant increase in NECT use for the evaluation of acute flank pain between 2008 and 2012. The sensitivity of IVP, conventional CT, and NECT was 81%, 98%, and 96%, respectively. In addition, the specificity was 89%, 99%, and 100%, respectively. These results indicate that NECT is considered a good imaging modality for the evaluation of acute flank pain, although there was no significant change in the stone diagnosis proportion during the study duration. In addition, NECT can evaluate patients with an elevated creatinine level, adverse reactions to contrast material, and preexisting renal insufficiency. Therefore, NECT can be the evaluation of choice for detection of patients with urinary calculi. IVP can be used as a substitute for NECT when patients need several reexaminations because of its low radiation exposure compared with NECT.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Smith RC, Rosenfield AT, Choe KA, Essenmacher KR, Verga M, Glickman MG, et al. Acute flank pain: comparison of non-contrast-enhanced CT and intravenous urography. Radiology. 1995;194:789–794. doi: 10.1148/radiology.194.3.7862980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yilmaz S, Sindel T, Arslan G, Ozkaynak C, Karaali K, Kabaalioglu A, et al. Renal colic: comparison of spiral CT, US and IVU in the detection of ureteral calculi. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:212–217. doi: 10.1007/s003300050364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niall O, Russell J, MacGregor R, Duncan H, Mullins J. A comparison of noncontrast computerized tomography with excretory urography in the assessment of acute flank pain. J Urol. 1999;161:534–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spencer BA, Wood BJ, Dretler SP. Helical CT and ureteral colic. Urol Clin North Am. 2000;27:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70253-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyams ES, Korley FK, Pham JC, Matlaga BR. Trends in imaging use during the emergency department evaluation of flank pain. J Urol. 2011;186:2270–2274. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larson DB, Johnson LW, Schnell BM, Salisbury SR, Forman HP. National trends in CT use in the emergency department: 1995-2007. Radiology. 2011;258:164–173. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fielding JR, Steele G, Fox LA, Heller H, Loughlin KR. Spiral computerized tomography in the evaluation of acute flank pain: a replacement for excretory urography. J Urol. 1997;157:2071–2073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith RC, Verga M, McCarthy S, Rosenfield AT. Diagnosis of acute flank pain: value of unenhanced helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:97–101. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.1.8571915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad NA, Ather MH, Rees J. Unenhanced helical computed tomography in the evaluation of acute flank pain. Int J Urol. 2003;10:287–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2003.00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song HJ, Cho ST, Kim KK. Investigation of the location of the ureteral stone and diameter of the ureter in patients with renal colic. Korean J Urol. 2010;51:198–201. doi: 10.4111/kju.2010.51.3.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katzberg RW. Urography into the 21st century: new contrast media, renal handling, imaging characteristics, and nephrotoxicity. Radiology. 1997;204:297–312. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.2.9240511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Remer EM, Herts BR, Streem SB, Hesselink DP, Shiesly DA, Yost AJ, et al. Spiral noncontrast CT versus combined plain radiography and renal US after extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: cost-identification analysis. Radiology. 1997;204:33–37. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.1.9205219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography: an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2277–2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazel R, Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Ross JS, Chen J, Ting HH, et al. Exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:849–857. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz SI, Saluja S, Brink JA, Forman HP. Radiation dose associated with unenhanced CT for suspected renal colic: impact of repetitive studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:1120–1124. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sodickson A, Baeyens PF, Andriole KP, Prevedello LM, Nawfel RD, Hanson R, et al. Recurrent CT, cumulative radiation exposure, and associated radiation-induced cancer risks from CT of adults. Radiology. 2009;251:175–184. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511081296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferrandino MN, Bagrodia A, Pierre SA, Scales CD, Jr, Rampersaud E, Pearle MS, et al. Radiation exposure in the acute and short-term management of urolithiasis at 2 academic centers. J Urol. 2009;181:668–672. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]