Abstract

Activators of G protein signaling (AGS), initially discovered in the search for receptor-independent activators of G protein signaling, define a broad panel of biologic regulators that influence signal transfer from receptor to G-protein, guanine nucleotide binding and hydrolysis, G protein subunit interactions, and/or serve as alternative binding partners for Gα and Gβγ independently of the classic heterotrimeric Gαβγ. AGS proteins generally fall into three groups based upon their interaction with and regulation of G protein subunits: group I, guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEF); group II, guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors; and group III, entities that bind to Gβγ. Group I AGS proteins can engage all subclasses of G proteins, whereas group II AGS proteins primarily engage the Gi/Go/transducin family of G proteins. A fourth group of AGS proteins with selectivity for Gα16 may be defined by the Mitf-Tfe family of transcription factors. Groups I–III may act in concert, generating a core signaling triad analogous to the core triad for heterotrimeric G proteins (GEF + G proteins + effector). These two core triads may function independently of each other or actually cross-integrate for additional signal processing. AGS proteins have broad functional roles, and their discovery has advanced new concepts in signal processing, cell and tissue biology, receptor pharmacology, and system adaptation, providing unexpected platforms for therapeutic and diagnostic development.

Introduction

Since the initial discovery of the class of proteins defined as activators of G protein signaling (AGS) in 1999, concepts defining the biology of G proteins as signal transducers have evolved to embrace surprising mechanisms of regulation and diverse functional roles for the “G switch.” AGS and related entities may have evolved to provide a mechanism for cells to adapt in an acute and long-term manner to physiologic and pathologic challenges without altering the core components of a long-established signaling triad: receptor, G protein, and effector. During the course of evolving such adaptation or modulatory mechanisms, the component units (e.g., specific AGS proteins) may have been “hijacked” to also serve as core entities of signaling pathways that are not yet fully defined or may actually represent a window into a signaling system that is itself in the process of evolving. This mini-review touches upon the diverse functional roles of AGS proteins and expands upon recent concepts related to these proteins and signal processing.

Activators of G Protein Signaling: Mechanistic and Functional Diversity for the “G-Switch”

Activators of G protein signaling refer to a class of proteins initially defined in a yeast-based functional screen for mammalian cDNAs that activated G protein signaling in the absence of a G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) (Cismowski et al., 1999; Takesono et al., 1999). AGS proteins fall into three groups based upon their engagement with different G protein subunits and the biochemical consequences of this engagement with respect to Gα nucleotide exchange and/or subunit interactions. Serendipitously, these three groups were apparent with the discovery of the first three AGS proteins—AGS1, AGS2, and AGS3—each of which exhibited different mechanisms of action. This grouping then also captures other proteins with similar actions or functional domains. Sato et al. (2011) recently defined a fourth group of AGS proteins (AGS11–13) that activate G protein signaling in the yeast-based functional assay with Gα16, but not with yeast strains expressing Gpa1, Gαi2, or Gαi3. Although not as robust as the activation signal involving Gα16, AGS11–13 also activated G-protein signaling in yeast strains expressing Gαs (Sato et al., 2011). The AGS11–13 proteins actually encode three members of the Mitf-Tfe family of basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper transcription factors: transcription factor E3, microphthalmia-associated transcription factor, and transcription factor EB (Sato et al., 2011). The biochemical properties of the G protein regulation by AGS11–13 have not yet been fully characterized; however, TFE3 and Gα16 are both upregulated in the hypertrophic mouse heart, and TFE3 coexpression with Gα16 resulted in the nuclear localization of Gα16 and marked elevation of the mRNA encoding the tight junction protein claudin 14 (Sato et al., 2011).

Group I AGS Proteins.

Group I AGS proteins, which include AGS1 (Dexras1, RASD1); resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase (Ric)-8A and -8B; Gα-interacting, vesicle-associated protein (GIV)/Girdin/Akt-phosphorylation enhancer, act as nonreceptor guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) for Gα and/or Gαβγ (Cismowski et al., 1999, 2000; Tall et al., 2003; Tall and Gilman, 2005; Garcia-Marcos et al., 2009; Chan et al., 2011a, 2013; Tall, 2013). Ras homolog enriched in striatum (Rhes) or RASD2, which exhibits 66% amino acid similarity to AGS1, interacts with Gαi, and regulates G protein signaling, may be included in this group of AGS proteins, although it has not yet been shown to exhibit GEF activity in experiments with purified proteins (Falk et al., 1999; Vargiu et al., 2004; Thapliyal et al., 2008; Harrison and He, 2011). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein Arr4 also acts as a GEF for the yeast G protein GPA1 (Lee and Dohlman, 2008). Of particular interest, both GIV and Ric-8A act as GEFs for GαGDP when it is bound to group II AGS proteins (see below) containing G protein regulatory (GPR) motifs providing connectivity between group I and group II AGS proteins (Tall and Gilman, 2005; Thomas et al., 2008; Garcia-Marcos et al., 2011a).

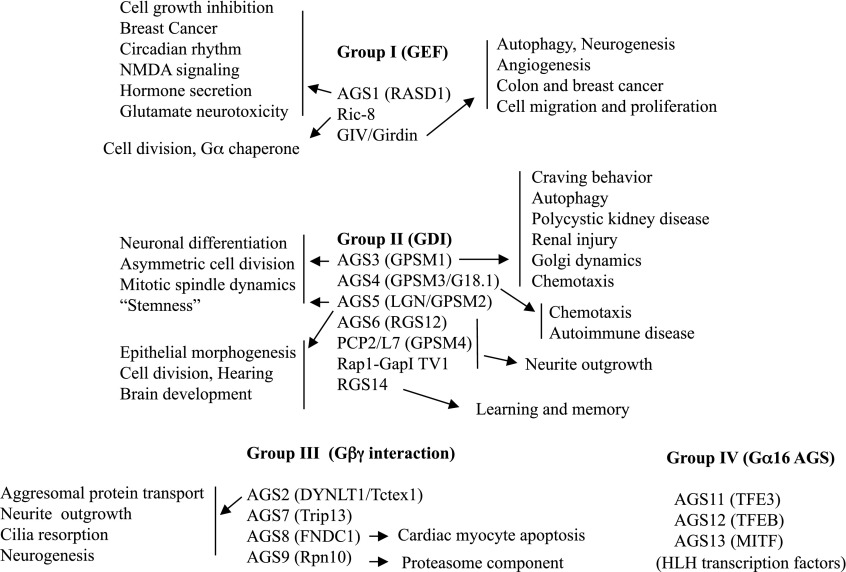

The group I AGS proteins exhibit selectivity in their interaction with G proteins: AGS1 (Gαi, Gαo, Gαi/oβγ) (Cismowski et al., 1999, 2000); Ric-8A (Gαi, Gαo, Gq, Gα13) (Tall et al., 2003; Tall and Gilman, 2005; Thomas et al., 2008; Chan et al., 2011a, 2013; Gabay et al., 2011); Ric-8B (Gαs, Gαolf) (Chan et al., 2011a,b); GIV/Girdin (Gαi, Gαs) (Le-Niculescu et al., 2005; Garcia-Marcos et al., 2009, 2010, 2011a; Ghosh et al., 2010; Beas et al., 2012); and Rhes (Gαi) (Harrison and He, 2011). The group I proteins have broad functional impact influencing tissue development, cell growth, and/or neuronal signaling (Fig. 1). Disruption of the Ric-8A gene, but not that of AGS1, Rhes, or GIV, is embryonic lethal (Cheng et al., 2004; Spano et al., 2004; Tonissoo et al., 2006; Kitamura et al., 2008; Enomoto et al., 2009; Tonissoo et al., 2010; Gabay et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2013).

Fig. 1.

Diversity of functional roles for AGS and related proteins.

AGS1 (RASD1, DexRas1) and Rhes (RASD2) are two related members of the Ras family of small G proteins (Kemppainen and Behrend, 1998; Falk et al., 1999). Both AGS1 and Rhes have an extended carboxyl terminus as compared with Ras family proteins, and both proteins interact with Gi/Go and regulate G protein signaling (Cismowski et al., 1999, 2000; Graham et al., 2002, 2004; Takesono et al., 2002; Vargiu et al., 2004; Nguyen and Watts, 2005; Harrison and He, 2011). AGS1 has a range of functional roles, including inhibition of cell growth, N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor signaling, regulation of the circadian rhythm, and regulation of hormone secretion (Fang et al., 2000; Graham et al., 2001; Jaffrey et al., 2002; Takahashi et al., 2003; Cheng et al., 2004; Vaidyanathan et al., 2004; Lellis-Santos et al., 2012; McGrath et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2013; Harrison et al., 2013). Rhes interacts with mutant huntingtin, influencing its cytotoxicity and the associated neurodegeneration in Huntington disease (Okamoto et al., 2009; Subramaniam et al., 2009; Baiamonte et al., 2013; Lu and Palacino, 2013; Mealer et al., 2013). Both AGS1 and Rhes increased the basal activity of N-type calcium channels via apparent activation of Gαiβγ, and both proteins antagonized the channel activation elicited by activation of a GPCR coupled to pertussis toxin–sensitive G proteins (Thapliyal et al., 2008). The inhibition of receptor-mediated events by AGS1 is similar to that observed for AGS1 in the regulation of potassium channels by M2-muscarinic receptors in Xenopus oocytes (Takesono et al., 2002). AGS1 and/or Rhes also influence the regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and adenylyl cyclase by heterotrimeric G proteins (Cismowski et al., 2000; Graham et al., 2001, 2002, 2004; Nguyen and Watts, 2005; Harrison and He, 2011). Both proteins bind to Gα (Cismowski et al., 1999, 2000; Harrison and He, 2011) and perhaps Gβγ (Hiskens et al., 2005; Hill et al., 2009). The mechanistic aspects of AGS1- and Rhes-mediated effects on heterotrimeric G protein signaling systems are not fully understood. It is likely that there are actions of AGS1 and Rhes that are G protein independent.

Ric-8A acts as a chaperone for Gαi, regulating Gα folding and processing during its biosynthesis; this regulatory action requires its GEF activity (Gabay et al., 2011; Chan et al., 2013). The interaction of Ric-8A with Gα stabilizes the G protein subunit, and in its absence Gα levels are markedly reduced. Ric-8A may also play a role in signal processing independent of its chaperone function. The Ric-8A–GαGPR pathway regulates asymmetrical cell division and mitotic spindle orientation in model organisms and mammalian cells (Afshar et al., 2004; Couwenbergs et al., 2004; David et al., 2005; Hampoelz et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005; Woodard et al., 2010). As is also the case for GPCR coupling to Gαβγ, the action of Ric-8A on the GαGPR signaling module is blocked by cell treatment with pertussis toxin (Woodard et al., 2010; Oner et al., 2013a). It is not clear what lies downstream of the Ric-8A–GαGPR module, and it is not clear what provides signal input to the module.

GIV/Girdin/Akt-phosphorylation enhancer was first identified as an Akt substrate and a Gα-interacting protein by yeast two hybrid screens (Anai et al., 2005; Enomoto et al., 2005; Le-Niculescu et al., 2005). GIV is involved in signals from the epidermal growth factor receptor, the insulin receptor, and GPCRs that regulate cell migration, proliferation, and autophagy (Anai et al., 2005; Enomoto et al., 2005; Garcia-Marcos et al., 2009, 2010, 2011a; Ghosh et al., 2010). Elevated levels of GIV are associated with increased incidence of colon and breast cancer metastasis (Garcia-Marcos et al., 2011b; Liu et al., 2012). The regulation of autophagy by several cell-surface receptors apparently requires the GEF activity of GIV acting upon a GαGPR complex at autophagic vesicles (Garcia-Marcos et al., 2011a). GIV also integrates signals processed through heterotrimeric G proteins subsequent to GPCR activation by acting as a putative rheostat to provide graded signal integration across different pathways (Ghosh et al., 2011). GIV/Girdin knockout mice exhibit defects in angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and cell motility (Enomoto et al., 2005; Kitamura et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). The action of GIV on cell motility may relate in part to its ability to interact with the partitioning defective (PAR) protein complex (Ohara et al., 2012). GIV is also localized to the centrosome and the midbody as observed for AGS5 (Blumer et al., 2006; Mao et al., 2012). Interestingly, group II AGS proteins AGS5/LGN and AGS3 are also able to interact with and influence the subcellular distribution of the PAR complex to regulate cell polarity and in some cases orient the mitotic spindle (Lechler and Fuchs, 2005; Zigman et al., 2005; Izaki et al., 2006; Yuzawa et al., 2011; Kamakura et al., 2013;). As Gαi-AGS3 is a substrate for the GEF activity of GIV (Garcia-Marcos et al., 2011a), this may illustrate yet another area of possible connectivity between group I and group II AGS proteins. Finally, as with AGS1 and Rhes, it is not clear if all of the actions of GIV/Girdin involve the regulation of Gαβγ and/or GαGPR.

Group II AGS Proteins.

Mammalian group II AGS proteins consist of seven proteins: AGS3 (G protein signaling modulator [GPSM] 1), LGN (GPSM2, AGS5), AGS4 (GPSM3), regulator of G protein signaling (RGS)12 (AGS6), Rap1Gap (Transcript Variant 1), RGS14, and PCP2/L7 (GPSM4), each of which contains one to four GPR motifs for docking of Gα, serving as alternative binding partners for specific subtypes of Gα. Group II AGS proteins engage the Gi/Go/transducin family of G proteins. The three types of mammalian group II AGS proteins are distinguished by the number of GPR motifs and/or the presence of defined regulatory protein domains (Sato et al., 2006a; Blumer et al., 2007, 2012). AGS3 and LGN (AGS5) have four GPR motifs downstream of a tetratricopeptide repeat domain, whereas RGS12 (AGS6), RGS14, and Rap1GAP have one GPR motif plus other defined domains that act to accelerate Gα−GTP hydrolysis. AGS3-SHORT, AGS4 (GPSM3), and PCP2/L7 (GPSM4) have multiple GPR motifs without any other clearly defined regulatory protein domains.

The GPR motif stabilizes the Gα subunit in its GDP-bound conformation and inhibits GTPγS binding (see references in Willard et al., 2004; Sato et al., 2006a), and thus group II proteins behave as guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors in a manner analogous to Gβγ. Group II AGS proteins with multiple GPR motifs can bind a corresponding number of Gα proteins. Thus, for AGS3 and AGS5, up to four Gα proteins may be docked to the GPR protein at any given moment. The structural organization and intramolecular dynamics of such a complex is of interest. Different members of the Gαi/o family may be docked to the protein and there may be cooperativity among the multiple GPR motifs with respect to their interaction with Gα. Different GPR motifs may exhibit Gα selectivity within the family of pertussis toxin–sensitive G proteins (Mittal and Linder, 2004). AGS4, which has three GPR motifs, is also reported to interact with Gβγ, and its amino terminal region exhibits apparent GEF activity (Zhao et al., 2010; Giguère et al., 2012). Selected GPR motifs in D. melanogaster and C. elegans AGS3 orthologs are reported to also engage GαGTP (Kopein and Katanaev, 2009; Yoshiura et al., 2012), although it is not clear how these data are reconciled with the large majority of information indicating that GPR motifs stabilize the GDP-bound conformation of Gα. The X-ray crystal structures of AGS5/LGN in complex with binding partners NuMA, mInsc, and Frmpd1 were recently determined, as were the complexes of AGS5/LGN and RGS14 GPR domains with GαiGDP (Kimple et al., 2002; Culurgioni et al., 2011; Yuzawa et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2011; Jia et al., 2012; Pan et al., 2013).

The GαGPR complex participates in an increasingly fascinating set of regulatory functions that we are just beginning to understand (Fig. 1). In mammalian systems, AGS3 is implicated in asymmetric cell division, neuronal plasticity and addiction, autophagy, membrane protein trafficking, polycystic kidney disease, renal response to ischemia, immune cell chemotaxis, insulin-like growth factor-1 mediated ciliary resorption, cardiovascular regulation, and metabolism (Blumer et al., 2002, 2006, 2008; Blumer and Lanier, 2003; Ghosh et al., 2003; Gotta et al., 2003; Pattingre et al., 2003; Bowers et al., 2004, 2008; Sato et al., 2004; Yao et al., 2005, 2006; Groves et al., 2007; Willard et al., 2008; Groves et al., 2010; Nadella et al., 2010; Vural et al., 2010; Hofler and Koelle, 2011; Regner et al., 2011; Chauhan et al., 2012; Kwon et al., 2012; Conley and Watts, 2013; Kamakura et al., 2013; Yeh et al., 2013). AGS3 single nucleotide polymorphisms are associated with diabetes and glucose handling (Scott et al., 2012; Hara et al., 2014; Huyghe et al., 2013). AGS4 (GPSM3), which is enriched in immune cells and regulates immune cell chemotaxis, is associated with autoimmune diseases (Cao et al., 2004; Giguere et al., 2013). AGS5, which exhibits a similar domain structure as AGS3, also plays important functional roles in asymmetric cell division and morphogenesis, and was recently identified as a responsible gene for certain types of nonsyndromic hearing loss, planar cell polarity in cochlear hair cells, and the brain malformations and hearing loss observed as part of the Chudley-McCullough syndrome (Du et al., 2001; Du and Macara, 2004; Lechler and Fuchs, 2005; Fukukawa et al., 2010; Walsh et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2010, 2013; Williams et al., 2011; Yariz et al., 2012; Diaz-Horta et al., 2012; Doherty et al., 2012; Almomani et al., 2013; Ezan et al., 2013). The functional role of AGS5 and G proteins in coordinating planar cell polarity of the cochlear hair cell may involve both the PAR polarity protein complex and positioning of the kinocilium (Ezan et al., 2013). Both AGS5 and AGS3 also interact with guanylate cyclase, and AGS5 appears to regulate guanylate cyclase activity (Chauhan et al., 2012).

The functional role of AGS3 in the kidney is of particular interest. AGS3 is expressed at low or undetectable levels in the normal kidney, but when the organ is challenged by ischemia or polycystic kidney disease, AGS3 expression is markedly upregulated (Nadella et al., 2010; Regner et al., 2011; Kwon et al., 2012). The upregulation of AGS3 may serve as a “protective adaptation” by facilitating epithelial cell repair in both types of organ stress. The loss of AGS3 delays the recovery from the ischemic challenge and results in a dramatic increase in cyst formation in animal models of polycystic kidney disease. Mechanistically, this action of AGS3 may be mediated through Gβγ, which may regulate the polycystins PC1/PC2 (Kwon et al., 2012). These data provide another example of an action of AGS3 on G protein subunit interactions that augments Gβγ-mediated signaling (Takesono et al., 1999; Sato et al., 2004; Sanada and Tsai, 2005; Nadella et al., 2010; Regner et al., 2011; Kwon et al., 2012).

The number of GPR proteins has expanded with evolution. D. melanogaster has one GPR protein (partner of inscuteable) that has a domain structure similar to mammalian AGS3 and AGS5 and plays an important functional role in asymmetric cell division and cell polarity (Parmentier et al., 2000; Schaefer et al., 2000, 2001; Yu et al., 2000; Nipper et al., 2007; Cabernard et al., 2010; Yoshiura et al., 2012; Bergstralh et al., 2013). C. elegans has two GPR proteins, one of which is similar to AGS3 and AGS5 and may integrate neural signals required for system adaptation (Hofler and Koelle, 2011). A second C. elegans GPR protein, GPR1/2, is required for asymmetric cell division during early development (Colombo et al., 2003; Gotta et al., 2003; Srinivasan et al., 2003). In both model organisms, the functional roles of the GPR proteins involve the regulation of Gα signaling.

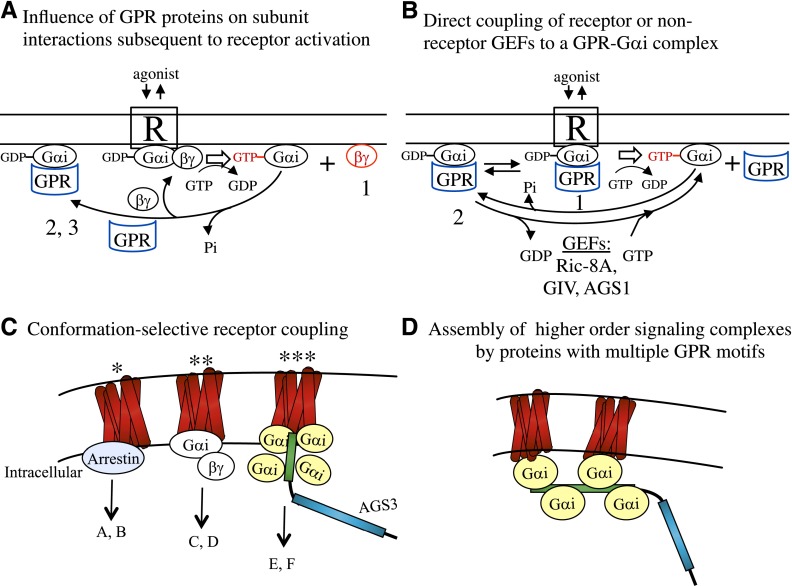

The expansion of the GPR family with evolution reflects important roles in complex biologic events. The mechanism by which the GPR protein AGS3 influences a range of cell and tissue behaviors is not clear. The protein may influence specific signaling events through heterotrimeric G proteins (Fig. 2A), function as part of a distinct signaling pathway (e.g., GαGPR signaling module) (Fig. 2B), serve as a chaperone for Gα, and/or impact basic cellular events such as autophagy (Pattingre et al., 2003; Groves et al., 2010; Vural et al., 2010; Garcia-Marcos et al., 2011a) and secretory pathway dynamics (Groves et al., 2007; Oner et al., 2013b).

Fig. 2.

Schematic illustrations of the influence of group I and II AGS proteins on G protein signal processing and signal integration. (A) Influence of GPR proteins (group II AGS proteins) on subunit interactions subsequent to receptor activation. In this scenario, agonist-bound receptor catalyzes nucleotide exchange on Gαi/oβγ and releases Gβγ for effector engagement. Upon GTP hydrolysis (either by intrinsic GTPase activity or accelerated by regulators of G protein signaling), the GαiGDP may reassociate with Gβγ. As GPR motifs compete with Gβγ for GαiGDP binding (Bernard et al., 2001; Ghosh et al., 2003; Oner et al., 2010a,b), GPR proteins may actually bind GαiGDP prior to its reassociation with Gβγ during receptor-mediated G protein cycling. GαGDPGPR complexes formed in this context may: 1) enhance or prolong Gβγ-mediated effector activation, 2) serve as targets for nonreceptor GEFs (group I AGS proteins), and/or 3) initiate the formation of a larger signaling complex whose action is distinct from Gβγ-mediated signaling. (B) Working hypotheses for GαGPR complexes as direct targets for receptor (1) or nonreceptor (2) GEFs. In this scenario, the GPR protein serves a role analogous to that of Gβγ in the heterotrimer Gαβγ. GEF action on this GαGPR complex is depicted at the plasma membrane, but could also ostensibly occur at other subcellular compartments. As in A, the GαGPR complex can initiate the formation of noncanonical signaling complexes (e.g., those involved in the regulation of mitotic spindle dynamics and cell polarity). (C) Conformation-selective receptor coupling to different candidate signal transducers. Receptor coupling to these three distinct transducer elements is hypothesized to regulate different signaling pathways (depicted as “A–F”) and/or differentially regulate the strength and duration of generated signals. The direct coupling of a G protein–coupled receptor to GαGPR is presented as a hypothesis to be tested. The hypothesis is based upon the following: 1) the ability of both the GPR motif and Gβγ to stabilize Gα in the GDP-bound conformation, 2) the regulation of AGS3-Rluc-Gαi-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) and AGS4-Rluc-Gαi-YFP by a cell-surface G protein–coupled receptor as determined by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) (Oner et al., 2010a,b), and 3) the Gαi-dependent BRET between a cell-surface G protein–coupled receptor tagged with Venus and AGS3-, AGS4-, and RGS14-Rluc (Oner et al., 2010a,b; Vellano et al., 2011, 2013). (D) Hypothetical assembly of higher-order signaling complexes by proteins with multiple GPR motifs. AGS3, which contains four GPR motifs, is used as an example of a multi–GPR-motif protein that may provide multiple GαGPR docking sites for a GPCR.

Group III AGS Proteins.

Group III AGS proteins interact with Gβγ or perhaps Gαβγ (Cismowski et al., 1999; Sato et al., 2006b, 2009; Yuan et al., 2007). The group III AGS proteins are a diverse group, and their roles in G protein signaling systems are not well defined. In general, the group III proteins interact with Gβγ and exhibit nonselectivity for Gα subunits in the yeast-based functional screen. It was hypothesized that group III AGS proteins influence subunit (Gα and Gβγ) interactions independent of nucleotide exchange via an interaction with Gαβγ or Gβγ leading to dissociation of Gαβγ, resulting in increased “free” Gβγ for effector engagement in the yeast-based functional screen. Many of the group III AGS proteins play important functional roles in different systems (Fig. 1). AGS8 was actually identified as part of a strategy to identify disease- or challenge-specific AGS proteins in different model systems (Sato et al., 2006b). AGS8, which is upregulated in a rat model of cardiac hypertrophy, is required for hypoxia-induced apoptosis of cardiomyocytes, although the mechanism involved is not fully defined (Sato et al., 2009). AGS2/Tctex1/DYNLT1 is a component of the cytoplasmic motor protein dynein and actually functions in one capacity as a Gβγ effector regulating neurite outgrowth and neurogenesis (Sachdev et al., 2007; Gauthier-Fisher et al., 2009; Yeh et al., 2013).

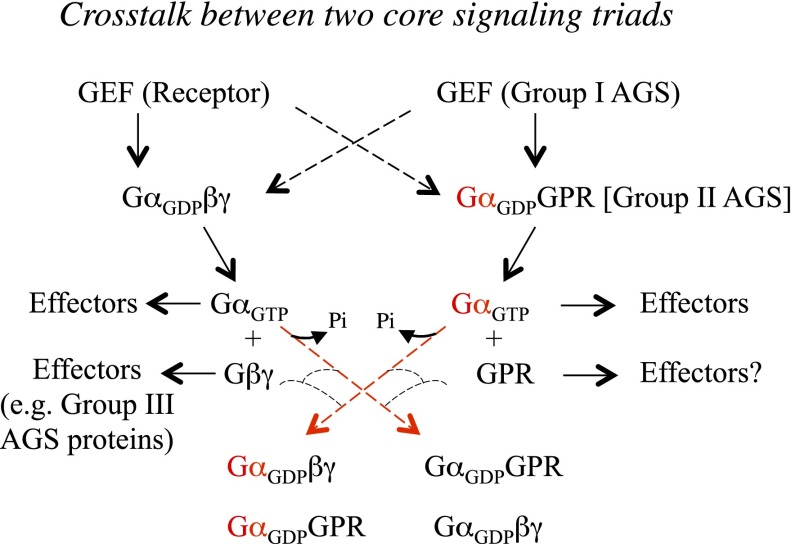

Two Core Signaling Triads

The observation that AGS proteins fell into three distinct functional groups, when initially discovered, may have greater significance than first appreciated. The three defined groups revealed unexpected regulatory mechanisms for G proteins, actually suggesting a previously undefined path for signal processing. The three functional groups of AGS proteins are GEFs (nonreceptor, group I), GαGPR (GPR as a guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor, group II), and proteins interacting with Gβγ (group III), which is analogous to the core signaling triad for heterotrimeric G proteins: GEFs (receptor), Gαβγ (Gβγ as a guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor) and effector (e.g., Gβγ binding proteins) (Figs. 2 and 3). Thus, one might imagine that there may be opportunities for the three groups of AGS proteins to align their different functional mechanisms and act in concert to regulate biologic events. Extending this thought, one may also imagine communication between the two core signaling triads. Such cross-talk may be sequential or coordinated as a cycle and may occur at different points across the two triads (Figs. 2, A and B, and 3).

Fig. 3.

Cross-talk between two core signaling triads. This schematic presents a working model for AGS proteins as a core signaling triad and for potential cross-talk between the core signaling triads involving G proteins. The direct coupling of a G protein–coupled receptor to GαGPR is presented as a hypothesis to be tested. The schematic representation of a GPR protein interacting with an effector and the presentation of Gα exchange (red lines) between Gαβγ and GαGPR subsequent to GEF activation are speculative.

Certainly the regulation of the GαGPR complex by Ric-8A and GIV is an example of cross-talk among groups I and II AGS proteins. Cross-talk may also occur across the two core signaling triads. Group I AGS proteins may regulate Gα and/or Gαβγ (Fig. 3). Another example of cross-talk between the two core signaling triads is illustrated in Fig. 2A. The GαGPR complex generated subsequent to receptor activation of Gαβγ may impede the reassociation of Gα and Gβγ augmenting Gβγ-mediated signaling events (Fig. 2A). In addition, the newly generated Gα-GPR may initiate the formation of a signaling complex that acts independently of Gβγ-mediated signaling. For example, during neutrophil chemotaxis the GαiAGS3 complex acts as a docking site for polarized formation of a mInsc-Par3-Par6-aPKC complex, which is important for efficient chemokine-directed migration (Kamakura et al., 2013). Such a GαGPR complex could also serve as a target for group I AGS proteins, as suggested for signaling events associated with feeding behavior in C. elegans (Hofler and Koelle, 2011). Such signaling events may be cyclic and could result in the generation of different combinations of Gα and Gβγ by subunit exchange (Fig. 3).

Group II and III AGS proteins may also work together, providing another platform for system cross-talk. In neuronal stem cells, the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor couples to heterotrimeric G proteins. Subsequent to dissociation of Gα and Gβγ, the group II protein AGS3 interacts with Gα-GDP, allowing Gβγ to engage the dynein light chain AGS2 (group III AGS protein) as an effector to regulate cilia resorption and cell differentiation (Yeh et al., 2013). There may be additional points of “cross-talk” involving AGS2. Dynein also regulates the movement of proteins through the aggresome pathway and the regulation of spindle pulling forces during cell division. The GPR protein AGS3 actually traffics into the aggresome pathway, and the GPR proteins AGS3 and AGS5, together with Gα, also regulate spindle orientation and spindle dynamics during asymmetric cell division. The group I AGS protein Ric-8A also regulates asymmetric cell division (Afshar et al., 2004; Hess et al., 2004; Hampoelz et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005).

Although the majority of Gα within the cell likely exists as part of the Gαβγ heterotrimer at the plasma membrane, a subpopulation of Gα is apparently complexed with GPR proteins (Fig. 2B) (Schaefer et al., 2000; Bernard et al., 2001; Blumer et al., 2003; Afshar et al., 2004; Nair et al., 2005; Wiser et al., 2006; Garcia-Marcos et al., 2011a). The GαGPR complex may be generated by direct action of a GPR protein on Gαβγ independent of receptor activation or subsequent to dissociation of Gαβγ in response to receptor activation as noted above. Alternatively, Gα and GPR may associate with each other during their biosynthesis or via colocalization in microdomains of the cell independent of any engagement with Gαβγ.

Both the GPR motif and Gβγ stabilize Gα in its GDP-bound conformation, which is the conformation of Gα when initially engaged by a GPCR. Thus, the hypothesis that a GPCR couples directly to the GαGPR complex presents another path for cross-talk between the two core signaling triads (Figs. 2B and 3). Although it is generally accepted that Gβγ plays a role in receptor recognition of Gαβγ, the X-ray crystal structure of the β2-adrenergic receptor (AR)-Gsαβγ complex indicates no direct contacts of the receptor with Gβγ (Rasmussen et al., 2011). These data do not rule out an interaction of β2-AR with the Gβγ subunits as the β2-AR-Gαβγ complex is “stabilized,” but they also do not rule out a primary interaction of the receptor with Gα—an interaction that might be mimicked in the context of a GαGPR complex (see Discussion in Oner et al., 2010a).

A series of studies involving bioluminescence resonance energy transfer in transfected cell models indicates that GαGPR complexes (Gαi-AGS3, Gαi-AGS4, Gαi-RGS14) at the plasma membrane are indeed regulated by a subgroup of G protein–coupled receptors, presenting an unexpected mechanism for signal input to GαGPR complex (Oner et al., 2010a,b, 2013a; Vellano et al., 2011, 2013) (Fig. 2B). Activation of the α2-AR leads to dissociation of the GαAGS3 and the GαAGS4 complex and release of the GPR protein from the inner face of the plasma membrane (Oner et al., 2010a,b, 2013b). Both transfected and endogenous AGS3 translocate to the Golgi apparatus subsequent to dissociation from Gα (Oner et al., 2013b).

It is not known if the regulation of the GαGPR complex by a G protein–coupled receptor reflects direct coupling of the receptor to the GαGPR complex or involves cycling of G protein subunits subsequent to GPCR activation of Gαβγ within a larger signaling complex. An extension of this hypothesis regarding direct coupling of a GPCR to GαGPR is that a GPCR may couple to GαGPR in a ligand-dependent, conformationally-selective manner analogous to ligand-bias as described for GPCR coupling to Gαβγ and β-arrestin, offering substantial flexibility for systems to adapt and respond to extracellular stimuli (Fig. 2C) (Brink et al., 2000; Gesty-Palmer and Luttrell, 2011; Blattermann et al., 2012; Kenakin, 2012; Pradhan et al., 2012; Reiter et al., 2012; Rivero et al., 2012; Ahn et al., 2013; DeWire et al., 2013; Katritch et al., 2013; Kelly, 2013; Kenakin and Christopoulos, 2013; Wehbi et al., 2013; Wootten et al., 2013). One might imagine that receptor coupling to these three distinct transducer elements would regulate different signaling pathways and/or the strength and duration of generated signals and offer additional opportunities to expand upon the concept of pathway targeted drugs. Proteins with multiple GPR motifs may assemble Gαi units within a larger scaffold with receptor (Fig. 2D), providing additional interesting mechanisms for sensing receptor activation and influencing signaling kinetics and specificity in ways not yet fully appreciated.

Perspective.

The discovery of the family of AGS proteins and related accessory proteins revealed totally unexpected mechanisms for regulation of the G protein activation cycle and has opened up new areas of research related to the cellular role of G proteins as signal transducers with broad functional impact. Key questions going forward include the following.

How is the biochemistry of AGS proteins translated into function?

What regulates the interaction of AGS proteins with G proteins?

Do cell surface receptors couple directly to a GαGPR complex?

Is the core signaling triad defined by AGS proteins a therapeutic target?

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the continuous input provided to this effort over the years by the many fellows and students that have spent time in their laboratories and the valuable input of many colleagues, in particular, Professor K. U. Malik. The authors also acknowledge the support provided by the David R. Bethune/Lederle Laboratories Professorship in Pharmacology at LSU Health Sciences Center–New Orleans (to S.M.L.) and the Research Scholar Award from Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Company (Astellas Pharma) (to S.M.L.).

Abbreviations

- AGS

activators of G protein signaling

- AR

adrenergic receptor

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- GIV

Gα-interacting, vesicle-associated protein

- GPCR

G protein–coupled receptor

- GPR

G protein regulatory

- GPSM

G protein signaling modulator

- PAR

partitioning defective

- RGS

regulator of G protein signaling

- Rhes

Ras homolog enriched in striatum

- Ric

resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase

Authorship Contributions

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Blumer, Lanier.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Grants R01-GM086510 and R01-GM074247]; the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Grant R01-NS24821]; the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grant R01-DA025896]; and the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Mental Health [Grant R01-MH59931].

References

- Afshar K, Willard FS, Colombo K, Johnston CA, McCudden CR, Siderovski DP, Gönczy P. (2004) RIC-8 is required for GPR-1/2-dependent Galpha function during asymmetric division of C. elegans embryos. Cell 119:219–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn KH, Mahmoud MM, Shim JY, Kendall DA. (2013) Distinct roles of β-arrestin 1 and β-arrestin 2 in ORG27569-induced biased signaling and internalization of the cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1). J Biol Chem 288:9790–9800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almomani R, Sun Y, Aten E, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, Peeters-Scholte CM, van Haeringen A, Hendriks YM, den Dunnen JT, Breuning MH, Kriek M, et al. (2013) GPSM2 and Chudley-McCullough syndrome: a Dutch founder variant brought to North America. Am J Med Genet A 161A:973–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anai M, Shojima N, Katagiri H, Ogihara T, Sakoda H, Onishi Y, Ono H, Fujishiro M, Fukushima Y, Horike N, et al. (2005) A novel protein kinase B (PKB)/AKT-binding protein enhances PKB kinase activity and regulates DNA synthesis. J Biol Chem 280:18525–18535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baiamonte BA, Lee FA, Brewer ST, Spano D, LaHoste GJ. (2013) Attenuation of Rhes activity significantly delays the appearance of behavioral symptoms in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. PLoS ONE 8:e53606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beas AO, Taupin V, Teodorof C, Nguyen LT, Garcia-Marcos M, Farquhar MG. (2012) Gαs promotes EEA1 endosome maturation and shuts down proliferative signaling through interaction with GIV (Girdin). Mol Biol Cell 23:4623–4634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstralh DT, Lovegrove HE, St Johnston D. (2013) Discs large links spindle orientation to apical-basal polarity in Drosophila epithelia. Curr Biol 23:1707–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard ML, Peterson YK, Chung P, Jourdan J, Lanier SM. (2001) Selective interaction of AGS3 with G-proteins and the influence of AGS3 on the activation state of G-proteins. J Biol Chem 276:1585–1593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blättermann S, Peters L, Ottersbach PA, Bock A, Konya V, Weaver CD, Gonzalez A, Schröder R, Tyagi R, Luschnig P, et al. (2012) A biased ligand for OXE-R uncouples Gα and Gβγ signaling within a heterotrimer. Nat Chem Biol 8:631–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer JB, Bernard ML, Peterson YK, Nezu J, Chung P, Dunican DJ, Knoblich JA, Lanier SM. (2003) Interaction of activator of G-protein signaling 3 (AGS3) with LKB1, a serine/threonine kinase involved in cell polarity and cell cycle progression: phosphorylation of the G-protein regulatory (GPR) motif as a regulatory mechanism for the interaction of GPR motifs with Gi alpha. J Biol Chem 278:23217–23220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer JB, Chandler LJ, Lanier SM. (2002) Expression analysis and subcellular distribution of the two G-protein regulators AGS3 and LGN indicate distinct functionality. Localization of LGN to the midbody during cytokinesis. J Biol Chem 277:15897–15903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer JB, Kuriyama R, Gettys TW, Lanier SM. (2006) The G-protein regulatory (GPR) motif-containing Leu-Gly-Asn-enriched protein (LGN) and Gialpha3 influence cortical positioning of the mitotic spindle poles at metaphase in symmetrically dividing mammalian cells. Eur J Cell Biol 85:1233–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer JB, Lanier SM. (2003) Accessory proteins for G protein-signaling systems: activators of G protein signaling and other nonreceptor proteins influencing the activation state of G proteins. Receptors Channels 9:195–204 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer JB, Lord K, Saunders TL, Pacchioni A, Black C, Lazartigues E, Varner KJ, Gettys TW, Lanier SM. (2008) Activator of G protein signaling 3 null mice: I. Unexpected alterations in metabolic and cardiovascular function. Endocrinology 149:3842–3849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer JB, Oner SS, Lanier SM. (2012) Group II activators of G-protein signalling and proteins containing a G-protein regulatory motif. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 204:202–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumer JB, Smrcka AV, Lanier SM. (2007) Mechanistic pathways and biological roles for receptor-independent activators of G-protein signaling. Pharmacol Ther 113:488–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers MS, Hopf FW, Chou JK, Guillory AM, Chang SJ, Janak PH, Bonci A, Diamond I. (2008) Nucleus accumbens AGS3 expression drives ethanol seeking through G betagamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:12533–12538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers MS, McFarland K, Lake RW, Peterson YK, Lapish CC, Gregory ML, Lanier SM, Kalivas PW. (2004) Activator of G protein signaling 3: a gatekeeper of cocaine sensitization and drug seeking. Neuron 42:269–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brink CB, Wade SM, Neubig RR. (2000) Agonist-directed trafficking of porcine alpha(2A)-adrenergic receptor signaling in Chinese hamster ovary cells: l-isoproterenol selectively activates G(s). J Pharmacol Exp Ther 294:539–547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabernard C, Prehoda KE, Doe CQ. (2010) A spindle-independent cleavage furrow positioning pathway. Nature 467:91–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Cismowski MJ, Sato M, Blumer JB, Lanier SM. (2004) Identification and characterization of AGS4: a protein containing three G-protein regulatory motifs that regulate the activation state of Gialpha. J Biol Chem 279:27567–27574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P, Gabay M, Wright FA, Kan W, Oner SS, Lanier SM, Smrcka AV, Blumer JB, Tall GG. (2011a) Purification of heterotrimeric G protein alpha subunits by GST-Ric-8 association: primary characterization of purified G alpha(olf). J Biol Chem 286:2625–2635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P, Gabay M, Wright FA, Tall GG. (2011b) Ric-8B is a GTP-dependent G protein alphas guanine nucleotide exchange factor. J Biol Chem 286:19932–19942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan P, Thomas CJ, Sprang SR, Tall GG. (2013) Molecular chaperoning function of Ric-8 is to fold nascent heterotrimeric G protein α subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:3794–3799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan S, Jelen F, Sharina I, Martin E. (2012) The G-protein regulator LGN modulates the activity of the NO receptor soluble guanylate cyclase. Biochem J 446:445–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Khan RS, Cwanger A, Song Y, Steenstra C, Bang S, Cheah JH, Dunaief J, Shindler KS, Snyder SH, et al. (2013) Dexras1, a small GTPase, is required for glutamate-NMDA neurotoxicity. J Neurosci 33:3582–3587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HY, Obrietan K, Cain SW, Lee BY, Agostino PV, Joza NA, Harrington ME, Ralph MR, Penninger JM. (2004) Dexras1 potentiates photic and suppresses nonphotic responses of the circadian clock. Neuron 43:715–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cismowski MJ, Ma C, Ribas C, Xie X, Spruyt M, Lizano JS, Lanier SM, Duzic E. (2000) Activation of heterotrimeric G-protein signaling by a ras-related protein. Implications for signal integration. J Biol Chem 275:23421–23424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cismowski MJ, Takesono A, Ma C, Lizano JS, Xie X, Fuernkranz H, Lanier SM, Duzic E. (1999) Genetic screens in yeast to identify mammalian nonreceptor modulators of G-protein signaling. Nat Biotechnol 17:878–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo K, Grill SW, Kimple RJ, Willard FS, Siderovski DP, Gönczy P. (2003) Translation of polarity cues into asymmetric spindle positioning in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Science 300:1957–1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley JM, Watts VJ. (2013) Differential effects of AGS3 expression on D(2L) dopamine receptor-mediated adenylyl cyclase signaling. Cell Mol Neurobiol 33:551–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couwenbergs C, Spilker AC, Gotta M. (2004) Control of embryonic spindle positioning and Galpha activity by C. elegans RIC-8. Curr Biol 14:1871–1876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culurgioni S, Alfieri A, Pendolino V, Laddomada F, Mapelli M. (2011) Inscuteable and NuMA proteins bind competitively to Leu-Gly-Asn repeat-enriched protein (LGN) during asymmetric cell divisions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:20998–21003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David NB, Martin CA, Segalen M, Rosenfeld F, Schweisguth F, Bellaïche Y. (2005) Drosophila Ric-8 regulates Galphai cortical localization to promote Galphai-dependent planar orientation of the mitotic spindle during asymmetric cell division. Nat Cell Biol 7:1083–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWire SM, Yamashita DS, Rominger DH, Liu G, Cowan CL, Graczyk TM, Chen XT, Pitis PM, Gotchev D, Yuan C, et al. (2013) A G protein-biased ligand at the μ-opioid receptor is potently analgesic with reduced gastrointestinal and respiratory dysfunction compared with morphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 344:708–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Horta O, Sirmaci A, Doherty D, Nance W, Arnos K, Pandya A, Tekin M. (2012) GPSM2 mutations in Chudley-McCullough syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 158A:2972–2973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty D, Chudley AE, Coghlan G, Ishak GE, Innes AM, Lemire EG, Rogers RC, Mhanni AA, Phelps IG, Jones SJ, et al. FORGE Canada Consortium (2012) GPSM2 mutations cause the brain malformations and hearing loss in Chudley-McCullough syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 90:1088–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q, Macara IG. (2004) Mammalian Pins is a conformational switch that links NuMA to heterotrimeric G proteins. Cell 119:503–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Q, Stukenberg PT, Macara IG. (2001) A mammalian Partner of inscuteable binds NuMA and regulates mitotic spindle organization. Nat Cell Biol 3:1069–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto A, Asai N, Namba T, Wang Y, Kato T, Tanaka M, Tatsumi H, Taya S, Tsuboi D, Kuroda K, et al. (2009) Roles of disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1-interacting protein girdin in postnatal development of the dentate gyrus. Neuron 63:774–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto A, Murakami H, Asai N, Morone N, Watanabe T, Kawai K, Murakumo Y, Usukura J, Kaibuchi K, Takahashi M. (2005) Akt/PKB regulates actin organization and cell motility via Girdin/APE. Dev Cell 9:389–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezan J, Lasvaux L, Gezer A, Novakovic A, May-Simera H, Belotti E, Lhoumeau AC, Birnbaumer L, Beer-Hammer S, Borg JP, et al. (2013) Primary cilium migration depends on G-protein signalling control of subapical cytoskeleton. Nat Cell Biol 15:1107–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk JD, Vargiu P, Foye PE, Usui H, Perez J, Danielson PE, Lerner DL, Bernal J, Sutcliffe JG. (1999) Rhes: A striatal-specific Ras homolog related to Dexras1. J Neurosci Res 57:782–788 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang M, Jaffrey SR, Sawa A, Ye K, Luo X, Snyder SH. (2000) Dexras1: a G protein specifically coupled to neuronal nitric oxide synthase via CAPON. Neuron 28:183–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukukawa C, Ueda K, Nishidate T, Katagiri T, Nakamura Y. (2010) Critical roles of LGN/GPSM2 phosphorylation by PBK/TOPK in cell division of breast cancer cells. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 49:861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay M, Pinter ME, Wright FA, Chan P, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, Yancopoulos GD, Tall GG. (2011) Ric-8 proteins are molecular chaperones that direct nascent G protein α subunit membrane association. Sci Signal 4:ra79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Marcos M, Ear J, Farquhar MG, Ghosh P. (2011a) A GDI (AGS3) and a GEF (GIV) regulate autophagy by balancing G protein activity and growth factor signals. Mol Biol Cell 22:673–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Marcos M, Ghosh P, Ear J, Farquhar MG. (2010) A structural determinant that renders G alpha(i) sensitive to activation by GIV/girdin is required to promote cell migration. J Biol Chem 285:12765–12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Marcos M, Ghosh P, Farquhar MG. (2009) GIV is a nonreceptor GEF for G alpha i with a unique motif that regulates Akt signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:3178–3183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Marcos M, Jung BH, Ear J, Cabrera B, Carethers JM, Ghosh P. (2011b) Expression of GIV/Girdin, a metastasis-related protein, predicts patient survival in colon cancer. FASEB J 25:590–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier-Fisher A, Lin DC, Greeve M, Kaplan DR, Rottapel R, Miller FD. (2009) Lfc and Tctex-1 regulate the genesis of neurons from cortical precursor cells. Nat Neurosci 12:735–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesty-Palmer D, Luttrell LM. (2011) ‘Biasing’ the parathyroid hormone receptor: a novel anabolic approach to increasing bone mass? Br J Pharmacol 164:59–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M, Peterson YK, Lanier SM, Smrcka AV. (2003) Receptor- and nucleotide exchange-independent mechanisms for promoting G protein subunit dissociation. J Biol Chem 278:34747–34750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Beas AO, Bornheimer SJ, Garcia-Marcos M, Forry EP, Johannson C, Ear J, Jung BH, Cabrera B, Carethers JM, et al. (2010) A Galphai-GIV molecular complex binds epidermal growth factor receptor and determines whether cells migrate or proliferate. Mol Biol Cell 21:2338–2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P, Garcia-Marcos M, Farquhar MG. (2011) GIV/Girdin is a rheostat that fine-tunes growth factor signals during tumor progression. Cell Adhes Migr 5:237–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giguère PM, Billard MJ, Laroche G, Buckley BK, Timoshchenko RG, McGinnis MW, Esserman D, Foreman O, Liu P, Siderovski DP, et al. (2013) G-protein signaling modulator-3, a gene linked to autoimmune diseases, regulates monocyte function and its deficiency protects from inflammatory arthritis. Mol Immunol 54:193–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giguère PM, Laroche G, Oestreich EA, Siderovski DP. (2012) G-protein signaling modulator-3 regulates heterotrimeric G-protein dynamics through dual association with Gβ and Gαi protein subunits. J Biol Chem 287:4863–4874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotta M, Dong Y, Peterson YK, Lanier SM, Ahringer J. (2003) Asymmetrically distributed C. elegans homologs of AGS3/PINS control spindle position in the early embryo. Curr Biol 13:1029–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TE, Key TA, Kilpatrick K, Dorin RI. (2001) Dexras1/AGS-1, a steroid hormone-induced guanosine triphosphate-binding protein, inhibits 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate-stimulated secretion in AtT-20 corticotroph cells. Endocrinology 142:2631–2640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TE, Prossnitz ER, Dorin RI. (2002) Dexras1/AGS-1 inhibits signal transduction from the Gi-coupled formyl peptide receptor to Erk-1/2 MAP kinases. J Biol Chem 277:10876–10882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham TE, Qiao Z, Dorin RI. (2004) Dexras1 inhibits adenylyl cyclase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 316:307–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves B, Abrahamsen H, Clingan H, Frantz M, Mavor L, Bailey J, Ma D. (2010) An inhibitory role of the G-protein regulator AGS3 in mTOR-dependent macroautophagy. PLoS ONE 5:e8877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves B, Gong Q, Xu Z, Huntsman C, Nguyen C, Li D, Ma D. (2007) A specific role of AGS3 in the surface expression of plasma membrane proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:18103–18108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampoelz B, Hoeller O, Bowman SK, Dunican D, Knoblich JA. (2005) Drosophila Ric-8 is essential for plasma-membrane localization of heterotrimeric G proteins. Nat Cell Biol 7:1099–1105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara K, Fujita H, Johnson TA, Yamauchi T, Yasuda K, Horikoshi M, Peng C, Hu C, Ma RC, Imamura M, et al. DIAGRAM Consortium (2014) Genome-wide association study identifies three novel loci for type 2 diabetes. Hum Mol Genet 23:239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LM, He Y. (2011) Rhes and AGS1/Dexras1 affect signaling by dopamine D1 receptors through adenylyl cyclase. J Neurosci Res 89:874–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LM, Muller SH, Spano D. (2013) Effects of the Ras homolog Rhes on Akt/protein kinase B and glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation in striatum. Neuroscience 236:21–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess HA, Röper JC, Grill SW, Koelle MR. (2004) RGS-7 completes a receptor-independent heterotrimeric G protein cycle to asymmetrically regulate mitotic spindle positioning in C. elegans. Cell 119:209–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C, Goddard A, Ladds G, Davey J. (2009) The cationic region of Rhes mediates its interactions with specific Gbeta subunits. Cell Physiol Biochem 23:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiskens R, Vatish M, Hill C, Davey J, Ladds G. (2005) Specific in vivo binding of activator of G protein signalling 1 to the Gbeta1 subunit. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 337:1038–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofler C, Koelle MR. (2011) AGS-3 alters Caenorhabditis elegans behavior after food deprivation via RIC-8 activation of the neural G protein G αo. J Neurosci 31:11553–11562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyghe JR, Jackson AU, Fogarty MP, Buchkovich ML, Stančáková A, Stringham HM, Sim X, Yang L, Fuchsberger C, Cederberg H, et al. (2013) Exome array analysis identifies new loci and low-frequency variants influencing insulin processing and secretion. Nat Genet 45:197–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaki T, Kamakura S, Kohjima M, Sumimoto H. (2006) Two forms of human Inscuteable-related protein that links Par3 to the Pins homologues LGN and AGS3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 341:1001–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffrey SR, Fang M, Snyder SH. (2002) Nitrosopeptide mapping: a novel methodology reveals s-nitrosylation of dexras1 on a single cysteine residue. Chem Biol 9:1329–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia M, Li J, Zhu J, Wen W, Zhang M, Wang W. (2012) Crystal structures of the scaffolding protein LGN reveal the general mechanism by which GoLoco binding motifs inhibit the release of GDP from Gαi. J Biol Chem 287:36766–36776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamakura S, Nomura M, Hayase J, Iwakiri Y, Nishikimi A, Takayanagi R, Fukui Y, Sumimoto H. (2013) The cell polarity protein mInsc regulates neutrophil chemotaxis via a noncanonical G protein signaling pathway. Dev Cell 26:292–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katritch V, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. (2013) Structure-function of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 53:531–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly E. (2013) Efficacy and ligand bias at the μ-opioid receptor. Br J Pharmacol 169:1430–1446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemppainen RJ, Behrend EN. (1998) Dexamethasone rapidly induces a novel ras superfamily member-related gene in AtT-20 cells. J Biol Chem 273:3129–3131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. (2012) Casting a wider net: whole-cell assays to capture varied and biased signaling. Mol Pharmacol 82:571–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T, Christopoulos A. (2013) Signalling bias in new drug discovery: detection, quantification and therapeutic impact. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12:205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimple RJ, Kimple ME, Betts L, Sondek J, Siderovski DP. (2002) Structural determinants for GoLoco-induced inhibition of nucleotide release by Galpha subunits. Nature 416:878–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, Asai N, Enomoto A, Maeda K, Kato T, Ishida M, Jiang P, Watanabe T, Usukura J, Kondo T, et al. (2008) Regulation of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis by the Akt/PKB substrate Girdin. Nat Cell Biol 10:329–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopein D, Katanaev VL. (2009) Drosophila GoLoco-protein Pins is a target of Galpha(o)-mediated G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Mol Biol Cell 20:3865–3877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon M, Pavlov TS, Nozu K, Rasmussen SA, Ilatovskaya DV, Lerch-Gaggl A, North LM, Kim H, Qian F, Sweeney WE, Jr, et al. (2012) G-protein signaling modulator 1 deficiency accelerates cystic disease in an orthologous mouse model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:21462–21467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le-Niculescu H, Niesman I, Fischer T, Devries L, Farquhar MG. (2005) Identification and characterization of GIV, a novel Galpha i/s interacting protein found on COPI, endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi transport vesicles. J Biol Chem 280:22012–22020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechler T, Fuchs E. (2005) Asymmetric cell divisions promote stratification and differentiation of mammalian skin. Nature 437:275–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MJ, Dohlman HG. (2008) Coactivation of G protein signaling by cell-surface receptors and an intracellular exchange factor. Curr Biol 18:211–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lellis-Santos C, Sakamoto LH, Bromati CR, Nogueira TC, Leite AR, Yamanaka TS, Kinote A, Anhê GF, Bordin S. (2012) The regulation of Rasd1 expression by glucocorticoids and prolactin controls peripartum maternal insulin secretion. Endocrinology 153:3668–3678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Zhang Y, Xu H, Zhang R, Li H, Lu P, Jin F. (2012) Girdin protein: a new potential distant metastasis predictor of breast cancer. Med Oncol 29:1554–1560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Palacino J. (2013) A novel human embryonic stem cell-derived Huntington’s disease neuronal model exhibits mutant huntingtin (mHTT) aggregates and soluble mHTT-dependent neurodegeneration. FASEB J 27:1820–1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao JZ, Jiang P, Cui SP, Ren YL, Zhao J, Yin XH, Enomoto A, Liu HJ, Hou L, Takahashi M, et al. (2012) Girdin locates in centrosome and midbody and plays an important role in cell division. Cancer Sci 103:1780–1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath MF, Ogawa T, de Bold AJ. (2012) Ras dexamethasone-induced protein 1 is a modulator of hormone secretion in the volume overloaded heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302:H1826–H1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mealer RG, Subramaniam S, Snyder SH. (2013) Rhes deletion is neuroprotective in the 3-nitropropionic acid model of Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci 33:4206–4210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal V, Linder ME. (2004) The RGS14 GoLoco domain discriminates among Galphai isoforms. J Biol Chem 279:46772–46778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadella R, Blumer JB, Jia G, Kwon M, Akbulut T, Qian F, Sedlic F, Wakatsuki T, Sweeney WE, Jr, Wilson PD, et al. (2010) Activator of G protein signaling 3 promotes epithelial cell proliferation in PKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 21:1275–1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair KS, Mendez A, Blumer JB, Rosenzweig DH, Slepak VZ. (2005) The presence of a Leu-Gly-Asn repeat-enriched protein (LGN), a putative binding partner of transducin, in ROD photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 46:383–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen CH, Watts VJ. (2005) Dexras1 blocks receptor-mediated heterologous sensitization of adenylyl cyclase 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 332:913–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nipper RW, Siller KH, Smith NR, Doe CQ, Prehoda KE. (2007) Galphai generates multiple Pins activation states to link cortical polarity and spindle orientation in Drosophila neuroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:14306–14311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara K, Enomoto A, Kato T, Hashimoto T, Isotani-Sakakibara M, Asai N, Ishida-Takagishi M, Weng L, Nakayama M, Watanabe T, et al. (2012) Involvement of Girdin in the determination of cell polarity during cell migration. PLoS ONE 7:e36681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto S, Pouladi MA, Talantova M, Yao D, Xia P, Ehrnhoefer DE, Zaidi R, Clemente A, Kaul M, Graham RK, et al. (2009) Balance between synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activity influences inclusions and neurotoxicity of mutant huntingtin. Nat Med 15:1407–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oner SS, An N, Vural A, Breton B, Bouvier M, Blumer JB, Lanier SM. (2010a) Regulation of the AGS3·Galphai signaling complex by a seven-transmembrane span receptor. J Biol Chem 285:33949–33958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oner SS, Maher EM, Breton B, Bouvier M, Blumer JB. (2010b) Receptor-regulated interaction of activator of G-protein signaling-4 and Galphai. J Biol Chem 285:20588–20594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oner SS, Maher EM, Gabay M, Tall GG, Blumer JB, Lanier SM. (2013a) Regulation of the G-protein regulatory-Gαi signaling complex by nonreceptor guanine nucleotide exchange factors. J Biol Chem 288:3003–3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oner SS, Vural A, Lanier SM. (2013b) Translocation of activator of G-protein signaling 3 to the Golgi apparatus in response to receptor activation and its effect on the trans-Golgi network. J Biol Chem 288:24091–24103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z, Zhu J, Shang Y, Wei Z, Jia M, Xia C, Wen W, Wang W, Zhang M. (2013) An autoinhibited conformation of LGN reveals a distinct interaction mode between GoLoco motifs and TPR motifs. Structure 21:1007–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier ML, Woods D, Greig S, Phan PG, Radovic A, Bryant P, O’Kane CJ. (2000) Rapsynoid/partner of inscuteable controls asymmetric division of larval neuroblasts in Drosophila. J Neurosci 20:RC84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattingre S, De Vries L, Bauvy C, Chantret I, Cluzeaud F, Ogier-Denis E, Vandewalle A, Codogno P. (2003) The G-protein regulator AGS3 controls an early event during macroautophagy in human intestinal HT-29 cells. J Biol Chem 278:20995–21002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan AA, Smith ML, Kieffer BL, Evans CJ. (2012) Ligand-directed signalling within the opioid receptor family. Br J Pharmacol 167:960–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SG, DeVree BT, Zou Y, Kruse AC, Chung KY, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Chae PS, Pardon E, Calinski D, et al. (2011) Crystal structure of the β2 adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature 477:549–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regner KR, Nozu K, Lanier SM, Blumer JB, Avner ED, Sweeney WE, Jr, Park F. (2011) Loss of activator of G-protein signaling 3 impairs renal tubular regeneration following acute kidney injury in rodents. FASEB J 25:1844–1855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter E, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Lefkowitz RJ. (2012) Molecular mechanism of β-arrestin-biased agonism at seven-transmembrane receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 52:179–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivero G, Llorente J, McPherson J, Cooke A, Mundell SJ, McArdle CA, Rosethorne EM, Charlton SJ, Krasel C, Bailey CP, et al. (2012) Endomorphin-2: a biased agonist at the μ-opioid receptor. Mol Pharmacol 82:178–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev P, Menon S, Kastner DB, Chuang JZ, Yeh TY, Conde C, Caceres A, Sung CH, Sakmar TP. (2007) G protein beta gamma subunit interaction with the dynein light-chain component Tctex-1 regulates neurite outgrowth. EMBO J 26:2621–2632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanada K, Tsai LH. (2005) G protein betagamma subunits and AGS3 control spindle orientation and asymmetric cell fate of cerebral cortical progenitors. Cell 122:119–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Blumer JB, Simon V, Lanier SM. (2006a) Accessory proteins for G proteins: partners in signaling. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 46:151–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Cismowski MJ, Toyota E, Smrcka AV, Lucchesi PA, Chilian WM, Lanier SM. (2006b) Identification of a receptor-independent activator of G protein signaling (AGS8) in ischemic heart and its interaction with Gbetagamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:797–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Gettys TW, Lanier SM. (2004) AGS3 and signal integration by Galpha(s)- and Galpha(i)-coupled receptors: AGS3 blocks the sensitization of adenylyl cyclase following prolonged stimulation of a Galpha(i)-coupled receptor by influencing processing of Galpha(i). J Biol Chem 279:13375–13382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Hiraoka M, Suzuki H, Bai Y, Kurotani R, Yokoyama U, Okumura S, Cismowski MJ, Lanier SM, Ishikawa Y. (2011) Identification of transcription factor E3 (TFE3) as a receptor-independent activator of Galpha16: Gene regulation by nuclear Galpha subunit and its activator. J Biol Chem 286:17766–17776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Jiao Q, Honda T, Kurotani R, Toyota E, Okumura S, Takeya T, Minamisawa S, Lanier SM, Ishikawa Y. (2009) Activator of G protein signaling 8 (AGS8) is required for hypoxia-induced apoptosis of cardiomyocytes: Role of G betagamma and connexin43 (CX43). J Biol Chem 284:31431–31440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M, Petronczki M, Dorner D, Forte M, Knoblich JA. (2001) Heterotrimeric G proteins direct two modes of asymmetric cell division in the Drosophila nervous system. Cell 107:183–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M, Shevchenko A, Shevchenko A, Knoblich JA. (2000) A protein complex containing Inscuteable and the Galpha-binding protein Pins orients asymmetric cell divisions in Drosophila. Curr Biol 10:353–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RA, Lagou V, Welch RP, Wheeler E, Montasser ME, Luan J, Mägi R, Strawbridge RJ, Rehnberg E, Gustafsson S, et al. DIAbetes Genetics Replication and Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium (2012) Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nat Genet 44:991–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spano D, Branchi I, Rosica A, Pirro MT, Riccio A, Mithbaokar P, Affuso A, Arra C, Campolongo P, Terracciano D, et al. (2004) Rhes is involved in striatal function. Mol Cell Biol 24:5788–5796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan DG, Fisk RM, Xu H, van den Heuvel S. (2003) A complex of LIN-5 and GPR proteins regulates G protein signaling and spindle function in C elegans. Genes Dev 17:1225–1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam S, Sixt KM, Barrow R, Snyder SH. (2009) Rhes, a striatal specific protein, mediates mutant-huntingtin cytotoxicity. Science 324:1327–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Umeda N, Tsutsumi Y, Fukumura R, Ohkaze H, Sujino M, van der Horst G, Yasui A, Inouye ST, Fujimori A, et al. (2003) Mouse dexamethasone-induced RAS protein 1 gene is expressed in a circadian rhythmic manner in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 110:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takesono A, Cismowski MJ, Ribas C, Bernard M, Chung P, Hazard S, 3rd, Duzic E, Lanier SM. (1999) Receptor-independent activators of heterotrimeric G-protein signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 274:33202–33205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takesono A, Nowak MW, Cismowski M, Duzic E, Lanier SM. (2002) Activator of G-protein signaling 1 blocks GIRK channel activation by a G-protein-coupled receptor: apparent disruption of receptor signaling complexes. J Biol Chem 277:13827–13830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tall GG. (2013) Ric-8 regulation of heterotrimeric G proteins. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 33:139–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tall GG, Gilman AG. (2005) Resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase 8A catalyzes release of Galphai-GTP and nuclear mitotic apparatus protein (NuMA) from NuMA/LGN/Galphai-GDP complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:16584–16589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tall GG, Krumins AM, Gilman AG. (2003) Mammalian Ric-8A (synembryn) is a heterotrimeric Galpha protein guanine nucleotide exchange factor. J Biol Chem 278:8356–8362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapliyal A, Bannister RA, Hanks C, Adams BA. (2008) The monomeric G proteins AGS1 and Rhes selectively influence Galphai-dependent signaling to modulate N-type (CaV2.2) calcium channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295:C1417–C1426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CJ, Tall GG, Adhikari A, Sprang SR. (2008) Ric-8A catalyzes guanine nucleotide exchange on G alphai1 bound to the GPR/GoLoco exchange inhibitor AGS3. J Biol Chem 283:23150–23160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tõnissoo T, Kõks S, Meier R, Raud S, Plaas M, Vasar E, Karis A. (2006) Heterozygous mice with Ric-8 mutation exhibit impaired spatial memory and decreased anxiety. Behav Brain Res 167:42–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tõnissoo T, Lulla S, Meier R, Saare M, Ruisu K, Pooga M, Karis A. (2010) Nucleotide exchange factor RIC-8 is indispensable in mammalian early development. Dev Dyn 239:3404–3415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidyanathan G, Cismowski MJ, Wang G, Vincent TS, Brown KD, Lanier SM. (2004) The Ras-related protein AGS1/RASD1 suppresses cell growth. Oncogene 23:5858–5863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargiu P, De Abajo R, Garcia-Ranea JA, Valencia A, Santisteban P, Crespo P, Bernal J. (2004) The small GTP-binding protein, Rhes, regulates signal transduction from G protein-coupled receptors. Oncogene 23:559–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellano CP, Brown NE, Blumer JB, Hepler JR. (2013) Assembly and function of the regulator of G protein signaling 14 (RGS14)·H-Ras signaling complex in live cells are regulated by Gαi1 and Gαi-linked G protein-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem 288:3620–3631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellano CP, Maher EM, Hepler JR, Blumer JB. (2011) G protein-coupled receptors and resistance to inhibitors of cholinesterase-8A (Ric-8A) both regulate the regulator of g protein signaling 14 RGS14·Gαi1 complex in live cells. J Biol Chem 286:38659–38669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vural A, Oner S, An N, Simon V, Ma D, Blumer JB, Lanier SM. (2010) Distribution of activator of G-protein signaling 3 within the aggresomal pathway: role of specific residues in the tetratricopeptide repeat domain and differential regulation by the AGS3 binding partners Gi(alpha) and mammalian inscuteable. Mol Cell Biol 30:1528–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T, Shahin H, Elkan-Miller T, Lee MK, Thornton AM, Roeb W, Abu Rayyan A, Loulus S, Avraham KB, King MC, et al. (2010) Whole exome sequencing and homozygosity mapping identify mutation in the cell polarity protein GPSM2 as the cause of nonsyndromic hearing loss DFNB82. Am J Hum Genet 87:90–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Ng KH, Qian H, Siderovski DP, Chia W, Yu F. (2005) Ric-8 controls Drosophila neural progenitor asymmetric division by regulating heterotrimeric G proteins. Nat Cell Biol 7:1091–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kaneko N, Asai N, Enomoto A, Isotani-Sakakibara M, Kato T, Asai M, Murakumo Y, Ota H, Hikita T, et al. (2011) Girdin is an intrinsic regulator of neuroblast chain migration in the rostral migratory stream of the postnatal brain. J Neurosci 31:8109–8122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehbi VL, Stevenson HP, Feinstein TN, Calero G, Romero G, Vilardaga JP. (2013) Noncanonical GPCR signaling arising from a PTH receptor-arrestin-Gβγ complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:1530–1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard FS, Kimple RJ, Siderovski DP. (2004) Return of the GDI: the GoLoco motif in cell division. Annu Rev Biochem 73:925–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard FS, Zheng Z, Guo J, Digby GJ, Kimple AJ, Conley JM, Johnston CA, Bosch D, Willard MD, Watts VJ, et al. (2008) A point mutation to Galphai selectively blocks GoLoco motif binding: direct evidence for Galpha.GoLoco complexes in mitotic spindle dynamics. J Biol Chem 283:36698–36710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SE, Beronja S, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. (2011) Asymmetric cell divisions promote Notch-dependent epidermal differentiation. Nature 470:353–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiser O, Qian X, Ehlers M, Ja WW, Roberts RW, Reuveny E, Jan YN, Jan LY. (2006) Modulation of basal and receptor-induced GIRK potassium channel activity and neuronal excitability by the mammalian PINS homolog LGN. Neuron 50:561–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodard GE, Huang NN, Cho H, Miki T, Tall GG, Kehrl JH. (2010) Ric-8A and Gi alpha recruit LGN, NuMA, and dynein to the cell cortex to help orient the mitotic spindle. Mol Cell Biol 30:3519–3530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootten D, Simms J, Miller LJ, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM. (2013) Polar transmembrane interactions drive formation of ligand-specific and signal pathway-biased family B G protein-coupled receptor conformations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:5211–5216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L, McFarland K, Fan P, Jiang Z, Inoue Y, Diamond I. (2005) Activator of G protein signaling 3 regulates opiate activation of protein kinase A signaling and relapse of heroin-seeking behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:8746–8751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao L, McFarland K, Fan P, Jiang Z, Ueda T, Diamond I. (2006) Adenosine A2a blockade prevents synergy between mu-opiate and cannabinoid CB1 receptors and eliminates heroin-seeking behavior in addicted rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:7877–7882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yariz KO, Walsh T, Akay H, Duman D, Akkaynak AC, King MC, Tekin M. (2012) A truncating mutation in GPSM2 is associated with recessive nonsyndromic hearing loss. Clin Genet 81:289–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh C, Li A, Chuang JZ, Saito M, Cáceres A, Sung CH. (2013) IGF-1 activates a cilium-localized noncanonical Gβγ signaling pathway that regulates cell-cycle progression. Dev Cell 26:358–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiura S, Ohta N, Matsuzaki F. (2012) Tre1 GPCR signaling orients stem cell divisions in the Drosophila central nervous system. Dev Cell 22:79–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Morin X, Cai Y, Yang X, Chia W. (2000) Analysis of partner of inscuteable, a novel player of Drosophila asymmetric divisions, reveals two distinct steps in inscuteable apical localization. Cell 100:399–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan C, Sato M, Lanier SM, Smrcka AV. (2007) Signaling by a non-dissociated complex of G protein βγ and α subunits stimulated by a receptor-independent activator of G protein signaling, AGS8. J Biol Chem 282:19938–19947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuzawa S, Kamakura S, Iwakiri Y, Hayase J, Sumimoto H. (2011) Structural basis for interaction between the conserved cell polarity proteins Inscuteable and Leu-Gly-Asn repeat-enriched protein (LGN). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:19210–19215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Nguyen CH, Chidiac P. (2010) The proline-rich N-terminal domain of G18 exhibits a novel G protein regulatory function. J Biol Chem 285:9008–9017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Wan Q, Liu J, Zhu H, Chu X, Du Q. (2013) Evidence for dynein and astral microtubule-mediated cortical release and transport of Gαi/LGN/NuMA complex in mitotic cells. Mol Biol Cell 24:901–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Zhu H, Wan Q, Liu J, Xiao Z, Siderovski DP, Du Q. (2010) LGN regulates mitotic spindle orientation during epithelial morphogenesis. J Cell Biol 189:275–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Wen W, Zheng Z, Shang Y, Wei Z, Xiao Z, Pan Z, Du Q, Wang W, Zhang M. (2011) LGN/mInsc and LGN/NuMA complex structures suggest distinct functions in asymmetric cell division for the Par3/mInsc/LGN and Gαi/LGN/NuMA pathways. Mol Cell 43:418–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigman M, Cayouette M, Charalambous C, Schleiffer A, Hoeller O, Dunican D, McCudden CR, Firnberg N, Barres BA, Siderovski DP, et al. (2005) Mammalian inscuteable regulates spindle orientation and cell fate in the developing retina. Neuron 48:539–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]