Abstract

Introduction: Clerkships are still the main source for undergraduate medical students to acquire necessary skills. However, these educational experiences may not be sufficient, as there are significant deficiencies in the clinical experience and practical expertise of medical students.

Project description: An innovative course teaching basic clinical and procedural skills to first-year medical students has been implemented at the Medical University of Graz, aiming at preparing students for clerkships and clinical electives. The course is based on several didactic elements: standardized and clinically relevant contents, dual (theoretical and virtual) pre-course preparation, student peer-teaching, small teaching groups, hands-on training, and the use of medical simulation. This is the first course of its kind at a medical school in Austria, and its conceptual design as well as the implementation process into the curriculum shall be described.

Evaluation: Between November 2011 and January 2013, 418 students have successfully completed the course. Four online surveys among participating students have been performed, with 132 returned questionnaires. Students’ satisfaction with all four practical course parts was high, as well as the assessment of clinical relevance of contents. Most students (88.6%) strongly agreed/agreed that they had learned a lot throughout the course. Two thirds of the students were motivated by the course to train the acquired skills regularly at our skills laboratory. Narrative feedbacks revealed elements contributing most to course success.

Conclusions: First-year medical students highly appreciate practical skills training. Hands-on practice, peer-teaching, clinically relevant contents, and the use of medical simulation are valued most.

Keywords: Clinical skills, skills laboratory, practical training, undergraduate education, medical simulation

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung: Medizinstudierende erlernen erforderliche Fertigkeiten nach wie vor primär im Rahmen von Praktika und Famulaturen. Diese Form der praktischen Ausbildung erscheint jedoch als nicht ausreichend, da signifikante Defizite in der klinischen Erfahrung und praktischen Kompetenz von Medizinstudierenden bestehen.

Projektbeschreibung: An der Medizinischen Universität Graz wurde eine innovative Lehrveranstaltung eingeführt, um erstjährigen Medizinstudierenden die Durchführung grundlegender klinischer Fertigkeiten und praktischer Maßnahmen als Vorbereitung auf Famulaturen und Praktika zu vermitteln. Die Lehrveranstaltung basiert auf mehreren didaktischen Elementen: Standardisierte, klinisch relevante Lehrinhalte, duale (theoretische und virtuelle) Vorbereitung, studentisches Peer-Teaching, Kleingruppenunterricht, praktisches Training und die Verwendung medizinischer Simulation. Dies ist die erste Lehrveranstaltung dieser Art an einer österreichischen Medizinuniversität, und das Konzept sowie die Implementierung in das Curriculum sollen zur Beschreibung gelangen.

Evaluierung: Zwischen November 2011 und Januar 2013 haben 418 Studierende erfolgreich an der Lehrveranstaltung teilgenommen. Es wurden vier Online-Evaluierungen unter den teilnehmenden Studierenden durchgeführt und 132 Fragebögen beantwortet. Die studentische Zufriedenheit mit allen vier praktischen Lehrveranstaltungsteilen war ebenso wie die Beurteilung der klinischen Relevanz der Lehrinhalte hoch. Die meisten Studierenden (88,6%) stimmten zu, im Rahmen der Lehrveranstaltung viel gelernt zu haben. Zwei Drittel der Studierenden wurden motiviert, die erworbenen Fähigkeiten regelmäßig in unserem klinischen Trainingszentrum zu trainieren. Die am meisten geschätzten Lehrveranstaltungsaspekte wurden durch Auswertung der Freitextevaluierungen identifiziert.

Schlussfolgerung: Praktisches Fertigkeitentraining wird von erstjährigen Medizinstudierenden mit großem Enthusiasmus angenommen. Am meisten geschätzt werden die Möglichkeit aktiven Trainings, Peer-Teaching, klinisch relevante Lehrinhalte und die Nutzung medizinischer Simulation.

Introduction

The achievement of clinical competence is a gradual process, and repetitive training is a central element of this educational continuum [1], [2], [3]. Traditional medical curricula rely primarily on clerkships during the clinical period of study to acquire and train clinical skills, while the preclinical period is mainly used to teach basic sciences [4]. However, an investigation using student focus groups showed that junior clerkships were predominantly passive experiences with hardly any opportunity to train clinical skills [5]. Accordingly, Nielsen et al. [6] reported that the chances of training practical procedures during clerkships are scarce and that medical students have to work hard in order to be able to perform relevant skills.

Several studies have identified a lack of clinical experience and practical competence by medical students [4], [7], [8], [9]. Limited practical experience, however, leads to reduced self-confidence, hesitancy, and anxiety in students due to fear of causing harm to patients [10], [11]. In addition, there are currently no standardized tools to assess procedural skills competence of medical students prior to certification, leading to inequity of assessment and competence before qualification [12].

Two concepts aiming at preparing medical students better for the demands of their future profession are problem-based learning and the introduction of basic clinical skills courses [13].

Medical University of Graz

At the Medical University of Graz, the human medicine curriculum covers six years and is divided into three stages [http://www.medunigraz.at/images/content/file/studium/humanmedizin/pdf/studienplan_v11_01102013.pdf, last viewed on 17.09.2013]. During the first phase of study – lasting for one year – mainly natural sciences are taught, supplemented with an internship at a hospital ward. During the subsequent four years a modular system provides students with the required medical knowledge using clerkships to teach and train clinical skills. Within these four years students have to go through 16 weeks (560 hours) of mandatory electives. Clerkships are predetermined clinical placements as part of the main curriculum, whereas electives are mandatory clinical activities of students in medical specialties of their own choice (see Attachment 1). In order to complete the second stage of study students have to pass an OSCE, testing the performance of clinical skills and practical procedures. The course of study is finalized by another two semesters spent working at three hospital wards of different specialization and at a family physician.

In this article we want to report on the conceptual design and implementation of a novel course teaching basic clinical and procedural skills to first-year students. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first course of its kind at a medical school in Austria. Furthermore, we are going to present the results of initial course evaluations.

Project description

In spring 2011, the Curriculum Commission decided to introduce a practical course aiming at preparing preclinical students better for compulsory clerkships and electives. A work group was established, consisting of teachers of different medical specialties and of two experienced medical students working as student instructors at our Clinical Skills Center (CSC). Skills deemed as essential were identified on the basis of the recently introduced Austrian Catalogue of Competence for Medical Skills [14], which is comparable to the Swiss Catalogue of Learning Objectives for Undergraduate Medical Training and the German Consensus Statement on Practical Skills in Medical School [15], [16].

In June 2011, a new practical course called “Clinical Elective License” (CEL) was implemented into the human medicine curriculum of the Medical University of Graz. It was designated as a compulsory course for first-year students. The CEL encompasses one European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) point corresponding to 25 hours of actual work. For successful completion, students have to attend at least 85 per cent of the lessons and demonstrate sufficient theoretical preparation as well as active cooperation. In November 2011, first CEL courses were held.

In order to guarantee appropriate pre-course preparation, CSC peer-teachers have compiled the “Graz’ Skills Guide” under guidance and supervision of clinical teachers. Beginning with necessary anatomical and physiological knowledge, this handbook describes the performance of clinical skills and procedures by using written text, procedural algorithms, and high-quality image series specifically developed for the course. The “Graz’ Skills Guide” is available online and free of charge for every student at the Medical University of Graz.

Course contents

The CEL is a six-part course with two virtual and four practical phases. After having worked through the “Graz’ Skills Guide”, students have to pass a Web-Based-Training (WBT) featuring multiple-choice questions summarizing the subjects taught. Ten hours have been designated as practical training time, four hours for the first and two hours for each of the following course parts. Teaching groups consist of three to six students at most, with every group being tutored by one of our CSC peer-teachers.

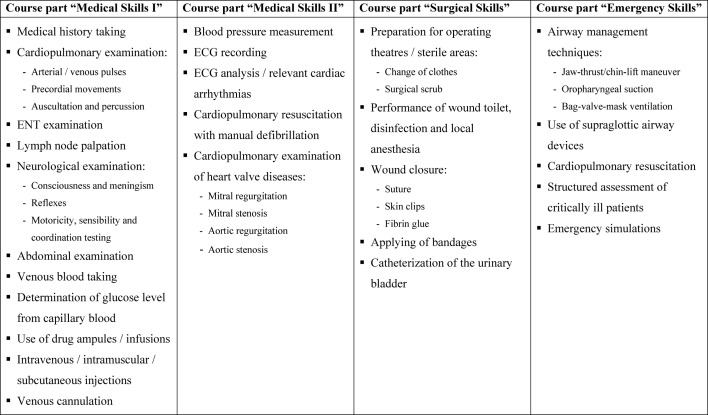

The first practical part of the CEL (“Medical Skills I”) provides students with skills regarding medical history taking, physical examination, and common (non-)invasive procedures (see Table 1 (Tab. 1)). Course participants learn how to take medical histories in a structured manner through patient-doctor role plays. Physical examination techniques are trained on a cardiopulmonary patient simulator and on fellow course participants. Practice of relevant procedures, such as blood taking and injections, concludes the course.

Table 1. Contents of the practical course parts of the “Clinical Elective License”.

The second practical course part “Medical Skills II” focuses on the cardiovascular system (see Table 1 (Tab. 1)). Students learn diagnostic modalities (blood pressure measurement, electrocardiography recording), get to know important cardiac arrhythmias, train cardiopulmonary resuscitation and manual defibrillation, and recapitulate the main points of cardiovascular examination by working through four common heart valve diseases on our cardiopulmonary patient simulator.

The third practical CEL part (“Surgical Skills”) deals with principles of working in sterile areas, desmurgia, and wound care (see Table 1 (Tab. 1)). In our simulation operating theatre, students learn how to prepare for aseptic interventions, are shown the performance of wound toilet, disinfection, and local anesthesia, and train different forms of wound closure. Rounding out the course, catheterization of the urinary bladder is practiced on urologic manikins.

The course “Emergency Skills” concludes the practical CEL parts (see Table 1 (Tab. 1)). First, airway management techniques are trained. With the aid of a simulation software, students learn how to apply the ABCDE approach (Airway/Breathing/Circulation/Disability/Exposure) and get to know clinical characteristics of different medical emergencies. Short emergency simulations using high-fidelity patient simulators finalize the course. The medical emergencies trained are the ones previously used in the virtual course part. The goal of the simulation sequences is the integrated practice of skills acquired throughout the CEL in a realistic setting.

In order to pass the CEL, students have to complete a second WBT. Its multiple-choice questions focus on the contents of the practical courses.

Course principles

The CEL is based on several didactic elements: standardized and clinically relevant contents, dual (theoretical and virtual) pre-course preparation, student peer-teaching, small teaching groups, hands-on training, and the use of medical simulation. The course parts build on each other and contain repetitive sequences for maximization of learning outcomes. In addition to the compulsory courses, students are invited to train at our CSC in their course-free time.

Course evaluation

Four course evaluations have been carried out so far (February, May, and July 2012; February 2013). Between November 2011 and February 2013, 418 students have successfully participated in the CEL. Every student who had passed at least one practical course part at the time of the respective evaluation was defined eligible for our study and asked to complete an online questionnaire on a voluntary basis. The standard course questionnaires of the Medical University of Graz were used. Answers could be given on a six-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (“I totally agree”) to 6 (“I totally disagree”). We combined the results of these evaluations. Ratings are displayed as mean value ± one standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS Statistics, Version 20.

For a more detailed feedback, we included open questions. These asked students

what they liked most about the CEL, and

about suggestions for improvement.

The narrative statements were categorized; ‘n’ refers to the number of references to respective topics.

Evaluation

A total number of 132 students voluntarily participated in the course evaluation and, therefore, 132 completed questionnaires were included in our analysis. Seventy-six (57.6%) of the 132 students were male, 98 (74.2%) were between twenty and twenty-five years of age, and 30 (22.7%) were below the age of twenty. Every student had completed “Medical Skills I”, 110 students (83.3%) had passed “Medical Skills II”, 96 students (72.7%) had finished “Surgical Skills”, and 72 students (54.5%) “Emergency Skills”.

Item analysis

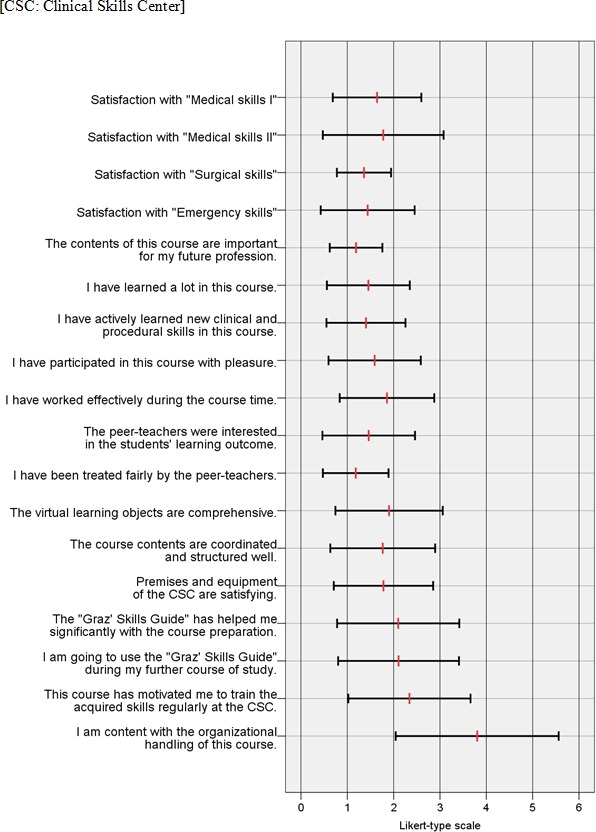

Students’ satisfaction with all four practical course parts was high, with ratings ranging from 1.4±0.6 to 1.8±1.3 (mean value ± one standard deviation). Students strongly agreed that the contents of the CEL were important for their future profession (1.2±0.6). Statements referring to perceived theoretical and practical learning outcomes both received high approval (1.5±0.9 and 1.4±0.9, respectively).

Most students participated with pleasure (1.6±1.0) and reported to have worked effectively during the course (1.9±1.0). The peer-teachers were perceived as being very interested in students’ learning outcome (1.5±1.0). Two thirds of the students (65.2%) strongly agreed/agreed that the CEL had motivated them to train the acquired clinical skills regularly at the CSC. Further details of course evaluations are summarized in Figure 1 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Questionnaire items and students’ evaluation ratings: mean value (red line) ± standard deviation (black bar).

Free-text analysis

Almost all comments about positive aspects of the CEL could be attributed to one of four categories. These were the active training of various skills (n=38), the peer-teachers’ motivation and expertise (n=27), clinically relevant course contents (n=26), and the use of simulation-based education (n=11).

Analysis of free-text comments revealed four major topics for course improvement. Most suggestions referred to longer course duration and more time for practical training (n=44). Twenty-seven comments asked for organizational adaptions, especially regarding the enrolment process. Splitting of “Medical Skills I” into two courses due to its considerable volume and reduction of theoretical course contents were mentioned 14 times each.

Discussion

First evaluations have displayed high student satisfaction with the CEL concept. Students especially valued the opportunity to actively practice various clinical skills, the quality of our peer-teachers, clinical relevance of course contents, and the use of simulation-based education.

The course evaluations revealed possibilities for improvement as well. The most frequent suggestion was the extension of course duration. Although difficult to implement given the tight timetable of first-year students, this idea will receive ample consideration. Improving the organizational handling of the CEL was another focal point. Initially, students chose course dates individually via our online course system. However, during the first months a handful of CEL courses was cancelled due to low numbers of enrolled students (<3). Reacting to numerous suggestions, course dates have been set for each student starting with the study year 2012/13. This predetermined CEL schedule now allows for numerically equal course groups, guarantees courses and reduces students’ organizational burden, leading to improved student satisfaction.

It has to be evaluated how well the skills acquired at our CSC will translate into the clinical stage of study. It must not be forgotten that training in the skills laboratory does not replace, but supplement clinical experience [10]. However, in the study by Nielsen et al. [6] 70 per cent of students were convinced to be able to transfer skills from the educational laboratory into patient treatment. Students within an innovative curriculum with skills laboratory training from the first year of study are better trained in basic clinical skills and, therefore, better prepared for clerkships, compared to students in traditional curricula [17]. In addition, Liddell and colleagues [18] proved that a single basic skills tutorial during the early part of medical study has a long-lasting positive effect on students’ clinical performance and reduces hesitancy to practice procedures during clerkships. Thus, we are optimistic that the CEL provides students with the necessary competence and confidence to successfully perform medical skills and practical procedures in the clinical setting.

Limitations

As our primary objective was to assess students’ perception of the course concept, we did not investigate their performance after completion of the CEL. However, further investigations addressing students’ short- and long-term competence and the transferability of skills into patient care are already being carried out.

Conclusions

The CEL concept has proven its value for students at the Medical University of Graz. Based on first course evaluations, factors contributing most to this success are hands-on training, motivated and experienced student instructors, clinically relevant contents, and the utilization of medical simulation. The most common suggestion for improvement was an extension of course duration. Additional research on students’ competence in the short- and long-term and on possible improvements in patient care will ultimately decide the CEL’s educational value.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Elisabeth Koch for performing course evaluations and data acquisition, Dominik Födinger and all other current and former CSC peer-teachers for their commitment, and each and every student who has evaluated the course and offered suggestions for improvement.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Carraccio CL, Benson BJ, Nixon LJ, Derstine PL. From the educational bench to the clinical bedside: translating the Dreyfus developmental model to the learning of clinical skills. Acad Med. 2008;83(8):761–777. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31817eb632. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31817eb632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ericsson KA, Krampe RT, Tesch-Römer C. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychol Rev. 1993;100(3):363–406. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.3.363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ten Cate O, Snell L, Carraccio C. Medical competence: the interplay between individual ability and the health care environment. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):669–675. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2010.500897. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.500897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Remmen R, Scherpbier A, Derese A, Denekens J, Hermann I, Van der Vleuten C, Van Royen P, Bossaert L. Unsatisfactory basic skills performance by students in traditional medical curricula. Med Teach. 1998;20(6):579–582. doi: 10.1080/01421599880328. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01421599880328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remmen R, Denekens J, Scherpbier AJ, Van der Vleuten CP, Hermann I, Van Puymbroeck H, Bossaert L. Evaluation of skills training during clerkships using student focus groups. Med Teach. 1998;20(5):428–432. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nielsen DG, Moercke AM, Wickmann-Hansen G, Eika B. Skills training in laboratory and clerkship: connections, similarities, and differences. [22.01.2014];Med Educ Online. 2003 8:12. doi: 10.3402/meo.v8i.4334. Available from: http://med-ed-online.net/index.php/meo/article/view/4334/4516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McManus IC, Richards P, Winder BC. Clinical experience of UK medical students. Lancet. 1998;351(9105):802–803. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78929-7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78929-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodfellow PB, Claydon P. Students sitting medical finals – ready to be house officers? J R Soc Med. 2001;94(10):516–520. doi: 10.1177/014107680109401007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remes V, Sinisaari I, Harjula A, Helenius I. Emergency procedure skills of graduating medical doctors. Med Teach. 2003;25(2):149–154. doi: 10.1080/014215903100092535. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/014215903100092535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du Boulay C, Medway C. The clinical skills resource: a review of current practice. Med Educ. 1999;33(3):185–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00384.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarikaya O, Civaner M, Kalaca S. The anxieties of medical students related to clinical training. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(11):1414–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.00869.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris MC, Gallagher TK, Ridgway PF. Tools used to assess medical students competence in procedural skills at the end of a primary medical degree: a systematic review. [22.01.2014];Med Educ Online. 2012 17 doi: 10.3402/meo.v17i0.18398. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3427596/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer T, Simmenroth-Nayda A, Herrmann-Lingen C, Wetzel D, Chenot JF, Kleiber C, Staats H, Kochen MM. Medizinische Basisfähigkeiten - ein Unterrichtskonzept im Rahmen der neuen Approbationsordnung. Z Allg Med. 2003;79(9):432–436. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-43063. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-2003-43063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iberer F, Kresse A, Manhal S, Reibnegger G, Toplak H, Krismer M, Mikerevic S, Mutz N, Pierer K, Prodinger W, Vogel W, Kainberger F, Lischka M, Luger A, Mallinger R, Rieder A, Schmidts M, Albegger K, Studnicka M. Österreichischer Kompetenzlevelkatalog für Ärztliche Fertigkeiten. Graz/Innsbruck/Wien/Salzburg: Medizinische Universitäten; 2011. [22.01.2014]. Available from: http://www.meduniwien.ac.at/bemaw/mue/downloads/oekaef.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bürgi H, Rindlisbacher B, Bader C, Bloch R, Bosnan F, Gasser C, Gerke W, Humair JP, Im Hof V, Kaiser H, Lefebvre D, Schläppi P, Sottas B, Spinas GA, Stuck AE. Swiss Catalogue of Learning Objectives for Undergraduate Medical Training. Bern: Universität Bern; 2008. [22.01.2014]. Available from: http://sclo.smifk.ch/sclo2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnabel KP, Boldt PD, Breuer G, Fichtner A, Karsten G, Kujumdshiev S, Schmidts M, Stosch C. Konsensusstatement "Praktische Fertigkeiten im Medizinstudium" – ein Positionspapier des GMA-Ausschusses für praktische Fertigkeiten. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2011;28(4):Doc58. doi: 10.3205/zma000770. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3205/zma000770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Remmen R, Scherpbier A, Van der Vleuten C, Denekens J, Derese A, Hermann I, Hoogenboom R, Kramer A, Van Rossum H, Van Royen P, Bossaert L. Effectiveness of basic clinical skills training programmes: a cross-sectional comparison of four medical schools. Med Educ. 2001;35(2):121–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liddell MJ, Davidson SK, Taub H, Whitecross LE. Evaluation of procedural skills training in an undergraduate curriculum. Med Educ. 2002;36(11):1035–1041. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01306.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.