Abstract

Migration and HIV research in sub-Saharan Africa has focused on HIV risks to male migrants, yet women’s levels of participation in internal migration have met or exceeded those of men in the region. Moreover, studies that have examined HIV risks to female migrants found higher risk behavior and HIV prevalence among migrant compared to non-migrant women. However, little is known about the pathways through which participation in migration leads to higher risk behavior in women. This study aimed to characterize the contexts and processes that may facilitate HIV acquisition and transmission among migrant women in the Kisumu area of Nyanza Province, Kenya. We used qualitative methods, including 6 months of participant observation in women’s common migration destinations and in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted with 15 male and 40 female migrants selected from these destinations. Gendered aspects of the migration process may be linked to the high risks of HIV observed in female migrants— in the circumstances that trigger migration, livelihood strategies available to female migrants, and social features of migration destinations. Migrations were often precipitated by household shocks due to changes in marital status (as when widowhood resulted in disinheritance) and gender-based violence. Many migrants engaged in transactional sex, of varying regularity, from clandestine to overt, to supplement earnings from informal sector trading. Migrant women are at high risk of HIV transmission and acquisition: the circumstances that drove migration may have also increased HIV infection risk at origin; and social contexts in destinations facilitate having multiple sexual partners and engaging in transactional sex. We propose a model for understanding the pathways through which migration contributes to HIV risks in women in high HIV prevalence areas in Africa, highlighting potential opportunities for primary and secondary HIV prevention at origins and destinations, and at key ‘moments of vulnerability’ in the migration process.

Keywords: sub-Saharan Africa, Kenya, gender, HIV, migration, transactional sex

Introduction

Gender is fundamental to understanding migration processes, causes and consequences, and gender and economic inequalities are critical to understanding why the HIV epidemic disproportionately burdens younger, poorer women worldwide. Yet the convergence of these phenomena has been poorly characterized, and is largely absent from the literature on migration and HIV. The central concern of this paper is to shed light on the ways in which gendered migration processes shape the HIV risks faced by female migrants, which in turn helps to explain the persistence of HIV in high prevalence areas.

The feminization of internal migration in Africa

Women’s mobility in sub-Saharan Africa has received little attention in migration studies, in part due to the lack of national-level data for the study of sex-specific patterns and forms of mobility in the region. However, recent studies (Beauchemin & Bocquier, 2004; Beguy et al., 2010; Collinson et al., 2006) have yielded growing evidence for a feminization of internal migration in sub-Saharan Africa; there, as in other developing regions, women’s rates of internal migration have met or exceeded those of men (Bilsborrow, 1992; Zlotnick, 2003). Although there are very few data sources for the study of sex-specific migration trends in Kenya, there is some evidence that a feminization of migration began there at least four decades ago (Thadani, 1982). In the 1970s, while male migrants continued as in previous times to permanently settle in cities, women began increasingly to participate in migration as well, but circulated between predominantly rural areas of economic opportunity (Thadani, 1982). These gendered patterns of migration may be changing: while in the mid 1990s it was estimated that 87 percent of all females and 54 percent of all males resided in rural areas (Agesa & Agesa, 1999), our analysis of 2009 Kenya census data suggest the proportion of females living in rural areas had declined to 68 percent, and of males had risen to 67 percent (National Bureau of Statistics, 2010). This finding is also consistent with prior research documenting the reverse migration in men in Kenya (Francis, 1995), in concert with the male ‘counter-urbanization’ trends observed in Zambia (Potts, 2005) and South Africa (Collinson et al., 2007) since the 1980s.

Reasons for women’s increasing mobility

The factors driving a feminization of internal migration in sub-Saharan Africa are multi-faceted. While men’s migration has been predominantly a labor market response, women’s migration has been more varied and complex (Chant & Radcliffe, 1992; Dodson, 2000; Hugo, 1993). Women’s independent migration has been on the rise, and migration for nuptiality has declined in salience (Bilsborrow, 1992), in tandem with a decline in marriage rates in almost all sub-Saharan African countries after the 1980s (van de Walle & Baker, 2004). In the context of volatile economies and rapid urbanization in the region, women’s increasing mobility is at least in part well-explained by the new economics of labor migration (Massey, 2006; Massey et al., 1998; Stark, 1991): where labor markets are insecure, a geographically stretched household- one in which members live and work in multiple places—also diversifies its risks. Across the region, rising unemployment and steep falls in wages after the 1970s made male migrants’ remittances unreliable and often unsustainable, requiring a renegotiation of gendered rights, responsibilities and power within households undergoing changes in livelihoods, sometimes leading to marital dissolution (Francis, 2002). In Kenya as elsewhere, labor market studies have shown that men have more to gain than do women as a result of rural to urban migration, yet women’s migration persists despite lower returns in earnings in urban destinations (Agesa, 2003). In South Africa, large social transfers (pensions and child support grants) have facilitated the labor migration of working age women (Ardington et al., 2009), and the “sending” of a female migrant has become an essential livelihood strategy that is particularly advantageous to the poorest households (Collinson et al., 2009; Kok et al., 2006). As economic conditions worsened across the region since the 1980s, “traditional” constraints to female migration have relaxed and it has become more acceptable for families to permit their daughters to move (Todes, 1998). Changes in gender norms may also be altering the aspirational aspects of women’s migration; like men, women migrate in search of opportunity and a better standard of living, but some studies have suggested they also leave rural areas to seek autonomy and an escape from the often conservative, patriarchal social norms of rural communities, in pursuit of a modernity characterized by more egalitarian gender relations (Kahn et al., 2003; Le Jeune et al., 2004; Lesclingand, 2004).

The high mortality due to HIV in the region is known to have contributed to household instability and the migration of adults and children (Ford & Hosegood, 2005; Hosegood et al., 2004). HIV/AIDS has also converged in complex ways with other political, environmental and cultural factors to precipitate the disproportionate migration of women in certain settings. In Nyanza Province in western Kenya, the setting for this research, the HIV epidemic has been severe and persistent, with a prevalence rate of 15.4% that was double the national average in 2007 (NACP, 2009). A study in Kisumu, the provincial capital, found that 25% of women and 16% of men were HIV seropositive in 2006 (Cohen et al., 2009). Western Kenya, the homeland of the Luo, has been deeply affected by high mortality due to AIDS. The epidemic has deeply shaped arguments among Luo people about faith and beliefs, engendering a scrutiny of cultural practices (Prince, 2007), especially that of widow guardianship or “inheritance,” in which a widow must sleep with another man in order to “cleanse” the death of her husband and ensure future familial well-being and growth. Among traditionalists, widow inheritance is a sacred practice, ensuring the regeneration of communities (Prince, 2007), and it has also functioned as a means of retaining children within the patrilineage and ensuring the community’s support and protection of widows and surviving children (Potash, 1986). For others, in particular “saved” or “born-again” Christians, widow inheritance is viewed as a “backward” or “heathen” practice that is counter to Christian sensibilities (Prince, 2007), and a major cause of the spread of HIV. Widow inheritance and cleansing continues, though it is controversial locally (Luginaah et al., 2005; Ayikukwei et al., 2008). Our prior research suggested that changing practices and beliefs surrounding widow inheritance may also contribute to female migration from rural areas (Camlin et al., 2013).

The HIV epidemic in western Kenya also converged with a major decline in the formal sector economy since the 1980s, leading to an increased dependence on fishing at Lake Victoria for subsistence, and precipitating a wave of migration to the shoreline from surrounding areas (resulting as well in environmental degradation, declining fish populations, and greater competition for fish) (Mojola, 2011). We have previously documented the predominance of widows among female migrants to the rural beach villages; the fish trade was considered to be “a good business,” requiring minimal training or education, with low start-up costs (roughly equivalent to a local days’ wages) and a consistently high demand for fish (Camlin et al., 2013). Thus, migration to the beaches along Lake Victoria is especially attractive to women recently widowed, or fleeing other forms of strife or shocks to the household, who tend to lack the capital required to start up small-scale trading of other commodities (such as clothing or agricultural products) or other informal sector work (Camlin et al., 2013).

The fish trade along the shores of Lake Victoria is also associated with a sexual economy found in several inland fisheries settings in the region that has been alternatively termed “Fish-for-Sex” (Béné & Merten, 2008; Merten & Haller, 2007) and “Sex for Fish” (Mojola, 2011), or locally, “the jaboya system” (Camlin et al., 2013), in which fishermen grant preferential access to fish to female fish traders whom they select as “customers” in exchange for sex. The terminology “sex-for-fish”, however, belies the complexity of reciprocal benefits of the arrangement for fishermen and traders. Women often initiate, and compete with one another to establish, these relationships with fishermen (Béné & Merten, 2008; Camlin et al., 2013), thereby ensuring a stable access to fish supplies, and greatly reducing the risks and transaction costs of ‘hunting’ for fish in situations where the fish supply is highly uncertain and fishermen are highly mobile (Béné & Merten, 2008). Participation in the jaboya economy is highly controversial and even stigmatized locally because, like widow inheritance, it has been blamed for the spread of HIV (Camlin et al., 2013; Mojola, 2011). However, its persistence as part of the set of livelihood strategies undertaken within lakeshore communities is in part explained by economic and ecological declines in the area. The ecological decline of Lake Victoria, in alignment with the “gendered economy” in Kenya—the gendered structure of the local labor markets, skewed compensation structures and unequal gender power relations—has facilitated women’s participation in transactional sex for subsistence (Mojola, 2011). Our prior research in the setting also suggests that much is at stake for both men and women in the jaboya system. Men’s reports of intense pressure from women to engage in transactional sex (Camlin et al., 2013) complicates gendered narratives in the literature surrounding this phenomenon in which men perpetrate, and women are victims of, the jaboya system at the beaches. We found that independent female migrants to beaches may be especially likely to seek out jaboya relationships, because they are less likely than local women to have the familial or marital relationships with men that would otherwise confer access to fish. Such relationships may also confer social prestige and status to these “outsiders” who otherwise have no formal links to kinship networks within the communities (Camlin et al., 2013).

Female migration and HIV/AIDS

Despite the growing importance of women’s migration in sub-Saharan Africa, the research on migration and HIV in the region has focused on narrow epidemiological concerns, and perhaps as a result, the role of women’s migration in the epidemic has remained obscure. Migration and HIV research in sub-Saharan Africa has tended to focus on HIV risks to male migrants and their partners or migrants overall, often failing to measure the risks to women via their direct involvement in migration (Hunter, 2007, 2010). A closer attention to the role of female migration in the HIV epidemic is overdue. Across the region, the studies which have examined HIV risks to female migrants found higher risk behavior and HIV prevalence in migrant compared to non-migrant women (Abdool Karim et al., 1992; Boerma et al., 2002; Brockerhoff & Biddlecom, 1999; Camlin et al., 2010; Kishamawe et al., 2006; Lydie et al., 2004; Pison et al., 1993; Zuma et al., 2003) and to migrant men (Camlin et al., 2010).

Moreover, in Africa, men’s and women’s mobility patterns differ, with important implications for HIV. Women tend to migrate shorter distances to rural and peri-urban areas, and retain ties to rural homes, while men tend to migrate longer distances to urban areas, returning less frequently (Camlin et al., 2012; Collinson et al., 2006). Because the typical corridors of mobility and destinations differ for males and females in the region, male and female migrants may be exposed to sexual networks and geographic areas with different levels of HIV prevalence, therefore different probabilities of exposure (Morris & Kretzschmar, 1997). Population-based studies have found rates of HIV twice as high in informal settlement/peri-urban areas compared to urban and rural areas (Boerma et al., 2002; Coffee et al., 2005; Shisana et al., 2005). In western Kenya, rural beach villages are key migration destinations for women (Camlin et al., 2013), and the eastern African region’s highest HIV prevalence and incidence rates are found in communities surrounding the lake in Kenya and other countries bordering Lake Victoria (Asiki et al., 2011; Kumogola et al., 2010; Kwena et al., 2010). The migration of women within rural Kenya may have been a critical factor in the diffusion of HIV some two decades ago. Survey research from 1993 documented higher sexual risk behaviors among migrants than non-migrants, and rural women who migrated to other rural areas exhibited higher-risk sexual behavior than did their non-migrant counterparts (Brockerhoff & Biddlecom, 1999). High female mobility may contribute to the sustained high prevalence of HIV in the region, enabling greater inter-connectedness of sexual networks beyond those created by male migrants alone, and thus facilitating the rapid and broad circulation of HIV.

However, questions remain concerning the pathways through which women’s participation in migration would be related to their higher risk sexual behavior. Existing research suggests that both migration and riskier sexual behavior among migrants could be attributed to a psychological ‘predisposition to risk-taking’ (Brockerhoff & Biddlecom, 1999). Riskier sexual behavior among migrants has also been theorized to result from life disruptions such as separation from spouses (Vissers et al., 2008) and exposure to new social environments featuring anonymity and less restrictive sexual norms (Caldwell et al., 1989; Lippman et al., 2007). Migrants having multiple households may foster having multiple “main” lovers—men with whom condom-use is least likely (Brockerhoff & Biddlecom, 1999; Hunter, 2002; Vissers et al., 2008). Structural factors related to gender inequalities in land ownership and inheritance may also influence HIV risks; when African women migrate after losing control over assets upon the dissolution of a marriage or death of a spouse, this may result in their reliance on transactional sex for income (Strickland, 2004). Gender-related inequalities in the labor market influence the range of livelihood strategies available to women and the migration destinations in which they find opportunities to earn income. In southern Africa, women have been more likely than men to migrate to shack/informal settlement areas where they engage in the informal sector work available to them (Hunter, 2007). Both gender inequalities and the “informalization of work” can propel women into a sexual economy (Hunter, 2010) in which migrant women offer sex in exchange for money, commodities, transportation or housing (Desmond et al., 2005; Hunter, 2002) to supplement their low or sporadic earnings.

The literature on transactional sex in Africa has highlighted its distinctions from formal commercial sex work. Elements of patron-client ties and the moral obligation to support the needy, which are fundamental to African social life, distinguish transactional sex from commercial sex work (Swidler & Watkins, 2007). Commercial sex work may be both more socially stigmatized and more spatially-circumscribed within well-known “zones” in communities. Our prior research in the setting suggested that the economic and social instability women experience immediately after migrating may facilitate their uptake of transactional sexual exchanges as an element of their set of livelihood strategies, or their uptake of brothel-based commercial sex work for income (Camlin et al., 2013). As described above, women’s migration to lakeside communities may also lead to their engagement in the “sex-for-fish” economy.

Aims of this research

The central aim of this study was to characterize the social contexts and processes that may facilitate risks of HIV infection among migrant women in a high HIV prevalence area in Kenya. In this paper, we use our findings to propose a model of the pathways through which migration may facilitate HIV acquisition and transmission risks in women, and consider the importance of these findings for crafting more effective HIV prevention efforts in the region.

Methods

We used two qualitative research methods in tandem: 1) six months of participant observation and field notes (Bernard, 1994) in common migration destinations and transit hubs in and near Kisumu, and 2) in-depth semi-structured interviews (Chase, 2008) with 15 male and 40 female migrants selected from these settings using theoretical sampling techniques (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Interviews with men were carried out to explore men’s perspectives on findings that emerged from daily debriefing and preliminary reading of women’s interviews in the same locations. The field research team comprised American and Kenyan Co-Principal Investigators and two research assistants (RAs) from Kisumu who were native speakers of the local languages, with intimate knowledge of the settings for the research. Both were trained in the qualitative data collection methods used for this study.

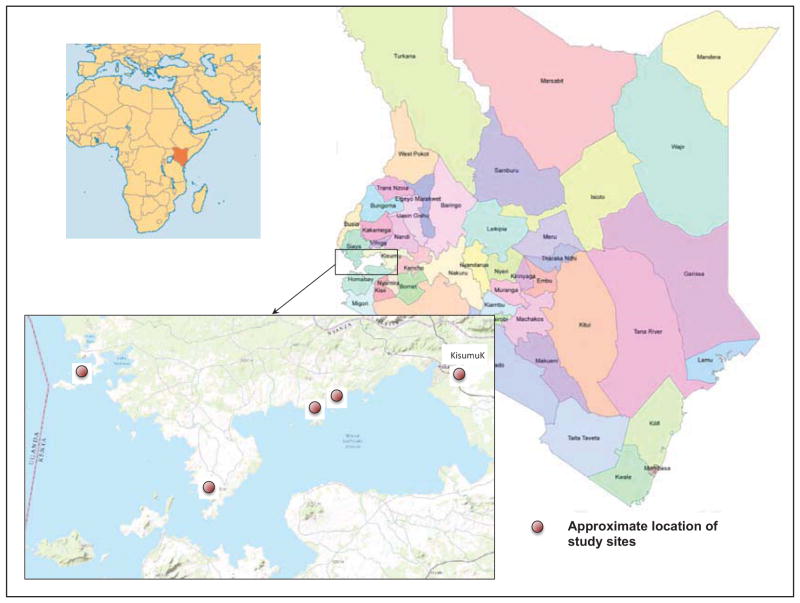

From previous research, we identified potential typologies of female migrants in the area and their main migration destinations. Our preliminary research suggested that in Nyanza Province, Kisumu is a key destination for rural- and urban-to-urban migrants; the beach villages along the shoreline of Lake Victoria are also common destinations for urban- and rural-to-rural migrants. Certain areas of Kisumu also serve as hubs through which highly mobile women transit (e.g. bus stops, market areas and hotels). The research team carried out exploratory visits to these areas in Kisumu and to rural beach villages in several constituencies bordering the lake in Siaya and Kisumu Counties (Bondo, Rarieda, Kisumu East and West), on the basis of the preliminary research, and selected sites for intensive participant observation (Figure 1). The sites also included the largest market in Kisumu (Kibuye, one of the largest markets in East Africa), at which all manner of retail and wholesale goods are purchased for resale at smaller markets in Kisumu, regional markets and beyond. Traders from Uganda, Tanzania and Kenyan towns and cities distant from Kisumu (e.g. Nairobi and Mombasa) also circulate through the market. We selected four rural beach villages in Kisumu and Siaya Counties, including a small, a medium and a large beach village on the mainland and a busy island beach close to the Ugandan border, after obtaining permission from local community leaders, the Chairmen of the Beach Management Unit (a local governance authority), to carry out research at the site. The features of these settings, and the sex-for-fish economy in Nyanza Province, are described in greater detail in another publication from this study (Camlin et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Kenya Counties (2013) and Study Area

Source: Transparency and Government Open Data Initiative, National Information & Communications Technology (ICT) Board, Government of Kenya (https://opendata.go.ke/facet/counties)

We carried out participant observation (Bernard, 1994) in the selected destinations and used theoretical sampling (Strauss & Corbin, 1998) to select participants for in-depth interviews, using typologies of female migration derived from our preliminary research in the setting. The two RAs carried out participant observation in the research sites under the supervision of the two PIs. The RAs prepared field notes focused on their observations of the environment, social actors and relations within the settings, and discussed their observations with the PIs at the end of each day of data collection. Through informal conversations in the research settings during participant observation, the RAs identified individuals eligible for participation in the study, and invited their written informed consent to participate in interviews. In accordance with principles of grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1998), the team continued to sample as the study progressed on the basis of emergent findings and analysis, until theoretical saturation was achieved (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The criteria for selection for participation in interviews were either having participated in at least one adult migration (for women, excluding migration purely for the purpose of nuptiality) or engaging in high levels of mobility. We aimed to capture wide variation in the forms of mobility among women, and therefore used measures that were inclusive of complex, localized mobility. This study defined migration as a permanent change of residence over national, provincial or district boundaries. We defined mobility as a typical pattern of frequent travel away from the area of primary residence for the purpose of business, involving sleeping away at least once per month.

The semi-structured in-depth interview guide for this study adapted the life history approach (Chase, 2008). We asked women to narrate their history of migration and current patterns of movement, reasons for migrations, income-generating activities, positive benefits and negative consequences of migrations, social and sexual relationships, and perceptions and beliefs related to HIV risks. The guide for these interviews included these domains of inquiry yet permitted the exploration of topics not anticipated. Consistent with human subjects research guidelines in Kenya, participants were offered the equivalent of U.S. $4.00 in Kenyan Shillings for participation to reimburse costs of transportation. Recordings of interviews were transcribed verbatim in their native language (either Kiswahili or Luo) and translated into English for analysis using ATLAS.ti (version 6.2.27, Cincom Systems, Berlin, 1993–2011). We analyzed transcripts and field notes and developed a common set of codes describing patterns observed in the data. New codes were defined in relation to existing codes. The study protocol was approved by the University of California at San Francisco Committee on Human Research and the Ethical Review Committee of the Kenya Medical Research Institute prior to the start of data collection. In this article, pseudonyms are used.

Setting

Kisumu is the hub of formal and informal commerce in western Kenya. Situated at the shore of Lake Victoria, it is surrounded by subsistence and commercial farming areas, small towns and villages. District Development Plans have reported high absolute poverty rates (proportions living on less than $1 per day) in the area surrounding Lake Victoria ranging from 53% to 69% (Mojola, 2011). In the results that follow, we describe the circumstances and motivations for women’s migration, the livelihood strategies available to women, and the HIV risks attendant to those strategies in migration destinations. Using these findings, we present a model for understanding HIV risks among female migrants.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Of the overall sample of 40 women, 18 were primarily engaged in the beach-based fish trade. The remaining 22 were engaged in other forms of informal sector work in Kisumu, including Kibuye market vending. Five women whose income is exclusively from commercial sex work were recruited for interviews from sex work venues in Kisumu. Seven of the 15 men interviewed for the study were fishermen and 8 were market traders. The age range of the overall sample was 18 to 58, with an average age of 33 for both male and female participants.

Factors driving female migration

Gender inequities within marriage systems, property rights and livelihoods

In this study, marital dissolution, and the death of a husband, were major driver of women’s migration. After these events, women reported having not been welcome to return to households and families of origin (or if they did so, such stays were typically temporary). Our study did not include women who had been inherited following the death of a husband, were well received and supported by his family, and therefore did not migrate; by definition, those who migrated, the participants in our study, did not fit that category. The widows we interviewed reported either having not wished to stay in the former husband’s homestead, or having not been permitted to stay. Their narratives of experiences with widow inheritance and cleansing, the avoidance of it, or with the denial of their inheritance and property rights, were varied and complex. As mentioned, in exogamous patrilineal marriage systems common throughout sub-Saharan Africa, in which women leave their areas and families of origin to join a husband’s household, women traditionally did not have rights of independent land ownership or property inheritance (FIDA 2008). Retaining widows and their children within the deceased husband’s family and homestead functioned as a social protection to mitigate their structural disadvantage. Yet these traditions, particularly widow inheritance, are in flux and highly contested. Women reported migrating to avoid widow inheritance or cleansing, after humiliating or abusive experiences with inheritors or cleansers, and after in-laws stripped them of land, property and assets, on the pretext that they infected their deceased husbands with HIV. In some instances women were both inherited and also stripped of property and assets. The story of ‘Rose’, a widow aged 36 with three children (and two orphans she supports), exemplifies the hardships many women go through following the death of their husbands:

There was a lot of conflict at home, because after my husband’s death, I was under the care and support of my mother-in-law, [then] the mother-in-law passed away. I was left with my children. I was not working and did not have any other source of income… fights were there, because my mother-in law was the one who was against wife inheritance. Now I was remaining with people who were for it… the conditions were not favorable for my side. When I was told about the job [as an outreach worker for an HIV service organization], I came… I was running away from the conflicts, and I could also support my family.

After her job ended, ‘Rose’ turned to commercial sex work in order to make ends meet:

You know life as a widow is very difficult. You have five children under your care, you have to pay rent, schooling, food and everything… I was a prostitute. I didn’t like the men, I didn’t like the sex, what I liked was the money. I did it from 2007 up to last July [2009]... you know I came here to work, then work was not there. Back at home, there was nobody to support [us] because at my marital place you know in-laws, and the way they react after the death of their brother, nobody was supportive. Back at my parents’ place, both of them are deceased, so I had nowhere to run to. And because of influence from the neighborhood I got myself into it, yes.

Fear of HIV and the blaming of widows for the deaths of their husbands were in many instances invoked as a justification for disinheritance, forcing the migration of women from rural homesteads. As ‘Rose’ told us, “one of my in-laws wanted to cut me with a panga [long knife used for harvesting grain], … they said they must kill me because they felt the death of their brother was caused by me.”

Whether via being denied access to family assets or loss of the husband’s income, widowhood precipitated economic shocks to many rural women’s households, driving them from poverty to destitution. Being reduced to “planting the neighbor’s garden” was emblematic of the lowest depth of poverty following a husband’s death. When women could only cultivate others’ fields as a means of subsistence (and not their own, due to disinheritance) the income and food were not enough to sustain themselves and their children, much less than to also maintain children in school. Women reported migrating from rural areas in order to prevent their children from “becoming street children”. ‘Agnes’ recounted how quarreling with her in-laws compounded the destitution-level poverty she and her children experienced after her husband’s death. In this instance, her late husband’s brother inherited her, and his wife resented the addition of her and her children to their homestead:

I was suffering, digging for people. My brother-in-law, who we remained within the homestead, the wife, had a lot of issues. We never used to agree in that home, … Even when the kids ate in her house she did not like it, …That’s what made me leave, because even my children could not play in the compound.

Other changes in marital status, including divorce and separation, but also additional marriages within polygamous relationships, also precipitated migrations. In some accounts, marital conflicts surrounding polygamy precipitated the dissolution of a relationship. For example, women moved after their husband took a second wife, or were themselves second wives who moved away after conflicts with first wives, or were abandoned when husbands moved away to marry and establish new households. However, we found that even women in stable marital partnerships migrated in order to start businesses when their husbands’ income was inadequate to support the family. Poverty was a stressor that fed marital disputes, and forced the separation of couples, with many women living apart from husbands and visiting periodically:

There were marital problems; we used to squabble. Sometimes when the soap or flour is finished, […] it will force you to go to the man, “please, help us with some money, so that we can go and mill with it.” He started quarreling, saying, “women are running their own businesses out there, but all you do is to look at my face, ‘father so and so, money for buying milling maize!’ Can’t you start a business like other women do?” Then I keep quiet to think. I first tried to sell sugarcane, but it was not enough, because the income was small. (35-year old woman, married with five children)

Gender-based violence

Women also migrated to flee spousal abuse as well as other forms of family violence (including abuse by in-laws), and in some instances experienced multiple episodes of violence, precipitating multiple migrations. ‘Stella’, a widow aged 48, supported six children— three of her own, and three of her deceased co-wife. Her story is exemplary of those for whom polygamy, and intimate partner and family violence were intertwined:

While I was still home with my husband, he got himself another wife. I resisted the idea of accepting another woman, so we fought and he became so violent, the domestic violence was too much for me to handle so I decided to go stay with my sister,… My husband later came for me. I did not know that he was infected with HIV. When my husband and my co-wife died, … my in-laws started grabbing my household items, such as furniture and everything they could lay their hands on. The suitors who wanted to inherit me came one after the other, from my husband’s kinsmen. The more I refused, the more they hardened my life. So I gave in. I stayed with that man for one night and I regret it up to date.

In three instances, women reported migrating in order to protect their children from sexual abuse perpetrated by husbands or inheritors. ‘Makena’, aged 39, divorced her alcoholic husband after she found that he had sexually abused her daughters. She undertook multiple migrations after leaving her husband and being turned away by her in-laws, before finally settling in Kisumu. She supports herself and five children by mixing the sales of second-hand clothing, vegetables and fish, with income from washing bedding for a hotel. She also relies on money given to her regularly by a married man with whom she has a transactional sexual relationship. ‘Mary’, a 32-year old widow with two children, also fled her matrimonial home and migrated to Kisumu when she began to fear that her inheritor was sexually abusing her daughter: “You know, if you get an inheritor, he might separate from the children, … When you leave her behind in the house with the inheritor, he will say that ‘this is not my daughter,’ and then he will rape her.” The convergence of alcoholism with gender-based violence and poverty was a common theme in women’s narratives about the domestic situations from which they fled.

Post-election politically-instigated violence

Violence following Kenya’s national elections in December 2007 spurred several participants to migrate either individually or with their families. The waves of violence drove ethnic minorities from areas in which other ethnic groups were dominant, especially where local political allegiances were closely tied to ethnicity. We interviewed several women who had permanently resettled in their current homes. In several instances of mixed-ethnicity marriages, the post-election violence resulted in the geographic spreading of households, with spouses separated to the lands where they feel they can live safely, commuting for periodic visits to the other spouse, with children often living at the father’s parents’ homestead. In some instances, pre-existing marital conflicts converged with post-election violence to facilitate the separation or dissolution of marital partnerships.

Aspirations

A final theme in women’s narratives of their reasons for migration centered on their aspirations for an improved standard of living, their entrepreneurial drive, and beliefs that migration was necessary in order to achieve their aspirations. In several instances women reported a strong desire to leave villages of origin in order to escape what they characterized as a culture of “jealousy” and conservatism in rural areas. ‘June’, a young trader of second-hand clothing, bitterly recounted her efforts to make a living in her rural village of origin before she migrated to Kisumu: “There is a lot of hatred… Anything you try to do, they spoil, … Their main aim is to take all your items, so as to remain equal.”

Like many other widows, ‘Agnes’ migrated to a beach to start up a fish trade business. Strategically, she still maintained her rural home, however, because she feared that if she did not cultivate her fields there, they would be stolen by her in-laws. And like many other participants in this study, ‘Agnes’ expressed satisfaction that her migration brought about a lessening in her children’s suffering: “My children feed well and they do not [say] ‘So and so’s child had some nice things bought for him… if my father was alive we would be having such and such.’ That makes them not give me such comments all the time.”

Across all of the strategies that women undertake to make ends meet, women’s labor was overwhelmingly driven by the desire to maintain children in school. In 2003, free primary school education was re-introduced by the Kenyan government (Republic of Kenya, 2004) but there are schooling expenses not covered. To obtain money for fees, uniforms, shoes and supplies is not a trivial task for poor households in Kenya as elsewhere in the region, and women living without the support of a husband’s income face particular challenges in earning enough to keep children in school. But perhaps especially for women whose education opportunities were limited, maintaining children in school (or returning them to school, if they were sent home due to non-payment of fees) was highly valued. This was cited as a key benefit of participating in commercial sex work. One participant said, “You know, women can do everything to provide for their children, even the unbelievable things.” Women who were open about their involvement in commercial sex work were adamant that there were few differences between their reasons for migrating and those of other women. ‘Grace’, a 28-year old woman with one child, living off income from commercial sex work, told us:

When my boyfriend left, he left me with a child. There was not any kind of help. I was looking for odd jobs and not getting money, so I decided [to learn] massage [euphemism for commercial sex work]. […] There is no difference- the problems are all the same. If somebody has children and has needs, and the husband has left her, it is a must for her to migrate in search of a better life.

Antecedents to HIV risks

Livelihood strategies available to migrant women

Female migrants in this study diversified their income sources and engaged in a flexible mixture of livelihood strategies, which varied by season, market forces and life circumstances. None of the participants in this study were in the minority of Kenyan women whose higher educational attainment rendered them eligible for the few formal sector employment opportunities available in the Kisumu area. Rather, the women we interviewed engaged in exclusively informal sector work, in small-scale trade (commonly, of clothing and shoes, cosmetics, fish, grains/cereals and vegetables) in markets in Kisumu, regional towns, beaches, and highway crossroads and border crossings. Within a given year, a woman may trade in fish, clothing, and tomatoes when in season, or switch from clothing to fish when fish are in season, or deal in secondhand shoes but supplement with agricultural products to build up capital to buy stock. Women’s patterns of mobility were aligned with seasonal and market-based variations in their livelihood strategies. Women’s trade in a mixture of goods was necessary to ensure a steady income.

“Mixing her business:” Commercial and transactional sex among female traders

Many participants in the study reported engaging in transactional sex and/or commercial sex work in order to supplement their low or sporadic earnings from informal sector work. Women reported a variety of levels of involvement in transactional and/or commercial sex, from clandestine to overt. Some women maintained the social identity of trader and concealed as much as possible their regular commercial sex work on the street, in bars, or in lodgings and hotels, which provided the bulk of their income. Other women were comfortable with a social identity of “commercial sex worker” and carried out their work in well-recognized commercial sex work venues such as brothels and bars. Still others in our study periodically engaged in transactional sex in order to top up income when rent was due, capital was needed to buy stock, or school fees needed to be paid. The practice was common enough that it was referred to with the saying, “she mixes her business.” The following quotations are illustrative of some participants’ discussions of relying on income from transactional, non-romantic sexual relationships as part of their mix of livelihood strategies:

Sometimes you do the Odingi business [work as a fish broker] and you didn’t get money, … and you look at the needs that this money has to cater for, from morning until evening, yet you do not have. Then you think it’s better you go to someone so he can give you. (33 year-old fish trader, living apart from husband, with three children)

There are those who add two to it, [when money is not enough to cover expenses]; sometimes you can even get a certain man to act as the father to the children, … You can be surprised that God gives you that type, he gives you 200 or even 500. (Secondhand clothes trader, aged 34, widowed, with one child)

To be clear, the transactional sexual relationships that these women disclosed to the research team were described in entirely different terms than were the romantic relationships—whether marital or non-marital—that they engaged in. Transactional sexual relationships also differed from the sexual encounters women engaged in within commercial sex venues and settings: in the former case, relationships, while non-romantic, may involve regular contact and endure over time and in the latter case, transactional sexual encounters were once-off and more anonymous.

‘Jane’, aged 29, is single, with one child, and circulates between Kisumu, regional towns and Nairobi to trade in clothing. She told us that her main income was derived from the commercial sex work she engages in when she travels, but that she maintains the “cover” of her identity as a clothes trader in order to avoid the social stigma that accompanies being publicly identified as a sex worker. She does so with a group of other highly mobile traders:

When I leave [the house], most people know I’m going to the market. You know the majority do not know the kind of work that I do, they only know that, … ‘ah, [‘Jane’] was picked up with her friends whom she trades together with.’

Other traders were not as deliberate and organized about their involvement in commercial sex work while traveling for trade, but spoke of transactional sexual relationships as a hazard of the business. One woman told us, “[When you travel], you meet businessmen, who have money. And if you are tempted… you’ll sleep with them. You go to another town, you meet another one.” Another trader said she thought that HIV infection risks to female traders were high, because “you do business, but you do not get enough money. There are those people with money in our midst, but they are men. Because you have seen his money… it becomes easy to get into a relationship with him.”

Compounding the HIV risks that female migrants and highly mobile women face via transactional and/or commercial sex, condom usage is not the norm in the Kisumu area. Many married women who knew of their husbands’ extramarital affairs complained that their husbands refused to use condoms, and commercial sex workers complained that norms against condom use were a distinct drawback of working in the area. While “higher end” sex workers may be paid 200 Kenyan shillings (KSh) (about $2.50) for a single act of intercourse with a condom, they could be paid as much as KSh 1000 (about $12) for sex without a condom. Poorer, less experienced sex workers may earn as little as KSh 50 (about 60 cents) for sex with a condom. ‘Grace’ described the difficulty many women face in insisting on condom use when cash payments are so much higher for unprotected sex:

Men here in Kisumu, almost all of them don’t want to use condoms. If you look at someone, his health is not all that good, … all he sees to be important is money, he doesn’t care about himself or even you… When he refuses to use condom and he is showing you money, what do you think?

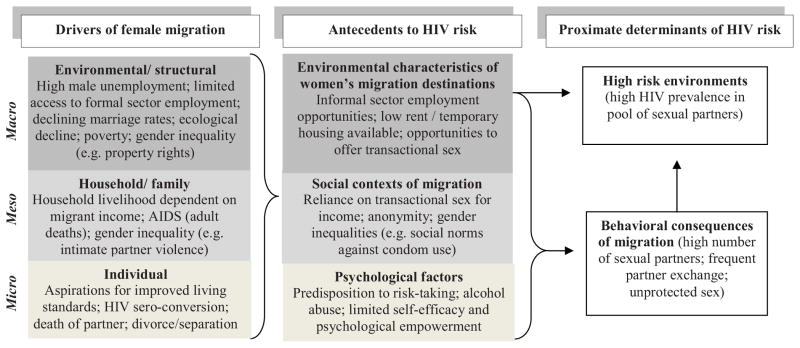

A model for understanding HIV risks among female migrants

Based on these findings and prior research, we have developed a model to guide further research on HIV risks, prevention and treatment needs among female migrants (Figure 2). We suggest that female migrants are at high HIV risk at destination via higher risk sexual behavior, i.e. multiple partnerships and transactional sex, and/or environmental influences in destinations, i.e. exposure to sexual networks in which HIV is highly prevalent. Conversely, many factors that facilitate women’s migration, such as widowhood and gender-based violence, may also facilitate women’s HIV acquisition risk at the point of origin. Thus female migrants may also play a role in the transmission of HIV. We suggest that factors at multiple levels drive the migration of women, and at each level, are structured by gender (social norms, role expectations, and opportunity structures). In turn, a second set of gender-related factors at these levels shape women’s HIV risks in the context of migration. Given the themes examined in this paper, we posit that female migration is driven by:

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework: Factors linking migration to HIV acquisition and transmission risks among women in high HIV prevalence settings in Africa

Environmental/structural factors (macro-level), including political/economic conditions and policies; poverty; ecological decline; declining marriage rates; gender inequalities, including property laws and inheritance practices disadvantageous to women; and HIV, both a consequence and a cause of population mobility.

Household/family factors (meso-level), including events that render households dependent on migrant income (e.g. job losses and deaths of other adults), and HIV. Women may lose income, property and assets following the death of a spouse or be cast out following HIV seroconversion and disclosure. Gender inequalities and economic insecurity facilitate intimate partner violence, which precipitates women’s migration.

Individual factors (micro-level) including those tied to women’s aspirations for improved standard of living, autonomy, and ideals of ‘modernity’ and gender equality; HIV seroconversion; marital formation and dissolution; a ‘pre-disposition to risk-taking’.

We theorize, in turn, that the following three levels of antecedents mutually interact to shape the HIV infection and transmission risks of female migrants:

Characteristics of migration destinations (macro-level). Features of the common destinations of female migrants may directly influence sexual behavior and indirectly influence HIV transmission probabilities. Prevalence has been found to be high in areas that attract female migrants. These areas provide opportunities for informal sector employment and transactional sex, which women may rely upon to supplement low, sporadic informal sector earnings.

Social contexts of migration (meso-level). Reliance on transactional sex due to poverty; anonymity, and freedom from the social monitoring of family members, facilitating transactional sex and the ability to maintain more than one main partnership; ‘negative’ social norms within peer groups (e.g. clandestine commercial sex work among socially affiliated groups of traders) and interpersonal sexual power dynamics that limit women’s ability to negotiate condom use.

Individual factors (micro-level) related to women’s involvement in migration are interrelated with higher-level influences on behavioral risks. A ‘pre-disposition’ to risk-taking (associated with the positive drive to entrepreneurship) may also lead to higher-risk sexual behavior. ‘High HIV risk’ destinations may offer opportunities for non-gender-normative behaviors such as alcohol abuse, facilitating higher risk sexual behavior. In a context of unequal sexual power relations and economic need, women may have limited self-efficacy (for safer sexual behaviors such as condom use) and other elements of psychological empowerment.

Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate why the relationship between HIV and migration among women in high HIV prevalence settings in the region may be bi-directional: at population level, female migrants may be at high risk of transmitting as well as acquiring HIV infection. At origin, migration was often driven by widowhood, divorce/separation, or gender-based violence, resulting in potential exposure to HIV from a spouse or “inheritor,” loss of property and assets, and social vulnerability. At destination, earnings from transactional and/or commercial sex often supplemented women’s low and sporadic earnings from informal sector trading.

Our findings suggest that conventional approaches to defining the category of “labor migrant” in the HIV literature require rethinking. Gender biases in measures of labor force participation have been extensively critiqued, (e.g. Bilsborrow & Secretariat, 1993; Casale & Posel, 2002) yet key lessons learned have not yet carried over to HIV research. For example, in a recent systematic review of the literature on HIV risks to labor migrants (Weine & Kashuba, 2012), studies of female migrants whose income was from commercial sex work were excluded (although few women migrate with the intent to become commercial sex workers, but rather choose the occupation at destination when other livelihood strategies fail), while ironically, “visiting commercial sex workers” was cited as a key HIV risk factor for male migrants, the focus of the review. Our findings suggest a reframing: commercial sex work is an HIV risk factor for female migrants, whose labor has been “more varied in its geography and temporality and tenuous in its legality and security” than that of male migrants (Dodson & Crush, 2004, p. 101).

Our review of literature documenting a rise in women’s participation in internal migration in Kenya and the broader sub-Saharan African region over the past several decades, and of the drivers of this phenomenon, exposed the extent to which women’s migration is inextricably bound with the HIV epidemic that has so burdened the region over the same time period. Yet we found limited theoretical development to help to explain the pathways of influence between the HIV epidemic and women’s migration. Considerations of gender are now well-embedded in migration theories and research, pioneered by studies that drew attention to the male gender bias in the research on migration (Chant & Radcliffe, 1992; Hugo, 1993; Pedraza, 1991; Tienda & Booth, 1991), and leading to research that has highlighted the centrality of gender (across domains such as social norms and role expectations, opportunity structures and social networks) to understanding migration forms, decision-making, determinants and consequences (Curran et al., 2006; De Jong, 2000; Gubhaju & De Jong, 2009). In turn, HIV prevention research has become increasingly concerned with gender relations and the economic contexts of high-risk sexual behaviors (Dworkin & Ehrhardt, 2007; Gupta, 2001). Theories of gender, e.g. Connell’s theory of gender and power (1987), have proved useful for understanding HIV risks. Despite these expanding and complementary theoretical frameworks, no models have emerged to clearly articulate the ways in which the HIV epidemic has influenced gendered patterns of migration, and in turn, how gendered migratory processes shape HIV risks in women and men. The theoretical foundations of the two fields (of gender and migration, and gender and HIV) have remained largely separate.

The present paper was intended to bridge this gap. We have integrated theoretical concepts from research on gender and HIV, and on gender and migration, in order to consider how gendered aspects of migration processes lead to high HIV risks among migrant women. Our model suggests new approaches for understanding the potential pathways linking migration and HIV risks in women, which clearly will need empirical validation in further research. Despite this need, the model shown in Figure 2 provides a framework for understanding pathways through which migration contributes to the HIV epidemic in women in high HIV prevalence areas in Africa. Such a framework serves as a guidepost for potential points of intervention to reduce HIV acquisition and transmission risks among female migrants. The model points to opportunities for primary and secondary HIV prevention efforts at multiple levels, and at both migration origins and destinations. It suggests that a combination of both structural interventions at the macro level (e.g. to address gender inequalities in inheritance laws and practices), and social and psychological interventions at the meso-level (promoting equality in sexual power relations within relationships and gender norms in communities) and micro-level (e.g. improving skills and empowerment in livelihood strategies and sexual relationships) would be needed in order to address the complex interplay of factors that have contributed to elevated risks of HIV in migrant women.

Our model implies that dimensions of temporality and geographic space also should be considered. The high HIV-risk settings in the destinations chosen by women for their livelihood activities (e.g. market areas, low-rent hostels in trading areas, beaches) may be effective sites for interventions and key moments in the migration process may present opportunities for prevention (e.g. following widowhood at origin; upon arrival and at uptake of new livelihood strategies in destinations). Moreover, as promising biomedical interventions to prevent HIV and prolong the lives of those infected continue to emerge, it will be crucial to ensure that highly mobile men and women have full access to these medical technologies and services, and to ensure that those in treatment remain engaged in care despite their mobility. Further research will also be needed to explore how best to amplify the benefits of new biomedical HIV prevention interventions by also addressing the underlying structural factors, such as poverty and gender inequality, that drive the continued spread of HIV.

Conclusion

While it remains under-recognized, women’s mobility may be a major social antecedent to the sustained high levels of HIV prevalence in Nyanza Province, Kenya. It also confers socio-economic benefits to the poorest women and their households in the area. HIV prevention and treatment interventions targeted to migrant and highly mobile women are urgently needed. Such interventions should aim to preserve the positive aspects of mobility for women’s agency, independence and improved socio-economic status, while also reducing the burden of high HIV risks among female migrants.

Research Highlights.

A qualitative study of contextual factors linking mobility & HIV risks in women in western Kenya

Circumstances that drove women’s migration (e.g. widowhood, gender-based violence) may have facilitated HIV acquisition at origin

At destination, many migrants engaged in transactional sex to supplement earnings from informal sector trading

A model of pathways through which mobility facilitates HIV risks in women in Africa is presented

HIV prevention & treatment interventions urgently needed for migrant and highly mobile women in the region

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, University of California San Francisco-Gladstone Institute of Virology & Immunology Center for AIDS Research, P30 AI27763 and the University of California, Berkeley Fogarty International AIDS Training Program (AITRP). Dr. Camlin was supported by a Research Scientist Development Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), K01MH093205. We thank the women and men who participated in this study, Megan Comfort for her helpful advice on methods used in the study, and Lynae Darbes, Sheri Lippman and Nicolas Sheon for their valuable input on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Singh B, Short R, Ngxongo S. Seroprevalence of HIV infection in rural South Africa. AIDS. 1992;6:1535–1539. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199212000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agesa J, Agesa R. Gender differences in the incidence of rural to urban migration: Evidence from Kenya. The Journal of Development Studies. 1999;35:36–58. [Google Scholar]

- Agesa R. Gender Differences in the Urban to Rural Wage Gap and the Prevalence of the Male Migrant. The Journal of Developing Areas. 2003;37:13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ardington C, Case A, Hosegood V. Labor supply responses to large social transfers: Longitudinal evidence from South Africa. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2009;1:22–48. doi: 10.1257/app.1.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asiki G, Mpendo J, Abaasa A, Agaba C, Nanvubya A, Nielsen L, et al. HIV and syphilis prevalence and associated risk factors among fishing communities of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2011;87:511–515. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.046805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchemin C, Bocquier P. Migration and urbanisation in Francophone west Africa: An overview of the recent empirical evidence. Urban Studies. 2004;41:2245–2272. [Google Scholar]

- Beguy D, Bocquier P, Zulu EM. Circular migration patterns and determinants in Nairobi slum settlements. Demographic Research. 2010;23:549–586. [Google Scholar]

- Béné C, Merten S. Women and Fish-for-Sex: Transactional Sex, HIV/AIDS and Gender in African Fisheries. World Development. 2008;36:875–899. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborrow RE. Preliminary Report of the United Nations Expert Group Meeting on the Feminization of Internal Migration. International Migration Review. 1992;26(1):138–161. [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborrow RE, Secretariat UN. Internal female migration and development: an overview. In: Hugo G, editor. Internal Migration of Women in Developing Countries; Proceedings of the United Nations Expert Meeting on the Feminization of Internal Migration; Aguascalientes, Mexico. 22–25 October 1991; New York: United Nations Population Division; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Boerma JT, Urassa M, Nnko S, Ng’weshemi J, Isingo R, Zaba B, et al. Sociodemographic context of the AIDS epidemic in a rural area in Tanzania with a focus on people’s mobility and marriage. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78(Suppl 1):i97–105. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockerhoff M, Biddlecom AE. Migration, Sexual Behavior and the Risk of HIV in Kenya.(Statistical Data Included) International Migration Review. 1999;33(4):833–856. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC, Caldwell P, Quiggin P. Mobility, Migration, Sex, STDs and AIDS: An Essay on Sub-Saharan Africa with Other Parallels. In: Herdt G, editor. Sexual Cultures and Migration in the Era of AIDS. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Camlin CS, Hosegood V, Newell ML, McGrath N, Barnighausen T, Snow RC. Gender, migration and HIV in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camlin CS, Hosegood V, Snow RC. Gendered patterns of migration in South Africa. Population, Space and Place. doi: 10.1002/psp.1794. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camlin CS, Kwena ZA, Dworkin SL. “Jaboya” vs. “jakambi”: Status, negotiation and HIV risk in the “sex-for-fish” economy in Nyanza Province, Kenya. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2013;25(3):216–231. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.3.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casale D, Posel D. The Continued Feminisation of the Labour Force in South Africa: An Analysis of Recent Data and Trends. South African Journal of Economics. 2002;70:156–184. [Google Scholar]

- Chant S, Radcliffe SA. Migration and development: the importance of gender. In: Chant S, editor. Gender and Migration in Developing Countries. New York: Belhaven Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chase SE. Narrative Inquiry: Multiple Lenses, Approaches, Voices. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coffee MP, Garnett GP, Mlilo M, Voeten HA, Chandiwana S, Gregson S. Patterns of movement and risk of HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S159–167. doi: 10.1086/425270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CR, Montandon M, Carrico AW, Shiboski S, Bostrom A, Obure A, et al. Association of attitudes and beliefs towards antiretroviral therapy with HIV-seroprevalence in the general population of Kisumu, Kenya. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinson M, Gerritsen A, Clark S, Kahn K, Tollman S. Migration and socioeconomic change in rural South Africa, 2000–2007. In: Collinson MA, Adazu K, White M, Findley S, editors. The Dynamics of Migration, Health and Livelihoods: INDEPTH Network Perspectives. Surrey, England: Ashgate; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Collinson M, Tollman S, Kahn K. Migration, settlement change and health in post-apartheid South Africa: triangulating health and demographic surveillance with national census data. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2007;69(Supplement):77–84. doi: 10.1080/14034950701356401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collinson M, Tollman S, Kahn K, Clark S, Garenne M. Highly prevalent circular migration: households, mobility and economic status in rural South Africa. In: Tienda M, Findley S, Tollman S, Preston-Whyte E, editors. Africa On the Move: African Migration and Urbanisation in Comparative Perspective. Johannesburg: Wits University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Gender and Power: Society, the Person, and Sexual Politics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Curran SR, Shafer S, Donato KM, Garip F. Mapping Gender and Migration in Sociological Scholarship: Is It Segregation or Integration? International Migration Review. 2006;40:199–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2006.00008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong GF. Expectations, gender, and norms in migration decision-making. Population Studies-a Journal of Demography. 2000;54:307–319. doi: 10.1080/713779089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond N, Allen CF, Clift S, Justine B, Mzugu J, Plummer ML, et al. A typology of groups at risk of HIV/STI in a gold mining town in north-western Tanzania. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:1739–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson B. Women on the move: Gender and cross-border migration to South Africa from Lesotho, Mozambique and Zimbabwe. In: McDonald DA, editor. On Borders: Perspectives on International Migration in Southern Africa. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dodson B, Crush J. a report on gender discrimination in South Africas 2002 Immigration Act: masculinizing the migrant. Feminist Review. 2004;77:96. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin SL, Ehrhardt AA. Going beyond “ABC” to include “GEM”: critical reflections on progress in the HIV/AIDS epidemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:13–18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Hosegood V. AIDS mortality and the mobility of children in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Demography. 2005;42:757–768. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis E. Migration and Changing Divisions of Labour: Gender Relations and Economic Change in Koguta, Western Kenya. Africa. 1995;65:197–215. [Google Scholar]

- Francis E. Gender, migration and multiple livelihoods: cases from Eastern and Southern Africa.(Brief Article) Journal of Development Studies. 2002;38, 167(125) [Google Scholar]

- Gubhaju B, De Jong GF. Individual versus Household Migration Decision Rules: Gender and Marital Status Differences in Intentions to Migrate in South Africa. International Migration. 2009;47:31–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2008.00496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GR. Gender, sexuality and HIV/AIDS: The what, the why and the how. SIECUS Report. 2001;29:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood V, McGrath N, Herbst K, Timaeus IM. The impact of adult mortality on household dissolution and migration in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2004;18:1585–1590. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131360.37210.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugo G. Department of Economic and Social Information and Policy Analysis, editor. Internal Migration of Women in Developing Countries. New York: United Nations; 1993. Migrant women in developing countries. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. The materiality of everyday sex: thinking beyond ‘prostitution’. African Studies. 2002;61:99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. The changing political economy of sex in South Africa: the significance of unemployment and inequalities to the scale of the AIDS pandemic. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. Beyond the male-migrant: South Africa’s long history of health geography and the contemporary AIDS pandemic. Health & Place. 2010;16:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn K, Collinson M, Tollman S, Wolff B, Garenne M, Clark S. Health consequences in migration. Evidence from South Africa’s rural northeast (Agincourt). Conference on African Migration in Comparative Perspective; Johannesburg, South Africa. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kishamawe C, Vissers DC, Urassa M, Isingo R, Mwaluko G, Borsboom GJ, et al. Mobility and HIV in Tanzanian couples: both mobile persons and their partners show increased risk. AIDS. 2006;20:601–608. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000210615.83330.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok P, Gelderblom D, Oucho JO, van Zyl J, editors. Migration in South and Southern Africa: Dynamics and Determinants. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kumogola Y, Slaymaker E, Zaba B, Mngara J, Isingo R, Changalucha J, et al. Trends in HIV & syphilis prevalence and correlates of HIV infection: results from cross-sectional surveys among women attending ante-natal clinics in Northern Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(553) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwena ZA, Bukusi EA, Ng’ayo MO, Buffardi AL, Nguti R, Richardson B, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for sexually transmitted infections in a high-risk occupational group: the case of fishermen along Lake Victoria in Kisumu, Kenya. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2010;21:708–713. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Jeune G, Piche V, Poirier J. Towards a Reconsideration of Female Migration Patterns in Burkina Faso. Canadian Studies in Population. 2004;31:145–177. [Google Scholar]

- Lesclingand M. Nouvelles stratégies migratoires des jeunes femmes rurales au mali: de la valorisation individuelle à une reconnaissance sociale. Sociétés contemporaines. 2004;55:21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lippman SA, Pulerwitz J, Chinaglia M, Hubbard A, Reingold A, Diaz J. Mobility and its liminal context: exploring sexual partnering among truck drivers crossing the Southern Brazilian border. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:2464–2473. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydie N, Robinson NJ, Ferry B, Akam E, De Loenzien M, Abega S. Mobility, sexual behavior, and HIV infection in an urban population in Cameroon. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;35:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. Patterns and Processes of International Migration in the Twenty-First Century: Lessons for South Africa. In: Tienda M, Findley S, Tollman S, Preston-Whyte E, editors. Africa on the Move: African Migration and Urbanisation in Comparative Perspective. Johannesburg: Wits University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Arango A, Koucouci A, Pelligrino A, Taylor JE. Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Merten S, Haller T. Culture, changing livelihoods, and HIV/AIDS discourse: Reframing the institutionalization of fish-for-sex exchange in the Zambian Kafue Flats. Culture Health & Sexuality. 2007;9:69–83. doi: 10.1080/13691050600965968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojola SA. Fishing in dangerous waters: Ecology, gender and economy in HIV risk. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Kretzschmar M. Concurrent partnerships and the spread of HIV. AIDS. 1997;11:641–648. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199705000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS Control Programme, Government of Kenya. Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey, 2007. Nairobi, Kenya: Ministry of Health, Government of Kenya; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics, Government of Kenya. 2009 Kenya Population and Housing Census. Nairobi, Kenya: Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza S. Women and migration: The social consequences of gender. Annual Review of Sociology. 1991;17:303–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.17.080191.001511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pison G, Le Guenno B, Lagarde E, Enel C, Seck C. Seasonal migration: a risk factor for HIV infection in rural Senegal. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1993;6:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potash B. Wives of the Graves: Widows in a Rural Luo Community. In: Potash B, editor. Widows in African Societies: Choices and Constraints. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1986. pp. 44–65. [Google Scholar]

- Potts D. Counter-urbanisation on the Zambian Copperbelt? Interpretations and implications. Urban Studies. 2005;42:583–609. [Google Scholar]

- Prince R. Salvation and Tradition: Configurations of Faith in a Time of Death. Journal of Religion in Africa. 2007;37:84–115. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Kenya. National Action Plan on Education For All (2003–2015) Nairobi: Government Printers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Parker W, Zuma K, Bhana A, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, HIV Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey. Cape Town: Human Science Research Council; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stark O. The Migration of Labour. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Strickland R. TO HAVE AND TO HOLD: Women’s Property and Inheritance Rights in the Context of HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. Working Papers. Washington, D.C: International Center for Research on Women; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Swidler A, Watkins SW. Ties of Dependence: AIDS and Transactional Sex in Rural Malawi. Studies in Family Planning. 2007;38:147–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thadani VN. Social Relations and Geographic Mobility: Male and Female Migration in Kenya. Center for Policy Studies; New York: The Population Council; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Tienda M, Booth K. Gender, Migration and Social-Change. International Sociology. 1991;6:51–72. doi: 10.1177/026858091006001004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todes A. Gender, place, migration and regional policy in South Africa. In: Larsson A, Mapetla M, Schlyter A, editors. Changing Gender Relations in Southern Africa: Issues of Urban Life. Lesotho: The Institute of Southern African Studies and the National University of Lesotho; 1998. pp. 309–330. [Google Scholar]

- van de Walle E, Baker KR. Population Studies Center International Family Change Conference. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2004. The Evolving Culture of Nuptiality in Sub-Saharan Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Vissers DC, Voeten HA, Urassa M, Isingo R, Ndege M, Kumogola Y, et al. Separation of Spouses due to Travel and Living Apart Raises HIV Risk in Tanzanian Couples. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2008;35:714–720. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181723d93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weine SM, Kashuba AB. Labor Migration and HIV Risk: A Systematic Review of the Literature. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(6):1605–1621. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0183-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotnick H. The Global Dimensions of Female Migration. In: Kalia K, editor. Migration Information Source. Washington, D.C: Migration Policy Institute; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zuma K, Gouws E, Williams B, Lurie M. Risk factors for HIV infection among women in Carletonville, South Africa: migration, demography and sexually transmitted diseases. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2003;14:814–817. doi: 10.1258/095646203322556147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]