Abstract

Objective To examine the association between physical activity and risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Design Prospective cohort study.

Setting Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II.

Participants 194 711 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II who provided data on physical activity and other risk factors every two to four years since 1984 in the Nurses’ Health Study and 1989 in the Nurses’ Health Study II and followed up through 2010.

Main outcome measure Incident ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Results During 3 421 972 person years of follow-up, we documented 284 cases of Crohn’s disease and 363 cases of ulcerative colitis. The risk of Crohn’s disease was inversely associated with physical activity (P for trend 0.02). Compared with women in the lowest fifth of physical activity, the multivariate adjusted hazard ratio of Crohn’s disease among women in the highest fifth of physical activity was 0.64 (95% confidence interval 0.44 to 0.94). Active women with at least 27 metabolic equivalent task (MET) hours per week of physical activity had a 44% reduction (hazard ratio 0.56, 95% confidence interval 0.37 to 0.84) in risk of developing Crohn’s disease compared with sedentary women with <3 MET h/wk. Physical activity was not associated with risk of ulcerative colitis (P for trend 0.46). The absolute risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease among women in the highest fifth of physical activity was 8 and 6 events per 100 000 person years compared with 11 and 16 events per 100 000 person years among women in the lowest fifth of physical activity, respectively. Age, smoking, body mass index, and cohort did not significantly modify the association between physical activity and risk of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease (all P for interaction >0.35).

Conclusion In two large prospective cohorts of US women, physical activity was inversely associated with risk of Crohn’s disease but not of ulcerative colitis.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, collectively known as inflammatory bowel disease, are chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract affecting nearly 1.4 million Americans. Inflammatory bowel disease accounts for over $6 bn in direct healthcare costs annually.1 In addition, inflammatory bowel disease is associated with important indirect costs, loss of economic productivity, and work disability.2 3

Although the exact pathophysiology of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis remains largely unknown, findings from ecologic studies,4 the rising incidence in inflammatory bowel disease over the past several decades,5 and the relatively modest risk contribution from known genetic risk loci (<15%),6 highlight the importance of the environment in the development of inflammatory bowel disease. To date, few environmental risk factors have been identified.

Recent in vivo studies have shown that exercise may induce autophagy, a lysosomal degradation pathway known to protect against diseases such as cancer, neurogenerative disorders, infections, and inflammatory disorders.7 In parallel, genome wide association studies have identified susceptibility loci to Crohn’s disease within autophagy pathways, suggesting a possible mechanistic association between physical activity and risk of inflammatory bowel disease.

We examined the association between physical activity and risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in two large ongoing prospective cohort studies of US women, the Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II. With more than 20 years of biennially updated and validated data on lifestyle, diet, and medical diagnoses, these cohorts offered us the unique opportunity to examine the association between physical activity assessed at multiple time points over adulthood and subsequent risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in the context of other potential risk factors.

Methods

Study population

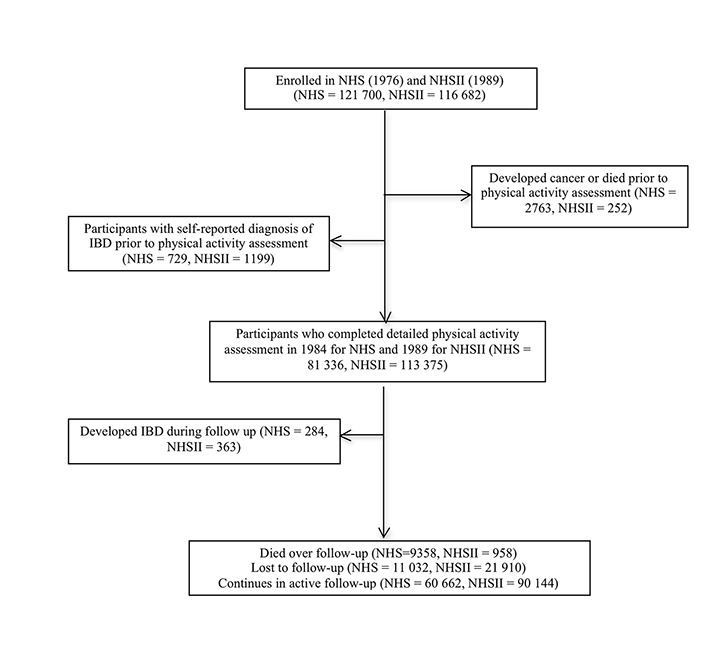

The Nurses’ Health Study is a prospective cohort that began in 1976 when 121 700 US female registered nurses, aged 30 to 55 years, completed a mailed health questionnaire. Follow-up questionnaires are mailed every two years to update health information. In 1989, a parallel cohort, the Nurses’ Health Study II, enrolled 116 686 US female registered nurses between the ages of 25 and 42 years. These women have been followed with similar biennial questionnaires. The figure provides detailed information about the number of participants who were excluded at baseline, were eligible for analyses, and were lost to follow-up.

Flow of eligible participants in study. NHS=Nurses’ Health Study; NHSII=Nurses’ Health Study II; IBD=inflammatory bowel disease

Assessment of physical activity

Starting 1984 in the Nurses’ Health Study and 1989 in the Nurses’ Health Study II, an assessment of physical activity was obtained when participants were asked about their average time per week during the preceding year spent doing any of the following activities: walking or hiking outdoors; jogging; running; bicycling; swimming laps; tennis; calisthenics, aerobics, aerobic dance, or rowing machine; squash or racquet ball; and performing other vigorous activities (for example, mowing the lawn). Participants also reported their usual outdoor walking pace: unable to walk, easy or casual (<2 mph), normal or average (2-2.9 mph), brisk (3-3.9 mph), or very brisk or striding (≥4 mph). These questions were repeated in 1988, 1992, 1996, 1998, 2000, and 2004 in the Nurses’ Health Study and in 1991, 1997, 2001, and 2005 in the Nurses’ Health Study II (see supplementary figure). Each activity was assigned a value for metabolic equivalent task (MET) according to established criteria.8 Each participant’s MET score for walking was assigned on the basis of her reported walking pace. We calculated the MET hours per week (MET h/wk) for each activity by multiplying the MET score by the participant’s reported number of hours of physical activity per week. Total physical activity was computed as the sum of the MET hours per week from all individual activities. Vigorous activity summed the MET hours per week from all the recreational activities listed, excluding walking. All activities included as vigorous had intensity scores of 6 MET or more. To evaluate long term levels of physical activity during the follow-up, we calculated the cumulative average of MET scores for all available physical activity questionnaires prior to diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. We created four variables of updated physical activity, updated vigorous physical activity, cumulative average physical activity, and cumulative average vigorous activity based on data from total physical activity, vigorous physical activity, and cumulative average of total and vigorous physical activity, respectively. When our detailed assessment was not included on biennial questionnaires we carried physical activity data forward from the prior questionnaire cycle (for example, 1988 data used in 1990-92 follow-up). We otherwise did not carry forward missing data. Women with missing data during a questionnaire cycle in which physical activity was assessed did not contribute person years to the analyses.

In a validation study, 151 randomly selected participants from the Nurses’ Health Study II were sent questionnaires on physical activity every three months for a year shortly after they completed the baseline questionnaire.9 The baseline characteristics of these participants, including age, body mass index, and levels of physical activity were similar to that of the entire cohort. The questionnaires contained a recall of activity in the past week to be completed on receipt and an activity diary to be completed daily for the next seven days. At the end of the year, participants were sent a second physical activity questionnaire about the previous year. The correlation for MET hours per week of moderate or vigorous activity was strong (r=0.62), suggesting that the questionnaire is reasonably valid for ranking participants. For walking, the primary activity among the participants in our analysis, the correlation was 0.70. A previous study also found moderate levels of reproducibility during a two year interval (from 1989 through 1991), with a two year test-retest correlation of 0.59.9

Assessment of other covariates

On each biennial questionnaire, women were also asked about pertinent lifestyle factors, including body weight, smoking status, and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hormone therapy, and oral contraceptives. Participants’ self report of body weight, height, and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and oral contraceptives have been previously validated.10 11 In 1992 in the Nurses’ Health Study and in 1991 in the Nurses’ Health Study II, women were also asked their latitude of residence at age 30, which we have previously shown to be associated with risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.12 Information about history of appendicectomy was also collected in 1992 in the Nurses’ Health Study and in 1995 in the Nurses’ Health Study II.

Outcome ascertainment

We have previously detailed our methods for confirming self reported cases of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.12 13 In brief, since 1976 participants have reported diagnoses of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease through an open ended response on biennial surveys. In addition we have specifically queried participants about diagnoses of ulcerative colitis since 1982 and Crohn’s disease since 1992. In the Nurses’ Health Study II we have specifically queried participants about diagnoses of both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease since 1993. When a diagnosis was reported on any biennial questionnaire, two gastroenterologists blinded to exposure information requested and reviewed a supplementary questionnaire and related medical records.

We excluded participants who subsequently denied the diagnosis on the supplementary questionnaire or permission to review their records. Data were extracted on diagnostic tests, histopathology, anatomic location of disease, and disease behavior. Using standardized criteria,14 15 16 17 the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis was based on a typical clinical presentation at four weeks or less and an endoscopic or surgical pathological specimen consistent with ulcerative colitis (for example, evidence of chronicity). The diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was based on a typical clinical history for four weeks or less and endoscopy or radiologic evaluation demonstrating small bowel findings, or surgical findings consistent with Crohn’s disease combined with pathology suggesting transmural inflammation or granuloma. Disagreements were resolved through consensus. Among those women for whom we received adequate medical records, the case confirmation rate for inflammatory bowel disease was 78%.13 Women for whom we did not confirm Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis were included in the analyses as non-cases. After excluding all cases of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis at the baseline questionnaire and among women with missing information on physical activity, we included 284 incident cases of Crohn’s disease and 363 incident cases of ulcerative colitis. These incidence rates are largely consistent with those reported in other US populations.18 19 20

Statistical analysis

Person time for participants was calculated from the date of return of their baseline questionnaires to the date of the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, date of last returned questionnaire, or 1 June 2010 for the Nurses’ Health Study and 1 June 2009 for the Nurses’ Health Study II, whichever came first. At baseline we excluded participants with missing data on physical activity and a history of inflammatory bowel disease or cancer (with the exception of non-melanoma skin cancer). We used Cox proportional hazards modeling with an Anderson-Gill data structure for time varying covariates to adjust for other known or suspected risk factors prior to each two year interval to calculate adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence interval. Because weight may be influenced by preclinical disease, we adjusted for body mass index using the baseline value, consistent with prior analyses.21 We modeled physical activity in fifths or categorically (<3, 3-<9, 9-<18, 18-<27, and ≥27 MET h/wk) consistent with prior studies.22 Categories were chosen to correspond to the equivalent of <1, 1-<3, 3-<6, 6-<9, and ≥9 hours of walking at an average pace per week.

In separate analyses of each study we observed no heterogeneity in the association of physical activity with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis (P for heterogeneity >0.69 for both). Thus we pooled individual level data from each study and adjusted for cohort in all analyses. We evaluated the effect of measurement error in assessing physical activity data on risk of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease using a previously described risk set regression calibration method.23 This analysis was carried out using cumulatively average updated data on physical activity with a general linear measurement error model. We also examined the association between physical activity and risk of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease according to stratums of age, smoking, and body mass index and evaluated these for potential interaction using cross classified categories of these risk factors and physical activity. We tested the significance of interactions by using the log likelihood ratio test comparing the model with cross classified categories with a model that included these factors as independent variables. We used SAS version 9.1.3 for these analyses. All P values were two sided and we considered values <0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

Through 2010 we documented 284 incident cases of Crohn’s disease and 363 incident cases of ulcerative colitis among 194 711 women who contributed 3 421 973 person years of follow-up. Compared with women in the lowest fifth of physical activity, women in the highest fifth were less likely to be obese (body mass index ≥30) or current smokers (table 1). There were no significant differences according to age, history of appendicectomy, and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral contraceptives, or postmenopausal hormone therapy according to fifths of physical activity.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II according to fifths of physical activity*. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | Physical activity (MET h/wk) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest fifth (n=38 117) | 2nd fifth (n=39 119) | 3rd fifth (n=39 346) | 4th fifth (n=39 182) | Highest fifth (n=38 947) | |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 42.4 (10.6) | 42.3 (10.8) | 42.2 (10.9) | 42.2 (11.0) | 41.8 (11.3) |

| Geographical latitude at age 30: | |||||

| Southern | 5811 (15.2) | 5335 (13.6) | 5606 (14.3) | 5466 (14.0) | 5358 (13.8) |

| Middle | 14 913 (39.1) | 15 831 (40.5) | 15 823 (40.2) | 15 587 (39.8) | 14 773 (37.9) |

| Northern | 10 318 (27.1) | 11 217 (28.7) | 11 313 (28.8) | 11 600 (29.6) | 11 456 (29.4) |

| Foreign/unknown | 7075 (18.6) | 6736 (17.2) | 6604 (16.8) | 6529 (16.7) | 7360 (18.9) |

| Baseline body mass index: | |||||

| <20 | 4198 (11.0) | 4282 (11.0) | 4443 (11.3) | 4808 (12.3) | 5926 (15.2) |

| 20-24.9 | 17 123 (44.9) | 19 107 (48.8) | 20 644 (52.5) | 21 794 (55.6) | 22 302 (57.3) |

| 25-29.9 | 9567 (25.1) | 9827 (25.1) | 9513 (24.2) | 8896 (22.7) | 7685 (19.7) |

| ≥30 | 7229 (19.0) | 5903 (15.1) | 4746 (12.0) | 3684 (9.4) | 3034 (7.8) |

| Smoking: | |||||

| Never | 20 821 (54.6) | 22 219 (56.8) | 22 602 (57.4) | 22 432 (57.2) | 21 809 (56.0) |

| Former | 9368 (24.6) | 9762 (25.0) | 10 640 (27.1) | 11 195 (28.6) | 11 527 (29.6) |

| Current | 7928 (20.8) | 7138 (18.3) | 6104 (15.5) | 5555 (14.2) | 5615 (14.4) |

| Regular use of ≥2 tablets/wk NSAIDs | 4994 (13.1) | 5028 (12.9) | 4904 (12.5) | 4977 (12.7) | 4968 (12.8) |

| Ever use of oral contraceptives | 25 976 (68.2) | 26 610 (68.0) | 26 932 (68.5) | 26 852 (68.5) | 26 535 (68.1) |

| Postmenopause | 11 513 (30.2) | 11 787 (30.1) | 11 905 (30.3) | 11 888 (30.3) | 11 882 (30.5) |

| Postmenopausal hormone use†: | |||||

| Never | 6126 (53.2) | 6129 (52.0) | 5918 (49.7) | 5781 (48.6) | 5885 (49.5) |

| Former | 2494 (21.7) | 2534 (21.5) | 2571 (21.6) | 2624 (22.1) | 2461 (20.7) |

| Current | 2893 (25.1) | 3124 (26.5) | 3416 (28.7) | 3483 (29.3) | 3536 (29.8) |

| History of appendicectomy | 6716 (17.6) | 6906 (17.7) | 6999 (17.8) | 6879 (17.6) | 6627 (17.0) |

MET h/wk=metabolic equivalent task hours per week.

*Values are standardized to age distribution of study population. All variables are derived from baseline questionnaires (1986 in Nurses Health Study and 1989 in Nurses Health Study II) with exception of geographic location (1992 and 1993, respectively), oral contraceptive use (1984 and baseline, respectively), and appendicectomy (baseline and 1995, respectively).

†Percentages among postmenopausal women.

Compared with women in the lowest fifth of overall physical activity, the age adjusted risk of Crohn’s disease decreased with increasing level of physical activity (table 2). The risk was not significantly altered after adjusting for known and potential risk factors for Crohn’s disease, including body mass index, smoking, appendicectomy, and use of oral contraceptives, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and postmenopausal hormone therapy (P for trend 0.02). Compared with women in the lowest fifth of physical activity, the multivariate adjusted hazard ratio of Crohn’s disease was 0.74 (95% confidence interval 0.52 to 1.05) for the second fifth of physical activity, 0.88 (0.63 to 1.24) for the third fifth, 0.65 (0.45 to 0.95) for the fourth fifth, and 0.64 (0.44 to 0.94) for the highest fifth.

Table 2.

Physical activity and risk of Crohn’s disease in Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II (1984-2010)

| Variables | Physical activity fifth | P for trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | Highest | ||

| Updated physical activity*: | ||||||

| Median (SD) MET h/wk | 1.0 (1.0) | 5.1 (1.8) | 11.2 (2.9) | 21.5 (5.0) | 45.2 (33.2) | |

| No of cases | 72 | 54 | 63 | 48 | 47 | |

| Person years | 667 291 | 684 398 | 689 222 | 692 548 | 688 514 | |

| Age adjusted (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.71 (0.50 to 1.02) | 0.83 (0.59 to 1.17) | 0.61 (0.42 to 0.88) | 0.60 (0.42 to 0.87) | 0.005 |

| Multivariable adjusted (95% CI)† | 1.00 | 0.74 (0.52 to 1.05) | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.24) | 0.65 (0.45 to 0.95) | 0.64 (0.44 to 0.94) | 0.02 |

| Cumulative average physical activity (MET h/wk): | ||||||

| Median (SD) MET h/wk | 2.6 (1.5) | 7.2 (2.1) | 13.0 (3.1) | 21.6 (5.0) | 41.4 (29.9) | |

| No of cases | 59 | 66 | 63 | 50 | 46 | |

| Person years | 601 262 | 694 609 | 720 478 | 724 306 | 681 317 | |

| Age adjusted (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.67 to 1.35) | 0.88 (0.62 to 1.25) | 0.67 (0.46 to 0.98) | 0.65 (0.44 to 0.95) | 0.005 |

| Multivariable adjusted (95% CI)† | 1.00 | 0.98 (0.69 to 1.40) | 0.92 (0.64 to 1.32) | 0.71 (0.47 to 1.03) | 0.68 (0.46 to 1.01) | 0.01 |

| Updated vigorous physical activity‡ (MET h/wk): | ||||||

| Median (SD) MET h/wk | 0 (0.02) | 0.5 (1.0) | 4.5 (2.4) | 8.8 (5.1) | 28.5 (29.8) | |

| No of cases | 54 | 78 | 52 | 58 | 42 | |

| Person years | 560 547 | 942 886 | 532 859 | 702 710 | 682 970 | |

| Age adjusted (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.61 to 1.40) | 1.01 (0.68 to 1.50) | 0.90 (0.61 to 1.33) | 0.64 (0.42 to 0.98) | 0.05 |

| Multivariable adjusted (95% CI)† | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.61 to 1.40) | 1.04 (0.70 to 1.53) | 0.92 (0.62 to 1.37) | 0.66 (0.43 to 1.02) | 0.09 |

| Cumulative average vigorous physical activity (MET h/wk): | ||||||

| Median (SD) MET h/wk | 0 (1.0) | 0.5 (2.7) | 3.7 (5.2) | 7.4 (8.9) | 21.0 (30.8) | |

| No of cases | 53 | 69 | 67 | 49 | 46 | |

| Person years | 517 491 | 829 798 | 668 005 | 725 927 | 680 753 | |

| Age adjusted (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.84 (0.58 to 1.22) | 0.95 (0.66 to 1.36) | 0.66 (0.44 to 0.98) | 0.63 (0.42 to 0.94) | 0.01 |

| Multivariable adjusted (95% CI)† | 1.00 | 0.84 (0.57 to 1.21) | 0.96 (0.66 to 1.38) | 0.67 (0.45 to 0.99) | 0.65 (0.42 to 0.97) | 0.02 |

MET h/wk=metabolic equivalent task hours per week.

*Mean of physical activity over follow-up.

†Models adjusted for age (months), smoking (never, former, current), body mass index at baseline (<20, 20-24.9, 25-29.9, ≥30), oral contraceptive use (never, former, current), hormone therapy (never, former, current, premenopause), appendicectomy (no, yes), geographic latitude of residence at age 30 (southern, middle, northern, missing/unknown), cohort (National Nurses’ study, National Nurses’ Study II), and non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug use (<2 tablets/week, ≥2 tablets/week).

‡Defined as jogging, running, biking, swimming, tennis, aerobics, and other vigorous exercises.

According to prespecified categories of activity, the risk of Crohn’s disease decreased with increasing levels of physical activity (P for trend 0.007). Compared with women in the lowest category of physical activity (<3 MET h/wk), the multivariate adjusted hazard ratio of Crohn’s disease was 0.65 (95% confidence interval 0.44 to 0.95) among those in the 3-<9 MET h/wk category, 0.73 (0.51 to 1.06) in the 9-<18 MET h/wk category, 0.48 (0.30 to 0.75) in the 18-<27 MET h/wk category, and 0.56 (0.37 to 0.84) in the ≥27 MET h/wk category. We estimated that each 10 MET h/wk (equivalent to approximately 2.5 hours of brisk walking per week) increase in physical activity was associated with a 6% reduction in risk of Crohn’s disease (hazard ratio 0.94, 95% confidence interval 0.87 to 1.00). After correcting for measurement error, we observed a larger, albeit non-statistically significant effect estimate (hazard ratio 0.83, 95% confidence interval 0.63 to 1.11).

In analyses in which we considered only the baseline report of physical activity (1986 in the Nurses’ Health Study and 1989 in the Nurses’ Health Study II), we observed a similar trend with lower risk of Crohn’s disease (P for trend 0.03). To evaluate the effect of long term physical activity, we examined the cumulative average of physical activity data in relation to risk of Crohn’s disease and observed similar associations (P for trend 0.01, table 2). Compared with women in the lowest fifth of cumulative physical activity, the multivariate adjusted hazard ratio of Crohn’s disease among women in the highest fifth of cumulative physical activity was 0.68 (95% confidence interval 0.46 to 1.01).

As walking accounted for the majority of physical activity among the participants, we considered the specific effect of vigorous physical activity, consisting of jogging, running, biking, swimming, tennis, aerobics, and other vigorous exercises, on risk of Crohn’s disease (table 2). Compared with women in the lowest fifth of vigorous physical activity, women in the highest fifth had a multivariate adjusted hazard ratio of 0.66 (95% confidence interval 0.43 to 1.02, P for trend 0.09). Similarly, compared with women in the lowest fifth of cumulative average of vigorous physical activity, women in the highest fifth had a multivariate adjusted hazard ratio of 0.63 (0.42 to 0.95, P for trend 0.02).

We explored the possibility that prediagnosis symptoms of Crohn’s disease may have limited physical activity and therefore may account for our observed inverse association. Thus we performed lag analyses using physical activity data collected at least four years prior to each two year follow-up interval and observed similar associations. Compared with women in the lowest fifth of cumulative average of physical activity, women in the highest fifth had a multivariate adjusted hazard ratio of 0.71 (0.46 to 1.09, P for trend 0.03). Similarly, compared with women in the lowest fifth of cumulative average of vigorous physical activity, women in the highest fifth had a multivariate adjusted hazard ratio of 0.68 (0.43 to 1.06, P for trend 0.02).

In contrast to Crohn’s disease, we did not observe an association between physical activity and risk of ulcerative colitis (table 3). Compared with women in the lowest fifth of overall physical activity, the multivariate adjusted hazard ratio of ulcerative colitis among women in highest fifth of physical activity was 0.91 (95% confidence interval 0.65 to 1.26). We also did not observe any association between physical activity and ulcerative colitis according to prespecified categories (<3, 3 -<9, 9-< 18, 18-< 27, ≥27 MET h/wk) (P for trend 0.42). Similarly, there was no association between cumulative average of physical activity and risk of ulcerative colitis. Compared with women in the lowest fifth of physical activity, women in the highest fifth had a multivariate adjusted hazard ratio of 0.93 (95% confidence interval 0.66 to 1.30). We also did not observe an association between updated (P for trend 0.49) and cumulative average (P for trend 0.40) assessments of vigorous physical activity and risk of ulcerative colitis (table 3).

Table 3.

Physical activity and risk of ulcerative colitis in Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II (1984-2010)

| Variables | Physical activity fifth | P for trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | Highest | ||

| Updated physical activity* (MET h/wk): | ||||||

| Median (SD) MET h/wk | 1.0 (1.0) | 5.1 (1.8) | 11.2 (2.9) | 21.5 (5.0) | 45.2 (33.2) | |

| No of cases | 74 | 67 | 85 | 63 | 74 | |

| Person years | 667 291 | 684 398 | 689 222 | 692 548 | 688 514 | |

| Age adjusted (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.23) | 1.10 (0.80 to 1.51) | 0.82 (0.58 to 1.15) | 0.96 (0.70 to 1.33) | 0.70 |

| Multivariable adjusted (95% CI)† | 1.00 | 0.87 (0.62 to 1.21) | 1.06 (0.78 to 1.46) | 0.78 (0.56 to 1.10) | 0.91 (0.65 to 1.26) | 0.46 |

| Cumulative average physical activity (MET h/wk): | ||||||

| Median (SD) MET h/wk | 2.6 (1.5) | 7.2 (2.1) | 13.0 (3.1) | 21.6 (5.0) | 41.4 (29.9) | |

| No of cases | 67 | 72 | 80 | 71 | 73 | |

| Person years | 601 262 | 694 609 | 720 478 | 724 306 | 681 317 | |

| Age adjusted (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.94 (0.68 to 1.32) | 1.02 (0.73 to 1.41) | 0.89 (0.64 to 1.25) | 0.99 (0.71 to 1.38) | 0.83 |

| Multivariable adjusted (95% CI)† | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.66 to 1.29) | 0.98 (0.71 to 1.36) | 0.85 (0.61 to 1.20) | 0.93 (0.66 to 1.30) | 0.56 |

| Updated vigorous physical activity‡ (MET h/wk): | ||||||

| Median (SD) MET h/wk | 0 (0.02) | 0.5 (1.0) | 4.5 (2.4) | 8.8 (5.1) | 28.5 (29.8) | |

| No of cases | 68 | 90 | 59 | 79 | 67 | |

| Person years | 560 547 | 942 886 | 532 859 | 702 710 | 682 970 | |

| Age adjusted (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.69 to 1.42) | 0.90 (0.63 to 1.29) | 1.01 (0.74 to 1.44) | 0.90 (0.64 to 1.28) | 0.64 |

| Multivariable adjusted (95% CI)† | 1.00 | 0.99 (0.69 to 1.42) | 0.90 (0.63 to 1.29) | 1.01 (0.72 to 1.41) | 0.87 (0.61 to 1.23) | 0.49 |

| Cumulative average vigorous physical activity (MET h/wk): | ||||||

| Median (SD) MET h/wk | 0 (1.0) | 0.5 (2.7) | 3.7 (5.2) | 7.4 (8.9) | 21.0 (30.8) | |

| No of cases | 68 | 71 | 86 | 66 | 72 | |

| Person years | 517 491 | 829 798 | 668 005 | 725 927 | 680 753 | |

| Age adjusted (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.75 (0.53 to 1.05) | 1.04 (0.76 to 1.44) | 0.76 (0.54 to 1.07) | 0.88 (0.63 to 1.22) | 0.57 |

| Multivariable adjusted (95% CI)† | 1.00 | 0.74 (0.52 to 1.04) | 1.02 (0.74 to 1.41) | 0.73 (0.52 to 1.03) | 0.84 (0.60 to 1.18) | 0.40 |

MET h/wk=metabolic equivalent task hours per week.

*Mean of physical activity over follow-up.

†Models adjusted for age (months), smoking (never, former, current), body mass index at baseline (<20, 20-24.9, 25-29.9, ≥30), oral contraceptive use (never, former, current), hormone therapy (never, former, current, premenopause), appendicectomy (no, yes), geographic latitude of residence at age 30 (southern, middle, northern, missing/unknown), cohort (National Nurses’ study, National Nurses’ Study II), and non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug use (<2 tablets/week, ≥2 tablets/week).

‡Defined as jogging, running, biking, swimming, tennis, aerobics, and other vigorous exercises.

Finally, as body mass index, age, and smoking may modify the effect of physical activity on risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, we examined associations according to stratums defined by these variables. The association of physical activity with either Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis was not modified by age (≤40, >40), body mass index (<25, ≥25), and smoking (never, ever) (all P for interaction >0.35).

Discussion

In two large prospective cohorts of US women, physical activity was associated with a lower risk of Crohn’s disease but not of ulcerative colitis. These results were consistent even after accounting for known and possible risk factors for Crohn’s disease, including smoking and body mass index. We observed that women who engaged in physical activity of more than 27 metabolic equivalent task (MET) hours per week, or the equivalent of more than nine hours per week of walking at an average pace, had a 44% lower risk of developing Crohn’s disease compared with women who were inactive (<3 MET h/wk). This risk relative reduction translated into a change in incidence rate of 11 cases per 100 000 person years among women in the highest category of physical acitivty to 7 cases per 100 000 person years among those in the lower category of physical activity.

Comparison with other studies

Our findings are consistent with findings from two prior case-control studies.24 25 The first of these studies,24 using occupation as a proxy for physical activity, described an inverse correlation between occupations involving exercise and risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. The other study25 used a single mailed questionnaire to obtain data on physical activity from cases and controls and observed an inverse association between regular physical activity and risk of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. Because these case-control studies had limited ascertainment of physical activity as well as other lifestyle factors, our cohort analysis, with detailed and updated information on activity and other known or putative risk factors for Crohn’s disease, significantly extends these findings. Our results, however, contrast with those of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort, which failed to observe a relation between physical activity and risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.26 However, this study included only 67 cases of Crohn’s disease and was unable to account for changes in physical activity and body mass index over long term follow-up.

Although our understanding of the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease remains incomplete, the discovery of distinct genetic susceptibility loci for both diseases points to potential diverging biological pathways.27 28 Most notably, genome-wide association studies have identified several distinct candidate genes for Crohn’s disease (for example, ATG16L1, IRGM) primarily involved in the regulation of autophagy. Recent observations that physical activity might induce autophagy may therefore explain the unique association between physical activity and risk of Crohn’s disease.7 In addition, previous physiologic and in vitro studies suggest a role for physical activity in reducing chronic inflammation and regulating innate immunity.29

Strengths and limitations of this study

Our study has several notable strengths. Firstly, our prospective study design avoids the potential recall and selection biases of retrospective, case-control studies that collect data on lifestyle after diagnosis of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. Secondly, we confirmed all cases of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis through a review of medical records, a significant advantage over studies that rely on self report or discharge codes, which may not accurately reflect true diagnoses. Thirdly, the availability of detailed and validated information on body mass index, prior oral contraceptive use, and smoking allowed us to control for several potential risk factors that may have influenced our observed associations. Fourthly, in our analysis we collected information on physical activity every two to four years and used time varying exposures in our Cox models. Thus we were able to account for changes in participants’ physical activity level over time, minimizing the possibility of exposure misclassification. Lastly, our validation study9 demonstrated that our participants self reported physical activity is relatively valid and reproducible.

We acknowledge several limitations. Firstly, our cohort may not be representative of the overall US population. However, as we have previously reported,12 our age specific incidence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are largely similar to rates from other US populations. In addition, previous studies have shown that the prevalence of risk factors, such as smoking and body mass index, in our cohort are consistent with those of the broader population of US women.30 31 Secondly, despite our high follow-up rate over 20 years and participants’ health literacy as nurses, it is possible that some cases of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease were not reported. However, such misclassification of the outcome would tend to attenuate our risk estimates towards the null. Thirdly, we acknowledge that our observed association may have been influenced by measurement bias or inaccuracies arising from self reported measures of physical activity. However, we observed consistent associations between physical activity and risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis across different subgroups of body mass index and smoking. In addition, adjusting for measurement errors did not significantly alter our observed risk estimates. Fourthly, we acknowledge that the mean age at diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in our cohorts is older than the age at diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in the general population. However, as we have previously shown,12 13 32 the distribution of known risk factors (for example, smoking and use of oral contraceptives), anatomic location, and disease behavior among women with inflammatory bowel disease in our cohorts is similar to other population based cohorts. These findings suggest that our results will likely have relevance to the greater population of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. None the less, further studies are needed to examine the association of physical activity with the incidence of Crohn’s disease with onset at younger ages. Fifthly, our study is observational and we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding. However, adjustment for the most important risk factors previously identified for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease did not appreciably alter our results. Lastly, we acknowledge that there could be significant between person heterogeneity in the calculation of energy expenditure from physical activity based on factors such as levels of fitness, body size, as well as various environmental factors such as latitude, external temperature, and humidity. These factors may affect the accuracy of MET hours per week values as a reflection of energy expenditure. However, since such biases are non-differential, it would bias our results towards the null and therefore could potentially further strengthen our observed associations.

Conclusion

In two large prospective cohorts of US women, increased physical activity was associated with a lower risk of Crohn’s disease but not of ulcerative colitis. Whether these associations with disease incidence may imply a benefit of physical activity on disease activity in patients with existing Crohn’s disease is unclear and merits further study. In addition, further studies on the effect of physical activity on risk and progression of Crohn’s disease in the context of known genetic risk factors in autophagy and innate immunity pathways will help elucidate the mechanism underlying this association. Ultimately, this may lead to lifestyle interventions among subgroups with known genetic risk factors for Crohn’s disease to modify the risk of disease or among patients with established disease to limit its progression.

What is already known on this topic

Few studies have explored the association between physical activity and risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

Many previous studies have limited information on physical activity and lifestyle factors that can influence or modify this association

What this study adds

Our data show that increased physical activity is associated with a lower risk of Crohn’s disease but not of ulcerative colitis

Taken together with previous observations that physical activity may induce autophagy and modulate innate immunity, our findings suggest that such pathways may play a stronger role in the cause of Crohn’s disease compared with ulcerative colitis

Contributors: HK conceived and designed the study; acquired the data; carried out the statistical analysis; interpreted the data; and drafted the manuscript. He is guarantor. ANA, GK, and CSF acquired the data and critically revised the manuscript. XL and DS analysed and interpreted the data and critically revised the manuscript. LMH acquired the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. JMR conceived and designed the study; acquired the data; and critically revised the manuscript. JRK conceived and designed the study and critically revised the manuscript. ATC conceived and designed the study; analysed and interpreted the data; drafted the manuscript; and critically revised the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by National Institute of Health grants: R01 CA137178, R01 CA050385, P01 CA87969, P30 DK043351, K23 DK099681, K08 DK064256, K24 098311, and K23 DK091742. ATC is a Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation clinical investigator. HK is supported by a career development award from the American Gastroenterological Association and by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K23 DK099681). LMH is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K08 DK064256). ANA is a member of the scientific advisory board for Prometheus and Janssen. JMR is a consultant for policy analysis. ATC has served as a consultant for Bayer Healthcare, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Pozen.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the institutional review board at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Data sharing: Data, the statistical code, questionnaires, and technical processes are available from the corresponding author at achan@partners.org.

Transparency: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) on behalf of all authors affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;347:f6633

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Timing of ascertainment of exposures and outcomes

References

- 1.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, Ollendorf DA, Sandler RS, Galanko JA, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1907-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Longobardi T, Jacobs P, Bernstein CN. Work losses related to inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: results from the National Health Interview Survey. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1064-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sewell GW, Rahman FZ, Levine AP, Jostins L, Smith PJ, Walker AP, et al. Defective tumor necrosis factor release from Crohn’s disease macrophages in response to Toll-like receptor activation: relationship to phenotype and genome-wide association susceptibility loci. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012;18:2120-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsironi E, Feakins RM, Probert CS, Rampton DS, Phil D. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease is rising and abdominal tuberculosis is falling in Bangladeshis in East London, United Kingdom. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1749-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46-54 e42; quiz e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2012;491:119-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He C, Bassik MC, Moresi V, Sun K, Wei Y, Zou Z, et al. Exercise-induced BCL2-regulated autophagy is required for muscle glucose homeostasis. Nature 2012;481:511-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs DR Jr, Montoye HJ, Sallis JF, et al. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993;25:71-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf AM, Hunter DJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Corsano KA, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a self-administered physical activity questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol 1994;23:991-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Chasan-Taber L, Troy L, Stampfer MJ, et al. Reproducibility of oral contraceptive histories and validity of hormone composition reported in a cohort of US women. Contraception 1997;56:373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Troy LM, Hunter DJ, Manson JE, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. The validity of recalled weight among younger women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1995;19:570-2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khalili H, Huang ES, Ananthakrishnan AN, Higuchi L, Richter JM, Fuchs CS, et al. Geographical variation and incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among US women. Gut 2012;61:1686-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khalili H, Higuchi LM, Ananthakrishnan AN, Richter JM, Feskanich D, Fuchs CS, et al. Oral contraceptives, reproductive factors and risk of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2013;62:1153-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loftus EV Jr, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology 1998;114:1161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loftus EV Jr, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gut 2000;46:336-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fonager K, Sorensen HT, Rasmussen SN, Moller-Petersen J, Vyberg M. Assessment of the diagnoses of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a Danish hospital information system. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996;31:154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moum B, Vatn MH, Ekbom A, Fausa O, Aadland E, Lygren I, et al. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in southeastern Norway: evaluation of methods after 1 year of registration. Southeastern Norway IBD Study Group of Gastroenterologists. Digestion 1995;56:377-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Lewis JD, Griffin PM, Allison J. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in a Northern California managed care organization, 1996-2002. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1998-2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loftus CG, Loftus EV Jr, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Tremaine WJ, Melton LJ 3rd, et al. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940-2000. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:254-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalili H, Huang ES, Ananthakrishnan AN, Higuchi L, Richter JM, Fuchs CS, et al. Geographical variation and incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among US women. Gut 2012;61:1686-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu FB, Willett WC, Li T, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Manson JE. Adiposity as compared with physical activity in predicting mortality among women. N Engl J M 2004;351:2694-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eliassen AH, Hankinson SE, Rosner B, Holmes MD, Willett WC. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer among postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1758-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liao X, Zucker DM, Li Y, Spiegelman D. Survival analysis with error-prone time-varying covariates: a risk set calibration approach. Biometrics 2011;67:50-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sonnenberg A. Occupational distribution of inflammatory bowel disease among German employees. Gut 1990;31:1037-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Persson PG, Leijonmarck CE, Bernell O, Hellers G, Ahlbom A. Risk indicators for inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Epidemiol 1993;22:268-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan SS, Luben R, Olsen A, Tjonneland A, Kaaks R, Teucher B, et al. Body mass index and the risk for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: data from a European prospective cohort study (The IBD in EPIC Study). Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:575-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2066-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lees CW, Barrett JC, Parkes M, Satsangi J. New IBD genetics: common pathways with other diseases. Gut 2011;60:1739-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh NP, Gleeson M, Shephard RJ, Woods JA, Bishop NC, Fleshner M, et al. Position statement. Part one: immune function and exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev 2011;17:6-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarna L, Bialous SA, Jun HJ, Wewers ME, Cooley ME, Feskanich D. Smoking trends in the Nurses’ Health Study (1976-2003). Nurs Res 2008;57:374-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Dam RM, Li T, Spiegelman D, Franco OH, Hu FB. Combined impact of lifestyle factors on mortality: prospective cohort study in US women. BMJ 2008;337:a1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higuchi LM, Khalili H, Chan AT, Richter JM, Bousvaros A, Fuchs CS. A prospective study of cigarette smoking and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease in women. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1399-406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Timing of ascertainment of exposures and outcomes