Abstract

Background

Women with IBS frequently report chronic pelvic pain, however, it is still unanswered whether these are truly separate entities. IBS negatively impacts on quality of life, but the impact of IBS on sexual function is not clear.

Goals

We aimed to 1) describe the impact of IBS on sexual function, and 2) evaluate the association between pelvic pain and IBS, and in particular identify if there are unique characteristics of the overlap group.

Study

The Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire was mailed to an age-and gender-stratified random sample of 1,031 Olmsted County, Minnesota residents aged 30-64 years. Manning (at least 2 of 6 positive) and Rome criteria (Rome I and modified Rome III) were used to identify IBS. Pelvic pain was assessed by a single item. Somatization was assessed by the valid somatic symptom checklist.

Results

Overall 648 (69%) of 935 eligible subjects responded (mean age 52 years, 52% female). Self-reported sexual dysfunction was rare (0.9%; 95% CI 0.3-2.0%). Among women, 20% (95% CI 16-24%) reported pain in the pelvic region; 40% of those with pelvic pain met IBS by Manning, or Rome criteria. IBS and pelvic pain occurred together more commonly than expected by chance (p<0.01). The overall somatization score (and specifically the depression and dizziness item scores) predicted IBS-pelvic pain overlap vs. either IBS alone or pelvic pain alone.

Conclusions

In a subset with pelvic pain, there is likely to be a common underlying psychological process (somatization) that explains the link to IBS.

Keywords: IBS, pelvic pain, sexual dysfunction

Introduction

The irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a very common functional gastrointestinal disorder that is characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort in association with altered bowel habits.1-3 Many IBS patients report a significant impairment of quality of life such as sleep disturbances, reduced work productivity, and decreased energy levels.4-6 Moreover IBS patients frequently complain of extraintestinal symptoms, and manifest excessive comorbidities.7 Notably, women with IBS are more likely than men to report extraintestinal disorders including migraine headaches, bladder discomfort, dyspareunia, and chronic pelvic pain.8, 9 The presence of comorbidities in IBS patients is associated with a reduction in quality of life and increased health care seeking.5, 10, 11

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is one of the most common conditions in women of reproductive age, although the condition has been variously defined in the available studies.12-14 Zondervan et al.14 reported that CPP was the most common diagnosis in primary care units in Great Britain using the definition continuous or episodic (non-cyclic) pain located below the umbilicus, lasting for at least 6 months. CPP is often associated with the irritable bowel syndrome and the similarity between these two conditions in terms of the symptoms, psychosocial factors, and health care utilization has been noted.15-18 Several studies have reported that IBS is associated with common gynecologic problems, including endometriosis, dyspareunia, and dysmenorrhea.9, 19-21 Moreover, Prior et al.22 showed that approximately 50% of women who presented with abdominal pain to the gynecological clinic had symptoms compatible with a diagnosis of IBS. Longstreth et al.19 found symptoms of IBS in nearly half of women having diagnostic laparoscopy for CPP.

Psychosocial factors are associated with CPP and IBS.23 Early life experiences (e.g. abuse), adult stressors (e.g. divorce or bereavement), lack of social support, and other social learning experiences have been reported to be associated with IBS.24-29 Similarly, patients with CPP had increased levels of depression30, high somatization,31, 32 more stressful events,17 and increased physical and sexual abuse.33-35 Notably, women with CPP reported increased disturbances in sexuality and in relationships with their partner.36, 37 IBS patients also reported sexual dysfunction and decreased sexual drive compared to controls.38

The available literature raises the question whether IBS and chronic pelvic pain (CPP) are two separate disease entities or part of the same syndrome with different manifestations. Thus, we aimed to determine the impact of IBS on self reported sexual function, estimate the prevalence of pelvic pain and its overlap with IBS, and evaluate whether there are unique characteristics of the overlap grouping. We hypothesized that the overlap of chronic pelvic pain and IBS occurs more often than expected by chance, because these conditions have a similar pathogenesis.

Materials and Methods

This study reports results from part of a cross-sectional survey of a population-based cohort identified and followed longitudinally since 1988. We have previously used this survey to evaluate the prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders and its associated risk factors.39-42 The survey data for this report were obtained in 1993.

Subjects

The Olmsted County, Minnesota, population comprises approximately 120,000 persons of which 89% are white; sociodemographically, this community resembles the U.S. white population. Mayo Clinic is the major provider of medical care.43 During any given 4-year period, over 95% of local residents will have had at least one local health-care contact.43 Pertinent clinical data are accessible because the Mayo Clinic has maintained, since 1910, extensive indices based on clinical and histologic diagnoses and surgical procedures.44 The system was further developed by the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which created similar indices for the records of the other providers of medical care to Olmsted County residents. The Rochester Epidemiology Project is a medical records linkage system and provides what is essentially an enumeration of the county population from which samples can be drawn.43 Following approval from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, we used this system to draw a random sample of 1031 Caucasian Olmsted County residents aged 30–64 years, stratified by age (in 5-year intervals) and gender (equal numbers of men and women).

The complete medical records of the individuals listed in the sample were reviewed. Subjects were excluded if they had significant illnesses that might cause gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms (n = 14) or impair their ability to complete the questionnaire (e.g. metastatic cancer, major stroke, n = 20), had a major psychotic episode, mental retardation, or dementia (n = 13), or had a history of major abdominal surgery (n = 16). Incarcerated individuals in the Federal Medical Center (n = 31) and subjects for whom contact was prohibited for legal reasons (n = 1) were also excluded. Persons who no longer resided within the county were not eligible to this study. Persons who had developed major illnesses or died during the course of the study were also excluded. Ninety per cent (total of 935 subjects) were eligible to receive the survey.

Survey and questionnaire

For this survey, a modified version of a reliable and valid self-report gastrointestinal symptom questionnaire (Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire, Talley BDQ) and explanatory letters were mailed to this age- and gender-stratified randomly selected sample of Olmsted County residents. The questionnaire was confidential coded with only a study number. This modified version of the BDQ consists of gastrointestinal symptoms that record symptoms of IBS, chronic pelvic pain, and the Somatic Symptom Checklist (SSC). Previous testing has shown this instrument to have adequate content, predictive and construct validity in the outpatient setting, and reliable with a median kappa statistic for the symptom items of 0.78.45

The Somatic Symptom Checklist (SSC) consists of 12 items measuring relevant symptoms and illnesses (namely, headaches, backaches, asthma, insomnia, high blood pressure, fatigue, depression, general stiffness, heart palpitation, eye pain associated with reading, dizziness, and weakness). It does not include any gastrointestinal items. Subjects are instructed to indicate how often each occurred (0=not a problem to 4=occurs daily) and how bothersome each was (0=not a problem to 4=extremely bothersome when occurs) during the past year, using separate 5-point scales.39, 46 A total SSC score is calculated by first averaging the frequency and, separately, the severity of individual items responses, then computing the mean of these two intermediate scores. 39, 46, 47 We have validated this SSC score with SCL 90 R scores in the general population; our somatization score showed a good correlation with the somatization subscale of the SCL-90-R.47

Reminder letters were mailed after 2, 4 and 7 weeks to nonresponders. The remaining non-responders were then contacted by telephone at 10 weeks. Subjects who indicated at any point that they did not wish to participate were not contacted further. A completed questionnaire was returned by 648 subjects out of 935, giving a response rate of 69%.

Definition

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

defined by Manning, Rome I, or modified Rome III criteria.

Manning criteria

IBS was defined as abdominal pain more than six times in the prior year and 2 or more of the following 6 symptoms; 1) abdominal pain that is relieved with a bowel movement, 2) looser stools at the onset of pain, 3) more frequent stools at the onset of pain, 4) sensation of incomplete rectal evacuation, 5) passage of mucus, or 6) abdominal distention.

Rome I criteria

IBS was defined as

At least 3 months continuous or recurrent symptoms of abdominal pain or discomfort which is: 1) Relieved with defecation, and/or 2) Associated with a change in frequency of stool, and/or 3) Associated with a change in consistency of stool; and

Two or more of the following, at least a quarter of occasions or days: 1) Altered stool frequency, 2) Altered stool form (lumpy/hard or loose/watery stool), 3) Altered stool passage (straining, urgency, or feeling of incomplete evacuation), 4) Passage of mucus, 5). Bloating or feeling of abdominal distension

Rome III criteria (modified)

IBS was defined as abdominal pain (more than once a month) in the past three months and at least two of the following characteristics; 1) relief with defecation, 2) onset associated with a change in frequency of stool, 3) onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.

Sexual dysfunction among IBS patients

To estimate the impact of IBS on sexual function, we asked two questions: “Is this pain often brought on or made worse by sexual intercourse?” and “Do your bowel problems affect your sexual activity?”

Chronic pelvic pain

This was measured by one question “Have you had pain in your pelvic region separate from pain in your stomach or belly in the last year?”

Statistical analysis

Age- adjusted prevalence rates and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for CPP were obtained by direct age adjustment to the U.S. white (female) population in 2000. Comparison of observed and expected proportions of subjects with overlapping IBS and CPP was based on the exact binomial test for proportions. The univariate associations between predictors and overlap group of IBS and CPP were evaluated using the chi square test or the Kruskal Wallis test. Potential predictors of the overlap group between IBS and CPP were also assessed using separate logistic regression analyses adjusting for age, body mass index (BMI) and SSC score. These analyses considered the “pure IBS or pure CPP” subgroup as the comparison group (i.e. overlap of IBS and pelvic pain vs. pure pelvic pain, and separately, overlap of IBS and pelvic pain vs. pure IBS).

Results

A total of 648 eligible subjects returned the survey (response rate 69%). The median age of the responding subjects was 52 years, and 52% were female.

Six of 648 subjects (0.9%; 95% CI 0.3-2%), reported abdominal pain made worse with intercourse. Among these six subjects, five met Manning, and two met both Rome I and (modified) Rome III criteria for IBS. A further six (0.9%; 95% CI 0.3-2%) subjects reported that bowel problems effected sexual activity; four subjects out of these six met Manning, one met Rome I criteria, and none met (modified) Rome III criteria for IBS.

Characteristics of CPP & IBS

The observed proportion of women reporting CPP was 20% (67/339) yielding an age-adjusted (US White Females 2000) prevalence of 47.1 per 100,000 population [95% CI: 35.6, 58.5]. The observed proportion of women reporting IBS by Manning criteria was 19% (65/339). Of 65 subjects who met Manning (≥2) criteria, 53 met Manning ≥3 criteria, and 33 met Manning ≥4 criteria.

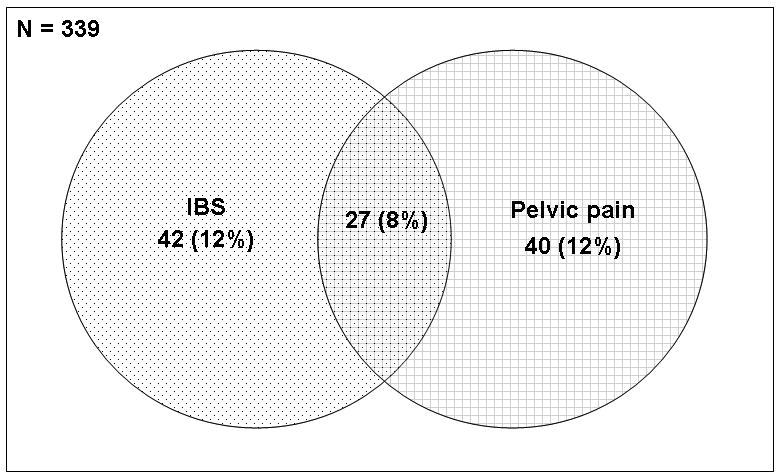

Of 67 subjects with CPP, 39% (26/67) met IBS by Manning (≥2) criteria, 15% met Rome I criteria for IBS (10/67), 7% met modified Rome III criteria (5/67), and 40% (27/67) met one or more sets of IBS criteria. Figure 1 shows the proportion of women in Olmsted County, MN meeting criteria for IBS (by any of the criteria), reporting CPP, and the overlap group. Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics among women with CPP, IBS, overlap (IBS and CPP), or neither.

Figure 1.

Number and proportion of women with IBS alone, pelvic pain alone, and both from Olmsted County Minnesota. Women with IBS were met by Manning or Rome criteria of IBS.

Table 1. Characteristics of the different groups among women with CPP and/or IBS in Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents.

| Neither (n=225) | IBS alone (n= 42) | Overlap of IBS & CPP (n= 27) | CPP alone (n= 40) | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age, mean ± SD (yrs) | 54 ± 10 | 52 ± 11 | 49 ± 11 | 48 ± 8 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| BMI, mean ± SD | 26.5 ± 5.0 | 28.2 ± 6.9 | 26.3 ± 4.1 | 26.2 ± 5.0 | 0.57 |

|

| |||||

| Median SSC score (range) | 0.5(0.0,3.2) | 0.7(0.1,1.7) | 0.8(0.2,3.1) | 0.6 (0.0,1.7) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Current smoker, N (%) | 30 (13%) | 8 (19%) | 5 (19%) | 8 (20%) | 0.47 |

|

| |||||

| Alcohol user, N (%) | 83 (37 %) | 16 (38%) | 12 (44%) | 12 (30%) | 0.68 |

|

| |||||

| Marital Status | |||||

|

| |||||

| Married | 184 (82%) | 32 (76%) | 21 (78%) | 32 (80%) | 0.83 |

|

| |||||

| Education level | 0.07 | ||||

|

| |||||

| ≤ high school | 64 (29%) | 15 (36%) | 6 (22%) | 20 (50%) | |

|

| |||||

| High school/college | 149 (66%) | 24 (57%) | 18 (68%) | 19 (48%) | |

|

| |||||

| ≥College graduate | 11 (5%) | 3 (7%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0) | |

|

| |||||

| Hysterectomy | 58 (26%) | 13 (31%) | 4 (15%) | 4 (10%) | 0.09 |

|

| |||||

| Changing BM menstrual cycle | 13 (6%) | 7 (17%) | 9 (33%) | 15 (38%) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Missing work due to illness, N (%) | 64(28%) | 22(52%) | 11(41%) | 22(55%) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Physician visits more than 5 times, N (%) | 7(3%) | 4(10%) | 4(15%) | 3(8%) | <0.01 |

| For aches or pains in stomach or belly | 4(2%) | 3(7%) | 6(22%) | 1(2%) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| For bowel problems | 2(1%) | 4 (10%) | 3(11%) | 0 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Hospitalization in the last 4 years | 59(26%) | 12(29%) | 7(26%) | 9(22%) | 0.95 |

|

| |||||

| Aspirin, N (%) | 63 (28%) | 25 (60%) | 14 (52%) | 16 (40%) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Acetaminophen, N (%) | 65 (19%) | 21 (50%) | 14 (52%) | 19 (48%) | <0.01 |

|

| |||||

| NSAIDs, N (%) | 62 (28%) | 14 (33%) | 11 (41%) | 16 (40%) | 0.27 |

Based on a univariate test for association of symptom status subgroup with characteristics using the Kruskall-Wallis test for continuous characteristics (age, BMI, SSC score) and the Chi-square test (or Fisher's Exact test) for discrete characteristics.

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; SSC, somatic symptom checklist; BM, bowel movements; NSAIDs non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

No significant univariate association of subject subgroup status with BMI, alcohol use, smoking history, marital status, education, previous hysterectomy, hospitalizations in the last four years and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use were detected. However, subject subgroup status was significantly univariately associated with age, somatic symptom checklist score, and several additional characteristics. In particular, subjects meeting IBS criteria, and subjects with pelvic pain ingested more aspirin and acetaminophen than subjects with no IBS and no CPP, and more frequently reported changes in bowel movements during menstrual periods compared to subjects with no IBS and no CPP. The overlap group with IBS and pelvic pain had the highest somatic symptom checklist median score among the four groups.

Overlap between CPP and IBS

The expected overlap of IBS and CPP was calculated by multiplying the corresponding marginal proportions (i.e. assuming the subgroups were independent), and compared with the observed overlap (using the exact binomial test for proportions). The observed numbers for overlap of IBS and CPP were about 2 times higher than the expected numbers (27 subjects observed vs. 14 expected). The overlap of IBS and CPP was significantly higher than expected by chance alone (p <0.001).

Risk factors for reporting overlap of IBS and CPP versus pure IBS or CPP are shown in Table 2. A high somatic symptom checklist score, depression, dizziness, and weakness were associated with a significantly greater odds for reporting overlap of IBS and pelvic pain compared to the pure IBS group. A high somatic symptom checklist score, headache, depression, and dizziness were associated with a significantly greater odds for reporting overlap of IBS and pelvic pain compared to the pure CPP group. The overlap group of IBS and CPP was not significantly associated with greater physician visits, physician visits for aches or pain, physician visits for bowel problems, or hospitalizations compared to the pure IBS or CPP alone group.

Table 2. Predictors of an overlap of pelvic pain and IBS compared to pure IBS or pure CPP pain alone.

| Overlap vs. pure IBS | Overlap vs. pure CPP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI)‡ | p-value | OR (95% CI)‡ | p-value | |

| Age (per 10years) | 0.96 (0.90, 1.01) | 0.11 | 0.99 (0.93, 1.05) | 0.73 |

| SSC score | 3.5 (1.2, 10.6) | 0.02 | 3.9 (1.2, 12.5) | 0.02 |

| BMI (per unit) | 0.94 (0.85, 1.04) | 0.24 | 0.97 (0.86, 1.09) | 0.62 |

| Current Smoking (relative to No) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.9) | 0.26 | 0.5 (0.1, 2.2) | 0.34 |

| Alcohol (>6 drinks/wk) | 2.4 (0.4, 14.0) | 0.32 | 2.1 (0.3, 12.9) | 0.43 |

| Married | 1.1 (0.3, 4.6) | 0.92 | 1.0 (0.2, 4.3) | >.99 |

| Education level | ||||

| College, professional training | 0.5 (0.2, 1.9) | 0.33 | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) | 0.03 |

| Hysterectomy | 0.2 (0.04, 1.2) | 0.09 | 0.9 (0.1, 7.1) | 0.94 |

| Changing BM by menstrual cycle | 1.9 (0.5, 7.0) | 0.32 | 0.8 (0.3, 2.5) | 0.71 |

| Missing work due to illness | 0.6(0.2, 1.8) | 0.35 | 0.6(0.2, 1.7) | 0.31 |

| Physician visits more than 5 times | 0.7(0.1, 4.1) | 0.69 | 2.1(0.3, 15.9) | 0.46 |

| For aches or pains in stomach or belly | 4.1(0.7, 24.1) | 0.11 | insuff | -- |

| For bowel problems | 0.5(0.1, 1.2) | 0.47 | insuff | -- |

| Hospitalization in the last 4 years | 0.8(0.2, 2.9) | 0.79 | 1.1(0.3, 4.0) | 0.86 |

| Aspirin | 0.8 (0.3, 2.5) | 0.76 | 1.7 (0.6, 5.1) | 0.35 |

| Acetaminophen | 1.2 (0.4, 3.7) | 0.77 | 1.0 (0.4, 3.1) | 0.95 |

| NSAIDs | 1.2 (0.4, 3.7) | 0.74 | 1.1 (0.4, 3.3) | 0.85 |

| Headache* | 1.4 (0.8, 2.4) | 0.21 | 1.7 (1.0, 2.8) | 0.048 |

| Depression* | 2.8 (1.5, 5.1) | <0.001 | 1.8 (1.1, 2.9) | 0.018 |

| Dizziness* | 1.9 (1.1, 3.2) | 0.03 | 2.6 (1.2, 5.4) | 0.012 |

| Weakness* | 1.7 (1.0, 3.0) | 0.048 | 1.6 (0.9, 2.8) | 0.091 |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; SSC, somatic symptom checklist; BM, bowel movements; NSAIDs, non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; BM=bowel movement; insuff=insufficient frequencies

Odds ratios [95%CI] adjusted for age, BMI and SSC score

except for individual SSC items which were adjusted for just age and BMI

Discussion

This study has shown that the prevalence of CPP was 20% among women in Olmsted County, Minnesota; of 129 women with CPP, 39% met diagnostic criteria for IBS by Manning, 15% by Rome I criteria, and 7% by modified Rome III criteria. Importantly, IBS and CPP occurred together more commonly than expected by chance. Notably, in the general population we found that high somatization scores, depression and dizziness were all individually associated with IBS-pelvic pain overlap vs. both IBS alone and pelvic pain alone. On the other hand, just 1% of the population reported abdominal pain made worse with intercourse and only another 1% reported bowel problems affecting sexual activity.

Irritable bowel syndrome has been reported to negatively impact on quality of life, decreasing energy levels, changing appetite, and inducing sexual dysfunction. 4-6 Guthrie et al.48 studied sexual dysfunction in 50 patients with IBS compared with 30 patients with active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and 30 patients with active duodenal ulcers; they showed that irritable bowel syndrome was associated with a profound impairment of sexual function, with 83% reporting problems compared with 30% of women with IBD and 16% of those with duodenal ulcers. In another study from a referral setting, Fass et al. showed that up to 50% of patients with IBS reported self-reported sexual dysfunction compared to 16% of healthy controls. Although our study showed only a small portion of the population experienced sexual dysfunction, the majority of subjects who complained about sexual dysfunction met diagnostic criteria for IBS.

Patients with the irritable bowel syndrome often are seen in gynecological clinics. Williams et al.15 studied the prevalence and characteristics of IBS among 987 women with chronic pelvic pain in a referral setting. In this study, they showed that 35 percent of women with pelvic pain met Rome I criteria for IBS, which is similar to our community study where 22% of women with CPP met Rome criteria; other groups have observed similar rates.21, 22 Williams et al.15 reported that certain characteristics, including age 40 years or older, muscular back pain, the Symptom Checklist-90 global index score in the top quartile, depression, six or more pain sites, and a history of adult physical abuse, distinguished women with IBS from women with chronic pelvic pain, and suggested that IBS and chronic pelvic pain are not simply manifestations of the same disorder. However, in this study the overlap group of CPP and IBS was only compared with those having chronic pelvic pain alone, a significant limitation. Furthermore, in a recent systemic review, Matheis et al.17 showed many similarities between IBS and CPP in terms of stressful life events, physical and sexual abuse rates, abnormal illness behavior and medical co-morbidity. We observed that the overlap of IBS and CPP occurred more commonly than expected by chance, suggesting a similar underlying pathophysiology in a subset of population. In a systemic review, Whitehead et al.7 reported that chronic pelvic pain was one of best documented associations with IBS among all non-gastrointestinal and non-psychiatric disorders (a median of 50% with pelvic pain had IBS). Another study of the comorbidity of IBS in primary health care 49 reported that 48 of 51 symptom-based diagnoses were significantly more common in IBS patients versus controls including pelvic pain, although the findings of this study were based on an administrative database rather than on a direct method of measuring somatic symptoms. A recent systemic review50 showed that IBS patients have a twofold increase in somatic comorbidities compared to controls including chronic pelvic pain. Our study showed that the overlap group of IBS and CPP reported higher a somatization score compared to pure IBS or the pure CPP group. Notably, depression, headache, dizziness, and weakness were significantly associated with reporting the overlap of IBS and CPP compared to pure IBS or CPP. It is therefore conceivable that at least a subset of IBS share a common pathophysiology with CPP, and somatization may be a key explanation.

The strengths of the current study include the investigation of a random community sample who were not seeking health care for their gastrointestinal complaints or gynecological complaints, which should have minimized selection bias. The fact that we employed a previously validated self-report symptom questionnaire also increases confidence in the results. This study also had limitations. These data may not be generalized to the whole population because the racial composition of this community is predominantly White Caucasian. The prevalence of IBS and CPP may vary across different countries and cultures, but at a minimum our data are probably generalizable to the US Caucasian population. Notably, the IBS population selected in this study met the Manning or Rome criteria; as the Rome criteria are specific but not sensitive, we do not believe this is a serious limitation.51 Another potential limitation is the definition of chronic pelvic pain we used was based on a single question; this may have been subject to recall bias, or alternatively may have overestimated the problem. However, we did specifically ask subjects to separate pelvic pain from pain in the abdomen, and this should have minimized any confusion. Finally, we only included a limited number of items that inquired about sexual dysfunction (two) which may have underestimated the problem. While the questionnaire was confidentially coded (aside from a study number), the questions asked about sensitive matters and may have been under-reported.

We conclude from this population-based study that at least a subset with IBS and chronic pelvic pain share a common pathophysiology, rather than being distinct clinical entities in the general population; notably, somatization appears to be the link. Further studies are required to clarify the relationship between IBS and CPP, and determine whether evaluation and treatment strategies should be distinct.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Lori R. Anderson for her assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Grant Support: This study was made possible in part by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Grant #R01-AR30582 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases)

Abbreviations

- BDQ

bowel disease questionnaire

- BM

bowel movement

- BMI

body mass index

- CPP

chronic pelvic pain

- GI

gastrointestinal

- IBS

irritable bowel syndrome

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug

- SCC

somatic symptom checklist

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Talley and Mayo Clinic have licensed the Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Longstreth GF. Definition and classification of irritable bowel syndrome: current consensus and controversies. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:173–87. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson WG. Irritable bowel syndrome: pathogenesis and management. Lancet. 1993;341:1569–72. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90705-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zighelboim J, Talley NJ. What are functional bowel disorders? Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1196–201. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90293-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vege SS, Locke GR, 3rd, Weaver AL, Farmer SA, Melton LJ, 3rd, Talley NJ. Functional gastrointestinal disorders among people with sleep disturbances: a population-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1501–6. doi: 10.4065/79.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:654–60. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.16484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean BB, Aguilar D, Barghout V, Kahler KH, Frech F, Groves D, Ofman JJ. Impairment in work productivity and health-related quality of life in patients with IBS. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:S17–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1140–56. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee OY, Mayer EA, Schmulson M, Chang L, Naliboff B. Gender-related differences in IBS symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2184–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowell MD, Dubin NH, Robinson JC, Cheskin LJ, Schuster MM, Heller BR, Whitehead WE. Functional bowel disorders in women with dysmenorrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1973–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Locke GR, 3rd, Weaver AL, Melton LJ, 3rd, Talley NJ. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: a population based nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:350–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–31. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalpiaz O, Kerschbaumer A, Mitterberger M, Pinggera G, Bartsch G, Strasser H. Chronic pelvic pain in women: still a challenge. BJU Int. 2008;102:1061–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Latthe P, Mignini L, Gray R, Hills R, Khan K. Factors predisposing women to chronic pelvic pain: systematic review. Bmj. 2006;332:749–55. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38748.697465.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Prevalence and incidence of chronic pelvic pain in primary care: evidence from a national general practice database. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;106:1149–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams RE, Hartmann KE, Sandler RS, Miller WC, Steege JF. Prevalence and characteristics of irritable bowel syndrome among women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:452–8. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000135275.63494.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longstreth GF. Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1994;49:505–7. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199407000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matheis A, Martens U, Kruse J, Enck P. Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic pelvic pain: a singular or two different clinical syndrome? World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3446–55. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i25.3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams RE, Hartmann KE, Sandler RS, Miller WC, Savitz LA, Steege JF. Recognition and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome among women with chronic pelvic pain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:761–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longstreth GF, Preskill DB, Youkeles L. Irritable bowel syndrome in women having diagnostic laparoscopy or hysterectomy. Relation to gynecologic features and outcome. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:1285–90. doi: 10.1007/BF01536421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prior A, Wilson K, Whorwell PJ, Faragher EB. Irritable bowel syndrome in the gynecological clinic. Survey of 798 new referrals. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1820–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01536698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Jenkinson CP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. Chronic pelvic pain in the community--symptoms, investigations, and diagnoses. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:1149–55. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.112904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prior A, Whorwell PJ. Gynaecological consultation in patients with the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1989;30:996–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.7.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walker EA, Gelfand AN, Gelfand MD, Green C, Katon WJ. Chronic pelvic pain and gynecological symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;17:39–46. doi: 10.3109/01674829609025662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR. Self-reported abuse and gastrointestinal disease in outpatients: association with irritable bowel-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:366–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delvaux M, Denis P, Allemand H. Sexual abuse is more frequently reported by IBS patients than by patients with organic digestive diseases or controls. Results of a multicentre inquiry. French Club of Digestive Motility. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:345–52. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ali A, Toner BB, Stuckless N, Gallop R, Diamant NE, Gould MI, Vidins EI. Emotional abuse, self-blame, and self-silencing in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:76–82. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200001000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Robinson JC, Heller BR, Schuster MM. Effects of stressful life events on bowel symptoms: subjects with irritable bowel syndrome compared with subjects without bowel dysfunction. Gut. 1992;33:825–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.6.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett EJ, Tennant CC, Piesse C, Badcock CA, Kellow JE. Level of chronic life stress predicts clinical outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1998;43:256–61. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy RL, Olden KW, Naliboff BD, Bradley LA, Francisconi C, Drossman DA, Creed F. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1447–58. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorencatto C, Petta CA, Navarro MJ, Bahamondes L, Matos A. Depression in women with endometriosis with and without chronic pelvic pain. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85:88–92. doi: 10.1080/00016340500456118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richter HE, Holley RL, Chandraiah S, Varner RE. Laparoscopic and psychologic evaluation of women with chronic pelvic pain. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1998;28:243–53. doi: 10.2190/A2K2-G7J5-MNBQ-BNDE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peveler R, Edwards J, Daddow J, Thomas E. Psychosocial factors and chronic pelvic pain: a comparison of women with endometriosis and with unexplained pain. J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:305–15. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00521-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rapkin AJ, Kames LD, Darke LL, Stampler FM, Naliboff BD. History of physical and sexual abuse in women with chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:92–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walling MK, O'Hara MW, Reiter RC, Milburn AK, Lilly G, Vincent SD. Abuse history and chronic pain in women: II. A multivariate analysis of abuse and psychological morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:200–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walling MK, Reiter RC, O'Hara MW, Milburn AK, Lilly G, Vincent SD. Abuse history and chronic pain in women: I. Prevalences of sexual abuse and physical abuse. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:193–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fry RP, Crisp AH, Beard RW. Patients' illness models in chronic pelvic pain. Psychother Psychosom. 1991;55:158–63. doi: 10.1159/000288424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zondervan KT, Yudkin PL, Vessey MP, Dawes MG, Barlow DH, Kennedy SH. The prevalence of chronic pelvic pain in women in the United Kingdom: a systematic review. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:93–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fass R, Fullerton S, Naliboff B, Hirsh T, Mayer EA. Sexual dysfunction in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and non-ulcer dyspepsia. Digestion. 1998;59:79–85. doi: 10.1159/000007471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Locke GR, 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Melton LJ. Risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: role of analgesics and food sensitivities. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:157–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang JY, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Risk factors for chronic constipation and a possible role of analgesics. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2007;19:905–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2007.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Functional constipation and outlet delay: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:781–90. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90896-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Onset and disappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:165–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kurland LT, Molgaard CA. The patient record in epidemiology. Sci Am. 1981;245:54–63. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1081-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Melton J, 3rd, Wiltgen C, Zinsmeister AR. A patient questionnaire to identify bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:671–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-8-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Attanasio V, Andrasik F, Blanchard EB, Arena JG. Psychometric properties of the SUNYA revision of the Psychosomatic Symptom Checklist. J Behav Med. 1984;7:247–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00845390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choung RS, Locke GR, 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, Talley NJ. Psychosocial distress and somatic symptoms in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: a psychological component is the rule. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1772–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guthrie E, Creed FH, Whorwell PJ. Severe sexual dysfunction in women with the irritable bowel syndrome: comparison with inflammatory bowel disease and duodenal ulceration. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;295:577–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6598.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Levy RR, Feld AD, Turner M, Von Korff M. Comorbidity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2767–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riedl A, Schmidtmann M, Stengel A, Goebel M, Wisser AS, Klapp BF, Monnikes H. Somatic comorbidities of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:573–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ford AC, Talley NJ, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Vakil NB, Simel DL, Moayyedi P. Will the history and physical examination help establish that irritable bowel syndrome is causing this patient's lower gastrointestinal tract symptoms? Jama. 2008;300:1793–805. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]