Introduction

Globally more than 37 million people have been infected with the HIV virus.[1] Sub-Saharan Africa remains the region most heavily affected by HIV, accounting for 67% of all young people living with HIV and for 75% of AIDS deaths in 2007.[2] In Uganda, adolescents are at increased risk of HIV infection compared to any other age group.[3] Evidence from the AIDS Information Centre shows that among 15–24-year-olds who were testing for the first time, HIV prevalence was 3% among young men and 10% among young women in 2002. Since 2000, Uganda’s HIV prevalence rates have been characterized by stabilization at a level ranging from 6–7%[2] There are indications from the national surveillance system corroborated by data from longitudinal cohort studies however, of an apparent increase in HIV prevalence and incidence during the last few years.[2] Thus, not only are young people are still vulnerable to HIV infection in Uganda, but that risk may be increasing.

There has been growing interest in the use of technologies such as computers, the Internet and mobile phones to enhance health promotion and disease prevention.[4–9] HIV prevention programs have led the technology health field.[5] Technology has several advantages as a health delivery tool: it can provide a private and confidential environment, which is particularly important in places where stigma could limit service access.[10] They also are a cost-effective: dissemination of online material is the same if one person or 100,000 people use the program.[4] In the developed world, computer-based HIV prevention programs demonstrate efficacy in changing HIV-related risk behaviors [5]. There also is evidence that the Internet and computers may be a feasible and attractive approach for developing country and other resource-limited settings; [4,11–13] Parallel data in the African context are lacking.

As part of the effort to increase technology-based HIV prevention research in resource-limited settings, CyberSenga is a research project that aims to develop and test an Internet program for adolescents in Uganda. Our overall goal with the study described here was to conduct qualitative focus groups to inform the development of the content and structure for the CyberSenga program. Specific objectives included: 1) documenting experiences youth had with sexuality education and their educational needs related to HIV and sexuality; 2) documenting reactions to and acceptability of the concept of an Internet based HIV prevention program; and 3) identifying preferences for content and structure of such a program.

Methods

Design

We used a qualitative approach, conducting three focus groups with secondary school students.

Setting

Focus groups were conducted in the CyberSenga project office in Mbarara, Uganda. Mbarara is a small urban community of 97,500 individuals in southwestern Uganda, a five hour drive from the capital city, Kampala. The prevalence of HIV in South West Uganda, where Mbarara is situated, is 5.9 percent.[2]

Participants and sample

The CyberSenga program established a working relationship with five secondary schools at the outset of the project with the intent to select program participants for all program activities from one of these schools. Focus group participants were enrolled in one of these five schools, levels Secondary-1 (S1) through Secondary-3 (S3). Three groups with five participants each were conducted. A total of five female and ten males participated. Participants were peer-nominated popular opinion leaders in their respective school class. Readers interested in the nomination process may contact the Authors for further information.

Instruments

Focus groups are small group discussions about a pre-specified topic or topics. While the topics are identified prior to the discussion, the questions are open-ended to allow for expected as well as unexpected themes to emerge in the group discussion. Based upon study objectives, our discussion topics were: (a) prior experiences youth had with sexuality education; (b) educational needs related to HIV and sexuality; (c) reactions to and acceptability of the concept of an Internet based HIV prevention program; and (d) preferences for content and structure of such a program. Each group was moderated by CyberSenga staff who were Ugandan and fluent in the local languages. Each group also had an observer who took notes and documented non-verbal body language and information about the environment (e.g. it was noisy in the room). Groups lasted between 75 and 90 minutes and were conducted mostly in English. If participants felt more comfortable expressing their thoughts in the local language however, they were encouraged to do so.

Each group was tape recorded and two were transcribed. The third group was convened during a very loud thunderstorm and none of the voices could be heard on the tape. We therefore relied primarily on detailed observer notes to analyze data from this group.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using a content analysis. The first step included open coding where categories were assigned to all pertinent segments of text. The categories were allowed to emerge from the text and were not predetermined. Each transcript and all observer notes were coded. The second step was axial coding: codes were group together to identify patterns in the coding and to discern the frequency with which codes were assigned. The frequency of codes allowed for assessment of when saturation was achieved versus when outlier ideas were expressed. The last step was to synthesize the patterns and identify key findings.

Ethics

All procedures were reviewed and approved by both the local (Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST) IRB) and US-based (Chesapeake IRB) IRBs. Three levels of written informed consent or assent were required for study participation: first, headmasters from each school gave their consent to recruit student participants; second, parents gave informed consent for their children to take part in the study; third, every participant completed an informed assent.

RESULTS

1. Experiences with sexuality education

Participants reported exposure to sexuality education at home, from family members, and from teachers at school. One participant indicated they had learned about sex from a peer. Most mentioned that sexuality education at home was delivered by mothers, although some indicated that an older sister or brother, or aunt or uncle had talked to them about sex and sexuality.

Sexuality education topics included information on HIV specifically. The emphasis on HIV appeared to eclipse other topics, specifically pregnancy and parenting, and STD prevention. Table 1 includes selected quotes from participants related to their sexuality education, indicative of the emphasis on HIV.

Table 1.

Selected quotes from participants related to their sexuality education

| Topic | Quote |

|---|---|

| Sexuality Education at home | First of all it begun from home. By the time we were growing my mum used to tell us about HIV and sex |

| I first learnt about sex from my sister. She told me about sex and the disadvantages and she told me that it is normal. She told me that you can avoid it by avoid having boyfriends and by reading novels and news papers in my free time | |

| Sexuality Education at school | Even our teachers at school they used to tell us about HIV. Then we come to secondary at the end of the term, they tell us the disadvantages, and they tell us what the right thing to do is. |

| They used to tell us that if you get HIV, you will die and if you get pregnant your education will stop from there. | |

| At home I have not learnt from anyone but at school, we are always given talks about sex, about these early pregnancies and then; may be from home what keeps me moving is that I know that my parents love me. So I do not want to disappoint me. |

Some youth noted receiving messages associating sexuality with death or disaster: They used to tell us that if you get HIV, you will die and if you get pregnant your education will stop from there. As another example: AIDS kills and [people] should abstain from sex and use condoms. This may not be a university message however as one young woman indicated her sister told her sex was “normal”.

Participants rarely mentioned that sexuality education included information on forming and sustaining healthy sexual relationships. One exception is the following from a young woman about anticipating and managing sexual feelings: they tell us about the way we should handle ourselves, and they tell us about growing because that sexual feeling can come when you are around.

2. Educational needs related to HIV and sexuality

Two sub categories within this topic were identified. First, participants shared their perspective on the content that should be covered in the CyberSenga program. They also made misstatements about HIV that suggested myths and misinformation that must be addressed in the program. Second, they also offered opinions and suggestions for how to deliver this content.

a. Content

HIV information

Participants indicated that we should have some basic information about HIV and how it is transmitted. One participant indicated needing to know more about the HIV/AIDS Scourge, and others mentioned the importance of raising awareness of HIV being fatal. For example:

Me, I am going to design that one of AIDS, the person the dangers of AIDS and you tell the person about the people who have been dying of AIDS and very important people whom we should be having in our country. Tell the person the rate at which people are dying of that scourge. So I think that when you put all that about HIV I think that person will try to avoid it.

Abstinence

Abstinence was a popular theme across all three groups: Me, I can tell them to abstain if they had had sex before then they can abstain. Another said: Abstinence is good. If you abstain from sex there is no chance of getting those sexual diseases, pregnancy. Abstinence is good.

Participants struggled with their perceived contradiction between emphasizing abstinence and discussing condoms with adolescents: You are telling people to abstain, now you bring in condoms, if they are abstaining then why bring in the condoms? This seemed to be compounded by the perception that condoms were not effective:

don’t you if you put on something about condoms, you are encouraging people to get involved in sexual immorality?...we know condoms are not 100% perfect and then you bring them in; me I think it would be, kind of- kind of contradicting?

People who have failed completely to abstain, they go for condoms but since they have said that they are not perfect, you never know …Sometimes when they are manufactured, I think they are able to leave those holes which lead to the mixing of the fluids.

There was support for an emphasis on abstinence while considering a continuum of protective behaviors; Ultimately maybe I can put what it means the advantages [of abstinence], the disadvantages like that, said one participant, and: sometimes it would be right to tell them to use condoms because they are already sexually active, said another.

Misinformation

Participants made some statements that were incorrect or misinformed, specifically about condom use. The first misperception that was raised was the notion that most condoms have holes or are poorly manufactured, which is why they should not be relied upon: me I think that abstinence is better than using condoms. Because condoms are not 100% because you can get it when it is expired or when it is torn so I prefer abstinence, said a participant.

The second misperception, expressed by women, spoke to male-to-female dynamics and control in relationships: where you were showing us the boy and the girl, you should also show us that the boy should decide because it seems that it is left for us the girls only to decide.

A third misperception, particularly held among the young men, was the idea that women want to trap them and “spoil their future.”

Like if you have a girl friend and that girlfriend does not like you and then she wants to spoil your future, she can pierce the condom and you will end up getting HIV.

Condoms

Despite the results presented above that show support for an emphasis on abstinence, participants did agree that it would be appropriate to include content on condoms. I think condoms can work for people who are already [having sex], said a participant. They mentioned the need for education around condom acquisition (I think they should include where to find [condoms]) and use: [they need to know] how to use them because there are some people who don’t know how to use them. Certainly however, the majority of the discussion about program content focused on abstinence.

Self Esteem

Participants mentioned several times the need for an emphasis on building self esteem as part of the program content:

I would put a part to first guide them to help them love themselves for who they are. You know most times we don’t accept ourselves for who we are and we tend to be like others. So if you love yourself you can accept yourself and you do something which can give you bright future

A related issue is the emphasis on achievement of life goals as an approach to sharing content about HIV prevention. One young man said:

You see this girl is having something to achieve. She likes her education, she is protecting herself from HIV and AIDS; me I think that it is not right she should be telling the boy she should be telling the truth and the boy also gets aware. So I think that this girl should be able to do something to tell the boy.

Values

While not mentioned with frequency, there were two participants who indicated having the perception that sexual behavior represented “immorality.” This is related to the discussion presented above representing the confusion about how you could simultaneously promote abstinence and condom use. Another participant indicated that sexuality education should be “spiritual,” suggesting the importance of considering values as content for the program.

Coercive sex

While not frequently mentioned, the participants did indicate having a perception that coercive sex occurred – primarily through contact with adults. One participant mentioned “sugar daddies,” saying that the Senga has now become a broker for sugar daddies: the Sengas don’t care. She can just pick you from school and she takes you to a sugar daddy - some thing like that. Another mentioned the expectation that supporting young girls in school should translate into sexual favors: [adults think] you pay fees for my daughter and after I will gave her to you. A third participant repeated a perception that it was common for older men to date younger girls when reacting to a particular element of the program we pilot tested:

the boy is young; he looks like an adolescent. Now that these days they are old men that go out with young girls I think the boy should be older than the girl.

b. Structure

In addition to specific ideas for what types of content our CyberSenga program should include, the participants talked to us about approaches for delivery of content and ways to structure the program that they liked.

Literacy

Participants liked program elements that included flash technology and simple language. They suggested that making things easy to read would make them easier to understand.

Problem Solving and Skills building

Table 2 offers a number of other statements that support the appreciation for a problem solving and skills building approach. Participants seemed to appreciate having an opportunity to “practice” different activities on a program using a game format, and they also appeared to appreciate having a very specific and concrete issue to address and respond to. Consider this exchange: Focus group leader: Why do you think it is important to first show the problems and then the solution? Participant: that person may be wondering may be if you see that real cause which you have shown, the person may be able to realize the problem and then get the solution

Table 2.

Statements related to preferences for content delivery using problem solving and skills building

| Topic | Quotation |

|---|---|

| Problem solving |

I would like to know how I can determine my problems forces me to think about the problem. may be if I have the problem I would continue to the next page and then I would try to see the goals I have to achieve and then I would try to find out that information |

| When I see these five steps, it means there is something, may be I think there is something hidden may be other steps so I have to continue. | |

| I think that I have a problem and it is really disturbing because I see the steps… I think if I read this information, I really see that it is really disturbing if I see the steps if I have the problem I think I can go on. |

Role models and Testimonials

Participants liked the concept of using real people to tell stories and deliver information about HIV. In some instances however, they advocated for approaches that may stigmatize or marginalize persons with HIV. Consider the following statements:

I would find out from people true life stories. I would try to find out from the people especially the youth what makes them to get involved in sexual behavior. When you get such stories you get interested.

I would put there like someone suffering from HIV the way that person looks like, so when that person is watching that program, they will try to fear and avoid sexual immorality. Then may be God fearing like Ten Commandments because most of the problems are caused by not fearing God.

3. Acceptability of the concept of a CyberSenga program

We asked participants to react to the program name, CyberSenga, and tell us what it meant to them. There was universal understanding of the term Senga, and multiple expressions of appreciation for the attention to the cultural value in Uganda of communicating with your father’s sister about issues related to sex, sexual development and sexual decision making. The following quote illustrates this finding: Senga itself is a lady born with your father… who always give us advise all the time…something to do with advising especially.

There was no familiarity with the term Cyber. When the facilitators described that Cyber in this context meant that the program would be based on the Internet, there was immediate acceptance and understanding of the meaning.

Overall the participants agreed that a substantial benefit of such an approach was privacy and confidentiality. They liked being able to get information and explore these topics in private, and they contrasted this benefit with the alternative of seeking advice and information from an actual Senga. Table 3 includes quotes to support this finding.

Table 3.

Positive reactions to the CyberSenga program concept

| Privacy | me I think this program is better. It is more private; when you ask about some sensitive things, you feel shy and when these people come to school, when you have personal problems, you can not ask because you are many, you just feel shy. but when you go to this program you get to know your problem and you discuss it and you find the solution without being interrupted by any one. |

| Okay, to me personally I can not think that I can sit with my auntie and we talk about those things I think I will be shy to talk with her but here I think I can look at the program and get out the solution for my self | |

| Confidentiality | Me I have been learning about HIV and I have been talking with my friends but most of the time you can be with other people and it can cause gossiping but something like this can not cause gossiping because you take your computer somewhere on the internet and you learn about this |

| CyberSenga would be better because you find you are not used to your parents and you feel uneasy asking certain things and you feel like how will I start telling mum about it and for you as a person you feel asking because there are brothers around you or even at school your fellow students may laugh at you and you may feel uncomfortable |

4: Preferences for CyberSenga program content

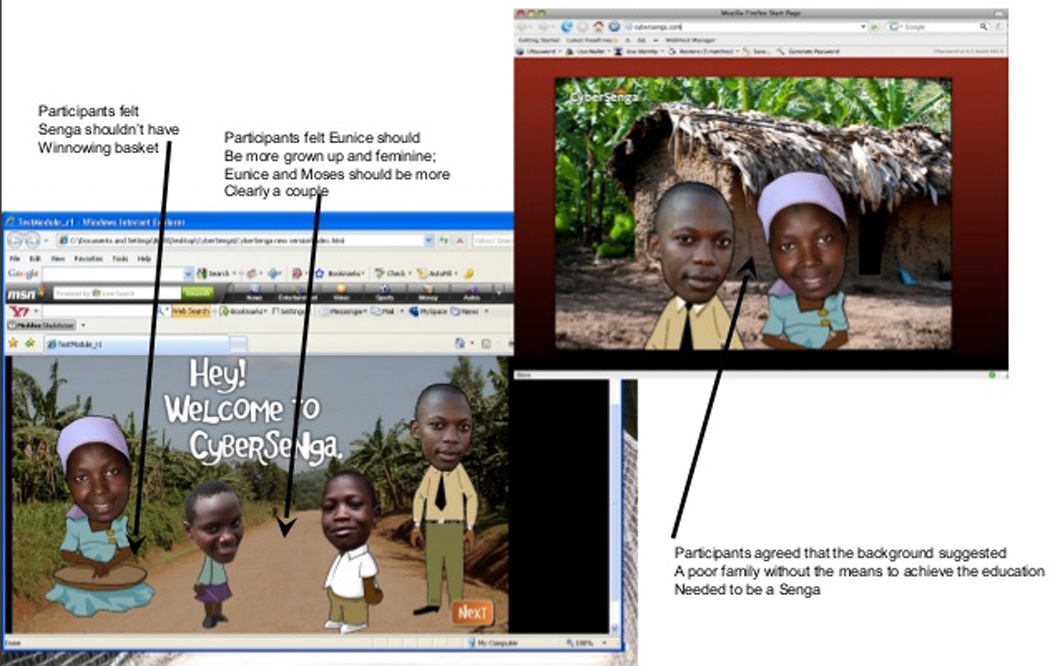

Participants were offered initial ideas for delivering program content and asked for their reactions. The initial concepts included several cartoons that were intended to depict a CyberSenga and Cyber Kojja (the male equivalent to the Senga), superimposed on a rural background scene from the local area near Mbarara. They also included part of a problem solving vignette, including cartoons of the CyberSenga and Kojja as well as two young people, named Eunice and Moses. The initial design is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Credibility for the Cyber Senga and Cyber Kojja

The participants appreciated the inclusion of the Senga and Kojja and felt that using these characters was a key feature that made the program credible. It is part of the Luganda culture, an important part, said a participant. However, support for the use of a CyberSenga and Kojja was not universal. There was a discussion in one group about the appropriateness of the concept. Here is an excerpt:

We should consult elders instead of listening to the program: If you consult the elders, they will be able to tell you when you are seeing them because if someone comes to tell you in the program sometimes you can not believe them. But if the person tells you face to face then you can believe them.

Another participant responded:

I think we will be able to achieve this. I think most people know about those things and they can not open to our own Sengas. We have come to fear our Sengas instead of respecting them.

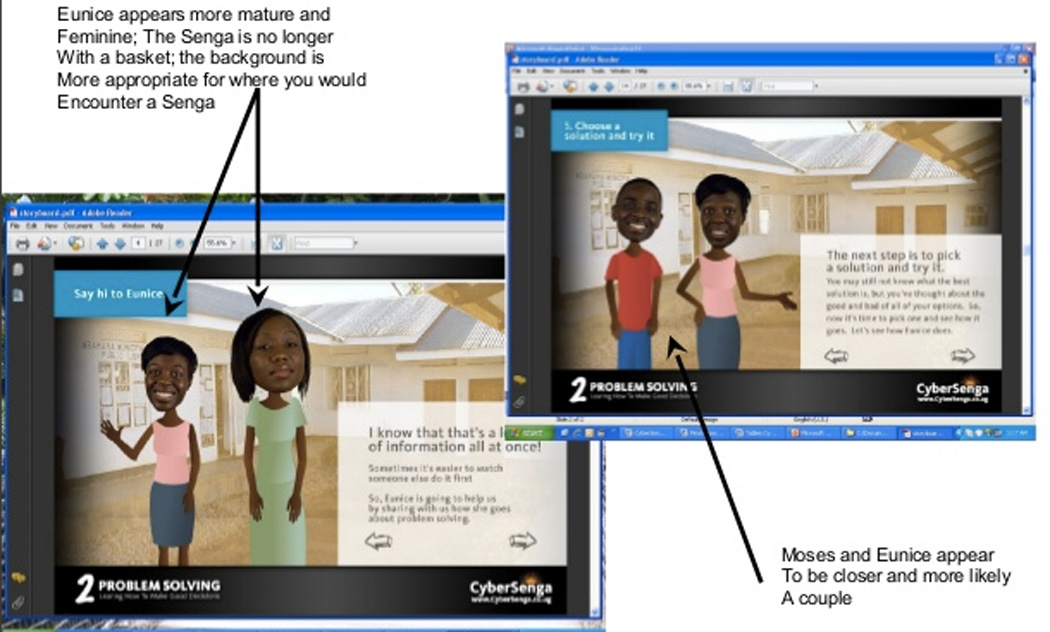

Characteristics of Senga and Kojja and the environment

The participants expected that the Senga and Kojja should be elders, but not too old; that they should be shown wearing traditional dress; and that they should be serious but not intimidating. For most participants, it was important that the Senga be friendly and approachable, not wearing make up, and not involved in other activities such as winnowing or sorting grain so they can pay appropriate attention to the serious conversation at hand.

The participants were in agreement that the initial representation of the Senga and Kojja in front of an earthen kitchen in a rural setting was not appropriate. They generally perceived that this environment was of a very poor family, and drew the conclusion that this family would not have the education or means to become a Senga or Kojja and were therefore not credible. They reacted to another element of the program depicting the Senga, Kojja, and two young people standing on a road as not only inappropriate, but dangerous. Table 4 offers statements that illustrate these preferences.

Table 4.

Preferences for presentation of the CyberSenga and CyberKojja

| Topic | Quote |

|---|---|

| Elder | Normally, the aunties who are the Sengas they are always old so it would be better if they were old. |

| Okay there are people you look at and you look at and you’re like, yeah they have a point and you listen but this one I don’t think so. May be if they were older | |

| the Senga should not be too old because those too old people are hard to approach so you can make her in a way that she looks approachable. | |

| Demeanor | I think people who are talking about serious things should not be over smiling like that |

| me I think she is sorting although I don’t see what she is sorting. she is like holding a cushion. When you are talking to people you can not do two things at a go; holding something and then talking to people so I think that she should concentrate on one thing | |

| Location | Because he is seated on the road now what if the car comes |

| About the background, they are some people who come from the town so if I am moving around and I see something from that house there, I don’t think it is very good… I think a house should be modern | |

|

It should be like a house there is bench people are seated there which can show something. …and the Senga should be seated on the chair and then the boy or the girl is also seated there and they should be having a table. …the Senga or the child should be seated on mat | |

| Dress and appearance | I think a Senga should be putting on a Gomesi (traditional wear for women) and a man should be putting on a kunzu |

| Sengas are normally natural they don’t put on make up; The Senga should not make up because when you make up, you really look someone going for an outing. |

Portrayal of Eunice and Moses

As shown in Figure 1, beta characters in the website program had photos of real people superimposed onto cartoon bodies. Participants also saw initial designs including cartoons; however the added ‘reality’ of the photos superimposed on cartoon bodies was the most popular, and the participants identified better with these characters. They did not like the specific portrayal of Eunice, however, the young girl. I think that the program is nice but then when it comes to Eunice she does not look like a girl, said one participant, and the hair is not combed and the way she is putting on said another. Participants in another group concurred, saying: the boy looks okay but the girl does not look okay. The dressing and then the way she looks like; she is dressed like in a uniform and she looks like she is out somewhere.

The participants cautioned that we needed to make it clear that Eunice and Moses were boyfriend and girlfriend. They suggested the couple be older, that they be positioned more closely to one another, and that they be looking at each other:

The boy and a girl should look older. When they are old that is when they think about the boyfriend and the girl friend. They should be some people who have grown up like the people who are old enough to make the right choice.

Discussion

Three focus groups were conducted to illicit information about common exposure to sexuality education as well as reactions to CyberSenga Internet HIV prevention program in development. Participants were popular opinion leaders in their respective school class, and thus we anticipate their opinions are respected among other youth in Mbarara secondary schools.

Participants indicated that they were exposed to sexuality education at home, from family members, and from teachers at school. Youth accounts indicated the content of sexuality education was focused primarily on HIV and may not have included as much information about pregnancy prevention, prevention of other sexually transmitted diseases, nor how to cultivate healthy sexual relationships. These data are consistent with other research in Africa on access to sexuality education among youth.[14,15]

Abstinence was a commonly discussed theme across all three groups and many participants appeared to support an emphasis on abstinence as an important part of the program content. Given the strong focus on abstinence noted in previous qualitative research conducted with this age group in Uganda [14], it seems likely that this support was at least in part due to social desirability.

Participants offered important suggestions to be included in the program content about self esteem. They strongly identified with the elements of the program that included problem solving and sharing of stories.

Participants strongly supported the concept of “CyberSenga”. There was universal understanding of the Senga and appreciation for the attention to the cultural value the Senga represents in Uganda. The term “Cyber” was quickly understood an accepted upon explanation. Participants suggested they liked the idea of accessing sexuality information through the Internet primarily because it was private and confidential. We incorporated participants’ specific suggestions for improvements to the program design, shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

This study had some limitations. The selection of these focus group participants was purposive to elicit ideas from the popular opinion leaders. Their opinions may not be generalizable to all secondary students in Mbarara or beyond. Findings are intended to offer a guide for similar programs in or planning development. In addition, the number of participants totaled 15 and the results comprise three focus groups. This is a relatively small number of participants. Nonetheless, we believe that obtaining information from the most popular youth in our study schools may be an efficient manner of obtaining feedback and can contribute in an important way to the development of a compelling Internet based program.

Together, findings from the three focus groups reported here has provided specific information and ideas for content to strengthen the CyberSenga program and make it compelling, interesting and attractive to the young people we hope to recruit for an evaluation of our CyberSenga program.

Acknowledgments

The CyberSenga project is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health, R01-MH080662. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We would like to thank the entire study team from Internet Solutions for Kids, Mbarara University of Science and Technology, University of Colorado, and Harvard University, who contributed to the planning and implementation of the study. Finally, we thank the adolescents and the partner schools for their time and willingness to participate in this study.

Reference List

- 1.World Health Organization. A global overview of the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. Kampala, Uganda: United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS); 2008. UNGASS COUNTRY PROGRESS REPORT UGANDA to UNAIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neema S, Ahmed F, Kibombo R, et al. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2006. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Uganda: results from the 2004 Uganda National Survey of Adolescents. Report No. 25. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ybarra M, Bull S. Current trends in Internet-based and cell-phone based HIV prevention and intervention programs. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2007;4:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology-based HIV prevention interventions: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009 Jan 2;23(1):107–115. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winzelberg A, Eldredge KL, Eppstein D, et al. Effectiveness of an Internet-based program for reducing risk factors for eating disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(2):346–350. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tate DF, Wing RR, Winett RA. Using Internet technology to deliver a behavioral weight loss program. JAMA. 2001 Mar 7;285(9):1172–1177. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.9.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Boberg EW, et al. CHESS-10 years of research and development in consumer health informatics for broad populations, including the underserved. International. Journal of Medical Informatics. 2002 Nov 12;65(3):169–177. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(02)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glasgow RE, Boles SM, McKay HG, et al. The D-Net diabetes self-management program: long-term implementation, outcomes, and generalization results. Prev Med. 2003 Apr;36(4):410–419. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vital Wave Consulting. Washington, DC: UN Foundation-Vodafone Foundation Partnership; 2009. mHealth for Development: The Opportunity of Mobile Technology for Healthcare in the Developing World. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiviat A, Geary M, Sunpath H, et al. HIV Online Provider Education (HOPE): the internet as a tool for training in HIV medicine. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(s):S512–S515. doi: 10.1086/521117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curioso WH, Kurth A. Access, use and perceptions regarding Internet, cell phones and PDAs as a means for health promotion for people living with HIV in Peru. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2007;7(24):9–12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau J, Lau M, Cheung A, et al. A randomized controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of an Internet-based intervention in reducing HIV risk behaviors among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. AIDS Care. 2008 doi: 10.1080/09540120701694048. 207820828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kibombo R, Neema S, Moore A, et al. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2008. Adults' Perceptions of Adolescents' Sexual and Reproductive Health: Qualitative Evidence from Uganda. Report No. 35. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neema S, Moore AM, Kibombo R. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2007. Adolescents' Sexual and Reproductive Health: Qualitative Evidence of Experiences from Uganda. Report No. 31. [Google Scholar]