Abstract

Background

The optimal strategy for oncologic sternectomy reconstruction has not been well characterized. We hypothesized that the major factors driving the reconstructive strategy for oncologic sternectomy include the need for skin replacement, extent of the bony sternectomy defect, and status of the internal mammary vessels.

Study Design

We reviewed consecutive oncologic sternectomy reconstructions performed at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center over a 10-year period. Regression models analyzed associations between patient, defect, and treatment factors and outcomes in order to identify patient and treatment selection criteria. We developed a generalized management algorithm based on these data.

Results

Forty-nine consecutive patients underwent oncologic sternectomy reconstruction (mean follow-up = 18±23 months). More sternectomies were partial (74%) rather than total/sub-total (26%). Most defects (N=40, 82%) required skeletal reconstruction. Pectoralis muscle flaps were most commonly employed for sternectomies with intact overlying skin (64%) and infrequently used when a presternal skin defect was present (36%; p=0.06). Free flaps were more often used for total/sub-total versus partial sternectomy defects (75% vs. 25%, respectively; p=0.02). Complication rates for total/sub-total sternectomy and partial sternectomy were equivalent (46% vs. 44%, respectively; p=0.92).

Conclusions

Despite more extensive sternal resections, total/sub-total sternectomies resulted in equivalent postoperative complications when combined with the appropriate soft tissue reconstruction. Good surgical and oncologic outcomes can be achieved with defect-characteristic-matched reconstructive strategies for these complex oncologic sternectomy resections.

INTRODUCTION

Although the sternum is an uncommon site for both primary and metastatic malignancies, resection of isolated sternal tumors with a total or partial sternectomy affords certain patients oncologic and symptomatic benefits.1,2 Oncologic sternal reconstruction frequently involves the placement of a rigid or semi-rigid skeletal prosthesis in the anterior chest wall to restore coordinated chest wall motion and protect the underlying mediastinum, along with an overlying soft tissue flap for prosthetic coverage and skin replacement. (Figure 1)

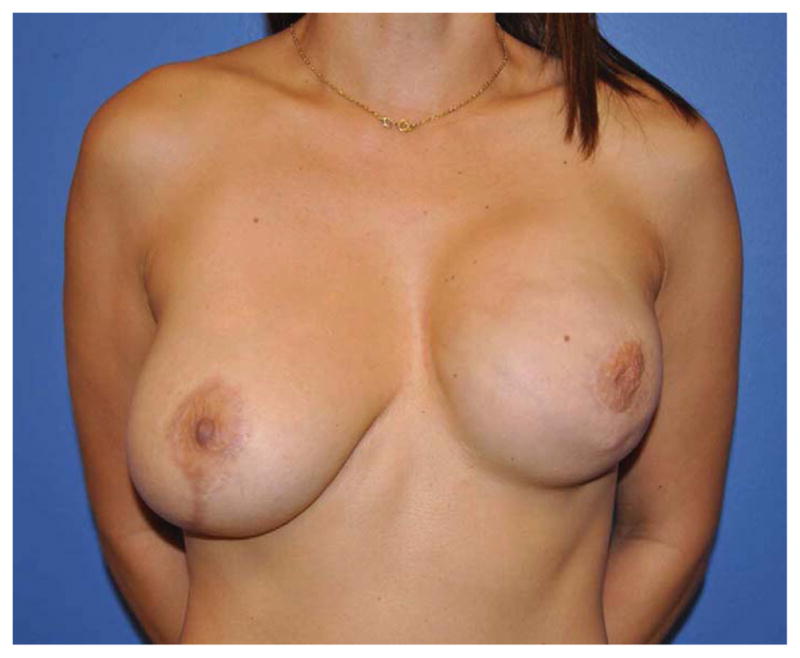

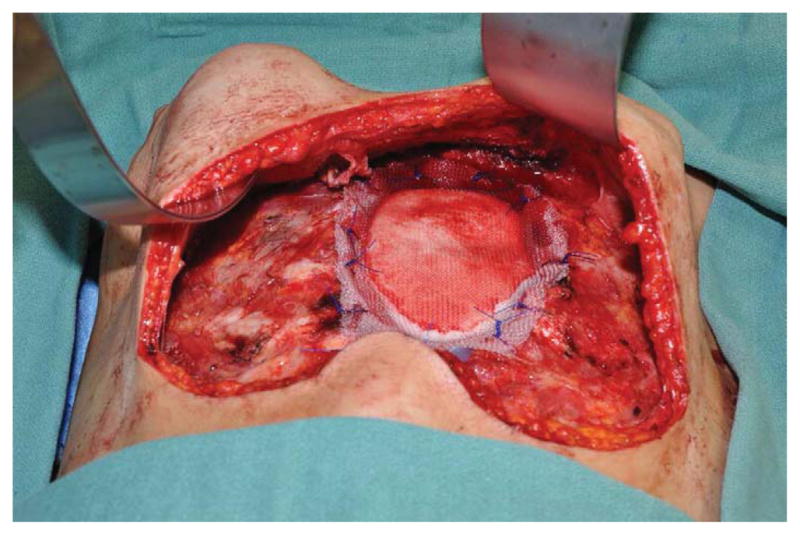

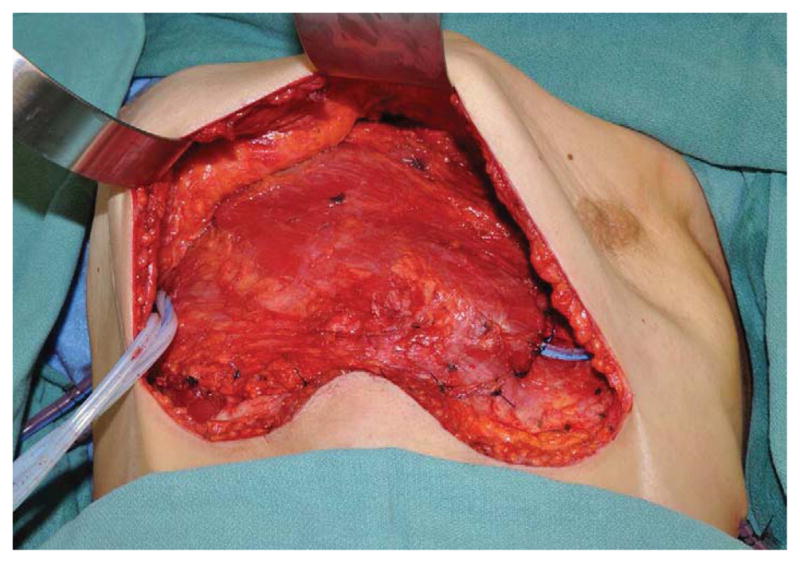

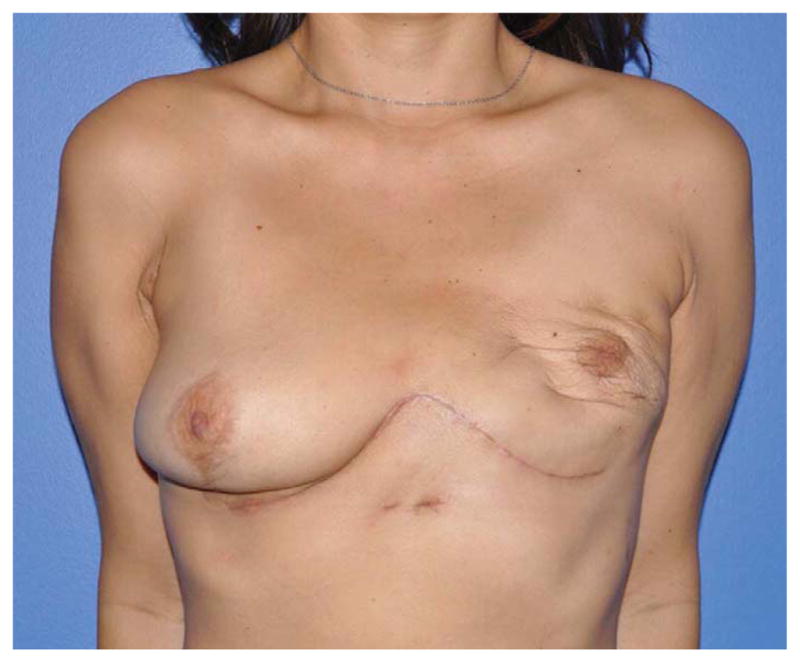

Figure 1.

(A) Example of a subtotal sternectomy reconstruction patient. A 40-year-old female presented with metastatic breast cancer to her left sternal body five years after having undergone a left mastectomy and immediate left breast implant reconstruction at an outside facility. (B) Intraoperative appearance after a manubrium-sparing subtotal sternectomy and PMM/PP prosthesis reconstruction. (C) Intraoperative appearance after defect coverage with a right pectoralis major muscle flap pedicled on the thoracoacromial artery. (D) Six-week postoperative appearance. (E) One-year postoperative appearance after 2-stage, tissue expander/implant breast reconstruction and contralateral augmentation.

Oncologic sternectomy defects and their reconstruction are fundamentally different than post-cardiac surgery wounds, which are caused by midline vertical sternotomies, are often infected, typically require serial debridement, and offer a predictably midline location. Oncologic sternectomies defects may be created anywhere in the sternal/coastal area, often involve resection of the overlying skin and/or sacrifice of the internal mammary (IM) vessels, and are not commonly infected. Furthermore, patients undergoing oncologic sternectomy typically present with a compromised capacity for wound healing secondary to adjuvant chemoradiation. Thus, oncologic sternectomy creates more heterogeneous clinical scenarios that demand a more comprehensive reconstructive strategy than is required for post-cardiac sternotomy wound reconstruction. However, a strategy for optimally managing oncologic sternectomy defects has yet to be adequately described.3–6 Given our experience at a high-volume cancer center with reconstructing these uncommon defects, we sought to develop an outcomes-based algorithm for sternal defects based on post-extirpative wound characteristics and surgical outcomes. We hypothesized that the major clinical factors impacting flap selection for oncologic sternectomy reconstructions would be the need for skin replacement, the extent of the bony sternectomy defect, and the status of the IM vessels.

METHODS

We retrospectively evaluated all consecutive patients who underwent immediate oncologic partial or total sternectomy reconstructions at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center between June 18, 2001 and January 25, 2012. Our Institutional Review Board approved this study. We included only patients who underwent reconstruction to repair an extirpative oncologic defect involving the sternum. We excluded patients treated for wounds that developed following a midline sternotomy performed to achieve cardiac or mediastinal exposure and patients who underwent delayed reconstruction for wounds that developed in prior sternectomy defects. We compared outcomes among patients with the three sternectomy characteristics that we believed to be the most critical factors determining choice of reconstruction and outcomes: 1) extent of skeletal defect (total/sub-total vs. partial sternectomy); 2) presence or absence of a skin defect; and 3) IM vessel status (both IM vessels intact vs. unilateral IM vessel sacrifice vs. bilateral IM vessel sacrifice). The primary outcome measures were the overall and specific complication rates and their relationship to these critical factors. Secondary outcome measures included oncologic recurrence and mortality and the correlation between resection characteristics and reconstructive options utilized by the surgeon. Finally, we sought to develop a management algorithm based on these data.

Patient, tumor, defect, and reconstructive factors were evaluated. Patient characteristics included smoking status, age, body mass index, gender, medical comorbidities, and cancer type. An active smoker was defined as a patient who smoked within one month of surgery. The type of cancer was divided into primary versus metastatic. Metastatic disease was further divided into breast primary tumors and non-breast primary tumors. Prior chest radiotherapy was noted. Defect characteristics included the size of the skeletal defect, presence or absence of a skin defect, and sacrifice of the IM vessels following tumor extirpation such that they were rendered unavailable to perfuse a regional flap. We classified the extent of sternal bone resection as partial, sub-total, or total. (Figure 2) A skin defect was defined as resection of the presternal skin that precluded primary coaptation without excessive tension. The area of the overlying skin defect was determined by pathologic and operative measurements. Reconstructive factors included the type of skeletal reconstruction and soft tissue replacement. In all cases the thoracic surgical oncologists performed both the sternectomy and skeletal reconstruction. The reconstructive surgeons then performed immediate soft tissue reconstruction of the sternal defect.

Figure 2.

Authors’ classification for types of oncologic sternectomies. The top row depicts a partial (Type I) sternectomy. The middle row demonstrates (from left to right) a Type IIA subtotal sternectomy sparing the manubrium, a Type IIB subtotal sternectomy sparing the xiphisternum, and a Type IIC vertical hemi-sternectomy. The bottom row provides an example of a total (Type III) sternectomy. (Reprinted from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, with permission.)

The overall complication rate was defined as the proportion of patients who developed at least one of the following complications: wound separation, cellulitis, abscess, hematoma, seroma, mesh removal, prolonged ventilator support (>24 hours), pulmonary embolus, or inhospital mortality. Wound separation was defined as a separation of at least 0.5 cm requiring debridement, healing by secondary intention, and/or surgical revision. An abscess was defined as a purulent fluid collection requiring incision and drainage. Cellulitis included erythema at the wound site that resolved with intravenous or oral antibiotics alone. Hematoma and seroma were defined as subcutaneous collections of blood or serous fluid, respectively, that required percutaneous or operative drainage. Pulmonary embolus was defined as a venous thromboembolic event that was symptomatic and confirmed radiographically.

Patients were generally followed up in the outpatient clinic weekly for 1 month after discharge, every 3 months for 6 months, and then yearly thereafter. In addition to serial physical examination, postoperative oncologic surveillance, with or without chest computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging, was used to evaluate surgical outcomes. Oncologic recurrence was defined as the reappearance of a tumor after its previous removal.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized the data using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. We examined the associations of overall complications with patient, tumor, defect, and reconstructive characteristics through univariate logistic regression modeling. Recurrence rates and the associations between type of reconstruction and skin defect and skeletal defect were examined using the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The survival difference was examined for each categorical characteristic using the log-rank test, and the assumption of proportionality of the survival functions among groups was examined using the Kaplan-Meier curve. Univariate Cox proportional hazard regression was used to assess a significant survival difference by each categorical variable, if the assumption of proportionality was satisfied for that variable. For continuous characteristic variables, univariate Cox proportional hazard regression was used to assess the effect on mortality. Univariate Cox proportional hazard models were utilized to examine the associations of each patient characteristic with hazard (death), if assumption of proportionality of survival function was satisfied through the Kaplan-Meier curve. We used SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) to perform the analyses. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

We identified 49 consecutive patients who underwent 49 sternectomies during the study period, with a mean patient follow-up of 18±23 months. The majority of patients (n=35, 71%) were female. The most common indication for sternectomy was resection of a metastatic tumor (Table 1). Over half (53%) of the patients had received radiotherapy to the sternal area prior to resection.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Data (n = 49) |

|---|---|

| Mean age, y | 52 ± 15 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 35 (71%) |

| Male | 14 (29%) |

| Mean body mass index, kg/m2 | 26 ± 7 |

| Indication for sternectomy, n (%) | |

| Metastatic tumor | 31 (63) |

| Breast cancer | 22 (71) |

| Lung cancer | 2 (6) |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 2 (6) |

| Malignant melanoma | 1 (3) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 (3) |

| Liposarcoma | 1 (3) |

| Thymic carcinoma | 1 (3) |

| Germ cell carcinoma | 1 (3) |

| Primary tumor | 12 (24) |

| Sarcoma | 10 (83) |

| Desmoid tumor | 2 (17) |

| Osteoradionecrosis | 6 (12) |

| Active smoker, n(%) | 8 (16) |

| Prior direct sternal radiation, n(%) | 26 (53) |

| At least one medical comorbidity, n(%) | 20 (41) |

Defect Characteristics

Table 2 demonstrates the characteristics of the sternal defects. Most of the resections were partial (n=36, 73%) rather than total/sub-total (n=13, 26%) sternectomies. Over half of the resections included a skin resection overlying the sternectomy skeletal defect. One third of the patients’ resections required sacrifice of both of the IM vessels.

Table 2.

Defect Details

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| n | 49 | |

| Sternectomy type | ||

| Total/near total sternectomy | 13 | 26 |

| Partial sternectomy | 36 | 73 |

| Skin defect present | 29 | 59 |

| IMA Status | ||

| Both IMAs intact | 13 | 26 |

| One IMA intact | 20 | 41 |

| Neither IMA intact | 15 | 31 |

IMA, internal mammary artery.

Reconstruction Strategy

The vast majority (n=40, 82%) of the skeletal defects resulting from the sternectomy required some form of structural skeletal reconstruction (Table 3). The majority of patients (85%) undergoing a total or sub-total sternectomy received some form of synthetic skeletal reconstruction: a polymethylmethacrylate/polypropylene (PMM/PP) implant, polypropylene (PP) or polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) synthetic mesh alone, or L-lactide-co-glycolide copolymer rapidly resorbable mesh fixation system (RRFS) (Table 4). Two of the three RRFS reconstructions were employed for total sternectomy defects. There were more semi-rigid (i.e., Acellular dermal matrix [ADM], PP, PTFE, RRFS) reconstructions (n=22, 45%) performed than rigid (i.e., PMM/PP) reconstructions (n=18, 37%). The skeletal defect was significantly predictive of the type of soft tissue reconstruction performed. Forty-two (86%) of the patients received some form of soft tissue flap coverage of their sternectomy defects (Table 5). Free flaps were more often used for total/sub-total sternectomy defects than for partial sternectomy defects (46% vs. 6%, respectively; p=0.02).

Table 3.

Reconstruction of the Osseous Sternectomy Defect

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| n | 49 | |

| Rigid reconstruction | ||

| PMM/PP | 18 | 37 |

| Semi-rigid reconstruction | ||

| Synthetic mesh (PP or PTFE) | 14 | 29 |

| ADM | 5 | 10 |

| RRFS | 3 | 6 |

| Neither rigid nor semi-rigid reconstruction | 9 | 18 |

PMM/PP, polymethylmethacrylate/polypropylene sandwich; PP, polypropylene; PTFE, polytetrafluoroethylene; ADM, acellular dermal matrix; RRFS, L-lactide-co-glycolide copolymer rapidly resorbable fixation system.

Table 4.

Relationship between Defect Characteristics and Skeletal Reconstructive Choices

| Variable | PP + MM | PP or PTFE | ADM | RRFS | None | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal defect | ||||||

| Total/sub-total sternectomy | 5 (28%) | 4 (29%) | 1 (20%) | 2 (67%) | 1 (11%) | 0.49 |

| Partial sternectomy | 13 (72%) | 10 (71%) | 4 (80%) | 1 (33%) | 8 (89%) | |

| Skin defect | ||||||

| Yes | 9 (50%) | 11 (79%) | 3 (60%) | 2 (67%) | 4 (44%) | 0.44 |

| No | 9 (50%) | 3 (21%) | 2 (40%) | 1 (33%) | 5 (56%) | |

| IMA Status | ||||||

| Both IMA intact | 4 (22%) | 3 (21%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (56%) | 0.49 |

| Bilateral IMA sacrifice | 7 (39%) | 6 (43%) | 2 (50%) | 3 (100%) | 2 (22%) | |

| Unilateral IMA sacrifice | 7 (39%) | 5 (36%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (22%) |

PP, polypropylene; MM, methylmethacrylate; PTFE, polytetrafluoroethylene; ADM, acellular dermal matrix; RRFS, L-lactide-co-glycolide copolymer rapidly resorbable fixation system; IMA, internal mammary artery.

Table 5.

Reconstruction of the Soft Tissue Sternectomy Defect

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| n | 49 | |

| Pectoralis major muscle/musculocutaneous flap | 22 | 45 |

| Free fap | 8 | 16 |

| VRAM | 3 | 37 |

| TRAM | 2 | 25 |

| ALT | 2 | 25 |

| LD | 1 | 12 |

| Rectus Abdominis-based Flap | 7 | 14 |

| Omental flap | 5 | 10 |

| Fasciocutaneous flap advancement | 7 | 14 |

VRAM, vertical rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap; TRAM, transverse rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap; ALT, anterolateral thigh flap; LD, latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap.

The presence or absence of a skin defect significantly influenced the choice of soft tissue reconstruction. Pectoralis muscle flaps were most commonly employed for resections with intact overlying skin (64%) and infrequently used when a skin defect was present (36%; p=0.06). When a skin defect was present, free flaps, omental flaps, rectus-based flaps, and fasciocutaneous advancements were more often employed (Table 6). All but one of the patients’ IMA statuses was able to be determined. Differences in flap use by IMA status were not significant. Seven (14%) patients received local-advancement fasciocutaneous flap coverage of the defect whereby the local skin and subcutaneous tissue were mobilized with surgical undermining and advanced to achieve primary closure without the inclusion of an underlying or adjacent muscle, musculocutanous, or omental flap.

Table 6.

Relationship between Defect Characteristics and Soft Tissue Reconstructive Choices

| Variable | Free Flap | Omental Flap | Pectoralis Flap | Rectus Abdominis-Based Flap | Other Flaps | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skeletal defect | ||||||

| Total/sub-total sternectomy | 6 (75%) | 1 (20%) | 3 (14%) | 1 (14%) | 2 (29%) | 0.02 |

| Partial sternectomy | 2 (25%) | 4 (80%) | 19 (86%) | 6 (86%) | 5 (71%) | |

| Skin defect | ||||||

| Yes | 7 (87%) | 4 (80%) | 8 (36%) | 5 (71%) | 5 (71%) | 0.06 |

| No | 1 (12%) | 1 (20%) | 14 (64%) | 2 (29%) | 2 (29%) | |

| IMA Status | ||||||

| Both IMA intact | 2 (25%) | 2 (40%) | 6 (29%) | 3 (43%) | 0 (0%) | 0.28 |

| Bilateral IMA sacrifice | 2 (25%) | 3 (60%) | 9 (43%) | 1 (14%) | 5 (71%) | |

| Unilateral IMA sacrifice | 4 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (29%) | 3 (43%) | 2 (29%) |

IMA, internal mammary artery.

Postoperative Outcomes

Overall, 38% of patients experienced at least one postoperative complication (Table 7). Most of the complications were managed conservatively, with only four (8%) patients requiring re-operation. These re-operations included two hematoma evacuations in patients with flaps overlying PMM/PP implants, a diaphragmatic hernia repair following an omental flap overlying RRFS, and a patient who had undergone a PMM/PP implant without flap coverage at an outside hospital and had subsequently received postoperative radiotherapy. This fourth patient presented to our institution with PMM/PP exposure that necessitated prosthesis removal and reconstruction with bilateral pectoralis muscle flaps.

Table 7.

Postoperative Complications

| Complication | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| n | 49 | |

| Wound separation | 11 | 22 |

| Cellulitis | 4 | 8 |

| Hematoma | 4 | 8 |

| Seroma | 2 | 4 |

| Mesh removal | 1 | 2 |

| Prolonged ventilatory support | 1 | 2 |

| Pulmonary embolus | 1 | 2 |

| In-hospital mortality | 1 | 2 |

Patients with at least 1 medical co-morbidity had a higher incidence of complications (60%) compared to patients with no medical co-morbidities (34%), but the difference was not significant (p=0.08; Table 8). There were no specific co-morbidities or reconstruction characteristics that were predictive of complications on univariate regression analysis. (Tables 8 and 9) Complication rates were similar between patients even in the setting of more extensive resections (total/sub-total vs. partial sternectomies), skin defects, or IM vessel sacrifice.

Table 8.

Univariate Logistic Regression Model of Patient and Defect Characteristics by Presence or Absence of Complications

| Characteristic | Complications | Univariate Logistic Regression Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=22) | No (n=27) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Mean age, y | 55 ± 17 | 49 ± 11 | 1.0 (0.98–1.1) | 0.18 |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 | 26 ± 7 | 27 ± 7 | 1.0 (0.90–1.1) | 0.60 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 14 (40%) | 21 (60%) | 0.5 (0.14–1.8) | 0.28 |

| Male | 8 (57%) | 6 (43%) | Ref. | - |

| Cancer type | ||||

| Metastatic | 13 (42%) | 18 (58%) | 1.0 (0.26–3.1) | 0.99 |

| Primary | 5 (42%) | 7 (58%) | Ref. | - |

| Cancer type sub-analysis | ||||

| Metastatic breast | 7 (32) | 15 (68) | 0.7 (0.15–2.8) | 0.57 |

| Metastatic other | 6 (67) | 3 (33) | 2.8 (0.47–16.9) | 0.26 |

| Primary | 5 (42) | 7 (58) | Ref. | - |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Active smoker | 4 (50%) | 4 (50%) | 1.3 (0.28–5.8) | 0.75 |

| Nonsmoker | 18 (44%) | 23 (56%) | Ref. | - |

| History of radiotherapy | ||||

| Yes | 12 (46%) | 14 (54%) | 1.1 (0.36–3.4) | 0.85 |

| No | 10 (43%) | 13 (57%) | Ref. | - |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| ≥1 Medical comorbidity | 12 (60%) | 8 (40%) | 2.9 (0.88–9.2) | 0.08 |

| No medical comorbidities | 10 (34%) | 19 (66%) | Ref. | - |

| Skeletal defect | ||||

| Total/sub-total sternectomy | 6 (46%) | 7 (54%) | 1.1 (0.31–4.1) | 0.92 |

| Partial sternectomy | 16 (44%) | 20 (56%) | Ref. | - |

| Skin defect | ||||

| Yes | 12 (41%) | 17 (59%) | 0.7 (0.22–2.22) | 0.55 |

| No | 10 (50%) | 10 (50%) | Ref. | - |

| IMA status | ||||

| Both IMA intact | 5 (39%) | 8 (61%) | 1.3 (0.27–5.9) | 0.78 |

| Bilateral IMA sacrifice | 11 (55%) | 9 (45%) | 2.4 (0.61–9.80) | 0.21 |

| Unilateral IMA sacrifice | 5 (33%) | 10 (67%) | Ref. | - |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; IMA, internal mammary artery.

Table 9.

Univariate Logistic Regression Model of Reconstruction Characteristics by Presence or Absence of Complications

| Characteristic | Complications | Univariate Logistic Regression Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=22) | No (n=27) | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Mesh type | ||||

| PP + MM | 8 (44%) | 10 (56%) | 0.7 (0.09–4.2) | 0.89 |

| PP or PTFE | 4 (29%) | 10 (71%) | 0.3 (0.04–2.5) | 0.39 |

| ADM | 2 (40%) | 3 (60%) | 0.6 (0.03–7.7) | 1.00 |

| RRFS | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 2.4 (0.2-infinity) | 0.51 |

| None | 5 (56%) | 4 (44%) | Ref. | - |

| Flap type | ||||

| Free flap | 3 (37%) | 5 (63%) | 1.5 (0.17–13.2) | 0.71 |

| Omental flap | 3 (60%) | 2 (40%) | 3.8 (0.33–42.5) | 0.29 |

| Pectoralis flap | 9 (41%) | 13 (59%) | 1.7 (0.27–11.0) | 0.56 |

| Fasciocutanous flap advancement | 5 (71%) | 2 (29%) | 6.3 (0.62–63.5) | 0.12 |

| Rectus abdominis-based flaps | 2 (29%) | 5 (71%) | Ref. | - |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PP, polypropylene; MM, methylmethacrylate; PTFE, polytetrafluoroethylene; ADM, acellular dermal matrix. RRFS, L-lactide-co-glycolide copolymer rapidly resorbable fixation system

The oncologic mortality rate was 49%, with an overall median survival time of 18 months for the study population. Univariate logistic regression analysis of patient mortality demonstrated significantly worse survival for patients undergoing operations for metastatic disease compared to primary tumors (excluding osteoradionecrosis patients) (HR 6.0; p=0.02) (Table 10). Compared to the mortality rate for primary tumors, the oncologic mortality rate was significantly higher for sternectomy patients with metastatic breast cancer (50%; p=0.05) and highest for patients with metastatic cancer from sources other than the breast (89%; p=0.001). Metastatic tumors from a source other than the breast resulted in significantly worse survival outcomes (11% alive; HR 14.4) when compared to metastatic breast (50% alive; HR 4.5) or primary sternal tumors (83% alive; p=0.0005) (Table 10). Recurrence rate, while lower in total/sub-total sternectomies (n=4; 33% recurrence) when compared to partial sternectomies (n=18, 60%), did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference (p=0.12). The mortality rate in patients who underwent total/sub-total sternectomies was also lower (67% alive) when compared to those who had partial sternectomies (45% alive), though this difference did not reach significance (p=0.10) (Table 10). Multivariate regression analysis could not be performed because no factors were significantly associated with complications and only cancer type was found to be significantly associated with mortality on univariate analysis.

Table 10.

Univariate Logistic Regression Model of Patient and Defect Characteristics by Mortality

| Characteristic | Mortality | Univariate logistic regression model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deceased (n=21) | Alive (n=22) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Cancer type | 0.06 | ||||

| Metastatic | 19 (61) | 12 (39) | 6.1 (1.4–26.2) | 0.02 | |

| Primary | 2 (17) | 10 (83) | Ref. | ||

| Cancer type subanalysis | 0.0005 | ||||

| Metastatic breast | 11 (50) | 11 (50) | 4.5 (0.99–20.5) | 0.05 | |

| Metastatic other | 8 (89) | 1 (11) | 14.4 (2.9–73.0) | 0.001 | |

| Primary | 2 (17) | 10 (83) | Ref. | ||

| Skeletal defect | 0.13 | ||||

| Total/Sub-total sternectomy | 4 (33) | 8 (67) | 0.40 (0.14–1.2) | 0.10 | |

| Partial sternectomy | 17 (55) | 14 (45) | Ref. | ||

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

In this study representing the largest comprehensive evaluation of reconstructions of oncologic sternectomy defects to date, we demonstrated that the overall complication rates for reconstructions of partial and total/sub-total sternectomies were equivalent. Given the trend towards more aggressive resections affording patients superior oncologic outcomes, it is important to realize that equivalent complication rates can be realized if an appropriate reconstruction is provided. We confirmed our hypothesis that the most influential factors to be considered in approaching these defects are the extent of the skeletal defect and the presence or absence of an overlying skin defect. As these factors worsen, they drive the reconstructive strategy away from local fasciocutaneous flaps towards regional and free flaps. These data combined with our collective experience over this time period have allowed us to develop a reconstructive strategy that is specific to oncologic sternectomy defects, involving progressively more complex reconstructions based on the magnitude of skeletal and skin resection and the status of the IM vessels. (Figure 3) This approach is no longer derivative of what has been described for cardiac sternotomy wounds.

Figure 3.

Oncologic sternectomy reconstruction algorithm. U/L, unilateral; B/L, bilateral; Pec, pectoralis muscle; TA, thoracoacromial artery; IM, internal mammary artery; VRAM, vertical rectus abdominis musculocutaneous flap.

It appears that pre-sternal soft tissue reconstruction as an adjunct to the skeletal prosthetic reconstruction may mitigate the potential for complications associated with oncologic sternectomies. Indeed, we observed higher complication rates in sternectomies that received only fasciocutaneous skin flap advancement, particularly when associated with preoperative or postoperative radiotherapy. These findings have validated how our clinical practice has evolved over time in that we progressively became more liberal in our employment of soft tissue flaps overlying the skeletal defects due to the fact that the patients with flaps seemed to experience fewer complications than those without flaps. Selecting the optimal option for soft tissue coverage appears to be chiefly determined by the need for skin replacement. Pectoralis muscle flaps were the most commonly used flaps in this series, but the majority of the pectoralis muscle flap reconstructions did not require skin replacement. When a skin defect existed, omental flaps, rectus abdominis flaps, and free flaps were favored over pectoralis flaps. Among sternectomies with a skin defect, the decision to perform a free flap was also influenced by the extent of the skeletal defect. We saw that the majority of the free flaps were performed when skin replacement was necessary in the setting of total/sub-total sternectomies. The exposure of the IM recipient vessels afforded by a total/sub-total sternectomy may explain this observation, as all of the free flaps were anastomosed to the IM vessels.

In the setting of sub-total and total sternectomies, our thoracic surgeons favored a rigid skeletal reconstruction using a PMM/PP “sandwich” technique. Although we were concerned that placement of this prosthesis might result in higher infectious complications, particularly in irradiated wounds, it appears that this is safe when the prosthesis is combined with an overlying vascularized soft tissue flap. However, all but one of the PMM/PP reconstructions in this series included an overlying flap, so we cannot definitively determine whether the rate of complications would have been higher if the overlying skin was simply closed without flap coverage. The one patient that did not receive an overlying flap did develop PMM/PP exposure after radiation necessitating prosthesis removal and reconstruction with bilateral pectoralis major muscle flaps, an outcome that affected our later decision-making in terms of more frequent use of flaps in the setting of radiation therapy. The use of PMM/PP has historically been used to improve chest physiology and prevent paradoxical motion during respiration for more lateral chest wall defects7,8, but the extent of sternectomy resection that mandates a rigid vs. semi-rigid prosthesis remains to be determined. Our surgeons more liberally used PMM/PP early in this patient series. With the availability of bioprosthetics, our encouraging results with bioprosthetics in complex abdominal wall reconstruction,9–11 and our encouraging results with semi-rigid reconstruction for partial sternectomy defects, our surgeons shifted to more selectively employing rigid PMM/PP for extensive central sternectomy defects (e.g. total/sub-total sternectomies) and semi-rigid bioprosthetic or PP mesh for less extensive partial sternectomies.

The use of radiotherapy did not significantly affect the overall complication rate in this study. This may be explained by reconstructive decision-making, as the majority of the irradiated sternectomy wounds received an overlying soft tissue flap reconstruction. Only two patients received local fasciocutaneous tissue rearrangement for soft tissue reconstruction in the presence of preoperative radiation, and both of these patients developed post-operative wound healing complications. In contradistinction, satisfactory results were realized when muscle, musculocutaneous, or omental flaps were employed in the setting of prior radiation. Given these data, we discourage primary closure or fasciocutaneous flaps in the setting of prior radiotherapy.

Traditionally, synthetic mesh has been the most common means of achieving semi-rigid reconstruction, but some of our patients received ADM, which has shown promising results in abdominal wall reconstruction9–11, particularly in the setting of a contaminated wound. We observed satisfactory outcomes for the sternectomy defects reconstructed with ADM, with complication rates similar to the synthetic mesh reconstructions, but whether ADM has significant advantages over synthetic mesh for thoracic reconstruction is beyond the scope of this study and warrants further investigation. It is noteworthy that all three of the RRFS reconstructions in this study developed complications. RRFS was employed early in the study period, but our thoracic surgeons grew dissatisfied with the material and ultimately abandoned its use due to the associated high complication rate and inadequate structural integrity over time. Our surgeons also abandoned PTFE due to lack of incorporation and seroma formation.

Although the patients’ IM vessel status did not significantly correlate with the choice of reconstruction, we did observe trends that suggest our reconstructive surgeons did consider the IMA status. Absence of at least one intact IM vessel seemed to discourage the use of a pedicled rectus abdominis flap or a pectoralis turnover flap, flaps that are both primarily dependent upon intact ipsilateral IM vessels. All of the free flaps in this series were anastomosed to the IM vessels. Even with bilateral IM sacrifice, IM vessels can still serve as recipient vessels as long as the ablative surgeon is able to leave enough vessel length for microvascular anastomosis. Indeed, two patients in this series with bilateral IM sacrifice were still able to undergo successful free flap reconstruction to the IM vessels. However, if the resection renders both IM vessels unusable as recipient vessels, either alternate recipient vessels or an omental flap should be considered.

As might be expected, tumor type had the largest impact on oncologic outcomes. Resection of primary sternal tumors appears to be particularly warranted, given the favorable outcomes demonstrated in our study and other studies.12–17 However, the treatment of advanced breast cancer remains a more controversial topic. Our center’s aggressive surgical approach to metastatic breast cancer of the sternum appears to be justified given that half of the patients who underwent sternectomy and reconstruction for metastatic breast cancer survived. Patients with metastatic disease from a source other than the breast experienced the highest mortality and complication rates. In light of these findings, it is imperative that the optimal reconstructive strategy be chosen should sternectomy become necessary for this at-risk subgroup.

The advantages of this study include its being the largest to report purely oncologic sternectomy reconstructions, the focus on reconstruction choices and outcomes, the diversity of oncologic diagnoses, and the use of consecutive patients. Limitations are that it is underpowered for some comparisons, has the potential for surgical bias due to the study’s retrospective design, and has limited follow-up in some patient groups due to the high mortality rate experienced by these patients. Retrospective design and study size also precluded evaluation of pulmonary function and functional analysis of rigid versus semi-rigid skeletal reconstruction.

As has been previously demonstrated16,17, we found in this series that more extensive sternal resections resulted in satisfactory oncologic outcomes with equivalent postoperative complications when combined with the appropriate soft tissue flap reconstruction. The status of the overlying skin and the extent of the skeletal resection appear to be the most important factors to consider when formulating a reconstructive strategy. Although the status of the IM vessels was not demonstrated to be statistically associated with the choice of reconstruction or patient outcomes, the IM vessel status did appear to affect the approach to these defects. When faced with reconstruction of these complex sternectomy resections, surgeons should consider the status of the skeletal defect, the need for skin replacement, prior or planned radiotherapy, and the status of the IM vessels. (Figure 3)

CONCLUSION

Combining an appropriate soft tissue reconstruction with reconstruction of the underlying sternectomy skeletal defect allows even total sternectomies to be performed with acceptably low morbidity. The needs of patient should be assessed on an individual basis, and a collaborative effort on behalf of the ablative and reconstruction surgeons is imperative to provide the optimal management for these patients.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672.

The authors thank Michael Gallagher from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Department of Medical Graphics and Photography for contributing scientific illustrations and Dawn Chalaire from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Department of Scientific Publications for assistance with scientific editing. The authors also wish to recognize current and former MD Anderson Plastic Surgeons for their contribution of clinical experience to this series: Drs David Adelman, Elisabeth Beahm, David Chang, Edward Chang, Pierre Chevray, Melissa Crosby, Mennen Gallas, Matthew Hanasono, Lior Heller, Steven Kronowitz, Michael Miller, Scott Oates, Gregory Reece, Geoffrey Robb, Roman Skoracki, Mark Villa, and Peirong Yu.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADM

Acellular Dermal Matrix

- IM

Internal Mammary

- PMM/PP

Polymethylmethacrylate/Polypropylene

- PP

Polypropylene

- PTFE

Polytetrafluoroethylene

- RRFS

L-lactide-co-glycolide Copolymer Rapidly Resorbable Fixation System

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Dr Garvey receives fees for consulting for Lifecell Corporation. All other authors have nothing to disclose.

Presented at the American College of Surgeons 98th Annual Clinical Congress, Chicago, IL, October 2012

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Noguchi S, Miyauchi K, Nishizawa Y, et al. Results of surgical treatment for sternal metastasis of breast cancer. Cancer. 1988;62:1397–401. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19881001)62:7<1397::aid-cncr2820620726>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carbognani P, Vagliasindi A, Costa P, et al. Surgical treatment of primary and metastatic sternal tumours. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2001;42:411–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pairolero PC, Arnold PG, Harris JB. Long-term results of pectoralis major muscle transposition for infected sternotomy wounds. Ann Surg. 1991;213:583–589. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199106000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pairolero PC, Arnold PG. Management of recalcitrant median sternotomy wounds. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984;88:357–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jurkiewicz MJ, Bostwick J, 3rd, Hester TR, et al. Infected median sternotomy wound. Successful treatment by muscle flaps. Ann Surg. 1980;191:738–744. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198006000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones G, Jurkiewicz MJ, Bostwick J, et al. Management of the infected median sternotomy wound with muscle flaps. The Emory 20-year experience. Ann Surg. 1997;225:766–776. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199706000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilic D, Gungor A, Kavukcu S, et al. Comparison of mersilene mesh-methyl metacrylate sandwich and polytetrafluoroethylene grafts for chest wall reconstruction. J Invest Surg. 2006;19:353–360. doi: 10.1080/08941930600985694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weyant MJ, Bains MS, Venkatraman E, et al. Results of chest wall resection and reconstruction with and without rigid prosthesis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:279–85. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butler CE, Campbell KT. Minimally invasive component separation with inlay bioprosthetic mesh (MICSIB) for complex abdominal wall reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:698–709. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318221dcce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell KT, Burns NK, Rios CN, et al. Human versus non-cross-linked porcine acellular dermal matrix used for ventral hernia repair: comparison of in vivo fibrovascular remodeling and mechanical repair strength. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2321–2332. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318213a053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garvey PB, Bailey CM, Baumann DP, et al. Violation of the rectus complex is not a contraindication to component separation for abdominal wall reconstruction. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martini N, Huvos AG, Burt ME, et al. Predictors of survival in malignant tumors of the sternum. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;111:96–105. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briccoli A, Manfrini M, Rocca M, et al. Sternal reconstruction with synthetic mesh and metallic plates for high grade tumours of the chest wall. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:494–499. doi: 10.1080/110241502321116523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soysal O, Walsh GL, Nesbitt JC, et al. Resection of sternal tumors: extent, reconstruction, and survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1353–1358. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00641-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh GL, Davis BM, Swisher SG, et al. A single-institutional, multidisciplinary approach to primary sarcomas involving the chest wall requiring full-thickness resections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:48–60. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.111381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lequaglie C, Massone PB, Giudice G, Conti B. Gold standard for sternectomies and plastic reconstructions after resections for primary or secondary sternal neoplasms. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:472–479. doi: 10.1007/BF02557271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girotti P, Leo F, Bravi F, et al. The “rib-like” technique for surgical treatment of sternal tumors: lessons learned from 101 consecutive cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1208–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]