Abstract

The role of microsomal cytochrome b5 (Cyb5) in defining the rate of drug metabolism and disposition has been intensely debated for several decades. Recently we described mouse models involving the hepatic or global deletion of Cyb5, demonstrating its central role in in vivo drug disposition. We have now used the cytochrome b5 complete null (BCN) model to determine the role of Cyb5 in the metabolism of ten pharmaceuticals metabolised by a range of cytochrome P450s, including five anti-cancer drugs, in vivo and in vitro. The extent to which metabolism was significantly affected by the absence of Cyb5 was substrate-dependent, with AUC increased (75-245%), and clearance decreased (35-72%), for phenacetin, metoprolol and chlorzoxazone. Tolbutamide disposition was not significantly altered by Cyb5 deletion, while for midazolam clearance was decreased by 66%. The absence of Cyb5 had no effect on gefitinib and paclitaxel disposition, while significant changes in the in vivo pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide were measured (Cmax and terminal half-life increased 55% and 40%, respectively), tamoxifen (AUClast and Cmax increased 370% and 233%, respectively) and anastrozole (AUC and terminal half-life increased 125% and 62%, respectively; clearance down 80%). These data from provide strong evidence that both hepatic and extra-hepatic Cyb5 levels are an important determinant of in vivo drug disposition catalysed by a range of cytochrome P450s, including currently-prescribed anti-cancer agents, and that individuality in Cyb5 expression could be a significant determinant in rates of drug disposition in man.

Introduction

Microsomal cytochrome b5 (Cyb5) is a 15.2kDa haemoprotein, which together with its electron donor cytochrome b5 reductase, is localised in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes and other cell types (Remacle et al., 1976). This enzyme system is involved in many metabolic pathways including steroid hormone and glucocorticoid biosynthesis, fatty acid desaturation and the reduction of methaemoglobin (Jeffcoat et al., 1977; Lamb et al., 2001; Akhtar et al., 2005; Umbreit, 2007; McLaughlin et al., 2010; Finn et al., 2011). In addition, Cyb5 donates electrons into the cytochrome P450 (P450) system as well as causing allosteric modification of P450 isozymes, resulting in either increased or reduced drug metabolism (Waskell et al., 1986; Yamazaki et al., 1996; Lamb et al., 2001; Porter, 2002; Yamazaki et al., 2002; Schenkman and Jansson, 2003; Yamaori et al., 2003; Akhtar et al., 2005; Finn et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008; McLaughlin et al., 2010).

It has been proposed that up to 30% of drug metabolism occurs in tissues other than the liver (Ding and Kaminsky, 2003). This has been supported by experiments using hepatic cytochrome P450 reductase null (HRN) mice, which are essentially devoid of hepatic P450-mediated drug metabolism; in this model, significant rates of metabolism for many drugs can still be observed in vivo (Henderson et al., 2003; Pass et al., 2005; Gu et al., 2007). To clarify the in vivo role of Cyb5 we have previously generated murine models of hepatic (Hepatic Cyb5 Null (HBN - Cyb5lox/lox::CreALB)) and complete Cyb5 deletion (Cyb5 Complete Null (BCN - Cyb5−/−)) (Finn et al., 2008; McLaughlin et al., 2010; Finn et al., 2011). Interestingly, the effects of Cyb5 on either in vitro or in vivo cytochrome P450-mediated drug disposition are highly substrate-and P450-specific (Porter, 2002; Yamazaki et al., 2002; Schenkman and Jansson, 2003; Yamaori et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2005; Finn et al., 2008; McLaughlin et al., 2010). Cyb5 is also reported to be an important determinant of extra-hepatic cytochrome P450 activities, although its role remains poorly defined (Kominami et al., 1992; Arinc et al., 1994; McLaughlin et al., 2010).

In this study we have used the BCN model, where Cyb5 is deleted in all tissues, to study the role of this enzyme in the in vivo disposition of a panel of pharmaceutical drugs, which includes five commonly prescribed anti-cancer drugs and further demonstrate its importance in hepatic and extra-hepatic drug metabolism.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

All reagents, unless otherwise stated, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK). NADPH was obtained from Melford Laboratories (Ipswich, UK). Cyclophosphamide, anastrozole (Arimidex) was obtained from Nova Laboratories (Wigston, UK), AstraZeneca (Luton, UK) and IPS(A) (Cheshire, UK) respectively.

Animal husbandry

Heterozygous Cyb5 null mice (Cytb5+/−) were maintained on a mixed 129×C57BL/6 background by random breeding with a corresponding, matched, wild-type (WT; Cytb5+/+) counterpart as previously described (Finn et al., 2008; McLaughlin et al., 2010). BCN mice (Cytb5−/−) and WT controls were both generated from a number of crosses: inter-crossing Cytb5+/− mice, by crossing BCN mice together, and by crossing Cytb5+/− with Cytb5−/− mice. Mice carrying the null cytochrome Cyb5 allele were identified by multiplex PCR using the following primer set: wild-type forward primer, 5′-TCCCCCT-GAGAACGTAATTG-3′; null forward primer, 5′-GGTCTCTCCTTG- GTCCACAC-3′; and common reverse primer, 5′-GAGTCTTCGTCAGT- GCGTGA-3′ (McLaughlin et al., 2010). All mice were maintained on a standard animal diet (RM1; Special Diet Services, Essex, UK) under standard animal house conditions, with free access to food and water, and 12h light/12h dark cycle. Animal work was carried out in accordance with the Animal (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986) after local ethical review.

Experimental Procedures

In vivo pharmacokinetics: drug cocktail

Male BCN mice and wild-type controls aged 8-12 weeks were dosed by oral gavage with a five-drug cocktail comprising phenacetin (5mg/kg), tolbutamide (5mg/kg), metoprolol (2mg/kg), chlorzoxazone (5mg/kg) and midazolam (5mg/kg) dissolved in a vehicle consisting of 5% ethanol, 5% DMSO, 35% polyethylene glycol 200, 40% phosphate buffered saline, and 15% water) as previously described (Finn et al., 2008). These substrates reflect the activities of Cyp1a, Cyp2c, Cyp2d, Cyp2e1, and Cyp3a/2c proteins respectively (Court et al., 1997; Masubuchi et al., 1997; Perloff et al., 2000; DeLozier et al., 2004; Lofgren et al., 2004).

In vivo pharmacokinetics: anti-cancer drugs

BCN and wild-type controls were administered the following drugs individually by oral gavage: cyclophosphamide (supplied as a 10mg/ml suspension) at 200mg/kg, paclitaxel (dissolved in a solution consisting of 5% vitamin E, 30% citric acid, 0.02% tyloxopol, 34.6% ethanol and 30% wv−1 d-α tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS) at 15mg/kg, anastrozole (dissolved in saline) at 0.3mg/kg, tamoxifen (dissolved in corn oil) at 15mg/kg and gefitinib (dissolved in an aqueous solution of 5% Tween 20) at 5mg/kg.

In all cases, whole blood (10 μl) was taken from the tail vein at intervals after drug administration (10, 20, 40, 60, 120, 240, 360 and 480 min), transferred into a tube containing heparin (10μl, 15 IU/ml). Details of extraction and analysis are in Supplemental Material.

Analysis of in vivo Pharmacokinetic data

Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using the WinNonLin software, v4.1. A non-compartmental model was used to calculate area under the curve (AUClast and AUCinfin), terminal half-life (t1/2), maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), and clearance (Cl). Data were then used to calculate p values using an unpaired t-test.

Immunoblotting

Microsomal fractions of liver and other mouse tissues were prepared by a modified method of Meehan et al., (Meehan et al., 1988) using sonication instead of mechanical homogenisation (Pritchard et al., 1998), and immunoblotted for cytochrome P450 expression as previously described (Finn et al., 2008), using polyclonal antisera raised against rat CYP1A1, CYP2B1, CYP2C6 and CYP3A1 (Forrester et al., 1992), or human full-length CYP2D6 and CYP2E1 (Pritchard et al., 1997; Pritchard et al., 1998). Immunoreactive proteins were detected using polyclonal goat anti-rabbit or anti-sheep horseradish peroxidase immunoglobulins as secondary antibodies (Dako, Ely, UK) and visualized using Immobilon chemiluminescent horseradish peroxidase substrate (Millipore, Watford, UK). The relative expression of immunoreactive proteins was quantified on a Fujifilm LAS-3000 imager, using Fujifilm Science Lab software (Multigauge v2.2, Fujifilm UK). Chemiluminescence from the blot is captured by the LAS-3000 and displayed digitally; by using the tools within the software, blots were enlarged, bands of interest selected and the absorbance quantified. Data output was expressed as (absorbance – back-ground absorbance)/mm2 and fold change with respect to WT calculated.

Drug cocktail microsomal incubations

Assays to determine steady-state activities were performed in triplicate with WT and BCN liver microsomes under conditions of linearity for time and protein (data not shown) using a 50 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 30 mM MgCl2 buffer containing the following concentrations of substrates/microsomes: cyclophosphamide 1 mM/25 μg microsomes, 10 min incubation; paclitaxel 50 μM/50 μg microsomes, 60 min incubation; gefitinib 75 μM/25 μg microsomes, 30 min incubation; anastrozole 0.5 μM/25 μg microsomes, 18 min incubation; and tamoxifen 50 μM/25 μg microsomes, 45 min incubation. Microsome/substrate mixes were pre-warmed to 37°C before initiation of reaction by addition of NADPH to 1 mM and reactions allowed to proceed for the indicated time period. The final volume of incubations was 100 μl. Assays were stopped by the addition of ice-cold methanol and metabolites were detected by LC MS/MS (see Supplemental Material). Gefitinib, tamoxifen and anastrozole activities were determined using microsomes prepared from female mice. Paclitaxel and cyclophosphamide activities were determined using microsomes prepared from male mice.

In vitro kinetic determinations for cocktail drugs using WT and BCN hepatic microsomes

Hepatic microsomal fractions from 3 individual mice were pooled and assays carried out in triplicate as previously described (Finn et al., 2008) under conditions of linearity for both time and protein concentration. Briefly, assays were performed the following concentrations of substrates: chlorzoxazone, 10–1000 μM; phenacetin, 1.7–150 μM; midazolam, 0.9–75 μM; metoprolol, 10–1000 μM; tolbutamide, 10–1000 μM (12 concentration points/determination). Metabolites were detected by LC-MS/MS as described in Finn et al., (Finn et al., 2008). The data generated were analysed by nonlinear regression using the Michaelis-Menten equation (chlorzoxazone, phenacetin, midazolam, and metoprolol), or the Hill equation (tolbutamide) (Grafit v 5; Erithacus Software Ltd; Horley; UK).

Results

Hepatic P450 expression in BCN mice

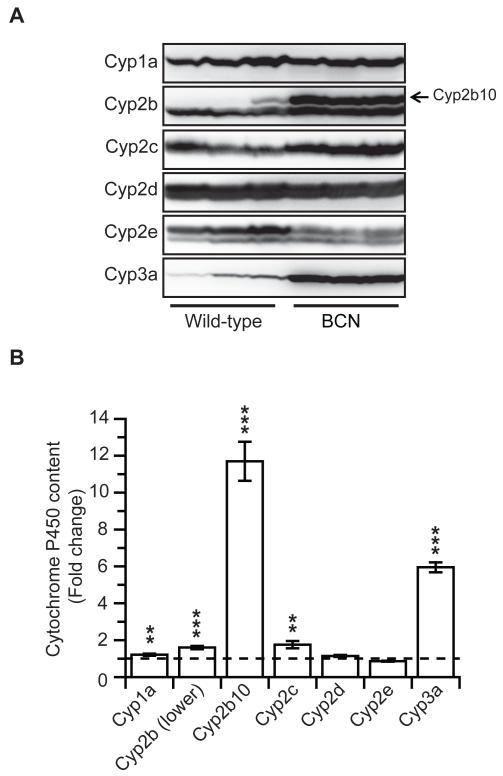

Immunoblot analysis for hepatic cytochrome P450 isozyme expression in wild-type and BCN mice (Figure 1) was carried out on hepatic microsomal samples derived from the mice used for the drug cocktail dosing experiment, where tissue was harvested at the end of the pharmacokinetic study (8h after the drug dosing). We have previously reported a significant 2-fold increase in total cytochrome hepatic P450 content in BCN samples relative to wild-type levels, from 0.4 ± 0.07 to 0.9 ± 0.4nmol P450/mg microsomal protein (McLaughlin et al., 2010). Also consistent with our published results, there was a significant increase in the expression of cytochrome Cyp2b10 (12-fold) and Cyp3a (6-fold) in BCN liver microsomes, compared to WT (Figure 1A & B). Levels of a further Cyp2b protein, and Cyp2c isoforms, were also slightly increased. These increases in P450 expression would be consistent with an activation of the transcription factors CAR and PXR; however this remains to be demonstrated. Similar trends in P450 expression were also observed in the liver-specific Cyb5 deleted HBN mice (Finn et al., 2008), although the effects were not as marked. The changes in P450 expression need to be taken into account when considering changes in in vivo pharmacokinetics as they could obscure any reduction in P450 activity as a consequence of Cyb5 deletion.

Figure 1. Hepatic cytochrome P450 isozyme levels in livers of wild-type and BCN mice.

A. Livers from wild-type and BCN mice used in the drug substrate pharmacokinetic analysis were harvested and microsomal fractions isolated (n =3). Western blotting (20 μg protein per lane) for the major P450s involved in the drug substrate metabolism (Cyp1a; Cyp2c, Cyp2d, Cyp2e and Cyp3a) was carried out as described in Experimental Procedures. Arrow indicates Cyp2b10 protein. B. Densitometric analysis of the Western blots shown in panel A. Data represents mean ± SD, * = p ≤ 0.05, ** = p ≤ 0.01, *** = p ≤ 0.001, relative to wild-type levels.

In vivo pharmacokinetics of a drug cocktail in wild-type and BCN mice

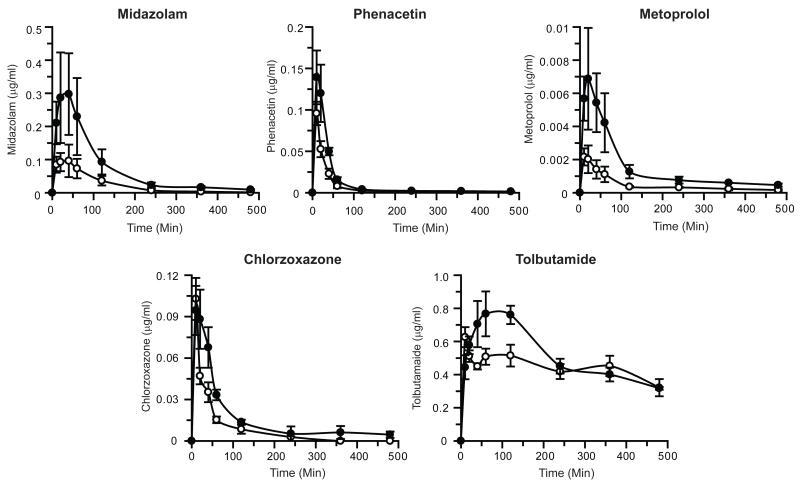

Pharmacokinetic profiles for WT and BCN mice using the five drug substrates administered as a cocktail are shown in Figure 2 and Table 1 with fold changes in pharmacokinetic parameters shown in Supplementary Figure 1. The pharmacokinetic data are also shown plotted as log concentration vs. time in Supplementary Figure 2. The data for metoprolol from this experiment was previously published in McLaughlin et al., (McLaughlin et al., 2010). For each drug, the global deletion of Cyb5 had a significant impact on drug disposition; however the magnitude of this change was substrate dependent. Midazolam (a Cyp3a and Cyp2c substrate) pharmacokinetics showed an increased AUC and Cmax along with a concomitant decrease in clearance (3.2-, 2.7- and 0.3-fold, respectively). As previously reported (McLaughlin et al., 2010), the pharmacokinetics for metoprolol (a Cyp 2d substrate) were also similarly affected by the absence of Cyb5, AUC, Cmax and clearance being altered by 3.4-, 4- and 0.3-fold, respectively; half-life was also significantly increased in the case of metoprolol (2.4-fold). Cyb5 deletion caused the AUC of chlorzoxazone (a Cyp2e1 substrate) to increase 2.1-fold and along with a 55% reduction in drug clearance, while in the case of phenacetin (a Cyp1a2 substrate) AUC was increased 1.8-fold, and clearance and half-life were both reduced to 55-65% of wild-type rates. Tolbutamide disposition (catalysed predominantly by Cyp2c P450s) was least affected by Cyb5 deletion with no significant change in Cmax or AUClast. Due to the ratio of AUClast/AUCinfin for tolbutamide being less than 0.8 (i.e. greater than 20% of the AUCinfin is extrapolated) (Gabrielsson and Weiner, 2007), the pharmacokinetic parameters calculated based on extrapolation of the terminal phase are likely to be error prone; therefore the data generated for AUCinfin; clearance or terminal half-life has not been included (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 2. Pharmacokinetic profiles of drug substrates in wild-type and BCN mice.

A P450 drug cocktail containing chlorzoxazone, metoprolol, midazolam, phenacetin and tolbutamide was administered to male mice, and pharmacokinetic profiles determined, as detailed in Experimental Procedures. Data represents mean ± SEM of drug concentrations in blood at the individual time points shown, n=5. Open circles – Wild-type mice; black circles - BCN mice. Data for metoprolol was previously reported (McLaughlin et al., 2010).

Table 1.

Comparison of pharmacokinetic parameters using a probe drug cocktail in wild-type and BCN mice

| Drug | PK parameters | Units | Wild-type | BCN | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midazolam | AUClast | (min*μg/ml) | 10.9 ± 3.4 | 35.3 ± 14.4 | n.s. |

| AUCinfin | (min*μg/ml) | 11.1 ± 7.5 | 36.0 ± 28.7 | n.s. | |

| Cmax | (μg/ml) | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.3 ± 0.13 | n.s. | |

| Clearance | (ml/min/kg) | 281.3 ± 46.7 | 96.0 ± 23.4 | * | |

| Terminal half-life | (min) | 78.2 ± 5.4 | 91.0 ± 8.1 | n.s. | |

|

| |||||

| Phenacetin | AUClast | (min*μg/ml) | 3.3 ± 0.58 | 5.8 ± 0.9 | * |

| AUCinfin | (min*μg/ml) | 3.4 ± 1.2 | 6.1 ± 1.7 | ns | |

| Cmax | (μg/ml) | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | n.s. | |

| Clearance | (ml/min/kg) | 1333 ±136 | 867 ± 102 | * | |

| Terminal half-life | (min) | 307 ± 44.5 | 171 ± 23.7 | * | |

|

| |||||

| Metoprolol b | AUClast | (min*μg/ml) | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 0.76 ± 0.24 | * |

| AUCinfin | (min*μg/ml) | 0.26 ± 0.09 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | * | |

| Cmax | (ng/ml) | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 8.0 ± 3.0 | * | |

| Clearance | (L/min/kg) | 8.4 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | ** | |

| Terminal half-life | (min) | 146.2 ± 29.8 | 350.2 ± 66.1 | * | |

|

| |||||

| Chlorzoxazone | AUClast | (min*μg/ml) | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 7.3 ± 0.7 | ** |

| AUCinfin | (min*μg/ml) | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 8.2 ± 1.7 | ** | |

| Cmax | (μg/ml) | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.02 | n.s. | |

| Clearance | (ml/min/kg) | 1387 ± 124.1 | 627 ± 64.9 | ** | |

| Terminal half-life | (min) | 44.4 ± 8.9 | 92.3 ± 33.9 | n.s. | |

|

| |||||

| Tolbutamide | AUClast | (min*μg/ml) | 213 ± 18.3 | 247 ± 16.5 | n.s. |

| Cmax | (μg/ml) | 0.63 ± 0.06 | 0.88 ± 0.11 | n.s. | |

p values relate to comparison between BCN and wild-type groups

p ≤ 0.05

p ≤ 0.01; n.s.: not significant

the data for metoprolol has previously been published (McLaughlin et al., 2010).

In vivo pharmacokinetics of anti-cancer drugs in wild-type and BCN mice

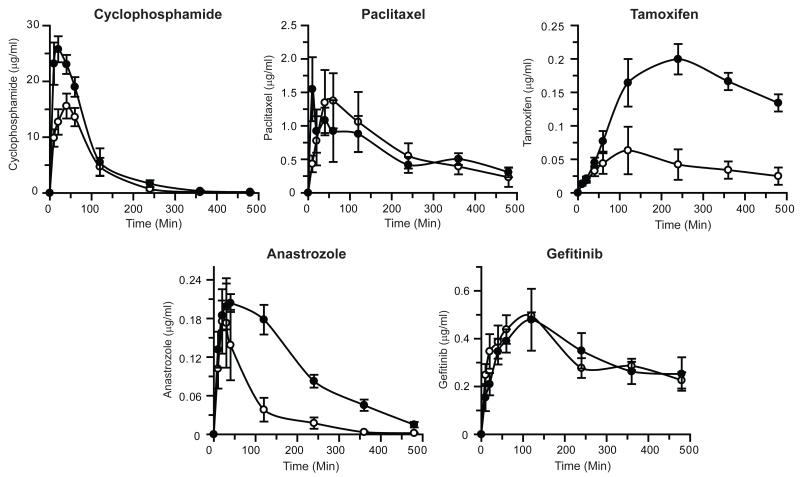

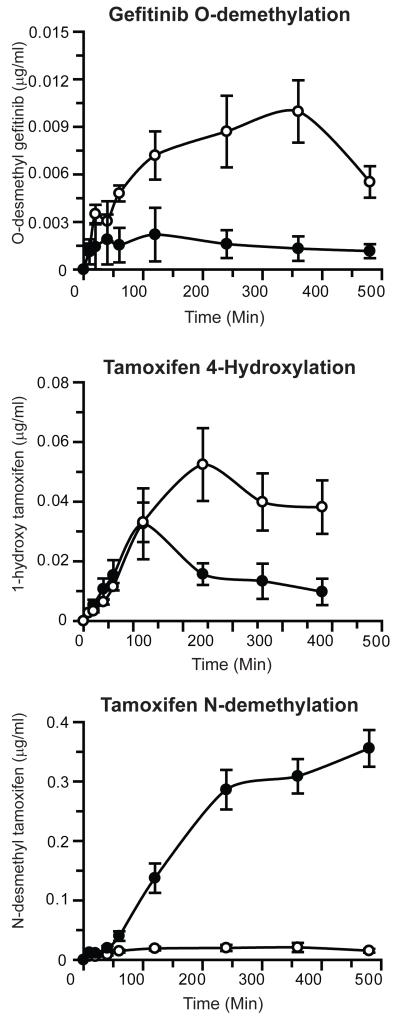

The effect of complete deletion of microsomal Cyb5 on the in vivo pharmacokinetics of cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel, tamoxifen, anastrozole and gefitinib following oral administration is shown in Figure 3, Supplementary Figure 3 and Table 2; the pharmacokinetic data are also shown plotted as log concentration vs. time in Supplementary Figure 4. Significant changes in the pharmacokinetic parameters for cyclophosphamide, tamoxifen and anastrozole were observed. Tamoxifen disposition was the most profoundly affected by Cyb5 deletion with Cmax and AUClast increased 4.7- and 3.3-fold respectively. AUClast/AUCinfin ratio for tamoxifen was 0.65 (WT) and 0.47 (BCN) therefore predicted pharmacokinetic parameters are not reported (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 3). For the major metabolites of tamoxifen, the 4-hydroxylated form was found at lower levels in BCN mice, whereas N-desmethyl tamoxifen levels were markedly higher (Figure 4). Furthermore, the half-lives of both cyclophosphamide and anastrozole were significantly increased in the BCN animals. The pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel and gefitinib were essentially unaffected by Cyb5 deletion. Similarly to tamoxifen; the AUClast/AUCinfin ratio for gefininib was 0.61 (WT) and 0.52 (BCN) therefore only AUClast and Cmax are reported (Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 3). Interestingly however, the level of the O-desmethyl gefitinib metabolite was significantly lower in mice lacking Cyb5 (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Pharmacokinetics of orally administered anti-cancer drugs in wild-type and BCN mice.

Anti-cancer drugs - cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel, tamoxifen, anastrozole and gefitinib –were administered, and pharmacokinetic profiles determined, as detailed in Experimental Procedures. Data represents the mean ± S.E.M. of drug concentrations in blood at the individual time points, n=5. Open circles - wild-type; black circles - BCN mice.

Table 2.

Comparison of pharmacokinetic parameters for anti-cancer drugs in wild-type and BCN mice

| Drugs | Parameter | Units | Wild-type | BCN | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide | AUClast | (min*μg/ml) | 1659 ± 287 | 2589 ± 367 | n.s. |

| AUCinfin | (min*μg/ml) | 1678 ± 641 | 2605 ± 821 | n.s. | |

| Cmax | (μg/ml) | 17.0 ± 1.6 | 26.4 ± 2.7 | * | |

| Clearance | (ml/min/kg) | 135 ± 24.5 | 82.5 ± 9.9 | n.s. | |

| Terminal half-life | (min) | 42.5 ± 5.2 | 60.1 ± 2.5 | * | |

|

| |||||

| Paclitaxel | AUClast | (min*μg/ml) | 318 ± 67.4 | 292 ± 67.4 | n.s. |

| AUCinfin | (min*μg/ml) | 381 ± 213 | 349 ± 168 | n.s. | |

| Cmax | (μg/ml) | 1.9 ± 0.40 | 2.2 ± 0.54 | n.s. | |

| Clearance | (ml/min/kg) | 51.2 ± 13.1 | 58.7 ± 20.1 | n.s. | |

| Terminal half-life | (min) | 148± 37.1 | 149 ± 24.9 | n.s. | |

|

| |||||

| Tamoxifen | AUClast | (min*μg/ml) | 16.4 ± 6.2 | 77.2 ±16.5 | *** |

| Cmax | (μg/ml) | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.2 ± 0.04 | *** | |

|

| |||||

| Anastrozole | AUClast | (min*μg/ml) | 22.4 ± 14.5 | 48.1 ± 10.0 | * |

| AUCinfin | (min*μg/ml) | 22.6 ± 14.5 | 50.4 ± 11.1 | * | |

| Cmax | (μg/ml) | 0.19 ± 0.13 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | n.s. | |

| Clearance | (ml/min/kg) | 29.3 ± 36.6 | 6.2 ± 1.4 | * | |

| Terminal half-life | (min) | 62.3 ± 6.7 | 101 ± 18.1 | ** | |

|

| |||||

| Gefitinib | AUClast | (min*μg/ml) | 162 ± 26.9 | 145 ± 62.1 | n.s. |

| Cmax | (μg/ml) | 0.5 ± 0.04 | 0.5 ± 0.20 | n.s. | |

p values relate to comparison between BCN and wild-type groups

p ≤ 0.05

p ≤ 0.01

p ≤0.001; n.s.: not significant

Figure 4. Production of gefitinib and tamoxifen metabolites in wild-type and BCN mice.

Anti-cancer drugs – tamoxifen and gefitinib were administered, and pharmacokinetic profiles of metabolites determined, as detailed in Experimental Procedures. Data represents the mean ± S.E.M. of metabolite concentrations in blood at the individual time points, n=5. Open circles - wild-type; black circles - BCN mice.

In vitro kinetic determinations for cocktail drugs in hepatic microsomes from wild-type and BCN microsomes

The apparent kinetic parameters for the cocktail drugs were determined in WT and BCN hepatic microsomes and the data are shown in Table 3. The Michaelis Menten equation was used to fit all data with the exception of tolbutamide hydroxylation, which was analysed using the Hill equation. Without exception, the Vmax for every reaction was markedly reduced in the BCN samples, ranging from 33% (metoprolol O-demethylation) to 99% (midazolam 1′-hydroxylation). Deletion of Cyb5 had minimal effect on the Km for chlorzoxazone, phenacetin, metoprolol and midazolam, while in the case of tolbutamide, the Km was 73% lower (977 ± 475 μM vs.3650 ± 636 μM). Hill coefficients of 0.88 and 0.72 for WT and HBN respectively, were indicative of tolbutamide binding in a negatively cooperative manner; a phenomenon we have previously reported for HBN samples (Finn et al., 2008).

Table 3.

In vitro kinetics of probe drugs by hepatic microsomes from wild-type and BCN mice

| WT | BCN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Km | Vmax | Km | Vmax | |

| Compound | (μM) | (pmol/min/mg) | (μM) | (pmol/min/mg) |

| Chlorzoxazone (6-hydroxylation) | 61.4 ± 7.6 | 527 ± 24 | 53.0 ± 5.6 | 90.9 ± 9.9 |

| Midazolam (1′-hydroxylation) | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 623 ± 22 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 7.3±0.3 |

| Midazolam (4-hydroxylation) | 21.8 ± 1.0 | 324 ± 6 | 18.4 ± 0.8 | 162 ± 3 |

| Phenacetin (O-demethylation) | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 540 ± 11 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 397 ± 17 |

| Metoprolol (α-hydroxylation) | 66.5 ± 8.8 | 1004 ± 43 | 73.4 ± 12.4 | 310 ± 11 |

| Metoprolol (O-demethylation) | 59.0 ± 7.7 | 862 ± 36 | 78.5 ± 20.3 | 580 ± 52 |

| Tolbutamide (hydroxylation) | 3650 ± 636 | 60 ± 6 | 977 ± 475 | 17.6 ± 4.3 |

Hepatic microsomal samples from 3 individual mice were pooled and assays were performed in triplicate for each concentration of substrate as described in the Materials and Methods section. Standard deviations given are from the fit of the curve as calculated using the Michaelis Menten equation (GraFit version 5 (Erithacus Software, Horley, UK)). For tolbutamide, the Hill equation was used to fit the data, giving Hill Coefficients of 0.88 and 0.72 for wild-type and BCN, respectively.

Hepatic in vitro activities towards the panel of anti-cancer drugs in wild-type and Cyb5 null mice

In vitro incubations were performed using liver microsomes devoid of Cyb5 from BCN mice and activities compared to WT. Data are presented in Table 4. The removal of Cyb5 from the P450 mono-oxygenase system caused a marked reduction in P450 activity ranging from 75% in the case of gefitinib O-demethylation to 50% for tamoxifen 4-hydroxylation, which was statistically significant for all drugs except paclitaxel (p=0.054).

Table 4.

In vitro activities of wild type and cytochrome b5 null hepatic microsomes towards a panel of anti-cancer drugs

| Compound | WT (pmol/min/mg) |

Cyb5 deletion (pmol/min/mg) |

p-valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide 4-hydroxylation | 8940 ± 1960 | 4180 ± 830 | * |

| Paclitaxel 6-hydroxylation | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | n.s. |

| Tamoxifen 4-hydroxylation | 154 ± 43 | 76 ± 15 | * |

| Anastrozole metabolism | 29 ± 3%a | 10 ± 9%a | * |

| Gefitinib O-demethylation | 27± 12 | 6.6 ± 1.9 | * |

Assays were performed in triplicate for three mice per genotype using hepatic microsomes from HBN mice as described in Materials and methods.

Percentage of anastrozole metabolised in an 18 min incubation.

p ≤ 0.05; n.s.: not significant

Discussion

Cytochrome b5 is expressed in most tissues, with the highest levels found in liver, lung and kidney (Wu et al., 2009), and has been shown to play an active role in in vitro both hepatic and extra-hepatic drug metabolism (Dekant et al., 1995; Ding and Kaminsky, 2003; Finn et al., 2008; McLaughlin et al., 2010). In this study we have evaluated the in vivo pharmacokinetics of a range of drug substrates and anti-cancer drugs in a model where Cyb5 is deleted in all tissues to ascertain the extent to which Cyb5 can influence their overall disposition. We have also assessed the effect of Cyb5 deletion on the in vitro metabolism of these compounds, allowing comparison with the in vivo data.

As described previously, deletion of Cyb5 increased the hepatic expression of several P450s, particularly Cyp2b10 and Cyp3a, and is more marked in BCN relative to that observed in the hepatic deletion model (Finn et al., 2008; McLaughlin et al., 2010). Furthermore, the levels of P450 induction were not increased by dosing with a drug cocktail containing midazolam, metoprolol, chlorzoxazone, phenacetin and tolbutamide (Figure 1). The mechanism which underlies the P450 induction however, remains unclear. Induction of hepatic cytochrome P450s has also been observed in the hepatic P450 reductase null (HRN) model (Henderson et al., 2003); this was shown to be due to activation of the transcription factor CAR as a consequence of increased unsaturated fatty acids in the liver due to hepatic steatosis (Finn et al., 2009). Although livers from BCN mice are not steatotic (McLaughlin et al., 2010), significant increases in hepatic and plasma unsaturated fatty acids have been reported in BCN mice (Finn et al., 2011). It is feasible that a reduction in metabolism due to Cyb5 deletion is compensated for by increased expression of the P450(s) responsible for drug disposition. It is striking however, that although there is a 6-fold increase in the hepatic expression of Cyp3a proteins, the in vitro and in vivo metabolism of Cyp3a substrates midazolam, cyclophosphamide, tamoxifen and anastrozole is still significantly reduced. This would indicate that the true extent of the effect of Cyb5 deletion is even greater than that measured.

In addition to its role in drug metabolism Cyb5 can act as electron donor to the stearate desaturase pathway. It is therefore feasible that the effects on drug metabolism seen here are due to changes in the fatty acid composition of the endoplasmic reticulum. However, it is very unlikely that such an effect would cause the marked changes observed, and furthermore the re-introduction of recombinant Cyb5 into microsomal membranes derived from hepatic Cyb5 null mice reverses the loss of P450 activity (Finn et al., 2008; McLaughlin et al., 2010). It is interesting to note that most in vitro studies have suggested that human CYP1A2 and CYP2D6 do not exhibit a Cyb5 dependency (Dehal and Kupfer, 1997; Yamazaki et al., 2002). The fact that the homologous proteins in the mouse are clearly affected suggests that there may be an important species difference in Cyb5 effects with these classes of enzyme. In vivo studies to establish whether this is the case are currently in progress.

To date, little consideration of Cyb5 is taken into account in the prediction of in vivo pharmacokinetics from in vitro experiments; however studies are now reporting that these extrapolations are more accurately estimated when Cyb5 is taken into account (Emoto and Iwasaki, 2007; Crewe et al., 2011). Indeed, it is clear from our BCN pharmacokinetic data that Cyb5 plays a pivotal role in the in vivo disposition of 70% of the drugs we have studied (midazolam, metoprolol, chlorzoxazone, phenacetin, tamoxifen, anastrozole and cyclophosphamide). It is interesting to note however, that the in vitro data showed a significant Cyb5 dependence for all ten substrates examined. Deletion of Cyb5 caused a 62%, 70% and 75% reduction in paclitaxel, tolbutamide and gefitinib metabolism in vitro respectively; however no significant effect of global Cyb5 deletion on the in vivo pharmacokinetics of these drugs was observed. In the case of paclitaxel, the in vivo disposition in mouse is P450-dependent (HRN model, unpublished data). The 6-hydroxy metabolite of paclitaxel (Table 4), whilst being the major human pathway of disposition (Sonnichsen et al., 1995), was shown by Hendrikx et al., (Hendrikx et al., 2013) to be formed at very low levels in wild-type mouse samples and thus may not represent the primary P450-mediated metabolite formed in the mouse. Nonetheless, our in vivo data clearly indicate that Cyb5 does not affect the major pathways of P450-mediated paclitaxel disposition in the mouse.

In mouse, hydroxylation of tolbutamide is a major route of both in vitro and in vivo disposition (DeLozier et al., 2004; Finn et al., 2008; Scheer et al., 2012a); furthermore in reconstitution experiments using human enzymes, Cyb5 was found to enhance the CYP2C9 mediated hydroxylation of tolbutamide (Yamazaki et al., 1997; Crewe et al., 2011). Data from the HBN model, however, clearly indicate that Cyb5 does not significantly affect the in vivo disposition of tolbutamide (Finn et al., 2008). Tolbutamide pharmacokinetics in BCN mice (Figure 1 and 2, Table 2) are consistent with that observed in the HBN model. Gefitinib is metabolised in vitro by CYP3A4/5 in humans to a variety of metabolites, but the major circulating plasma metabolite (O-desmethyl gefitinib) formed by CYP2D6 is only a minor microsomal product. In BCN animals, both in vivo and in vitro, production of O-desmethyl gefitinib was significantly reduced (Table 4 and Figure 4). However, the similarity of gefitinib pharmacokinetics in BCN and WT mice would imply that this is not the major route of gefitinib disposition in mice. Taken together, these data indicate that when considering the effect of Cyb5 on P450 activity, direct extrapolation of the in vitro data to the in vivo situation cannot be automatically assumed.

It is worthy of note that in our previous studies there were no significant differences in the disposition of either metoprolol or chlorzoxazone in the HBN mouse indicating that hepatic Cyb5 is not involved in their metabolism (Finn et al., 2008). However, in the BCN mice significant differences were observed with these drugs, indicative of Cyb5 involvement in extra-hepatic metabolism (this study; also (McLaughlin et al., 2010)). Interestingly, when the pharmacokinetics of the anti-cancer drugs used in this study were compared between HBN and BCN mice (data not shown), no significant differences were observed between the two models, indicating that extra-hepatic Cyb5 does not play a role in their disposition. These observations indicate that the HBN and BCN models could be used in conjunction as a powerful tool to dissect the role of Cyb5 in hepatic and extra-hepatic P450-mediated drug metabolism.

With the exception of phenacetin, all drugs used in this study are commonly-prescribed medications in current therapeutic use, highlighting the clinical relevance of Cyb5 on P450-mediated drug metabolism and potential effects on efficacy and toxicity. Tamoxifen, a pro-drug whose anti-cancer activity is dependent on the P450-mediated generation of the metabolites 4-hydroxytamoxifen and N-desmethyl tamoxifen (which is subsequently metabolised to endoxifen), is not subject to routine therapeutic monitoring and is dosed according to a standard protocol, resulting in wide range of concentrations of parent drug and metabolites in patients (Gjerde et al., 2012). Critically, deletion of Cyb5 caused a 5-fold increase in systemic tamoxifen exposure, resulting in a significant increase in circulating levels of the active metabolite, N-desmethyl tamoxifen (Figure 4), demonstrating that Cyb5 levels could be a major determinant of tamoxifen metabolism and thus its therapeutic effects. Furthermore most anti-cancer drugs have a narrow therapeutic window; therefore levels of Cyb5 play an important role in the efficacy and toxicity for those drugs metabolised by the P450 system.

Both genetic and environmental factors (Kawata et al., 1982; Kariya et al., 1984; Dharia et al., 2005; Kurian et al., 2007; Idkowiak et al., 2012) may contribute to the expression levels of Cyb5 and thus contribute to variability in drug efficacy and toxicity. Cyb5 expression in human liver has previously been shown to vary by 2.5-5-fold (Forrester et al., 1992; Sacco and Trepanier, 2012); in the present study, using an independent panel of 16 human livers, we have detected a 5-fold variation in Cyb5 protein levels (Supplemental Figure 5). Additionally, mutations in the Cyb5 reductase gene, which supplies electrons to Cyb5, could potentially affect catalytic efficiency (Vieira et al., 1995; Kugler et al., 2001). Cyb5 has been shown to interact with CYP2B6 and CYP2C9 in a polymorphism-specific manner, adding further complexity to P450-Cyb5 interactions (Kaspera et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2012). Collectively, this suggests that both genetic and environmental changes in Cyb5 levels, and/or catalytic efficiency, could be important contributing factors to inter-individual heterogeneity in drug disposition and efficacy, and which are currently overlooked. The availability of mice humanised for the major hepatic P450s, i.e. CYP3A4, CYP2D6 and CYP2C9 (Scheer et al., 2008; Hasegawa et al., 2011; Scheer et al., 2012a; Scheer et al., 2012b) should allow extension of this work, yielding important insights into the interaction of Cyb5 with human P450 enzymes in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Catherine Meakin and Susanne van Schelven are thanked for excellent technical assistance.

This work was funded by a Cancer Research UK Programme Grant [C4639/A12330].

Abbreviations

- AUCinfin

area under the curve extrapolated to infinity

- AUClast

area under the curve until the last time point

- BCN

Cytochrome b5 Complete Null

- Cl

clearance

- Cmax

maximum plasma concentration

- Cyb5

cytochrome b5

- HBN

Hepatic b5 Null

- HRN

Hepatic cytochrome P450 Reductase Null

- WT

wild-type

- t1/2

terminal half-life

- TPGS

d-α tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate

Contributor Information

Colin J. Henderson, Division of Cancer Research, Medical Research Institute, Level 9, Jacqui Wood Cancer Centre, University of Dundee, James Arrott Drive, Ninewells Hospital & Medical School, Dundee DD1 9SY, UK

Lesley A. McLaughlin, Division of Cancer Research, Medical Research Institute, Level 9, Jacqui Wood Cancer Centre, University of Dundee, James Arrott Drive, Ninewells Hospital & Medical School, Dundee DD1 9SY, UK

Robert D. Finn, Department of Applied Sciences, Faculty of Health & Life Sciences, Ellison Building, Northumbria University, Newcastle, NE1 8ST

Sebastien Ronseaux, Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research, Inc., 250 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA.

Yury Kapelyukh, Division of Cancer Research, Medical Research Institute, Level 9, Jacqui Wood Cancer Centre, University of Dundee, James Arrott Drive, Ninewells Hospital & Medical School, Dundee DD1 9SY, UK.

C. Roland Wolf, Division of Cancer Research, Medical Research Institute, Level 9, Jacqui Wood Cancer Centre, University of Dundee, James Arrott Drive, Ninewells Hospital & Medical School, Dundee DD1 9SY, UK.

References

- Akhtar MK, Kelly SL, Kaderbhai MA. Cytochrome b(5) modulation of 17{alpha} hydroxylase and 17-20 lyase (CYP17) activities in steroidogenesis. J Endocrinol. 2005;187:267–274. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arinc E, Pasha RP, Adali O, Basaran N. Stimulatory effects of lung cytochrome b5 on benzphetamine N-demethylation in a reconstituted system containing lung cytochrome P450LgM2. The International journal of biochemistry. 1994;26:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court MH, Von Moltke LL, Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ. Biotransformation of chlorzoxazone by hepatic microsomes from humans and ten other mammalian species. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1997;18:213–226. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-081x(199704)18:3<213::aid-bdd15>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crewe HK, Barter ZE, Yeo KR, Rostami-Hodjegan A. Are there differences in the catalytic activity per unit enzyme of recombinantly expressed and human liver microsomal cytochrome P450 2C9? A systematic investigation into inter-system extrapolation factors. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2011;32:303–318. doi: 10.1002/bdd.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehal SS, Kupfer D. CYP2D6 catalyzes tamoxifen 4-hydroxylation in human liver. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3402–3406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekant W, Frischmann C, Speerschneider P. Sex, organ and species specific bioactivation of chloromethane by cytochrome P4502E1. Xenobiotica. 1995;25:1259–1265. doi: 10.3109/00498259509046681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLozier TC, Tsao CC, Coulter SJ, Foley J, Bradbury JA, Zeldin DC, Goldstein JA. CYP2C44, a new murine CYP2C that metabolizes arachidonic acid to unique stereospecific products. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:845–854. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.067819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dharia S, Slane A, Jian M, Conner M, Conley AJ, Brissie RM, Parker CR., Jr. Effects of aging on cytochrome b5 expression in the human adrenal gland. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4357–4361. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Kaminsky LS. Human extrahepatic cytochromes P450: function in xenobiotic metabolism and tissue-selective chemical toxicity in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2003;43:149–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.140251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emoto C, Iwasaki K. Approach to predict the contribution of cytochrome P450 enzymes to drug metabolism in the early drug-discovery stage: the effect of the expression of cytochrome b(5) with recombinant P450 enzymes. Xenobiotica. 2007;37:986–999. doi: 10.1080/00498250701620692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Henderson CJ, Scott CL, Wolf CR. Unsaturated fatty acid regulation of cytochrome P450 expression via a CAR-dependent pathway. Biochem J. 2009;417:43–54. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, McLaughlin LA, Hughes C, Song C, Henderson CJ, Roland Wolf C. Cytochrome b5 null mouse: a new model for studying inherited skin disorders and the role of unsaturated fatty acids in normal homeostasis. Transgenic Res. 2011;20:491–502. doi: 10.1007/s11248-010-9426-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, McLaughlin LA, Ronseaux S, Rosewell I, Houston JB, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR. Defining the in Vivo Role for Cytochrome b5 in Cytochrome P450 Function through the Conditional Hepatic Deletion of Microsomal Cytochrome b5. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31385–31393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803496200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester LM, Henderson CJ, Glancey MJ, Back DJ, Park BK, Ball SE, Kitteringham NR, McLaren AW, Miles JS, Skett P, et al. Relative expression of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes in human liver and association with the metabolism of drugs and xenobiotics. Biochem J. 1992;281(Pt 2):359–368. doi: 10.1042/bj2810359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielsson J, Weiner D. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Data Analysis: Concepts and Applications. Swedish Pharmaceutical Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gjerde J, Gandini S, Guerrieri-Gonzaga A, Haugan Moi LL, Aristarco V, Mellgren G, Decensi A, Lien EA. Tissue distribution of 4-hydroxy-N-desmethyltamoxifen and tamoxifen-N-oxide. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2012;134:693–700. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Chen CS, Wei Y, Fang C, Xie F, Kannan K, Yang W, Waxman DJ, Ding X. A mouse model with liver-specific deletion and global suppression of the NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase gene: characterization and utility for in vivo studies of cyclophosphamide disposition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321:9–17. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.118240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Kapelyukh Y, Tahara H, Seibler J, Rode A, Krueger S, Lee DN, Wolf CR, Scheer N. Quantitative prediction of human pregnane X receptor and cytochrome P450 3A4 mediated drug-drug interaction in a novel multiple humanized mouse line. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:518–528. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.071845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson CJ, Otto DM, Carrie D, Magnuson MA, McLaren AW, Rosewell I, Wolf CR. Inactivation of the hepatic cytochrome P450 system by conditional deletion of hepatic cytochrome P450 reductase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13480–13486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrikx JJ, Lagas JS, Rosing H, Schellens JH, Beijnen JH, Schinkel AH. P-glycoprotein and cytochrome P450 3A act together in restricting the oral bioavailability of paclitaxel. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2013;132:2439–2447. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idkowiak J, Randell T, Dhir V, Patel P, Shackleton CH, Taylor NF, Krone N, Arlt W. A Missense Mutation in the Human Cytochrome b5 Gene causes 46,XY Disorder of Sex Development due to True Isolated 17,20 Lyase Deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffcoat R, Brawn PR, Safford R, James AT. Properties of rat liver microsomal stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase. Biochem J. 1977;161:431–437. doi: 10.1042/bj1610431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kariya K, Lee E, Yamaoka M, Ishikawa H. Selective induction of cytochrome b5 and NADH cytochrome b5 reductase by propylthiouracil. Life Sci. 1984;35:2327–2334. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaspera R, Naraharisetti SB, Evangelista EA, Marciante KD, Psaty BM, Totah RA. Drug metabolism by CYP2C8.3 is determined by substrate dependent interactions with cytochrome P450 reductase and cytochrome b5. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawata S, Sugiyama T, Seki K, Tarui S, Okamoto M, Yamano T. Stimulatory effect of cytochrome b5 induced by p-nitroanisole and diisopropyl 1,3-dithiol-2-ylidenemalonate on rat liver microsomal drug hydroxylations. J Biochem. 1982;92:305–313. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kominami S, Ogawa N, Morimune R, De-Ying H, Takemori S. The role of cytochrome b5 in adrenal microsomal steroidogenesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;42:57–64. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugler W, Pekrun A, Laspe P, Erdlenbruch B, Lakomek M. Molecular basis of recessive congenital methemoglobinemia, types I and II: Exon skipping and three novel missense mutations in the NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase (diaphorase 1) gene. Hum Mutat. 2001;17:348. doi: 10.1002/humu.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian JR, Longlais BJ, Trepanier LA. Discovery and characterization of a cytochrome b5 variant in humans with impaired hydroxylamine reduction capacity. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:597–603. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328011aaff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb DC, Kaderbhai NN, Venkateswarlu K, Kelly DE, Kelly SL, Kaderbhai MA. Human sterol 14alpha-demethylase activity is enhanced by the membrane-bound state of cytochrome b(5) Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;395:78–84. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofgren S, Hagbjork AL, Ekman S, Fransson-Steen R, Terelius Y. Metabolism of human cytochrome P450 marker substrates in mouse: a strain and gender comparison. Xenobiotica. 2004;34:811–834. doi: 10.1080/00498250412331285463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masubuchi Y, Iwasa T, Hosokawa S, Suzuki T, Horie T, Imaoka S, Funae Y, Narimatsu S. Selective deficiency of debrisoquine 4-hydroxylase activity in mouse liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:1435–1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin LA, Ronseaux S, Finn RD, Henderson CJ, Roland Wolf C. Deletion of microsomal cytochrome b5 profoundly affects hepatic and extrahepatic drug metabolism. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:269–278. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.064246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan RR, Forrester LM, Stevenson K, Hastie ND, Buchmann A, Kunz HW, Wolf CR. Regulation of phenobarbital-inducible cytochrome P-450s in rat and mouse liver following dexamethasone administration and hypophysectomy. Biochem J. 1988;254:789–797. doi: 10.1042/bj2540789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pass GJ, Carrie D, Boylan M, Lorimore S, Wright E, Houston B, Henderson CJ, Wolf CR. Role of hepatic cytochrome p450s in the pharmacokinetics and toxicity of cyclophosphamide: studies with the hepatic cytochrome p450 reductase null mouse. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4211–4217. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perloff MD, von Moltke LL, Court MH, Kotegawa T, Shader RI, Greenblatt DJ. Midazolam and triazolam biotransformation in mouse and human liver microsomes: relative contribution of CYP3A and CYP2C isoforms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:618–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter TD. The roles of cytochrome b5 in cytochrome P450 reactions. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2002;16:311–316. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard MP, Glancey MJ, Blake JA, Gilham DE, Burchell B, Wolf CR, Friedberg T. Functional co-expression of CYP2D6 and human NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase in Escherichia coli. Pharmacogenetics. 1998;8:33–42. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199802000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard MP, Ossetian R, Li DN, Henderson CJ, Burchell B, Wolf CR, Friedberg T. A general strategy for the expression of recombinant human cytochrome P450s in Escherichia coli using bacterial signal peptides: expression of CYP3A4, CYP2A6, and CYP2E1. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;345:342–354. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remacle J, Fowler S, Beaufay H, Amarcostesec A, Berthet J. Analytical study of microsomes and isolated subcellular membranes from rat liver. VI. Electron microscope examination of microsomes for cytochrome b5 by means of a ferritin-labeled antibody. J Cell Biol. 1976;71:551–564. doi: 10.1083/jcb.71.2.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco JC, Trepanier LA. Cytochrome b5 and NADH cytochrome b5 reductase: genotype-phenotype correlations for hydroxylamine reduction. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2012;20:26–37. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283343296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer N, Kapelyukh Y, Chatham L, Rode A, Buechel S, Wolf CR. Generation and characterization of novel cytochrome P450 Cyp2c gene cluster knockout and CYP2C9 humanized mouse lines. Mol Pharmacol. 2012a;82:1022–1029. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.080036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer N, Kapelyukh Y, McEwan J, Beuger V, Stanley LA, Rode A, Wolf CR. Modeling human cytochrome P450 2D6 metabolism and drug-drug interaction by a novel panel of knockout and humanized mouse lines. Mol Pharmacol. 2012b;81:63–72. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.075192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer N, Ross J, Rode A, Zevnik B, Niehaves S, Faust N, Wolf CR. A novel panel of mouse models to evaluate the role of human pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor in drug response. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3228–3239. doi: 10.1172/JCI35483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkman JB, Jansson I. The many roles of cytochrome b5. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;97:139–152. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnichsen DS, Liu Q, Schuetz EG, Schuetz JD, Pappo A, Relling MV. Variability in human cytochrome P450 paclitaxel metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:566–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbreit J. Methemoglobin--it’s not just blue: a concise review. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:134–144. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira LM, Kaplan JC, Kahn A, Leroux A. Four new mutations in the NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase gene from patients with recessive congenital methemoglobinemia type II. Blood. 1995;85:2254–2262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waskell L, Canova-Davis E, Philpot R, Parandoush Z, Chiang JY. Identification of the enzymes catalyzing metabolism of methoxyflurane. Drug Metab Dispos. 1986;14:643–648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Orozco C, Boyer J, Leglise M, Goodale J, Batalov S, Hodge CL, Haase J, Janes J, Huss JW, 3rd, Su AI. BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R130. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-11-r130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Ogburn ET, Guo Y, Desta Z. Effects of the CYP2B6*6 allele on catalytic properties and inhibition of CYP2B6 in vitro: implication for the mechanism of reduced efavirenz metabolism and other CYP2B6 substrates in vivo. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40:717–725. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.042416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaori S, Yamazaki H, Suzuki A, Yamada A, Tani H, Kamidate T, Fujita K, Kamataki T. Effects of cytochrome b(5) on drug oxidation activities of human cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3As: similarity of CYP3A5 with CYP3A4 but not CYP3A7. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;66:2333–2340. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H, Gillam EM, Dong MS, Johnson WW, Guengerich FP, Shimada T. Reconstitution of recombinant cytochrome P450 2C10(2C9) and comparison with cytochrome P450 3A4 and other forms: effects of cytochrome P450-P450 and cytochrome P450-b5 interactions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;342:329–337. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H, Johnson WW, Ueng YF, Shimada T, Guengerich FP. Lack of electron transfer from cytochrome b5 in stimulation of catalytic activities of cytochrome P450 3A4. Characterization of a reconstituted cytochrome P450 3A4/NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase system and studies with apo-cytochrome b5. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27438–27444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki H, Nakamura M, Komatsu T, Ohyama K, Hatanaka N, Asahi S, Shimada N, Guengerich FP, Shimada T, Nakajima M, Yokoi T. Roles of NADPH-P450 reductase and apo- and holo-cytochrome b5 on xenobiotic oxidations catalyzed by 12 recombinant human cytochrome P450s expressed in membranes of Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2002;24:329–337. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Hamdane D, Im SC, Waskell L. Cytochrome b5 inhibits electron transfer from NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase to ferric cytochrome P450 2B4. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5217–5225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709094200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Myshkin E, Waskell L. Role of cytochrome b5 in catalysis by cytochrome P450 2B4. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.