Abstract

Background and aims. Helicobacter pylori is a microaerophilic gram-negative spiral organism. It is recognized as the etiologic factor for peptic ulcers, gastric adenocarcinoma and gastric lymphoma. Recently, it has been isolated from dental plaque and the dorsum of the tongue. This study was designed to assess the association between H. pylori and oral lesions such as ulcerative/inflammatory lesions, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and primary lymphoma.

Materials and methods. A total of 228 biopsies diagnosed as oral ulcerative/inflammatory lesions, oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and oral primary lymphoma were selected from the archives of the Pathology Department. Thirty-two samples that were diagnosed as being without any pathological changes were selected as the control group. All the paraffin blocks were cut for hematoxylin and eosin staining to confirm the diagnoses and then the samples were prepared for immunohistochemistry staining. Data were collected and analyzed.

Results. Chi-squared test showed significant differences between the frequency of H. pylori positivity in normal tissue and the lesions were examined (P=0.000). In addition, there was a statistically significant difference between the lesions examined (P=0.042). Chi-squared test showed significant differences between H. pylori positivity and different tissue types except inside the muscle layer as follows: in epithelium and in lamina propria (P=0.000), inside the blood vessels (P=0.003), inside the salivary gland duct (P=0.036), and muscle layer (P=0.122).

Conclusion. There might be a relation between the presence of H. pylori and oral lesions. Therefore, early detection and eradication of H. pylori in high-risk patients are suggested.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, oral ulcer, oral squamous cell carcinoma, oral lymphoma

Introduction

The majority of head and neck cancer cases are related to tobacco use and heavy alcohol consumption.1 Other possible risk factors include viral infections,2 infection with Candida species and poor oral hygiene.3 A number of bacterial species are associated with different cancers.4 Increasing evidence shows the association of bacteria with some oral cancers.5,6 There is also a great diversity between different biological surfaces in the oral cavity for colonization of different bacterial species. For example, the salivary microbiota is mostly similar to that of the dorsal and lateral surfaces of the tongue but supragingival bacteria colonization is different from the microbiota on the oral soft tissue surfaces and in saliva.7

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a microaerophilic gram-negative spiral organism. In 1983, H. pylori was isolated for the first time by Marshall and Warren from human gastric biopsy specimens.8Different studies have revealed that H. pylori can be isolated from the oral cavity, dental plaque (supragingival and subgingival plaque), dorsum of the tongue and salivary secretions.9-12There are conflicting reports about the presence of H. pylori in the oral cavity and dental plaque. Wide variations in the prevalence of H. pylori in the oral cavity are partly due to employing different detection methods. For example, in a study by Butt et al, using urease test and cytology, H. pylori was detected in 100% and 88% of dental plaque samples, respectively.13In another study, H. pylori was detected in the saliva of 54.1% and in dental pockets in 48.3% of examined cases,11 and was considered a resident of the oral cavity. However, Chitsaziet al detected H. pylori in 34.1% of dental plaque samples.14

In addition, the presence of H. pylori was reported by Silva et al, using PCR, in 11.3% of supragingival plaque samples with or without periodontal diseases.15In a study, Mravak-Stipetićet al detected H. pylori in 13.04% of patients with different oral lesions.16 In another study on head and neck malignant and premalignant conditions, H. pylori was detected in 62.2% of cases.17H. pylori exists in high prevalence in the saliva and may be transmitted orally or via the fecal-oral route.18

The association of H. pylori with the pathogenesis of peptic and duodenal ulcers, gastric adenocarcinoma and low-grade B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma has also been proven.19,20

H. pylori might have a role in the pathogenesis of oral lesions, e.g. ulcers, carcinomas and lymphomas. To assess this association, this study was designed to detect H. pylori in oral lesions including ulcerative/inflammatory lesions, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and primary lymphoma.

Materials and Methods

A total of 228 biopsies diagnosed as ulcerative/inflammatory lesions, oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and oral primary lymphoma were selected from the archives of the Pathology Department. Thirty-two tissue samples taken from different areas of the oral cavity for other purposes, such as crown lengthening, and also samples with pathology reports stating “without significant pathological changes” were selected as the control group.

All the paraffin blocks were cut for H&E staining to confirm the diagnoses and then the samples were prepared for the immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining.

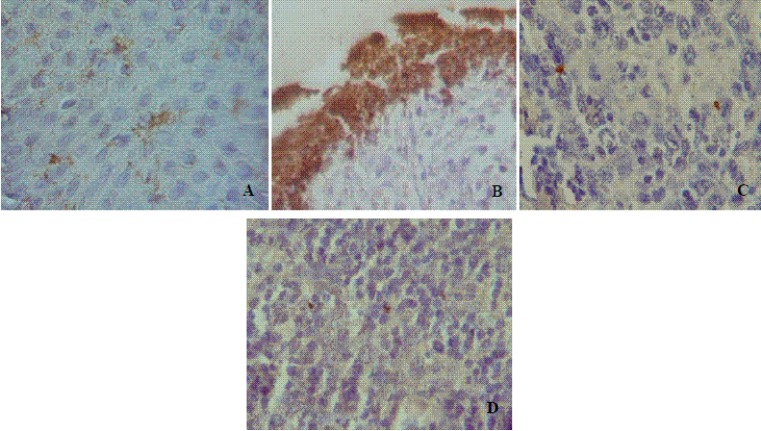

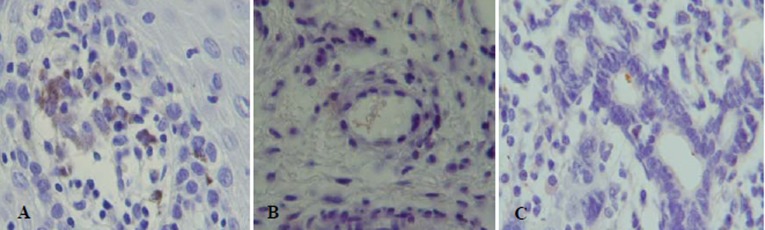

Briefly, 4-μm-thick sections of paraffin-embedded formalin-fixed specimens were cut. The slides were deparaffinized, rehydrated and pre-treated with trypsin for 40 minutes at 37°C according to manufacturer’s instructions (Novocastra, UK). The endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked, followed by incubation with lyophilized rabbit polyclonal antibody (Novocastra) at a dilution of 1:20 for 1 hour. DAB was used to visualize the complex. Then, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted. H. pylori-positive and -negative human gastric samples were used as positive and negative controls, respectively(Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Sections of oral mucosa immunostained with H. pylori antibody. A) In the normal epithelium. B) Over the ulcer. C) In squamous cell carcinoma section. D) Primary lymphoma (×1000).

Figure 2.

The coccoid and irregular forms of H. pylori. A) Within the lamina propria. Note also H. pylori in macro-phages. B) Inside the blood vessel. C) Inside the salivary duct (×1000).

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 11.0.1 using chi-squared test. Statistical significance between the groups was set at P<0.05.

Results

In this study, there were 141 males (54.2%) and 119 females (45.8%). In general, the ages of the patients ranged from 7 to 80 years, with a mean age of 43.18 years. Demographic data of the samples are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of samples .

| Study group | No. of cases | Male | Female | Median age (years) | Range of age |

| Normal tissue | 32(12.3%) | 9 | 23 | 39.6 | 7-78 |

| Ulcerative/Inflammatory lesion | 117(45%) | 75 | 42 | 38.9 | 7-80 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 83(31.9%) | 39 | 44 | 50.9 | 31-75 |

| Lymphoma | 28(10.7%) | 18 | 10 | 42.3 | 34-68 |

| Total | 260 | 141 | 119 | 43.18 | 7-80 |

Table 2 shows the presence of H. pylori in different areas of the oral cavity. According to Table 2, H. pylori positivity was mostly found in the tonsils and tongue, with 43 (16.5%) and 42 (16.1%) cases, respectively. H. pylori negativity was mostly found in the tongue, with 17 (6.5%) cases, followed by the buccal mucosa and oropharynx, with nine (3.4%) cases each. According to Table 2, most of the tonsil and tongue H. pylori positivity was found in ulcerative/inflammatory lesions, with 37 cases (14.2%) and 26 cases (10%), respectively. On the other hand, most of the H. pylori-positive SCC samples were found in the soft palate and oropharynx, with 14 cases (5.3%) each. The buccal mucosa was the most common site for H. pylori positivity in lymphoma, with six cases (2.3%).

Table 2. Summary of H. pylori detection (in numbers) in different regions.

| Normal tissue | Ulcerative/Inflammatory lesion | SCC | Lymphoma | |||||

| H. pylori status | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | - |

| Buccal mucosa | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 1 |

| Floor of mouth | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Tongue | 1 | 3 | 26 | 13 | 13 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Tonsil | 1 | 2 | 37 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Retromolar area | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Gingiva | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Vestibule | 1 | 1 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Palate | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Soft palate | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Oropharynx | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Total | 12 | 20 | 85 | 32 | 69 | 14 | 17 | 11 |

Table 3shows that the highest frequency of H. pylori positivity was detected in ulcerative/inflammatory lesions in 85 (32.6%) cases, followed by OSCC in 69 (26.5%) cases. The highest frequency of H. pylori negativity was also seen in ulcerative/inflammatory lesions, with 32 cases (12.3%), followed by normal tissue, with 20 cases (7.6%).

Table 3. Frequency of H. pylori detection in different lesions.

| Type of Lesion | H. p Positive | H. p Negative | P |

| Normal tissue | 12 4.6% | 20 7.6% | All samples (0.000) |

| Ulcerative/Inflammatory lesions | 85 32.6% | 32 12.3% | All lesions (0.042) |

| SCC | 69 26.5% | 14 5.3% | |

| Lymphoma | 17 6.5% | 11 4.2% | |

| Total | 183 70.4% | 77 29.6% |

A summary of the presence of H. pylori in different tissue types is shown in Table 4. In all the lesions, H. pylori was mostly detected in the epithelium, with 181 cases (69.6%), followed by the lamina propria, with 86 cases (33.4%). In 19 (7.3%) cases, H. pylori was detected in blood vessels, in 11 cases (4.2%) in salivary gland ducts and in one case (0.3%) in the muscle layer of the tongue.

Table 4. Summary of H. pylori detection in different tissue types.

| Type of tissue Type of lesion | Epithelium | Lamina propria | Blood vessel | Salivary gland duct | Muscle layer |

| Normal tissue | 12 (14.6%) | 10 (3.8%) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Ulcerative/Inflammatory Lesions | 85 (32.7%) | 35 (13.4%) | 7 | 9 | 1 |

| SCC | 67 (25.6%) | 32 (12.3%) | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| Lymphoma | 17 (6.5%) | 10 (3.8%) | 3 | 1 | 0 |

As shown in Table 4, H. pylori epithelial positivity was mostly detected in ulcerative/inflammatory lesions in 85 cases (22.3%), followed by SCC in 67 cases (25.7%). Invasion to the lamina propria was also mostly detected in ulcerative/inflammatory lesions in 35 cases (13.5%), followed by SCC in 32 cases (12.3%).

Chi-squared test showed significant differences between the frequency of H. pylori positivity in normal tissues and the lesions examined (P=0.000). In addition, there was a statistically significant difference between the lesions examined (P=0.042).

Chi-squared test showed significant differences between H. pylori positivity and different tissue types except for intramuscular layer as follows: in the epithelium and in lamina propria (P=0.000), inside the blood vessels (P=0.003), inside salivary gland ducts (P=0.036), and muscle layer (P=0.122).

Discussion

In this study, the presence of H. pylori in normal oral tissues and oral lesions, ulcerative/inflammatory lesions, SCC and primary lymphoma were reviewed using IHC.

There are several methods to detect H. pylori. One of these is the urease test. But, in the oral cavity, there are other bacteria producing urease, including Streptococcus spp, Haemophilus spp and Actinomyces spp; therefore, it is hard to suggest that high urease activity in the oral cavity is indicative of the presence of H. pylori.21

In the stomach, culture technique has been considered “the gold standard.” However, contrary to the stomach, there are many other organisms in the oral cavity. Therefore, there is a possibility of other faster-growing organisms in the culture media.21 On the other hand, in the oral cavity, the organisms in coccoid forms are nonculturable; therefore, the prevalence of H. pylori may be underestimated.22Additionally, some previous studies have indicated that culture methods could very rarely isolate H. pylori from saliva. Some previous studies have shown that other microorganisms prevent H. pylori from growing in the culture media.23,24

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is another accurate method for detecting H. pylori; however, because different primers are used, the results are variable. In addition, due to false-positive results, partly due to the detection of cDNA from non-H. pylori organisms, the results are not reliable.12,21,25 In case of a low number of organisms in the specimen, false-negative results may also occur.26 On the other hand, in the oral cavity, there is a complexity of microflora; hence, the specificity and sensitivity of selected primers are another important issue.10 To increase the specificity of PCR and to avoid inhibitors, H. pylori should be separated from the contaminants.27 The other problem is that because H. pylori gene can be detected using PCR, it is not clear whether the gene found belongs to live bacteria or not.21,28 PCR detects the DNA of bacteria that are also not viable. PCR also detects small numbers of bacteria that may not have a significant impact on oral cavity infections.11 PCR assays for H. pylori have a wide cross-reactivity and are positive when other microorganisms contain those sequences.29Finally, it is difficult to find sufficient patients with OSCC and oral primary lymphoma within a reasonable time frame.

IHC is another method for detecting H. pylori. Ito et al used reverse transcriptase PCR to detect H. pylori DNA in the histologic sections and compared the results with those obtained using IHC. They found that IHC is specific but less sensitive than PCR.30

In the present study, firstly, due to IHC specificity for H. Pylori detection and, secondly, due to the decision to show the location of H. pylori inside the tissue as well as its invasion to the lamina propria, IHC was employed to detect H. pylori.

H. pylori was detected in different regions of the oral cavity, in descending order, as follows: dental plaque, 82.3%, gargles, 51.1% and mucosa of the dorsum of the tongue, 37.5%, suggesting that H. pylori settles in more than one site.31 The number of microorganisms varies from one site to another within the oral cavity and is not uniformly distributed in the mouth.32

Two mechanisms have been suggested for H. pylori pathogenesis. First, H. pylori interacts with surface epithelial cells, developing direct cell damage or producing pro-inflammatory mediators.33-35 Second, H. pylori reaches the underlying mucosa to stimulate an immune response, leading to the release of different cytokines and oxygen radicals that transform the chronic gastritis into gastroduodenal ulcers and gastric carcinoma.36-38 According to previous reports, H. pylori produces extracellular products that cause local and systemic immune responses, which can result in tissue damage.39-41 Previous studies on the gastric mucosa indicated the presence of H. pylori in the lamina propria, the intercellular space as well as in the gastric lumen.42H. Pylori was also detected inside the blood vessels, which may explain H. pylori bacteremia, resulting in a systemic response.43

Intercellular H. pylori was found in duodenal ulcer samples.44,45 In areas like an ulcerated epithelium, H. pylori gets serum factors and therefore becomes more invasive.46

H. pylori can be found within the oral epithelium, such as buccal mucosa and the tongue.17,47In the present study, one case of a normal tonsil and 37 cases of ulcerated/inflammatory tonsils showed H. pylori positivity. In a study on 23 samples from tonsil and adenoid tissues, H. pylori was detected in seven samples (30%, four tonsil tissues and three adenoid tissues).48

In the current study, H. pylori was detected in 4.6% of normal samples and in 32.7% of ulcerative/inflammatory lesions. In a study on oral ulcers, H. pylori was detected in six (20.7%) out of 29 cases, and all the positive samples were located in the buccal mucosa.47 In another study, Mravak-Stipetic et al, using PCR, detected H. pylori in four patients (12.5%) with recurrent aphthous ulcers. All the control samples were negative.16 In another study on recurrent aphthous ulcers, 71.9% of cases were positive for H. pylori.49Fritscher et al, studying 105 children and adolescents, found that 9.4% of 53 patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis were positive for H. Pylori, and in the control group only 3.8% were positive. They did not find any statistically significant relationship between the presence of H. Pylori and recurrent aphthous stomatitis.50

In our series, 26.5% of SCCs and 6.5% of lymphomas showed H. pylori positivity. Rubin et al, working on 61 samples from head and neck malignant and premalignant conditions, detected H. pylori positivity in 16.3% of oral cavity samples.17In a study using swab samples of the oral mucosa and cancer lesion surfaces, no positive PCR results were obtained.24According to previous reports, oral cancer has a high risk of secondary primary tumors. Patients surviving a previous oral cancer have up to a 20-fold increased risk of developing a second primary oral cancer.51,52 Poor oral hygiene increases the risk of oral cancer.53

A recent study reported that 40% of 39 patients had viable H. pylori in their oral cavities despite H. pylori eradication. In addition, 56% of those without detectable H. pylori in the mouth before treatment had H. pylori in the oral cavity when re-examined after H. pylori eradication.54Presence of H. pylori in the oral cavity, even after treatment, might explain the development of secondary primary tumors. It has been shown that H. pylori can multiply not only in macrophages but also in dendritic cells and epithelial cells. Residency inside infected cells increases its resistance to antimicrobial treatment and protects it from humoral antibody attack.16These findings can explain treatment failure.

The presence of H. pylori in the stromal cell of the lamina propria, far from the epithelial basement membrane, indicates invasion.55 Several studies have shown H. pylori invasion into the lamina propria of gastric mucosa, which can be an important factor in the induction and development of gastric inflammation.30,33,35,46In the present investigation, H. pylori was found in the epithelial layer of normal tissues as well as lesions in 69.6% and in the lamina propria in 33.4%, which can be clear evidence for the invasion of the bacteria. In one case, bacteria were found in the deep muscle layers of the tongue. Petersen et al found that H. pylori is able to pass through the endothelial layer.46 In the current study, in 7.3% of cases H. pylori was seen in the vessels, and it was also found in the salivary ducts in two cases.

In the present study, H. pylori oral colonization was seen in both the coccoid and the spiral forms. There are some other studies detecting H. pylori in the coccoid form. Many investigations have described whole bacterial cells, mainly of coccoid forms. The coccoid form of H. pylori is viable, but is not culturable and increases as infection proceeds. The coccoid form is more resistant to antibiotics and can spread to infect other cells in the absence of a therapeutic concentration of antibiotic.56 Wang et al suggested that the coccoid form of H. pylori is viable and maintains the integrity of the nucleic acid contents and active protein synthesis.57 In addition, the coccoid form of the microorganism is able to synthesize DNA.22 The present study detected the coccoid form of H. pylori, which might be proof for its long-standing persistence in the oral cavity and might reveal the role of H. pylori in the pathogenesis of the oral disorders examined. In this study, colonization and irregularly shaped bacteria and irregular dense bodies were found. Spiral, coccoid and degenerative forms and also irregularly shaped bacteria were found in other studies using electron microscopy.42

In the present study, in patients’ files, there were no clinical reports for gastritis or other stomach disorders. Several studies support the hypothesis that the oral cavity is a reservoir for re-infection of the stomach.21,58 On the other hand, some other investigations have shown that presence of H. pylori in the oral cavity does not relate to gastric infection and that H. pylori can also be found in the oral cavity without any gastric infection.14,32,54,59 In a study carried out by Song et al, it was shown that H. pylori DNA sequences differed between oral samples and gastric samples within the same individual.60

In conclusion, it is suggested that there is a relation between the presence of H. pylori in the oral cavity and in the oral lesions. It seems likely that the presence of H. pylori might be a risk factor for the developing oral lesions, ulcers and cancers. Oral infection sources such as dental plaque must be controlled to decrease the prevalence of oral cancer. The oral flora might be a diagnostic tool to predict oral lesions, such as oral cancer. Early detection and eradication of H. pylori in the oral cavity, especially in high-risk patients such as tobacco users, alcohol consumers, any patients with a history of gastritis or with cancer development in relatives, might prevent its consequences.

References

- 1.Johnson NW, Jayasekara P, Amarasinghe AA. Squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions of the oral cavity: Epidemiology and etiology. Periodontol 2000 . 2011;57:19–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scully C. Oral squamous cell carcinoma; from an hypothesis about a virus, to concern about possible sexual transmission. Oral Oncol . 2002;38:227–34. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(01)00098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lissowska J, PilarskaA PilarskaA, Pilarski P, Samolczyk-Wanyura D, Piekarczyk J, Bardin-Mikolłajczak A. et al. Smoking, alcohol, diet, dentition and sexual practices in the epidemiology of oral cancer in Poland. Eur J Cancer Prev . 2003;12:25–33. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallin KL, Wiklund F, Luostarinen T, Angström T, Anttila T, Bergman F. et al. A population-based prospective study of Chlamydia trachomatis infection and cervical carcinoma. Int J Cancer . 2002;1:371–4. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagy KN, Sonkodi I, Szöke I, Nagy E, Newman HN. The microflora associated with human oral carcinomas. Oral Oncol . 1998;34:304–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mager DL, Haffajee AD, Devlin PM, Norris CM, Posner MR, Goodson JM. The salivary microbiota as a diagnostic indicator of oral cancer: A descriptive, non-randomized study of cancer-free and oral squamous cell carcinoma subjects. J Transl Med . 2005;7:27–34. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mager DL, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Effects of periodon-titis and smoking on the microbiota of oral mucous mem-branes and saliva in systemically healthy subjects. J Clin Pe-riodontol. 2003;30:1031–7. doi: 10.1046/j.0303-6979.2003.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet . 1984;1:1311–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gebara EC, Pannuti C, Faria CM, Chehter L, Mayer MP, Lima LA. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori detected by polymerase chain reaction in the oral cavity of periodontitis patients. Oral MicrobiolImmunol . 2004;19:277–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2004.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song Q, Haller B, Schmid RM, Adler G, Bode G. Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque: A comparison of different PCR primer sets. Dig Dis Sci . 1999;44:479–84. doi: 10.1023/a:1026680618122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pytko-Polonczyk J, Konturek SJ, Karczewska E, Bielański W, Kaczmarczyk-Stachowska A. Oral cavity as permanent reservoir of Helicobacter pylori and potential source of reinfection. J PhysiolPharmacol . 1996;47:121–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Bielanski W, Guzik TJ, Loster B, Konturek SJ. Helicobacter pylori in the oral cavity and its implications for gastric infection, periodontal health, immunology and dyspepsia. J PhysiolPharmacol . 2005;56:77–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Butt AK, Khan AA, Khan AA, Izhar M, Alam A, Shah SW, Shafqat F. Correlation of Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque and gastric mucosa of dyspeptic patients. J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52:196–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ChitsaziMT ChitsaziMT, Fattahi E, Farahani RM, FattahiS FattahiS. Helicobacter pylori in the dental plaque: Is it of diagnostic value for gastric infection? Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2006;11:E325-8. Is it of diagnostic value for gastric infection? Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal . 2006;11: Is it of diagnostic value for gastric infection? Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2006;11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silva DG, Stevens RH, Macedo JM, Albano RM, Falabella ME, Fischer RG, Veerman EC, Tinoco EM. Presence of Helicobacter pylori in supragingival dental plaque of indi-viduals with periodontal disease and upper gastric diseases. Arch Oral Biol. 2010;55:896–901. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mravak-Stipetić M, Gall-Troselj K, Lukac J, Kusić Z, Pavelić K, Pavelić J. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in various oral lesions by nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR) J Oral Pathol Med . 1998;27:1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1998.tb02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin JS, Benjamin E, Prior A, Lavy J. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in malignant and premalignant conditions of the head and neck. J LaryngolOtol . 2003;117:118–21. doi: 10.1258/002221503762624558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehours P, Yilmaz O. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter . 2007;12Suppl 1:1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst PB, Gold BD. The disease spectrum of Helicobacter pylori: The immunopathogenesis of gastro-duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer. Annu Rev Microbiol . 2000;54:615–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuipers EJ. Review article: exploring the link between Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Aliment PharmacolTher . 1999;13Suppl 1:3–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dowsett SA, Kowolik MJ. Oral Helicobacter pylori: Can we stomach it? Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003;14:226-33. Can we stomach it? Crit Rev Oral Biol Med . 2003;14: Can we stomach it? Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003;14. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bode G, Mauch F, Malfertheiner P. Bode G, Mauch F, Malfertheiner PThe coccoid forms of Helicobacter pyloriCriteria for their viability. Epidemiol Infect . 1993;111:483–90. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800057216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishihara K, Miura T, Kimizuka R, Ebihara Y, Mizuno Y, Okuda K. Oral bacteria inhibit Helicobacter pylori growth. FEMS MicrobiolLett . 1997;152:355–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okuda K, Ishihara K, Miura T, Katakura A, Noma H, Ebihara Y. Helicobacter pylori may have only a transient presence in the oral cavity and on the surface of oral cancer. MicrobiolImmunol . 2000;44:385–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb02510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madinier IM, Fosse TM, Monteil RA. Oral carriage of Helicobacter pylori: A review. J Periodontol . 1997;68:2–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sugimoto M, Wu JY, Abudayyeh S, Hoffman J, Brahem H, Al-Khatib K. et al. Unreliability of results of PCR detection of Helicobacter pylori in clinical or environmental samples. J ClinMicrobiol . 2009;47:738–42. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01563-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ge Z, Taylor DE. Helicobacter pylori--molecular genetics and diagnostic typing. Br Med Bull . 1998;54:31–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enroth H, Engstrand L. Immunomagnetic separation and PCR for detection of Helicobacter pylori in water and stool specimens. J ClinMicrobiol . 1995;33:2162–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.8.2162-2165.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Zaatari FA, Nguyen AM, Genta RM, Klein PD, Graham DY. El-Zaatari FA, Nguyen AM, Genta RM, Klein PD, Graham DYDetermination of Helicobacter pylori status by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reactionComparison with urea breathe test. Dig Dis Sci . 1995;40:109–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02063952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito T, Kobayashi D, Uchida K, Takemura T, Nagaoka S, Kobayashi I. et al. Helicobacter pylori invades the gastric mucosa and translocates to the gastric lymph nodes. Lab Invest . 2008;88:664–81. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao J, Li Y, Wang Q, Qi C, Zhu S. Correlation between distribution of Helicobacter pylori in oral cavity and chronic stomach conditions. J HuazhongUnivSciTechnolog Med Sci . 2011;31:409–12. doi: 10.1007/s11596-011-0391-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song Q, Lange T, Spahr A, Adler G, Bode G. Characteristic distribution pattern of Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque and saliva detected with nested PCR. J Med Microbiol . 2000;49:349–53. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-4-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amieva MR, Vogelmann R, Covacci A, Tompkins LS, Nelson WJ, Falkow S. Disruption of the epithelial apical-junctional complex by Helicobacter pylori Cag A. Science . 2003;300:1430–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1081919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Naumann M, Crabtree JE. Helicobacter pylori-induced epithelial cell signalling in gastric carcinogenesis. Trends Microbiol . 2004;12:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peek RM Jr. Peek RM JrIVHelicobacter pylori strain-specific activation of signal transduction cascades related to gastric inflammation. Am J PhysiolGastrointest Liver Physiol . 2001;280:G525–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.4.G525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baik SC, Youn HS, Chung MH, Lee WK, Cho MJ, Ko GH. et al. Increased oxidative DNA damage in Helicobacter pylori-infected human gastric mucosa. Cancer Res . 1996;56:1279–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han BG, Kim HS, Rhee KH, Han HS, Chung MH. Effects of rebamipide on gastric cell damage by Helicobacter pylori-stimulated human neutrophils. Pharmacol Res . 1995;32:201–7. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(05)80023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Youn HS, Ko GH, Chung MH, Lee WK, Cho MJ, Rhee KH. Pathogenesis and prevention of stomach cancer. J Korean Med Sci . 1996;11:373–85. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1996.11.5.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perez-Perez GI, Dworkin BM, Chodos JE, Blaser MJ. Campylobacter pylori antibodies in humans. Ann Intern Med . 1988;109:11–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Negrini R, Savio A, Appelmelk BJ. Autoantibodies to gastric mucosa in Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter . 1997;2Suppl 1:S13–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.1997.06b05.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sudhakar U, Anusuya CN, Ramakrishnan T, Vijayalakshmi R. Isolation of Helicobacter pylori from dental plaque: A microbiological study. J Indian SocPeriodontol . 2008;12:67–72. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.44098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Necchi V, Candusso ME, Tava F, Luinetti O, Ventura U, Fiocca R. et al. Intracellular, intercellular, and stromal invasion of gastric mucosa, preneoplastic lesions, and cancer by Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology . 2007;132:1009–23. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ndawula EM, Owen RJ, Mihr G, Borman P, Hurtado A. Helicobacter pylori bacteraemia. Eur J ClinMicrobiol Infect Dis . 1994;13:621. doi: 10.1007/BF01971319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bode G, Malfertheiner P, Ditschuneit H. Pathogenetic implications of ultrastructural findings in Campylobacter pylori related gastroduodenal disease. Scand J GastroenterolSuppl . 1988;142:25–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bode G, Malfertheiner P, Ditschuneit H. Invasion of campylobacter-like organisms in the duodenal mucosa in patients with active duodenal ulcer. KlinWochenschr . 1987;65:144–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01728609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petersen AM, Krogfelt KA. Helicobacter pylori: An invading microorganism? A review. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol . 2003;36:117–26. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leimola-Virtanen R, Happonen RP, Syrjänen S. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Helicobacter pylori (HP) found in oral mucosal ulcers. J Oral Pathol Med . 1995;24:14–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1995.tb01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cirak MY, Ozdek A, Yilmaz D, Bayiz U, Samim E, Turet S. Detection of Helicobacter pylori and its Cag A gene in tonsil and adenoid tissues by PCR. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2003;129:1225–9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.11.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Birek C, Grandhi R, McNeill K, Singer D, Ficarra G, Bowden G. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in oral aphthous ulcers. J Oral Pathol Med . 1999;28:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb02024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fritscher AM, Cherubini K, Chies J, Dias AC. Association between Helicobacter pylori and recurrent aphthous stomatitis in children and adolescents. J Oral Pathol Med . 2004;33:129–32. doi: 10.1111/j.0904-2512.2004.00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Braakhuis BJ, Tabor MP, Leemans CR, van der Waal, Snow GB, Brakenhoff RH. Second primary tumors and field cancerization in oral and oropharyngeal cancer: Molecular techniques provide new insights and definitions. Head Neck . 2002;24:198–206. doi: 10.1002/hed.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rennemo E, Zatterstrom U, Boysen M. Impact of second primary tumors on survival in head and neck cancer: An analysis of 2,063 cases. Laryngoscope . 2008;118:1350–6. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318172ef9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marshall JR, Graham S, Haughey BP, Shedd D, O'Shea R, Brasure J. et al. Smoking, alcohol, dentition and diet in the epidemiology of oral cancer. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol . 1992;28B:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(92)90005-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Loster B, Bielanski W, Guzik TJ, Konturek PC, Zapala J. et al. Implications of oral Helicobacter pylori for the outcome of its gastric eradication therapy. J ClinGastroenterol . 2007;41:145–51. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225654.85060.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ko GH, Kang SM, Kim YK, Lee JH, Park CK, Youn HS. et al. Invasiveness of Helicobacter pylori into human gastric mucosa. Helicobacter . 1999;4:77–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1999.98690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chu YT, Wang YH, Wu JJ, Lei HY. Invasion and multiplication of Helicobacter pylori in gastric epithelial cells and implications for antibiotic resistance. Infect Immun . 2010;78:4157–65. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00524-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang XF, Wang KX. Cloning and expression of vacA gene fragment of Helicobacter pylori with coccoid form. J Chin Med Assoc . 2004;67:549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oshowo A, Gillam D, Botha A, Tunio M, Holton J, Boulos P. et al. Helicobacter pylori: The mouth, stomach, and gut axis. Ann Periodontol . 1998;3:276–80. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Teoman I, Ozmeriç N, Ozcan G, Alaaddinoğlu E, Dumlu S, Akyön Y. et al. Comparison of different methods to detect Helicobacter pylori in the dental plaque of dyspeptic patients. Clin Oral Investig . 2007;11:201–5. doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Song Q, Spahr A, Schmid RM, Adler G, Bode G. Helicobacter pylori in the oral cavity: High prevalence and great DNA diversity. Dig Dis Sci . 2000;45:2162–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1026636519241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]