Abstract

Objectives. This study assessed possible associations between recessions and changes in the magnitude of social disparities in foregone health care, building on previous studies that have linked recessions to lowered health care use.

Methods. Data from the 2006 to 2010 waves of the National Health Interview Study were used to examine levels of foregone medical, dental and mental health care and prescribed medications. Differences by race/ethnicity and education were compared before the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, during the early recession, and later in the recession and in its immediate wake.

Results. Foregone care rose for working-aged adults overall in the 2 recessionary periods compared with the pre-recession. For multiple types of pre-recession care, foregoing care was more common for African Americans and Hispanics and less common for Asian Americans than for Whites. Less-educated individuals were more likely to forego all types of care pre-recession. Most disparities in foregone care were stable during the recession, though the African American–White gap in foregone medical care increased, as did the Hispanic–White gap and education gap in foregone dental care.

Conclusions. Our findings support the fundamental cause hypothesis, as even during a recession in which more advantaged groups may have had unusually high risk of losing financial assets and employer-provided health insurance, they maintained their relative advantage in access to health care. Attention to the macroeconomic context of social disparities in health care use is warranted.

The “Great Recession” of 2007 to 2009 has been called the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression, and generated negative shocks to employment and financial stability for many adults.1 Such shocks could lead individuals to restrict spending on needed goods and services, including health care. Some decreases were observed in the Great Recession; the percentage of working-age adults who delayed or did not receive needed medical care because of cost increased from 9% in 1999 to 15% in 2009.2 Use of specific types of care also declined, such as screening colonoscopies among commercially insured US adults aged 50 to 64 years.3 Such findings are consistent with evidence for declines in preventive services use4 and hospitalizations among working-aged adults5 from prior, less severe macroeconomic downturns. However, we know relatively little about the impact of recessions on social disparities in health care use.

Point-in-time studies in more typical macroeconomic periods have found that racial/ethnic minorities in the United States are more likely to forego care than are non-Hispanic Whites.6–10 Other studies have shown that some aspects of socioeconomic position, particularly income11,12 and health insurance coverage,13 are associated with foregone care. We know less about the patterning of educational disparities in foregone care, though educational attainment is a strong predictor of health insurance coverage and income. Because it is typically determined early in life, educational attainment is a relatively durable marker of socioeconomic position because employment status, health insurance coverage, income, and assets change throughout adulthood. Educational attainment may be a particularly useful indicator of access to a broad array of resources associated with access to care during the volatility of a deep recession.

Although previous studies have demonstrated racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in foregone health care, there has been less attention to the way disparities change with evolving macroeconomic conditions. The Great Recession could have affected levels of and disparities in health care use because it involved very high levels of employment disruptions, interruptions in employer-provided health insurance, and asset losses. These negative changes could increase the likelihood of foregone care for some groups more than others. On one hand, we might expect that because many racial/ethnic minorities and less-educated workers fared worse in the Great Recession in exposure to job loss and unemployment,1 their likelihood of foregoing care for cost reasons might have grown more than that of more educated or non-Hispanic White adults, widening existing disparities. On the other hand, the Great Recession could have reduced disparities because more advantaged groups with greater access to resources like employer-provided health insurance14,15 or substantial financial assets16 had the most to lose in this long and deep recession, and their likelihood of foregoing care may have increased more than that of groups without these resources. A final possibility is that levels of foregone care increased across all groups, even if for different reasons, and existing patterns of disparities persisted.

The few studies that have assessed the impact of the Great Recession on disparities in health care utilization suggest relatively little change in existing disparities. A study showed a downward trend in physician visits, prescription drug refills, and inpatient visits that was similar among Whites, African Americans and Hispanics, though office-based physician visits dropped more for Hispanics than for Whites, widening the racial/ethnic disparity.17 The likelihood of a dental visit in the past year also declined among US adults, as part of a longer-term decline, but substantially accelerated in the late 2000s among low-income individuals, widening the socioeconomic position disparity.18 This small amount of available evidence thus suggests increases in foregone care across the population during the Great Recession, with relatively stable or increased disparities when the likelihood rose faster among less-advantaged groups. However, more evidence on a wide variety of types of foregone care across US racial/ethnic and educational groups is needed. For example, types of care like dental care may be foregone before other types that are deemed more immediately necessary, such as prescribed medications.

In this study, we used National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data on US adults aged 25 to 64 years to compare levels of and disparities in foregone care before the Great Recession, early in the recession, and later and in the immediate wake of the recession. This large, nationally representative sample allows comparisons of Whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans of all educational levels. We assessed medical visits, dental visits, mental health care, and prescribed medications that were perceived as needed but were foregone because they were not affordable. This study thus builds on the extant literature by comparing across more racial/ethnic groups, considering educational disparities, and assessing a variety of types of health care to examine the consequences of the Great Recession for disparities in foregone care in the United States.

METHODS

We used data from the 2006 to 2010 waves of the NHIS, a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey conducted annually to assess health and other characteristics of noninstitutionalized individuals in the United States.19 We use data from interviews conducted from January 2006 to May 2010 to capture different periods of the late 2000s recession, and focus on sample adults aged 25 to 64 years, to capture those who were likely to have completed their education but were younger than retirement age. The Great Recession probably affected the health care use of older adults differently because of their access to Medicare. A sample of 75 600 respondents of this age range was available for this period, and after dropping respondents who were not in one of our 4 focal race/ethnicity categories (n = 755) and those missing on any key covariates (n = 656), we were left with an analytic sample of 73 403 to 74 204 respondents, depending on the outcome measure.

Measures

We examined 4 types of foregone care: foregone medical care, dental care, mental health care, and foregone prescription medicines. To measure foregone medical care, respondents were asked “During the past 12 months, was there any time when you needed medical care, but did not get it because you couldn't afford it?” Other types of foregone care were assessed using the question: “During the past 12 months, was there any time when you needed any of the following, but didn't get it because you couldn't afford it?” Respondents were then asked about “Dental care (including check ups),” “Mental health care or counseling,” and “Prescription medicines.” Responses for all questions about foregone care were coded 0 for no and 1 for yes.

To capture changes in levels and differences in foregone care, we categorized the period into 3 groups. May 2006 through November 2007 represents the prerecession period, ending the month before the National Bureau of Economic Research denoted the start of the recession. December 2007 through November 2008 represents the early recession period and includes the fall of the US stock market in late 2008. We categorized December 2008 through May 2010 as the recession and postrecession period; the National Bureau of Economic Research classified June 2009 as the last month of the recession, but many locales remained affected for months afterward. Additionally, because NHIS measures of foregone care refer to the past 12 months, we wanted to continue follow-up of these respondents for at least 11 months after the official end of the recession in case the foregone care they referred to occurred during the official recessionary period.

Self-reported main racial/ethnic background, using the pre-1997 Office of Management and Budget’s Statistical Policy Directive No. 15, Race and Ethnic Standards for Federal Statistics and Administrative Reporting, was collected. We measured Hispanic ethnicity with an item that asked: “Do you consider yourself to be Hispanic or Latino?” We devised a race/ethnicity variable with categories for non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic African Americans, Hispanics (of any race), and non-Hispanic Asian Americans. Other racial/ethnic groups were too small to consider. We measured educational attainment with an item that asked: “What is the highest level of school you have completed or the highest degree you have received?” We recoded responses into 4 categories: less than high school completion, high school graduate or GED, some college or associate’s degree, and bachelor’s degree or more. Age was categorized as 25 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, and 55 to 64 years. Female gender was coded 1; male was coded 0.

Analysis

We assessed bivariate associations by period between foregone care and racial/ethnic group or highest level of education. These estimates were predictive margins obtained from logistic regression models that adjusted for the focal predictor categories (race/ethnicity or education), categories for the early recession or recession and post-recession periods, and interactions between the focal predictor and period categories. We tested for statistical significance of differences between predictive margins by using the adjusted Wald test to assess whether there were differences across racial/ethnic or educational categories within period, and whether there were differences within categories (e.g., among African Americans) across periods. We also estimated multiple regression models to obtain predictive margins that could be used to conduct tests of difference-in-differences, so that we could assess whether racial/ethnic or educational disparities grew across periods. These logistic regression models adjusted for racial/ethnic and educational categories, period indicators, interactions between the racial/ethnic and educational categories and period categories, and age and gender. All analyses were conducted using survey estimation procedures in Stata version 12SE (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and weighted using individual sample weights provided by Integrated Health Interview Series investigators.19 A value of P < .05 was used to establish statistical significance.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the descriptive characteristics for the analytic sample by period. Table 2 shows the levels of foregone care by type across the 3 periods. The first column shows the predicted percent of respondents reporting each form of foregone care in the prerecession period, overall in the first set of rows and then by race/ethnicity and educational attainment in subsequent sets of rows. Subsequent columns indicate values for later periods. Among working-aged US adults before the Great Recession, there were substantial inequalities by race/ethnicity and education on most measures of foregone care, with African Americans and Hispanics more likely and Asian Americans less likely to forego care than Whites. Those with less than a bachelor’s degree were significantly more likely to report all types of forgone care.

TABLE 1—

Study Sample Characteristics by Recessionary Period Among Respondents Aged 25–64 Years: National Health Interview Study, United States, 2006–2010

| Characteristic | Prerecession, % | Early Recession, % | Recession and Postrecession, % | P |

| Educational Attainment | < .001 | |||

| < high school | 14.0 | 13.1 | 12.2 | |

| High school/GED | 27.8 | 26.2 | 26.3 | |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 27.9 | 29.3 | 30.1 | |

| ≥ bachelor’s degree | 30.4 | 31.4 | 31.5 | |

| Race/ethnicity | .619 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 69.2 | 68.5 | 68.2 | |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 12.0 | 12.1 | 12.2 | |

| Hispanic | 14.0 | 14.6 | 14.6 | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.0 | |

| Age, y | .01 | |||

| 25–34 | 25.4 | 25.1 | 25.2 | |

| 35–44 | 26.9 | 26.0 | 25.5 | |

| 45–54 | 27.5 | 27.7 | 27.6 | |

| 55–64 | 20.3 | 21.2 | 21.7 | |

| Female | 50.9 | 51.1 | 50.9 | .906 |

Note. GED = general equivalency diploma. Percentages are weighted. The sample size was n = 74 204. P values determined by χ2 test for difference across periods.

TABLE 2—

Predicted Percent Reporting Foregone Care by Type and Recessionary Period, Overall and by Race/Ethnicity and Educational Attainment Among Respondents Aged 25–64 Years: National Health Interview Study, United States, 2006–2010

| Prerecession |

Early Recession |

Recession and Postrecession |

||||||

| Variable | % | Group Difference Within Period, P | % | Group Difference Within Period, P | Difference From Prerecession, P | % | Group Difference Within Period, P | Difference From Prerecession, P |

| Overall | ||||||||

| Medical care | 8.65 | NA | 9.99 | NA | < .001 | 10.35 | NA | < .001 |

| Dental care | 13.32 | NA | 15.96 | NA | < .001 | 16.87 | NA | < .001 |

| Mental health | 2.81 | NA | 3.36 | NA | .006 | 3.39 | NA | .001 |

| Prescription medication | 9.42 | NA | 10.71 | NA | .001 | 11.53 | NA | < .001 |

| Medical visits (n = 74 204) | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 8.60 | … | 9.24 | … | .125 | 9.94 | … | < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 9.97 | .012 | 13.27 | < .001 | < .001 | 13.36 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 9.58 | .079 | 12.59 | < .001 | .001 | 12.09 | .001 | .001 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 3.32 | < .001 | 4.56 | < .001 | .17 | 3.41 | < .001 | .871 |

| < high school | 12.95 | < .001 | 15.77 | < .001 | .008 | 16.22 | < .001 | .001 |

| High school/GED | 9.87 | < .001 | 10.83 | < .001 | .148 | 11.91 | < .001 | .002 |

| Some college/associate’s degree | 9.87 | < .001 | 11.73 | < .001 | .004 | 11.92 | < .001 | < .001 |

| ≥ bachelor’s degree | 4.42 | … | 5.25 | … | .063 | 5.28 | … | .023 |

| Dental visits (n = 73 415) | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 12.86 | … | 14.75 | … | .001 | 15.85 | … | < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 15.20 | .004 | 19.07 | < .001 | .002 | 19.21 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Hispanic | 15.98 | < .001 | 21.54 | < .001 | < .001 | 22.46 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 7.55 | < .001 | 8.46 | < .001 | .476 | 8.57 | < .001 | .46 |

| < high school | 19.41 | < .001 | 23.06 | < .001 | .009 | 26.48 | < .001 | < .001 |

| High school/GED | 14.91 | < .001 | 18.60 | < .001 | < .001 | 19.31 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Some college/associate’s degree | 15.86 | < .001 | 17.80 | < .001 | .014 | 19.32 | < .001 | < .001 |

| ≥ bachelor’s degree | 6.77 | … | 9.07 | … | < .001 | 8.77 | … | < .001 |

| Mental health care (n = 73 403) | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2.84 | … | 3.23 | … | .114 | 3.46 | … | .004 |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 2.98 | .689 | 3.63 | .409 | .239 | 3.77 | .508 | .145 |

| Hispanic | 3.05 | .435 | 4.30 | .05 | .019 | 3.52 | .903 | .373 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.33 | < .001 | 1.74 | .022 | .545 | 1.02 | < .001 | .451 |

| < high school | 4.19 | < .001 | 4.84 | < .001 | .311 | 4.21 | < .001 | .971 |

| High school/GED | 3.14 | < .001 | 3.46 | < .001 | .429 | 3.76 | < .001 | .13 |

| Some college/associate’s degree | 3.29 | < .001 | 4.18 | < .001 | .031 | 4.16 | < .001 | .019 |

| ≥ bachelor’s degree | 1.45 | … | 1.90 | … | .119 | 2.02 | … | .014 |

| Prescription medication (n = 73 413) | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 8.81 | … | 9.55 | … | .103 | 10.72 | … | < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 12.52 | < .001 | 14.95 | < .001 | .049 | 15.24 | < .001 | .003 |

| Hispanic | 11.54 | < .001 | 14.67 | < .001 | .009 | 14.80 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 4.19 | < .001 | 4.69 | < .001 | .624 | 3.98 | < .001 | .81 |

| < high school | 15.91 | < .001 | 17.45 | < .001 | .182 | 18.85 | < .001 | .014 |

| High school/GED | 10.83 | < .001 | 12.99 | < .001 | .007 | 14.16 | < .001 | < .001 |

| Some college/associate’s degree | 11.00 | < .001 | 11.69 | < .001 | .353 | 13.41 | < .001 | < .001 |

| ≥ bachelor’s degree | 3.71 | … | 5.09 | … | .003 | 4.73 | … | .011 |

Note. GED = general equivalency diploma; NA = not applicable. Estimated percentages are weighted predictive margins obtained from logistic regression models that adjusted for the focal predictor categories (race/ethnicity or education), categories for the early recession or recession and post-recession periods, and interactions between the focal predictor and period categories.

Considering changes over time within racial/ethnic groups, foregone medical care was higher in both recessionary periods for African Americans and Hispanic respondents and for Whites in the recession and postrecession period. Turning to changes over time within education groups, foregone medical care was higher in the early recession for those with less than high school and some college, and was higher in the recession and postrecession period for all educational groups. Table 2 also indicates that foregone dental care differed significantly across racial/ethnic groups, with Asians reporting the least and Hispanics the most, and rose for all racial/ethnic groups across periods except Asian Americans. Less-educated respondents were more likely to forego dental care in every period, though foregone dental care rose across both periods for all education groups.

Levels of foregone mental health care were significantly lower for Asians than for Whites in all periods, although African Americans and Hispanics did not differ from Whites. Foregone mental health care rose for Hispanics from the prerecession to the early recession period, but then fell to levels not significantly different from the prerecession period. Foregoing mental health care was also significantly more likely among those with less than a bachelor’s degree across periods, and was significantly higher in both recessionary periods among those with some college and in the recession and postrecession period for those with a bachelor’s degree or more. Finally, reporting foregoing prescription medications was least likely in every period among Asians and most likely among African Americans. Foregoing medications was significantly more common among African Americans and Hispanics in both recessionary periods compared with the prerecession period, and among Whites in the recession and postrecession period. Foregoing prescription medications was more common among groups with less than a bachelor’s degree in all periods. Those with high school education and those with a bachelor’s degree or more showed higher levels in both recessionary periods, but all education groups showed higher levels in the recession and postrecession period.

We used multiple regression analyses to evaluate whether these disparities between racial/ethnic or education groups evident in Table 2 changed significantly across periods. The full results from the logistic regression models are shown in Appendix A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Table 3 shows P values for the difference-in-differences tests that reveal whether differences changed significantly. The first row indicates whether the gap between White and African American respondents in each type of foregone care was significantly different when considering the prerecession period versus the early recession period. The P value of .011 in the upper left cell of Table 3 signifies that this difference is statistically significant, and the P value of .031 in the cell below shows that the difference-in-difference comparison of the White–African American gap between the prerecession period and the recession and postrecession period was also significant. Table 3 shows that although some other comparisons were marginally significant, the only other statistically significant difference-in-difference tests were for the White–Hispanic gap in dental care from the prerecession period to the early recession period and for the less than high school–bachelor’s degree or more gap in dental care between the prerecession period and the recession and postrecession period.

TABLE 3—

P values for Tests of Difference-in-Difference Comparisons Among Respondents Aged 25–64 Years: National Health Interview Study, United States, 2006–2010

| Variable | Medical Care | Dental Care | Mental Health Care | Prescription Medication |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| African American vs White | ||||

| Prerecession vs early recession | .011 | .148 | .71 | .153 |

| Prerecession vs later recession | .031 | .642 | .832 | .593 |

| Hispanic vs White | ||||

| Prerecession vs early recession | .057 | .033 | .153 | .068 |

| Prerecession vs later recession | .458 | .072 | .98 | .323 |

| Asian vs White | ||||

| Prerecession vs early recession | .535 | .487 | .991 | .765 |

| Prerecession vs later recession | .127 | .304 | .06 | .067 |

| Educational Attainment | ||||

| < high school vs high school/GED | ||||

| Prerecession vs early recession | .352 | .544 | .936 | .391 |

| Prerecession vs later recession | .435 | .246 | .439 | .559 |

| < high school vs some college | ||||

| Prerecession vs early recession | .847 | .726 | .493 | .992 |

| Prerecession vs later recession | .43 | .073 | .273 | .893 |

| < high school vs ≥ bachelor’s degree | ||||

| Prerecession vs early recession | .341 | .932 | .912 | .592 |

| Prerecession vs later recession | .107 | .007 | .401 | .32 |

Note. GED = general equivalency diploma. P values refer to comparisons of predictive margins. Multiple regression models were estimated to obtain predictive margins, adjusted for racial/ethnic and educational categories, period indicators, interactions between the racial/ethnic and educational categories and period categories, and age and gender. Models and estimates were weighted and used survey estimation procedures.

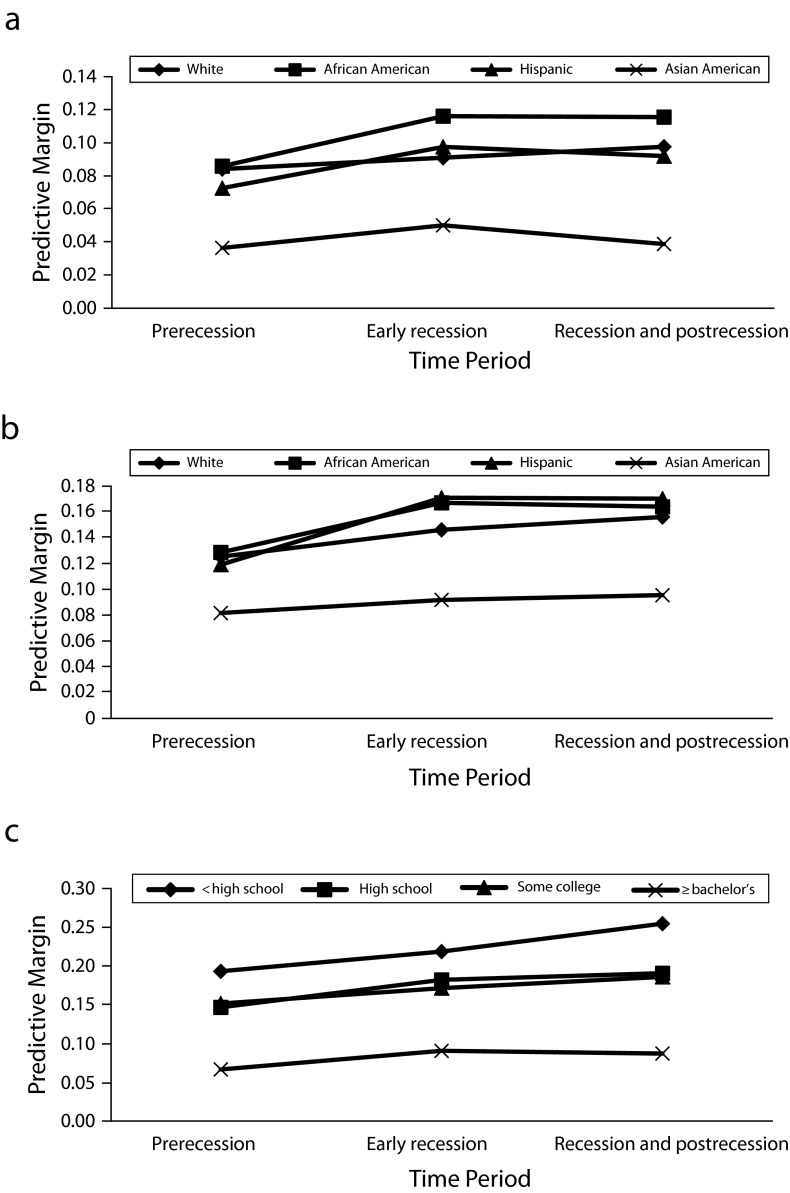

Figure 1 displays the predictive margins that illustrate the magnitude and direction of the significant difference-in-difference comparisons from Table 3. Figure 1a shows that as levels of foregone medical care were rising across most racial/ethnic groups, they were growing faster for African Americans. The difference between Whites and African Americans grew significantly and remained higher in both recessionary periods. Figure 1b shows that the gap between Whites and Hispanics in foregoing dental care grew from the prerecession to the early recession period, but then closed somewhat as levels continued to rise for Whites but not for Hispanics. Figure 1c shows the predicted proportion foregoing dental care by educational group, illustrating how disparities by education are even greater than those by race/ethnicity. Only about 6.8% of those with a bachelor’s degree did not obtain needed dental care in the prerecession period, compared with about 19.4% of those with less than a high school education. There was significant growth in the gap because foregone dental care increased more for those with the least education in both recessionary periods.

FIGURE 1—

Predictive margins by period for (a) foregone medical care by race/ethnicity, (b) foregone dental care by race/ethnicity, and (c) foregone dental care by educational attainment: National Health Interview Study, United States, 2006–2010.

DISCUSSION

Levels of foregone medical, dental, and mental health care and forgone prescribed medications rose for working-aged US adults in the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009. The likelihood of foregoing medical and dental care or prescribed medications rose at all levels of education and among Whites, African Americans, and Hispanics, though not among Asian Americans. In some comparisons with the prerecession period, levels of foregone mental health care rose for Whites, Hispanics, and those with some college or a bachelor’s degree or more. Because levels of foregone care were rising across groups in most cases, racial/ethnic and educational disparities in foregone care generally persisted from the prerecession through the early recession and the recession and postrecession periods we studied. However, the gap between African Americans and Whites grew as foregone medical care rose faster for African Americans. Similarly, levels of foregone dental care rose faster for Hispanics than for Whites, increasing that disparity temporarily. Finally, we noted that the least-educated respondents showed a faster rise in levels of foregone dental care, increasing the disparity with those holding a bachelor’s degree or more.

These findings are consistent with the limited prior evidence that US adults were using less health care in the Great Recession, leading to some increased disparities because less advantaged groups were using even less.17,18 However, our data allowed for novel findings. First, we found that levels of foregone care were lowest among Asian Americans, and their levels did not rise during the recessionary period. There are several potential explanations; Asian Americans, particularly immigrants, have better health on a variety of measures,10 so they may need less health care and thus be less likely to have to forego it even during a major macroeconomic shock. However, differences in perceived need for care or cultural or linguistic barriers may play a role. Evidence from other studies has shown that Asian Americans are less likely to use mental health services than other racial/ethnic groups, and some have argued that reluctance to seek services is a better explanation than lack of need.20 Our study cannot adjudicate between these possibilities, but suggests the importance of continuing to considering a broader range of racial/ethnic group-based disparities in studies of access to care. Moreover, there are high levels of heterogeneity in health care need and socioeconomic resources within the broad Hispanic and Asian American racial/ethnic groups, and future studies with larger samples should address this variation. A key source of variation is immigrant status and acculturation, and we conducted a similar set of analyses (not shown) including only those born in the United States to assess the impact on our findings. These results showed that when considering only native-born respondents, Hispanic levels of foregone medical care were higher, and similar to those of African Americans, but the relative gaps with Whites did not change substantially across periods from those in the total sample. A notable difference was that native-born Asian Americans showed lower prerecession foregone dental care than native-born Whites, but increased much more quickly in the early recession period, significantly narrowing that disparity. Although more assessment of the roles of immigrant status and acculturation are needed in understanding these differences, most of the findings were very similar to those presented here for native- and foreign-born respondents.

Second, we examined educational disparities in foregone care, providing a new lens on dimensions of unequal access. Often these were slightly larger than disparities by race/ethnicity. In particular, respondents with less than a high school education were at very high risk for foregoing all forms of care, both before and during the recessionary periods. Nearly every educational disparity persisted over the Great Recession, with only 1 gap that increased. These findings are consistent with fundamental cause theory, a prominent explanation for the persistent link between socioeconomic status and health.21 Empirical tests of the theory have shown that high–socioeconomic status individuals have maintained their health advantage across recent history because as new resources for health maintenance become available, they are better able to take advantage, and as new disease threats emerge, they are able to more quickly address them with a multitude of resources and through a plethora of mechanisms. In this article, we considered how a different kind of exogenous threat to health—a major economic recession—affected more- and less-advantaged US adults. We discovered that more highly educated individuals maintained their relative advantage, even though they had a higher risk of losing important resources like employer provided health insurance or financial assets like homes or stock investment earnings. It will be important to monitor socioeconomic disparities in foregone care after the slow recovery from the Great Recession. If more socioeconomically advantaged US adults enjoy a quicker recovery, social disparities in foregone care could widen in the coming years. Finally, we showed that socially disadvantaged US adults continued to be more likely to forego a wide variety of important types of health care in the Great Recession.

Limitations

Although we provided novel evidence about the levels of and changes in disparities in foregone health care in the Great Recession, these analyses cannot answer deeper questions about why disparities remained relatively stable. Future studies should consider how potentially varying underlying factors drove increases in foregone care within most groups, from Hispanics to those with a bachelor’s degree or more, and why Asian Americans appeared to be protected from macroeconomic volatility. Strong designs would consider within-person changes over time in the individual, household, community, and state and federal resources important for access to health, an approach not possible with NHIS data. As in many studies of foregone health care, we were unable to carefully address whether respondents reported not foregoing care for cost reasons because they did not face cost barriers or because did not need health care. Considering how social disparities in foregone care are driven by changes in the perceived or actual need for health care, versus changes in barriers to care, will be an important area for future research on health impacts of recessions.

Finally, we focused on working-aged US adults, but foregone care among younger and older individuals may also have changed. Because of federal programs, these groups have fundamentally different access to health care and may have been less affected by Great Recession through the mechanisms we speculate about here. However, future studies should consider how children and older adults are affected by their own and by working-aged providers’ recessionary experiences, and how household choices about health care consumption could vary by race/ethnicity or socioeconomic position in ways that shape evolving disparities.

Conclusions

Healthy People 2020 identified the goals of reducing foregone health care and racial/ethnic and socioeconomic status disparities in health and health care access. Understanding how and why levels and disparities in foregone care have been evolving in response to events like the Great Recession is important for these goals.

Acknowledgments

S. A. Burgard was supported by core funding from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant R24 HD041028 to the Population Studies Center, University of Michigan).

Human Participant Protection

Data were publicly available and deidentified, so human participant approval was not necessary.

References

- 1.Grusky DB, Western B, Wimer C, editors. The Great Recession. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Center for Health Statistics. Delayed or forgone medical care because of cost concerns among adults aged 18–64 years, by disability and health insurance coverage status—National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(44):1456.

- 3.Dorn SD, Wei D, Farley JF et al. Impact of the 2008–2009 economic recession on screening colonoscopy utilization among the insured. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(3):278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruhm CJ. Are recessions good for your health? Q J Econ. 2000;115(2):617–650. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruhm CJ. Good times make you sick. J Health Econ. 2003;22(4):637–658. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKee D, Fletcher J. Primary care for urban adolescent girls from ethnically diverse populations: foregone care and access to confidential care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(4):759–774. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rew L, Resnick M, Beuhring T. Usual sources, patterns of utilization, and foregone health care among Hispanic adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1999;25(6):407–413. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blendon R, Aiken L, Freeman H, Corey C. Access to medical care for Black and White Americans: a matter of continuing concern. JAMA. 1989;261(2):278–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford CA, Bearman PS, Moody J. Foregone health care among adolescents. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2227–2234. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu SM, Huang ZJ, Singh GK. Health status and health services utilization among US Chinese, Asian Indian, Filipino, and Other Asian/Pacific Islander children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1):101–107. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mielck A, Kiess R, Knesebeck O, Stirbu I, Kunst A. Association between forgone care and household income among the elderly in five Western European countries—analyses based on survey data from the SHARE-study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):52. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kullgren J, Galbraith A, Hinrichsen V et al. Health care use and decision making among lower-income families in high-deductible health plans. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(21):1918–1925. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson MJ, DeVoe J, Wright BJ. Short-term impacts of coverage loss in a Medicaid population: early results from a prospective cohort study of the Oregon health plan. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4(5):391–398. doi: 10.1370/afm.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keene JR, Prokos AH. Comparing offers and takeups of employee health insurance across race, gender, and decade. Sociol Inq. 2007;77(3):425–459. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seccombe K, Amey C. Playing by the rules and losing: health insurance and the working poor. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(2):168–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith JP. Racial and ethnic differences in wealth in the Health and Retirement Study. J Hum Resour. 1995;30:S158–S183. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mortensen K, Chen J. The Great Recession and racial and ethnic disparities in health services use. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):315–317. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wall TP, Vujicic M, Nasseh K. Recent trends in the utilization of dental care in the United States. J Dent Educ. 2012;76(8):1020–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minnesota Population Center and State Health Access Data Assistance Center. Integrated Health Interview Series: Version 5.0. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang AY, Snowden LR, Sue S. Differences between Asian and White Americans’ help seeking and utilization patterns in the Los Angeles area. J Community Psychol. 1998;26(4):317–326. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;35:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]