Abstract

Objectives. We examined the prevalence and associations between behavioral and identity dimensions of sexual orientation among adolescents in the United States, with consideration of differences associated with race/ethnicity, sex, and age.

Methods. We used pooled data from 2005 and 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Surveys to estimate prevalence of sexual orientation variables within demographic sub-groups. We used multilevel logistic regression models to test differences in the association between sexual orientation identity and sexual behavior across groups.

Results. There was substantial incongruence between behavioral and identity dimensions of sexual orientation, which varied across sex and race/ethnicity. Whereas girls were more likely to identify as bisexual, boys showed a stronger association between same-sex behavior and a bisexual identity. The pattern of association of age with sexual orientation differed between boys and girls.

Conclusions. Our results highlight demographic differences between 2 sexual orientation dimensions, and their congruence, among 13- to 18-year-old adolescents. Future research is needed to better understand the implications of such differences, particularly in the realm of health and health disparities.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently called for increased data collection on the lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) community in population health studies.1 Although numerous studies have identified sexual orientation health disparities among youths,2–9 researchers have only more recently begun to question if there is variation in prevalence of health outcomes among LGB populations depending on which dimension of sexual orientation is used (i.e., identity, behavior, or attraction).10 Sexual orientation is a multidimensional construct,11,12 and how it is measured changes the prevalence of nonheterosexual orientations.13,14 Large studies of probability samples of youths typically only include 1 item assessing a single dimension of sexual orientation,15 and, therefore, it is important to understand the level of congruency across these items.

The IOM report also called for the use of an intersectional perspective, which is one that recognizes an individual’s co-occurring social identities and how they interact with sexual orientation.1 Along these lines, there is much interest in the basic question of how different dimensions of sexual orientation are interrelated and if these relationships vary across development, sex, and race/ethnicity.11,12,16 Understanding how various dimensions of sexual orientation are interrelated, and if this varies across demographic groups, has important implications for our basic understanding of the development of sexual orientation and its measurement in future adolescent health research.

There is a growing body of research on incongruence between sexual orientation identity and sexual behaviors.13,17,18 A Canadian study found that 12% of 1878 adolescents endorsed at least 1 dimension of nonheterosexuality.13 Of these students, discrepancies were evident in their reports of sexual identity, attraction, and behavior; the majority only selected a single item (62%) whereas only 15% endorsed all items. The second-largest group (35%) was youths who reported same-sex attractions but no same-sex behavior or minority identity labels. From a developmental perspective it is important to recognize that sexual attractions typically emerge during early adolescence, whereas sexual behavior and internal adoption of identity labels occur during middle-to-late adolescence.11 These patterns reflect the complexity in researching youths’ sexual orientation as adolescents’ identity may be in flux and opportunities for sexual expression may not exist.11,12

A number of studies have found that girls are more likely to adopt both-sex–oriented identities (i.e., bisexual or mostly heterosexual) and to report same-sex attraction and same-sex sexual behavior.13,19,20 Studies have also found lower levels of congruence between identity and behavior among adult women compared with men,21,22 leading some to hypothesize that female sexual orientation is more fluid or plastic.23,24 Studies of sex differences in sexual orientation stability across development have not been fully supportive of this hypothesis as results have been inconsistent, with some studies finding greater stability of identity among sexual-minority girls,25,26 no sex differences among sexual minorities,27 or that it depends on sexual orientation.20

There has been limited research on how the experience of being LGB varies across racial or ethnic groups. Lack of significant differences in the timing of psychosexual milestones or in sexual identity formation among Black, Asian, Latino, and White youths has been reported,28–30 whereas others have found differences.31,32 Factors such as internalized homophobia, perceptions of rejection, and limited availability of support resources have been hypothesized to delay the timing of identity labeling and disclosure among racial/ethnic minority youths and thereby potentially produce less concordance among dimensions of sexual orientation.33,34 However, little research has examined how associations among different dimensions of sexual orientation may differ by race/ethnicity among adolescents.

There are crucial gaps in our knowledge of the congruence among the dimensions of sexual orientation among youths, which have an impact on our understanding of measurement of sexual orientation and, by extension, characterization of health disparities. This is primarily attributable to the small number of sexual minority individuals in most probability samples, which typically do not permit exploring variation within the LGB sample. The objective of this study was to examine the congruency of sexual orientation identity and behavior across sex, race/ethnicity, and development in a probability sample of adolescents achieved through pooling Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data.35

METHODS

We analyzed pooled data from the 2005 and 2007 YRBS, a biennial cross-sectional survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) among US high-school students using probabilistic sampling methods.36 The general approach to YRBS data collection, creation of the pooled data set, and characteristics of the sample by jurisdiction are described in detail elsewhere in this issue.35

As this study was focused on the association between sexual identity and sexual behavior, our analysis was limited to jurisdictions that collected both of these variables. Of the 14 jurisdictions, 8 included both measures. These jurisdictions and timepoints used for analysis were Boston, Massachusetts, 2005 and 2007; Chicago, Illinois, 2005 and 2007; Delaware 2005 and 2007; Maine 2007; Massachusetts 2005 and 2007; New York City, New York, 2005 and 2007; Rhode Island 2007; and Vermont 2005 and 2007 (n = 56 167). After data cleaning, which included deleting individuals who were aged 12 years and younger (n = 245), those who were in seventh grade or an unknown grade (n = 327), and those with missing data on 1 or more of the following variables: age (n = 270), sex (n = 449), race/ethnicity (n = 1481), sexual identity (n = 1784), and sexual behavior (n = 2309), we used a final pooled sample of 51 617 in the analyses.

Measures

All measures were assessed via self-report. Specific item wording for each jurisdiction and coding of sexual orientation and race/ethnicity items are described elsewhere in this issue.35 Sexual orientation identity measured whether respondents identified as heterosexual, bisexual, gay or lesbian, or unsure. The sexual behavior item measured whether respondents have had no sexual partners, opposite-sex–only sexual partners, both-sex sexual partners, or same-sex–only sexual partners. In most jurisdictions this item asked about “sexual contact,” but in Delaware and Vermont it asked about “sexual intercourse.” Measured demographic characteristics included sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic/Latino, Native American or Hawaiian, Asian, other), and age. The age variable was coded as each year of age from 13 to “18 or older.”

Statistical Analysis

We calculated descriptive statistics in SPSS version 20 (IBM, Armonk, NY) using the Complex Sampling Module to account for the complex sampling design of the YRBS by including sample weights, primary sampling units (PSU), and stratum variables. For these results we report unweighted sample sizes and weighted percentages. We used multilevel models, fit in HLM version 7 (Scientific Software International, Skokie, IL), to account for the clustering of participants within jurisdictions for inferential statistics. For analyses in HLM we adjusted YRBS sampling weights for these pooled analyses by using design effects calculated for each jurisdiction and year (see Mustanski et al.35 for further information).

We used 3 multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the associations between sexual orientation identity and sexual behavior, with interaction terms by sex and race/ethnicity used to determine if the association between these 2 measures of sexual orientation differed on the basis of demographics. In other words, sexual identity was treated as the dependent variable and sexual behavior, demographic characteristics, and their interaction were included as independent variables. For interaction terms in logistic regression each effect is conditional on independent variables within the model. To aid in interpretation of interactions in logistic models, effects were plotted and estimated separately by group (data not presented). For these analyses, we did not include youths who were abstinent or reported an identity label of “unsure.”

RESULTS

The sample ranged in age from 13 to 18 years (mean = 15.8; SD = 1.3). Table 1 shows the number and proportions of sexually active participants engaged in sexual activity with same- and opposite-sex partners clustered within identity subgroupings and major demographic characteristics. In the full sample, 1.2% of participants identified as gay or lesbian (1.6% of sexually active participants), 3.4% (4.7%) as bisexual, 2.2% (2.1%) as unsure, and 93.2% (91.6%) as heterosexual.

TABLE 1—

Distribution of Sexual Partners Within Sexual Orientation Identity Groups by Demographics Among Sexually Active Youths in 8 Jurisdictions Collecting Sexual Behavior and Identity Items: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, United States, 2005 and 2007

| Heterosexual (n = 24 427) |

Gay/Lesbian (n = 468) |

Bisexual (n = 1408) |

Unsure (n = 579) |

||||||||||

| Characteristics | Opposite, No. (%) | Same/Opposite, No. (%) | Same, No. (%) | Opposite, No. (%) | Same/Opposite, No. (%) | Same, No. (%) | Opposite, No. (%) | Same/Opposite, No. (%) | Same, No. (%) | Opposite, No. (%) | Same/Opposite, No. (%) | Same, No. (%) | Total, No. |

| All individuals | 23 456 (95.3) | 479 (2.3) | 492 (2.5) | 82 (18.5) | 143 (31.8) | 243 (49.7) | 507 (32.0) | 782 (58.8) | 119 (9.2) | 373 (59.6) | 179 (34.0) | 27 (6.4) | 26 882 |

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Boys | 12 682 (96.6) | 133 (1.1) | 243 (2.3) | 57 (21.6) | 71 (24.5) | 135 (53.9) | 95 (29.5) | 177 (53.5) | 58 (17.0) | 182 (60.5) | 71 (28.6) | 18 (10.9) | 13 922 |

| Girls | 10 774 (93.7) | 346 (3.6) | 249 (2.6) | 25 (14.2) | 72 (41.6) | 108 (44.2) | 412 (32.7) | 605 (60.3) | 61 (7.0) | 191 (58.6) | 108 (39.4) | 9 (2.0) | 12 960 |

| Age, y | |||||||||||||

| 13–14 | 2252 (94.7) | 42 (2.4) | 50 (2.9) | 9 (26.2) | 12 (12.9) | 18 (61.0) | 51 (31.9) | 92 (57.4) | 20 (10.7) | 46 (61.0) | 20 (29.9) | 7 (9.0) | 2619 |

| 15–16 | 11 407 (95.1) | 227 (2.4) | 241 (2.6) | 42 (25.9) | 60 (30.7) | 110 (43.5) | 275 (30.0) | 407 (58.7) | 69 (11.3) | 168 (57.0) | 94 (35.9) | 11 (7.1) | 13 111 |

| 17–18 | 9797 (95.6) | 210 (2.1) | 201 (2.2) | 31 (9.3) | 71 (35.8) | 115 (54.9) | 181 (35.0) | 283 (59.3) | 30 (5.7) | 159 (62.9) | 65 (32.3) | 9 (4.9) | 11 152 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||||||

| Black | 4972 (96.0) | 67 (0.9) | 141 (3.1) | 23 (28.2) | 34 (34.9) | 56 (36.9) | 70 (29.2) | 145 (59.4) | 21 (11.3) | 73 (63.0) | 38 (28.2) | 9 (8.8) | 5649 |

| Hispanic | 5766 (95.7) | 117 (2.2) | 142 (2.0) | 28 (21.4) | 37 (30.1) | 72 (48.4) | 120 (35.1) | 228 (55.8) | 37 (9.1) | 99 (63.9) | 42 (31.3) | 6 (4.8) | 6694 |

| Asian | 697 (94.3) | 21 (2.3) | 26 (3.4) | …a | 7 (18.9) | 6 (75.2) | 17 (47.8) | 21 (42.0) | 7 (10.2) | 28 (73.3) | 9 (14.0) | … a | 847 |

| Other | 1353 (92.4) | 40 (4.1) | 44 (3.5) | 7 (6.5) | 19 (31.9) | 25 (61.6) | 47 (25.8) | 75 (67.2) | 9 (7.0) | 42 (65.3) | 24 (34.5) | … a | 1687 |

| White | 10 668 (94.8) | 234 (3.0) | 139 (2.2) | 19 (12.0) | 46 (31.4) | 84 (56.6) | 253 (31.4) | 313 (60.0) | 45 (8.6) | 131 (49.2) | 66 (45.7) | 7 (5.0) | 12 005 |

Note. Total unweighted sexually active n = 26 882. All numbers are unweighted whereas all percentages utilize adjusted sampling weights.

Cell sizes equal to and lower than 5. Students within these cells were still retained in the denominator of relevant percentages.

Among sexually active youths, most who engaged in exclusively same-sex behavior identified as heterosexual (64.5%) and a minority identified as gay or lesbian (21.4%). Conversely, the majority of youths who identified as gay or lesbian had a history of exclusively same-sex behavior (50.6%), followed by those who engaged in sexual activity with both sexes (30.0%). Among those who had sexual contact with both sexes, 49.5% identified as bisexual and 32.0% as heterosexual. The converse was also true; most youths who identified as bisexual had a history of sexual activity with both sexes (60.1%). Model 1 in Table 2 shows the associations between sexual behavior and identity from a logistic regression model that included main effects of race/ethnicity and sex. Youths who engaged in any same-sex behavior had higher odds of identifying as gay or lesbian or bisexual compared with those with only other sexual behavior.

TABLE 2—

Multilevel Logistic Regression Model of Associations Between Sexual Behavior and Identity, and the Interaction With Sex and Race/Ethnicity Among Sexually Active Youths in the 8 Jurisdictions Collecting Sexual Behavior and Identity Items: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, United States, 2005 and 2007

| Models | Gay or Lesbian Identity, OR (95% CI) | Bisexual Identity, OR (95% CI) | Unsure Identity, OR (95% CI) |

| Model 1: main effects–only model | |||

| Sexual behavior | |||

| Same-sex behavior | 95.67 (61.43, 149.02) | 6.95 (4.61, 10.48) | 2.41 (1.27, 4.58) |

| Same- and opposite-sex behavior | 30.34 (18.64, 49.38) | 48.19 (38.22, 60.76) | 8.37 (5.97, 11.74) |

| Opposite-sex behavior (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Birth sex | |||

| Male | 1.44 (1.00, 2.06) | 0.38 (0.29, 0.49) | 1.13 (0.84, 1.53) |

| Female (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | 1.75 (1.10, 2.80) | 0.92 (0.68, 1.26) | 1.01 (0.68, 1.50) |

| Hispanic | 1.75 (1.12, 2.73) | 1.03 (0.77, 1.37) | 0.82 (0.54, 1.24) |

| Asian | 0.54 (0.12, 2.22) | 0.62 (0.29, 1.34) | 3.03 (1.68, 5.47) |

| Other | 1.62 (0.74, 3.54) | 0.94 (0.52, 1.71) | 2.23 (1.28, 3.89) |

| White (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Model 2: interactions model with sex and sexual behavior | |||

| Same-sex behavior × male | 1.59 (0.66, 3.80) | 3.60 (1.57, 8.25) | 7.57 (1.21, 47.43) |

| Same- and opposite-sex behavior × male | 2.28 (0.89, 5.88) | 3.20 (1.81, 5.68) | 2.69 (1.36, 5.32) |

| Opposite-sex behavior × female (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Model 3: interactions model with race/ethnicity and sexual behavior | |||

| Same-sex behavior × Black | 0.14 (0.05, 0.43) | 0.77 (0.26, 2.24) | 0.34 (0.06, 2.03) |

| Same- and opposite-sex behavior × Black | 0.41 (0.13, 1.29) | 2.36 (1.26, 4.43) | 0.76 (0.32, 1.78) |

| Same-sex behavior × Hispanic | 0.27 (0.09, 0.79) | 1.00 (0.46, 2.19) | 0.39 (0.09, 1.82) |

| Same- and opposite-sex behavior × Hispanic | 0.38 (0.12, 1.21) | 1.15 (0.68, 1.96) | 0.71 (0.32, 1.60) |

| Same-sex behavior × Asian | 0.12 (0.00, 3.49) | 0.46 (0.02, 10.54) | 0.94 (0.14, 6.31) |

| Same- and opposite-sex behavior × Asian | 0.42 (0.02, 11.71) | 0.86 (0.19, 3.93) | 0.35 (0.08, 1.58) |

| Same-sex behavior × other race/ethnicity | 0.50 (0.07, 3.57) | 0.37 (0.07, 1.92) | 0.02 (0.00, 4.13) |

| Same- and opposite-sex behavior × other race/ethnicity | 0.44 (0.04, 5.04) | 0.78 (0.26, 2.29) | 0.20 (0.04, 0.92) |

| Opposite-sex behavior × White (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Interaction models accounted for main effects of sexual behavior and either sex or race/ethnicity.

Sex Differences

As shown in model 1 of Table 2, boys were significantly more likely than girls to identify as gay or lesbian and less likely to identify as bisexual. Model 2 in Table 2 shows associations between sexual behavior and identity from a logistic regression model that included main effects for sex and interactions between sex and behavior. There were no significant differences in associations between gay or lesbian identity and sexual behavior on the basis of sex. Interactions were significant for bisexual identity; girls always had higher rates of bisexual identity, but boys showed a stronger association between identity and behavior. This association among boys was true for the higher odds of identifying as bisexual with same-sex–only and both-sex contact.

Youths who had sexual contact with both sexes had higher odds of reporting being unsure of their sexual identity. In this multivariable model there was no main effect of sex on being unsure of identity and in the absence of any same-sex contact, boys and girls had similar odds of identifying as unsure. However, if same-sex contact occurred, boys were significantly more likely than girls to say they were unsure of their identity.

Racial/Ethnic Differences

As shown in model 1 of Table 2, sexually active Black and Hispanic youths were significantly more likely to identify as gay or lesbian than were White youths. Asian youths were significantly less likely to identify as bisexual. Both Asian and “other” youths were significantly more likely than Whites to identify as unsure.

Model 3 in Table 2 shows the results of a logistic regression model with identity as the dependent variable and independent variables including racial/ethnic group and interactions between racial/ethnic group and behavior. In terms of gay or lesbian identity, Black and Hispanic youths had a significantly smaller association between identity and behavior than did White youths, meaning they had less concordance for these 2 dimensions of sexual orientation. In terms of bisexual identity, Black youths showed the opposite pattern than for gay or lesbian identity; they showed a significantly stronger association between behavior and bisexual identity than did White youths. For unsure identity, “other” race/ethnicity youths who had both-sex contact showed less of an association with unsure identity than did White youths.

Developmental Patterns

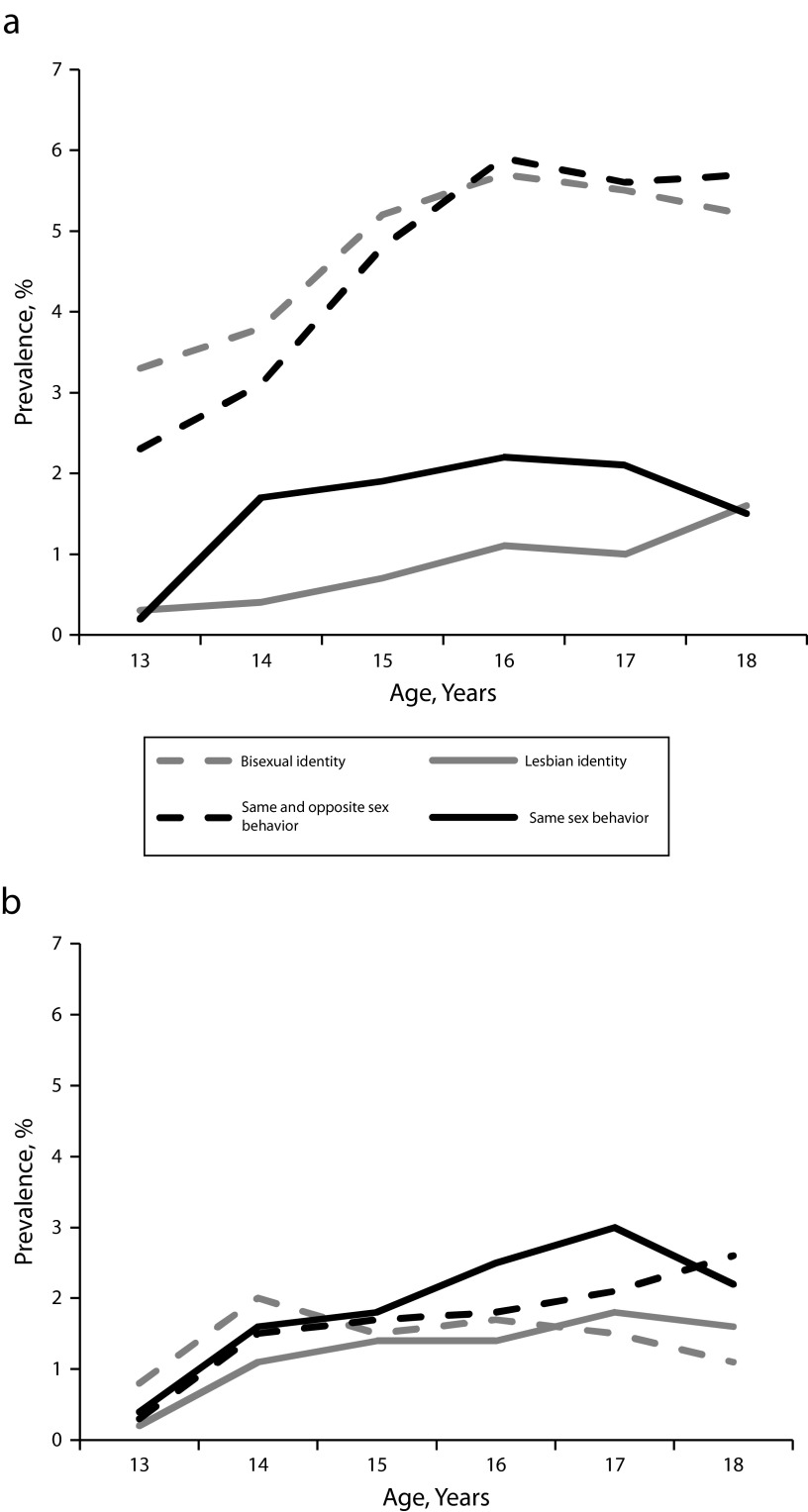

With our cross-sectional data, Figure 1a illustrates the prevalence of minority identities and sexual behavior across ages among all girls (sexually active and non–sexually active). There was an increase in the prevalence of bisexual identity (odds ratio [OR] = 1.21; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.08, 1.37) and behavior (OR = 1.33; 95% CI = 1.17, 1.51) from ages 13 to 16 years, which then remained around 5% to 6% at ages 17 to 18 years. Lesbian identity (OR = 1.61; 95% CI = 1.19, 2.18) also increased in prevalence across development; however, same-sex behavior (OR = 1.18; 95% CI = 0.97, 1.43) did not reach significance. Higher prevalences of lesbian and bisexual identities with increasing age accompanied approximately equal declines in heterosexual and unsure identities (data not shown). Higher prevalences of same-sex contact with age came from fewer abstinent girls by age, as opposite-sex contact also increased in frequency with age.

FIGURE 1—

Prevalence of sexual minority identity and behavior by age among youths in the 8 jurisdictions collecting sexual behavior and identity items for (a) girls and (b) boys: Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2005 and 2007.

Note. Data are cross-sectional prevalence estimates at each age.

Among boys, there was a different pattern (Figure 1b). There was no significant increase in the prevalence by age of bisexual identity or behavior. However, gay identity (OR = 1.47; 95% CI = 1.12, 1.92) and exclusively same-sex behavior (OR = 1.54; 95% CI = 1.24, 1.90) did show significant increases in prevalence in early adolescence. Unlike girls, the higher prevalence by age of gay identity was accompanied only by a lower prevalence of unsure identity, not by a decline in heterosexual identity. Similar to girls, the higher prevalence of same-sex behavior was accompanied by a lower prevalence of abstinence. Unlike girls, who had the highest prevalence of bisexual behavior and identity at age 18 years, among boys it was the behavioral dimensions (same-sex and both-sex) that had the highest prevalence at age 18 years (e.g., 2.2% and 2.6% for behavior vs 1.6% and 1.1% for identity).

Sexually Abstinent Youths

Table 3 shows the distribution of sexual orientation identities for abstinent youths (41.6% of sample). Abstinence was more common among those with a heterosexual or unsure identity than among gay or lesbian– and bisexual-identified youths (χ2(3) = 223.47; P < .001).

TABLE 3—

Number and Percentage (Relative to Total Sample) of Sexually Abstinent Youths by Sexual Orientation Identity Groups and Demographics in 8 Jurisdictions Collecting Sexual Behavior and Identity Items: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System, United States, 2005 and 2007

| Demographics | Heterosexual, No. (%),χ2, or OR (95% CI) | Gay or Lesbian, No. (%), χ2, or OR (95% CI) | Bisexual, No. (%), χ2, or OR (95% CI) | Unsure, No. (%), χ2, or OR (95% CI) | Total Abstinent, No. |

| All abstinent | 23 580 (42.5) | 116 (22.3) | 418 (19.7) | 621 (44.8) | 24 735 |

| Sex | 191.78* | 1.09 | 0.11 | 3.89* | |

| Boys | 10 679 (38.6) | 64 (26.2) | 100 (22.2) | 254 (41.9) | 11097 |

| Girls | 12 901 (46.5) | 52 (16.3) | 318 (19.0) | 367 (47.5) | 13 638 |

| Age, y | 0.68* (0.66, 0.69) | 0.87 (0.68, 1.11) | 0.74* (0.64, 0.86) | 0.81* (0.71, 0.93) | |

| 13–14 | 6739 (62.7) | 21 (36.0) | 111 (28.8) | 199 (59.6) | 7070 |

| 15–16 | 11 867 (45.0) | 54 (24.1) | 220 (20.5) | 284 (48.3) | 12 425 |

| 17–18 | 4974 (30.8) | 41 (17.7) | 87 (15.4) | 138 (33.8) | 5240 |

| Race/ethnicity | 896.82* | 3.34 | 6.46 | 12.27* | |

| Black | 2662 (33.5) | 28 (33.1) | 44 (14.7) | 64 (33.2) | 2798 |

| Hispanic | 3693 (39.2) | 17 (10.7) | 97 (22.3) | 94 (41.9) | 3901 |

| Asian | 1740 (70.1) | …a | 20 (27.0) | 64 (62.6) | 1827 |

| Other | 1170 (41.7) | 12 (25.5) | 19 (13.2) | 48 (46.3) | 1249 |

| White | 14315 (44.8) | 56 (20.3) | 238 (20.7) | 351 (48.8) | 14 960 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Effects for age represent the change in odds for each year of age. All numbers are unweighted whereas all percentages utilize adjusted sampling weights.

Cell size equal to or lower than 5.

*P < .05.

The prevalence of abstinence declined by age group in these cross-sectional data, but it did so more among heterosexual youths (OR = 0.68; 95% CI = 0.66, 0.69) than among unsure youths (OR = 0.81; 95% CI = 0.71, 0.93). Among bisexuals there was also a negative association with age (OR = 0.74; 95% CI = 0.64, 0.86), but the association was not significant among gay or lesbian youths. Among heterosexual youths, there were large differences in the frequency of abstinence by race/ethnicity, but there were no significant differences in abstinence among gay or lesbian or bisexual youths.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we focused on dimensions of sexual identity and behavior among a probability sample of high-school youths in the United States. We investigated the degree of association between these dimensions and examined variations in the dimensions by sex and race/ethnicity. Incongruence between sexual identity and behavior for the sexual-minority youths was apparent; most youths who engaged in exclusively same-sex behavior identified as heterosexual and only a minority identified as gay or lesbian. These results illustrate that no single item will identify most sexual-minority youths and, as suggested by others,11,13,25 studies should consider assessing multiple dimensions of sexual orientation (behavior, identity, sexual and romantic attractions). When this is not feasible because of strict limits on the number of items, it is best to select the dimension most germane to the topic of study (e.g., behavior for studies of HIV transmission). It remains unclear which dimensions are most associated with some health domains (e.g., mental health).

Consistent with other studies,13,29,37 many of the sexually active gay or lesbian youths reported sexual activity with the opposite sex. This is unsurprising because these youths may do so as a way of confirming a lack of other-sex desire, because of sincere opposite-sex attractions, because of peer pressure or desire for conformity, or as part of their identity exploration process. Of the bisexual youths, nearly 60% reported sexual activity with both sexes, with nearly another third reporting sexual activity only with the opposite sex. However, among sexually active heterosexual youths, only 4.7% reported sexual activity with the same or both sexes. The National Survey of Family Growth found similar low levels of same-sex behavior among heterosexually identified young people.37

We suggest that these results indicate that heterosexuality is foreclosed—meaning it is not confirmed by experimenting with the same sex. A high degree of congruence among components of sexual orientation is expected for heterosexual individuals, but less so for gay, lesbian, or bisexual individuals, in light of their normative experimentation. Finally, nearly two thirds of youths who identified as unsure reported sexual contact only with the opposite sex. The sexual behavior of these youths may suggest, as has been found,28 that these youths will eventually identify as heterosexual.

Sex Differences

Our observed sex differences are consistent with those previously reported in the literature. We found that among sexually active youths, 12.8% of girls and 6.8% of boys reported having sexual contact with the same or both sexes, a sex difference that has been found by others.37 Girls were more likely than boys to identify as bisexual, in keeping with findings from others.19

When gay or lesbian and bisexual identities are combined into 1 sexual-minority identity, more girls than boys are sexual minorities.27 Indeed, we found that among sexually active youths, twice as many girls as boys (9.1% vs 3.7%) identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual. We found no sex difference in the association between same-sex behavior and gay or lesbian identity, but boys showed a stronger association between same-sex behavior and bisexual identity. This suggests that girls may be more likely than boys to rely on factors other than sexual behavior, such as romantic affections or social consideration,38 when adopting bisexual identity labels.

Racial/Ethnic Differences

Asians, for whom little is known in the literature regarding sexual orientation, were more likely than White youths to indicate being unsure of their sexual orientation. If longitudinal, prospective data on predominantly White youths generalize to Asian youths,32 the unsure Asians will eventually identify as heterosexual.

The data indicated that Black youths were more likely than White youths to identify as gay or lesbian, a pattern that had been noted in the National Survey of Family Growth, although only among boys.30 We found novel differences by race/ethnicity in the association between sexual identity and behavior. For gay or lesbian identities, Black youths had a smaller association than White youths with same-sex behavior, but for bisexual identity Black youths had a larger association with behavior. Latino youths showed the same pattern as Black youths in terms of a smaller association between same-sex behavior and adoption of a gay or lesbian identity label, compared with White youths.

To understand these effects it would be useful to explore in future research if the culturally bound conceptualization and definitions of “gay/lesbian” and “bisexual” labels are the same across racial/ethnic groups. Differences in the definitions of these labels could explain the patterns found in this study. It is also possible that racial/ethnic–minority youths experience more social pressure against identifying as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, and so their sexual behavior is less linked to their identity. This is consistent with research suggesting later sexual minority identity integration among racial/ethnic minority youths.30

Developmental Patterns

In our cross-sectional study, the prevalence of sexual-minority identity and behavior at each age varied by sex. Two distinct patterns were apparent for girls: the bisexual and lesbian patterns. Among girls, the prevalence of bisexuality increased at early and middle adolescence before reaching an inflection point. The lesbian pattern was more consistent by age in prevalence of identity and behavior. For boys, a reverse pattern was apparent; there was an increase in the prevalence of gay identity and behavior in early and middle adolescence, but a relatively consistent prevalence throughout adolescence for bisexual identity and behavior. An important limitation of these data is their cross-sectional nature, only allowing the estimate of prevalence at each age, rather than developmental trajectories.

Comparable findings are rare, but they suggest that additional study is needed to assess developmental patterns, preferably with longitudinal data. Data from The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health),17 spanning 3 longitudinal waves and mean ages of youths from 15.8 to 21.7 years, found a behavioral pattern similar to our own among girls: an increasing prevalence of bisexual behavior. Add Health found a constant prevalence of only same-sex behavior over time whereas we found a trend toward increased prevalence. For boys, increasing prevalence of behavior with both sexes or only with the same sex over time was apparent. Another study involving 4 waves of data, with youths spanning ages 12 through 25 years over time, found that sexual identity was relatively consistent for exclusively heterosexual and homosexual boys and girls.32 As in the previous study, some bisexual youths were consistent in their identity over time, but many others changed and change occurred equally for boys and girls.

Abstinent and Unsure Youths

Abstinence was elevated among heterosexual and unsure youths compared with lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. This is unsurprising for 2 reasons. First, the unsure youths will likely assume a heterosexual identity at some later time,27 implying an underlying similarity between the 2 groups. However, it may be that the “similarity” is a methodological artifact, attributed to youths who do not understand the questions being asked of them and, thus, check “unsure.”15

Second, becoming aware of a developing same-sex sexuality in the context of a society that continues to stigmatize homosexuality means that some sexual-minority youths are likely to test their attractions by having sexual relations with the other sex followed by, when the attractions do not abate, sexual relations with the same sex.29 Therefore, sexual-minority youths are less likely to be abstinent than are heterosexual youths, especially at younger ages.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that there is little congruence between identity and behavior markers of sexual orientation among US adolescents and, importantly, that these associations differ by sex and race/ethnicity. We encourage researchers to consider the implications of different markers of sexual orientation for whatever health outcomes are examined. For example, a study using a representative sample of adolescents in Norway found that the sexual behavior dimension, rather than attractions or identity, was the most important correlate of suicide attempts.39 Unfortunately, we were not able to consider sexual attractions, because of the paucity of such data in the YRBS, a limitation we hope will be addressed in future surveys. We also hope that more cities and states query their youths about sexual orientation, given the known health disparities by sexual orientation.1 Despite these limitations, the value of the YRBS, as evident here and in other articles in this special issue, is clear for understanding sexual orientation and its role in health-related concerns.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under award R21HD051178 and by the IMPACT LGBT Health and Development Program at Northwestern University. B. Mustanski is supported by a William T. Grant Scholars Award.

Assistance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Division of Adolescent and School Health and the work of the state and local health and education departments who conduct the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) made the project possible. We would like to thank Aimee Van Wagenen for her role compiling the pooled data set.

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the CDC, the William T. Grant Foundation, or any of the agencies involved in collecting the data.

Human Participant Protection

Protocol approval was not necessary because we obtained de-identified data from secondary sources. Data use agreements were obtained from Vermont Department of Health and the Rhode Island Department of Health, which were the only 2 departments of health that required these agreements for access to YRBSS data.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Almeida J, Johnson R, Corliss H, Molnar B, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: the influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38(7):1001–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birkett M, Espelage D, Koenig B. LGB and questioning students in schools: the moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. J Youth Adolesc. 2009;38(7):989–1000. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9389-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bontempo DE, D’Augelli AR. Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths’ health risk behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(5):364–374. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Wissow LS, Woods ER, Goodman E. Sexual orientation and risk of suicide attempts among a representative sample of youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(5):487–493. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang Y, Perry DK, Hesser JE. Adolescent suicide and health risk behaviors: Rhode Island’s 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(5):551–555. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell ST, Joyner K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: evidence from a national study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1276–1281. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saewyc EM, Hynds P, Skay CL et al. Suicidal ideation and attempts in North American school-based surveys: are bisexual youth at increasing risk? J LGBT Health Res. 2007;3(2):25–36. doi: 10.1300/J463v03n02_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mustanski BS, Garofalo R, Emerson EM. Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2426–2432. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauer GR, Jairam JA. Are lesbians really women who have sex with women (WSW)? Methodological concerns in measuring sexual orientation in health research. Women Health. 2008;48(4):383–408. doi: 10.1080/03630240802575120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mustanski B, Kuper L, Greene GJ. Development of sexual orientation and identity. In: Tolman DL, Diamond LM, editors. Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW. Theories and etiologies of sexual orientation. In: Tolman DL, Diamond LM, editors. Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Igartua K, Thombs BD, Burgos G, Montoro R. Concordance and discrepancy in sexual identity, attraction, and behavior among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(6):602–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Savin-Williams RC. Who’s gay? Does it matter? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15(1):40–44. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saewyc EM, Bauer GR, Skay CL, et al. Measuring sexual orientation in adolescent health surveys: evaluation of eight school-based surveys. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(4):345.e1–345.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dill BT, Zambrana RE. Emerging Intersections: Race, Class, and Gender in Theory, Policy, and Practice. New: Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gattis MN, Sacco P, Cunningham-Williams RM. Substance use and mental health disorders among heterosexual identified men and women who have same-sex partners or same-sex attraction: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(5):1185–1197. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9910-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeffries WL IV. Sociodemographic, sexual, and HIV and other sexually transmitted disease risk profiles of nonhomosexual-identified men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(6):1042–1045. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savin-Williams RC, Diamond LM. Sexual identity trajectories among sexual-minority youths: gender comparisons. Arch Sex Behav. 2000;29(6):607–627. doi: 10.1023/a:1002058505138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL. Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36(3):385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu F, Sternberg MR, Markowitz LE. Men who have sex with men in the United States: demographic and behavioral characteristics and prevalence of HIV and HSV-2 infection: results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2006. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(6):399–405. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181ce122b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu F, Sternberg MR, Markowitz LE. Women who have sex with women in the United States: prevalence, sexual behavior and prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection-results from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2006. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(7):407–413. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181db2e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baumeister RF. Gender differences in erotic plasticity: the female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychol Bull. 2000;126(3):347–374. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diamond LM. Female bisexuality from adolescence to adulthood: results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(1):5–14. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savin-Williams RC, Joyner K, Rieger G. Prevalence and stability of self-reported sexual orientation identity during young adulthood. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(1):103–110. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9913-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Braun L. Sexual identity development among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: consistency and change over time. J Sex Res. 2006;43(1):46–58. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ott MQ, Corliss HL, Wypij D, Rosario M, Austin BS. Stability and change in self-reported sexual orientation identity in young people: application of mobility metrics. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(3):519–532. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9691-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grov C, Bimbi DS, Nanin JE, Parsons JT. Race, ethnicity, gender, and generational factors associated with the coming-out process among gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals. J Sex Res. 2006;43(2):115–121. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosario M, Meyey-Bahlburg HFL, Hunter J, Exner TM. The psychosexual development of urban lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. J Sex Res. 1996;33(2):113–126. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Ethnic/racial differences in the coming-out process of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: a comparison of sexual identity development over time. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2004;10(3):215–228. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dubé EM, Savin-Williams RC. Sexual identity development among ethnic sexual-minority male youths. Dev Psychol. 1999;35(6):1389–1398. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.6.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mustanski B, Newcomb M, Garofalo R. Mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: a developmental resiliency perspective. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2011;23(2):204–225. doi: 10.1080/10538720.2011.561474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manalansan MF. Double minorities: Latino, Black, and Asian men who have sex with men. In: Savin-Williams RC, editor. The Lives of Lesbians, Gays, and Bisexuals: Children to Adults. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace College Publishers; 1996. pp. 393–415. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Savin-Williams RC. Ethnic- and sexual-minority youth. In: Savin-Williams RC, editor. The Lives of Lesbians, Gays, and Bisexuals: Children to Adults. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace College Publishers; 1996. pp. 152–165. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mustanski B, Van Wagenen A, Birkett M, Eyster S, Corliss HL. Identifying sexual orientation health disparities in adolescents: analysis of pooled data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2005 and 2007. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):211–217. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brener ND, Kann L, Kinchen S et al. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53(RR-12):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCabe J, Brewster KL, Tillman KH. Patterns and correlates of same-sex sexual activity among US teenagers and young adults. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011;43(3):142–150. doi: 10.1363/4314211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diamond LM. The desire disorder in research on sexual orientation in women: contributions of dynamical systems theory. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(1):73–83. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9909-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wichstrøm L, Hegna K. Sexual orientation and suicide attempt: a longitudinal study of the general Norwegian adolescent population. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(1):144–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]