Abstract

Objective To examine whether the age based quality measure for screening for colorectal cancer is associated with overuse of screening in patients aged 70-75 in poor health and underuse in those aged over age 75 in good health.

Design Retrospective cohort study utilizing electronic data from the Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System, the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States.

Setting VA Health Care System.

Participants Veterans aged ≥50 due for repeat average risk colorectal cancer screening at a primary care visit in fiscal year 2010.

Main outcome measures Completion of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, or fecal occult blood testing within 24 months of the 2010 visit.

Results 399 067 veterans met inclusion/exclusion criteria (mean age 67, 97% men). Of these, 38% had electronically documented screening within 24 months. In multivariable log binomial regression adjusted for Charlson comorbidity index, sex, and number of primary care visits, screening decreased markedly after the age of 75 (the age cut off used by the quality measure) (adjusted relative risk 0.35, 95% confidence interval 0.30 to 0.40). A veteran who was aged 75 and unhealthy (in whom life expectancy might be limited and screening more likely to result in net burden or harm) was significantly more likely to undergo screening than a veteran aged 76 and healthy (unadjusted relative risk 1.64, 1.36 to 1.97).

Conclusions Specification of a quality measure can have important implications for clinical care. Future quality measures should focus on individual risk/benefit to ensure that patients who are likely to benefit from a service receive it (regardless of age), and that those who are likely to incur harm are spared unnecessary and costly care.

Introduction

Quality measures are metrics used to assess the quality of healthcare. The definitions, or specifications, for quality measures are commonly derived directly from clinical practice guidelines. One example is the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measure, which seeks to decrease underuse of screening for colorectal cancer in the United States. The current HEDIS measure is based on the screening recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guideline, which suggests routine screening in patients at average risk starting at the age of 50 and continuing through to the age of 75.1 The United Kingdom National Health Service (NHS) has proposed a similar age based measure for the bowel cancer screening program in the UK.2 Large integrated healthcare organizations in the US, such as the Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System, have also introduced age based quality measures as part of their accountability and improvement programs; indeed, VA has an active measurement and feedback system in place to encourage screening in age eligible individuals.3

Despite the use of these well established age based quality measures, experts recommend that the decision to screen be informed by estimated life expectancy rather than age alone.4 5 Age is a reliable proxy for life expectancy in young patients (long life expectancy) and very elderly patients (short life expectancy). But in most elderly patients eligible for screening, life expectancy varies considerably according not only to age but also health status. For instance, a 74 year old man who is in excellent health has a life expectancy of almost 15 years.4 Evidence suggests that screening for colorectal cancer is likely to be of benefit in such a patient and should therefore be encouraged.6 On the other hand, a 74 year old man who is in poor health has a life expectancy of less than five years.4 Evidence suggests that screening by any method is unlikely to be of benefit and might even be harmful in such a patient and should therefore be discouraged.6 7 In fact, the American College of Physicians (ACP) guideline for screening for colorectal cancer specifically recommends that screening should not be performed in individuals with a life expectancy of less than 10 years.5 Yet, as operationalized, the quality measure for screening for colorectal cancer encourages screening equally for both healthy and frail patients aged 74, potentially leading to overuse. Conversely, the specification of a maximum age beyond which performance of screening is not “counted” could promote underuse in healthy patients who are older than 75 but are still likely to benefit because of good life expectancy.8 9 As highlighted by Walter and colleagues in 2004, such an approach fails to sufficiently consider “who received the test, why it was performed, or whether the patient wanted it.”10

We examined whether the upper age cut off of the quality measure for colorectal cancer screening is associated with overuse of screening among patients aged 70-75 in poor health and underuse in those aged over 75 in good health. We used data from the VA Health Care System, the largest integrated healthcare system in the US. Specifically, we compared screening between two groups of patients: older individuals who were within the target age range in the quality measure (aged 70-75) and older individuals who were beyond the age where screening “counts” toward the quality measure (age >75). We hypothesized that patients who were within the target age range but were in poor health (low likelihood of benefit from screening and potential for net harm) would be more likely to undergo screening than patients who were beyond the target age range but were in good health (higher likelihood of benefit from screening). We sought to examine how quality measures that utilize “one size fits all” targets without specific regard to individual risk and benefit influence both appropriate and inappropriate use of care.

Methods

VA Health Care System

We performed a retrospective cohort study using electronic data from the VA Health Care System. This system serves nearly nine million veterans (that is, people who previously served in the US military) across over 150 medical centers and nearly 1400 community based outpatient clinics. Though VA is under a single centralized leadership, its organizational structure allows for substantial regional and local autonomy in terms of budgetary decisions and approaches to delivery of care. The healthcare system has a robust centrally controlled quality measurement program, with a wide array of quality measures across various healthcare conditions.3 In parallel, medical centers have adopted computerized reminders that prompt providers to fulfill quality measures for services such as screening for colorectal cancer. Audits of performance are also reported to providers at many medical centers, further encouraging screening. Partly as a result of such approaches, VA is considered a leader in the delivery of high quality care in the US.11

VA physicians are salaried, but a small percentage of their full compensation comes in the form of “performance pay,” which can reward physicians for productivity, performance on quality metrics such as screening for colorectal cancer, or other locally determined factors. Many older veterans are eligible for Medicare insurance, which covers non-VA outpatient care. Thus, a considerable proportion of veterans receive care through both VA and private physicians.12 Although guidelines suggest that screening is not universally required in older patients, neither VA, Medicare, nor other private insurers currently limit coverage of screening for colorectal cancer in older adults in the US.

Study design and dataset

VA electronic data are available from fiscal year 2000 to the present time, including data on demographics, utilization of primary care and screening for colorectal cancer, and comorbidity status. We identified veterans who were regular users of VA primary care and preventive care and were due for repeat screening in the fiscal year 2010 (allowing for sufficient time to determine whether screening was subsequently utilized). Patients were included if they met the following criteria: primary care visit in 2010 when the patient was due for repeat colorectal cancer screening (age ≥50, no fecal occult blood test (FOBT) in the 12 months before the 2010 visit, no sigmoidoscopy in the five years before the 2010 visit, and no colonoscopy in the 10 years before the 2010 visit); and at least one additional primary care visit in the 12-24 months before the 2010 visit (to focus on patients who regularly use VA primary care). A similar approach has been used in other studies to identify regular users of VA primary care.13

To identify individuals who underwent screening for colorectal cancer through VA, we chose to focus on individuals who had undergone a previous fecal occult blood test with negative results in the 12-24 months before the 2010 visit. We made this decision on the basis of pilot work at a single VA medical center where we had access to more detailed clinical data, which showed that many veterans who seemed to be due for screening based on VA electronic data had in fact undergone previous colonoscopy screening outside VA (that is, VA electronic data are insensitive for detecting historical exposure to colonoscopy). Inclusion of these patients who were not due for screening in our cohort would lead to substantial underestimation of screening utilization. We carried out a sensitivity analysis to examine the impact of this inclusion criterion related to fecal occult blood testing on our results.

Fecal occult blood tests were identified by using Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC), and sigmoidoscopies and colonoscopies were identified by using ICD-9 (international classification of disease, ninth revision), Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), and Level II Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes (appendix table A). Patients were excluded if CPT or ICD-9 codes showed any of the following diagnoses between 2000 and the qualifying 2010 visit (appendix table B): previous colectomy; history of colon polyps; history of colorectal cancer; history of inflammatory bowel disease; or family history of colorectal cancer. These exclusion criteria were selected to ensure that the cohort comprised individuals who were at average (rather than increased) risk for colorectal cancer.

Outcome and predictor variables

We determined whether any screening test (fecal occult blood test, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy) was completed within 24 months after the qualifying 2010 visit (primary outcome variable). A 24 month follow-up window has been used in previous work on this topic as it allows patients ample time to schedule and complete a screening test.14 Secondary outcome variables included fecal occult blood test, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy performed within 24 months specifically for screening (that is, tests that were potentially performed for diagnostic purposes were excluded); fecal occult blood test within 24 months; sigmoidoscopy within 24 months; and colonoscopy within 24 months. To identify screening sigmoidoscopies and colonoscopies, we utilized an algorithm previously developed by Fisher and colleagues, using VA administrative data.15 To identify screening fecal occult blood tests, we excluded patients in whom ICD-9 codes showed a diagnosis of anemia or bleeding in the three months before the fecal occult blood test (indicating that it might have been performed for diagnostic purposes) (appendix table B).

Data were also extracted on several predictor variables, including demographic characteristics (age and sex), number of primary care visits in 2010, and health status. Race was not utilized as a covariate as it has been shown to have limited reliability in VA data.16

Health status was measured with the Deyo adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity index,17 based on inpatient and outpatient codes from the 24 months before and including the qualifying visit in 2010. The Charlson comorbidity index is a weighted score of 17 common comorbid conditions. Originally developed as a predictor of one year mortality after hospital discharge,18 subsequent work has shown that it can also be used as a predictor of long term mortality.19 In our study, the index was categorized according to the approach used by Walter and colleagues, in studies of screening in veterans (Charlson index 0, 1-3, or ≥4).7 14 In a 75 year old man, a Charlson index of 0 indicates good health, with an estimated life expectancy over 10 years.7 19 An individual with a Charlson index of 0 might have mild comorbid conditions, such as uncomplicated hypertension or osteoarthritis, which do not substantially affect life expectancy. Such patients are likely to benefit from screening for colorectal cancer.6 20. On the other extreme, a 75 year old man with a Charlson index ≥4 has poor health, with an estimated life expectancy of less than five years.7 19 A patient with a Charlson index ≥4 is likely to have multiple comorbid conditions that impact life expectancy, such as diabetes with end organ damage, congestive heart failure, and emphysema. Such patients are unlikely to benefit from (and might even be harmed by) screening.6 7 20

Statistical analysis

Screening completion rates were stratified by age at the time of the qualifying 2010 visit (50-69, 70-75, or >75), sex, Charlson comorbidity index, and number of primary care visits in 2010. We grouped 70-75 year olds together because previous research suggests that for individuals in this age range with a high burden of comorbidity life expectancy is similar and is less than the 10 years needed for benefit from screening.4 7 20 21 We carried out multivariable log binomial regression to identify independent predictors of screening utilization within 24 months of the qualifying 2010 visit and to calculate adjusted screening rates. Robust standard errors were used to adjust for clustering within facility. We also performed sensitivity analyses using our secondary outcome variables and broadening our inclusion criteria to include patients both with and without previous fecal occult blood testing. Analyses were performed with the Stata 12 statistical package (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The proportion of patients with missing data was negligible (date of birth was missing for 400 out of 4 756 477 patients). These 400 patients were excluded (appendix fig A).

Results

We identified 399 067 veterans who met our inclusion and exclusion criteria (table 1). The mean age was 67.2 (SD 9.7) years, and most were men. The median Charlson comorbidity index was 1 (interquartile range 1-3). Participants made a median of three visits to primary care clinics in fiscal year 2010.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in study of role of quality measurement in inappropriate use of screening for colorectal cancer. Figures are numbers (percentage) of patients (n=399 067)

| Characteristic | Participants | Age 50-69 | Age 70-75 | Age >75 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): | ||||

| 50-69 | 247 900 (62) | 247 900 | — | — |

| 70-75 | 53 351 (13) | — | 53 351 | — |

| >75 | 97 816 (25) | — | — | 97 816 |

| Men | 385 781 (97) | 236 832 (96) | 52 499 (98) | 96 450 (99) |

| Women | 13 286 (3) | 11 068 (4) | 852 (2) | 1366 (1) |

| Charlson comorbidity index: | ||||

| 0 | 127 968 (32) | 89 259 (36) | 14 621 (27) | 24 088 (25) |

| 1-3 | 213 814 (54) | 129 210 (52) | 29 916 (56) | 54 688 (56) |

| ≥4 | 57 285 (14) | 29 431 (12) | 8814 (17) | 19 040 (19) |

| Primary care visits in 2010: | ||||

| 1 | 49 191 (12) | 28 086 (11) | 6968 (13) | 14 137 (14) |

| 2 | 88 099 (22) | 51 686 (21) | 12 561 (24) | 23 852 (24) |

| 3 | 75 115 (19) | 46 694 (19) | 10 351 (19) | 18 070 (18) |

| ≥4 | 186 662 (47) | 121 434 (49) | 23 471 (44) | 41 757 (43) |

| Screening utilization*: | ||||

| Colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, or FOBT | 151 850 (38) | 113 835 (46) | 22 757 (43) | 15 258 (16) |

| Colonoscopy | 37 237 (9) | 31 430 (13) | 3549 (7) | 2258 (2) |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 2008 (1) | 1614 (1) | 201 (0.5) | 193 (0.2) |

| FOBT | 129 103 (32) | 94 725 (38) | 20 806 (39) | 13 572 (14) |

FOBT=fecal occult blood test.

*Categories are not mutually exclusive.

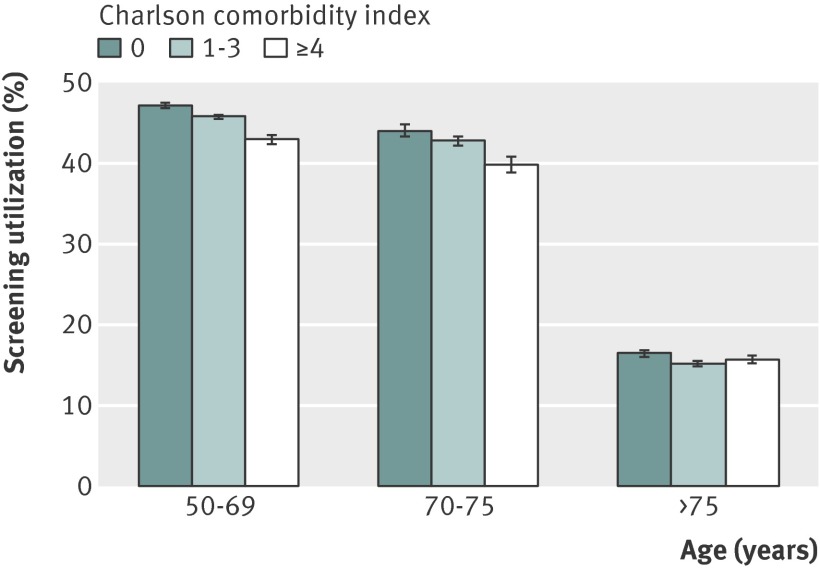

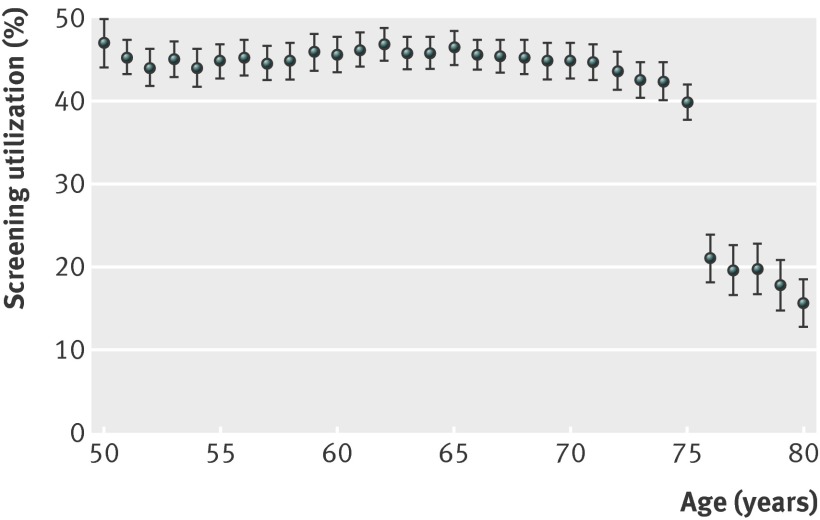

About 38% (151 850/399 067) of identified veterans (age ≥50 with no upper age cut off) underwent a screening test for colorectal cancer (fecal occult blood test, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy) in the 24 months after their qualifying 2010 primary care clinic visit (table 1). Screening was more common among younger and healthier veterans (and among those with a greater number of visits to a primary care clinic) (table 2). Screening was relatively stable from age 50 to age 75, but utilization declined abruptly after 75, matching the age cut off promoted by the existing VA quality measure (table 2 and figs 1-2 ). This finding was independent of comorbidity status, number of primary care visits, and demographic characteristics (fig 3 ). Of 53 346 veterans aged 70-75, 16.5% (8814/53 346) had a Charlson comorbidity index ≥4 (indicating poor health and shortened life expectancy). Though these veterans were unlikely to benefit from screening, 40% (3516/8814) underwent a screening test within 24 months. On the other hand, of 97 786 veterans aged >75, 24.6% (24 088/97 786) had a Charlson comorbidity of 0 (indicating excellent health and good life expectancy). Though many of these veterans would likely benefit from screening, only 16.5% (3964/24 088) underwent a screening test within 24 months. In fact, a veteran who was aged 75 and unhealthy (Charlson index ≥4) was significantly more likely to undergo screening than a veteran who was aged 76 and healthy (Charlson index 0) (unadjusted relative risk 1.64, 95% confidence interval 1.36 to 1.97; fig 2 ).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted* relative risks† and rates of screening for colorectal cancer by age and health status (n=399 067)

| Predictor variable | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR (95% CI) | Screening rate, % (95% CI) | RR (95% CI) | Screening rate, % (95% CI) | ||

| Age (years): | |||||

| 50-69 | 1 (reference) | 45.9 (45.7 to 46.1) | 1 (reference) | 45.6 (43.7 to 47.4) | |

| 70-75 | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95) | 42.7 (42.2 to 43.1) | 0.94 (0.92 to 0.96) | 42.9 (40.9 to 44.9) | |

| >75 | 0.34 (0.30 to 0.39) | 15.6 (15.4 to 15.8) | 0.35 (0.30 to 0.40) | 15.8 (13.6 to 18.1) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index‡: | |||||

| 0 | 1 (reference) | 41.0 (40.7 to 41.3) | 1 (reference) | 38.7 (36.8 to 40.5) | |

| 1-3 | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.93) | 37.5 (37.3 to 37.7) | 0.94 (0.93 to 0.95) | 36.0 (34.2 to 37.7) | |

| ≥4 | 0.82 (0.80 to 0.83) | 33.4 (33.0 to 33.8) | 0.87 (0.85 to 0.89) | 33.1 (31.6 to 34.6) | |

*Adjusted for sex and number of primary care visits in 2010; unadjusted results reflect simple proportions within each age or comorbidity group.

†P<0.001 for all comparisons.

‡In a 75 year old man, Charlson index of 0 indicates life expectancy >10 years, 1-3 indicates life expectancy 5-10 years, and ≥4 indicates life expectancy <5 years.

Fig 1 Relation between age, health status, and screening (n=399 067). In a 75 year old man, Charlson index of 0 indicates life expectancy >10 years, Charlson index of 1-3 indicates life expectancy of 5-10 years, and Charlson index ≥4 indicates life expectancy <5 years

Fig 2 Screening at age 75 v age 76 (n=21 499)

Fig 3 Screening by age (n=399 067) adjusted for sex, Charlson comorbidity index, and number of primary care visits in 2010

We performed several additional analyses to determine whether our inclusion and exclusion criteria (which were designed to identify regular users of VA primary care who seemed to be receiving colorectal cancer screening in VA) and primary outcome variable (any fecal occult blood test, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy within 24 months of the qualifying 2010 visit) might have resulted in spurious associations between characteristics of the quality measure and screening utilization. First, we repeated our analysis for all veterans with regular use of VA primary care irrespective of prior fecal occult blood testing. Second, we repeated our analysis using secondary outcome variables, including any fecal occult blood testing within 24 months of the 2010 visit; any sigmoidoscopy within 24 months; any colonoscopy within 24 months; and fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy within 24 months for screening purposes only (that is, diagnostic fecal occult blood tests, sigmoidoscopies, and colonoscopies were excluded). These sensitivity analyses showed similar results to our primary analysis, with an abrupt decrease in screening in veterans after age 75 independent of Charlson comorbidity index and number of primary care visits (appendix tables C and D).

Discussion

Principal findings and comparison with other studies

Quality improvement efforts that incorporate quality measures have been shown to be effective in promoting utilization of appropriate care.22 But as our work and that of others has shown, quality measures also have the potential to encourage utilization of inappropriate care.10 13 23 24 This is particularly true of measures that use a “one size fits all” or “treat to target” approach that is designed to encourage adherence to clinical practice guidelines (like the measure for screening for colorectal cancer).10 As our study suggests, such an approach can unintentionally discourage thoughtful clinical decision making. Fisher and colleagues found similar results in a 2005 study of veterans, reporting that quality improvement efforts to increase screening for colorectal cancer were accompanied by high rates of inappropriate use of screening fecal occult blood tests.25 Work in other clinical domains also supports our results. For example, Kerr and colleagues recently reported that high facility level performance on “treat to target” quality measures for veterans with diabetes was associated with overtreatment of both hypertension and hyperlipidemia.13 23 Efforts such as the Too Much Medicine and Choosing Wisely campaigns have sought to limit overuse by encouraging patients and providers to discuss the appropriateness of care when the value of a service might be low.26 But a patient and provider cannot have a meaningful discussion about whether to utilize a clinical service if they do not fully understand the value of care for that individual patient, nor if the provider is incentivized to order the service regardless of a patient’s characteristics or preferences. Thus, refining quality measures to be more individualized and sensitive to preferences is critical if we want to promote care that is both more appropriate and patient centered.27 A patient centered approach to quality measurement, one that incorporates health status and individual preferences, is particularly needed in older patients in whom age alone is an inadequate proxy for life expectancy (such as those aged 70-80). This need will only grow as the population ages (yielding increasing numbers of healthy and unhealthy older patients) and as quality improvement initiatives that incorporate quality measures are more widely adopted. Recent work by Cho and colleagues has shown that use of administrative data to estimate life expectancy can be further tailored not only by health status but also by race and sex.21 Such an approach could be utilized by healthcare systems to better target screening to those individuals who are more likely to benefit.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths and limitations. First and foremost, we utilized data from the largest integrated healthcare system in the US and analyzed data on nearly 400 000 patients. Furthermore, the use of VA data allowed us to examine the impact of a longstanding, comprehensive, and highly effective implementation of quality measures on both underuse and overuse. Because performance of screening for colorectal cancer among patients aged 50-75 is now a standard measure in many healthcare systems, it is likely that similar patterns of underuse and overuse can be found in other high performing healthcare systems.28 The use of VA data also presents some limitations. Specifically, because veterans might undergo procedures outside VA, our data probably underestimate true screening rates. Indeed, previous work that utilized abstraction of medical records to assess receipt of screening for colorectal cancer has shown that about 80% of VA patients aged 50-75 are up to date for screening.29 We sought to resolve this limitation in our primary analysis by including only veterans who had undergone previous fecal occult blood test screening in VA, but even these veterans might undergo subsequent screening outside VA. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that veterans aged 75 differ substantially from those who are 76 in terms of use of screening outside VA (fig 2 ). It is also important to note that our study is retrospective in design, and the observed results could, at least partly, be caused by unmeasured confounding. For instance, we could not adjust for some variables that are known to impact screening utilization, such as socioeconomic status, race, and education, though these factors are also not likely to vary substantially among veterans aged 75 versus 76. Additionally, electronic data are subject to imprecision in coding, which could result in both overestimation or underestimation of screening utilization.

Conclusions and policy implications

Our study suggests that the way quality measures are specified can have a profound effect on screening utilization. In the case of colorectal cancer screening, the translation of the US Preventive Services Task Force guideline into a quality measure has resulted in high adherence to guideline recommendations. But screening does not seem to be utilized according to expected benefit across the population. Specifically, screening is likely being overused in sick patients aged 75 and younger and underused in healthy patients aged over 75. Of note, both the task force guideline and the VA Clinical Preventive Services Guidance Statement encourage an individualized approach to screening for colorectal cancer in patients aged 76-85, but this nuance had not explicitly been incorporated into the quality measure. In the past year, however, VA has modified the quality measure specifications to permit exceptions for veterans age ≤75 with shortened life expectancies or serious comorbid medical conditions. Though this is an important first step towards a more individualized approach, future patient centered quality measures will need to incorporate more explicit measures of clinical benefit and ultimately help guide clinical decision making. In this way, we can ensure that patients who are likely to benefit from a service receive it (regardless of age) and those who might incur more harm than benefit are spared unnecessary and costly tests and treatments.

What is already known on this topic

Screening for colorectal cancer is an evidence based widely recommended preventive service that has traditionally been underused

Efforts to increase screening through quality measurement have been successful, and such efforts are now being implemented widely in the US and the UK

The implementation of “one size fits all” age based measures might have unintended effects on screening

What this study adds

In the largest integrated healthcare system in the US, age based measures for screening for colorectal cancer (which encourage screening in patients aged 50-75) promoted overuse of screening in unhealthy older patients and underuse in healthy older patients

Future quality measures should focus on clinical benefit rather than simply chronological age to ensure that patients who are likely to benefit from a service receive it (regardless of age), and that those who are likely to incur harm are spared unnecessary and costly care

We thank the following individuals for their valuable input on earlier drafts of this manuscript: Joseph Francis (VA Clinical Analytics and Reporting); Linda Kinsinger and Kathleen Pittman (VA National Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention); Jason A Dominitz, (VA Puget Sound Health Care System and the University of Washington School of Medicine); and Deborah Fisher (Durham VA Center for Health Services Research in Primary Care and Duke University Medical Center).

Contributors: SDS was involved in all aspects of this study, including study conception, study design, data analysis, and manuscript writing and revisions. EAK and SV contributed to study design and manuscript writing and revisions. SM contributed to study design, data analysis, and manuscript writing and revisions. AAP and PS contributed to manuscript revisions. SDS is guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by the Veterans Health Administration. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or final approval of the manuscript. The opinions expressed in this paper are of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: SDS had financial support from the Department of Veterans Affairs for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System (RO: 2011-100615) on 28 March 2012.

Transparency: SDS affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained. All authors had full access to study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Data sharing: Statistical code is available on request from the corresponding author.

Cite this as: BMJ 2014;348:g1247

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix: Supplementary tables A-D and flow chart (fig A)

References

- 1.Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2008;149:627-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHS Information Centre. Extension of NHS bowel cancer screening programme to men and women aged up to 75. Secondary extension of NHS bowel cancer screening programme to men and women aged up to 75. https://mqi.ic.nhs.uk/IndicatorDefaultView.aspx?ref=1.05.08.

- 3.Kerr EA, Fleming B. Making performance indicators work: experiences of US Veterans Health Administration. BMJ 2007;335:971-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA 2001;285:2750-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Hopkins RH Jr, Humphrey LL, Levine J, Sweet DE, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: a guidance statement from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:378-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross CP, Soulos PR, Ross JS, Cramer LD, Guerrero C, Tinetti ME, et al. Assessing the impact of screening colonoscopy on mortality in the Medicare population. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:1441-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kistler CE, Kirby KA, Lee D, Casadei MA, Walter LC. Long-term outcomes following positive fecal occult blood test tesults in older adults: benefits and burdens. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1344-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zauber AG, van Ballegooijen M, Petitti D, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I. United States Preventive Services Task Force recommendations: age to end screening misunderstood. Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shellnut JK, Wasvary HJ, Grodsky MB, Boura JA, Priest SG. Evaluating the age distribution of patients with colorectal cancer: are the United States Preventative Services Task Force guidelines for colorectal cancer screening appropriate? Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:5-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter LC, Davidowitz NP, Heineken PA, Covinsky KE. Pitfalls of converting practice guidelines into quality measures: lessons learned from a VA performance measure. JAMA 2004;291:2466-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keyhani S, Ross JS, Hebert P, Dellenbaugh C, Penrod JD, Siu AL. Use of preventive care by elderly male veterans receiving care through the Veterans Health Administration, Medicare fee-for-service, and Medicare HMO plans. Am J Public Health 2007;97:2179-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petersen LA, Byrne MM, Daw CN, Hasche J, Reis B, Pietz K. Relationship between clinical conditions and use of Veterans Affairs health care among Medicare-enrolled veterans. Health Serv Res 2010;45:762-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beard AJ, Hofer TP, Downs JR, Lucatorto M, Klamerus ML, Holleman R, et al. Assessing appropriateness of lipid management among patients with diabetes mellitus: moving from target to treatment. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:66-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walter LC, Lindquist K, Nugent S, Schult T, Lee SJ, Casadei MA, et al. Impact of age and comorbidity on colorectal cancer screening among older veterans. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:465-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher DA, Grubber JM, Castor JM, Coffman CJ. Ascertainment of colonoscopy indication using administrative data. Dig Dis Sci 2010;55:1721-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sohn MW, Zhang H, Arnold N, Stroupe K, Taylor BC, Wilt TJ, et al. Transition to the new race/ethnicity data collection standards in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Popul Health Metr 2006;4:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:1245-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SJ, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Conell-Price J, O’Brien S, Walter LC. Time lag to benefit after screening for breast and colorectal cancer: meta-analysis of survival data from the United States, Sweden, United Kingdom, and Denmark. BMJ 2013;346:e8441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho H, Klabunde CN, Yabroff KR, Wang Z, Meekins A, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, et al. Comorbidity-adjusted life expectancy: a new tool to inform recommendations for optimal screening strategies. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:667-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asch SM, McGlynn EA, Hogan MM, Hayward RA, Shekelle P, Rubenstein L, et al. Comparison of quality of care for patients in the Veterans Health Administration and patients in a national sample. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:938-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerr EA, Lucatorto MA, Holleman R, Hogan MM, Klamerus ML, Hofer TP, et al. Monitoring performance for blood pressure management among patients with diabetes mellitus: too much of a good thing? Arch Intern Med 2012:172:938-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Powell AA, White KM, Partin MR, Halek K, Christianson JB, Neil B, et al. Unintended consequences of implementing a national performance measurement system into local practice. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:405-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher DA, Judd L, Sanford NS. Inappropriate colorectal cancer screening: findings and implications. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:2526-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA 2012;307:1801-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerr EA, Hayward RA. Patient-centered performance management: enhancing value for patients and health care systems. JAMA 2013;310:137-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheffield KM, Han Y, Kuo YF, Riall TS, Goodwin JS. Potentially inappropriate screening colonoscopy in Medicare patients: variation by physician and geographic region. JAMA Intern Med 2013:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Long MD, Lance T, Robertson D, Kahwati L, Kinsinger L, Fisher DA. Colorectal cancer testing in the national Veterans Health Administration. Dig Dis Sci 2012;57:288-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix: Supplementary tables A-D and flow chart (fig A)