Abstract

Cell types, both healthy and diseased, can be classified by inventories of their cell-surface markers. Programmable analysis of multiple markers would enable clinicians to develop a comprehensive disease profile, leading to more accurate diagnosis and intervention. As a first step to accomplish this, we have designed a DNA-based device, called “Nano-Claw”. Combining the special structure-switching properties of DNA aptamers with toehold-mediated strand displacement reactions, this claw is capable of performing autonomous logic-based analysis of multiple cancer cell-surface markers and, in response, producing a diagnostic signal and/or targeted photodynamic therapy. We anticipate that this design can be widely applied in facilitating basic biomedical research, accurate disease diagnosis and effective therapy.

At the boundaries of eukaryotic cells, different cell-surface receptors, together with other proteins, lipids and carbohydrates, function in cascade and participate in the communication between the cell and the outside world. However, in cancer cells, alterations in the expression level and/or function of the cell membrane receptors can lead to systemic dysfunction, such as aberrant cellular metabolism, signaling and proliferation.1,2 In recent decades, advances in biomedicine have expanded our knowledge of the molecular signatures of diseases. By profiling the high or low expression levels of multiple membrane markers, medical practitioners will more precisely target diseased cells and provide more accurate disease therapy.

Most identified cell-surface markers are not exclusively expressed on the target population of diseased cells. A marker over-expressed in cancer cells is often also expressed at a lower level in some normal cells. In diseases such as leukemia, both healthy and diseased subpopulations of white blood cells display surface markers that are indistinguishable by the current single-receptor antibody therapy, potentially leading to serious complications and even death by the indiscriminate invasion of the host defense system.3 In comparison, a more practical and less risk-prone approach would simultaneously assess multiple surface receptors to pinpoint specific disease cells and enhance diagnostic accuracy in differentiating similar cells.4,5

Some AND-gate-based bireceptor-targeting methods have been recently demonstrated, including the utilization of a proximity-based ligation probe,6 bispecific antibodies,7 chimeric costimulatory antigen receptors8 and a logic-gated DNA origami robot.9 However, considering the large population of similar cells in biological systems, a reliable approach capable of examining more complex cellular configurations is still needed. With this goal in mind, we have designed a self-assembled DNA computation device, which can screen multiple cell-surface receptors (inputs) and autonomously integrate the screening results into logic operations, such as a diagnostic signal and/or a therapeutic effect (outputs).

Mainly due to its predictable Watson-Crick hybridization and immense information-encoding capacity, DNA has been widely used to construct devices performing intelligent tasks, such as sensing10 and computation.9,11-17 Among these, aptamers are DNA/RNA strands that are able to selectively recognize a wide range of targets, from small organic/inorganic molecules to proteins.18-21 Recently, a panel of aptamers has been selected for cell membrane proteins using a process called cell-SELEX.22 These aptamers demonstrate the ability to identify different expression patterns of the membrane receptors in a variety of cell types.18 Since they are capable of DNA hybridization, aptamers can be integral components of a logic sensor for cell identification. Our goal is to use aptamers as building blocks for a molecularly assembled logic robot, called the “Nano-Claw”, which can recognize the expression levels of multiple cell membrane markers.

Structurally, this logic robot consists of an oligonucleotide backbone as the scaffold,23,24 several structure-switchable aptamers as “capture toes”, and a logic-gated DNA duplex as the “effector toe” (Figure 1). The “capture toes” have two functions: first targeting each cell-surface marker, and then generating the respective barcode oligonucleotide for activation of the “effector toe”. Finally, the “effector toe” analyzes these barcode oligonucleotides, and autonomously makes decisions in generating a diagnostic signal (such as fluorescence) and therapeutic effect.

Figure 1.

The symbols and construction schemes are shown for (a) 2-input trivalent “Y”-shaped Nano-Claw and (b) 3-input tetravalent “X”-shaped Nano-Claw. (c) Flow cytometry experiment to determine the best cDNA sequences with a high Cy5.5 fluorescence signal (from biotin-labeled TC01, Sgc4f or Sgc8c aptamer) and low FITC fluorescence signal (labeled on the candidate strands).

The functions of the “capture toes” were achieved on the basis of structure-switchable aptamers.25,26 In the absence of target, the aptamer binds to a piece of complementary DNA (cDNA) to form a duplex structure. However, when a target is introduced, the structures are induced to switch from aptamer/cDNA duplex to aptamer/target complex and release the cDNA as an output.10,25 Three aptamers, Sgc8c, Sgc4f and TC01, were chosen to respectively target three overexpressed markers (PTK7 for Sgc8c; Sgc4f and TC01 targets not yet identified) on the surface of cancer cells, such as human acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells (CCRF-CEM). Several 11-19 nt-long candidate strands were tested for each ap-tamer, and three 15 nt-long cDNA strands were chosen: cS15 for Sgc8c aptamer, cF15 for Sgc4f aptamer and cT15 for TC01 ap-tamer. These cDNA strands strongly bound with their respective aptamer in the absence of target (Figure S1). Furthermore, they did not prohibit the binding of the aptamers to their corresponding cellular targets (a strong Cy5.5 fluorescence signal in flow cytometry experiment) and could be freed after cellular binding (a weak FAM fluorescence signal) (Figure 1c).

Based on these aptamer/cDNA conjugates, two simple logic gate operations were first tested to prove the computational functions. The first is an AND logic gate [input (1, 1), output 1], which simultaneously identifies the presence of two markers on the same cell surface (Figure 2a). Using Sgc8c and Sgc4f aptamers as an example, a FAM dye-labeled cS15 strand is first displaced from the Sgc8c/cS15-FAM conjugate by an input target (PTK7 on the cell surface). This cS15-FAM then serves as an input for a downstream gate to form the Sgc4f-S15/cS15-FAM conjugate, where the S15-tagged Sgc4f strand has been rationally designed to bring the cS15-FAM reporter back to the cell membrane and provide a signal. As shown in Figure 2d, ON signaling from this Boolean AND logic gate (output 1) is possible only if both sets of aptamer-targeting markers are present on the cell surface (e.g., CCRF-CEM cells); conversely, OFF signaling (output 0) is observed in the absence of either one of the markers (e.g., either human Burkitt's lymphoma cells, Ramos, or epitheloid cervical carcinoma cells, HeLa) or both receptors (e.g., human erythromyeloblastoid leukemia cells, K562).

Figure 2.

(a) Experimental scheme of aptamer-switch AND gate. (b) Adjusting the gating properties by changing the DNA sequence design, CEM and HeLa cells can be either dually targeted or distinguished. (c) Cell viability test for the AND and INH gates after visible irradiation for 3h and subsequent growth for 48h (*: p-value < 0.05; **: p-value <0.001; by comparison with each irradiated cell type only, n=3). (d,e) Flow cytometric analysis and confocal microscope images (TAMRA dye) of the fluorescence signal with/without the gate probes for the AND and INH gate. The fluorescence values and their error bars (mean ± s.d.) were calculated from three experiments.

Since membrane markers are found in different concentrations on different cell surfaces, the ideal logic device should also have the capacity to recognize and report based on different expression levels. For this purpose, a thresholding function can be introduced into the DNA-based gates. For example, in the above-mentioned AND logic gate, the cDNA strand could be synthesized with different sequence lengths to fine-tune aptamer-cell interactions (Figure S2). Specifically, a longer cS strand (e.g., cS19 compared with cS15 or cS11) requires a larger number of PTK7 receptors on the cell surface to activate the gate's signal. Such a thresholding property allows targeting of different surface receptor patterns, which are otherwise difficult to sense, because of the various expression levels of membrane markers. As an example, the Sgc8c+++/Sgc4f+ HeLa cell and Sgc8c++/Sgc4f++ CEM cell could be either dually targeted or distinguished through rational design of the cS sequence (Figure 2b and S2).

The second logic gate is an INH-gate, whose output is exclusively activated in the presence of only one specific input. In other words, the gate switch is ON (output, 1) only in the absence of input A and the presence of input B, or “B AND-NOT A”. In a single test, this gate is capable of mapping the underexpression of one receptor (input A) and the overexpression of another (input B) on the cell surface. The underexpressed target functions as a safeguard against treating normal cells, which may also exhibit cancer markers at some level [input (1, 1)]. To engineer the INH gate, we simply modified the above-mentioned AND gate by adding a NOT gate that implements logical negation. Instead of the direct fluorophore labeling on the cS15 probe, here nonlabeled cS15 functions as an inhibitor to block the binding event between an additional cS15-FAM and Sgc4f-S15 (NOT gate, Figure S3). Hence, the presence of input Sgc8c-binding marker (PTK7) has the power to disable the entire system, so that only the Ramos cells could be targeted [input (0, 1)] (Figure 2e and Figure S4).

To prove that the targeted therapeutic effect can be triggered by these structure-switchable aptamer conjugates, a porphyrin-based photosensitizer, chlorine e6 (Ce6), was employed to induce photodynamic therapy (PDT), i.e., the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon light irradiation.27,28 Because of the limited therapeutic window (the travelling distance of ROS), specific localization of the photosensitizer at the diseased site is required for efficient PDT. To test this triggering response, we incorporated Ce6 into the reporter probes (Figure S5), and cell viability was determined by propidium iodide (PI) staining after incubation with the aptamer-based logic gate complex and Ce6-receptor probe. As shown in Figure 2c, in both AND and INH-gated systems, efficient specific photoinduced therapy was achieved for target cancer cells.

Using the “A AND B” gate as an example, one potential limit of the current system stems from the condition of neighboring cells expressing receptor A or B, thus leading to a fake joint positive signal to confound the results. Based on our preliminary cell mixture experimental results, however, this effect is prevented in part by the high local concentration of released strands near the cell where the targeting aptamer binds (Figure S6). As an effort to further avoid such fake positives, we designed and constructed a physically-conjugated DNA assembly, which combines the above-mentioned blueprint design of structure-switchable aptamers (“capture toes”) with the toehold-mediated strand displacement reaction (“effector toe”).

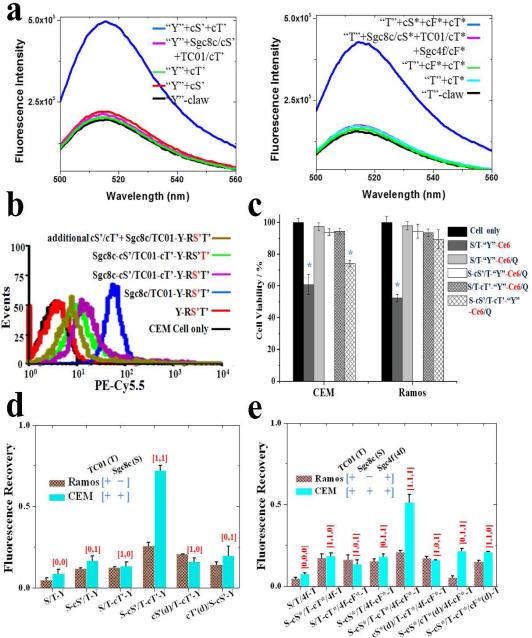

As illustrated in Figure 1a, a “Y”-shaped AND Nano-Claw was constructed from the self-assembly of an Sgc8c/cS’ duplex, a TC01/cT’ duplex (both as capture toes) and a R/S’/T’ complex (effector toe). The cS’ and cT’ strands were optimized from the above-mentioned cS15 and cT15 strands by an 8-base elongation to accommodate strand displacement reactions. In an individual DNA strand displacement reaction, a new oligonucleotide strand (e.g., R from R/S’) is revealed in response to the presence of some initiator strand (e.g., cS’), which recognizes a single-stranded domain, called the toehold. A cascade effect can be realized when many these reactions are linked, such that the newly revealed output strand of one reaction can initiate another strand displacement elsewhere.29-32 In this Nano-Claw structure, the cS’ and cT’ strands in the original aptamer/cDNA duplexes could be displaced by capturing their respective cell-surface receptors. Then, these displaced strands subsequently interact with the S’ and T’ strands in the effector toe, resulting in the cascade removal of both S’ and T’ gate strands. Finally, this results in a positive therapeutic effect.

After purification by gel electrophoresis (Figure S7), the dual-marker-targeting function of the AND-gated Nano-Claw was then verified. The logical targeting function was proved by incubating the claw with additional input cS’ and cT’ strands (Figure 3a and Figure S8). The gated fluorescence was activated only when both the cS’ and cT’ strands were present, proving an AND gate operation. As expected, the specific targeting properties of both Sgc8c and TC01 aptamers were still retained after the conjugation within the claw structure (Figure S9). More importantly, the introduction of cS’ and cT’ strands did not obviously influence the capture property of aptamers, and these cDNA strands could be successfully displaced on the targeted cell surface (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Fluorescence measurements in buffer solution and (b) flow cytometric signals prove the gating and displacement properties for the Nano-Claw, where the red-colored S’ or T’ indicates the dye-labeled strand. (c) Cell viability test for the “Y”-shaped claw, where “Q” stands for BHQ-3 quencher that prevented the Ce6-induced PDT reaction. (d,e) The signal reporting of the Nano-Claw on the CEM and Ramos cell membrane, “cX(d)” represents the fully-complementary control X/cX duplex that was labeled on one capture toe and could not release the cX strand.

Based on the measured cell surface fluorescence recovery efficiency (using the fluorescence from quencher-free Nano-Claw as the maximum signal), target CCRF-CEM cells (expressing both receptors) could be clearly distinguished from control Ramos cells (expressing only one of the two receptors) (Figure 3d). In several parallel control tests, it was also confirmed that the existence and targeted release of both types of cDNA strands were necessary for the success of the Nano-Claw operation (Figure S10). Simply by modifying the R strand with a Ce6 photosensitizer instead of the fluorophore, a targeted therapeutic effect could be triggered by the logic cell surface profiling of this Nano-Claw device (Figure 3c).

To further demonstrate the programmable power of our sensor, another “Sgc8c AND TC01 AND Sgc4f” Nano-Claw was designed to, in a single step, target cells co-expressing three different receptors (Figure 1b). Based on an “X”-shaped oligonucleo-tide molecular assembly, the cascaded displacement of three gate strands from the R/S*/F*/T* complex was realized through the targeted receptor-binding of all three “capture toes” (Figure 3d). It is noteworthy that the linker length for the “capture toes” plays a significant role in the operation of this AND-AND logic device, possibly due to the steric effects among different surface markers when Nano-Claw and corresponding targets migrate toward each other on the cell surface. (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The effect of the “poly-T” linker length on the functions of the (a) “Y”- or “X”-shaped claw with two capture toes and (b) “X”-shaped claw with three capture toes. The fluorescence values were calculated based on the distributions in the flow cytometer from three experiments.

An interesting study by Douglas et al. proved the basic concept of logic cell-targeting through a two-input AND-gated DNA origami barrel.9 In contrast, we are aiming here to develop a much simple device which can successfully perform more complex logic operations on targeted cancer cell surfaces. During the preparation of the manuscript, Rudchenko et al. reported another interesting DNA-based cascade system, which can step-wise distinguish cells by individually examining 2-or-3 different expressions of clusters of differentiation (CDs).33 In this study, we have designed another blueprint to accomplish a similar goal, but by uniquely taking advantage of the nucleic acid nature of the ap-tamer molecules. Compared to the always-ON probes proposed by Rudchenko et al, the spontaneous activating ability of our structure-switchable aptamers provides a real “autonomous” operation, i.e., without the need to remove unbound strands before the addition of activators and reporters. Thus, the entire process of input-binding/logic-analysis/output-generation can be realized within a single operation. Moreover, the conjugated claw structure guarantees the distributions and ratios among different receptor-targeting ligands on each individual cell surface, and the assembled DNA nanostructures have also been reported to increase the biostability of these nucleic acid tags.34,35

In summary, we have designed and engineered a simple, but powerful, DNA device that can be used to target diseased cell surfaces. Through Boolean operations, this device is capable of autonomously analyzing multiple cell molecular signature inputs and realizing targeted therapeutic effects. The programmable nature of nucleic acids makes it possible to further scale up and amplify the power of this Nano-Claw design, for example by covalently linking the aptamer probe with the displaceable strand (e.g., through polyethylene glycol linkers), or replacing the Ce6 with other reporting systems, drugs or nanoparticles. Meanwhile, some artificial nucleotides may be introduced to further enhance the biostability of the device in complex biological systems, such as serum. We anticipate these structure-switchable-aptamer-based devices can be employed to construct smart molecular robots for applications in basic research, biomedical engineering, and personalized medicine.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work is supported by the National Key Scientific Program of China (2011CB911000), NSFC grants (NSFC 21221003 and NSFC 21327009) and China National Instrumentation Program 2011YQ03012412, and by the National Institutes of Health (GM079359 and CA133086).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The DNA sequences, chemicals and reagents, cell lines, DNA synthesis, optimization of structure-switchable aptamers, AND-gate and INH-gate operation, and construction and characterizations of the Nano-Claw. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hollingsworth MA, Swanson BJ. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:45. doi: 10.1038/nrc1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Png KJ, Halberg N, Yoshida M, Tavazoie SF. Nature. 2012;481:190. doi: 10.1038/nature10661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikeda A, Shankar DB, Watanabe M, Tamanoi F, Moore TB, Sakamoto KM. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;88:216. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou H, Jiao P, Yang L, Li X, Yan B. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:680. doi: 10.1021/ja108527y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kluza E, van der Schaft DW, Hautvast PA, Mulder WJ, Mayo KH, Griffioen AW, Strijkers GJ, Nicolay K. Nano Lett. 2010;10:52. doi: 10.1021/nl902659g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Söderberg O, Gullberg M, Jarvius M, Ridderstråle K, Leuchowius KJ, Jarvius J, Wester K, Hydbring P, Bahram F, Larsson LG, Landegren U. Nat Methods. 2006;3:995. doi: 10.1038/nmeth947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmes D. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:798. doi: 10.1038/nrd3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kloss CC, Condomines M, Cartellieri M, Bachmann M, Sadelain M. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:71. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas SM, Bachelet I, Church GM. Science. 2012;335:831. doi: 10.1126/science.1214081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Cao Z, Lu Y. Chem Rev. 2009;109:1948. doi: 10.1021/cr030183i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie Z, Wroblewska L, Prochazka L, Weiss R, Benenson Y. Science. 2011;333:1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1205527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benenson Y, Gil B, Ben-Dor U, Adar R, Shapiro E. Nature. 2004;429:423. doi: 10.1038/nature02551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gil B, Kahan-Hanum M, Skirtenko N, Adar R, Shapiro E. Nano Lett. 2011;11:2989. doi: 10.1021/nl2015872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seelig G, Soloveichik D, Zhang DY, Winfree E. Science. 2006;314:1585. doi: 10.1126/science.1132493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pei R, Matamoros E, Liu M, Stefanovic D, Stojanovic MN. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5:773. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian L, Winfree E, Bruck J. Nature. 2011;475:368. doi: 10.1038/nature10262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elbaz J, Lioubashevski O, Wang F, Remacle F, Levine RD, Willner I. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5:417. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang X, Tan W. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:48. doi: 10.1021/ar900101s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Breaker RR. Nature. 2004;432:838. doi: 10.1038/nature03195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sefah K, Shangguan D, Xiong X, O'Donoghue MB, Tan W. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1169. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Famulok M, Hartig JS, Mayer G. Chem Rev. 2007;107:3715. doi: 10.1021/cr0306743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shangguan D, Li Y, Tang Z, Cao ZC, Chen HW, Mallikaratchy P, Sefah K, Yang CJ, Tan W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602615103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JB, Roh YH, Um SH, Funabashi H, Cheng W, Cha JJ, Kiatwuthinon P, Muller DA, Luo D. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:430. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan H, Park SH, Finkelstein G, Reif JH, LaBean TH. Science. 2003;301:1882. doi: 10.1126/science.1089389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nutiu R, Li Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4771. doi: 10.1021/ja028962o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang Z, Mallikaratchy P, Yang R, Kim Y, Zhu Z, Wang H, Tan W. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11268. doi: 10.1021/ja804119s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castano AP, Mroz P, Hamblin MR. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:535. doi: 10.1038/nrc1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han D, Zhu G, Wu C, Zhu Z, Chen T, Zhang X, Tan W. ACS Nano. 2013;7:2312. doi: 10.1021/nn305484p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang DY, Seelig G. Nat Chem. 2011;3:103. doi: 10.1038/nchem.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang DY, Winfree E. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:17303. doi: 10.1021/ja906987s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:263. doi: 10.1021/ja206690a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin P, Choi HM, Calvert CR, Pierce NA. Nature. 2008;451:318. doi: 10.1038/nature06451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudchenko M, Taylor S, Pallavi P, Dechkovskaia A, Khan S, Butler VP, Rudchenko S, Stojanovic MN. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:580. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mei Q, Wei X, Su F, Liu Y, Youngbull C, Johnson R, Lindsay S, Yan H, Meldrum D. Nano Lett. 2011;11:1477. doi: 10.1021/nl1040836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walsh AS, Yin H, Erben CM, Wood MJ, Turberfield AJ. ACS Nano. 2011;5:5427. doi: 10.1021/nn2005574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.