Abstract

Care coordination is an essential component of the pediatric health care home. This study investigated the attributes of relationship-based advanced practice registered nurse care coordination for children with medical complexity enrolled in a tertiary-hospital based health care home. Retrospective review of 2,628 care coordination episodes conducted by telehealth over a consecutive three-year time period for 27 children indicated parents initiated the majority of episodes and the most frequent reason was acute and chronic condition management. During this period, care coordination episodes tripled, with a significant increase (p<0.001) between years one and two. The increased episodes could explain previously reported reductions in hospitalizations for this group of children. Descriptive analysis of a program-specific survey showed parents valued having a single place to call and assistance managing their child’s complex needs. The advanced practice registered nurse care coordination model has potential for changing the health management processes for children with medical complexity.

Keywords: children with special health care needs, children with medical complexity, advanced practice registered nursing, health care home, care coordination

Children with special health care needs (CSHCN) have or are at risk for having chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions, and utilize more health and related services than the general population of children (McPherson et al., 1998). Approximately 15% of U.S. children are estimated to have special health care needs (National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs 2009/10, 2012). Within the population of CSHCN, there is a subgroup of children who have complex conditions involving numerous systems that require multiple service providers, and who rely intermittently or chronically on assistance from technology (E. Cohen et al., 2011). These children are defined by Cohen et al. (2011) as children with medical complexity (CMC) and represent a small yet important subgroup for focused interventions within the health care home.

The rise in health care expenditures for persons with complex and chronic health problems is placing a significant strain on the U.S. economy and health care system (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation & Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2010). CSHCN have health care expenditures three times higher than non-CSHCN (Newacheck & Kim, 2005) and significantly higher outpatient costs (Damiano, Momany, Tyler, Penziner, & Lobas, 2006). Analysis of provincial health plan data for a small subgroup of children meeting restrictive CMC criteria (single-organ or multiple-organ complex chronic conditions, neurologic impairment and/or requiring technology assistance) found 0.67% of children consumed a third of all health care dollars spent on children in the province (E. Cohen et al., 2012). On average, CMC saw 13 different physicians, had high 30-day readmission rates, and when technology assistance was required (e.g. tracheostomy, gastrostomy, cerebral-spinal-fluid shunt) CMC had significantly more physicians, readmissions and home health care visits (E. Cohen et al., 2012).

A greater life expectancy for CSHCN, including CMC, is attributed in part to advances in medicine and technology. (Tennant, Pearce, Bythell, & Rankin, 2010). Despite increasing numbers of CMC, a mismatch exists between the health needs of these children and the current health system (Wise, 2004). Finding efficient and productive ways to care for these children is an important ethical and economic issue. Coordinating care across the multiple providers and agencies is essential to stem the costs associated with caring for CMC (E. Cohen et al., 2012).

Coordination of care for all CSHCN, including CMC, is an essential component of the health care home model advocated by the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNAP, 2009) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (2005), and is identified as a national priority by the Institute of Medicine (2003). The pediatric health care home model of care promotes holistic care of children and their families by managing acute and chronic conditions through an ongoing relationship with a healthcare professional (NAPNAP, 2009). Care coordination in a pediatric health care home encompasses proactive and comprehensive health promotion for acute and chronic conditions, effective communication between health care home, family, other providers and community resources, and measurement and improvement of health and quality of life outcomes (McAllister, Presler, & Cooley, 2007). Research on the efficacy of coordinated, comprehensive care has shown a reduction in health care costs, an increase in family satisfaction and an improvement in clinical outcomes (Barry, Davis, Meara, & Halvorson, 2002; Liptak, Burns, Davidson, & McAnarney, 1998; Palfrey et al., 2004).

The intensity of care coordination needed by a child is dependent on the complexity of the child’s physical and psychosocial conditions (Kelly, Golnik, & Cady, 2008; Looman et al., 2013). The Value Model of nurse dose to patient complexity (Looman et al., 2013) illustrates the depth and breadth of knowledge, data synthesis, intervention complexity and interaction frequency required by populations with increasingly complex health needs. The advanced practice registered nurse (APRN), with autonomous scope of practice and specialized education, is ideally suited to provide high ‘nurse dose’ or high-intensity care coordination to CMC (Looman et al., 2013). The Value Model views care coordination for CMC as a relationship-based approach that assists complex problem solving with families rather than a task-oriented process supported by systems-level infrastructure such as care pathways or protocols (Looman et al., 2013). Health care teams that utilize APRNs to coordinate care for CMC have demonstrated improved outcomes and lower costs, particularly through a reduction in hospital length of stay (Cady, Finkelstein, & Kelly, 2009; Gordon et al., 2007).

Including APRN care coordination in the health management of CMC has shown improved outcomes, but a gap exists in understanding the type and frequency of interactions during care coordination episodes. Examining the attributes of APRN care coordination episodes is a critical first step in understanding how care coordination influences management of a child’s care at home and the overall health management of CMC. The purpose of this study was to investigate the telephone interactions of APRNs working in a tertiary hospital-based health care home and utilizing relationship-based care coordination for CMC.

Methods

Setting

The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective review. The U Special Kids (USK) program was established in 1996 at the University of Minnesota and linked to a tertiary center teaching hospital. USK team members included a .8 FTE pediatrician, two .8 FTE APRNs and a .5 FTE support person. The two APRNs provided high nurse-dose relationship-based care coordination to CMC living throughout the state of Minnesota. With the exception of annual clinic visits, all APRN interactions with the families of CMC were conducted exclusively by telephone, a low cost and readily available form of telehealth (Wyatt & Liu, 2002).

The USK program partnered with a child’s primary care provider (Kelly et al., 2008) to facilitate assessment and management of acute and chronic conditions, organize and disseminate critical health information, and coordinate health care, social service and community-based providers and services (Cady, Kelly, & Finkelstein, 2008). All care coordination was conducted by the two USK APRNs, who had three and five years of experience with the program at the start of the data collection time period. Each episode of care coordination was initiated by a telephone call and documented by the APRN. Typical clinical documentation included reason for initiating the care coordination episode, person(s) involved in the episode, the APRN’s assessment and plan of care, and the outcome of the episode. The mechanism of documentation evolved over time from a paper ‘call log’ typical of telephone triage programs to an electronic SOAP documentation (Weed, 1964) format (Word 2003, Microsoft, Redmond, WA) that was stored on a secured, dedicated server. The clinical care coordination documentation was stored separate from a child’s electronic medical record (EMR) because the EMR could not support this type of documentation.

Data Collection

The purpose of this study was to systematically describe and evaluate the content of telephone interactions as indicators of the process of relationship-based care coordination. Data for the retrospective review came from three sources: 1) in-person interviews with the two USK APRNs; 2) retrospective review of clinical care coordination documentation; and 3) data from a program-specific survey mailed to parents of children enrolled in the USK program. Data from all sources were collected by a masters-prepared research nurse working with the USK program.

Semi-structured interviews with the APRNs took place in the USK office prior to, during and after the retrospective review of records. The interviews focused on understanding care coordination documentation and workflow processes.

The retrospective review of clinical care coordination documentation encompassed a consecutive three-year time period. The starting point of the time period was one year after implementation of electronic care coordination documentation. During this three-year period, children enrolled and dis-enrolled from the USK program. Only children enrolled in the USK program for the entire data collection period (n=27) were included in the data collection sample.

Demographic data (gender, age and medical problem list) were abstracted from the electronic medical record for each child in the data collection sample. The USK pediatrician assigned one of six diagnostic categories based on the dominant presenting condition from the child’s problem list. The genetic syndrome/congenital anomaly category encompassed chromosomal abnormalities and developmental delays, but the unique co-morbidities of cerebral palsy resulted in a separate diagnostic category for this condition. The neurodegenerative category included seizure and muscle atrophy disorders, and the other conditions category encompassed mental health disorders, cancer and conditions caused by accident. The remaining two categories consisted of immunodeficiency and gastrointestinal disorders. To facilitate standardized data collection during the retrospective record review, categories for coding ‘initiating reason’ and ‘initiating person’ for each care coordination episode were defined using Antonelli & Antonelli’s (Antonelli & Antonelli, 2004) care coordination data collection tool. Content validity was established during semi-structured interviews with the USK APRNs. Concurrent validity was established by the research nurse coding the first five care coordination episodes for two children not included in the data collection sample, and comparing the results to coding by the USK pediatrician. All telehealth care coordination episodes documented by the APRNs for children enrolled during the three-year time period were manually reviewed by the research nurse. A single initiating reason and initiating person for each episode was coded using the pre-defined and validated data collection categories (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of all Care Coordination Episodes over a 3 year period for 27 Children

| Characteristic | # | % |

|---|---|---|

| Reason for Initiating Episode | ||

| Parental Follow-up, Education and Support | 330 | 13% |

| Acute and Chronic Condition Management | 1252 | 48% |

| Care Coordination with Providers | 490 | 19% |

| Care Coordination with Community Resources | 259 | 10% |

| Scheduling | 244 | 9% |

| Inpatient Communication/Discharge Planning | 53 | 2% |

| Total | 2628 | 100% |

| Person Initiating Episode | ||

| Parent/Family | 1764 | 67% |

| Nurse | 398 | 15% |

| MD Office | 163 | 6% |

| Pharmacist | 114 | 4% |

| Insurance | 14 | 1% |

| School | 63 | 2% |

| Social Services | 37 | 1% |

| PCA | 27 | 1% |

| Other | 48 | 2% |

| Total | 2628 | 100% |

Note. Data represent care coordination episodes for 27 children continuously enrolled in the USK program over 36 months. “Episode” refers to a single encounter involving the APRN and a parent or service provider. Subcategories under Reasons for Initiating and Person Initiating were coded as mutually exclusive for data collection.

A program-specific survey was distributed to all families of children enrolled in the USK program (n=32) during the third year of the data collection period. The survey was developed internally by the USK staff for program evaluation purposes and psychometric evaluation was not conducted. Results of this survey are reported for descriptive purposes only. This sample included the families of children involved in the retrospective care coordination episode review (n=27). Seventeen program-specific questions with a 4 point Likert response assessed parental perception of care coordination and the impact of the USK program on health service use.

Data Analysis

Descriptive and statistical data analysis of the coded care coordination episode data and the parent survey data used Intercooled Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Paired t-test checked for differences in the number of care coordination episodes across the three-year time period.

Results

The children (n=27) included in this retrospective review were enrolled in the USK program during the entire three-year time period. The gender distribution was 52% female, 48% male and the average age at start of the data collection period was 7 years. The most common diagnostic category was genetic syndrome/congenital anomaly (48%), followed by other conditions (15%), cerebral palsy (11%), neurodegenerative disease (11%), immunodeficiency (11%) and gastrointestinal (4%).

Over the three-year time period, 2,628 telehealth care coordination episodes were electronically documented by the two USK APRNs for the 27 children in the data collection sample. The mean and median number of episodes per child over the three-year period was 32 and 24. Half of the episodes were initiated for acute and chronic condition management and two-thirds of the episodes were initiated by parents (Table 1).

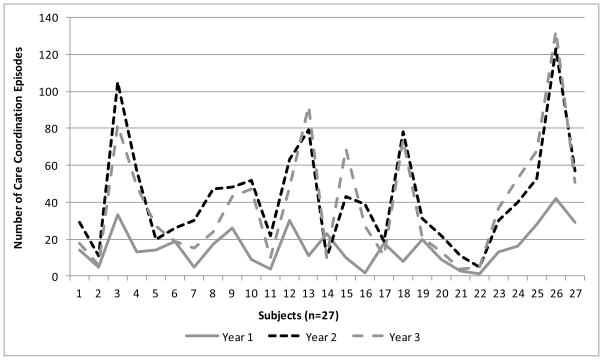

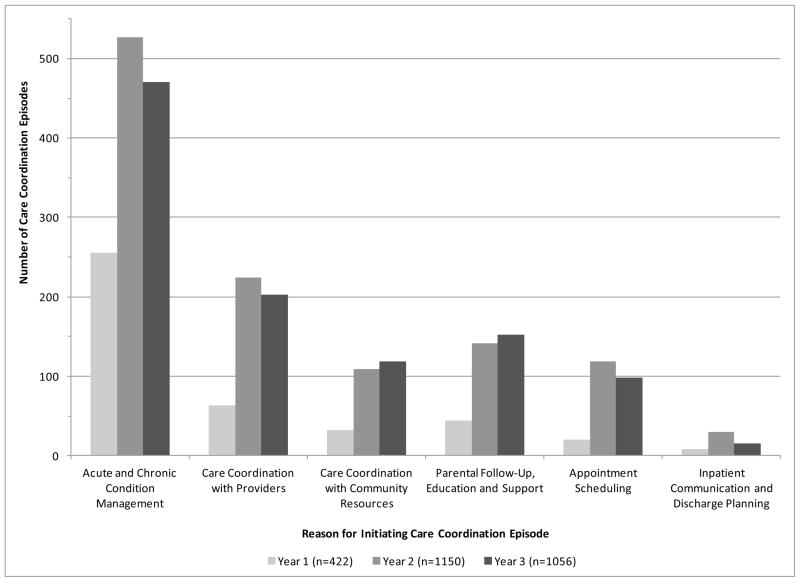

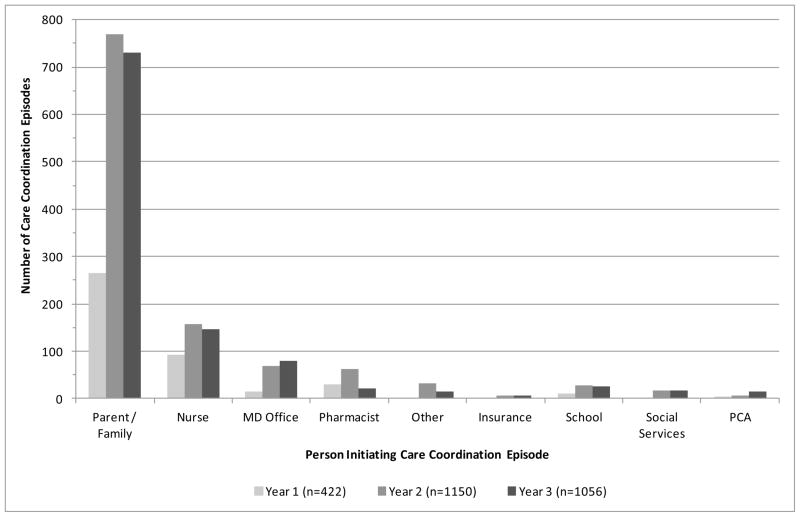

At the start of the data collection time period, the average number of years enrolled in the USK program was 1.5. Nine children were in their first year of enrollment, seven children were in their second year, five children were in their third year and six children were enrolled for four or more years. The number of care coordination episodes conducted for each subject during each data collection year appears in Figure 1. A statistically significant increase in the frequency of a subject’s care coordination episodes (p<.001) between year one and year two was found. The distribution of care coordination episodes across initiating reason and initiating person appear in Figures 2 and 3. Interviews with the APRNs focused on exploring the content of care coordination episodes. APRNs noted that while many calls were initiated by parents for management of acute and chronic conditions, the focus of the call included parental education to identify subtle changes in their child’s condition. Follow-up calls with these parents then focused on relationship-based, collaborative management and monitoring of the child’s condition through telehealth. Interviews with the APRNs also revealed that episodes for acute and chronic condition management typically resulted in numerous telephone calls to other providers and the parent, to develop and implement a plan of care and monitor the child’s response.

Figure 1.

Frequency of care coordination episodes over three-year period, by subject

Figure 2.

Frequency of care coordination episodes over three-year period, by initiating reason

Figure 3.

Frequency of care coordination episodes over three-year period, by initiating person

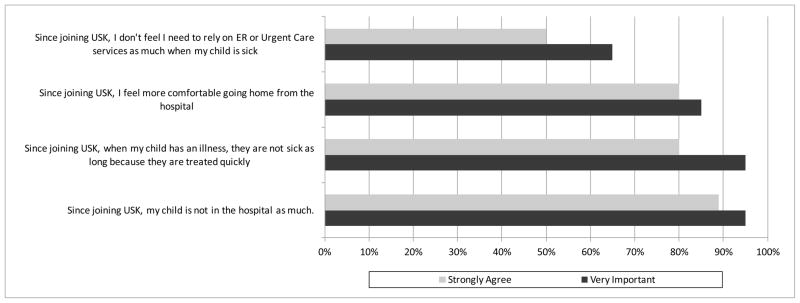

Descriptive analysis of the program-specific survey focused on parental perception of the USK program. The majority of parents rated the following as “very important”: 1) a single place to call; 2) assistance in managing their child’s complex condition; 3) organized and accessible medical information; and 4) someone who clarifies orders for other providers. Parental perception of the USK program’s impact on health service use is shown in Figure 4. Over half the families reported reliance on ER and Urgent Care services when their child was sick. The majority of parents “strongly agreed” their child was not sick as long and had fewer hospitalizations since joining the USK program.

Figure 4.

Parental perception of the effects of U Special Kids program on health service use

Discussion

This study investigated the attributes of telehealth interactions of APRNs utilizing relationship-based care coordination for children enrolled in the USK Program, a tertiary health care home for CMC. Retrospective review of 2,628 care coordination episodes conducted by telehealth for 27 CMC during a consecutive three-year time period indicated the majority of episodes were initiated by parents, and the primary reason for initiating an episode was acute and chronic condition management. This finding is similar to Flannery, Phillips & Lyons (2009) prospective review of outpatient oncology telephone calls, answered by registered nurses and APRNs utilizing guidelines-based management and care coordination. Over half the calls were initiated by patients or families and the majority were related to condition management (Flannery, Phillips, & Lyons, 2009).

The persons and reasons for initiating care coordination episodes reflect an interesting pattern (Figs 2 & 3). From year one to year two, episodes in all six initiating reason categories doubled and episodes initiated by parents tripled. From year two to year three, the total number of episodes changed little, but the categories ‘care coordination with community resources’ and ‘parental follow-up, education and support’ increased modestly while all other categories decreased. These patterns could be explained by a recurrent theme from the USK APRN interviews: the importance of teaching parents how to monitor and manage their child’s health. APRNs are skilled in recognizing the complexity of acute and chronic health conditions and the risk for adverse outcomes (Looman et al., 2013; APRN consensus model and endorsing organizations ). The USK APRNs helped families proactively identify health changes, and managed and monitored the child’s progress through telehealth. This finding is supported by a previously reported reduction in hospitalizations for children enrolled in the USK program (Cady et al., 2009), and other care coordination research that showed similar hospitalization trends (Barry et al., 2002; Palfrey et al., 2004).

The statistically significant increase in the frequency of a subject’s care coordination episodes between year one and year two of the data collection period could be related to the time enrolled in the USK program. Almost 60% of the children included in this retrospective review where enrolled in the program less than two years. As the amount of time enrolled increased, parental experience initiating care coordination episodes could increase. The small number of newly enrolled children (n=16) in this review limits the power of evaluating whether length of time enrolled in the program is a predictor of care coordination frequency. Another explanation for the significant increase from year one to year two could be the unpredictable health trajectory of CMC. Despite the limitations, these findings could illustrate the value of the APRNs advanced scope of practice and specialized education in delivering high nurse-dose care coordination for children with medical complexity (Looman et al., 2013).

The program-specific survey indicates parental perception of assistance managing their child’s complex condition and having someone clarify and coordinate care amongst their child’s different providers. The majority of care coordination episodes were initiated by parents, and episodes initiated for care coordination with community resources increased over the three year period. This suggests the value of a ‘dedicated place’ that all persons involved in a child’s care can easily access to obtain or clarify information, and utilize to resolve issues and manage care. A qualitative study of care coordination attributes as perceived by staff and families from seven spina bifida clinics supports these findings. Families using these clinics valued a single contact person, frequent telephone communication between clinic visits, referrals to community services and a focus on proactive care for their child (Brustrom, Thibadeau, John, Liesmann, & Rose, 2012).

Implications for Policy, Research and Practice.

Reversing the exponential rise in health care costs requires innovative models that address the high intensity and unique needs of children with medical complexity. This study identified the reasons for and the people initiating care coordination for CMC in the USK program. High-intensity relationship-based APRN care coordination, delivered via telehealth, showed an increase in the frequency of parent initiated episodes and an increase in the frequency of acute and chronic condition management episodes. Shifting from high-cost acute inpatient care to lower-cost outpatient health management care is the primary goal of health reform initiatives, specifically accountable care organizations. APRN care coordination that is relationship-based and delivered by telehealth has the potential to change how families of CMC manage their child’s care. Future studies are needed to evaluate the impact of APRN models for CMC. Developing methodology that identifies this small sub-group of children, followed by comprehensive evaluation of the APRN care coordination model is a critical first step in meeting this challenge.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Nancy Hoogenhous, MS, CPNP and Barbara Peterson, MS, CPNP for assistance with data collection and insight into APRN care coordination.

This project was supported in part by grant 1R01NR010883 from the National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Rhonda G. Cady, Lab Medicine and Pathology, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Anne M. Kelly, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Stanley M. Finkelstein, Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Wendy S. Looman, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Ann W. Garwick, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities. Care coordination in the medical home: Integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1238–1244. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonelli RC, Antonelli DM. Providing a medical home: The cost of care coordination services in a community-based, general pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1522–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APRN consensus model and endorsing organizations. Retrieved 4/15, 2013, from http://www.nursingworld.org/HomepageCategory/NursingInsider/Archive_1/2009-NI/Feb09NI/APRN-Consensus-Model-Endorsing-Organizations-.html.

- Barry TL, Davis DJ, Meara JG, Halvorson M. Case management: An evaluation at childrens hospital los angeles. Nursing Economic$ 2002;20(1):22–7. 36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brustrom J, Thibadeau J, John L, Liesmann J, Rose S. Care coordination in the spina bifida clinic setting: Current practice and future directions. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2012;26(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady RG, Finkelstein SM, Kelly A. A telehealth nursing intervention reduces hospitalizations in children with complex health conditions. Journal of Telemedicine & Telecare. 2009;15(6):317–320. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2009.090105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cady RG, Kelly A, Finkelstein SM. Home telehealth for children with special health-care needs. Journal of Telemedicine & Telecare. 2008;14(4):173–177. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2008.008042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Kuo D, Agrawal R, Berry J, Bhagat S, Simon T, et al. Children with medical complexity: An emerging population for clinical and research initiatives. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):529–538. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen E, Berry JG, Camacho X, Anderson G, Wodchis W, Guttmann A. Patterns and costs of health care use of children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1463–e1470. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiano PC, Momany ET, Tyler MC, Penziner AJ, Lobas JG. Cost of outpatient medical care for children and youth with special health care needs: Investigating the impact of the medical home. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4):e1187–94. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery M, Phillips SM, Lyons CA. Examining telephone calls in ambulatory oncology. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2009;5(2):57–60. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0922002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J, Colby H, Bartelt T, Jablonski D, Krauthoefer M, Havens P. A tertiary care primary care partnership model for medically complex and fragile children and youth with special health care needs. Archives of Pediatrics Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(10):937–944. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.10.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams K, Corrigan JM, editors. Institute of Medicine. Priority areas for national action: Transforming health care quality. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A, Golnik A, Cady R. A medical home center: Specializing in the care of children with special health care needs of high intensity. Maternal & Child Health Journal. 2008;12(5):633–640. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Burns CM, Davidson PW, McAnarney ER. Effects of providing comprehensive ambulatory services to children with chronic conditions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(10):1003–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.10.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looman WS, Presler E, Erickson MM, Garwick AW, Cady RG, Kelly AM, et al. Care coordination for children with complex special health care needs: The value of the advanced practice nurse’s enhanced scope of knowledge and practice. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2013;27(4):293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister JW, Presler E, Cooley WC. Practice-based care coordination: A medical home essential. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):e723–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Arango P, Fox H, Lauver C, McManus M, Newacheck PW, et al. A new definition of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102(1 Pt 1):137–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAPNAP. NAPNAP position statement on pediatric health care/medical home: Key issues on delivery, reimbursement, and leadership. 2009 Retrieved 4/15, 2013, from http://www.napnap.org/PNPResources/Practice/PositionStatements.aspx.

- National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs 2009/10. Data query from the child and adolescent health measurement initiative. 2012 Retrieved 04/21, 2013, from http://www.childhealthdata.org.

- Newacheck PW, Kim SE. A national profile of health care utilization and expenditures for children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(1):10–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfrey JS, Sofis LA, Davidson EJ, Liu J, Freeman L, Ganz ML. The pediatric alliance for coordinated care: Evaluation of a medical home model. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5 Suppl):1507–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, & Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Chronic care: Making the case for ongoing care. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant PW, Pearce MS, Bythell M, Rankin J. 20-year survival of children born with congenital anomalies: A population-based study. The Lancet. 2010;375(9715):649–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61922-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weed LL. Medical records, patient care, and medical education. Irish Journal of Medical Science. 1964;39(6):271–282. doi: 10.1007/BF02945791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise PH. The transformation of child health in the united states. Health Affairs. 2004;23(5):9–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.5.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt JC, Liu JL. Basic concepts in medical informatics. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2002;56(11):808–812. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.11.808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]