Abstract

Background: Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a very high risk cardiovascular disease population and should be treated aggressively. We investigated lipid management in CKD patients with atherosclerosis in Taiwan.

Methods: 3057 patients were enrolled in a multi-center study (T-SPARCLE). Lipid goal are defined as total cholesterol (TC) < 160mg/dl, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) <100 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) > 40 mg/dl in men, HDL > 50 mg/dl in women, non-HDL cholesterol < 130mg/dl, and triglyceride < 150 mg/dl.

Results: Compared with those without CKD (n=2239), patients with CKD (n=818) had more co-morbidities (hypertension, glucose intolerance, stroke and heart failure) and lower HDL but higher triglyceride levels. Overall 2168 (70.5%) patients received lipid-lowering agents. There was similar equivalent statin potency between CKD and non-CKD groups. The goal attainment is lower in HDL and TG in the CKD group as compared with non-CKD subjects (47.1 vs. 51.9% and 63.2 vs. 68.9% respectively, both p < 0.02). Analysis of sex and CKD interaction on goals attainment showed female CKD subjects had lower non-HDL and TG goals attainment compared with non-CKD males (both p < 0.019).

Conclusion: Although presenting with more comorbidities, the CKD population had suboptimal lipid goal attainment rate as compared with the non-CKD population. Further efforts may be required for better lipid control especially on the female CKD subjects.

Keywords: lipid, chronic kidney disease, goal, atherosclerosis.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global public problem 1. Patients with CKD have higher risk of progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and poor cardiovascular prognosis 2. Taiwan has been recognized as an epidemic area of kidney disease with the highest incidence and prevalence rates of ESRD in the world 3. Although the nationwide CKD Preventive Project with multidisciplinary care program has proved its effectiveness in decreasing dialysis incidence, mortality and medical costs, the numbers of CKD population are still growing as the increasing prevalence of comorbidities such as dyslipidemia, hypertension and diabetes in Taiwan as well as in the worldwide 4. Therefore, the development of effective treatment strategies is mandatory for such high cardiovascular risk population.

The lipid profile worsens with the declining of glomerular filtration rate (GFR). It comprises elevations of triglyceride (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), non-high denisty lipoprotein cholesterol (non-HDL-C) and lowering of HDL-C. Altogether, most patients with CKD have mixed dyslipidaemia and the lipid profile is highly atherogenic with adverse changes in all lipoproteins 5. Tonelli et al. recently reports the risk of coronary events in people with CKD is compared with those with diabetes in a population-level cohort study 6. European lipid treatment guideline has also acknowledged patients with CKD as a very high risk cardiovascular disease population and should be treated aggressively 5.

Previous analysis found lipid-lowering treatment may preserve GFR and may decrease proteinuria in patients with renal disease 7. Recent SHARP trial found major atherosclerotic events and major vascular events were reduced in CKD patients on lipid-lowering treatment 8. Because lipid-lowering therapy has been shown to reduce the atherosclerotic events in the patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD) or CKD, it is mandatory to survey the current status of lipid-lowering agents use, which might provide new insight to treat such high risk population. In this study we investigated the factors associated with the presence of CKD and the impact of CKD on clinical characteristics, lipid management and goal attainment in patients with established CVD.

Methods

Design

The cross-sectional observational registry (T-SPARCLE) was intended to document the current clinical practice of caring for patients with established CVD, focusing on lipid management in medical centers across all regions in Taiwan, including public and private hospitals, academic medical centers, and regional hospitals 9. The medications prescribed were at the discretion of the primary treating physicians; in addition, the patients or the physicians were free to withdraw from this registry at any time, for any reason. There was also a longitudinal follow-up of these patients for 5 years. The present paper only analyzed the baseline data.

Eligibility and inclusion criteria

This study is a multi-center registry facilitated by cardiologists, diabetologists, neurologists, or nephrologists. Potentially eligible patients were invited for a screening visit, where non-probability sampling will be applied, including consecutive patients who meet eligibility criteria.

Male and female patients with stable symptomatic atherosclerotic disease over 18 years of age were enrolled from the 14 participating sites. The definitions of coronary atherosclerosis were the presence of significant coronary artery stenosis of > 50% in diameter exhibited through cardiac catheterization examination, having a history of myocardial infarction (MI) as evidenced by electrocardiography (ECG) or hospitalization, or angina showing ischemic ECG changes or positive response to stress test. Patients with cerebral vascular disease, defined as cerebral infarction, intra-cerebral hemorrhage (excluding intra-cerebral hemorrhage associated with trauma or other diseases), and transient ischemic attack whose carotid artery ultrasound confirms atheromatous change with more than 70% stenosis, were included. Peripheral atherosclerosis with symptoms of ischemia and confirmed by ankle-brachial index, Doppler ultrasound, or angiography were included.

Exclusion Criteria

The main exclusion criteria were refusal to provide necessary informed consent, neurocognitive or psychiatric condition which prevents reliable clinical data (as judged by investigators) from being obtained, life expectancy of less than 6 months (e.g., malignant metastatic neoplasm), hemodynamically significant valvular or congenital heart disease, treatment with immunosuppressive agents, or any other condition or situation which, in the opinion of the investigator, was deemed unsuitable for this registration. Patients were not allowed to participate if they had experienced an acute stroke, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), or coronary revascularization procedure within the past 3 months, or had been scheduled to undergo coronary bypass graft surgery or valvular surgery before study enrollment.

Study protocol

All potential patients were screened for eligibility by means of a screening visit. Those who fulfill the inclusion criteria at the screening visit were invited to join the registry study. Regular patients' follow-ups were taken place at the 6th, 12th, and 18th month, and every year thereafter for a total of 5 years through clinical visits, follow-up phone-calls, or record review from the National Health Insurance Bureau (NHIB) of Taiwan.

At every clinical visit, vital signs, clinical endpoints, adverse events, concurrent medication information and laboratory specimens were obtained as thoroughly as possible; however, when phone calls or records from NHIB were involved, only clinical endpoints were recorded. The lipid profile was evaluated at baseline, and every year thereafter. While addressing the lipid control and other medical needs of study patients, the investigators followed the recommendations from the NHIB regarding lipid-lowering guidelines. If the primary treating physician intended to treat the patient's lipid profile to the target, he/she could add, remove or adjust the lipid-lowering drugs according to his/her clinical judgment.

Calculation of kidney function and definition of CKD

The estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated with the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equation [GFR = 186.3 × (serum creatinine in mg/dl)-1.154× (age)-0.203× (0.742 if female)] 10. CKD was defined as a GFR less than 60 ml/min per1.73 m2. This range corresponds to stage 3 or higher CKD by the National Kidney Foundation's classification scheme and helps identify individuals with clinically significant CKD 12.

Lipid-lowering treatment and lipid goals

The blood samples were collected after at least 8 hours fasting. LDL cholesterol level was directly measured. The atorvastatin 10mg is considered as the standard dose which is considered to be equal potency to simvastatin 20 mg, pravastatin 40mg and fluvastatin 80mg. The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who attained a serum level of total cholesterol (TC) < 160, LDL-C < 100, non-HDL-C < 130, HDL > 40 in men, HDL > 50 in women, TG < 150 mg/dl or all-five goals attainment 12, 13.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables will be expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Qualitative variables will be presented in both absolute frequencies (number of patients) and relative frequencies (percentage). Chi-square test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used to compare categorical data and non-parametric data respectively. The t test was used for analysis between continuous variables. A statistical adjustment using binary logistic regression analysis was performed to analyze factors associated with presence of CKD. The relevant correlated variables were analyzed in the logistic regression analysis. All tests were 2-sided, and the level of significance was established as p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software package version 17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating site. All patients gave their written informed consent before entering the study. This clinical trial was conducted not only in accordance with the principles of the current revision of the Declaration of Helsinki and the latest version of the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) but also according to the local and regulatory legal requirements enforceable in Taiwan. Ethics committee approval was obtained at all trial sites including institutional review board (IRB) of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, IRB of National Cheng Kung University Hospital, IRB of Tainan Municipal Hospital, IRB of Taichung Veterans General Hospital, IRB of E-DA Hospital, IRB of Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, IRB of Chung Shan Medical University, IRB of Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, IRB of Taipei City Hospital Heping Fuyou Branch, IRB of Taipei City Hospital Renai Branch, IRB of Mackay Memorial Hospital, IRB of National Taiwan University Hospital, IRB of Cheng-Hsin General Hospital, and IRB of Taipei Veterans General Hospital.

Results

Baseline characteristics

From January, 2010 to February, 2011, a total of 3316 patients were enrolled. Among them, 3057 (92.2%) patients had renal function evaluation were finally included in this study. Their mean age was 65.8±11.9 years and 68.6% of them were males. Among them, 818 (26.8%) patients had CKD. The baseline clinical characteristics of the CKD and non-CKD populations were shown in Table 1. Compared with patients without CKD, those with CKD were older with higher waist and more co-morbidity including hypertension, heart failure, stroke, glucose intolerance, and lower frequencies of alcohol drinking and physical exercise (all p < 0.04). Patients with CKD had lower HDL-C, GOT, GPT, hemoglobin and platelet counts but higher TG level. Besides, CKD patients received more evidence-based medicine for atherosclerosis including clopidogrel, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) and calcium channel blocker (all p < 0.01). They also received more diuretic and α-blocker but less angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors than non-CKD patients (all p ≦ 0.02). Binary logistic regression analysis found that lower hemoglobin and platelet counts, old age, higher waist, TG and systolic blood pressure, presence of hypertension were related to the presence of CKD (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics between CKD and non-CKD population.

| Number (%)/Mean (SD) | CKD (N=818) | non-CKD (N=2239) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 546 (66.75%) | 1552 (69.32%) | 0.18 |

| Age (years) | 71.85±10.48 | 63.52±11.63 | <0.01 |

| Waist (cm) | 95.49±12.35 | 93.22±10.58 | <0.01 |

| Hip (cm) | 101.0±9.04 | 100.8±8.62 | 0.45 |

| Height (cm) | 161.4±8.28 | 163.2±8.32 | <0.01 |

| Weight (kg) | 68.62±11.74 | 70.27±12.83 | <0.01 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.31±4.57 | 26.32±3.92 | 0.95 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 135.2±19.94 | 131.5±16.55 | <0.01 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 75.28±12.87 | 75.96±10.58 | 0.19 |

| Pulse rate (beats/min) | 75.33±13.04 | 74.84±12.63 | 0.42 |

| Family history of CVD (%) | 180 (25.94%) | 633 (34.09%) | 0.01 |

| Family history of diabetes (%) | 158 (22.93%) | 511 (27.82%) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension (%) | 675 (84.69%) | 1629 (75.28%) | <0.01 |

| Heart failure (%) | 114 (14.88%) | 156 (7.90%) | <0.01 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 543 (69.97%) | 1395 (71.03%) | 0.58 |

| Ischemic stroke (%) | 99 (12.99%) | 202 (10.20%) | 0.04 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke (%) | 29 (3.84%) | 37 (1.90%) | <0.01 |

| Transient ischemic accident (%) | 29 (3.83%) | 49 (2.51%) | 0.07 |

| Diabetes, IFG, or IGT (%) | 398 (50.38%) | 856 (41.65%) | <0.01 |

| Smoking (%) | 280 (34.23%) | 811 (36.22%) | 0.31 |

| Alcohol drinking (%) | 56 (6.85%) | 339 (15.19%) | <0.01 |

| Regular exercise | 293 (35.86%) | 1066 (47.61%) | <0.01 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 174.0±44.00 | 173.3±39.12 | 0.68 |

| Non-HDL-C (mg/dL) | 129.4±41.98 | 127.4±38.02 | 0.24 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 44.6±13.22 | 45.87±14.44 | 0.03 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 99.65±35.40 | 101.0±33.76 | 0.34 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 148.3±86.32 | 136.9±93.53 | <0.01 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.73±1.21 | 0.91±0.19 | <0.01 |

| AC sugar (mg/dL) | 120.3±40.27 | 117.1±41.06 | 0.07 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.38±3.99 | 7.19±4.65 | 0.39 |

| GOT (mg/dL) | 27.14±17.39 | 29.68±17.97 | 0.01 |

| GPT (mg/dL) | 24.22±13.84 | 30.40±21.25 | <0.01 |

| CPK (mg/dL) | 122.5±125.7 | 136.4±362.7 | 0.29 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.91±2.01 | 15.33±40.79 | 0.04 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 38.8±5.65 | 45.34±133.7 | 0.1 |

| RBC (×106/μL) | 4.26±0.69 | 4.63±1.69 | <0.01 |

| WBC (×103/μL) | 7.46±6.18 | 7.64±9.38 | 0.63 |

| Platelet (×103/μL) | 204±63.91 | 216.3±61.91 | <0.01 |

| Aspirin | 497 (60.76%) | 1386 (61.90%) | 0.56 |

| Clopidogrel | 163 (19.93%) | 352 (15.72%) | <0.01 |

| ACEI | 104 (12.71%) | 362 (16.17%) | 0.02 |

| ARB | 461 (56.36%) | 1061 (47.39%) | <0.01 |

| β-blocker | 439 (53.67%) | 1196 (53.42%) | 0.9 |

| CCB | 300 (36.67%) | 632 (28.23%) | <0.01 |

| Diuretic | 94 (11.49%) | 164 (7.32%) | <0.01 |

| α-blocker | 61 (7.46%) | 83 (3.71%) | <0.01 |

| Central-acting anti-HT agents | 0 | 1 (0.04%) | 0.55 |

| Anti-arrhythmics | 8 (0.98%) | 15 (0.67%) | 0.38 |

| Steroid | 2 (0.24%) | 0 | 0.07 |

| Anti-diabetic agent | 193 (23.59%) | 464 (20.72%) | 0.09 |

| Insulin | 1 (0.12%) | 3 (0.13%) | 0.94 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; IFG, impaired fasting glucose; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin-II receptor blockers; CCB, calcium channel blockers

Table 2.

Factors associated with presence of CKD after multivariate analysis.

| Variables | OR | 95% Confidence Interval | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.06 | <.0001 |

| Waist (cm) | 1.03 | 1.006 | 1.055 | 0.0133 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 1.009 | 1 | 1.018 | 0.0408 |

| Hypertension | 1.59 | 1.037 | 2.436 | 0.0333 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 1.005 | 1.002 | 1.007 | <.0001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.756 | 0.667 | 0.856 | <.0001 |

| Platelet (×103/μL) | 0.995 | 0.992 | 0.998 | 0.0006 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Lipid-lowering agents use and goals attainment

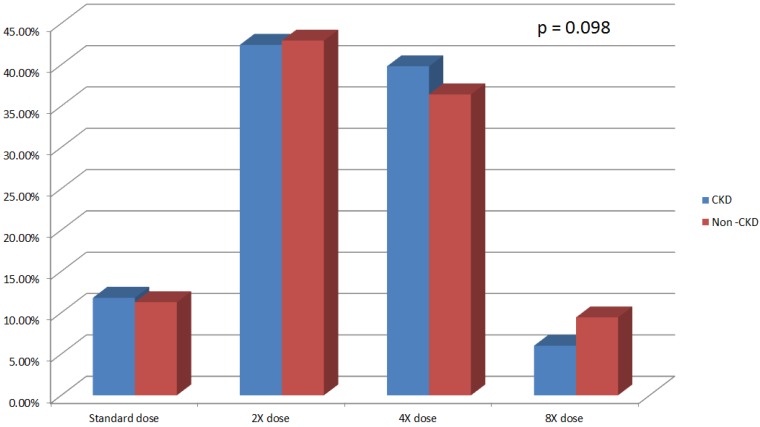

Overall 2168 (70.5%) patients had lipid-lowering agent treatment. Among the 818 CKD subjects 581 (71.0%) patients had lipid-lowering agent treatment (Table 3). CKD and non-CKD subjects received equivalent potency statin treatment at baseline (p = 0.098) (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Lipid-lowering agents use.

| Statin | Fibrate | Others | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients | |||

| ● | 1816 | ||

| ● | 112 | ||

| ● | 13 | ||

| ● | ● | 55 | |

| ● | ● | 161 | |

| ● | ● | 4 | |

| ● | ● | ● | 7 |

| 889 | |||

| CKD Patients | |||

| ● | 489 | ||

| ● | 37 | ||

| ● | 5 | ||

| ● | ● | 17 | |

| ● | ● | 30 | |

| ● | ● | 1 | |

| ● | ● | ● | 2 |

| 237 | |||

Others include ezetimibe, cholestyramine and acipimox; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Figure 1.

Statin use and potency in CKD and non-CKD population. CKD, chronic kidney disease.

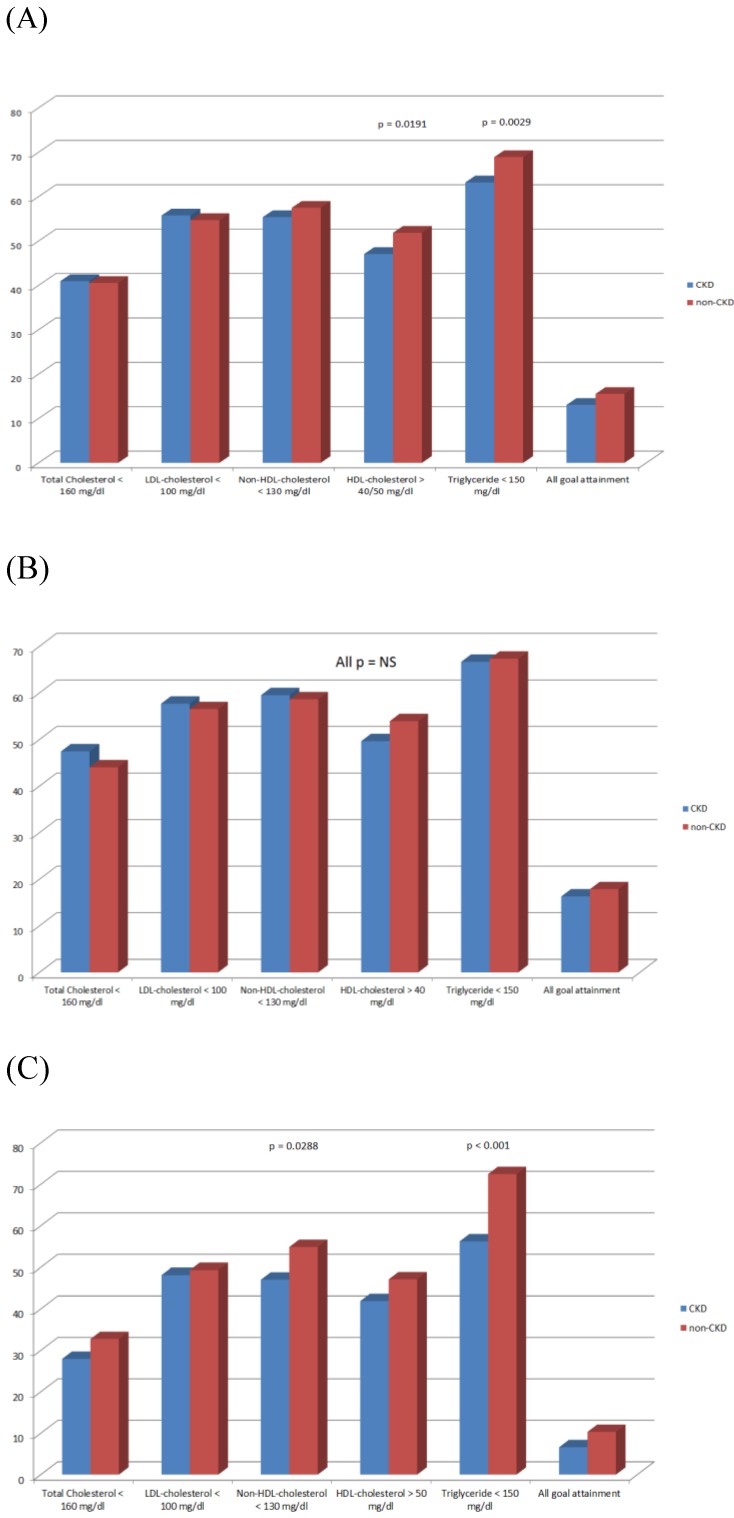

Overall there were no statistical significances in TC, LDL-C, non-HDL-C and all-five-lipid goals attainment between CKD and non-CKD population (40.95 vs. 40.55%, 55.75 vs. 54.71%, 55.38 vs. 57.48%, and 13.08 vs 15.54%, respectively, all p > 0.05). Patients with CKD had lower HDL-C and TG goals attainment than non-CKD population (47.07 vs. 51.85% and 63.20 vs. 68.91%, p = 0.019 and 0.030, respectively) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Goal attainments in (A) all patient population, (B) male patients, and (C) female patients. CKD, chronic kidney disease.

There is no interaction between statin use and CKD on all lipid goal attainments. When we analyzed only patients (n = 2168) receiving lipid-lowing agents treatment, CKD patients had similar TC, LDL-C, non-HDL-C and HDL-C levels (173.70±45.66 vs. 171.90±40.87 mg/dl, 98.12±36.09 vs. 98.89±34.40 mg/dl, 129.1±43.87 vs. 126.5±39.86 mg/dl and 44.61±13.55 vs. 45.44±14.36 mg/dl, all p > 0.05) but higher TG levels (153.40±91.41 vs. 142.20±102.30 mg/dl, p = 0.0149). CKD subjects had lower HDL-C (46.64 vs. 51.48%, p = 0.046) and TG (61.45vs 67.74%, p = 0.0061) goals attainment but similar TC (42.51 vs. 44.23%, p = 0.4742), LDL-C (59.38 vs. 58.41%, p = 0.6851) and non-HDL-C (57.49 vs. 59.99%, p = 0.2939) goals attainment than non-CKD population. If LDL goal was set as < 70 mg/dL as the updated guideline suggestion, more CKD patients receiving lipid-lowering agent attained the target than non-CKD population (23.06 vs. 18.65%, p = 0.0225).

Gender and goal attainment

In the male subgroup, there was no statistical difference in all lipid goals attainment between CKD and non-CKD groups. Female CKD subjects had lower non-HDL-C and TG goals attainment (47.06 vs. 54.88% and 56.25 vs. 72.49%; p = 0.0288 and p < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 2B and C).

There is an interaction between sex and CKD on the non-HDL and TG goals attainment (p = 0.0463 and 0.0002, respectively). In females without and with CKD, the non-HDL-C goals attainment were significantly lower (OR 0.612, 95% CI: 0.461-0.813; p = 0.0007 and OR 0.398, 95% CI: 0.249-0.636; p = 0.0001, respectively) compared to the non-CKD males. Furthermore, CKD females had lower TG goal attainment (OR 0.571, 95% CI: 0.358-0.910; p = 0.0184) compared to the non-CKD males (Table 4).

Table 4.

Interaction between sex, non-HDL-C and TG goals attainment.

| CKD | Sex | Non-HDL-C<130 | Non-HDL-C≧130 | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Male | 63.59% | 36.41% | 1 | |

| - | Female | 51.68% | 48.32% | 0.612(0.461,0.813) | 0.0007 |

| + | Male | 64.83% | 35.17% | 1.055(0.818,1.361) | 0.6795 |

| + | Female | 41.03% | 58.97% | 0.398(0.249,0.636) | 0.0001 |

| CKD | Sex | TG<150 | TG≧150 | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

| - | Male | 69.39% | 30.61% | 1 | |

| - | Female | 72.69% | 27.31% | 1.174(0.858,1.607) | 0.3165 |

| + | Male | 67.44% | 32.56% | 0.914(0.704,1.186) | 0.4977 |

| + | Female | 56.41% | 43.59% | 0.571(0.358,0.910) | 0.0184 |

TG, triglyceride, HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Discussion

There were four major findings in this atherosclerotic cohort study. First, atherosclerotic patients with CKD had more comorbidities and received more evidence-based medicine than those without CKD. Second, patients with and without CKD received equal potency statin. Third, lipid goal attainment was suboptimal and lower in CKD subjects especially in HDL and TG. Fourth, female subjects had higher percentage not to attain lipid goals especially in TG and non-HDL-C.

CKD is an important poor predictor of prognosis in those with atherosclerosis 11, 12. More extensive and severe atherosclerosis coronary tree with plaque composed of greater necrotic core and less fibrous tissue were found in the CKD than non-CKD subjects 13. Although there is no particular reason not to treat CKD patients just like patients without renal dysfunction, physicians prescribed fewer guideline-recommended treatments even in the absence of contraindications 14. Furthermore, poor awareness of CKD and its risk in patients with CAD is a big challenge both for the physcians and patients 15. As shown in our study, those with CKD had more comorbidities and received more guideline-recommended medications. Because education and prevention strategies are very important both for physcians and CKD patients, our nationwide CKD Preventive Project with multidisciplinary care programmay play an important role in prescribing the evidence-based medicine by physcians in Taiwan 4.

Statin can be effectively used in the primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention. Patients with CKD have atherogenic lipid profiles and suffer from high rates of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality 5. Recently, Tonelli et al. also reported that the risk of coronary events in people with CKD was compared with those with diabetes 6. Although few studies enrolled CKD only subjects to test the statin efficacy, statins were shown to effectively lower LDL and be safe in CKD population 8, 14. Statins can decrease mortality and cardiovascular events in CKD persons without dialysis 8, 15. Therefore, ESC guideline suggests that LDL lowering with statin to reduce cardiovascular disease should be considered 5. Among our 818 CKD subjects, 581 (71.0%) patients had lipid-lowering agent treatment and 538 (65.8%) patients received statin treatment. Considering the suboptimal LDL and non-HDL-C target attainment, higher TG and lower HDL levels in the CKD population and only equal potency statin use between the two groups, it is mandatory to educate and ecourage our physcians to prescribe more statins for CKD patients.

Because CKD is acknowledged as a CAD risk equivalent, guidelines has set the LDL-C reductions as the primary target of therapy. Non-HDL-C should be the second objective in the management of mixed dyslipidaemia 5. The 2007 KDOQI guideline suggested that the target LDL-C in people with diabetes and CKD stages 1-4 should be < 100 mg/dl and a level of <70 mg/dl is a therapeutic option 16. The 2011 European guideline suggested that CKD patients are the very high CV risk group and the treatment target is less than 70 mg/dL for LDL-C or a ≥50% reduction from baseline LDL-C as the class I level A recommendation 5. In our study population the LDL < 100 mg/dl and non-HDL-C < 130 mg/dl goals attainment were equal between CKD and non-CKD population whether they received lipid-lowering agents or not. Surprisingly, we found the percentages of CKD population with LDL < 70 mg/dl were higher than non-CKD population whether they received lipid-lowering agents or not. This may partially reflect the success of the nationwide CKD Preventive Project with multidisciplinary care program in Taiwan 4. Howevere, the percentage LDL goal attainment was only 56% in the CKD population and there were lower TG and HDL-C goals attainment. Therefore, there was room for improvement. New strategies and education to physcians and the public are still needed.

The antiplatelet effects of aspirn, clopidogrel and dual combination were reported to have conflict results in the CKD population. Recent studies have shown that CKD is accompanied by a low platelet inhibitory response to clopidogrel administration 17, 18. However, Kaufman et al. found that clopidogrel significantly inhibits ADP-induced platelet aggregation even in subjects receiving chronic maintenance hemodialysis 19. Cuisset et al. also found that no significant difference between patients with or without CKD by two platelet function tests in ACS population 20. Furthermore, in the CURE trial, clopidogrel was beneficial and safe in patients with and without CKD 21. In our study, CKD patients received more clopidogrel tratment than non-CKD patients. These atherosclerotic patients will be followed up to see if there are potential beneficial effects of clopidogrel in next fives years.

Although female gender may be associaed with higher likelihood of muscle side effects with statins, there was no heterogeneity in treatment effect between men and women in primary and secondary prevention 22, 23. Therefore, statin treatment is recommended for primary and secondary prevention in women with the same indications and targets as that in men 5. However, previous studies indicated that compared to the females, male subjects ususally have higher percentage to attain LDL goal 24, 25. Limited studies reported the gender issue on the lipid goal attainment in CKD populatin. Stadler et al. reported that male sex is a predictor for LDL less than 100 mg/dl in the CKD patients without coronary artery disease. Our study could be the first one showing the interaction between sex and CKD on the non-HDL and TG goals attainment in the established atherosclerosis population. CKD females had lower non-HDL-C and TG goals attainment compared to the non-CKD males. Further studies are required to confirm the gender disparity and to elucidate which factors may be at play in the CKD population.

Limitations

This study may have some main limitations. Firstly, it is a nonrandomized and observational study. Nonetheless, this study provided valuable real-world data on the current practices across the established atherosclerotic population, which could help to improve the lipid management in the CKD population. Second, this was a cross-sectional study evaluating lipid measurement and treatment practices at a single time point as such temporal changes over time were not assessed. However, these patients are currently under follow-up for the interaction of lipid management and the cardiovascular outcome in next fives years. Third, the potential reasons for patients not on lipid-lowering therapy may be related to the reimbursement indication of the Taiwan NationaI Health Insurance Bureau lipid guideline, physicians' innertia, patients' intolerances, nonadherence, or refusal. However, the above were not analyzed in this study, which may possibly influence the goals attainment in our study cohorts. Fourth, the CKD was defined by the presence of estimated GFR less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 in this study. The diagnostic criteria for CKD also includes an albumin-creatinine ratio of 30 mg/g or greater in the KDIGO guideline. However, in this registry we had not collected albuminuria/proteinuria which accumulated evidence has linked to risks for adverse cardiovascular and kidney outcomes. Fifth, we had not collected c-reactive protein, calcium and phosphate which are related with renal deterioration in CKD.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in this real-word registry study, lipid goals attainment could be suboptimal and lower in CKD subjects especially in HDL and TG. Compared to that in males, the percentage of female subjects not to attain lipid goals was higher especially in TG and non-HDL-C. Given the high cardiovascular risk of CKD patients and the potential benefits of lipid-lowering therapy in them, more evidence-based lipid-lowering treatment may be given to CKD population, especially the female subjects, to help them attain the lipid goals. Future long-term follow-up study is also indicated to elucidate if the tight lipid control not only on LDL but also on HDL and TG may improve the clinical outcomes in such patients.

Acknowledgments

The list of the Taiwanese Secondary Prevention for patients with AtheRosCLErotic disease (T-SPARCLE) Registry Investigators:

Wei-Hsian Yin (Cheng-Hsin General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan),

Chau-Chung Wu (National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan),

Jaw-Wen Chen (Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan),

Yi-Heng Li (National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan),

Hung-I Yeh (Mackay Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan),

Ching-Chang Fang (Tainan Municipal Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan),

Kuo-Yang Wang (Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan),

Tsung-Hsien Lin (Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan), Wei-Kung Tseng (E-DA Hoispital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan),

Ai-Hsien Li (Far Eastern Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan),

Kwo-Chang Ueng (Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan),

I-Chang Hsieh (Linkou Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan),

Lien-Chi Huang (Taipei City Hospital Heping Fuyou Branch, Taipei, Taiwan),

Chiun-Hsiung Wang (Taipei City Hospital Renai Branch, Taipei, Taiwan),

Wen-Harn Pan (National Health Research Institute, Taiwan).

References

- 1.El Nahas AM, Bello AK. Chronic kidney disease: The global challenge. Lancet. 2005;365:331–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17789-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levey AS, Atkins R, Coresh J. et al. Chronic kidney disease as a global public health problem: Approaches and initiatives - A position statement from Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes. Kidney Int. 2007;72:247–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.USRDS. United Stated Renal Data System Annual Data Report. Bethesda, MD: The National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease; 2009. International comparisons; pp. 344–55. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hwang SJ, Tsai JC, Chen HC. Epidemiology, impact and preventive care of chronic kidney disease in Taiwan. Nephrology (Carlton) Suppl. 2010;2:3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation, Reiner Z, Catapano AL, De Backer G. et al. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) 2008-2010 and 2010-2012 Committees.ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1769–818. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonelli M, Muntner P, Lloyd A. et al. Alberta Kidney Disease Network.Risk of coronary events in people with chronic kidney disease compared with those with diabetes: a population-level cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:807–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60572-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fried LF, Orchard TJ, Kasiske BL. Effect of lipid reduction on the progression of renal disease: a meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2001;59:260–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharp Collaborative Group. Study of Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP): randomized trial to assess the effects of lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol among 9,438 patients with chronic kidney disease. Am Heart J. 2010;160:785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin WH, Wu CC, Chen JW. Registry of lipid control and the use of lipid-lowering drugs for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with established atherosclerotic disease in Taiwan: Rationality and methods. Int J Gerontol. 2012;6:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levey AS, Greene T, Kusek JW. A simplified equation to predict glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:A0828. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative Group. K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for Managing Dyslipidemias in Chronic Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:S1eS91. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN. et al. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association.Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–39. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navaneethan SD, Pansini F, Perkovic V. et al. HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) for people with chronic kidney disease not requiring dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD007784. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer SC, Craig JC, Navaneethan SD. et al. Benefits and harms of statin therapy for persons with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:263–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-4-201208210-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.KDOQI. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines and Clinical Practice Recommendations for Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49(2 Suppl 2):S12–154. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park SH, Kim W, Park CS. et al. A comparison of clopidogrel responsiveness in patients with versus without chronic renal failure. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1292–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angiolillo DJ, Bernardo E, Capodanno D. et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease on platelet function profiles in diabetes mellitus patients with coronary artery disease taking dual antiplatelet therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman JS, Fiore L, Hasbargen JA, O'Connor TZ, Perdriset G. A pharmacodynamic study of clopidogrel in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2000;10:127–131. doi: 10.1023/a:1018758308979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuisset T, Frere C, Moro PJ. et al. Lack of effect of chronic kidney disease on clopidogrel response with high loading and maintenance doses of clopidogrel after Acute Coronary Syndrome. Thromb Res. 2010;126:e400–2. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keltai M, Tonelli M, Mann JF. et al. CURE Trial Investigators. Renal function and outcomes in acute coronary syndrome: impact of clopidogrel. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:312–8. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000220582.19516.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety ofmore intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–1681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brugts JJ, Yetgin T, Hoeks SE. et al. The benefits of statins in people without established cardiovascular diseasebut with cardiovascular risk factors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2009;338:b2376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waters DD, Brotons C, Chiang CW. et al. Lipid Treatment Assessment Project 2 Investigators. Lipid treatment assessmentproject 2: a multinational survey to evaluate the proportion of patientsachieving low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals. Circulation. 2009;120:28–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.838466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan AT, Yan RT, Tan M. et al. Vascular Protection (VP) and Guidelines Oriented Approach to Lipid Lowering (GOALL) Registries Investigators. Contemporary management of dyslipidemiain high-risk patients: targets still not met. Am J Med. 2006;119:676–683. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]