Abstract

The fluorinated analog of deoxycytidine, Gemcitabine (Gemzar®), is the main chemotherapy in pancreatic cancer, but survival remains weak mainly because of the high resistance of tumors to the drug. Recent works have shown that the mucin MUC4 may confer an advantage to pancreatic tumor cells by modifying their susceptibility to drugs. However, the cellular mechanism(s) responsible for this MUC4-mediated resistance is unknown. The aim of this work was to identify the cellular mechanisms responsible for gemcitabine resistance linked to MUC4 expression. CAPAN-2 and CAPAN-1 adenocarcinomatous pancreatic cancer cell lines were used to establish stable MUC4-deficient clones (MUC4-KD) by shRNA interference. Measurement of the IC50 index using tetrazolium salt test indicated that MUC4-deficient cells were more sensitive to gemcitabine. This was correlated with increased Bax/BclXL ratio and apoptotic cell number. Expression of Equilibrative/Concentrative Nucleoside Transporter (hENT1, hCNT1/3), deoxycytidine kinase (dCK), ribonucleotide reductase (RRM1/2) and Multidrug-resistance Protein (MRP3/4/5) was evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and Western-blotting. Alteration of MRP3, MRP4, hCNT1 and hCNT3 expression was observed in MUC4-KD cells but only hCNT1 alteration was correlated to MUC4 expression and sensitivity to gemcitabine. Decreased activation of MAPK, JNK and NF-κB pathways was observed in MUC4-deficient cells in which NF-κB pathway was found to play an important role both in sensitivity to gemcitabine and in hCNT1 regulation. Finally and accordingly to our in vitro data, we found that MUC4 expression was conversely correlated to that of hCNT1 in tissues from patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. This work describes a new mechanism of pancreatic cancer cell resistance to gemcitabine in which the MUC4 mucin negatively regulates the hCNT1 transporter expression via the NF-κB pathway. Altogether, these data point out to MUC4 and hCNT1 as potential targets to ameliorate the response of pancreatic tumors to gemcitabine treatment.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma; drug therapy; genetics; pathology; Aged; Antimetabolites, Antineoplastic; therapeutic use; Cell Line, Tumor; Deoxycytidine; analogs & derivatives; therapeutic use; Drug Resistance, Neoplasm; genetics; Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter 1; genetics; metabolism; physiology; Female; Gene Expression Regulation, Neoplastic; physiology; Gene Knockdown Techniques; Humans; Male; Membrane Transport Proteins; genetics; metabolism; physiology; Middle Aged; Models, Biological; Mucin-4; genetics; physiology; Multigene Family; genetics; physiology; Pancreatic Neoplasms; drug therapy; genetics; pathology

Introduction

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is one of the most deadly cancers in western countries with an extremely poor prognosis (survival rate of 6 months) (1). This dramatic outcome is related to a lack of efficient therapeutic tools and early diagnostic markers. At the time of diagnosis, more than 80% of patients have metastasis or locally advanced cancer. Only about 10 to 15% of patients are considered eligible for surgical resection. Gemcitabine (Gemzar®), a fluorinated analog of deoxycytidine, is the main chemotherapy used in first-line in advanced pancreatic cancer (PC). Despite the improvement of quality life of patients, the gain in survival remains short (6 additional months). This is mainly due to the high resistance of pancreatic tumor cells to the drug (2, 3). Deciphering mechanisms responsible for PC cell resistance to gemcitabine is thus mandatory if one wants to improve efficacy of the drug and propose more efficient therapies.

One way to explain modifications of cell sensitivity to gemcitabine is an alteration of the actors responsible for its metabolism and more particularly nucleoside transporters. Gemcitabine is uptaken by the cell mainly by human Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter 1 (hENT1) and by human Concentrative Nucleoside Transporter 1 and 3 (hCNT1 and hCNT3) (4). It has been shown that expression of hENT1 and hCNT3 in pancreatic tumors are correlated with chemosensitivity and overall survival making them good predictive markers for patient survival (5–7). Moreover, hCNT1 was shown to be frequently decreased in pancreatic tumors and in most of the PC cell lines, this decrease being correlated with gemcitabine cytotoxicity suggesting the importance of hCNT1 in improving sensitivity to gemcitabine (8, 9).

Based on expression and molecular studies, mucins, especially the MUC4 mucin, have been proposed as actors of chemoresistance (10–12). MUC4 is a membrane-bound mucin which is not expressed in healthy pancreas but is expressed in the very early steps of pancreatic carcinogenesis (13). MUC4 involvement in biological properties of PC cells is well-described (14–18). However, the mechanisms linking MUC4 expression to gemcitabine sensitivity of PC cells remain to be determined.

The aim of this work was to decipher the molecular mechanisms linking MUC4 expression and gemcitabine resistance of PC cells. For that, we hypothesized that MUC4 could alter expression of actors of gemcitabine metabolism and/or detoxifying channels. We show in this paper that the loss of MUC4 in PC cells induces sensitivity to gemcitabine and involves MUC4 regulation of hCNT1 expression via the NF-κB pathway.

Results

MUC4 deficient (MUC4-KD) cells are more sensitive to gemcitabine

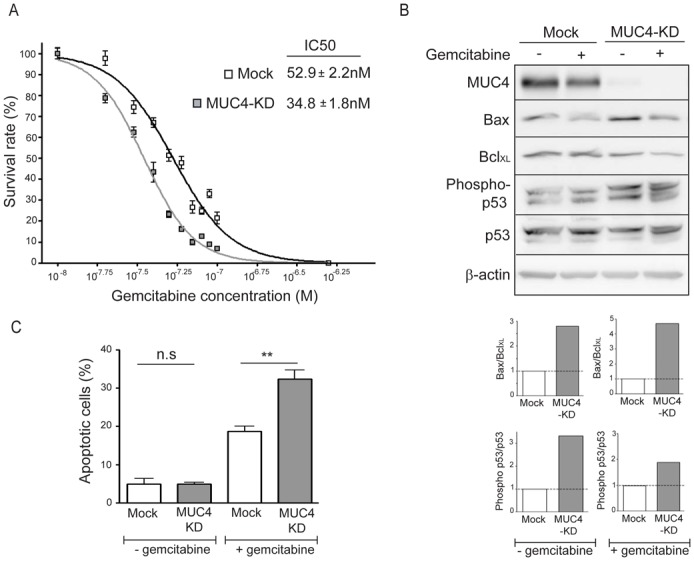

Sensitivity of MUC4 deficient cells (MUC4-KD) to gemcitabine was studied in CAPAN-2 and CAPAN-1 pancreatic cancer cells. Measurement of IC50 shows that the loss of MUC4 leads to an increased sensitivity of CAPAN-2 (MUC4-KD = 34.8 ± 1.8 nM vs. Mock = 52.9 ± 2.2 nM) (Fig. 1A) and CAPAN-1 (MUC4-KD = 80 ± 2 nM vs. Mock = 145 ± 15 nM) (supplemental Fig. 1A) cells to gemcitabine. A similar effect was observed at a longer time-point (6 days) in both CAPAN-1 and CAPAN-2 cells (data not shown). Sensitivity of MUC4-KD cells to another cytidine analog, the cytarabine/aracytin® ARA-C, was also evaluated after 72h of treatment. Interestingly, we also observed an increased sensitivity of MUC4-KD cells (IC50 = 1.3 μM ± 0.3) when compared with Mock cells (3.2 μM ± 0.6). Cell sensitivity to the alkylating agent oxaliplatin, on the other hand, was not affected by the lack of MUC4 (MUC4-KD = 1.35 ± 0.06 μM vs. Mock = 1.15 ± 0.05 μM) (data not shown). The increase of gemcitabine-induced cytotoxicity in MUC4-KD cells was accompanied by an increased expression of the pro-apoptotic marker Bax and a decreased expression of the anti-apoptotic marker BclXL leading to an increased of Bax/BclXL ratio suggesting a higher succeptibility to apoptosis in both cell lines (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. 1A). Moreover, the activation of the apoptotic mediator p53 was increased in MUC4-KD cells (Fig. 1B). To confirm these observations, the apoptotic index was determined after gemcitabine treatment by annexin-V staining followed by cytometry analysis. MUC4-KD clones, as expected, have a statistically significant higher apoptotic index than Mock cells (p=0.0025) (Fig. 1C). Altogether, these results indicate that MUC4 involvement in gemcitabine sensitivity implies alteration of the apoptotic balance in pancreatic cancer cells.

Figure 1. Sensitivity of the CAPAN-2 MUC4-KD cells to gemcitabine is correlated with apoptosis.

(A) IC50 rates were measured after 72h of gemcitabine treatment. (B) Western-blots were performed to analyse expression of MUC4, Bax, BclXL, Phospho-p53, p53 and β-actin in CAPAN-2 Mock and MUC4-KD cells. Density of each marker was measured and Bax/BclXL ratio was determined and represented as histograms. Expression in Mock cells was arbitrarily set to 1. (C) Apoptosis was studied by annexin-V/propidium iodide staining. All experiments were performed three times independently.

Alteration of gemcitabine metabolism markers expression in MUC4-KD cells

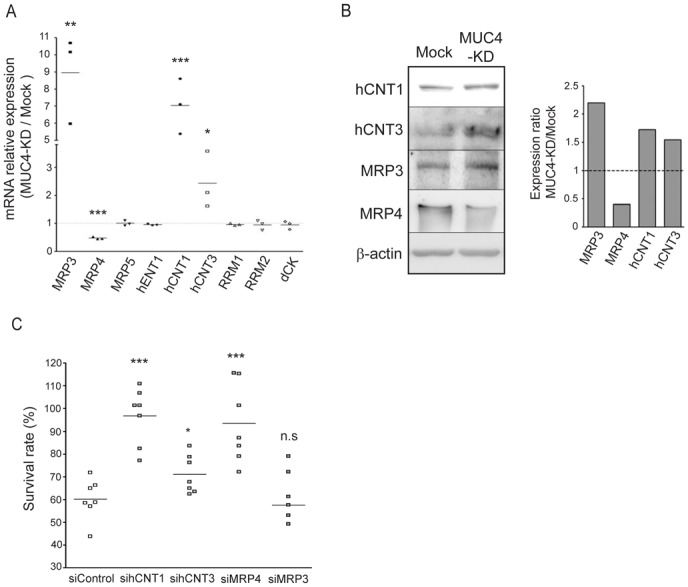

Gemcitabine efficiency depends on the state of nucleoside metabolism for its activation and incorporation into DNA. Modification of nucleoside transporters (hENT1, hCNT1 & 3) or deoxycytidine kinase (dCK) (19, 20) expression, contributes to gemcitabine efficiency. On the contrary, multidrug resistance-associated protein family (MRP) channel (21) and ribonucleotide reductase (RRM1 & 2) (22) contribute to maintaining a drug-resistant phenotype. As shown in figure 2A, CAPAN-2 MUC4-KD cells strongly overexpressed mRNA of MRP3 channel (nine-fold), hCNT1 (seven-fold) and hCNT3 (two-fold) transporters compared to Mock cells, whereas MRP4 channel mRNA expression was decreased (twofold). Increased expression of hCNT1, hCNT3 and MRP3, and decreased expression of MRP4 was confirmed at the protein level by western-blotting (Fig. 2B). Implication of these four markers in cell sensitivity to the drug was then tested by transient siRNA approach (supplemental Fig. 2A). Decreased expression of MRP3 did not alter cytotoxicity to gemcitabine (Fig. 2C), whereas hCNT1, hCNT3 and MRP4 repression led to a statistically significant (p<0.0001; p=0.0372; p=0.0007, respectively) increase in survival (Fig. 2C). These results suggest an implication of hCNT1, hCNT3 and MRP4 in gemcitabine sensitivity, with hCNT1 and hCNT3 effect correlated to both MUC4 expression and MUC4-KD cells sensitivity. In CAPAN-1 MUC4-KD cells, increased expression of hCNT1 was also found whereas hCNT3 expression remained the same when compared to Mock cells (supplemental Fig. 1B). Therefore, in the rest of the manuscript, we focused our studies on hCNT1 transporter for which biological effects were correlated to MUC4 expression in the two cell lines.

Figure 2. Expression of gemcitabine transporters and channels in CAPAN-2 MUC4-KD cells.

(A) mRNA expression of MRP3, MRP4, MRP5, hENT1, hCNT1, hCNT3, RRM1, RRM2 and dCK was analyzed in Mock and MUC4-KD cells by qRT-PCR with specific primers shown in table 1. The histogram represents the ratio of their expression in MUC4-KD versus Mock cells. (B) hCNT1, hCNT3, MRP3, MRP4 and β-actin expression by western-blotting. Bands were quantified by densitometry and shown in the histogram. (C) CAPAN-2 cells were transfected with Control (non-targeting), hCNT1, hCNT3, MRP4 or MRP3 siRNA then treated with gemcitabine. Survival rate was measured after 24h of gemcitabine treatment (100 nM) using the MTT assay. Four independent experiments were performed.

MAPK, JNK and NF-κB pathways are altered in MUC4-KD cells and modulate sensitivity to gemcitabine

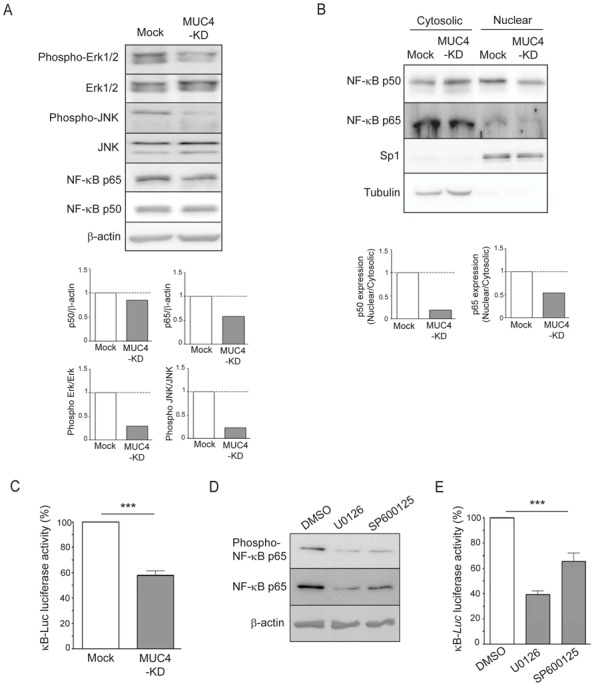

In order to understand the molecular mechanisms that regulate hCNT1 expression, we first studied alteration of the main signalling pathways in MUC4-KD cells. We show that the loss of MUC4 in both CAPAN-2 and CAPAN-1 cells induces a decrease of both Erk1/2 and JNK activation, and a decrease of NF-κB p65 expression (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. 3A). The translocation to the nucleus of NF-κB p50 and p65 sub-units was also decreased in MUC4-KD cells as the nuclear amount of the two sub-units was diminished in MUC4-KD cells compared to Mock cells (Fig. 3B). This was correlated with a decreased activity of the κB-Luc synthetic promoter (Fig. 3C and supplemental Fig. 3B). Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of the MAPK (U0126) and JNK (SP600125) pathways, induced a strong decrease of NF-κB expression (Fig. 3D) and promoter activity (Fig. 3E) suggesting a link between these pathways.

Figure 3. Expression and activity of the MAPK, JNK and NF-κB pathways in CAPAN-2 MUC4-KD cells.

(A) Expression and activation of MAPK, JNK, NF-κB p65 and p50 subunits was analysed by western-blotting on total extracts from Mock or MUC4-KD cells. (B) Expression of NF-κB p65 and p50 sub-units in cytosolic and nuclear extracts was carried out by western-blotting. Density of each western-blot was quantified and nuclear to cytosolic ratio represented as histograms where Mock was arbitrarily set to 1. (C) Luciferase activity of the κB-Luc synthetic promoter was measured 48h after transfection. Luciferase activity in Mock cells was set as 100%. (D) Western-blotting of phospho-p65 and constitutive NF-κB p65 sub-unit of CAPAN-2 cell extracts from cells treated with pharmacological inhibitors of MAPK (U0126, 10 μM) or JNK (SP600125, 10 μM) pathways during 24h. (E) Relative luciferase activity in cell extracts from CAPAN-2 cells transfected with the κB-Luc promoter followed by treatment with U0126 and SP600125 pharmacological inhibitors. DMSO (control condition) is arbitrarily set to 100%.

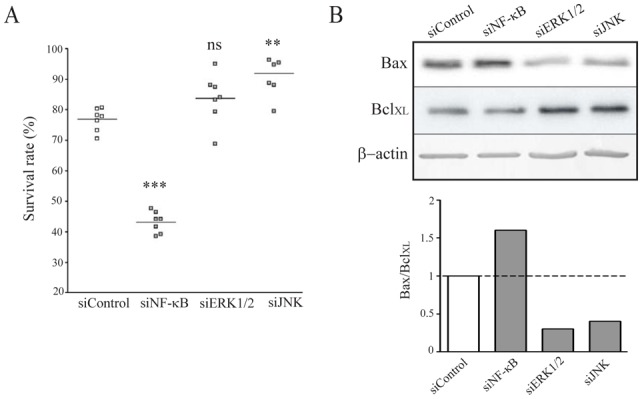

Implication of these three pathways in gemcitabine sensitivity was then investigated using specific siRNAs to target Erk1/2 and JNK kinases, and NF-κB p105 (precursor of NF-κB p50 sub-unit) (supplemental Fig. 2B). The results indicate that decreased NF-κB expression leads to increased sensitivity to gemcitabine (Fig. 4A) correlated to an increased of Bax/BclXL ratio (Fig. 4B). On the contrary, decreased Erk1/2 and JNK expression led to a decreased sensitivity to gemcitabine (Fig. 4A) correlated to a decreased Bax/BclXL ratio (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that targeting NF-κB pathway appears more appropriate if one wants to alter cell sensitivity to gemcitabine.

Figure 4. Inhibition of NF-κB pathway sensitizes CAPAN-2 cells to gemcitabine.

(A) Cell survival rate was measured following Erk1/2, JNK and NF-κB inhibition in CAPAN-2 cells using specific siRNA during 48h before gemcitabine treatment (100 nM). Sensitivity to gemcitabine was compared to a non-targeting siRNA (siControl). (B) Apoptotic markers Bax and BclXL expression was measured by western-blotting. Density of each band was measured and Bax/BclXL ratio calculated where siControl ratio was arbitrarily set to 1.

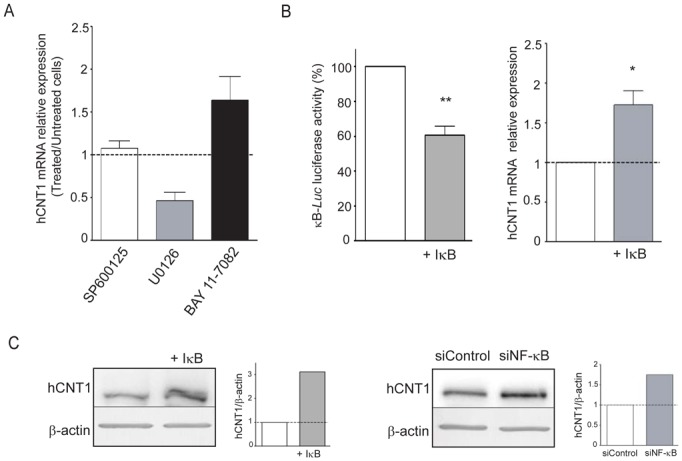

The NF-κB pathway regulates hCNT1 expression

hCNT1 mRNA expression was measured by qRT-PCR after CAPAN-2 cell treatment with specific pharmacological inhibitors of MAPK (U0126), JNK (SP600125) and NF-κB (BAY-11-7082) pathways (Fig. 5A). The results indicate that inhibition of MAPK leads to decreased hCNT1 mRNA expression (two-fold), whereas treatment with NF-κB inhibitor induced increased of hCNT1 mRNA level (1.5-fold). No modification of hCNT1 mRNA level was observed following treatment with JNK pathway inhibitor. To confirm the implication of the NF-κB pathway on hCNT1 regulation, the inhibitor of kappa B (IκB), was overexpressed in both CAPAN-2 and CAPAN-1 cells and hCNT1 mRNA level was measured (Fig. 5B and supplemental Fig. 3C). Decreased activity of NF-κB using the synthetic κB-Luc promoter confirmed the efficiency of IκB. Similarly to pharmacological inhibition, overexpression of IκB increased hCNT1 mRNA expression (Fig. 5B). Increased hCNT1 expression at the protein level was then confirmed either after IκB overexpression or transfection of NF-κB p105 siRNA (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results clearly show that the NF-κB pathway negatively regulates hCNT1 expression.

Figure 5. Identification of the NF-κB pathway as a regulator of hCNT1 expression.

(A) CAPAN-2 cells were treated for 24h with pharmacological inhibitor of MAPK (U0126, 10 μM), JNK (SP600125, 10 μM) or NF-κB (BAY-11-7082, 10 μM) pathways. hCNT1 mRNA expression level was measured by qRT-PCR. The histogram represents the ratio between treated/untreated cells against the inhibitor. The results are means that represent three separate experiments in triplicate for each inhibitor. (B) Overexpression of IκB in CAPAN-2 cells was performed by co-transfecting pCR3-IκB or pCR3 empty vector for 48h in the presence of the κB-Luc synthetic promoter. RNA or protein extraction was then carried out. Data are represented as histograms. (C) Western-blot of hCNT1 was performed after inhibition of NF-κB pathway with a specific siRNA or by IκB overexpression with pCR3-IκB in CAPAN-2 cells.

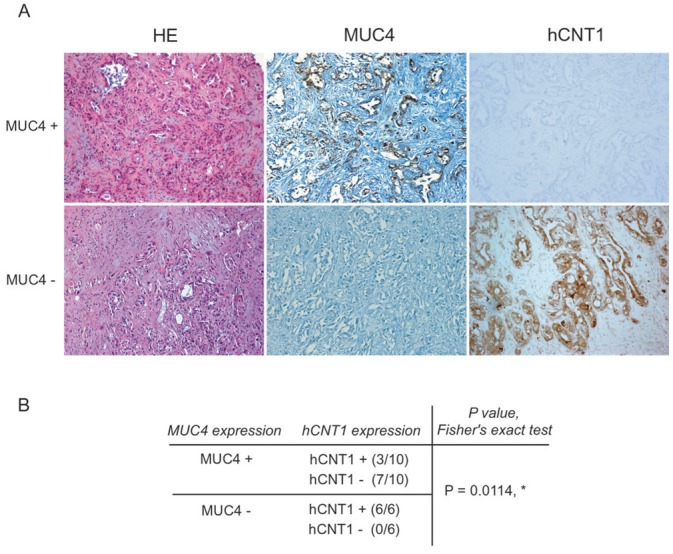

MUC4 expression is conversely correlated to hCNT1 in tissues from patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Having shown in vitro that MUC4 expression is correlated with a decreased expression of hCNT1 in pancreatic cancer cells, we undertook to study their expression on a small population of tissues from 16 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Immunohistochemical stainings show that MUC4 was expressed in 10/16 PC samples and hCNT1 expressed in 9/16 PC tumors. In MUC4 positive tumors, 7/10 patients did not express hCNT1. Interestingly, 100% of the samples not expressing MUC4 were positive for hCNT1 (6/6), suggesting a converse expression of MUC4 and hCNT1. Moreover, Fisher’s exact test indicated that proportions differed significantly (p=0.0114).

Discussion

A major and dramatic characteristic of pancreatic adenocarcinoma is the high resistance to chemotherapy leading to low efficiency of therapies, in particular those based on gemcitabine. The understanding of mechanisms underlying chemoresistance is thus mandatory if one wants to identify new predictive and/or prognostic markers and develop new therapeutic approches. In this study we show that the MUC4 mucin is involved in pancreatic cancer cell chemoresistance to gemcitabine via two complementary mechanisms involving apoptosis repression for one and nucleoside transporter hCNT1 inhibition via the NF-κB pathway for the other.

Neo-expression of MUC4 in the early steps of pancreatic carcinogenesis suggests that this membrane-bound mucin is implicated in the acquisition of an aggressive phenotype by tumors (23) and as such has been proposed as a new biomarker. Several in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that MUC4 modulate tumor growth, invasion, adherence and apoptosis (14, 16–18). Very recently, we have also shown that the PC cells lacking MUC4 were less proliferative with decreased cyclin D1 expression and G1 cell cycle arrest (15). Altogether, these alterations could potentially confer chemoresistance capacity to tumor cells.

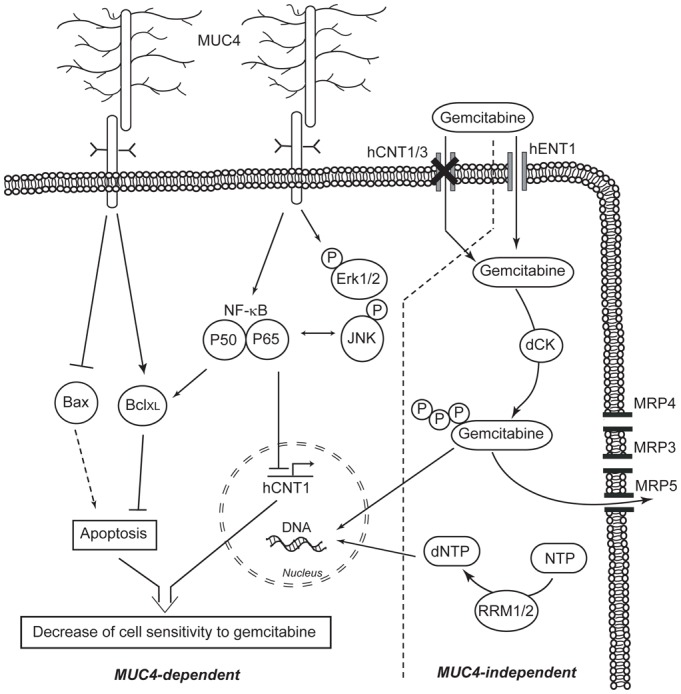

Based on these observations, Bafna et al. have shown that MUC4 expression in CD18/HPAF pancreatic cancer cell line decreases Bad pro-apoptotic activity by its phophorylation via Erk1/2 kinase, thereby decreasing gemcitabine cytotoxicity (10). In this report, we show that the loss of MUC4 is sufficient to modify Bax (pro-apoptotic) and BclXL (anti-apoptotic) expression, leading to an increase of Bax/BclXL ratio, indicating an increase in susceptibility to apoptosis. The importance of the Bax/BclXL ratio is attested by the fact that it is associated in prostate (24), breast (25) and pancreatic cancers (26) with chemotherapeutic sensitivity and has been proposed as a predictive marker. In our cellular models, the regulation of Bax and BclXL by MUC4 seems in part to be mediated by the NF-κB pathway and not by Erk1/2 and JNK pathways (Fig. 7). Our results are thus in favor of a role for MUC4 as an apoptosis regulator that would influence PC cell resistance to gemcitabine.

Figure 7. Schematic representation of the proposed mechanisms of pancreatic cancer cell chemosensitivity to gemcitabine.

Left panel: MUC4-dependent mechanisms involving either decrease of hCNT1 nucleoside transporter expression via the NF-κB pathway or modification of the Bax/BclXL ratio (up-regulation of BclXL and down-regulation of Bax expression). Right panel: MUC4-independent mechanisms. MRP4 channel increases cell sensitivity to gemcitabine by an unknown mechanism while MRP3 is not involved. MRP5 is known to decrease cell sensitivity to gemcitabine as well as modification of deoxycytidine kinase (dCK) and ribonucleotide reductase (RRM1/2) (20, 22, 32).

However, gemcitabine cytotoxic effect can not be optimal in absence of an efficient metabolism pathway to take up the drug. This is especially true for resistant tumor cells that often exhibit an altered metabolism of gemcitabine. In this study, absence of MUC4 in PC cells led to a dramatic modification in hCNT1 and hCNT3 transporters as well as MRP3 and MRP4 drug-detoxifying channels expression levels. We also show that hCNT1, hCNT3 and MRP4 are involved in gemcitabine sensitivity. MRP channels are able to export out of the cell a wide range of lipophilic anions such as chemotherapeutic drugs in order to maintain a drug resistant phenotype. Overexpression of MRP3 was found in several cancers such as ovarian (27), lung (28) and pancreatic cancers (29). MRP3 overexpression was correlated to cell chemoresistance to several drugs such as methotrexate, etoposide, doxorubicin and platinum agents. Nevertheless, in these studies MRP3 was not implicated in nucleoside-derived drug resistance. In our work, MRP3 was also not an actor of drug resistance as opposed to MRP4. Like MRP5 and MRP8, MRP4 is able to transport cyclic nucleotides out of the cell and was previously shown to confer cell chemoresistance to 6-mercaptopurine and 6-thioguanine in leukemia (30) as well as to methotrexate (31). While the implication of MRP5 in 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and gemcitabine resistance was demonstrated (32), the role of MRP4 remains unclear. In this work, we show that MRP4 expression is conversely correlated to gemcitabine resistance making this channel a potential interesting marker that is independent of MUC4 expression (Fig. 7). A similar result has been previously described where resistance to several drugs in melanoma cells by Muc4 expression, was conversely correlated to MDR1 and MRP1, that are members of multidrug resistance family (33). We thus propose that MRP4 acts independently of MUC4 to convey gemcitabine sensitivity.

Interestingly, hCNT1 is up-regulated when MUC4 is inhibited and this is correlated to drug sensitivity. The same result was found for hCNT3. This correlation was observed in both CAPAN-1 and CAPAN-2 cells for hCNT1, but only in CAPAN-2 for hCNT3. This suggests a cell-specific mechanism for hCNT3. While in vitro studies have correlated hCNT1 expression with a drug-resistant phenotype of PC cells (8, 9), no significant evidence has proven in vivo implication with a correlation to a better patient outcome. Our in vitro and ex vivo data indicate that MUC4 and hCNT1 expression are conversely correlated in PC cells as well as in tumor samples from patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. These data confer to MUC4 a potential as a predictive marker and will have to be confirmed in bigger cohorts.

Investigation of hCNT1 regulation by MUC4 led us to show that the NF-κB pathway mediates this mechanism. The NF-κB pathway is well-known to be constitutively activated in PC compared to normal pancreas (34). NF-κB also promotes tumor progression by regulating genes implicated in proliferation, angiogenesis and survival. Implication of NF-κB pathway in chemoresistance to gemcitabine was already described and was found to modulate apoptosis (35). In our work, in addition to apoptotic regulation, we highlight a new resistance mechanism mediated by the NF-κB pathway that leads to the down-regulation of hCNT1 thereby decreasing gemcitabine uptake and efficiency (Fig. 7). Our results support the promising current effort to improve gemcitabine efficacy by targeting the NF-κB pathway with natural (36, 37) or chemical (38) inhibitors or by siRNA delivery (39).

We have described in this paper, two complementary resistance mechanisms of PC cells to gemcitabine that are linked to MUC4. They are mediated by the NF-κB pathway and lead to (i) the modulation of apoptosis and (ii) the regulation of hCNT1 transporter expression. These data reinforce the value of MUC4 as a prognostic marker. Interestingly, cell sensitivity to cytarabine/aracytin® (ARA-C), another cytidine analog, mainly used in leukemia or lymphoma, but that is incorporated into human DNA via a similar metabolic pathway as gemcitabine, was also altered in MUC4-KD cells. This suggests that our findings regarding MUC4 role in drug resistance could be extended to other nucleoside analogs and other types of cancer. FOLFIRINOX, a new therapeutic protocol which combines therapeutic agents (5-FU, irinotecan, oxaliplatin and leucovorin), brings hope since statistical and clinical significant benefit compared to gemcitabine alone was reported in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (40). Interestingly, 5-FU was shown to induce MRP3 expression increasing oxaliplatin efficiency (41) whereas MRP4 expression increases irinotecan resistance (42). In preliminary experiments, we have also found that the loss of MUC4 leads to an increased sensitivity of CAPAN-2 cells to 5-FU (personal communication). Taken into account these recent data and ours, targeting MUC4 would certainly improve efficiency of the FOLFIRINOX protocol and is at this time under investigation.

Material & Methods

Cell culture

CAPAN-1 and CAPAN-2 PC cell lines were cultured as previously described (43). MUC4 knocked-down (MUC4-KD) cells were obtained by stable transfection with pRetroSuper plasmid (SA Biosciences™ Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) containing a small hairpin RNA targeting MUC4 (5′-AAGTGGAACGAATCGATTCTGTTCAAGAGACAGAATCGATTCGTTCCACTT-3′). Control cells (Mock) were obtained by transfecting the empty-vector pRetroSuper plasmid. After selection with neomycine (300 μg/ml) and serial limit dilution, expression of MUC4 was controlled by western-blotting. Four selected clones of Mock and MUC4-KD cells were pooled in order to avoid clonal variation. All cells were maintained in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 and cultured as the parental cells. Pharmacological inhibitors were added to the cells for 24h, at the following final concentrations: U0126 (10 μM, inhibitor of MAPK, Calbiochem, Merck Chemical Limited, Nottingham, United Kingdom), SP600125 (10 μM, inhibitor of JNK, Calbiochem) and BAY-11-7082 (10 μM, inhibitor of NF-κB, Calbiochem).

Protein extraction

Cytosolic, nuclear and total cellular extracts were performed as previously described in Van Seuningen et al.(44) and Jonckheere et al.(45), respectively.

Western-blotting

Western-blotting on nitrocellulose membrane (0.2 μm, Whatman) was carried out as previously described (46). Membranes were incubated with antibodies against phospho- Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (clone 20G11, 1/500), Erk1/2 (clone I37F5, 1/500), NF-κB Phospho-p65 (Ser536) (clone 93H1, 1/500), NF-κB p65 (clone E498, 1/500), phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) (9251, dilution 1/500), SAPK/JNK (clone 56G8, 1/500), phospho-p53 (Ser 15) (9284, dilution 1/500), p53 (9282, 1/500), from Cell Signaling Technology (Ozyme, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France); Bax (clone N-20, 1/500), BclXL (clone H-5, 1/500), hCNT1 (clone H-70, 1/200), MRP3 (clone H-16, 1/200), MRP4 (clone M4I-10, 1/200), MUC4 (clone 8G7, 1/500), NF-κB p50 (clone H-119, 1/500), Sp1 (PEP2, 1/1000) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Heidlberg, Germany) or hCNT3 (HPA023311; 1/500), tubulin (DM1A, 1/1000) and β-actin (A5441, 1/5000) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Quentin Fallavier, France). Antibodies were diluted in 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in Tris-Buffered Saline Tween-20 (TBS-T), except for MUC4 and β-actin diluted in TBS-T, and incubated overnight at 4°C. Peroxydase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) were used and immunoreactive bands were visualised using the West Pico chemoluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific, Pierce, Brebières, France). Chemo-luminescence was visualised using LAS4000 apparatus (Fujifilm). Density of bands were integrated using Gel analyst software® (Claravision, Paris, France) and represented as histograms. Three independent experiments were performed.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cells were seeded in growth medium into 96-well plates at a density of 104 cells per well. After 24h incubation, the medium was replaced by fresh medium containing gemcitabine, oxaliplatin or ARA-C at the determined concentration (range: 10 nM-20 μM) and incubated for 72h at 37°C. The viability of cells was determined using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich). Yellow colored MTT was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Villeban sur Yvette, France) at a final concentration of 5 mg/ml. The cells were then incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37°C for 1h. Formazan cristal was solubilised in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich) for 5 min at room temperature before analyzed spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 570 nm with a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). Percentage of viability = [(Atreated − Ablank)/(Aneg. − Ablank)] × 100; where Atreated is the average of absorbance in wells containing cells treated with gemcitabine, Aneg. is the average of wells containing cells without gemcitabine treatment, and Ablank is the average of wells containing medium without cells.

RNA Interference

Transient inhibition of MRP3, MRP4, hCNT1 and hCNT3 was performed using a pool of siRNA designed by Santa Cruz Biotechnology with Effectene® (Qiagen) following manufacturer’s instruction. Transient KD for Erk1 (MAPK1), Erk2 (MAPK3), JNK1 (MAPK8), JNK2 (MAPK9) and NF-κB (p105 NF-κB) was performed using siRNA from Dharmacon (Thermo Scientific) following the protocol described previously (46). Controls were performed using a Non-Targeting siRNA (NT) in both protocols. Cells were seeded at a density of 5x105 cells per well into 6-well plates for RNA and protein extraction, or at a density of 104 cells per well into 96-well plates for cytotoxic assay, and left for 48h at 37°C before gemcitabine treatement (100 nM) for another 24h at 37°C.

Luciferase activity

Transfection of κB-Luc synthetic promoter containing three κB binding sites was performed with Effectene® (Qiagen). Total cell extracts were prepared after 48h incubation at 37°C using 1X Reagent Lysis Buffer (Promega, Charbonniere-les-Bains, France). Luciferase activity in the extracts (20 μl) was measured on a Mithras Microplate Reader LB 940 (Berthold Technologies, Thoiry, France). Total protein content in the extract (4 μl) was measured using the bicinchoninic acid method in 96-well plates (Pierce, Thermoscientific). Relative luciferase activity was expressed as fold activation of the κB-Luc vector compared to that with the empty vector pGL3 basic (Promega). In co-transfection studies, pCR3-IκB or pCR3 empty vector was transfected with κB-Luc vector. Each experiment was assayed in triplicate in at least three independent experiments.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA from PC cells was prepared using the NucleoSpin® RNA II kit (Macherey Nagel, Hoerdt, Germany). cDNA was prepared as previously described (47). PCR was performed using SsoFast™ Evagreen Supermix kit following the manufacturer’s protocol using the CFX96 real time PCR system (Bio-Rad). Primer information is given in table 1. Each marker was assayed in triplicate in three independent experiments. Expression levels of genes of interest were normalized to the mRNA level of GAPDH housekeeping gene.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for quantitative real-time RT-PCR

| Gene | Forward Primer 5′ to 3′ | Reverse Primer 5′ to 3′ | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCK | GAGAAACCTGAACGATGGTCTT | TCTCTGCATCTTTGAGCTTGC | 102 |

| hENT1 | CTCTCAGCCCACCAATGAAAG | CTCAACAGTCACGGCTGGAA | 123 |

| hCNT1 | CCTCACCTGTGTGGTCCTCA | AGACCCCTCTTAAACCAGAGC | 86 |

| hCNT3 | CTTTTCTGGAGTACACAGATGCT | CGGCAGGACCTTAAATGCAAA | 108 |

| RRM1 | CTGCAACCTTGACTACTAAGCA | CTTCCATCACATCACTGAACACT | 108 |

| RRM2 | CCACGGAGCCGAAAACTAAAG | CTCTGCCTTCTTATACATCTGCC | 131 |

| MRP3 | GGAGGACATTTGGTGGGCTTT | CCCTCTGAGCACTGGAAGTC | 90 |

| MRP4 | AAGTGAACAACCTCCAGTTCCAG | GGCTCTCCAGAGCACCATCT | 119 |

| MRP5 | AGAACTCGACCGTTGGAATGC | TCATCCAGGATTCTGAGCTGAG | 104 |

| GAPDH | CCACATCGCTCAGACACCAT | CCAGGCGCCCAATACG | 70 |

Flow Cytometry

Cells were plated into 6-well plates at a density of 1.5x105 cells per well and incubated for 24h at 37°C before gemcitabine treatment for another 72h. Apoptosis was measured by Annexin V-PE (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed twice with 1X PBS and 1x105 cells of each condition were incubated with 5 μl of annexin V-PE (50 μg/ml) and 10 μl propidium iodide (100 μg/ml) for 10 min at room temperature. Staining intensity was determined with Cell Lab Quanta™ SC MPL (Beckman Coulter, Roissy, France) and analyzed with Quanta-Collection.

Immunohistochemical analyses

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma samples were obtained from 16 patients of the Lille University Hospital. No patient received either chemotherapy or radiotherapy before the surgical resection. A consent form was obtained from each patient, and permission for removal of surgical samples was obtained from the institutional review board. Patient characteristics are given in table 2. Samples were processed for paraffin embedding. Tissue sections (4 μm) were stained with Hematoxylin Eosin. Manual hCNT1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) was carried out as described in Van der Sluis et al. (48) and automatic MUC4 IHC with an automated immunostainer (ES, Ventana Medical System, Strasbourg, France) as in Mariette et al. (49). hCNT1 (H-70, 1/100) and MUC4 (8G7, 1/100) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Sections were counterstained with haematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted. A positive control for MUC4 and hCNT1 immunostainings and a negative control in absence of primary antibody were included in each set of experiments.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

| Patient | Age (years) | Gender | Metastatic site | Location of tumor in pancreas | Tumor differentiation | TNM stage | MUC4 | hCNT1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65 | F | liver | NS | M | pTxNxM1 | + | − |

| 2 | 63 | F | liver | head | M | pTxNxM1 | + | + |

| 3 | 46 | M | head | M | pT3N1M0 | − | + | |

| 4 | 51 | M | liver, bone | NS | M | pTxNxM1 | − | + |

| 5 | 61 | M | peritoneum | tail | M | pT3N1M1 | + | − |

| 6 | 57 | F | peritoneum, ovary | NS | W | pT4NxM1 | + | + |

| 7 | 57 | F | peritoneum | head | M | pTxNxM1 | + | − |

| 8 | 51 | M | liver | NS | W | pTxNxM1 | + | − |

| 9 | 54 | M | peritoneum | head | W | pTxNxM1 | − | + |

| 10 | 60 | M | liver, peritoneum | head | M | pTxN1M1 | + | + |

| 11 | 78 | F | head | P | pTxNxM0 | + | − | |

| 12 | 61 | F | NS | M | pT3NxM0 | − | + | |

| 13 | 47 | F | NS | M | pTxN1M0 | + | − | |

| 14 | 66 | M | NS | M | pTxN0M0 | − | + | |

| 15 | 53 | M | head | M | pTxN1M0 | + | − | |

| 16 | 73 | F | head | M | pT3N1M0 | − | + |

M, moderately differentiated. W, well-differentiated. P, poorly-differentiated. NS, not specified.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using the Graphpad Prism 4.0 software (Graphpad softwares Inc., La Jolla, USA). Differences in data of two samples were analysed by the student’s t test or ANOVA test with selected comparision using tukey post-hoc test and were considered significant for P-values <0.05 *, p<0.01 ** or p<0.001 ***. IHC results were compared using the Fisher’s exact test.

Figure 6. MUC4 and hCNT1 expression is conversely correlated in tissues from patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

(A) MUC4 and hCNT1 expression was analysed by immunohistochemistry. MUC4+ indicates a tissue sample positive for MUC4 and negative for hCNT1. MUC4- indicates a tissue sample that does not express MUC4 but is positive for hCNT1. Histological sections were stained with Hematoxylin Eosin (HE). Magnification (x20). (B) MUC4 expression is correlated with a lack of expression of hCNT1. Fisher’s exact test indicates that proportions differ significantly (p=0.0114, *)

Acknowledgments

We thank M.H. Gevaert and R. Siminsky (Department of Histology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Lille 2) and the technical platform IFR114/IMPRT for flow cytometry (Dr N Jouy) and luciferase (A.S Drucbert) analyses. Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin are a kind gift of Dr A Lansiaux (Centre Oscar Lambret, Université Lille Nord de France, Inserm UMR837, team 4, Lille, France). Cytarabine/aracytin® ARA-C is a kind gift of Pr B Quesnel (Oncohaematology department, Centre Hospitalier Régional et Universitaire de Lille, Inserm UMR837, team 3, Lille, France). We thank Dr J.L. Desseyn (Inserm U995) for his help in designing MUC4 shRNA. Nicolas Skrypek is a recipient of a PhD fellowship of Centre Hospitalier Régional et Universitaire (CHRU) de Lille and Région Nord-Pas de Calais. Dr Nicolas Jonckheere is a recipient of postdoctoral fellowship from the Institut National du Cancer (INCa) and Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (LNCC). This work is supported by a grant from la Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (Equipe Labellisée Ligue 2010, IVS). Isabelle Van Seuningen is the recipient of a “Contrat Hospitalier de Recherche Translationnelle”/CHRT 2010, AVIESAN.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent A, Herman J, Schulick R, Hruban RH, Goggins M. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2011;378(9791):607–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62307-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Reilly EM. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma: new strategies for success. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2009;3(2 Suppl):S11–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damaraju VL, Damaraju S, Young JD, Baldwin SA, Mackey J, Sawyer MB, et al. Nucleoside anticancer drugs: the role of nucleoside transporters in resistance to cancer chemotherapy. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7524–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrell JJ, Elsaleh H, Garcia M, Lai R, Ammar A, Regine WF, et al. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 levels predict response to gemcitabine in patients with pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(1):187–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giovannetti E, Del Tacca M, Mey V, Funel N, Nannizzi S, Ricci S, et al. Transcription analysis of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter-1 predicts survival in pancreas cancer patients treated with gemcitabine. Cancer Res. 2006;66(7):3928–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marechal R, Mackey JR, Lai R, Demetter P, Peeters M, Polus M, et al. Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 and human concentrative nucleoside transporter 3 predict survival after adjuvant gemcitabine therapy in resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(8):2913–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhutia YD, Hung SW, Patel B, Lovin D, Govindarajan R. CNT1 expression influences proliferation and chemosensitivity in drug-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71(5):1825–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Manteiga J, Molina-Arcas M, Casado FJ, Mazo A, Pastor-Anglada M. Nucleoside transporter profiles in human pancreatic cancer cells: role of hCNT1 in 2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine- induced cytotoxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(13):5000–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bafna S, Kaur S, Momi N, Batra SK. Pancreatic cancer cells resistance to gemcitabine: the role of MUC4 mucin. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(7):1155–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalra AV, Campbell RB. Mucin impedes cytotoxic effect of 5-FU against growth of human pancreatic cancer cells: overcoming cellular barriers for therapeutic gain. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(7):910–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalra AV, Campbell RB. Mucin overexpression limits the effectiveness of 5-FU by reducing intracellular drug uptake and antineoplastic drug effects in pancreatic tumours. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(1):164–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonckheere N, Skrypek N, van Seuningen I. Mucins and pancreatic cancer. Cancers. 2010;2(4):1794–1812. doi: 10.3390/cancers2041794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaturvedi P, Singh AP, Moniaux N, Senapati S, Chakraborty S, Meza JL, et al. MUC4 mucin potentiates pancreatic tumor cell proliferation, survival, and invasive properties and interferes with its interaction to extracellular matrix proteins. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5(4):309–20. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonckheere N, Skrypek N, Merlin J, Dessein AF, Dumont P, Leteurtre E, et al. The Mucin MUC4 and Its Membrane Partner ErbB2 Regulate Biological Properties of Human CAPAN-2 Pancreatic Cancer Cells via Different Signalling Pathways. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komatsu M, Tatum L, Altman NH, Carothers Carraway CA, Carraway KL. Potentiation of metastasis by cell surface sialomucin complex (rat MUC4), a multifunctional anti-adhesive glycoprotein. Int J Cancer. 2000;87(4):480–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000815)87:4<480::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponnusamy MP, Lakshmanan I, Jain M, Das S, Chakraborty S, Dey P, et al. MUC4 mucin-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition: a novel mechanism for metastasis of human ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2010;29(42):5741–54. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Workman HC, Sweeney C, Carraway KL., 3rd The membrane mucin Muc4 inhibits apoptosis induced by multiple insults via ErbB2-dependent and ErbB2-independent mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2009;69(7):2845–52. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blackstock AW, Lightfoot H, Case LD, Tepper JE, Mukherji SK, Mitchell BS, et al. Tumor uptake and elimination of 2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxycytidine (gemcitabine) after deoxycytidine kinase gene transfer: correlation with in vivo tumor response. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(10):3263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marechal R, Mackey JR, Lai R, Demetter P, Peeters M, Polus M, et al. Deoxycitidine kinase is associated with prolonged survival after adjuvant gemcitabine for resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116(22):5200–6. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kruh GD, Belinsky MG. The MRP family of drug efflux pumps. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7537–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordheim LP, Seve P, Tredan O, Dumontet C. The ribonucleotide reductase large subunit (RRM1) as a predictive factor in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2010;12(7):693–702. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swartz MJ, Batra SK, Varshney GC, Hollingsworth MA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. MUC4 expression increases progressively in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117(5):791–6. doi: 10.1309/7Y7N-M1WM-R0YK-M2VA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackey TJ, Borkowski A, Amin P, Jacobs SC, Kyprianou N. bcl-2/bax ratio as a predictive marker for therapeutic response to radiotherapy in patients with prostate cancer. Urology. 1998;52(6):1085–90. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Turner BC, Pratt C, Howard B, Zapata JM, et al. Prognostic significance of apoptosis regulators in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6(1):29–40. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi X, Liu S, Kleeff J, Friess H, Buchler MW. Acquired resistance of pancreatic cancer cells towards 5-Fluorouracil and gemcitabine is associated with altered expression of apoptosis-regulating genes. Oncology. 2002;62(4):354–62. doi: 10.1159/000065068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohishi Y, Oda Y, Uchiumi T, Kobayashi H, Hirakawa T, Miyamoto S, et al. ATP-binding cassette superfamily transporter gene expression in human primary ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(12):3767–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oguri T, Isobe T, Fujitaka K, Ishikawa N, Kohno N. Association between expression of the MRP3 gene and exposure to platinum drugs in lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2001;93(4):584–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konig J, Hartel M, Nies AT, Martignoni ME, Guo J, Buchler MW, et al. Expression and localization of human multidrug resistance protein (ABCC) family members in pancreatic carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2005;115(3):359–67. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen ZS, Lee K, Kruh GD. Transport of cyclic nucleotides and estradiol 17-beta-D-glucuronide by multidrug resistance protein 4. Resistance to 6-mercaptopurine and 6-thioguanine. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(36):33747–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104833200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee K, Klein-Szanto AJ, Kruh GD. Analysis of the MRP4 drug resistance profile in transfected NIH3T3 cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(23):1934–40. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagmann W, Jesnowski R, Lohr JM. Interdependence of gemcitabine treatment, transporter expression, and resistance in human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Neoplasia. 2010;12(9):740–7. doi: 10.1593/neo.10576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu YP, Haq B, Carraway KL, Savaraj N, Lampidis TJ. Multidrug resistance correlates with overexpression of Muc4 but inversely with P-glycoprotein and multidrug resistance related protein in transfected human melanoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65(9):1419–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W, Abbruzzese JL, Evans DB, Larry L, Cleary KR, Chiao PJ. The nuclear factor-kappa B RelA transcription factor is constitutively activated in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5(1):119–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arlt A, Gehrz A, Muerkoster S, Vorndamm J, Kruse ML, Folsch UR, et al. Role of NF-kappaB and Akt/PI3K in the resistance of pancreatic carcinoma cell lines against gemcitabine-induced cell death. Oncogene. 2003;22(21):3243–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banerjee S, Zhang Y, Ali S, Bhuiyan M, Wang Z, Chiao PJ, et al. Molecular evidence for increased antitumor activity of gemcitabine by genistein in vitro and in vivo using an orthotopic model of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(19):9064–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kunnumakkara AB, Guha S, Krishnan S, Diagaradjane P, Gelovani J, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin potentiates antitumor activity of gemcitabine in an orthotopic model of pancreatic cancer through suppression of proliferation, angiogenesis, and inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB-regulated gene products. Cancer Res. 2007;67(8):3853–61. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang SJ, Gao Y, Chen H, Kong R, Jiang HC, Pan SH, et al. Dihydroartemisinin inactivates NF-kappaB and potentiates the anti-tumor effect of gemcitabine on pancreatic cancer both in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2010;293(1):99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong R, Sun B, Jiang H, Pan S, Chen H, Wang S, et al. Downregulation of nuclear factor-kappaB p65 subunit by small interfering RNA synergizes with gemcitabine to inhibit the growth of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2010;291(1):90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Theile D, Grebhardt S, Haefeli WE, Weiss J. Involvement of drug transporters in the synergistic action of FOLFOX combination chemotherapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78(11):1366–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian Q, Zhang J, Tan TM, Chan E, Duan W, Chan SY, et al. Human multidrug resistance associated protein 4 confers resistance to camptothecins. Pharm Res. 2005;22(11):1837–53. doi: 10.1007/s11095-005-7595-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jonckheere N, Perrais M, Mariette C, Batra SK, Aubert JP, Pigny P, et al. A role for human MUC4 mucin gene, the ErbB2 ligand, as a target of TGF-beta in pancreatic carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2004;23(34):5729–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Seuningen I, Ostrowski J, Bustelo XR, Sleath PR, Bomsztyk K. The K protein domain that recruits the interleukin 1-responsive K protein kinase lies adjacent to a cluster of c-Src and Vav SH3-binding sites. Implications that K protein acts as a docking platform. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(45):26976–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jonckheere N, Fauquette V, Stechly L, Saint-Laurent N, Aubert S, Susini C, et al. Tumour growth and resistance to gemcitabine of pancreatic cancer cells are decreased by AP-2alpha overexpression. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(4):637–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piessen G, Jonckheere N, Vincent A, Hemon B, Ducourouble MP, Copin MC, et al. Regulation of the human mucin MUC4 by taurodeoxycholic and taurochenodeoxycholic bile acids in oesophageal cancer cells is mediated by hepatocyte nuclear factor 1alpha. Biochem J. 2007;402(1):81–91. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Seuningen I, Perrais M, Pigny P, Porchet N, Aubert JP. Sequence of the 5′-flanking region and promoter activity of the human mucin gene MUC5B in different phenotypes of colon cancer cells. Biochem J. 2000;348(Pt 3):675–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Sluis M, Melis MH, Jonckheere N, Ducourouble MP, Buller HA, Renes I, et al. The murine Muc2 mucin gene is transcriptionally regulated by the zinc-finger GATA-4 transcription factor in intestinal cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;325(3):952–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mariette C, Perrais M, Leteurtre E, Jonckheere N, Hemon B, Pigny P, et al. Transcriptional regulation of human mucin MUC4 by bile acids in oesophageal cancer cells is promoter-dependent and involves activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signalling pathway. Biochem J. 2004;377(Pt 3):701–8. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]