Abstract

Objective To introduce and illustrate recent advances in statistical approaches to simultaneous modeling of multiple change processes. Methods Provide a general overview of how to use structural equations to simultaneously model multiple change processes and illustrate the use of a theoretical model of change to guide selection of an appropriate specification from competing alternatives. The selected latent change score model is then fit to data collected during an adolescent weight-control treatment trial. Results A latent change score model is built starting with the foundation of repeated-measures analysis of variance and illustrated using graphical notation. Conclusions The assumptions behind using structural equations to model change are discussed as well as limitations of the approach. Practical guidance is provided on matching the statistical model to the theory underlying the observed change processes and the research question(s) being answered by the analyses.

Keywords: autoregressive modeling, growth curve modeling, latent change score, latent curve analysis, structural equation models

Structural equation modeling (SEM) provides a framework for flexibly modeling multiple change processes. Using structural equations, researchers can specify a model of change that closely matches their substantive theories of how processes change and influence each other across time. Structural equations have been used for some time to specify or define latent curve models, where the components of the change trajectory (e.g., intercept, slope, quadratic, etc.) are represented by latent (a.k.a., random) variables that allow these components to vary across individuals. There are, however, many types of change models that can be specified using structural equations. The most common are latent growth curve (LGC) models (Curran, Obeidat, & Losardo, 2010), but there are others, including latent change score (LCS) models (McArdle, 2009), autoregressive latent trajectory (ALT) models (Bollen & Curran, 2004), trait–state models for longitudinal data (Kenny & Zautra, 2001), piecewise latent trajectory models (Flora, 2008), and cross-lagged autoregressive models (Little, Preacher, Selig, & Card, 2007). Moreover, each of these specifications can be modified to better reflect the investigators’ theory about how the processes change over time.

The increasing number of possible specifications allows researchers to tailor their statistical model to answer their particular research question, but deciding on an approach that will provide an appropriate test of the hypothesis can be daunting. There is not currently a “one-size-fits-all” model, and selecting the most appropriate specification depends on the research question and the nature of the processes being studied. Access to an increasing number of possible specifications also increases the danger of post hoc selection, where researchers explore multiple statistical models and select the one that best supports the stated hypotheses instead of the one that most accurately reflects the processes being studied. Strong theory about how the processes being investigated influence each other across time helps guide the selection of the most appropriate specification for the research question, and helps protect against post hoc model selection (Collins, 2006). However, using theory to inform the statistical model is easier said than done.

The aim of this article is to help researchers in pediatric psychology better understand the assumptions and implications behind two different statistical models of change. This aim will be accomplished by articulating our theoretical model of how the variables of interest change and are associated over time, selecting an appropriate statistical model of change, applying it to clinical data, and interpreting the results. The data we will use throughout the manuscript were obtained during an adolescent weight-control treatment trial (Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2012). Participants were randomized to a behavioral weight-control program with either aerobic activity or peer-enhanced physical activity. Participants and their parents attended 16 weeks of group treatment, followed by 4 bi-weekly weight-control maintenance sessions. Assessments were conducted at baseline and at 4, 12, and 24 months post-randomization. Participants were 118 adolescents aged 13–16 years with a mean body mass index of 31.4. At each of the four time points, participants completed the 8-item Fear of Negative Evaluation (FNE) subscale of the Society Anxiety Scale–Adolescent (La Greca & Lopez, 1998), and height and weight were measured by trained research assistants. The FNE subscale is a measure of the degree to which adolescents are concerned with how others evaluate them. Each item was rated on a 5-point scale from 1 = not at all to 5 = all the time. Responses to the FNE items were summed, with high scores reflecting greater anxiety associated with perceived negative evaluations by others. Overweight status was defined as percent overweight—i.e., adolescents’ percent >50th percentile body mass index for age and sex (OW). Previous manuscripts reported significant decreases in weight for both treatment conditions, but no significant differences between conditions (Jelalian et al., 2010; Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2012). To simplify the presentation of these data, we will combine the two treatment conditions. However, the initial decrease in percent overweight between the first and second assessment (i.e., intervention effect) will have to be accounted for by the statistical model and will play a role in which model we ultimately select.

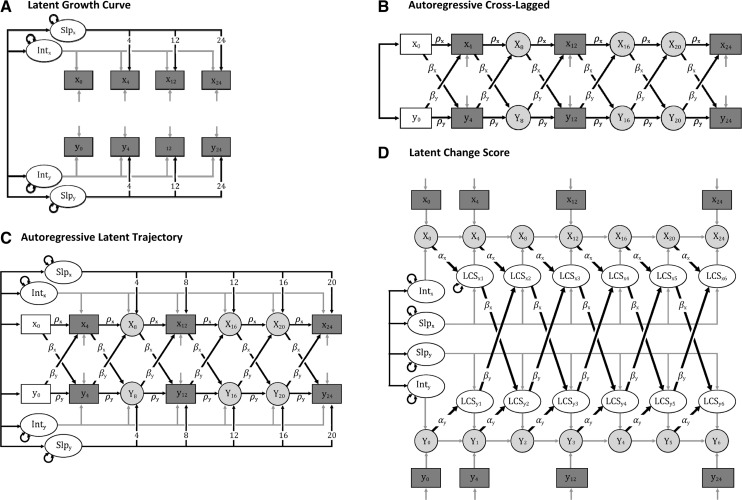

Our hypotheses are focused on the interplay between FNE and OW. Specifically, we hypothesize that change in OW will be reciprocally associated with change in FNE over time. There are a number of models that could be used to test this reciprocal relationship, including a multivariate or parallel-process LGC model, a cross-lagged autoregressive model, Bollen’s ALT model, and McArdle’s LCS model (Figure 1). In the next section, we will highlight the key assumptions and implications behind these models and settle on one that addresses our hypothesis while accounting for the features of the clinical trial from which the data were collected.

Figure 1.

Multivariate models. SLP = Slope; Int = Intercept; LCS = Latent Change Score; ρ = autoregressive parameter; β = cross-lagged parameters; α = proportional change parameters.

Notation

Throughout the article we will be using graphical notation to illustrate structural equations. In this notation, rectangles represent observed or measured variables, ovals represent latent or random variables, directed arrows represent regression parameters, and bidirectional arrows represent association parameters (e.g., correlations). Variances and residual variances (i.e., error terms) for latent variables are indicated by rounded double-headed arrows. Error terms for observed variables are often depicted as latent variables with a factor loading of “1”; for convenience and visual simplicity, we will use a small directed arrow to represent error terms of observed variables. Estimated parameters will be indicated by letters, and fixed parameters will be indicated by the number to which they were fixed. Parameters fixed to “0” are omitted from the representations, and due to their frequency, parameters fixed at “1” will be indicated using gray lines.

Articulating a Theoretical Model of Change

Our research question addresses the relationship between FNE and OW across time. We hypothesize that FNE and OW influence each other overtime, and will make the following assumptions about this bidirectional relationship: the relationship between FNE and OW does not change across the study period (i.e., from baseline to 24 months), the relationship between FNE and OW does not change across adolescence, and the relationship between FNE and OW is the same across individuals (i.e., there are no moderating influences for this relationship). Beyond the hypotheses about how FNE and OW relate to each other, there are additional hypotheses about how each process changes overtime. There is evidence suggesting that some of the change in FNE and OW can be attributed to development. It has been suggested that FNE increases across adolescence (Westenberg, Gullone, Bokhorst, Heyne, & King, 2007), and there is evidence that adolescents who are overweight increase in percent overweight across adolescence (Rooney, Mathiason, & Schauberger, 2011). We also expect that there will be variability among youth in the trajectories of FNE and OW across time. Beyond the contributions of maturation, there is evidence that FNE and percent overweight have some stability across time, meaning their current status is predicted by previous assessments, and that they are responsive to therapeutic intervention (Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2012).

Translating the Theory Into a Statistical Model

Selecting the Appropriate Specification

With a theory of how FNE and OW change and are associated over time, we can begin selecting from among the various statistical models of change. It is helpful to begin by considering simple models of change and moving to more complex models until the model matches the assertions of the hypothesized model of change. At the most basic, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (RMANOVA) can be used to model trajectories. This model allows participants to have different initial values (i.e., intercepts), but constrains the trajectories to be equal across participants. Our model of change assumes that the trajectories for OW and FNE vary across participants, making it a poor match to the assumptions of a RMANOVA. Additionally, the RMANOVA does not test for cross-lagged relationships, which eliminates the possibility of examining the bidirectional relationship between OW and FNE.

An LGC specification (Figure 1a) allows the trajectories to vary across participants, but does not separate sources of change. Our hypothesized model suggests that change in FNE and OW is the result of a number of processes, including developmental processes that are constant overtime (i.e., intercept and slope/trajectory), a stability process (i.e., levels of OW and FNE are predicted by their levels at a previous time point; a.k.a., autoregression), and the interplay of the associations between FNE and OW overtime. A multivariate or parallel-process LGC specification allows for tests of the association between constant growth parameters of OW and FNE (e.g., correlated intercepts, correlated slopes), but does not inform the direction of the association. In other words, LGC tests whether the developmental trajectories of OW and FNE are related, but not how they are related (e.g., does FNE predict change in OW, OW predict change in FNE, change in FNE predict change in OW, etc.). Compared with the RMANOVA, the LGC specification provides a better match with our hypothesized model of change. It does not, however, model all of the hypothesized change processes and may be overly simplistic for examining the interplay between FNE and OW across time.

A cross-lagged autoregressive specification (Figure 1b) provides the ability to evaluate how two processes may be associated across time; that is, whether change in FNE and change in OW are reciprocally related. It also provides the ability to include autoregressive parameters. With a cross-lagged model, it is possible to evaluate if the relationship between FNE and OW changes overtime, or if it changes as a result of an intervention. This is accomplished by allowing the cross-lagged parameters to vary across assessment points. The specification, however, does not model developmental trajectories (i.e., constant change). Compared with an LGC specification, a cross-lagged specification provides more flexibility in modeling the interplay between two change processes. However, because the cross-lagged model does not incorporate constant change trajectories, it also may be overly simplistic for modeling change processes that have developmental trajectories and, therefore, it does not match our hypothesized model.

Two advanced specifications have been developed to address some of the weaknesses of the LGC and cross-lagged specifications. The first is Bollen’s ALT model (Figure 1c), which combines the cross-lagged and LGC specifications. The second is McArdle’s LCS specification (Figure 1d), which divides the change processes into multiple segments and provides flexibility in modeling how change processes are associated over time. Because they both allow for the simultaneous modeling of multiple change processes (e.g., constant change, autoregressive) and because they model how change processes are associated across time (i.e., cross-lagged associations), both statistical models match our hypothesized model. There are important differences between these two specifications, which will inform which specification we will ultimately choose to answer the research question, but first, we would like to provide additional background about the ALT and LCS specifications.

Autoregressive Latent Trajectories

As we briefly mentioned, the ALT model combines the cross-lagged autoregressive and the LGC specifications. The ALT model estimates the associations among repeated measures as an additive combination of influences from an underlying growth trajectory and from the previous assessment. This is useful when testing child and adolescent developmental hypotheses where change may be due to both underlying growth processes, as well as may depend on the previous assessment. In terms of our study hypotheses, the ALT specification tests whether the longitudinal reciprocal associations between change in OW and change in FNE will be significant after accounting for previous measurements and individual developmental trajectories.

The ALT model is specified by regressing each assessment on the preceding assessment (i.e., autoregressive parameters) and on the preceding assessment from the linked process (i.e., cross-lagged parameters). The latent growth trajectory is included by defining a latent intercept term by fixing the factor loadings between the intercept term and each time point to 1, and by defining a latent slope term by fixing the factor loadings between the slope term and each time point to a series of numbers starting at 0 and increasing linearly according the spacing of each assessment (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 3 for evenly spaced assessments). Typically, the latent growth trajectory does not include the initial time point because the ALT model follows the tradition of autoregressive models where the initial time point is treated as predetermined, meaning that the statistical model does not attempt to explain or model the initial values. In our data, this means that the ALT model does not estimate participants’ initial levels of OW and FNE; instead, the initial raw values are used in the model. Treating the initial time point as predetermined requires that fewer assumptions are made when fitting the model to the data. This means the statistical model provides a closer fit to the observed data than with other approaches, like LCS models, that model the initial time points. However, not modeling the initial time points reduces the number of degrees of freedom available to model additional sources of change, such as treatment-related change.

The ALT specification accounts for the relationship among repeated assessments, but does not define the change between subsequent assessments as a parameter in the model. The data from the weight-control trial showed a decrease in FNE and OW for both treatment conditions between the first and second assessments. The ALT specification accounts for this decrease through the regression of the 4-month assessment on the baseline assessment and by including an intercept term for the 4-month assessment. However, the specification does not provide a direct estimate of this change, making it difficult to report the amount of change, predict individual variability in this change, or use the change to predict other outcomes.

Latent Change Scores

Change scores have had a controversial history (Cronbach & Furby, 1970; Williams & Zimmerman, 1996). One of the most common critiques of their use has been that they may increase the error in the model (Collins, 1996; King et al., 2006). The LCS specification seeks to address this concern by using structural equations to define “error-free” latent variables for each observed variable and then creating a latent variable representing the change between adjacent time points (Figure 2). This specification essentially divides the change process into multiple segments, enabling each segment to be predicted by constant growth factors (e.g., growth trajectories used in LGC specifications; Figure 2b), previous assessments (proportional change; Figure 2c), other change processes (e.g., treatment-related change; Figure 2d), or other time-invariant or time-variant predictors. Having a segmented change process also allows for the relationships among change processes to shift across time. This is accomplished by allowing change parameters, which are traditionally constrained to be equal, to vary across time. The most common LCS specification includes proportional change and constant change processes, holds the error terms of the observed variables to be equal, and constrains the intercepts and residual variances of the LCSs to be 0. These constraints, however, can be relaxed and more complex change processes can be added as the number of assessments and sample size increase (Grimm, An, McArdle, Zonderman, & Resnick, 2012).

Figure 2.

Graphical notation of LCS specification. SLP = Slope; Int = Intercept; LCS = Latent Change Score; α = proportional change parameters; σ2 = variance or error variance; σis = covariance; * intercept and error variance estimated for the first LCS to capture pre-post change due to the weight-control intervention.

Similar to the ALT model, the LCS model also estimates the relationships among change in OW and FNE and models developmental trajectories for each variable. Compared with the ALT specification, the LCS specification does not explicitly test the autoregressive parameters and the first assessment is included as part of the model. This provides more degrees of freedom to test other aspects of the change process, such as the intervention effect between the first and second assessments of our data.

For the purposes of our research question, both the ALT and LCS specifications allow us to model the interplay between FNE and OW while also being able to model developmental trajectories and account for stability of each process over time. Under certain conditions, the two specifications are equivalent (Bollen & Curran, 2004), but generally they are distinct and emphasize different elements of the hypothesized model of change. By incorporating autoregressive parameters, the ALT model provides an explicit test of the stability of FNE and OW overtime. By treating the initial time points as determined, the ALT model makes fewer assumptions about the change process. This means the ALT model will more closely follow the observed data, but it also means the model has fewer degrees of freedom to test for additional change processes, making it difficult to estimate change associated with the weight-control intervention in our study. Alternatively, the LCS specification models the initial time point and thus makes more assumptions about the change process being modeled, but in so doing provides additional degrees of freedom to model additional sources of variability. Because our data were collected as part of a clinical trial and we would like to model and report the change associated with participation, we selected the LCS specification to examine the reciprocal relationship between FNE and OW, while also addressing the initial change in both variables due to involvement in an intervention trial.

Sample Size

There are a number of factors that determine how many participants and how many assessments are required to appropriately fit an SEM specification to longitudinal data. Like most statistical models, the quality of the data helps determine sample size, with higher amounts of measurement error requiring larger samples. For longitudinal data, it is also important to consider the number of repeated measures and overall duration of the study (Collins, 2006). Precision increases as the number of assessments increases and as the duration of the study increases. Most longitudinal statistical models require at least three assessments, but the appropriate number depends on the nature of the phenomenon being studied—complex change trajectories require more frequent assessment (Curran, Obeidat, & Losardo, 2010). The duration of a study is also dependent on the nature of the phenomenon—more time is required for phenomena that change over a longer period than those that change over a shorter period.

Given the number of factors that contribute to determining an appropriate sample size, it is difficult to give a general recommendation about how many participants or time points are needed to use structural equation specifications for longitudinal data. Some have recommended that 100–200 participants are needed to provide stable parameter estimates, but growth curve models have been successfully applied in samples significantly smaller than 100 (Curran, Obeidat, & Losardo, 2010). More work is needed in providing guidance on how these methods work in small longitudinal samples. In the absence of such guidance, as a general rule, more assumptions must be made when fitting statistical models to data limited by small samples or few assessment occasions. For example, RMANOVA, which has routinely been used in smaller samples, is a restricted SEM specification that makes a number of assumptions about the data, including homogeneity of variance and covariance across time and consistency of change trajectories across individuals. As sample size increases, assumptions can be relaxed, and it is easier to address issues with ill-conditioned data (i.e., data that do not meet the assumptions of multivariate normality).

The number of considerations influencing sample size also makes it difficult to estimate how many participants are required to achieve adequate power for a given analysis. There are some off-the-shelf power calculators that can handle structural equation and growth models (e.g., Optimal Design: Raudenbush et al., 2011; PinT: Snijders & Bosker, 1993). If more flexibility is required, power can be estimated using Monte Carlo simulation (Muthén & Muthén, 2002). This approach can be time consuming and often requires pilot data to build the population model from which the simulations are drawn, but it can be used to provide a power estimate for the exact model researchers expect to run.

Assumptions

Before moving on to fitting the LCS specification to our data, it is important to discuss the assumptions being made by the LCS model. Due to advances in statistical theory and analytic software, it is possible to relax many traditional assumptions such as independent observations, multivariate normality, independent error terms, and homogeneity of variance (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). However, models that relax these assumptions typically require larger sample sizes and more assessments, as well as specialty software such as Mplus. In practice, the LCS change specification makes many of the same assumptions used by traditional statistical approaches, including independent observations, normally distributed error terms with means of 0, and multivariate normality.

There are additional assumptions to consider for models focused on change. First, the models generally assume that the measurement of observed variables is invariant across time, meaning the psychometric properties of the instruments used to measure the outcomes do not change with repeated measurements. Similar to previous assumptions, this assumption can be tested and possibly relaxed with the inclusion of more information, such as including a measurement model with multiple indicators (Millsap, 2007). Second, change models generally assume that the relationships among change processes are invariant across individuals. Certain aspects of the change process, such as intercept or slope, can be allowed to vary across individuals by including a latent variable, but, generally, the change processes (e.g., auto-regressive, proportional change, cross-lagged) are assumed to be the same across individuals.

For LCS models, it is common to assume independent error terms with equal variance across assessments, constrain the intercepts and error terms for the LCSs to be 0, and constrain the proportional change and cross-lagged parameters to be equal across assessments. These assumptions can be relaxed with appropriate theoretical justification and sufficient information (e.g., sample size, number of assessments). However, before relaxing these assumptions, it is important to consider the implications behind assumptions being made in each model. For example, independent error terms suggest that all possible links between two adjacent observed variables are included in the model. Relaxing this assumption and allowing errors to correlate suggests that there are unmeasured processes that are influencing the observed variables. For our data, these may include processes such as a media campaign focused on weight control, changes in other public weight-control service, or other time-varying confounds. If this assumption is reasonable and there are a sufficient number of assessments to identify the model, then correlated errors can be added to the model. Another example is relaxing the constraints on the intercept and error terms of the LCSs. The intercept and residual variance is often constrained to 0, suggesting that all of the change between assessments is accounted for by the modeled change processes (i.e., proportional change, constant change); releasing this null constraint would suggest that there are additional change processes beyond the proportional and constant change processes that are contributing to change in the observed variables. For example, our data had an intervention that took place between the first and second assessment, which is modeled by releasing the null constraint on the error term of the first LCS.

Finally, when modeling change processes, it is important to consider the timing of assessments. As part of the definition of the LCSs, the LCS specification constrains the autoregressive parameters to a value of “1,” which suggests that the lag between assessments is equal. In other words, the LCS specification assumes equal spacing between assessment points. This assumption does not preclude analysis of data collected at unequally spaced intervals, but it does require the researcher to incorporate the time structure of the data into the analysis. One convenient way to accomplish this task is to create noninformative latent variables (i.e., all aspects of the latent variable are defined by the specification and no parameters are independently estimated for the latent variable) as placeholders for the absent assessment points. The use of such placeholders is graphically depicted in Figures 1 and 2, and the Mplus syntax for their implementation is included in the Appendix (see Supplementary Material Online).

Estimating the LCS Model With the Behavioral Weight-Control Intervention Data

When fitting a complex change specification to observed data, it is helpful to begin with a simple specification and work toward more complex specifications. The graphical notations for increasingly complex LCS specifications are presented in Figure 2. For our data, evaluations of the global fit between the models and the observed data were evaluated using sample size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation, Comparative Fit Index, and the chi-square test of model fit (Table I). All models were estimated using Mplus 6.12 with a maximum likelihood estimator that provides robust standard errors (Muthén & Muthén, 1998). Missing data were accounted for using full information maximum likelihood. Please refer to an article by Little, Jorgensen, Lang, and Moore (in press) for a nice summary of missing data issues in longitudinal data. We first fit univariate models for FNE and OW. For both processes, we began by fitting a RMANOVA with linear basis (Figure 2a) and then fit an LGC model (Figure 2b). Because these models are inconsistent with our theory of change, we did not expect these models to provide a good fit to the observed data. They do, however, provide a point of comparison for deciding if proceeding to the more complex specifications is warranted. Please note that the RMANOVA and LGC specifications are depicted using the notation of LCS. Although this notation looks different from traditional graphical representation of LGC models, they represent equivalent specifications. We next fit a proportional change model (Figure 2c) where the LCSs were predicted by the error-free latent variable from the previous assessment. The final univariate model that we fit was the dual-change LCS model that integrated the proportional change model with the LGC model (Figure 2d).

Table I.

Chi-Squared Test of Fit and Fit Statistics for Autoregressive, LGC, ALT, and LCS Models

| χ2 | df | p | BIC | CFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overweight | ||||||

| A) Repeated-measures ANOVA | 115.90 | 10 | <.01 | 3,201.30 | .56 | .30 |

| B) LGC | 94.35 | 8 | <.01 | 3,185.69 | .64 | .30 |

| C) LCS–Proportional change | 113.50 | 9 | <.01 | 3,198.82 | .57 | .31 |

| D) LCS–Dual change | 57.74 | 7 | <.01 | 3,132.00 | .79 | .25 |

| E) LCS–Dual change + Tx effect | 20.47 | 5 | <.01 | 3,092.84 | .94 | .16 |

| F) LCS–Dual change + Tx effect + modificationsa | 5.72 | 4 | .22 | 3,077.43 | .99 | .06 |

| Fear of Negative Evaluation | ||||||

| A) Repeated-measures ANOVA | 24.45 | 10 | <.01 | 2,413.96 | .67 | .11 |

| B) LGC | 14.22 | 8 | .08 | 2,405.91 | .86 | .08 |

| C) LCS–Proportional change | 24.56 | 9 | .09 | 2,414.59 | .63 | .12 |

| D) LCS–Dual change | 7.64 | 7 | .37 | 2,396.59 | .98 | .03 |

| E) LCS–Dual change + Tx effect | 6.89 | 6 | .33 | 2,364.58 | .98 | .04 |

| Multivariate LCS | 42.65 | 21 | <.01 | 5,477.16 | .95 | .09 |

| Multivariate LCS + modificationsa | 28.16 | 20 | .11 | 5,464.92 | .98 | .06 |

Note. BIC = Sample size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; LCS = Latent Change Score Model; LGC = Latent Growth Curve; ALT = Autoregressive Latent Trajectory; Tx = Treatment.

aThe model was modified post hoc by estimating the residual variance of the latent different scores between the 12- and 24-month assessments.

To account for the intervention-related improvement between the baseline and 4-month assessment, we removed the null constraint on the intercept and error term of the first LCS (Figure 2d). Estimating the intercept term captures the average change across the sample following the intervention, above and beyond what is explained by the constant change and proportional change processes. Estimating the error term allows for estimation of individual variability in how participants responded to the intervention.

Although there are no concrete thresholds for sample size, smaller samples increase the likelihood that there will be problems estimating the model. For our models, there were no issues estimating the model for OW, but the FNE model had numeric difficulties (i.e., the covariance matrix for the latent variables was nonpositive definite). Specifically, the error variance for the first LCS was negative, which can occur when sample sizes are relatively small and the variance being estimated is close to 0. The difficulties were remedied by making additional assumptions that simplified the model: we constrained the error variance for the first LCS to 0, eliminating individual variability in response to the intervention for FNE. Fixing a nonsignificant negative variance to 0 is one way to address this issue (Dillon, Kumar, & Mulani, 1987); an alternative strategy would be to use a Bayesian estimator (Muthén & Muthén, 1998).

Model Selection

Evaluating the global fit of the statistical model to the observed data helps select parsimonious models that show reasonable fit to the data. It is important to note, however, that there has been a robust debate regarding how best to evaluate global fit (Barrett, 2007; Bentler, 2007), and that it is only one of a number of issues to consider when evaluating the appropriateness of a statistical model. Other considerations include how well the model estimates key parameters of interest (e.g., treatment effect, cross-lagged effect), the consistency between current theory and the statistical model, and how well the model predicts clinically relevant outcomes (Barrett, 2007; Collins, 2006; Tomarken & Waller, 2005). Moreover, there is evidence that the model with the best global fit is not always the most appropriate model (Tomarken & Waller, 2005; Voelkle, 2008). Thus, pursuing global fit without addressing these other considerations risks creating a model that closely fits the sample data, but does not generalize to other samples or populations.

The fit statistics for each of the increasingly complex models are presented in Table I. According to the chi-square test of fit and the other indices of model fit, the more complex models fit better than the more basic models (i.e., RMANOVA, LGC). The model fit indices suggested that the final model for OW was a poor fit to the observed data, and that the statistical model of change may need refinement. An exploratory analysis using the modification indices produced as part of the Mplus output suggested that the model fit would improve by releasing the null constraint on the error terms for the change scores between the 12- and 24-month assessments. Releasing this constraint suggests that there is another change process not accounted for in our statistical model that is influencing change in percent overweight between the 12- and 24-month assessments. We proceeded to fit both the original theorized model and a model that estimated the residual variance in the change scores between the 12- and 24-month assessments—there were no substantive differences in the parameters of interest to our investigation (i.e., cross-lagged parameters between change in FNE and change in OW). Estimates from the original model are presented in the Results section.

Although we chose to test our hypotheses using an LCS, it is important to note that there are other complex LGC models we might have used. For example, using a piecewise, higher-order growth, or a growth mixture model may have improved the fit of our model (Berlin, Parra, & Williams, in press). These models emphasize different and potentially important aspects of the data, such as the shape of the developmental trajectory or modeling different change processes for different subsets of the sample, but do not align with our intent to investigate the cross-lagged relationships between OW and FNE in the context of developmental growth and treatment-related change.

Results

The results from the multivariate model (Figure 1d) are listed in Table II and identified in text by the parameter labels used in the table. Descriptive statistics are included in the MPlus output in the Appendix (see Supplementary Material Online). Because results are from a model that included multiple change processes (i.e., developmental change, proportional change, change due to the intervention, and cross-lagged relationships), coefficients are interpreted as the influence of a particular type of change process after controlling for the other change processes. The model provides estimates of the average initial values for the sample (fixed effects: FNEintercept and OWintercept) and tests whether there is variability among participants in their initial score (random effects: FNEintercept and OWintercept). For our example, on average, participants started with a score of 19.29 (p < .01) for FNE and 161.39 (p < .01) for percent overweight, with significant variability among participants in the initial score for both FNE (b = 24.47, p < .01) and OW (b = 253.25, p < .01).

Table II.

Model Parameters for the Multivariate LCS Model

| Fixed effect (StdErr) | p-Value | Random effect (StdErr) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent overweight | ||||

| OW1 | 0 | 30.92 (7.29) | <.01 | |

| OW4 | 0 | 30.92 (7.29) | <.01 | |

| OW12 | 0 | 30.92 (7.29) | <.01 | |

| OW24 | 0 | 30.92 (7.29) | <.01 | |

| OWIntercept | 161.39 (1.53) | <.01 | 253.25 (28.14) | <.01 |

| OWSlope | −0.64 (14.07) | .96 | 3.74 (1.01) | <.01 |

| Proportional change (OWn on OWn-1; αx) | 0.006 (0.09) | .95 | ||

| LCS4,1 | −9.99 (1.17) | <.01 | 29.23 (17.81) | .10 |

| LCS(8,4;12,8;16,12;20,16;24,20) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Fear of Negative Evaluation | ||||

| FNE1 | 0 | 17.38 (2.30) | <.01 | |

| FNE4 | 0 | 17.38 (2.30) | <.01 | |

| FNE12 | 0 | 17.38 (2.30) | <.01 | |

| FNE24 | 0 | 17.38 (2.30) | <.01 | |

| FNEIntercept | 19.29 (0.63) | <.01 | 24.47 (5.29) | <.01 |

| FNESlope | 4.29 (4.07) | .29 | 2.45 (2.51) | .33 |

| Proportional change (FNEn on FNEn-1; αy) | −0.25 (0.26) | .33 | ||

| LCS 4,1 | −1.45 (1.09) | .18 | 0 | |

| LCS (8,4;12,8;16,12;20,16;24,20) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Cross-lags | ||||

| FNE on OW (βy) | 0.18 (0.06) | <.01 | ||

| OW on FNE (βx) | 0.52 (0.34) | .12 | ||

| Covariances between exogenous variables | ||||

| OWIntercept with OWSlope | −7.79 (24.32) | .75 | ||

| OWIntercept with FNEIntercept | −13.18 (10.20) | .20 | ||

| OWIntercept with FNESlope | 1.57 (3.29) | .63 | ||

| OWSlope with FNEIntercept | 0.51 (2.12) | .81 | ||

| OWSlope with FNESlope | 0.39 (0.78) | .62 | ||

| FNEIntercept with FNESlope | 2.38 (4.83) | .62 |

Note. OW = Overweight status; FNE = Fear of Negative Evaluation; LCS = Latent Change Score; StdErr = Standard Error.

Greek letters correspond to Figure 1d. Fixed effects are interpreted as regression parameters (i.e., change in y given a unit change in x). Random effects are interpreted as variances. The error variances for the observed scores (OW1/FNE1 to OW24/FNE24) were constrained to be equal.

The model also provides the average trajectory overtime (fixed effects: FNEslope and OWslope) and variability in those trajectories (random effect: OWslope and FNEslope). For our data, the average developmental trajectory for FNE was 4.29 (p = .29) and OW was −0.64 (p < .01). If both these parameters were significant, they would suggest that, holding all other processes constant, FNE will increase 4.29 points and OW will decrease 0.64 points every 3 months. There was significant variability among participants around the average developmental trajectories for OW (b = 3.74, p < .01), but not for FNE (b = 2.45, p = .33).

Proportional change was not significant for either FNE or OW, but if it were, the parameters would be interpreted as follows: for FNE, the amount of change in FNE between assessment points decreases by .25 for every unit increase in the FNE score from the previous assessment; for OW, the amount of change in OW between assessment points increases by .006 for every unit increase in overweight percentage from the previous assessment.

We included treatment-related change in our model (fixed effects: FNE: LCS4,1 and OW: LCS4,1), which was not significant for FNE (b = −1.45, p = .18), but was significant for OW (b = −9.99, p < .01). The significant finding for OW suggests that after accounting for developmental and proportional change, participants’ OW decreased, on average, by 9.99 percentage points from the first to second assessment. We also evaluated whether treatment-related change varied across participants for OW (random effect: OW: LCS4,1). The finding was not significant (b = 29.23, p = .10). As mentioned previously, variability in individual treatment responses for FNE was constrained to 0 and thus not estimated by the model.

Finally, the goal of this analysis was to test whether change in FNE and change in percent overweight were reciprocally associated across time. We evaluated this question by estimating the cross-lagged relationships between change in FNE and change in OW (fixed effects: FNE on OW; fixed effects: OW on FNE). The relationship between change in OW and subsequent change in FNE was significant (b = .18, p < .01), but not the relationship between change in FNE and subsequent change in OW (b = .52, p = .12). Changes in FNE were predicted by changes in OW at the previous assessment, such that a 1 percent decrease in OW translated into a 0.18 decrease in FNE at the subsequent time point. Changes in OW were not longitudinally predicted by changes in FNE at the previous assessment (i.e., cross-lagged association). These results suggest that changes in FNE were related to earlier changes in OW, but that change in OW was not preceded by change in FNE. These findings were significant after accounting for a number of change processes that theoretically influence change in FNE and OW, including developmental change, change based on their previous assessment point (proportional change), and change related to participation in a clinical trial.

Discussion

Structural equations provide great flexibility in modeling change and can provide a better match between statistical models and theoretical formulations about change. Moreover, these complex models can be specified using any software that can run structural equations. The increased flexibility, however, greatly increases the number of decision points in an analysis, making them difficult to navigate. Technical details of complex change models (Ferrer, Hamagami, & McArdle, 2004; McArdle, 2005, 2009) and final worked examples (Hawley, Ho, Zuroff, & Blatt, 2007; King et al., 2006; Kouros & Cummings, 2010; Simons-Morton & Chen, 2006) are available in the literature; our intent has been to provide an overview of how to translate a theoretical model of how processes change overtime into a statistical model of change using a “real-world” example. We hope that this article helps provide a general overview and starting point from which to understand complex change models, and in conclusion, we would like to provide a few practical recommendations for those interested in implementing these models.

First, it is important to have a clear theoretical model of change before implementing an advanced SEM specification. Having a clear and well-articulated model of change will help reduce the number of models that need to be considered and can help guide which assumptions should be allowed or disallowed in the statistical model. Clear theories also help with communicating and justifying the model assumptions. Ideally, this hypothesized model should be articulated before the study is designed so that it can inform the number and timing of assessments (Collins, 2006).

Second, it is helpful to start with a simple specification like RMANOVA or LGC and build increasing complexity. Such a process will help identify parsimonious models and provides a point of comparison for more complex models. Not every model that is theoretically indicated will have perfect global fit, and in such situations, it is important to justify the use of such models by articulating the theoretical justifications for the statistical models and by showing that they fit better than more traditional and less complex specifications. For example, the LCS specification for overweight status did not show good global fit. However, the specification aligns nicely with our hypothesized model of change and enables individual responses to the intervention to be modeled as a latent variable. We believe these benefits outweigh the less-than-stellar global fit, especially given that the LCS model shows better fit than traditional RMANOVA or LGC specifications. Fit was improved by including a straightforward post hoc adjustment that did not influence the key findings of the analyses. It is not clear, however, if the adjustment is indicative of an important unmeasured influence on change in overweight status between the 12- and 24-month assessments or a spurious finding unique to this data set. We, therefore, presented findings from the a priori specification, despite the lack of perfect fit. To be clear, we are not recommending that global fit be disregarded, but models with less-than-perfect global fit may be considered with compelling rationale based on a clearly articulated theory of change.

Third, fitting complex versus simple models requires more information (e.g., sample size, number of assessment occasions). Identifying how much information is sufficient is difficult to determine and depends on the research question and the specific model being fit to the data. There currently is not a clear threshold for sample size for these models, and complex change specifications can be cautiously used in data with limited sample size or limited number of assessments. There are challenges to applying these specifications to limited data, such as the nonpositive definite covariance matrices that we encountered as we fit the LCS specifications to the FNE data. Fitting complex models in limited data requires an increased number of assumptions, such as constraining parameters to be equal across time, or across participants. Larger sample sizes and a greater number of assessments allow for fewer assumptions, and fewer assumptions typically result in better-fitting models. Although placing more weight on the hypothesized model of change enables the application of complex change models in limited data sets, the conclusions based on such applications should be tempered by the knowledge that the accuracy of the conclusions depends on the accuracy of the hypothesized model and accompanying assumptions. If the model is misspecified (i.e., the assumptions are incorrect), then the parameters derived from the model will be biased and the conclusions based on the model may be incorrect. It is, thus, incumbent on the researcher to make a compelling case justifying the theoretical model.

Because these complex change specifications can be fit using structural equations, they can also take advantage of the analytic techniques developed for structural equations, such as multiple group analyses, robust estimation techniques, and measurement models. With so many options, the challenge is in selecting which approaches will provide the most parsimonious answer to the research question and the closest match to the hypothesized model of change.

In sum, modern statistical approaches have provided researchers with a flexible and powerful array of tools to examine change. The promise of these models is limited by the added time and complexity required to select and fit the models. Providing clearly articulated models of change will help guide model selection and better enable researchers to begin to elucidate the complex dynamics of change within pediatric populations.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data can be found at: http://www.jpepsy.oxfordjournals.org/

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ken Bollen and Jack McArdle for their useful comments during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding

Data were provided by a study supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK; R01-DK062916) awarded to Dr. Jelalian. Dr. Rancourt’s fellowship is supported by a training grant through the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; T32-MH019927).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Barrett P. Structural equation modeling: Adjudging model fit. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:815–824. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P M. On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:825–829. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin K S, Parra G R, Williams N A. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 2): Longitudinal latent class growth and growth mixture models. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst085. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K A, Curran P J. Autoregressive latent trajectory (ALT) models: A synthesis of two traditions. Sociological Methods & Research. 2004;32:336–383. [Google Scholar]

- Collins L M. Is reliability obsolete? A commentary on “Are Simple Gain Scores Obsolete?”. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1996;20:289–292. [Google Scholar]

- Collins L M. Analysis of longitudinal data: The integration of theoretical model, temporal design, and statistical model. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:505–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach L J, Furby L. How we should measure “change”: Or should we? Psychological Bulletin. 1970;74:68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Curran P J, Obeidat K, Losardo D. Twelve frequently asked questions about growth curve modeling. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2010;11:121–136. doi: 10.1080/15248371003699969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon W R, Kumar A, Mulani N. Offending estimates in covariance structure analysis: Comments on the causes of and solutions to Heywood cases. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer E, Hamagami F, McArdle J J. Modeling latent growth curves with incomplete data using different types of structural equation modeling and multilevel software. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2004;11:452–483. [Google Scholar]

- Flora D B. Specifying piecewise latent trajectory models for longitudinal data. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2008;15:513–533. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm K J, An Y, McArdle J J, Zonderman A B, Resnick S M. Recent changes leading to subsequent changes: Extensions of multivariate latent difference score models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2012;19:268–292. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2012.659627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley L L, Ho M, Zuroff D C, Blatt S J. Stress reactivity following brief treatment for depression: Differential effects of psychotherapy and medication. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:244–256. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelalian E, Lloyd-Richardson E E, Mehlenbeck R S, Hart C N, Flynn-O’Brien K, Kaplan J, Neill M, Wing R R. Behavioral weight control treatment with supervised exercise or peer-enhanced adventure for overweight adolescents. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;157:923–928. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D A, Zautra A. Trait–state models for longitudinal data. In: Collins L M, Sayer A G, editors. New methods for the analysis of change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 243–263. [Google Scholar]

- King L A, King D W, McArdle J J, Saxe G N, Doron-LaMarca S, Orazem R J. Latent difference score approach to longitudinal trauma research. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19:771–785. doi: 10.1002/jts.20188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouros C D, Cummings E M. Longitudinal associations between husbands’ and wives’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:135–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca A M, Lopez N. Social anxiety among adolescents: Linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:83–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1022684520514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little T D, Jorgensen T D, Lang K M, Moore W. On the joys of missing data. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst048. (In press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little T D, Preacher K J, Selig J P, Card N A. New developments in latent variable panel analyses of longitudinal data. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31:357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Richardson E E, Jelalian E, Sato A F, Hart C N, Mehlenbeck R, Wing R R. Two-year follow-up of an adolescent behavioral weight control intervention. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e281–e288. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle J J. Five steps in latent curve modeling with longitudinal life-span data. Advances in Life Course Research. 2005;10:315–357. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle J J. Latent variable modeling of differences and changes with longitudinal data. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:577–605. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millsap R E. Invariance in measurement and prediction revisited. Psychometrika. 2007;72:461–473. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L K, Muthén B O. Mplus User’s Guide. 5th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L K, Muthén B O. How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;4:599–620. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Spybrook J, Congdon R, Liu X, Martinez A, Bloom H, Hill C. Optimal design software for multi-level and longitudinal research. 2011. (Version 3.01) [Software]. Retrieved from www.wtgrantfoundation.org. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney B L, Mathiason M A, Schauberger C W. Predictors of obesity in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood in a birth cohort. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011;15:1166–1175. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0689-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B G, Chen R. Over time relationships between early adolescent and peer substance use. Addictive Behavior. 2006;31:1211–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders T A B, Bosker R J. Standard errors and sample sizes for two-level research. Journal of Educational Statistics. 1993;18:237–259. [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken A J, Waller N G. Structural equation modeling: Strengths, limitations, and misconceptions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:31–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelkle M C. Reconsidering the use of Autoregressive Latent Trajectory (ALT) models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2008;43:564–591. doi: 10.1080/00273170802490665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenberg P M, Gullone E, Bokhorst C L, Heyne D A, King N J. Social evaluation fear in childhood and adolescence: Normative developmental course and continuity of individual differences. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2007;25:471–483. [Google Scholar]

- Williams R H, Zimmerman D W. Are simple gain scores obsolete? Applied Psychological Measurement. 1996;20:59. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.