Abstract

Polycystic liver disease (PLD) is a member of the cholangiopathies, a group of liver diseases in which cholangiocytes, the epithelia lining of the biliary tree, are the target cells. PLDs are caused by mutations in genes involved in intracellular signaling pathways, cell cycle regulation, and ciliogenesis, among others. We previously showed that cystic cholangiocytes have abnormal cell cycle profiles and malfunctioning cilia. Because histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) plays an important role in both cell cycle regulation and ciliary disassembly, we examined the role of HDAC6 in hepatic cystogenesis. HDAC6 protein was increased sixfold in cystic liver tissue and in cultured cholangiocytes isolated from both PCK rats (an animal model of PLD) and humans with PLD. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 by Tubastatin-A, Tubacin, and ACY-1215 decreased proliferation of cystic cholangiocytes in a dose- and time-dependent manner, and inhibited cyst growth in three-dimensional cultures. Importantly, ACY-1215 administered to PCK rats diminished liver cyst development and fibrosis. In summary, we show that HDAC6 is overexpressed in cystic cholangiocytes both in vitro and in vivo, and its pharmacological inhibition reduces cholangiocyte proliferation and cyst growth. These data suggest that HDAC6 may represent a potential novel therapeutic target for cases of PLD.

The polycystic liver diseases (PLDs) are genetic disorders that can be included in the cholangiopathies, a group of diseases of diverse etiologies, all of which have the cholangiocyte as the target cell. PLDs occur either alone or together with polycystic kidney disease (PKD).1

Mutations in the PRKCSH (protein kinase C substrate 80K-H) and Sec63 genes lead to autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease without kidney involvement by affecting the cell's post-translational protein modification machinery and ciliary signal transduction via polycystin-2 degradation.2–5 Mutations in the Pkd1 and Pkd2 genes, which encode the ciliary-associated proteins, polycystin-1 and polycystin-2, are causative for cystic degeneration of the liver and kidneys in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), whereas a mutated form of fibrocystin, encoded by the Pkhd1 gene, is found in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD).6–9

Formation and growth of hepatic cysts lined by cholangiocytes is the key feature of PLD, a process in which several intracellular signals, including calcium, and cAMP signaling are involved.10–13 Cystic cholangiocytes also have malformed cilia and overexpression, and mislocalization of solute and water transporters involved in cholangiocyte bile secretion.14,15 These molecular alterations increase the rate of cholangiocyte proliferation and secretion leading to cyst growth.15,16

Recent studies have shown a positive effect of the pan-histone deacetylase (HDAC)-inhibitor Trichostatin A (TSA) and the class I HDAC inhibitor, valproic acid (VPA), on cyst development in kidneys of an animal model of ADPKD.17,18 HDACs are a heterogeneous group of enzymes organized in classes I to IV, which have multiple functions, including epigenetic regulation of transcription via histone deacetylation. Among these HDACs, the mostly cytoplasmic histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) regulates Wnt-signaling by deacetylating β-catenin, enabling its cytosolic accumulation and nuclear translocation, where it activates transcription and cell-cycle progression.19 Furthermore, HDAC6 is involved in the resorption of cilia in tumor cells by deacetylation of microtubules forming the ciliary axoneme.20

Therefore, we assessed the potential role of HDAC6 in hepatic cystogenesis. We measured HDAC6 protein expression in cystic cholangiocytes of rodents and humans with PLD and evaluated the effects of the HDAC6-specifc inhibitors, Tubastatin-A, (ChemieTek, Indianapolis, IN) Tubacin, and ACY-1215 on cholangiocyte proliferation and cyst growth both in vitro and in vivo. To begin understanding the potential mechanisms underlying the effect of HDAC6 inhibitors on cystic cholangiocytes, downstream effector molecules such as acetylated α-tubulin and β-catenin were also tested after HDAC6 inhibition.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Culture

For in vitro experiments, we used cholangiocytes isolated from control rats, PCK rats (an animal model for ARPKD),21 healthy humans and ADPKD patients.22–24 Cholangiocytes were cultured in Collagen-I-coated flasks (BD BioCoat, San Jose, CA). All cell lines mentioned were incubated in NRC Media at 37°C, 5% CO2, 100% humidity. NRC Media contains Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 with the following additions: 0.01 mL/mL minimum essential media nonessential amino acids, 0.01 mL/mL lipid concentrate, 0.01 mL/mL minimum essential media vitamin solution, 2 mmol/L l-glutamine, 0.05 mg/mL soybean trypsin inhibitor, 0.01 mL/mL insulin/transferring/selenium-S, 5% fetal bovine serum, 30 g/mL bovine pituitary extract, 25 ng/mL epidermal growth factor, 393 ng/mL dexamethasone, 3.4 g/mL 3,3′,5-triiodo-L-thyronine, 4.11 g/mL forskolin, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

Western Blots

Protein isolated from at least three separate cultures of control and PCK rat cholangiocytes were used. Cells were scrapped, resuspended in PBS (with protease inhibitors, sodium orthovanadate, and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride), sonicated, and then diluted in Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and mercaptoethanol with equal amounts of sample protein. After SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blots were blocked, and then incubated with the following primary antibodies: HDAC6 (D-11, 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), acetylated-α-tubulin (1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), β-catenin[(D10A8) XP rabbit mAb (1:1000); Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA], phospho-β-catenin (Ser33/37/Thr41) (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), acetyl-β-catenin (K49) (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), c-myc (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), cyclin D1 (1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and actin (1:5000; Sigma-Aldrich). The membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C, washed and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with horseradish perodixase-conjugated (1:5000; Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) or IRdye 680 or 800 (1:15,000; LI-COR, Lincoln, NE) corresponding secondary antibody. The enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) system or Odyssey LI-COR Scanner was used for protein detection and the Gel-Pro Analyzer software version 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD) was used for densitometry analysis.

Proliferation Assays

Control and PCK rat cholangiocytes were cultured on Collagen-I-coated flasks (BD BioCoat) using NRC Media, detached with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, Invitogen Corp, Carlsbad, CA), transferred to collagen-I-coated 96-well plates (10,000 cells/well), and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2, 100% humidity. Treatment with 5, 10 and 20 μmol/L Tubastatin-A (ChemieTek), 1 to 2 μmol/L Tubacin (ChemieTek), or 2, 4, and 8 μmol/L ACY-1215 (generously provided by Acetylon Pharmaceutical, Inc., Boston, MA) suspended in NRC media was started 24 hours later. The drug vehicle, dimethyl sulfoxide, was suspended in NRC media as a control. Cell proliferation was assessed with the CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution (MTS; Promega, Madison, WI) and/or counting cells using the Cellometer Auto T4 Cell Counter (Nexcelom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA).

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy

Paraffin-embedded liver sections of control (n = 3) and PCK (n = 4) rats, healthy humans, and ADPKD and ARPKD patients were incubated with antibodies against HDAC6 (D-11, 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and acetylated-α-tubulin (mouse monoclonal 1:500; Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 4°C followed by 90 minutes at room temperature of fluorescent secondary antibody incubation. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY). Paraffin blocks from 3 normal, 3 ARPKD, and 3 ADPKD patients were obtained from the Mayo Clinic Tissue Registry Archives. All experimental procedures were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Boards (Institutional Review Board no. 08-005681).

PCR

RNA was isolated from control and PCK rat cholangiocytes with TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen). The cDNA was obtained using First Srand cDNA Synthesis (Invitrogen) reagents and HDAC6 primers (forward primer: 5′-TCAGCGCAGTCTTATGGATG-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GCGGTGGATGGAGAAATAGA-3′), which were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). β-catenin mRNA expression was analyzed using the TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Assay ID Rn00584431_g1) following the manufacturer's directions. The samples were normalized to 18S rRNA.

Three-Dimensional Culture

Freshly isolated bile ducts from the PCK rat were embedded in a rat-tail type I Collagen matrix (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and grown in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/L Tubastatin-A and 2 μmol/L Tubacin. Images of the growing cysts were taken every day within a period of 5 days and cyst size was measured with ImageJ software version 1.46r (NIH, Bethesda, MD). We compared circumferential areas for each cystic structure to day 0 to calculate percentages of growth as previously described.25–28

In Vivo Experiments

For in vivo experiments, 3-week-old PCK rats were injected daily intraperitoneally during 4 weeks with 30 mg/kg body weight ACY-1215 (kindly provided by Acetylon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) or vehicle. All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee of the Mayo Clinic. At the end of the treatment, rats were sacrificed and body, liver, and kidney weights were assessed. Because no significant differences were found between sexes, we grouped the animals for statistical analysis. Hepatorenal cystic and fibrotic areas were assessed using liver and kidney sections stained with picrosirius red. Both the cystic and fibrotic areas were measured using the MetaMorph Imaging software (Molecular Devices, Inc., Downingtown, PA), and data were expressed as a percentage of the total parenchyma, as previously described.26,28

Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses were conducted by two-tailed Student's t-tests to compare two groups. The cut-off P value for significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

HDAC6 Is Overexpressed in Cystic Cholangiocytes

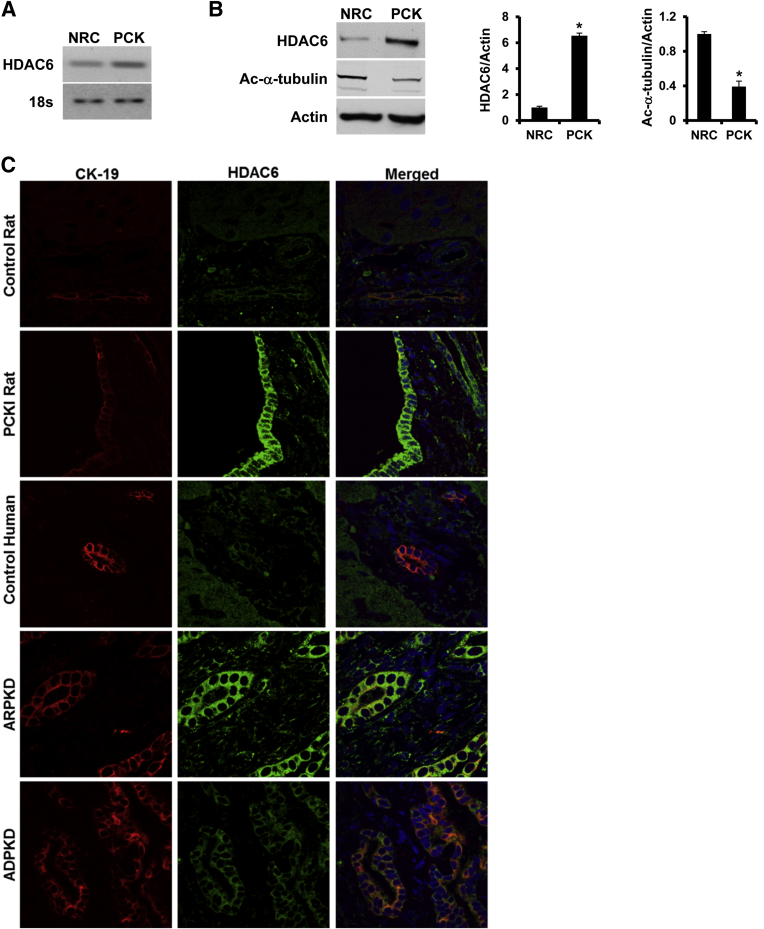

First, to assess the expression of Hdac6 mRNA in cholangiocytes, PCR using mRNA isolated from cultured rat cholangiocytes was performed. As shown in Figure 1A, Hdac6 mRNA is present in both control and PCK rat cholangiocytes. The identity of the PCR product was confirmed by sequencing. Using Western blot analysis, we found that Hdac6 protein is overexpressed 6.5-fold in PCK cholangiocytes compared to control rat cholangiocytes, and Hdac6 overexpression correlated with decreased levels of acetylated-α-tubulin, one of the main Hdac6 substrates (Figure 1B).29 The overexpression of Hdac6 observed in vitro was confirmed in vivo by confocal immunofluorescence of liver tissues. In the liver tissues of PCK rats, and ADPKD and ARPKD patients, we found that the immunoreactivity of HDAC6 was increased in hepatic cysts compared with normal rats and healthy human controls, respectively (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

HDAC6 is overexpressed in cystic cholangiocytes. A: PCR analysis showing HDAC6 mRNA expression in both normal cells (NRC) and PCK rat cholangiocytes. B: Representative of Western blots for HDAC6 and acetylated α-tubulin expression in NRC and PCK rat cholangiocytes and densitometric analysis of the Western blot analysis results (n = 3 for control; n = 4 for PCK). C: Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy of liver cysts in PCK rats (n = 5), human ADPKD (n = 3), ARPKD (n = 3) livers, and respective controls (n = 5 and 3 for rats and humans, respectively). HDAC6 is green, CK19 is red, and nuclei are blue (DAPI). ∗P < 0.05.

Inhibition of HDAC6 Decreases Cholangiocyte Proliferation and Cysts Growth in Vitro

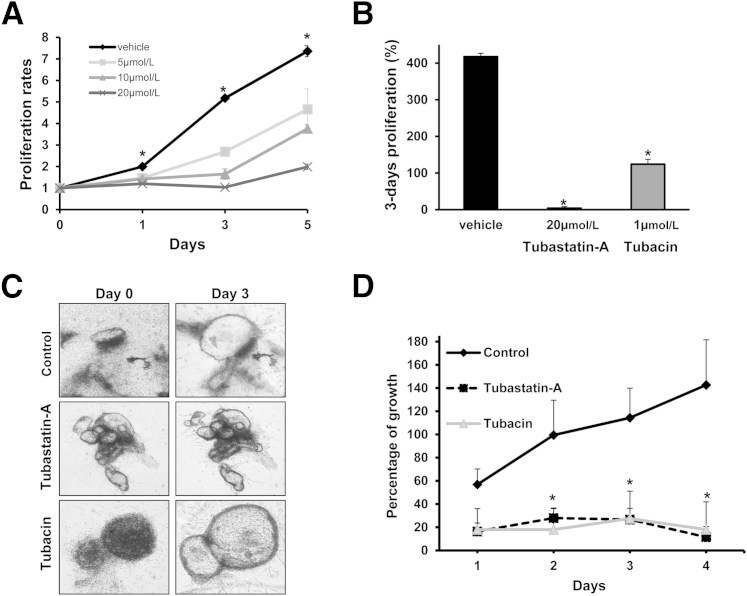

We previously showed that PCK cholangiocytes proliferate at a higher rate than control rat cholangiocytes.13 We tested our hypothesis that up-regulation of HDAC6 contributes to cholangiocyte hyperproliferation by applying the HDAC6 selective inhibitor Tubastatin-A to cultured cholangiocytes. Indeed, this drug decreased PCK cholangiocyte proliferation in a dose- and time-dependent fashion (Figure 2A). By day 3, proliferation of treated PCK cholangiocytes was reduced by 2.5-, 3.5-, and 4.15-folds for 5 μmol/L, 10 μmol/L and 20 μmol/L Tubastatin-A, respectively. Additionally, a different HDAC6 specific inhibitor, Tubacin, also reduced PCK cholangiocyte proliferation by 2.94-folds (Figure 2B). Both drugs also decreased proliferation of cultured human ADPKD cholangiocytes by 85% and 16%, respectively (Supplemental Figure S1A). To further confirm the effect of HDAC6 inhibition on proliferation, we used the Cellometer Auto T4 Cell Counter (Nexcelom Bioscience) and confirmed that the HDAC6 Inhibitor Tubastatin-A significantly reduces cystic cholangiocyte proliferation (Supplemental Figure S1B). Finally, liver cysts isolated from the PCK rat were grown in a three-dimensional collagen matrix and treated with HDAC6 inhibitors (Figure 2C). Analysis of the circumferential areas of the PCK cystic structures showed significant inhibition of cyst growth. After 4 days of drug administration, Tubastatin-A and Tubacin reduced cyst growth by 131% and 125%, respectively, compared with untreated cysts (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 decreases cystic cholangiocyte proliferation and cystic growth. Cells were incubated in 96-well plates and proliferation was analyzed by MTS assay. A: PCK rat cholangiocytes proliferation over time with different doses of Tubastatin-A. B: PCK rat cholangiocytes after 3 days of proliferation. C: Representative images of biliary cysts freshly isolated from PCK rats. The cysts were embedded in rat tail collagen matrix and treated with two different HDAC6 specific inhibitors, Tubastatin-A and Tubacin. D: Quantitative analysis of cyst growth over time (n = 12 for 10 μmol/L Tubastatin-A; n = 4 for 2 μmol/L Tubacin; n = 16 for untreated controls). Original magnification ×40 (C) (∗P < 0.05).

Inhibition of HDAC6 Correlates with a Decrease in β-Catenin Protein Level

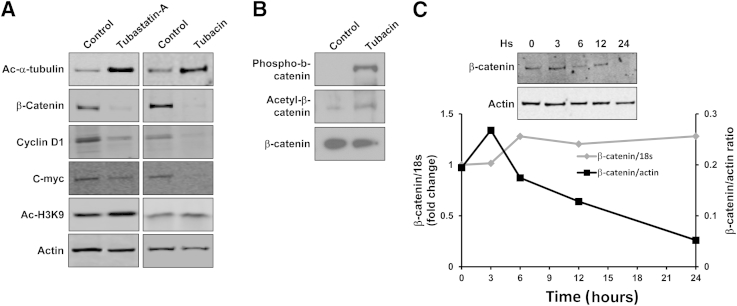

For a better understanding of the mechanisms that are responsible for the inhibition of PCK cholangiocyte proliferation and cyst growth in three-dimensional culture, we treated cultured PCK cholangiocytes with Tubastatin-A and Tubacin, and we determined the amount of acetylated α-tubulin and β-catenin by using Western blot analysis. As expected, PCK cholangiocytes treated with Tubastatin-A and Tubacin had increased levels of acetylated α-tubulin (13- and 2.3-fold) compared with untreated cells (Figure 3A). In contrast, the levels of β-catenin were decreased by 2.2-fold, and fivefold after treatment with Tubastatin-A and Tubacin, respectively (Figure 3A). Furthermore, immunofluorescence analysis of β-catenin subcellular localization also demonstrated decreased expression both in nuclei and cytoplasm induced by HDAC6 inhibition (Supplemental Figure S2). Consistent with β-catenin reduction, HDAC6 inhibition induced a decrease in the β-catenin gene target products cyclin D1 and c-myc, while the levels of acetylated histone H3 remained unaffected (Figure 3A). Furthermore, HDAC6 inhibition induced increased β-catenin acetylation at Lys49 and phosphorylation at Ser33, Ser37, and/or Thr41 (Figure 3B), consistent with β-catenin destabilization and targeting to degradation, as previously described.19,30 β-catenin protein decreases over time when cells have been treated with the HDAC6 inhibitor, whereas the levels of β-catenin mRNA remain stable, suggesting that HDAC6 inhibition induces the degradation of β-catenin protein (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

HDAC6 inhibitors increase acetylated α-tubulin and decrease β-catenin. PCK cholangiocytes treated with 20 μmol/L Tubastatin-A or 2 μmol/L Tubacin were lysed and used for Western blot analysis. A: Representative images of Western blots (n = 3). Actin was used as a loading control. B: Representative images of Western blots (n = 3). Total-β-catenin was used as a loading control. C: Western blots and RT-PCR analysis over time after treatment with 2 μmol/L Tubacin.

The Specific HADC6 Inhibitor ACY-1215 Decreases Cyst Formation in Vivo

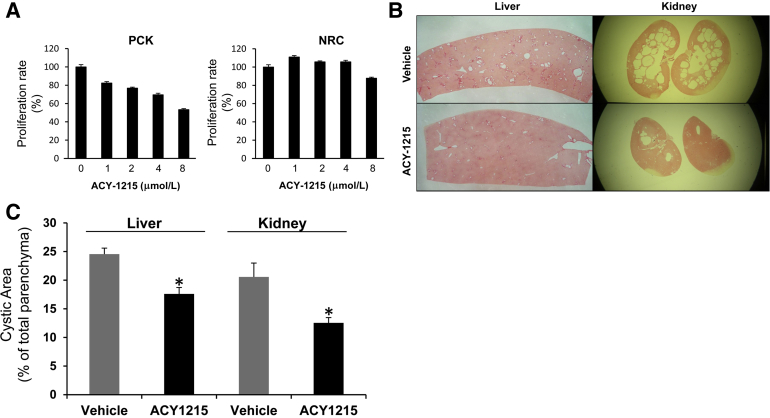

To further assess the potential role of HDAC6 inhibition as a potential therapeutic approach for PLD, we evaluated the effect of the recently developed, orally bioavailable drug, ACY-1215.31 First, we assessed the effect of ACY-1215 in the proliferation rates of normal and PCK cholangiocytes. ACY-1215 inhibited PCK cells proliferation in a dose-dependent manner and had no significant effect on proliferation of normal cells (Figure 4A). Then, we tested the effect of the drug in vivo, using the PLD animal model, the PCK rat. We found a significant reduction in both the liver and kidney cyst area [by 28.4% and 39.0%, respectively (Figure 4, B and C)]. Importantly, liver fibrosis was also reduced by 30.5% (P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

ACY-1215 inhibits cyst growth in vivo. A: Proliferation assays on normal cells (NRCs) and cystic cholangiocytes (PCKs) incubated in the presence of different doses of AYC-1215. B: Representative liver and kidney sections stained with picrosirius red from PCK rats treated with vehicle (n = 8) or ACY-1215 (n = 8). C: Quantification analysis of cystic area expressed as percentage of total parenchyma area (∗P < 0.05).

Discussion

Our key findings relate to the potential role of HDAC6 in the pathogenesis of cystic liver disease. We showed that: i) HDAC6 protein is overexpressed in cultured PCK rat and ADPKD and ARPKD cholangiocytes, ii) inhibition of HDAC6 with Tubastatin-A, Tubacin, or ACY-1215 decreased proliferation of both cultured PCK rat cholangiocytes and human ADPKD cultured cholangiocytes in a time- and dose-dependent fashion, iii) pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 reduced proliferation of cystic bile ducts isolated from the PCK rat and cultured in a three-dimensional collagen matrix, iv) HDAC6 inhibition increases the expression of acetylated-α-tubulin and decreases the expression of β-catenin, and v) pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 reduced liver and kidney cyst growth in an animal model of PLD. Taken together, our data suggest that HDAC6 plays a potential role in the development of liver cysts and its pharmacological inhibition reduces cystic growth by a mechanism that may involve inhibition of β-catenin.

HDAC6 overexpression in cholangiocytes of these benign hyperproliferative diseases, both in the PCK rat and in human ADPKD and ARPKD, is in agreement with the overexpression reported in cystic kidneys of the ADPKD mice model, pkd1 mutant.32 Furthermore, HDAC6 overexpression is consistent with the observed reduction of one of its main targets, acetylated-α-tubulin (Figure 1B). However, to our knowledge, this is the first report of HDAC6 overexpression in PLD.

The mechanisms underlying HDAC6 overexpression remain to be elucidated, but potential mechanisms may involve the CREB1 response element found in the upstream region of Hdac6 promoter, in combination with the pathological increased intracellular levels of cAMP described in polycystic diseases, which would ultimately activate PKA-CREB1 cascade and HDAC6 expression.1,13,26,33,34 Other possibilities are increased half-life of HDAC6 protein or decreased expression of specific microRNAs targeting HDAC6 mRNA, as previously described to be the case for CDC25A.27

Our findings that both human ADPKD and PCK rat cholangiocytes respond to HDAC6 inhibition by Tubastatin-A, Tubacin, and ACY-1215 with reduced proliferation, indicate HDAC6 dysregulation may be indeed important for cyst growth. Furthermore, the three-dimensional culture system, in which bile ducts isolated from the PCK rat are treated with Tubastatin-A and Tubacin, showed a significant decrease in cyst development, which encouraged our in vivo studies with the orally bioavailable, recently developed, HDAC6 inhibitor, ACY-1215, demonstrating its potential as a therapeutic approach for PLDs.

In an attempt to find potential new drugs capable of attenuating PKD, the HDAC pan-inhibitor TSA and the class I HDAC inhibitor VPA showed efficacy in the kidney phenotype of animal models of PKD; however, no information on PLD or human cystic cells were available until now.17,18 TSA and VPA are known to target multiply HDACs, which makes it difficult to determine whether the observed effect was due to the inhibition of one or more HDACs, even though one of these studies suggested HDAC1 as the main player.17 Our study is the first to test HDAC6 specific inhibitors in PLD models, implicating that HDAC6 may be an attractive molecular target in this disease.

There has been considerable progress in unraveling the complex molecular events responsible for cyst formation and growth in PLD.1,13,15,26–28,34–38 Our findings place HDAC6 among the already established molecules and pathways that are dysregulated in PLD. HDAC6 has not been previously linked to PLD; however, overexpression of HDAC6 has been reported in multiple tumors including cholangiocarcinoma. Indeed, the HDAC6 inhibitor, Tubastatin-A, is able to reduce cholangiocarcinoma growth in vitro and in vivo while restoring the expression of primary cilia in tumor cells.20 Because the PLDs can be considered a benign hyperproliferative condition,39,40 and increased cell proliferation, as well as ciliary distortion, malformation and loss are common features of polycystic diseases,1,16,26,41,42 our data suggest that HDAC6 might play a critical role in PLD pathogenesis.

Due to the involvement of HDACs in cancer, several inhibitory molecules have been developed and extensively tested. Among them, vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid) has been approved in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma,43 and TSA and VPA suppressed kidney cyst formation in animal models of PKD.17,18 Our findings are consistent with these previous studies, suggesting HDAC inhibitors could be explored as therapeutic agents for the treatment of polycystic diseases. Here, we propose to specifically target HDAC6, which would have less undesirable secondary effects, for the treatment of polycystic liver diseases. Wild-type zebrafish treated with the HDAC pan-inhibitor TSA, the class I specific inhibitor VPA, or hdac1 morpholinos, induced curve body axis, light pigmentation, abnormal pectoral fin formation, and pericardic edema. On the other hand, hdac6 morpholinos failed to produce such phenotypes.17 This suggests the use of HDAC6 specific inhibitors for PKD treatment would potentially have less deleterious secondary effects in comparison with the broader effects induced by pan-HDACs inhibitors. Furthermore, in contrast to HDAC1, -2, -3, -4, -7, and -8, HDAC6 knock-out mice are viable and fertile,44,45 supporting the concept that treatment with HDAC6-specific inhibitors will have minimal adverse effects. In fact, our in vivo experiment demonstrated no obvious toxic effect in treated animals and suggests that the pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 by ACY-1215 could be a potential novel therapeutic approach for PLDs.

HDAC6 has at least five known targets (ie, α-tubulin, β-catenin, cortactin, heat-shock-protein 90, and the redox regulatory proteins PrxI and PrxII).19,20,30 Herein, we assessed two targets that may be related to cystogenesis: acetylated-α-tubulin (major ciliary component) and β-catenin. The abnormal activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, resulting in nuclear accumulation of β-catenin, is characteristic in polycystic kidney disease.46–49 It has been reported that β-catenin nuclear localization is regulated by HDAC6-dependent deacetylation in the colon cancer cell line HCT116. β-catenin deacetylation inhibits its degradation leading to accumulation in the cytosol and nuclear translocation, where it activates pro-proliferative genes such as c-myc and cyclinD1.19 Our data showing a decreased expression of β-catenin induced by HDAC6 inhibitors suggest β-catenin may be involved in PLD pathogenesis, consistent with the recent study by Spirli et al49 using fibrocystin-defective cholangiocytes. Furthermore, our data show that HDAC6 inhibition reduces the β-catenin target gene products, c-myc and cyclin D1. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that our data suggesting that decreased cystic growth induced by HDAC6 inhibition is related to the degradation of β-catenin needs further study, in particular because, in addition to β-catenin, HDAC6 has multiple other targets, as noted above, that may also be involved in cyst growth regulation. Furthermore, β-catenin can also be phosphorylated at Ser-552 and Ser-675 by PKA.49 The phosphorylation at these sites induces the activity of β-catenin rather than degradation, and the possibility that HDAC6 inhibition may also affect these phosphorylation sites cannot be excluded.

Our study identified HDAC6 as a new molecular target in cystic cholangiocytes, which can be selectively inhibited and subsequently decreasing cell proliferation and cyst growth by affecting downstream signaling known to be involved in the cystic diseases. Our in vitro data, and our in vivo studies with the recently developed ACY-1215,31 which is now in clinical trials for multiple myeloma, suggest that the pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 may be a potential therapeutic approach for patients with PLD, including ADPKD and ARPKD.

In Summary, HDAC6 is overexpressed in cholangiocytes derived from the PCK rat, liver cysts of the PCK rat, and ADPKD and ARPKD patients. Selective inhibitors of HDAC6, Tubastatin-A, Tubacin, and ACY-1215 decrease cell proliferation in cholangiocytes derived from the PCK rat and human patient with ADPKD and reduce cyst growth in vitro and in vivo. The data are suggestive of the possibility that degradation of β-catenin may be a potential mechanism for the decreased cyst growth induced by HDAC6 inhibition, although further analysis is warranted. Taken together, our data identified HDAC6 as a new molecular target in polycystic liver disease and implicates the potential use of HDAC6 inhibitors in the treatment of PLD.

Footnotes

Supported by Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology Pilot and Feasibility Award P30DK084567 (S.A.G.), R21 R21CA166635 (S.A.G.), and R01 DK24031 (N.F.L.).

Disclosures: None declared.

Contributor Information

Sergio A. Gradilone, Email: gradilone.sergio@mayo.edu.

Nicholas F. LaRusso, Email: larusso.nicholas@mayo.edu.

Supplemental Data

A: Human ADPKD 3-day proliferation assay. B: PCK cells proliferation analysis by cell counting showing the effect of 20 μmol/L Tubastatin-A. ∗P < 0.05.

A: PCK cholangiocytes were treated with HDAC6 inhibitors; β-catenin expression was analyzed by immunofluorescence and compared with normal cells (NRCs). Top panels show β-catenin. Bottom panels show β-catenin in green and nuclei in blue with DAPI. B: β-catenin fluorescence quantification assessment in nucleus and cytoplasm compared with NRCs.

References

- 1.Masyuk T., Masyuk A., LaRusso N. Cholangiociliopathies: genetics, molecular mechanisms and potential therapies. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25:265–271. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328328f4ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drenth J.P., te Morsche R.H., Smink R., Bonifacino J.S., Jansen J.B. Germline mutations in PRKCSH are associated with autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2003;33:345–347. doi: 10.1038/ng1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davila S., Furu L., Gharavi A.G., Tian X., Onoe T., Qian Q., Li A., Cai Y., Kamath P.S., King B.F., Azurmendi P.J., Tahvanainen P., Kaariainen H., Hockerstedt K., Devuyst O., Pirson Y., Martin R.S., Lifton R.P., Tahvanainen E., Torres V.E., Somlo S. Mutations in SEC63 cause autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36:575–577. doi: 10.1038/ng1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woollatt E., Pine K.A., Shine J., Sutherland G.R., Iismaa T.P. Human Sec63 endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein, map position 6q21. Chromosome Res. 1999;7:77. doi: 10.1023/a:1009283530544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao H., Wang Y., Wegierski T., Skouloudaki K., Putz M., Fu X., Engel C., Boehlke C., Peng H., Kuehn E.W., Kim E., Kramer-Zucker A., Walz G. PRKCSH/80K-H, the protein mutated in polycystic liver disease, protects polycystin-2/TRPP2 against HERP-mediated degradation. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:16–24. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes J., Ward C.J., Peral B., Aspinwall R., Clark K., San Millan J.L., Gamble V., Harris P.C. The polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD1) gene encodes a novel protein with multiple cell recognition domains. Nat Genet. 1995;10:151–160. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mochizuki T., Wu G., Hayashi T., Xenophontos S.L., Veldhuisen B., Saris J.J., Reynolds D.M., Cai Y., Gabow P.A., Pierides A., Kimberling W.J., Breuning M.H., Deltas C.C., Peters D.J., Somlo S. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science. 1996;272:1339–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onuchic L.F., Furu L., Nagasawa Y., Hou X., Eggermann T., Ren Z., Bergmann C., Senderek J., Esquivel E., Zeltner R., Rudnik-Schoneborn S., Mrug M., Sweeney W., Avner E.D., Zerres K., Guay-Woodford L.M., Somlo S., Germino G.G. PKHD1, the polycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1 gene, encodes a novel large protein containing multiple immunoglobulin-like plexin-transcription-factor domains and parallel beta-helix 1 repeats. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1305–1317. doi: 10.1086/340448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward C.J., Hogan M.C., Rossetti S., Walker D., Sneddon T., Wang X., Kubly V., Cunningham J.M., Bacallao R., Ishibashi M., Milliner D.S., Torres V.E., Harris P.C. The gene mutated in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease encodes a large, receptor-like protein. Nat Genet. 2002;30:259–269. doi: 10.1038/ng833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lal M., Song X., Pluznick J.L., Di Giovanni V., Merrick D.M., Rosenblum N.D., Chauvet V., Gottardi C.J., Pei Y., Caplan M.J. Polycystin-1 C-terminal tail associates with beta-catenin and inhibits canonical Wnt signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3105–3117. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaguchi T., Hempson S.J., Reif G.A., Hedge A.M., Wallace D.P. Calcium restores a normal proliferation phenotype in human polycystic kidney disease epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:178–187. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005060645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi T., Nagao S., Wallace D.P., Belibi F.A., Cowley B.D., Pelling J.C., Grantham J.J. Cyclic AMP activates B-Raf and ERK in cyst epithelial cells from autosomal-dominant polycystic kidneys. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1983–1994. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banales J.M., Masyuk T.V., Gradilone S.A., Masyuk A.I., Medina J.F., LaRusso N.F. The cAMP effectors Epac and protein kinase a (PKA) are involved in the hepatic cystogenesis of an animal model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) Hepatology. 2009;49:160–174. doi: 10.1002/hep.22636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masyuk T.V., Huang B.Q., Ward C.J., Masyuk A.I., Yuan D., Splinter P.L., Punyashthiti R., Ritman E.L., Torres V.E., Harris P.C., LaRusso N.F. Defects in cholangiocyte fibrocystin expression and ciliary structure in the PCK rat. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banales J.M., Masyuk T.V., Bogert P.S., Huang B.Q., Gradilone S.A., Lee S.O., Stroope A.J., Masyuk A.I., Medina J.F., LaRusso N.F. Hepatic cystogenesis is associated with abnormal expression and location of ion transporters and water channels in an animal model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1637–1646. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alvaro D., Onori P., Alpini G., Franchitto A., Jefferson D.M., Torrice A., Cardinale V., Stefanelli F., Mancino M.G., Strazzabosco M., Angelico M., Attili A., Gaudio E. Morphological and functional features of hepatic cyst epithelium in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:321–332. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao Y., Semanchik N., Lee S.H., Somlo S., Barbano P.E., Coifman R., Sun Z. Chemical modifier screen identifies HDAC inhibitors as suppressors of PKD models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21819–21824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911987106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan L.X., Li X., Magenheimer B., Calvet J.P., Li X. Inhibition of histone deacetylases targets the transcription regulator Id2 to attenuate cystic epithelial cell proliferation. Kidney Int. 2012;81:76–85. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y., Zhang X., Polakiewicz R.D., Yao T.P., Comb M.J. HDAC6 is required for epidermal growth factor-induced beta-catenin nuclear localization. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12686–12690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C700185200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gradilone S.A., Radtke B.N., Bogert P.S., Huang B.Q., Gajdos G.B., Larusso N.F. HDAC6 inhibition restores ciliary expression and decreases tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2259–2270. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vroman B., LaRusso N.F. Development and characterization of polarized primary cultures of rat intrahepatic bile duct epithelial cells. Lab Invest. 1996;74:303–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masyuk A.I., Huang B.Q., Ward C.J., Gradilone S.A., Banales J.M., Masyuk T.V., Radtke B., Splinter P.L., Larusso N.F. Biliary exosomes influence cholangiocyte regulatory mechanisms and proliferation through interaction with primary cilia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G990–G999. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00093.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Hara S.P., Splinter P.L., Trussoni C.E., Gajdos G.B., Lineswala P.N., LaRusso N.F. Cholangiocyte N-Ras protein mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin 6 secretion and proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30352–30360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banales J.M., Saez E., Uriz M., Sarvide S., Urribarri A.D., Splinter P., Tietz Bogert P.S., Bujanda L., Prieto J., Medina J.F., Larusso N.F. Up-regulation of microRNA 506 leads to decreased Cl(-)/HCO(3) (-) anion exchanger 2 expression in biliary epithelium of patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2012;56:687–697. doi: 10.1002/hep.25691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muff M.A., Masyuk T.V., Stroope A.J., Huang B.Q., Splinter P.L., Lee S.O., Larusso N.F. Development and characterization of a cholangiocyte cell line from the PCK rat, an animal model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Lab Invest. 2006;86:940–950. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masyuk T.V., Masyuk A.I., Torres V.E., Harris P.C., Larusso N.F. Octreotide inhibits hepatic cystogenesis in a rodent model of polycystic liver disease by reducing cholangiocyte adenosine 3',5'-cyclic monophosphate. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1104–1116. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S.O., Masyuk T., Splinter P., Banales J.M., Masyuk A., Stroope A., Larusso N. MicroRNA15a modulates expression of the cell-cycle regulator Cdc25A and affects hepatic cystogenesis in a rat model of polycystic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3714–3724. doi: 10.1172/JCI34922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gradilone S.A., Masyuk T.V., Huang B.Q., Banales J.M., Lehmann G.L., Radtke B.N., Stroope A., Masyuk A.I., Splinter P.L., LaRusso N.F. Activation of Trpv4 reduces the hyperproliferative phenotype of cystic cholangiocytes from an animal model of ARPKD. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:304–314.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y., Gilquin B., Khochbin S., Matthias P. Two catalytic domains are required for protein deacetylation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2401–2404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mak A.B., Nixon A.M., Kittanakom S., Stewart J.M., Chen G.I., Curak J., Gingras A.C., Mazitschek R., Neel B.G., Stagljar I., Moffat J. Regulation of CD133 by HDAC6 promotes beta-catenin signaling to suppress cancer cell differentiation. Cell Rep. 2012;2:951–963. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santo L., Hideshima T., Kung A.L., Tseng J.C., Tamang D., Yang M., Jarpe M., van Duzer J.H., Mazitschek R., Ogier W.C., Cirstea D., Rodig S., Eda H., Scullen T., Canavese M., Bradner J., Anderson K.C., Jones S.S., Raje N. Preclinical activity, pharmacodynamic, and pharmacokinetic properties of a selective HDAC6 inhibitor, ACY-1215, in combination with bortezomib in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;119:2579–2589. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-387365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu W., Fan L.X., Zhou X., Sweeney W.E., Jr., Avner E.D., Li X. HDAC6 regulates epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) endocytic trafficking and degradation in renal epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsieh T.H., Tsai C.F., Hsu C.Y., Kuo P.L., Lee J.N., Chai C.Y., Wang S.C., Tsai E.M. Phthalates induce proliferation and invasiveness of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer through the AhR/HDAC6/c-Myc signaling pathway. FASEB J. 2012;26:778–787. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-191742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masyuk A.I., Masyuk T.V., LaRusso N.F. Cholangiocyte primary cilia in liver health and disease. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2007–2012. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masyuk T.V., Radtke B.N., Stroope A.J., Banales J.M., Masyuk A.I., Gradilone S.A., Gajdos G.B., Chandok N., Bakeberg J.L., Ward C.J., Ritman E.L., Kiyokawa H., LaRusso N.F. Inhibition of Cdc25A Suppresses hepato-renal cystogenesis in rodent models of polycystic kidney and liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:622–633.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masyuk T.V., Radtke B.N., Stroope A.J., Banales J.M., Gradilone S.A., Huang B., Masyuk A.I., Hogan M.C., Torres V.E., Larusso N.F. Pasireotide is more effective than octreotide in reducing hepatorenal cystogenesis in rodents with polycystic kidney and liver diseases. Hepatology. 2013;58:409–421. doi: 10.1002/hep.26140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hogan M.C., Masyuk T.V., Page L., Holmes D.R., 3rd, Li X., Bergstralh E.J., Irazabal M.V., Kim B., King B.F., Glockner J.F., Larusso N.F., Torres V.E. Somatostatin analog therapy for severe polycystic liver disease: results after 2 years. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:3532–3539. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hogan M.C., Masyuk T.V., Page L.J., Kubly V.J., Bergstralh E.J., Li X., Kim B., King B.F., Glockner J., Holmes D.R., 3rd, Rossetti S., Harris P.C., LaRusso N.F., Torres V.E. Randomized clinical trial of long-acting somatostatin for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1052–1061. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grantham J.J. Polycystic kidney disease: neoplasia in disguise. Am J Kidney Dis. 1990;15:110–116. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park J.Y., Schutzer W.E., Lindsley J.N., Bagby S.P., Oyama T.T., Anderson S., Weiss R.H. p21 is decreased in polycystic kidney disease and leads to increased epithelial cell cycle progression: roscovitine augments p21 levels. BMC Nephrol. 2007;8:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-8-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Masyuk T., LaRusso N. Polycystic liver disease: new insights into disease pathogenesis. Hepatology. 2006;43:906–908. doi: 10.1002/hep.21199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Masyuk T.V., Huang B.Q., Masyuk A.I., Ritman E.L., Torres V.E., Wang X., Harris P.C., Larusso N.F. Biliary dysgenesis in the PCK rat, an orthologous model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1719–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63427-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finnin M.S., Donigian J.R., Cohen A., Richon V.M., Rifkind R.A., Marks P.A., Breslow R., Pavletich N.P. Structures of a histone deacetylase homologue bound to the TSA and SAHA inhibitors. Nature. 1999;401:188–193. doi: 10.1038/43710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y., Kwon S., Yamaguchi T., Cubizolles F., Rousseaux S., Kneissel M., Cao C., Li N., Cheng H.L., Chua K., Lombard D., Mizeracki A., Matthias G., Alt F.W., Khochbin S., Matthias P. Mice lacking histone deacetylase 6 have hyperacetylated tubulin but are viable and develop normally. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:1688–1701. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01154-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haberland M., Montgomery R.L., Olson E.N. The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin F., Hiesberger T., Cordes K., Sinclair A.M., Goldstein L.S., Somlo S., Igarashi P. Kidney-specific inactivation of the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II inhibits renal ciliogenesis and produces polycystic kidney disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5286–5291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0836980100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lancaster M.A., Gleeson J.G. Cystic kidney disease: the role of Wnt signaling. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:349–360. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wuebken A., Schmidt-Ott K.M. WNT/beta-catenin signaling in polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;80:135–138. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spirli C., Locatelli L., Morell C.M., Fiorotto R., Morton S.D., Cadamuro M., Fabris L., Strazzabosco M. Protein kinase a-dependent pSer -beta-catenin, a novel signaling defect in a mouse model of congenital hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology. 2013;58:1713–1723. doi: 10.1002/hep.26554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A: Human ADPKD 3-day proliferation assay. B: PCK cells proliferation analysis by cell counting showing the effect of 20 μmol/L Tubastatin-A. ∗P < 0.05.

A: PCK cholangiocytes were treated with HDAC6 inhibitors; β-catenin expression was analyzed by immunofluorescence and compared with normal cells (NRCs). Top panels show β-catenin. Bottom panels show β-catenin in green and nuclei in blue with DAPI. B: β-catenin fluorescence quantification assessment in nucleus and cytoplasm compared with NRCs.