Abstract

Background

We use a life-course perspective to examine whether a parent’s adolescent antisocial behavior increases the chances of his or her child being involved in antisocial behavior and, if so, the extent to which different aspects of parenting mediate this relationship.

Aims/Hypotheses

We hypothesize that there will be significant levels of intergenerational continuity in antisocial behavior when parents have ongoing contact with the child and that stress from parenting and ineffective parenting styles will mediate this relationship.

Methods

We use longitudinal data from the Rochester Intergenerational Study to test these issues in structural equation models for fathers and for mothers.

Results

Parental antisocial behavior is significantly related to child antisocial behavior for mothers and for fathers who have frequent contact with the child, but not for fathers with infrequent contact. For mothers, the impact of adolescent antisocial behavior on the child’s antisocial behavior is primarily mediated through parenting stress and effective parenting. For high-contact fathers there are multiple mediating pathways that help explain the impact of their adolescent antisocial behavior on their child’s behavior.

Conclusions/Implications

The roots of antisocial behavior extend back to at least the parent’s adolescence and parenting interventions need to consider these long-term processes.

There is a well-known association between parental and child antisocial behavior; parents who have a history of involvement in delinquency, drug use, and other forms of antisocial behavior are more likely to have children who also engage in those behaviors. While some degree of intergenerational continuity in antisocial behavior is observed in many studies (e.g., Huesmann et al., 1984; Farrington et al., 2001), we have much less information about the mediating processes that bring about such continuity. Recent multigeneration longitudinal studies are beginning to address this issue by prospectively following parents and children to examine the pathways by which parental antisocial behavior creates risk for children. The present study uses data from one such study, the Rochester Intergenerational Study, to examine the role of parenting behaviors as potential mediators of intergenerational continuity. In particular, we address two key questions in intergenerational study:

Is a parent’s history of adolescent antisocial behavior significantly related to the child’s antisocial behavior?

If so, to what extent do parenting behaviors mediate that association?

CONCEPTUAL MODEL

There are several pathways which could account for intergenerational continuity. Perhaps the most parsimonious is a purely genetic model. From this perspective antisocial behavior would be caused by some genetic risk that is passed from parent to child. And, of course, there is substantial evidence of heritability for antisocial behavior (Jacobson et al., 2001; Simonoff, 2001). Heritability estimates average about 40%, however, (Rhee and Waldman, 2002) indicating that there are also substantial environmental influences at play. The present analysis focuses on these environmental influences, adopting a life-course orientation to account for intergenerational continuity.

Thornberry (2005) recently presented an intergenerational model of antisocial behavior that is rooted in interactional theory (Thornberry, 1987) and, more generally, the life-course perspective (Elder, 1997). It argues that parental involvement in antisocial behavior during adolescence has cascading developmental consequences for the individual that ultimately compromise the life chances of his or her children. Among those consequences are the disruption of social bonds during adolescence which increase the chances of disorderly transitions from adolescence to adulthood. In combination these factors increase the probability that the young adult will experience structural adversity, high levels of stress, and continued antisocial behavior, all of which have been shown to compromise effective parenting strategies, one of the strongest influences on childhood antisocial behavior. If correct, this model suggests that one pathway by which parental antisocial behavior leads to child antisocial behavior is via the life-course disruption generated as a consequence of involvement in adolescent antisocial behavior. The present analysis tests a part of this overall model, focusing on three key mediators: disorderly transitions, stress, and parenting behaviors.

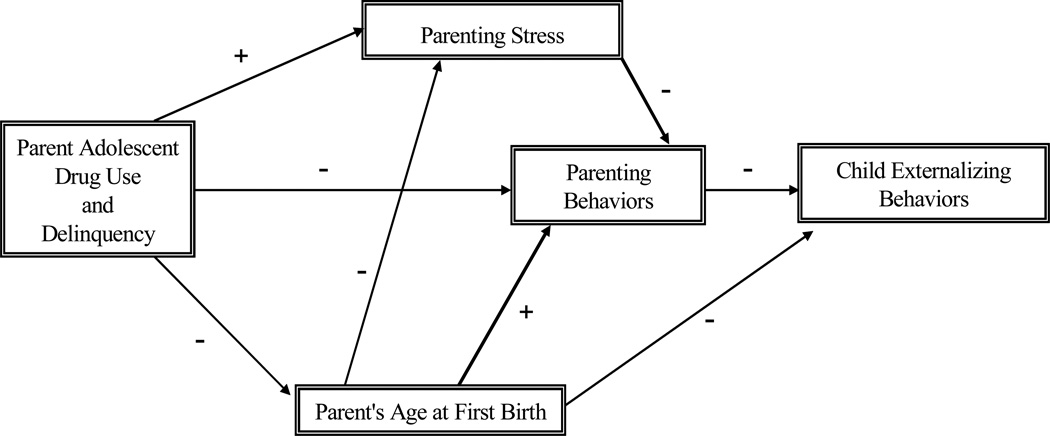

The Empirically Tested Model

The model to be empirically assessed is described in Figure 1. To assess intergenerational continuity this model examines the impact of parental adolescent drug use and delinquency on the child’s externalizing problems during childhood. The model also examines one type of precocious transition to adult roles that is likely to mediate this relationship: the parent’s age at first birth. Adolescent involvement in drug use and delinquency is predicted to decrease the age at first birth which, in turn, is expected to increase levels of stress as younger parents are developmentally less well prepared to assume the responsibility of parenthood. Here we examine stress generated by the parenting role itself. Parents who have a history of adolescent antisocial behavior and who had a child at a young age are hypothesized to experience greater degrees of stress related specifically to the role of parent. In turn, all of these earlier characteristics are expected to lead to ineffective parenting behaviors characterized by weak affective ties to the child, poor monitoring and supervision, and inconsistent, explosive disciplinary styles. These parenting behaviors have the most proximal and powerful impact on the child’s early manifestation of antisocial behavior and are expected to be an important mediator of the impact of the earlier variables.

Figure 1.

Empirically Assessed Model of Intergenerational Continuity in Antisocial Behavior

Our intergenerational theory (Thornberry, 2005) also hypothesizes that the level of intergenerational continuity and the mediating pathways will differ for mothers and for fathers. In American culture, mothers are cast as the primary parent, and “norms are stricter on the centrality and endurance of the mother-child dyad” (Doherty, Kouneski, and Erickson, 1998). Fathers are more likely to play a secondary role; the father-child relationship is less enduring and more strongly shaped by contextual influences, especially relations with the child’s mother (Doherty, Kouneski, and Erickson, 1998; Furstenberg and Cherlin, 1991). Given the centrality of the parenting role for women, we hypothesize that the association between parental antisocial behavior during adolescence and the child’s antisocial behavior will be stronger and more universal for mothers as compared to fathers. For fathers the level of intergenerational similarity will be conditioned by their contact and involvement with the child. We also hypothesize, given the centrality of the parenting role for women, that family processes such as parenting styles will more fully mediate the impact of adolescent antisocial behavior for mothers as compared to fathers. For fathers other aspects of their adjustment to adult roles, for example, employment and financial stress, will be influential as well.

PREVIOUS STUDIES

Several prospective studies of multiple generations have examined intergenerational continuity in antisocial behavior. Generally, they show that a direct link in externalizing or aggressive behavior is observed between parents and children. In addition, intervening variables, many of which are family-related, help explain the intergenerational link in antisocial behavior. It appears that the strength of the parent-child link in antisocial behavior and the degree to which mediators explain the intergenerational link largely depend on the particular child outcome considered, the particular family-related variables used, and the age ranges for the parent and the child at which measurements are taken.

Evidence about the strength of intergenerational continuity in antisocial behavior is somewhat mixed. Some studies find a strong and consistent intergenerational link for antisocial behavior. For example, Huesmann et al. (1984) found a significant direct link between parent and child aggression at age 8 in a model that also incorporated parent aggression at age 30. Cohen et al. (1998) examined intergenerational patterns in different childhood behaviors, finding significant continuity in children’s inhibited behavior. Using data in three successive generations, Bailey et al. (2006) found that grandparent substance use was significantly related to parent substance use and that components of parent problem behavior at ages 13–14 were significantly related to childhood problem behaviors.

Findings of other studies, however, have found less support for an intergenerational hypothesis. Cohen et al. (1998), for example, found no intergenerational continuity in difficult child behavior, and intergenerational continuity was more consistently observed by Cairns et al. (1998) for cognitive development than aggressive development. Smith and Farrington (2004) found that parents with early conduct problems were no more likely to have children with conduct problems than parents who did not display early behavioral issues, although parent adult antisocial behavior was related to early childhood conduct problems. Hops et al. (2003) showed that parent adolescent externalizing behavior was not significantly correlated with child externalizing behavior, and Conger et al. (2003) found that parent aggression towards a sibling at 14–16 years old was not a statistically significant predictor of child aggression towards a parent between 2 and 4 years of age.

The presence of non-significant or mixed findings should not be taken to mean that assertions of intergenerational continuity are invalid. Frequently, comparisons are made between different outcomes for the parent and child, and at non-comparable ages. Also, studies typically consider just one or two of a broad array of potential antisocial behaviors. These inconsistent findings indicate more the need for attention to be paid to methodological issues than the need for researchers to disregard an intergenerational hypothesis.

The second major focus of the literature is the degree to which potential mechanisms explain intergenerational continuity. Here we look at family processes. Kaplan and Liu (1999) tested continuity of antisocial behavior at ages 9–11 and 12–14 for parents and children respectively, finding a strong intergenerational link in antisocial behavior. Parent childrearing, measured at ages 35–39, reduced the estimate of intergenerational continuity; parent antisocial behavior affected childrearing which, in turn, affected child antisocial behavior. In addition, parent adult psychological distress strongly mediated the intergenerational link in antisocial behavior, and when both childrearing and psychological distress were included the mediating effect of parenting became non-significant. Hops et al. (2003) tested a model that included parent and child externalizing behavior. In this case, parent externalizing behavior was indirectly related to child externalizing behavior through aggressive parenting. Capaldi et al. (2003) report that parent adolescent antisocial behavior is both directly and indirectly, via poor parenting, related to child difficult temperament during toddlerhood.

Intergenerational linkages may differ due to the parent’s gender. Thornberry et al. (2003) compared the parent’s adolescent antisocial behavior with the child’s antisocial behavior. They found a significant direct intergenerational link in antisocial behavior for both mothers and fathers. For mothers, no intergenerational link in antisocial behavior was found to be significant once family factors were included, while a direct intergenerational link was still significant for fathers. Thornberry (2005) considered the link between parent adolescent drug use and the child’s delinquency as reported by teachers, using separate analyses for mothers and fathers. For mothers, only their positive parenting style had a direct effect on the child’s delinquency, mediating the impact of their earlier drug use. For the fathers, however, both stressful life events and negative aspects of parenting affected the child’s delinquency, mediating the impact of their adolescent delinquency.

In general, previous literature suggests that parental antisocial behavior is likely to be a significant risk factor for child antisocial behavior and that aspects of the family, especially parenting behaviors, are likely to be important mediators of that effect. The present paper continues and extends the investigation of these issues.

METHODS

We use data from the Rochester Youth Development Study (RYDS), a longitudinal study designed to investigate the development of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents, which began in 1988. The initial RYDS sample consisted of 1,000 7th and 8th graders selected from the Rochester, New York, public schools in 1988. Subjects were selected to overrepresent high-risk youth in an urban community by stratifying the sample on two dimensions. First, males were oversampled (75% vs. 25%) because they are more likely than females to engage in problem behaviors (Moffitt et al., 2001). Second, students residing in areas of the city with a high resident arrest rate were oversampled since they are at greater risk for involvement in a variety of problem behaviors. The final sample is 68% African American, 17% Hispanic, and 15% White. While it represents the full socioeconomic spectrum in an urban population (Farnworth et al., 1994), it overrepresents poor families; at Wave 1, 33% of the heads of households were unemployed and 40% were receiving welfare.

Phase 1 of the study (which is used in the present analysis) covered the adolescent years, from approximately ages 14–18. The adolescents were interviewed every 6 months between spring 1988 and spring 1992 (Waves 1 to 9) and at Wave 9, 88% were re-interviewed. There is no indication of selective subject loss and detailed descriptions of the sample and of the attrition analysis are presented in Krohn and Thornberry (1999) and Thornberry et al. (2003).

The Rochester Intergenerational Study (RIGS) started in 1999 and added a third generation to the overall design. The focal children are comprised of the first biological child, two years of age or older at the initiation of the study, of each of the original adolescent participants. In addition, in subsequent years we added first-born children who turned two as we move toward the sampling goal, all first-born children.

Of the 1,000 original participants, 543 (177 mothers and 366 fathers) had a child who was eligible to participate in the intergenerational study as of Year 6. Mothers are almost always the child’s primary caregivers, and 97% (172 of 177) agreed to participate in the RIGS. Only 25% to 30% of the RYDS fathers live with the focal child, and many of the non-resident fathers have little if any contact with the child. Despite this, 80% (293 of 366) of the original male subjects with biological children are included in the study. The primary reasons for non-inclusion of RYDS fathers are: the other caretaker refused participation (35.5% of non-participants), the father lost contact with the child and his or her mother (22.6%), or the father refused to participate (33.9%). The fathers who enrolled in the study are not statistically different (p < .05) from those who did not on race/ethnicity, age at the birth of the focal child, high school dropout status, history of maltreatment, number of caretaker changes during adolescence, adolescent drug use and delinquency.

Attrition has been exceptionally low. Focusing on the sample that entered the study in Year 1 (n = 371), 98% (365 of 371) participated in the study at Year 6. Of the 453 who entered the study between Years 1 and 5, 98% (n = 444) were retained at Year 6. These retention rates far exceed the target rates that Hansen et al. (1990) recommend for longitudinal studies of three or more years.

The original RYDS sample is a simple stratified sample with different sampling rates within strata designed to represent a cohort of students in the Rochester public schools when appropriately weighted. The RIGS focuses on the first-born children of the original study participants and, therefore, can be weighted to be representative of the original cohort of Rochester 7th and 8th graders who have since become parents. Sample weights have been constructed as the inverse of the original selection probabilities with minor adjustments to account for attrition and have been normalized to have a mean of one. All analyses presented here are weighted to account for the RYDS sampling design.

Data collection in the RIGS is conducted in annual assessments near the child’s birthday. There are three key participants: the child, the RYDS parent, and the child’s other primary caregiver. In the case of fathers, the other caregivers are almost always (96%) the child’s biological mother. In the case of mothers, the other caregiver varies and includes grandmothers, partners, biological fathers, and others.

The present analysis is limited to data from the first six years of the RIGS, 1999 to 2004. As is true for all intergenerational studies there is a substantial age range for the child participants; at Year 1 they ranged from 2 to 13. Because we expect the child’s age to be important in any analysis, we conduct analyses by age, gathering together the participants of a given age across data collection years. In the present case we include only families that were assessed at least once when the child was between the ages of 4 and 9. Although the number of assessments vary, over three quarters were assessed at least 3 times.

All mothers with a child in this age range are included (n = 148). The fathers are more complex. As mentioned earlier, only 25% to 30% of the fathers live with the child and, of those that do not, they have widely varying degrees of contact with the child (Smith et al., 2005). Some fathers have not seen the child in several years while others care for the child on an almost daily basis. In previous analyses (Thornberry, 2005; Thornberry et al., 2006) we have noted substantial differences, both in levels of intergenerational continuity and in mediating processes, between fathers who live with or are in frequent contact with the child and those who are not. We therefore divide the father sample into two groups. The first, called high-contact fathers, either live with the focal child or average more than weekly physical contact with the child over the study period (n = 197). The contact measure is based on father responses to 4 items asking about the frequency of various types of contact. The remainder, low-contact fathers (n = 79), report less frequent contact with the child. As described below, most of the subsequent analyses are restricted to high-contact fathers.

To address the issue of missing data we created 100 imputed data sets using the MCMC method in SAS PROC MI (SAS Institute, Inc., 2004). We then combined results across imputations to provide parameter estimates for the model in Figure 1, appropriately adjusting standard errors and p-values for the additional uncertainty due to missing data (Little and Rubin, 2002). Because directional hypotheses are presented, one-sided tests are used throughout.

Measures

The measure of the parent’s adolescent antisocial behavior is based on self-report data collected in the original RYDS surveys. Every six months the participants responded to a self-reported delinquency index containing 32 items and a self-reported drug use index containing 8 items covering substances from marijuana to crack cocaine. They were asked if they engaged in the behavior since the last interview and, if they had, how frequently. The measure used here is the cumulative frequency of involvement in delinquency and drug use between Waves 2 and 9 covering the age span of 14 to 18. Previous assessments of these measures (Thornberry and Krohn, 2003) and others in the Rochester project (Thornberry et al., 2003) suggest they have acceptable validity and reliability.

The parent’s age at first birth is also based on their self-reports, either in the RYDS or the RIGS, depending on how old they were at the time of the birth. Rather than including a dichotomous variable like teenaged parent, we use a continuous variable of the actual age. For the fathers, the range at which they had their first child is 16 to 27; for the mothers it is 15 to 27.

Parenting stress is based on a 5-item scale assessing how difficult or stressful the respondent perceives the parenting role to be. It includes such items as “taking care of a child turned out to be more of a hassle than you had expected” and “taking care of a child means you are almost never able to do things that you like to do”. Respondents used a four-point response set from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Cronbach’s alpha is .77.

Parenting behavior is measured by a composite index of three key dimensions of parenting. The first is affective ties to the child based on a 10-item scale adapted from the Hudson Index of Parenting Attitudes (Hudson, 1996); alpha is .77. The second is a RYDS index of monitoring and supervision which asks about such issues as how often the parent knows where the child is and who he or she is with. Finally, we include a 4-item measure of consistency of discipline; alpha is .66. The three parenting measures were combined in a measurement model embedded within the overall structural equation model.*

The final variable, child externalizing behaviors, is based on the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist, a well-known assessment of child problem behaviors with solid psychometric properties (Achenbach, 1991). We rely solely on maternal reports as they are most uniformly available in the data set. Thus, for the children of mothers we use their reports and for the children of fathers we use the other caregiver reports.

Since the Rochester study uses a prospective longitudinal design, proper temporal order can be maintained. The parent’s adolescent antisocial behavior and age at first birth precede the family process variables which are themselves ordered. Parenting stress was measured when the child was 4 to 5 years old and parenting behaviors when the child was 6 to 7 years old. Finally, externalizing problems were assessed when the child was 8 to 9 years old. In each case, scores were averaged across the two year period to create the final measure.

RESULTS

We begin by examining the level of intergenerational continuity in antisocial behavior between parent and child (Table 1). For the mothers there is a significant correlation, r = .32, p < .001. The more frequently the mother engaged in drug use and delinquency during adolescence the higher the rate of her child’s externalizing problems at ages 8–9.

Table 1.

Correlation between Parent Adolescent Antisocial Behavior and Child Antisocial Behavior, by Parent Gender

| Parent Adolescent Drug Use and Delinquency: |

Child Externalizing Problems, age 8–9 |

|---|---|

| Mothers | .32*** |

| High-Contact Fathers | .21** |

| Low-Contact Fathers | .05 |

p < .01;

p < .001

For the fathers, however, the relationship is dependent upon their level of contact with their child. For the high-contact fathers adolescent drug use and delinquency is significantly associated with their child’s behavior, r = .21, p < .01. But for the low-contact fathers the correlation is quite small, r = .05, and not statistically significant. Because of this null finding, and the fact that some key indicators (e.g., monitoring and discipline) are not asked of fathers who rarely see their children, the following analysis is restricted to mothers and high-contact fathers.

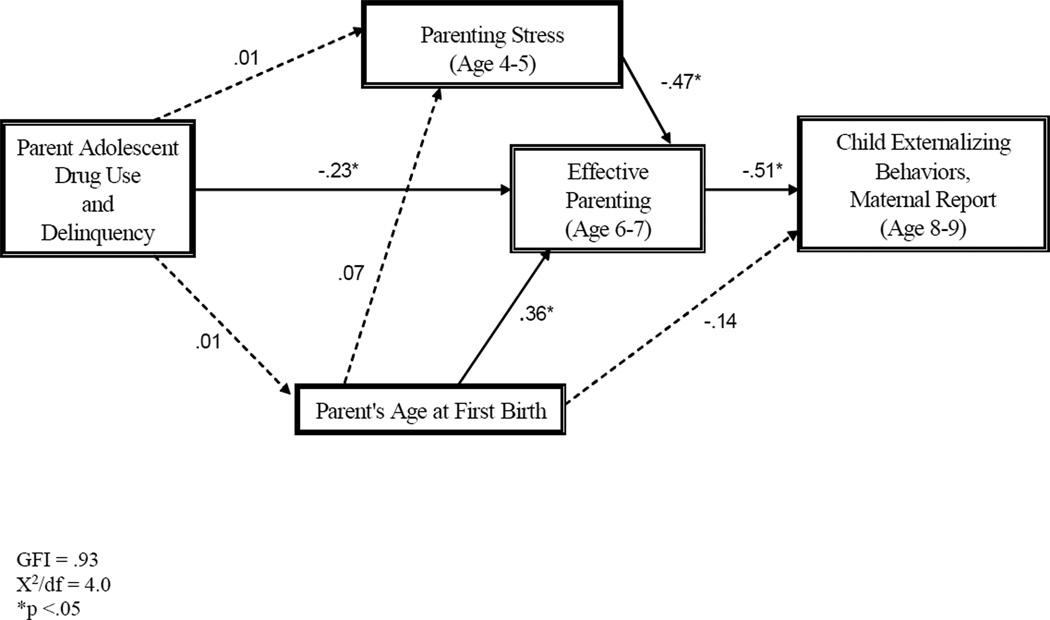

Figure 2 presents the mediational model for the mothers. The model has acceptable fit statistics (GFI = .93;X2/df = 4.0) and indicates the powerful mediating effect of parenting behaviors. Adolescent antisocial behavior is not significantly related to either age at first birth or to perceived levels of parenting stress. It does, however, have a significant negative impact on parenting behaviors; adolescents with a history of drug use and delinquency are more apt to exhibit poor, less effective parenting styles. In addition, mothers who have an earlier onset of parenthood have less effective parenting styles as do mothers who have high levels of parenting stress. In turn, effective parenting is the only variable with a direct effect on the child’s externalizing behavior. As expected, therefore, the mother’s adolescent antisocial behavior has an indirect effect on child antisocial behavior that is mediated by her style of parenting.

Figure 2.

Mediational Model for Intergenerational Continuity in Antisocial Behavior, Mothers Only (standardized coefficients)

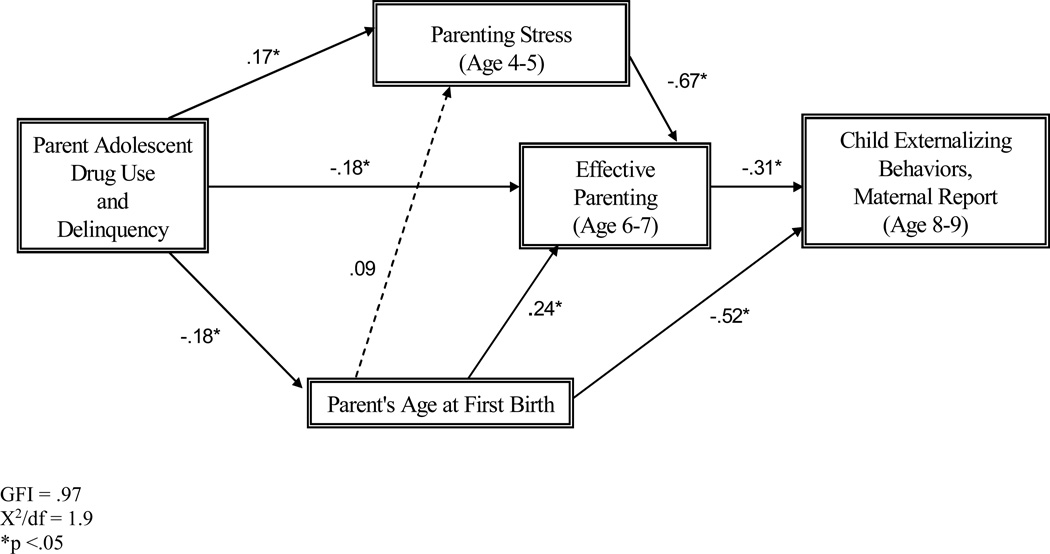

The model for high-contact fathers is presented in Figure 3. This model also has acceptable fit statistics (GFI = .97; X2/df = 1.9). In this case, adolescent antisocial behavior has significant effects on all the mediators. Adolescent drug use and delinquency lead to a lower age at first birth, increase perceived parenting stress, and reduce effective parenting styles. In addition, younger age at first birth reduces effective parenting, as does parenting stress. Both age at first birth and parenting style have direct effects on the child’s externalizing behaviors. Thus for the high-contact fathers there are multiple paths that mediate the impact of adolescent antisocial behavior on the child’s behavior. Involvement in drug use and delinquency during adolescence interferes with subsequent development in several important domains, ultimately creating risk for offspring.

Figure 3.

Mediational Model for Intergenerational Continuity in Antisocial Behavior, High-Contact Fathers Only (standardized coefficients)

DISCUSSION

This article examined the issue of intergenerational continuity in antisocial behavior from a life-course perspective. We find that for parents who have frequent, ongoing contact with their oldest biological child, their adolescent drug use and delinquency create subsequent risk for their children. This was observed for mothers, virtually all of whom live with their child, and for high-contact fathers who live with or see the child at least weekly. Interestingly, this association is not observed for absent fathers who only see the child sporadically. These results are consistent with others from the Rochester study that examined intergenerational patterns of substance use (Thornberry et al., 2006), and together they strongly suggest that continuing contact with the child is almost essential for an intergenerational transfer of risk. If this pattern is maintained as the children age and enter the peak ages of offending, and especially if it is replicated in other studies, it focuses attention on social and environmental factors as likely mediators.

Accordingly, we examined some key mediating processes expected from a life-course perspective. In particular we examined age at first birth, stress associated with the parenting role, and basic parenting behaviors. For the mothers, parenting behaviors (a composite measure of affective ties to the child, monitoring, and discipline) played a dominant role in the model. Effective parenting was compromised by adolescent antisocial behavior, a young age at first birth, and by parenting stress. It was the only variable with a direct effect on the child’s antisocial behavior and it was the key mediator of the impact of parental antisocial behavior. For the high-contact fathers their adolescent antisocial behavior had a more pervasive influence on their later development, reducing their age at first birth, increasing parenting stress, and reducing effective parenting behaviors. Thus, for the fathers there are multiple pathways by which their adolescent antisocial behavior leads to an elevated level of antisocial behavior for their child.

Although this study contributes to our understanding of patterns of intergenerational continuity in antisocial behavior, it is not without its limitations. Given the current sample size of the RIGS we were only able to test a part, albeit a central part, of our overall intergenerational model (Thornberry, 2005). The roles of other important mediators, such as structural adversity and family conflict, need eventually to be added to the investigation. Also, we did not examine differences by child gender, although there is growing evidence of gender similarity in risk processes (Moffitt et al., 2001; Hyde, 2005).

Overall, these results point to the importance of considering two general processes in investigating intergenerational continuity in antisocial behavior. First, we need to systematically consider the role of ongoing contact and involvement with the child. Global assessments, for example, estimating the intergenerational linkage for all parents, or even for all fathers which in our case was significant (r = 21; p < .01), may be quite misleading. Second, and relatedly, we need to recognize that both the level of continuity and the mediating pathways may differ for mothers and fathers. This is evident, both in these results and others based on the Rochester data (e.g., Thornberry et al., 2003; Thornberry, 2005). Identifying similarities, for example the central role of parenting behaviors for both mothers and fathers, as well as differences, for example the strong moderating impact of ongoing contact for fathers, will further our understanding of both paternal and maternal effects on child behavior.

Acknowledgments

Support for this study has been provided by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (86-JN-CX-0007, 96-MU-FX-0014, 2004-MU-FX-0062), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5-R01-DA020195, 5-R01-DA05512), the National Science Foundation (SBR-9123299, SES-9123299), and the National Institute of Mental Health (5-R01-MH56486). Work on this project was also aided by grants to the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the University at Albany from NICHD (P30-HD32041) and NSF (SBR-9512290). Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

To conserve space we do not include these results here. They are available on request.

Contributor Information

Terence P. Thornberry, University of Colorado

Adrienne Freeman-Gallant, University at Albany.

Peter J. Lovegrove, University of Colorado

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychology; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Hill KG, Oesterle S, Hawkins JD. Linking substance use and problem behavior across three generations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:273–292. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Cairns BD, Xie H, Leung MC, Hearne S. Paths across generations: Academic competence and aggressive behaviors in young mothers and their children. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1162–1174. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Pears KC, Patterson GR, Owen LD. Continuity of parenting practices across generations in an at-risk sample: A prospective comparison of direct and mediated associations. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:127–142. doi: 10.1023/a:1022518123387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS, Hartmark C. Behavior patterns of young children and their offspring: A two-generation study. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1202–1206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Neppl T, Kim KJ, Scaramella LV. Angry and aggressive behavior across three generations: A prospective, longitudinal study of parents and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:143–160. doi: 10.1023/a:1022570107457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ, Kouneski EF, Erickson MF. Responsible fathering: An overview and conceptual framework. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH., Jr Lerner RM, Damon W. Handbook of Child Psychology, Volume 1: Theoretical Models of Human Development. New York: Wiley; 1997. The life course and human development; pp. 939–991. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP, Jolliffe D, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M, Kalb L. The concentration of offenders in families, and family criminality in the prediction of boys' delinquency. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:579–596. doi: 10.1006/jado.2001.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Jr, Cherlin AJ. Divided Families: What Happens to Children when Parents Part. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Tobler NA, Graham JW. Attrition in substance abuse prevention research: A meta-analysis of 85 longitudinally followed cohorts. Evaluation Review. 1990;14:677–685. [Google Scholar]

- Hops H, Davis B, Leve C, Sheeber L. Cross-generational transmission of aggressive parent behavior: A prospective, mediational examination. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:161–169. doi: 10.1023/a:1022522224295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson WH. WALMYR Assessment Scales Scoring Manual. Tempe, AZ: WALMYR; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR, Eron LD, Lefkowitz MM, Walder LO. Stability of aggression over time and generations. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:1120–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde JS. The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist. 2005;60:581–592. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KC, Neale MC, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Behavioral genetic confirmation of a life-course perspective on antisocial behavior: Can we believe the results? Behavioral Genetics. 2001;31:456–475. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan HB, Liu X. Explaining transgenerational continuity in antisocial behavior during early adolescence. In: Cohen P, Slomkowski C, Robins LN, editors. Historical and Geographical Influences on Psychopathology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. pp. 163–191. [Google Scholar]

- Krohn MD, Thornberry TP. Retention of minority populations in panel studies of drug use. Drugs & Society. 1999;14:185–207. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd edition. New York: John Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA. Sex Differences in Antisocial Behaviour: Conduct Disorder, Delinquency, and Violence in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SH, Waldman ID. Genetic and environmental influences on antisocial behavior: A meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:490–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, Inc. SAS/Stat 9.1 User’s Guide, Chapter 44: The MI Procedure. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff E. Genetic influences on conduct disorder. In: Hill J, Maughan B, editors. Conduct disorders in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 202–234. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Farrington DP. Continuities in antisocial behavior and parenting across three generations. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 2004;45:230–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CA, Krohn MD, Chu R, Best O. African American fathers: Myths and realities about their involvement with their firstborn children. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:975–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP. Toward an interactional theory of delinquency. Criminology. 1987;25:863–891. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP. Explaining multiple patterns of offending across the life course and across generations. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2005;602:156–195. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Freeman-Gallant A, Lizotte AJ, Krohn MD, Smith CA. Linked lives: The intergenerational transmission of antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:171–184. doi: 10.1023/a:1022574208366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. Comparison of self-report and official data for measuring crime. In: Pepper JV, Petrie CV, editors. Measurement Problems in Criminal Justice Research: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. pp. 43–94. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, Freeman-Gallant A. Intergenerational roots of early onset substance use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2006;36:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Smith CA, Tobin K. Gangs and Delinquency in Developmental Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]