Abstract

Loss of cardiomyocytes (CMs), which lack the innate ability to regenerate, due to ageing or pathophysiological conditions (e.g. myocardial infarction or MI) is generally considered irreversible, and can lead to conditions from cardiac arrhythmias to heart failure. Human (h) pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including embryonic stem cells (ESC) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), can self-renew while maintaining their pluripotency to differentiate into all cell types, including CMs. Therefore, hPSCs provide a potential unlimited ex vivo source of human CMs for disease modelling, drug discovery, cardiotoxicity screening and cell-based heart therapies. As a fundamental property of working CMs, Ca2+ signalling and its role in excitation–contraction coupling are well described. However, the biology of these processes in hPSC-CMs is just becoming understood. Here we review what is known about the immature Ca2+-handling properties of hPSC-CMs, at the levels of global transients and sparks, and the underlying molecular basis in relation to the development of various in vitro approaches to drive their maturation.

Since non- or lowly regenerative adult cardiomyocytes (CMs) lack an innate clinically relevant ability to regenerate, their significant loss due to ageing or pathophysiological conditions (e.g. myocardial infarction or MI) can have lethal consequences by hastening the progression of heart failure (HF, primarily a disease of the ventricle) and/or predisposing to conduction abnormalities and arrhythmias. Current therapeutic regimes are palliative in nature, and in the case of end-stage HF, heart transplantation remains the last and only resort. Since this option is severely limited by the number of available donor organs, cell replacement therapy presents a laudable alternative for myocardial repair. Unfortunately, however, it is also limited by the availability of transplantable human CMs (e.g. human fetal CMs) due to practical and ethical considerations. As a result, transplantation of non-cardiac cells such as skeletal muscle myoblasts (SkMs), smooth muscle cells and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) has been sought as a potentially viable alternative. However, the non-cardiac identity of these cell sources has presented major limitations. In the case of SkMs, their lack of electrical integration after transplantation into the myocardium has been shown to underlie the generation of malignant ventricular arrhythmias, leading to the premature termination of their clinical trials. As for bone marrow stem cells, it is now well established that they lack the capacity to transdifferentiate into cardiac muscle (Murry et al. 2004), limiting their utility for myocardial repair. Indeed, various cardiac and non-cardiac lineages, as well as embryonic and adult stem cell populations, have been investigated as potential sources, with their pros and cons extensively reviewed elsewhere (Menasche et al. 2003; Smits et al. 2003; Murry et al. 2004; Sil et al. 2004; Kong et al. 2010; Poon et al. 2011). This review focuses on human (h) pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) that have been shown to generate genuine human CMs, with an emphasis on their Ca2+-handling properties.

Human pluripotent stem cells – embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells

Upon fertilization of an oocyte by sperm, the resultant zygote, which possesses the total potential (i.e. totipotency) to develop into all cell types including those necessary for embryonic development (such as extra-embryonic tissues), undergoes several rounds of cell division to become a compact ball of totipotent cells known as the morula. As the morula continues to grow (∼4 days after fertilization), its cells migrate to form a more specialized hollow, fluid-filled structure known as the blastocyst consisting of an outer cell layer, the trophectoderm, and an inner cluster of cells collectively known as the inner cell mass (ICM). While the trophectoderm is committed to developing into extra-embryonic structures for supporting fetal development, the ICM that retains the ability to form any cell of the body except the placental tissues (i.e. pluripotency) will give rise to the embryo. Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are isolated from the ICM. ESCs possess the ability to remain undifferentiated and propagate in vitro while maintaining their normal karyotype and pluripotency to differentiate into all the three embryonic germ layers (i.e. endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm) as well as their lineage derivatives including brain, blood, pancreatic, heart and other muscle cells. Pluripotent mammalian ESC lines were first derived from rodent blastocysts 30 years ago (Evans & Kaufman, 1981; Martin, 1981), leading to the generation of the first transgenic animal and thereby revolutionizing genetics and disease modelling; the human counterpart was first successfully isolated about a quarter century later (Thomson et al. 1998). As an alternative, direct reprogramming of adult somatic cells to become hES-like induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has been developed. Forced expression of four pluripotency genes, Oct3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4 (Takahashi & Yamanaka, 2006; Meissner et al. 2007; Takahashi et al. 2007), or Lin28 (Yu et al. 2007) suffices to reprogramme fibroblasts into iPSCs. Recent studies have further demonstrated the successful use of fewer pluripotency factors (Huangfu et al. 2008; Kim et al. 2008; Nakagawa et al. 2008) and non-viral methods (e.g. with synthetic modified RNA; Warren et al. 2010). Although concerns such as induced somatic coding mutations (Gore et al. 2011) and immunogenicity (Zhao et al. 2011) have yet to be fully addressed, human (h) iPSC largely resemble hESCs in terms of their pluripotency, surface markers, global transcriptomic profile, and can likewise be differentiated into CMs. Therefore, hESC/iPSC-CMs serve well as a potential unlimited ex vivo source of human CMs for disease modelling, drug discovery, cardiotoxicity screening and cell-based heart therapies.

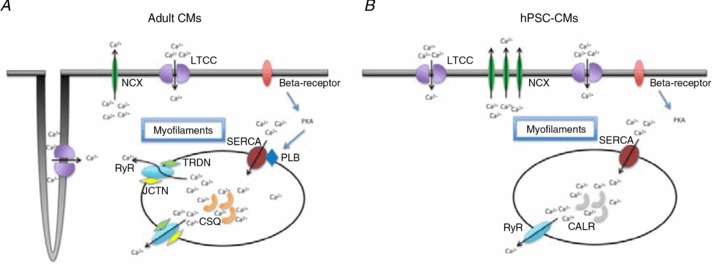

Ca2+ cycling and excitation–contraction (EC) coupling as a fundamental property of working CMs

During an action potential (AP) of adult ventricular (V) CMs, membrane depolarization leads to the opening of sarcolemmal voltage gated L-type Ca2+ (ICa,L) channels (a.k.a. dihydropyridine receptors, DHPR), which are localized at the invaginations of the T-tubular network, in close spatial proximity to the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), in which a large internal pool of Ca2+ is stored. Ca2+ entry through ICa,L channels activates a positive feedback process termed as Ca2+-induced-Ca2+ release (CICR; Bers, 2002) that triggers the release of SR Ca2+ via the ryanodine receptors (RyRs), escalating the cytosolic Ca2+ and resulting in tropomyosin translocation and myofilament contraction. For relaxation, elevated Ca2+ gets pumped back into the SR by the sarcoplasmic–endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and extruded to the extracellular space by the electrogenic Na+–Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) to return to the resting Ca2+ level. Such a rise and subsequent decay of Ca2+, known as the Ca2+ transient, modulates both the contractile force (inotropy) and frequency (chronotropy) of CM contraction. Indeed, Ca2+-handling abnormalities due to malfunction of EC coupling proteins can be arrhythmogenic. As examples, SERCA2a down-regulation, hyper-phosphorylation and enhanced leak of RYR2, NCX up-regulation all lead to Ca2+ cycling defects. The process of EC coupling is schematically summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Schematic comparison of Ca2+ signalling pathways in adult and hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes.

In both adult (A) and hPSC-CMs (B), Ca2+ entry via ICaL triggers Ca2+ release from SR via RyRs, leading to the rise of Ca2+ transient; the subsequent decay is similarly accomplished by Ca2+ reuptake and extrusion via SERCA and NCX, respectively. The smaller amplitude and slower kinetics and null inotropic response of hPSC-CMs compared to adult can be attributed to the following differences: (1) lack of junction (JCTN) and triadin (TRDN) to facilitate RyR function in hPSC-CMs; (2) lack of calsequestrin (CSQ) for SR Ca buffering (rather, calreticulin (CALR) is expressed in hPSC-CMs); (3) lack of phospholamban (PLB) for sarcoplasmic–endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) modulation; (4) lower SERCA and RyR expression in hPSC-CMs; (5) lack of T-tubules which contributes to a U-shape of Ca2+ propagation wavefront.

In addition to ICa,L, RyR, SERCA and NCX, Ca2+ homeostasis also depends on an array of accessory Ca2+-handling proteins. RyRs are coupled to triadin (TRDN), junctin (JCTN) and calsequestrin (CSQ) at the luminal SR surface (Zhang et al. 1997). As the most abundant, high-capacity but low-infinity Ca-binding protein in the SR, the cardiac isoform CSQ2 can store up to 20 mm Ca2+ while buffering the free SR [Ca2+] at ∼1 mm (Beard et al. 2004), allowing repetitive muscle contractions without run-down. CSQ2 also coordinates the rates of SR Ca2+ release and loading by modulating RyR activities. In fact, the SR Ca2+ content affects the amount of Ca2+ released via CICR (Bassani et al. 1995; Shannon et al. 2000). For a given ICa,L trigger, a high SR Ca2+ load enhances the open probability of RyRs while directly providing more Ca2+ available for release (Lukyanenko et al. 1996). By contrast, ICa,L can no longer cause CICR when the SR Ca2+ content is sufficiently low. Mechanistically, CSQ2 senses the levels of luminal Ca2+ and effects RyRs via TRDN and JCTN. For instance, when SR Ca2+ declines (during Ca2+ release), an increase of Ca2+-free CSQ2 deactivates RyRs by binding via JCTN and TRDN; alternatively, SR Ca2+ reload (upon relaxation when CICR terminates) relieves the CSQ2-mediated inhibition of RyRs (Beard et al. 2004; Gyorke et al. 2004). Thus, CSQ2 is an important determinant of the SR load. For β-adrenergic signalling, the cascade involves such components as β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs), the Gs protein–adenylyl cyclase (AC) and protein kinase A (PKA). PKA phosphorylates such substrates as ICa,L, RyR, PLB, troponin I, myosin binding protein-C (MyBP-C) and protein phosphatase inhibitor-1 to increase Ca2+ influx, Ca2+ cycling and myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, thereby augmenting contractility (Zhao et al. 1994; Sulakhe & Vo, 1995; Gerhardstein et al. 1999; Kunst et al. 2000; Marx et al. 2000; Zhang et al. 2002; MacLennan & Kranias, 2003).

In mature ventricular CMs (VCMs), CICR is also optimized by the presence of T-tubules, invaginations in the sarcolemmal membrane that concentrates ICa,L channels in close spatial proximity to RyRs (Brette & Orchard, 2003, 2007). With a minimized Ca2+ diffusion distance between ICa,L and RyRs, SR deep in VCMs with large cross-sectional area can participate in CICR without significant time lags. This increased efficiency is demonstrated by a uniform increase in cytosolic Ca2+ across the transverse section of the cell (with simultaneous recruitment of all SRs). Such a uniform Ca2+ wave, with peripheral and central Ca2+ transients having similar amplitudes and kinetics, starkly contrasts the U-shaped Ca2+ wave propagation in de-tubulated CMs (Brette & Orchard, 2003). The U-shaped waves result from a time delay that is proportional to the diffusion distance squared in recruiting the Ca2+ stores at the cell centre (Song et al. 2005). Fast and synchronized activation of RyR translates into a larger Ca2+ transient amplitude, recruitment of more actin–myosin cross-bridge cycling, and generation of greater contractile force (Brette & Orchard, 2003; Louch et al. 2004).

Taken collectively, proper Ca2+-handling properties of hESC/iPSC-CMs are therefore crucial for their clinical and other applications. Transplantation of cells with improper Ca2+-handling and electrophysiological properties could introduce sources of Ca2+-mediated afterdepolarizations and/or automaticity which in turn result in various forms of potentially lethal arrhythmias.

Cardiac differentiation of hPSCs and heterogeneity

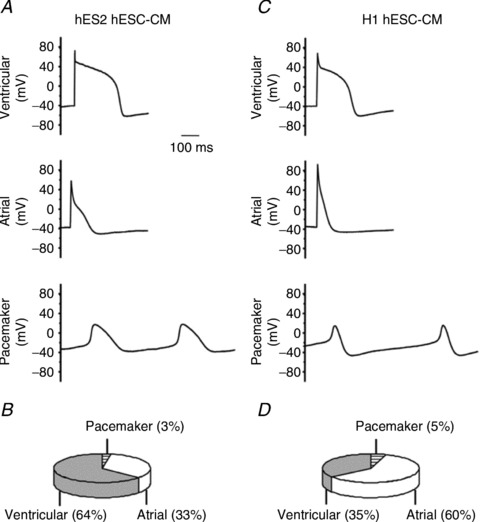

The natural development of the heart is one of the earliest and most essential steps during vertebrate embryonic development (Musunuru et al. 2010). For in vitro differentiation, PSCs can spontaneously form 3-D aggregates called embryoid bodies (EBs) with a variety of specialized cell types including CMs (Kehat et al. 2001; Xu et al. 2002; He et al. 2003; Xue et al. 2005). Different PSC lines display distinct cardiogenic potentials to become early ventricular-, atrial- and pacemaker-like derivatives as gauged by their signature AP profiles (Moore et al. 2008). For instance, compared to H1, HES2 cells have a higher likelihood of differentiating into ventricular-like hESC-CMs (Fig. 2). The cardiogenicity of PSCs is also highly influenced by a number of factors such as the EB size, media composition (e.g. serum, cytokines), the time and duration of differentiation, etc. Recently, various directed cardiac differentiation protocols (Yang et al. 2008; Zhu et al. 2010; Kattman et al. 2011; Ren et al. 2011; Lian et al. 2012; Minami et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2012) have been developed to enable the derivation of PSC-CMs in large quantities with yields orders of magnitude higher than the traditional method of EB formation (Kehat et al. 2001). Despite the improved yields, the resultant cell population continues to be heterogeneous. Various purification methods including Percoll gradient centrifugation (Xu et al. 2002), optical signatures (Chan et al. 2009), second harmonic generation (Awasthi et al. 2012) and genetic selection based on the expression of a reporter protein under the transcriptional control of a cardiac-restricted promoter (e.g. α–MHC: Anderson et al. 2007; MLC2v: Huber et al. 2007; Fu et al. 2010) have been developed to generate purer CM preparations.

Figure 2.

Action potentials of ventricular, atrial and pacemaker cardiomyocytes derived from HES2 (A) and H1 hESCs (C). The corresponding pie charts (B and D). Adapted from Moore et al. (2008).

Functional but immature Ca2+ handling of hPSC-CMs

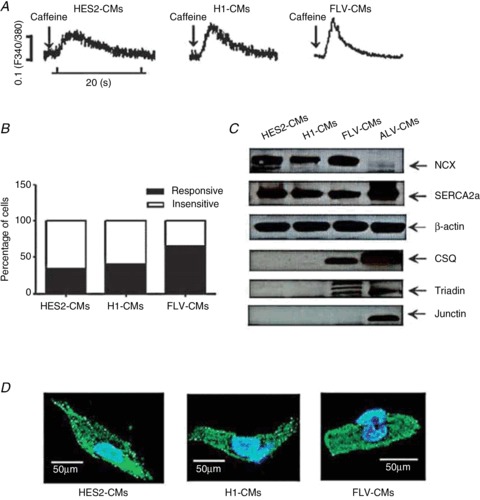

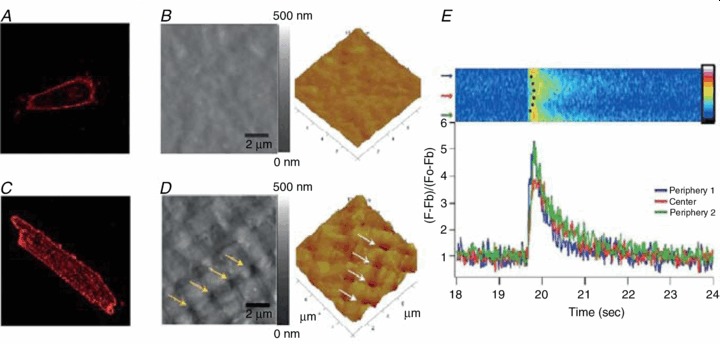

In murine (m) ESC-CMs, both the SR load and RyR are essential for regulating contractions even at very early developmental stages (Fu et al. 2006a,b). Similarly, Ca2+ transients have been recorded from hESC-CMs as beating clusters (Dolnikov et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2007) or single cells (Fu et al. 2010). In brief, Ca2+-handling properties of hESC-CMs resemble those of human fetal left ventricular (LV) CMs (16–18 weeks) but significantly differ from adult LVCMs. Upon electrical stimulation, hESC-CMs elicit Ca2+ transients with much smaller amplitudes and slower kinetics compared to adult (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Pharmacologically, ∼40% are responsive to caffeine (Liu et al. 2007). The responsiveness of hESC-CMs to caffeine are also reported in other studies (Satin et al. 2008; Zhu et al. 2009). Ryanodine reduces the electrically evoked Ca2+ transient amplitudes and slows the upstroke of caffeine-responsive but not -insensitive hESC-CMs. Thapsigargin, a SERCA inhibitor, similarly reduces the amplitude and slows the decay of only caffeine-responsive hESC-CMs(Liu et al. 2007). NCX is functional (Fu et al. 2010), with its expression highest in hESC-CMs but intermediate in fetal and lowest in adult LVCMs. Although SERCA2a expression is most robust in adult LVCMs, it is already substantially and comparably expressed in hESC- and fetal LVCMs. RyRs are expressed in hESC-CMs and fetal LVCMs, but lack the organized pattern seen in adult due to the lack of T-tubules. On the far end, the regulatory proteins junctin, triadin, and calsequestrin (CSQ) are robustly expressed in adult LVCMs but completely absent in hESC-CMs. Consistent with the lack of T-tubules, the Ca2+ wavefront of hESC-CMs is U shaped (Fig. 4), indicating a time delay in activation of RyRs at the centre but faster and greater magnitude of Ca2+ transient increase at the periphery. Furthermore, a negative force–frequency relationship that is different from adult but typical of immature CMs has been reported (Dolnikov et al. 2006; Turnbull et al. 2013). These key differences from adult CMs are summarized in Fig 1 and Table 1.

Figure 3. Functional yet immature Ca2+ handling in hESC-CMs compared with fetal ventricular CMs (FLV-CMs) and adult ventricular CMs (ALV-CMs).

A, caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient in HES2-CMs, H1-CMs and FLV-CMs. B, percentage of respective CMs that are sensitive to caffeine treatment. C, Ca2+-handling protein expression profile in HES2-CMs, H1-CMs, FLV-CMs and ALV-CMs. D, immunostaining of ryanodine receptors in HES2-CMs, H1-CMs and FLV-CMs. Adapted from Liu et al. (2007).

Table 1.

Expression levels of Ca2+-handling proteins, and Ca2+ transient properties in hESC-CMs, fetal LVCMs and adult LVCMs

| hESC-CMs | Fetal LVCMs | Adult LVCMs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expression levels of Ca2+-handling proteins | RyR | ++ | ++ | ++++ |

| SERCA | +++ | +++ | ++++ | |

| Phospholamban | – | ++ | ++++ | |

| CSQ/TRDN/JCTN | – | + | ++++ | |

| NCX | +++ | ++++ | + | |

| Ca2+ transient properties | Basal [Ca2+]i | ++ | +++ | ++++ |

| Amplitude | ++ | ++ | ++++ | |

| Decay | ++ | ++ | ++++ | |

| Upstroke | ++ | ++ | ++++ |

Adapted from Kong et al. (2010).

Figure 4. Absence of T-tubules in hESC-CMs.

Di-8-ANEPPS staining shows no intracellular fluorescent spots in hESC-CMs (A) compared with adult cardiomyocytes (C). B and D, Atomic force microscopy imaging reveals no T-tubules, present as regularly spaced pores, in hESC-CMs. E, lack of T-tubules results in a non-uniform, U-shaped Ca2+ transient. Adapted from Lieu et al. (2009).

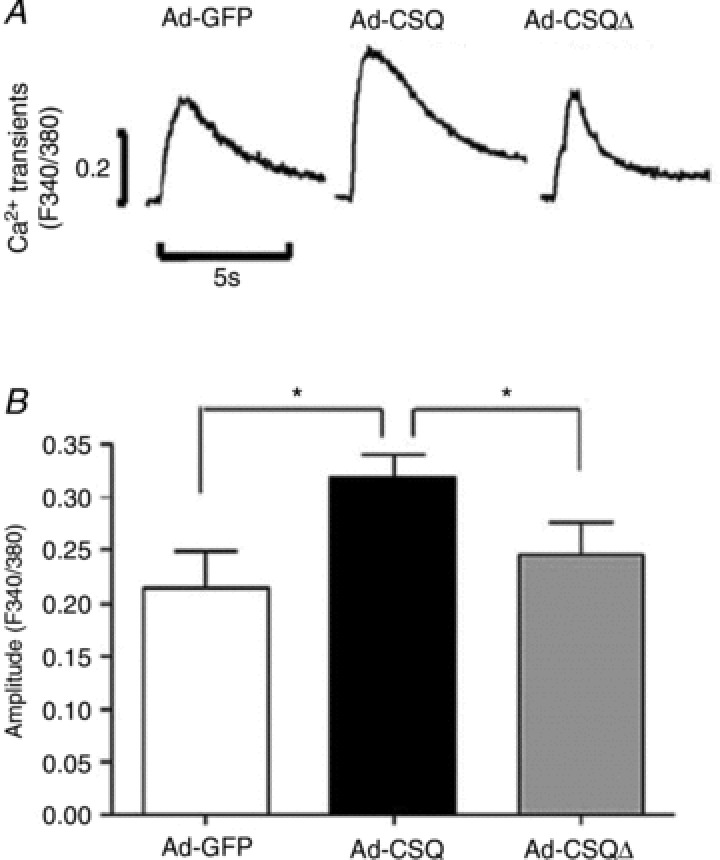

Immature Ca2+ transient properties of hESC-CMs can be attributed to the differential developmental expression profiles of specific Ca2+-handling proteins in hESC-CMs compared to adult. Gene transfer of CSQ that is otherwise absent in hESC-CMs significantly increases the transient amplitude, upstroke and decay velocities, as well as both the SR Ca2+ load and elevated basal cytosolic Ca2+ (Fig. 5), but without altering ICa,L, suggesting that the improved transient is not simply due to a higher Ca2+ influx for CICR.

Figure 5. CSQ overexpression increases the amplitude of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient.

A, representative caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient tracings for Ad-GFP, Ad-CSQ and Ad-CSQΔ transduced hESC-CMs. B, bar graphs of amplitude. *P < 0.05. Adapted from Liu et al. (2009).

Ca2+ sparks in hPSC-CMs

Global Ca2+ transient is crucial for CM contraction; but, Ca2+ signals can be highly localized, with Ca2+ release units (CRU) being clusters of Ca2+ release channels (RyRs, inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) or a mixture) located on the SR membrane (Cheng & Lederer, 2008). Discrete> local Ca2+ release through RyRs has been termed ‘Ca2+ sparks’. Ca2+ waves form when Ca2+ release from CRU is regenerative, typically reflecting the high sensitivity of CICR (Keizer et al. 1998; Izu et al. 2001; Cheng & Lederer, 2008). Ca2+ sparks are the elementary events of EC coupling: electrical stimulation triggers thousands of Ca2+ sparks that spatio-temporally summate to increase the level of cytoplasmic Ca2+ level, thereby causing contractions (Cheng et al. 1993, 1996). In murine embryonic CMs, sparks are largely limited to area around the nucleus (Janowski et al. 2006). By contrast, those of adult ventricular and atrial cells are near the sarcolemma (Janowski et al. 2006). In mESC-CMs, it has been reported that Ca2+ sparks and spontaneous activity are essentially dependent on RyR2 (Itzhaki et al. 2006). Ca2+ sparks in mESC-CMs are absent in very early cardiac progenitors, but markedly increase in their frequency along with increased RyR expression at later stages (Sauer et al. 2001). In hESC-CMs (unsorted), both RyR2 and IP3R have been shown to contribute to the generation of Ca2+ sparks (Satin et al. 2008; Sedan et al. 2008; Itzhaki et al. 2011). In general, spontaneous Ca2+ sparks with smaller peak amplitude, slower kinetics and lower frequency compared to fetal LVCMs have been reported to localize to the surface membrane (Guan et al. 2007; Zhu et al. 2009). In our laboratory, hESC-VCMs, selected on the basis of dual expression of a fluorescent reporter (e.g. tdTomato) and zeocin resistance under the transcriptional regulation of the ventricle-specific promoter MLC2v and derived using our ventricular specification protocol, have similar Ca2+ spark parameters, although sub-cellular localization to around the nucleus or near the sarcolemma is not observed; rather, Ca2+ sparks occur readily throughout the cytoplasm (Awasthi et al. 2012).

β-Adrenergic responses in hESC-CMs

β-Adrenergic signalling figures prominently in the modulation of cardiac function. Upon its stimulation via β-ARs by their agonists, the heart rate, contractile force and AP conduction velocity (dromotropy) increase thereby escalating the total cardiac output. Several reports show that β-adrenergic stimulation by isoproterenol (Iso) hastens the spontaneous contraction or AP firing and conduction of hESC-CM (Xue et al. 2005; Sedan et al. 2008; Burridge et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2013). When stimulated by Iso, however, engineered human cardiac tissues strips made of hESC-VCMs exhibit a positive chronotropic response by increasing their spontaneous contraction frequency, but without an inotropic effect (i.e. no increase in contractile force; Turnbull et al. 2013). Consistently, Iso increases AP firing but not the transient amplitude in single hESC-VCMs (G. Chen & R. A. Li, unpublished data). Similar observations have been made using unsorted multi-cellular hESC-CM clusters (Pillekamp et al. 2012). Phospholamban (PLB) is an inhibitor of SERCA in its unphosphorylated form, and a critical determinant of contractility and inotropic responses (MacLennan & Kranias, 2003). Once its primary site Ser-16 gets phosphorylated by PKA, its inhibitory effect on SERCA is reversed, leading to acceleration of Ca2+ sequestration into the SR and hastening cardiac relaxation. Interestingly, overexpression of PLN which is poorly expressed in hESC-CMs restores the positive ionotropic response of hESC-VCMs to Iso (G. Chen & R. A. Li, unpublished data).

iPSC-based modelling of Ca2+-handling defects

Patient-specific iPSCs have been generated to model various forms of Ca2+-handling genetic defects. To give a few examples, hiPSC-CMs derived from catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) patients with a missense mutation D307H in CSQ2 have been shown to display arrhythmogenicity in response to β-adrenergic stimulation (Novak et al. 2012). Similarly, CPVT-iPSC-CMs that carry the RYR2 mutations S406L (Jung et al. 2012), M4109R (Itzhaki et al. 2012) or P2328S (Kujala et al. 2012) exhibit increased susceptibility to arrhythmogenic events such as delayed after-depolarizations (DADs) when subjected to catecholaminergic stress as a result of their changes in Ca2+ spark and transient properties. As for iPSCs derived from a familial dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) patient with the cardiac troponin T point mutation R173W, their CMs have altered Ca2+ homeostasis, decreased contractility, and abnormal distribution of sarcomeric α-actinin but functional improvements are seen after beta-blocker treatment or Serca2a overexpression (Sun et al. 2012).

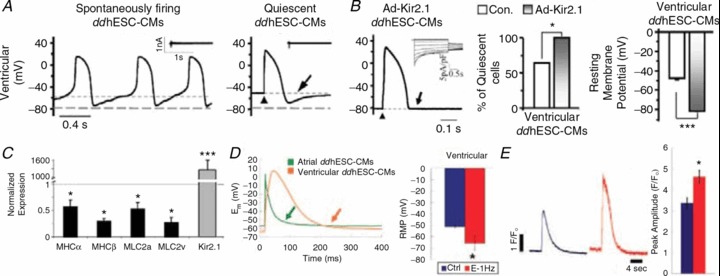

Driven maturation by in vitro electrical conditioning

Other than Ca2+ handling, the electrophysiological properties of PSC-CMs are also immature (Kehat et al. 2002; Sartiani et al. 2007; Poon et al. 2011). Adult LVCMs are normally electrically silent yet excitable upon stimulation. By contrast, hESC-VCMs display significant automaticity, depolarized resting membrane potential (RMP), phase 4 depolarization and delayed after-depolarization (DAD) that are not seen in adult VCMs (Lieu et al. 2012; Fig. 6A). Long-term (>120 days) culturing leads to some but still limited structural and functional maturation (Lundy et al. 2013). While we and others have shown that when transplanted such AP-firing hESC-CMs can serve as an epicardial source of automaticity and cause potential arrhythmias (Kehat et al. 2004; Xue et al. 2005), it has been recently reported that their transplantation in injured hearts can suppress electrical disturbances (Shiba et al. 2012). For transplantation of murine fetal cardiomyocytes, physiological but immature AP properties are found in transplanted cells surrounded by cryoinjured tissue (Halbach et al. 2007). Among the panoply of sarcolemmal ionic currents investigated (INa+/ICaL+/IKr+/INCX+/If+/Ito+/IK1−/IKs−), we recently pinpointed the lack of the Kir2.1-encoded inwardly rectifying K+ current (IK1) as the single mechanistic contributor to the immature electrophysiological properties in hESC-CMs (Lieu et al. 2012). Forced expression of Kir2.1 in hESC-CMs completely ablates all the pro-arrhythmic AP traits, rendering the electrophysiological phenotype indistinguishable from adult (Fig. 6B). Despite electrical maturation, Ca2+-handling properties remain immature with smaller transient amplitudes and slow kinetics. Indeed, the expression levels of sarcomeric genes, such as MHCα, MHCβ, MLC2a and MLC2v, of Kir2.1-silenced cells even deteriorate due to the lack of spontaneous contractions after electrical silencing (Fig. 6C). Based on these results, we have further developed a bio-mimetic culturing strategy for enhancing maturation. In vitro electrical conditioning of hESC-CMs promotes electrophysiological maturation (Fig. 6D); pacing-induced regular contractions likewise facilitate maturation of Ca2+-handling and contractile properties with augmented Ca2+ transient and SR Ca2+ load (Fig. 6E). Consistently, the expression levels of CSQ, JCTN, and TRDN (Liu et al. 2007), as well as the T-tubule biogenesis proteins caveolin-3 (Cav3) and amphiphysin-2 (Amp2), which are typically absent or barely expressed in hESC-CMs, all increase. We conclude that key environmental cues are missing in conventional culturing methods, leading to the immaturity of hESC-CMs.

Figure 6. Adenovirus-mediated Kir2.1 overexpression led to hESC-CMs maturation.

A, representative tracings of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes produced by directed differentiation protocol (ddhESC-CMs), showing action potentials (APs) of spontaneously firing (left) and quiescent (right) ventricular CMs. Arrow indicates phase 4-like depolarization. B, APs of Ad-Kir2.1-transduced ventricular ddhESC-CMs. Ik1 in inset. The phase 4-like depolarization was eliminated (arrow) by Ad-Kir2.1 transduction (left). The percentage of quiescent ventricular ddhESC-CMs increased significantly to 100% after Ad-Kir2.1 transduction (middle). Resting membrane potentials (RMPs) of Ad-Kir2.1-transduced ventricular ddhESC-CMs became significantly hyperpolarized relative to control (right). C, after Ad-Kir2.1 transduction, the mRNA expression of contractile elements is significantly reduced relative to control hESC-CMs. D, both electrically conditioned atrial and ventricular ddhESC-CMs harboured action potentials without phase 4-depolarization (left). More hyperpolarized resting membrane potential (RMP) was shown (right). E, caffeine-elicited Ca2+ transients from control (blue) and electrically conditioned (red) ddhESC-CMs, and their averaged peak amplitude were also presented in bar graph. Adapted from Lieu et al. (2012).

Conclusion

The field of regenerative medicine is hampered by an incomplete understanding of mechanisms that underlie the proper maturation of CMs derived from hPSC. As fundamental properties of working CMs, the electrophysiological and Ca2+-handling properties of hESC/iPSC-CMs are just becoming understood. Such knowledge will lead to better tools (e.g. for accurate disease modelling, drug discovery and cardiotoxicity screening) and novel effective approaches for cell-based therapies by improving both the efficacy and survival of hPSC-VCMs after transplantation.

Acknowledgments

None declared.

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Grant Council (T13-706/11), SCRMC and Faculty Cores of HKU.

References

- Anderson D, Self T, Mellor IR, Goh G, Hill SJ, Denning C. Transgenic enrichment of cardiomyocytes from human embryonic stem cells. Mol Ther. 2007;15:2027–2036. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi S, Matthews DL, Li RA, Chiamvimonvat N, Lieu DK, Chan JW. Label-free identification and characterization of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes using second harmonic generation (SHG) J Microscopy Biophoton. 2012;5:57–66. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201100077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassani JWM, Yuan WL, Bers DM. Fractional SR Ca release is regulated by trigger Ca and SR Ca content in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1995;268:C1313–C1319. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.5.C1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard NA, Laver DR, Dulhunty AF. Calsequestrin and the calcium release channel of skeletal and cardiac muscle. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2004;85:33–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM. Cardiac excitation–contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brette F, Orchard C. T-tubule function in mammalian cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2003;92:1182–1192. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000074908.17214.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brette F, Orchard C. Resurgence of cardiac T-tubule research. Physiology. 2007;22:167–173. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00005.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge PW, Thompson S, Millrod MA, Weinberg S, Yuan XA, Peters A, Mahairaki V, Koliatsos VE, Tung L, Zambidis ET. A universal system for highly efficient cardiac differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells that eliminates interline variability. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan JW, Lieu DK, Huser T, Li RA. Label-free separation of human embryonic stem cells and their cardiac derivatives using raman spectroscopy. Anal Chem. 2009;81:1324–1331. doi: 10.1021/ac801665m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Lederer MR, Xiao RP, Gomez AM, Zhou YY, Ziman B, Spurgeon H, Lakatta EG, Lederer WJ. Excitation–contraction coupling in heart: New insights from Ca2+ sparks. Cell Calcium. 1996;20:129–140. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(96)90102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks – elementary events underlying excitation–contraction coupling in heart-muscle. Science. 1993;262:740–744. doi: 10.1126/science.8235594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HP, Lederer WJ. Calcium sparks. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1491–1545. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolnikov K, Shilkrut M, Zeevi-Levin N, Gerecht-Nir S, Amit M, Danon A, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Binah O. Functional properties of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: Intracellular Ca2+ handling and the role of sarcoplasmic reticulum in the contraction. Stem Cells. 2006;24:236–245. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu JD, Jiang P, Rushing S, Liu J, Chiamvimonvat N, Li RA. Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is a determinant of excitation-contraction coupling in human embryonic stem cell-derived ventricular cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:773–782. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu JD, Li J, Tweedie D, Yu HM, Chen L, Wang R, Riordon DR, Brugh SA, Wang SQ, Boheler KR, Yang HT. Crucial role of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in the developmental regulation of Ca2+ transients and contraction in cardiomyocytes derived from embryonic stem cells. FASEB J. 2006a;20:181–183. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4501fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu JD, Yu HM, Wang R, Liang J, Yang HT. Developmental regulation of intracellular calcium transients during cardiomyocyte differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006b;27:901–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardstein BL, Puri TS, Chien AJ, Hosey MM. Identification of the sites phosphorylated by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase on the beta2 subunit of L-type voltage-dependent calcium channels. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10361–10370. doi: 10.1021/bi990896o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore A, Li Z, Fung HL, Young JE, Agarwal S, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Canto I, Giorgetti A, Israel MA, Kiskinis E, Lee JH, Loh YH, Manos PD, Montserrat N, Panopoulos AD, Ruiz S, Wilbert ML, Yu J, Kirkness EF, Izpisua Belmonte JC, Rossi DJ, Thomson JA, Eggan K, Daley GQ, Goldstein LS, Zhang K. Somatic coding mutations in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:63–67. doi: 10.1038/nature09805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan K, Wagner S, Unsold B, Maier LS, Kaiser D, Hemmerlein B, Nayernia K, Engel W, Hasenfuss G. Generation of functional cardiomyocytes from adult mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Circ Res. 2007;100:1615–1625. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000269182.22798.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorke I, Hester N, Jones LR, Gyorke S. The role of calsequestrin, triadin, and junctin in conferring cardiac ryanodine receptor responsiveness to luminal calcium. Biophys J. 2004;86:2121–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74271-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbach M, Pfannkuche K, Pillekamp F, Ziomka A, Hannes T, Reppel M, Hescheler J, Muller-Ehmsen J. Electrophysiological maturation and integration of murine fetal cardiomyocytes after transplantation. Circ Res. 2007;101:484–492. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He JQ, Ma Y, Lee Y, Thomson JA, Kamp TJ. Human embryonic stem cells develop into multiple types of cardiac myocytes – Action potential characterization. Circ Res. 2003;93:32–39. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000080317.92718.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huangfu D, Osafune K, Maehr R, Guo W, Eijkelenboom A, Chen S, Muhlestein W, Melton DA. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from primary human fibroblasts with only Oct4 and Sox2. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1269–1275. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber I, Itzhaki I, Caspi O, Arbel G, Tzukerman M, Gepstein A, Habib M, Yankelson L, Kehat I, Gepstein L. Identification and selection of cardiomyocytes during human embryonic stem cell differentiation. FASEB J. 2007;21:2551–2563. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5711com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki I, Maizels L, Huber I, Gepstein A, Arbel G, Caspi O, Miller L, Belhassen B, Nof E, Glikson M, Gepstein L. Modeling of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia with patient-specific human-induced pluripotent stem cells. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:990–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki I, Rapoport S, Huber I, Mizrahi I, Zwi-Dantsis L, Arbel G, Schiller J, Gepstein L. Calcium handling in human induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaki I, Schiller J, Beyar R, Satin J, Gepstein L. Calcium handling in embryonic stem cell-derived cardiac myocytes – of mice and men. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1080:207–215. doi: 10.1196/annals.1380.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izu LT, Wier WG, Balke CW. Evolution of cardiac calcium waves from stochastic calcium sparks. Biophys J. 2001;80:103–120. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75998-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowski E, Cleemann L, Sasse P, Morad M. Diversity of Ca2+ signalling in developing cardiac cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1080:154–164. doi: 10.1196/annals.1380.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung CB, Moretti A, Mederos y Schnitzler M, Iop L, Storch U, Bellin M, Dorn T, Ruppenthal S, Pfeiffer S, Goedel A, Dirschinger RJ, Seyfarth M, Lam JT, Sinnecker D, Gudermann T, Lipp P, Laugwitz K-L. Dantrolene rescues arrhythmogenic RYR2 defect in a patient-specific stem cell model of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:180–191. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattman SJ, Witty AD, Gagliardi M, Dubois NC, Niapour M, Hotta A, Ellis J, Keller G. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehat I, Gepstein A, Spira A, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Gepstein L. High-resolution electrophysiological assessment of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: a novel in vitro model for the study of conduction. Circ Res. 2002;91:659–661. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000039084.30342.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehat I, Kenyagin-Karsenti D, Snir M, Segev H, Amit M, Gepstein A, Livne E, Binah O, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Gepstein L. Human embryonic stem cells can differentiate into myocytes with structural and functional properties of cardiomyocytes. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:407–414. doi: 10.1172/JCI12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehat I, Khimovich L, Caspi O, Gepstein A, Shofti R, Arbel G, Huber I, Satin J, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Gepstein L. Electromechanical integration of cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1282–1289. doi: 10.1038/nbt1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keizer J, Smith GD, Ponce-Dawson S, Pearson JE. Saltatory propagation of Ca2+ waves by Ca2+ sparks. Biophys J. 1998;75:595–600. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77550-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JB, Zaehres H, Wu G, Gentile L, Ko K, Sebastiano V, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Ruau D, Han DW, Zenke M, Scholer HR. Pluripotent stem cells induced from adult neural stem cells by reprogramming with two factors. Nature. 2008;454:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature07061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong CW, Akar FG, Li RA. Translational potential of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells for myocardial repair: insights from experimental models. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104:30–38. doi: 10.1160/TH10-03-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujala K, Paavola J, Lahti A, Larsson K, Pekkanen-Mattila M, Viitasalo M, Lahtinen AM, Toivonen L, Kontula K, Swan H, Laine M, Silvennoinen O, Aalto-Setala K. Cell model of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia reveals early and delayed afterdepolarizations. PLoS One. 2012;7:e446600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunst G, Kress KR, Gruen M, Uttenweiler D, Gautel M, Fink RHA. Myosin binding protein C, a phosphorylation-dependent force regulator in muscle that controls the attachment of myosin heads by its interaction with myosin S2. Circ Res. 2000;86:51–58. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian XJ, Hsiao C, Wilson G, Zhu KX, Hazeltine LB, Azarin SM, Raval KK, Zhang JH, Kamp TJ, Palecek SP. Robust cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells via temporal modulation of canonical Wnt signalling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E1848–E1857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200250109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieu DK, Fu J-D, Chiamvimonvat N, Tung KWC, McNerney GP, Huser T, Keller G, Kong C-W, Li RA. Mechanism-based facilitated maturation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;6:191–201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.973420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieu DK, Liu J, Siu CW, McNerney GP, Tse HF, Abu-Khalil A, Huser T, Li RA. Absence of transverse tubules contributes to non-uniform Ca2+ wavefronts in mouse and human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells and Development. 2009;18:1493–1500. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Fu JD, Siu CW, Li RA. Functional sarcoplasmic reticulum for calcium handling of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: Insights for driven maturation. Stem Cells. 2007;25:3038–3044. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Lieu DK, Siu CW, Fu JD, Tse HF, Li RA. Facilitated maturation of Ca2+ handling properties of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes by calsequestrin expression. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 2009;297:C152–C159. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00060.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louch WE, Bito V, Heinzel FR, Macianskiene R, Vanhaecke J, Flameng W, Mubagwa K, Sipido KR. Reduced synchrony of Ca2+ release with loss of T-tubules – a comparison to Ca2+ release in human failing cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;62:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukyanenko V, Gyorke I, Gyorke S. Regulation of calcium release by calcium inside the sarcoplasmic reticulum in ventricular myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1996;432:1047–1054. doi: 10.1007/s004240050233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundy SD, Zhu W-Z, Regnier M, Laflamme MA. Structural and functional maturation of cardiomyocytes derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:1991–2002. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan DH, Kranias EG. Phospholamban: A crucial regulator of cardiac contractility. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:566–577. doi: 10.1038/nrm1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell-line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem-cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): Defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell. 2000;101:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner A, Wernig M, Jaenisch R. Direct reprogramming of genetically unmodified fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1177–1181. doi: 10.1038/nbt1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menasche P, Hagege AA, Vilquin JT, Desnos M, Abergel E, Pouzet B, Bel A, Sarateanu S, Scorsin M, Schwartz K, Bruneval P, Benbunan M, Marolleau JP, Duboc D. Autologous skeletal myoblast transplantation for severe postinfarction left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1078–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami I, Yamada K, Otsuji TG, Yamamoto T, Shen Y, Otsuka S, Kadota S, Morone N, Barve M, Asai Y, Tenkova-Heuser T, Heuser JE, Uesugi M, Aiba K, Nakatsuji N. A small molecule that promotes cardiac differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells under defined, cytokine- and xeno-free conditions. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1448–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JC, Fu JD, Chan YC, Lin DW, Tran H, Tse HF, Li RA. Distinct cardiogenic preferences of two human embryonic stem cell (hESC) lines are imprinted in their proteomes in the pluripotent state. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:553–558. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry CE, Soonpaa MH, Reinecke H, Nakajima H, Nakajima HO, Rubart M, Pasumarthi KBS, Ismail Virag J, Bartelmez SH, Poppa V, Bradford G, Dowell JD, Williams DA, Field LJ. Haematopoietic stem cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiac myocytes in myocardial infarcts. Nature. 2004;428:664–668. doi: 10.1038/nature02446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musunuru K, Domian IJ, Chien KR. Stem cell models of cardiac development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:667–687. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-103948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Okita K, Mochiduki Y, Takizawa N, Yamanaka S. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak A, Barad L, Zeevi-Levin N, Shick R, Shtrichman R, Lorber A, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Binah O. Cardiomyocytes generated from CPVTD307H patients are arrhythmogenic in response to beta-adrenergic stimulation. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16:468–482. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillekamp F, Haustein M, Khalil M, Emmelheinz M, Nazzal R, Adelmann R, Nguemo F, Rubenchyk O, Pfannkuche K, Matzkies M, Reppel M, Bloch W, Brockmeier K, Hescheler J. Contractile properties of early human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes: beta-adrenergic stimulation induces positive chronotropy and lusitropy but not inotropy. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2111–2121. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon E, Kong CW, Li RA. Human pluripotent stem cell-based approaches for myocardial repair: from the electrophysiological perspective. Mol Pharm. 2011;8:1495–1504. doi: 10.1021/mp2002363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Lee MY, Schliffke S, Paavola J, Amos PJ, Ge X, Ye M, Zhu S, Senyei G, Lum L, Ehrlich BE, Qyang Y. Small molecule Wnt inhibitors enhance the efficiency of BMP-4-directed cardiac differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartiani L, Bettiol E, Stillitano F, Mugelli A, Cerbai E, Jaconi ME. Developmental changes in cardiomyocytes differentiated from human embryonic stem cells: a molecular and electrophysiological approach. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1136–1144. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satin J, Itzhaki I, Rapoport S, Schroder EA, Izu L, Arbel G, Beyar R, Balke CW, Schiller J, Gepstein L. Calcium handling in human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1961–1972. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer H, Theben T, Hescheler JR, Lindner M, Brandt MC, Wartenberg M. Characteristics of calcium sparks in cardiomyocytes derived from embryonic stem cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H411–H421. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedan O, Dolnikov K, Zeevi-Levin N, Leibovich N, Amit M, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Binah O. 1,4,5-Inositol trisphosphate-operated intracellular Ca2+ stores and angiotensin-II/endothelin-1 signaling pathway are functional in human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells. 2008;26:3130–3138. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon TR, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. Potentiation of fractional sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release by total and free intra-sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium concentration. Biophys J. 2000;78:334–343. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba Y, Fernandes S, Zhu W-Z, Filice D, Muskheli V, Kim J, Palpant NJ, Gantz J, Moyes KW, Reinecke H, Van Biber B, Dardas T, Mignone JL, Izawa A, Hanna R, Viswanathan M, Gold JD, Kotlikoff MI, Sarvazyan N, Kay MW, Murry CE, Laflamme MA. Human ES-cell-derived cardiomyocytes electrically couple and suppress arrhythmias in injured hearts. Nature. 2012;489:322–325. doi: 10.1038/nature11317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sil AK, Maeda S, Sano Y, Roop DR, Karin M. IκB kinase-α acts in the epidermis to control skeletal and craniofacial morphogenesis. Nature. 2004;428:660–664. doi: 10.1038/nature02421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits PC, van Geuns RJ, Poldermans D, Bountioukos M, Onderwater EE, Lee CH, Maat AP, Serruys PW. Catheter-based intramyocardial injection of autologous skeletal myoblasts as a primary treatment of ischemic heart failure: clinical experience with six-month follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:2063–2069. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song LS, Guatimosim S, Gomez-Viquez L, Sobie EA, Ziman A, Hartmann H, Lederer WJ. Calcium biology of the transverse tubules in heart. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1047:99–111. doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulakhe PV, Vo XT. Regulation of phospholamban and troponin-I phosphorylation in the intact rat cardiomyocytes by adrenergic and cholinergic roles of cyclic-nucleotides, calcium, protein-kinases and phosphatases and depolarization. Mol Cell Biochem. 1995;149:103–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01076569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun N, Yazawa M, Liu J, Han L, Sanchez-Freire V, Abilez OJ, Navarrete EG, Hu S, Wang L, Lee A, Pavlovic A, Lin S, Chen R, Hajjar RJ, Snyder MP, Dolmetsch RE, Butte MJ, Ashley EA, Longaker MT, Robbins RC, Wu JC. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:130ra147–130ra147. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull IC, Karakikes I, Serrao GW, Backeris P, Lee J-J, Xie C, Senyei G, Li RA, Akar FG, Hajjar RJ, Hulot J-S, Costa KD. Human engineered cardiac tissues from embryonic stem cell derived cardiomyocytes show advanced structure and function. FASEB J. 2013 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Chen A, Lieu DK, Karakikes I, Chen G, Keung W, Chan CW, Hajjar RJ, Costa KD, Khine M, Li RA. Effect of engineered anisotropy on the susceptibility of human pluripotent stem cell-derived ventricular cardiomyocytes to arrhythmias. Biomaterials. 2013;34:8878–8886. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren L, Manos PD, Ahfeldt T, Loh YH, Li H, Lau F, Ebina W, Mandal PK, Smith ZD, Meissner A, Daley GQ, Brack AS, Collins JJ, Cowan C, Schlaeger TM, Rossi DJ. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:618–630. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu CH, Police S, Rao N, Carpenter MK. Characterization and enrichment of cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells. Circ Res. 2002;91:501–508. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000035254.80718.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue T, Cho HC, Akar FG, Tsang SY, Jones SP, Marban E, Tomaselli GF, Li RA. Functional integration of electrically active cardiac derivatives from genetically engineered human embryonic stem cells with quiescent recipient ventricular cardiomyocytes – Insights into the development of cell-based pacemakers. Circulation. 2005;111:11–20. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151313.18547.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Soonpaa MH, Adler ED, Roepke TK, Kattman SJ, Kennedy M, Henckaerts E, Bonham K, Abbott GW, Linden RM, Field LJ, Keller GM. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR plus embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–526. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Klos M, Wilson GF, Herman AM, Lian X, Raval KK, Barron MR, Hou L, Soerens AG, Yu J, Palecek SP, Lyons GE, Thomson JA, Herron TJ, Jalife J, Kamp TJ. Extracellular matrix promotes highly efficient cardiac differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells the matrix sandwich method. Circ Res. 2012;111:1125–1178. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.273144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Kelley J, Schmeisser G, Kobayashi YM, Jones LR. Complex formation between junction, triadin, calsequestrin, and the ryanodine receptor – Proteins of the cardiac junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum membrane. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23389–23397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZY, Zhou B, Xie LP. Modulation of protein kinase signalling by protein phosphatases and inhibitors. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;93:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T, Zhang ZN, Rong Z, Xu Y. Immunogenicity of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;474:212–215. doi: 10.1038/nature10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XL, Gutierrez LM, Chang CF, Hosey MM. The α1-subunit of skeletal-muscle L-type Ca channels is the key target for regulation by A-kinase and protein phosphatase-1C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;198:166–173. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu WZ, Santana LF, Laflamme MA. Local control of excitation-contraction coupling in human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu WZ, Xie Y, Moyes KW, Gold JD, Askari B, Laflamme MA. Neuregulin/ErbB signalling regulates cardiac subtype specification in differentiating human embryonic stem cells. Circ Res. 2010;107:776–786. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]