Abstract

Archaea contain, both a functional proteasome and an ubiquitin-like protein conjugation system (termed sampylation) that is related to the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) of eukaryotes. Archaeal proteasomes have served as excellent models for understanding how proteins are degraded by the central energy-dependent proteolytic machine of eukaryotes, the 26S proteasome. While sampylation has only recently been discovered, it is thought to be linked to proteasome-mediated degradation in archaea. Unlike eukaryotes, sampylation only requires an E1 enzyme homolog of the E1-E2-E3 ubiquitylation cascade to mediate protein conjugation. Furthermore, recent evidence suggests that archaeal and eurkaryotic E1 enzyme homologs can serve dual roles in mediating protein conjugation and activating sulfur for incorporation into biomolecules. The focus of this book chapter is the energy-dependent proteasome and sampylation systems of Archaea.

Introduction

Archaea are one of three major lineages of life which share deep evolutionary roots with eukaryotes. Although typically single-celled, many Archaea thrive in conditions once thought to be uninhabitable to life such as temperatures above 100°C, saturating salt and extreme pH. Thus, Archaea provide an exciting opportunity to examine how proteolytic systems can function in maintaining the quality of proteomes when cells are growing at physical conditions considered suboptimal for protein folding and stability.

Although the hydrolysis of peptide bonds is exergonic (releasing energy), many proteolytic machines (e.g. the proteasome) require energy for protein degradation. Of the various types of proteases, it is often the energy-dependent proteases that are important in regulating central processes of the cell such as protein quality, cell division and survival after exposure to stress [1, 2]. The energy-dependence of the proteolytic system adds assurance that the appropriate protein substrate has been selected prior to its destruction, which would otherwise come at a high energy cost.

Energy-dependent proteases (e.g. Lon, Clp, FtsH, HslUV and the proteasome), while not necessarily conserved in primary amino acid sequence, share a common protein architecture of self-compartmentalization [3]. In general, the proteolytic active-sites of the protease are sequestered within a chamber that has narrow openings for substrate entry. These openings are often gated to reduce the non-specific entry of proteins into the chamber [4–7]. Typically, the chamber alone does not degrade folded proteins but requires association with regulatory ATPases (either a protein domain or separate protein complex). The ATPases couple the hydrolysis of ATP to the unfolding and the translocation of the substrate protein, so that the substrate protein can access the proteolytic active sites lining the central chamber of the protease.

The ATPase regulators of energy-dependent proteolysis belong to the AAA + (ATPases associated with a variety of cellular activities) superfamily [8, 9]. These AAA + proteins form hexameric rings that associate with a compartmentalized cylindrical peptidase. In some cases, the peptidase forms a hexameric ring (e.g. HslV), while in other cases the peptidase exhibits a seven-fold symmetry. Hence, symmetry mismatch can exist between the ATPase and protease components. For example, the hexameric ATPases (ClpA, ClpC and ClpX) associate with ClpP (which is composed of two heptameric rings). Similarly, the proteasomal ATPases (ARC/Mpa of actinobacteria, PAN of Archaea, and Rpt1-6 of eukaryotes) all form hexamers and interact with a 20S core particle (CP), which has seven-fold symmetry. Energy-dependent proteases such as Lon and FtsH differ from most AAA + proteases, in that both the ATPase and proteolytic domains are located on the same polypeptide chain [10] (see also accompanying reviews [11, 12]).

Archaeal Proteasomes

Similarly to eukaryotes, all Archaea are predicted to use proteasomes as one of their major systems for energy-dependent proteolysis [13]. All species of Archaea with sequenced genomes are predicted to encode a 20S CP of α- and β-type subunit composition as well as an AAA + regulator (PAN and/or Cdc48) thought to associate with the CP and mediate protein degradation [13, 14]. Archaea also contain the membrane bound B-type Lon protease [15, 16]. However in contrast to bacteria, Archaea lack homologs of the membrane-spanning FtsH protease and, in most cases also lack HslUV, Clp and the A-type Lon proteases [15, 16]. Like other bacteria, the actinobacteria (including species from Mycobacterium, Rhodococcus and Frankia) encode many energy-dependent proteases including the proteasomal CPs and its associated AAA + components termed ARC or Mpa, in addition to Lon, Clp and FtsH proteases, but do not encode the HslUV protease [17–20]. Overall, the distribution of energy-dependent proteases in Archaea is more like eukaryotes than either bacteria or bacterial-like organelles of eukaryotes.

Proteasomal Core Particles (CPs)

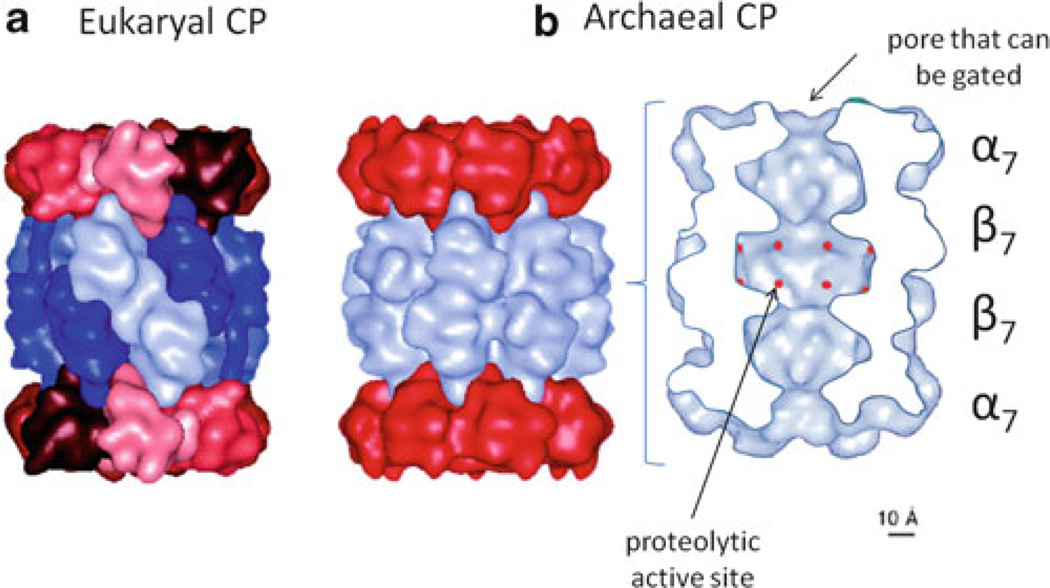

Proteasomes are composed of a 20S CP that is required for the hydrolysis of unfolded proteins and small peptides [21]. The CP is formed from structurally related α- and β-type subunits that are arranged into four-stacked heptameric rings (Fig. 11.1). The two outer rings are composed of α-subunits, and the two inner rings are of β-subunits. These subunits are arranged to form a cylindrical particle with openings on both ends of the particle, gated by the N-termini of the α-subunits. The gates open into a central channel that connects three interior chambers (two antechambers and one central chamber). The central chamber is lined with the proteolytic active sites that are formed by the N-terminal threonine residues of the β-subunits and are exposed after cleavage of the β propeptide during CP assembly. In contrast to eukaryotic CPs, which are formed from seven different α-subunits (α1 to α7) and seven different β-subunits (β1 to β7) that assemble into a 28-subunit complex of dyad symmetry. Core particles from Archaea and actinobacteria are typically assembled from one to two different α-subunits and one to two different β-subunits.

Fig. 11.1. 20S proteasome core particles (CPs).

CPs are composed of four stacked heptameric rings of α- and β-type subunits (indicated by α7 and β7, respectively) that form a cylindrical structure. The central channel of the CP is accessed by gated pores on each end of the cylinder and connects three interior chambers. Proteolytic active sites formed by β-type subunits (indicated in red) line the central chamber that is flanked by two antechambers. CPs of (a) the eukaryote Saccharomyces cerevisiae and (b) the archaeon Thermoplasma acidophilum are presented as examples. (Figure modified from [22, 23] with permission)

Proteolytic Active Sites of Proteasomes

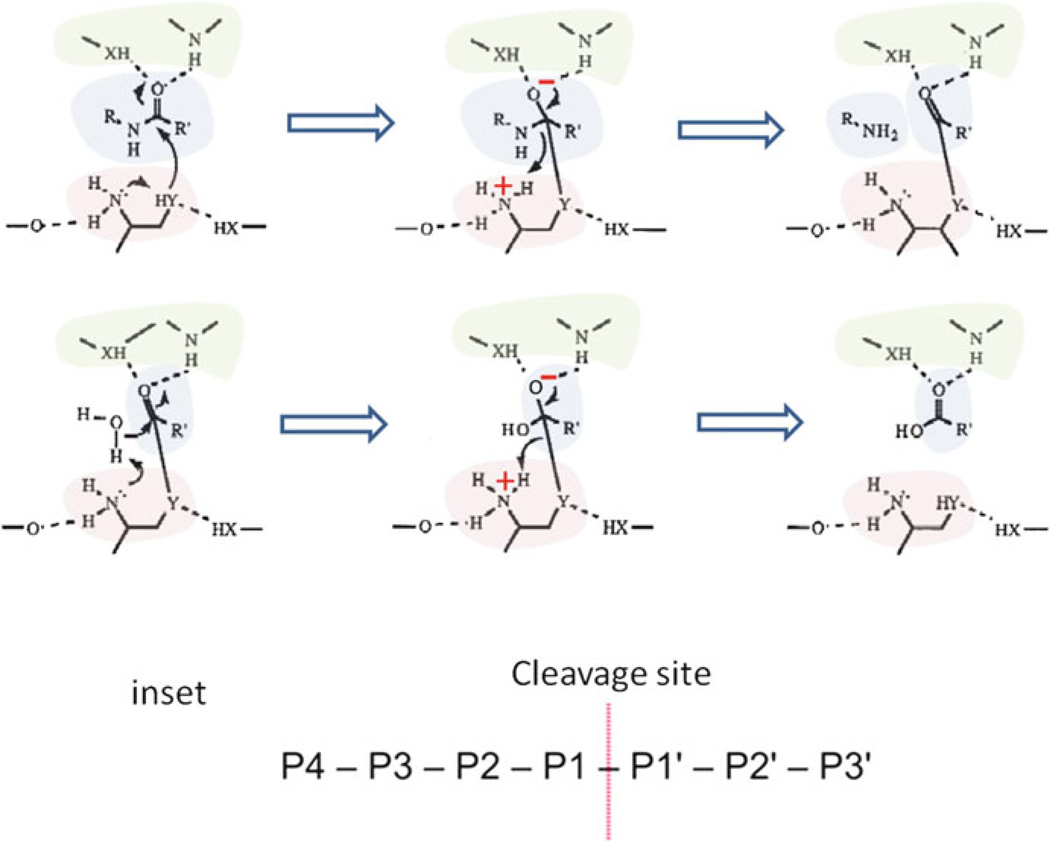

The proteolytic active sites of proteasomes, sequestered within the CP, are of the N-terminal nucleophile (Ntn) hydrolase superfamily [24–26]. This superfamily includes penicillin acylases, aspartylglucosaminidases and other hydrolytic enzymes. While Ntn hydrolases are not necessarily conserved in primary sequence, these enzymes hydrolyze amide bonds and undergo autocatalytic post-translational processing to expose an N-terminal residue (Thr, Ser or Cys) that is used as nucleophile (the side chain OH or SH group) and proton donor (the Nα-amino group) in a structurally related active site con figuration. The Ntn hydrolase reaction is initiated when the Ntn residue donates the proton of its side chain to its own α-amino group for attack of the carbonyl carbon of the substrate (Fig. 11.2). A negatively charged tetrahedral intermediate is formed that is stabilized by hydrogen bonding to the oxyanion hole. The Ntn α-amino group completes the acylation step by donating a proton to the nitrogen of the substrate bond undergoing hydrolysis. While part of the cleaved substrate (the portion with the R or P1 group) is released, a covalent bond is formed between the nucleophile of the Ntn and the remaining substrate (with the R' or P1' group) that must be deacylated for product release. Deacylation is initiated when the hydroxyl group of water attacks the carbonyl carbon of the covalent acyl-enzyme intermediate. The Ntn α-amino group accepts a proton from water and stabilizes the negatively charged enzyme intermediate. Reprotonation of the nucleophile by the Ntn α-amino group completes this reaction.

Fig. 11.2. Mechanism of proteasomes and other related Ntn-hydrolyases in the hydrolysis of an amide bond.

Substrate, shaded in blue; Ntn active site residue, shaded in red; oxyanion hole, shaded in green; charged state, indicated by + or − in red font; Y, oxygen or sulfur; X, nitrogen or oxygen; R-R', substrate bond cleaved (comparable to the P1–P1' peptide bond cleaved by proteases as depicted in the inset) (Figure modified from [26] with permission)

While the mechanism of peptide hydrolysis by the CP active site resembles serine proteases, only one amino acid (Thr1) serves as the catalytic center, rather than the three amino acids (Asp–His–Ser) that constitute the catalytic triad of serine proteases [27]. Both the nucleophile (hydroxyl side chain) and the base (α-amino group) of the CP proteolytic reaction exist in the same amino acid (Thr). Like β-lactamase and some esterases, there is no acid component in the CP active site [28]. Serine can substitute for threonine as the Ntn active site in CPs (T1S variants) for the hydrolysis of peptide amide substrates such as N-succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amido-4-methyl coumarin (Suc-LLVY-amc). However, CP T1S variants are severely impaired in their ability to cleave longer peptides, revealing the importance of the threonine side chain methyl group in active site conformation [29, 30].

Cleavage of N-Terminal Propeptide to Expose Proteolytic Active Site

Proteasomal active sites are formed through intramolecular autolysis of β-type precursor proteins during CP assembly [31]. The CP β-subunits are typically translated as precursor proteins with N-terminal propeptides that are removed during formation of the CP. The β-subunits remain monomeric, unprocessed and inactive until assembled with α-subunits into the CP. In most cases, the propeptide of the β-subunit is autocatalytically removed at a conserved G↓T motif (where ↓ represents the site of peptide bond cleavage) to generate a mature β-subunit that contains an active N-terminal threonine. However, some β-subunits that assemble into CPs are not cleaved at conserved G↓T motifs [32, 33]. For example, the eukaryotic β7 and β6 precursors are cleaved at N↓T and H↓Q sites, respectively, resulting in the removal of N-terminal propeptides and formation of inactive β subunits in CPs. Likewise, the eukaryotic β3 and β4 subunits are not cleaved but are assembled into CPs as inactive subunits.

The position and residues surrounding the cleavage site of the propeptide of proteasomal β-subunits is predicted to be highly diverse among archaea. Like eukaryotes and actinobacteria, Archaea are known to synthesize β-type precursor proteins that are cleaved at G↓T motifs resulting in the removal of N-terminal propeptides of variable length (6–49 residues) and the formation of mature β-subunits with active CPs. This knowledge is based on N-terminal sequencing of CP subunits purified from Archaea of the phylum Euryarchaeota (i.e., Thermoplasma acidophilum, Methanosarcina thermophila, Haloferax volcanii and Pyrococcus furiosus) [34–37]. Similarly, most archaea are predicted to encode at least one β-type precursor protein that is cleaved at a G↓T motif to release an N-terminal propeptide and generate an active β-type subunit. Interestingly, select Crenarchaeota (i.e., Thermoproteus and Pyrobaculum species) and Candidatus Caldiarchaeum subterraneum of the novel division Aigarchaeota have β-subunit homologs devoid of propeptides (only an initiator methionine residue, which may be removed by a methionine aminopeptidase, is predicted to precede the conserved active site threonine residue). Furthermore, most Crenarchaeota are predicted to encode two different β-type proteins with at least one of these proteins harbouring an N-terminal extension that lacks the classical G↓T cleavage site. Whether or not these latter β-subunits associate in CPs and form active sites remains to be determined.

The propeptides of β-type precursors (‘β-propeptides’) can modulate the function and assembly of proteasomal CPs. The β-propeptides of yeast protect the N-terminal threonine active sites of the β-subunits from Nα-acetylation and promote CP assembly [38]. In actinobacteria, the β-propeptide of Rhodococcus erythropolis is important for the formation of CPs, while the β-propeptide of Mycobacterium tuberculosis mediates temperature-dependent inhibition of CP assembly [41, 42]. By contrast to the actinobacteria and yeast, the β-propeptides of archaea appear to be dispensable for CP assembly. Archaeal β-subunits can be produced in recombinant E. coli without an N-terminal propeptide (βΔpro) and then reconstituted with α-type subunits in vitro to form active CPs (i.e., Methanocaldococcus jannaschii CPs) [43]. Likewise, archaeal CPs can form active complexes when βΔpro variants are co-expressed with α-type subunits in recombinant E. coli (i.e., T. acidophilum and M. thermophila CPs) [30, 31]. By modulating the ionic strength of the buffer, haloarchaeal CPs (of H. volcanii) can also be disassembled into monomers and reconstituted into active CPs (based on gel filtration and activity assays) [37].

While archaeal β-propeptides are not required for the generation of active CPs in vitro or when produced in E. coli, β-propeptides are likely to be important in the proper formation of proteasomes within archaeal cells. In support of a function for β-propeptides in Archaea, genetic deletion of the 49-residue propeptide of the H. volcanii β-subunit results in undetectable levels of this protein (βΔpro) (either by immunoblot or His-tag purification) when expressed in its native host H. volcanii (Kaczowka and Maupin-Furlow, unpublished). In contrast, H. volcanii βΔpro is readily detected and purified (using a His-tag) when expressed in a heterologous host, E. coli [44]. Likewise, the β-subunit is synthesized and purified at high levels when the β-propeptide is added to the H. volcanii expression system [44]. Whether or not these findings are unique to H. volcanii remains to be determined.

Notably, the N-terminal propeptides (typically over 30 residues) of the β-subunits of haloarchaea are predicted to be the longest amongst all Archaea. Haloarchaea are unusual in that they maintain osmotic balance with hypersaline environments by accumulating molar concentrations of KCl in their cytoplasm [45]. In order to cope with these harsh conditions, haloarchaea synthesize proteins with a high negative surface charge, which makes their proteins more soluble and flexible at high concentrations of salt compared to non-halophilic proteins [46]. Thus, the extended N-terminal propeptide of β-subunits may be needed to facilitate folding and assembly of the CP in the ‘harsh’ cytosolic environment found in haloarchaeal cells. Alternatively, given that Nα-acetylation is quite common in haloarchaea [47–49], the N-terminal propeptide of β-subunits may prevent Nα-acetylation of the active site threonine residue as has been observed in yeast.

CP Active Site Number and Subunit Complexity

While all proteasomes to date have 14 α-type and 14 β-type subunits assembled into each CP, the ratio of β-type subunits with N-terminal threonine active site residues per CP varies among the three domains of life. These differences in active site number do not appear to influence the overall size of peptide products generated nor the rate of peptide bond hydrolysis, based on comparison of archaeal and eukaryotic proteasomes [50, 51].

In general, proteasomal CPs from eukaryotes have less proteolytic active sites per particle than CPs from either archaea or actinobacteria. Eukaryotic CP subtypes have six active sites per particle formed by three of the seven different β-type subunits per heptameric β-ring [52]. For example, within the housekeeping CP of eukaryotes only the β1, β2 and β5 subunits are proteolytically-active (the β3, β4, β6 and β7 subunits are inactive). In response to cytokines and microbial infections, β1, β2 and β5 are replaced by β1i, β2i and β5i, which are also active and alter CPs to generate peptide products optimized for MHC class I loading in hematopoietic cells [53].

In contrast to eukaryotes, all archaeal (and actinobacterial) CPs purified to date have 14 active sites per particle and are typically purified as a cylindrical ~600–700 kDa complex of a single type of β subunit that associates with a single type of α subunit (Fig. 11.1). Thus, most archaeal CPs have identical proteolytic active sites with some determined by N-terminal sequencing of the β-subunits [34, 36, 37, 54]. Examples of CPs purified from Archaea (or recombinant E. coli expressing these archaeal genes) composed of only a single type of α- and β-subunits, include CPs from Thermoplasma acidophilum [55], Thermoplasma volcanium [56], Methanosarcina thermophila TM-1 [30, 36], Methanosarcina mazei [57], Methanocaldococcus jannaschii [43], and Archaeoglobus fulgidus [58].

Although Archaea with CPs composed of only a single type of α- and β-subunit have received most attention, as simplified models for biochemistry, the majority of Archaea are predicted to encode multiple α- and/or β-subunit homologs based on genome sequence. Most Crenarchaeota encode single α-type and two different β-type subunit homologs, while Thaumarchaeota, Korarchaeota and select families of Euryarchaeota (Halobacteriaceae and Thermococcaceae) commonly encode multiple α-type and/or β-type subunit homologs. Interestingly, the recently described Candidatus Caldiarchaeum subterraneum is predicted to encode three different β-subunits and a single α-subunit. Many of the Archaea with two or more coding sequences for β-subunits harbour one gene that encodes a β-subunit devoid of the classical G↓T cleavage motif, suggesting that the protein is synthesized either as an inactive β-subunit or has a propeptide cleavage site that differs from the CPs characterized from Euryarchaeota and eukaryotes.

Archaeal CPs composed of a single type of α subunit and two different β-type subunits (both containing a G↓TTT cleavage motif) have been characterized at the biochemical level. Initially, CPs of only a single α/β composition were purified from the archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus [34]. However, DNA sequencing of the complete genome of this hyperthermophile predicted that two β-type subunits (β1 and β2) and a single α-type subunit [59] existed in this species. Further analysis by microarray revealed that the level of the β1 transcripts were upregulated after cells were exposed to heat shock, which might explain why only one β-type protein was detected in CPs purified from P. furiosus grown under normal (non-stressed) conditions [60]. To examine the function of CPs which contain multiple β-type proteins, the α-type and both β-type proteins were produced in E. coli and reconstituted at different temperatures in vitro [60]. Using this approach, an increased ratio of β1 to β2 was observed in CPs assembled at higher temperatures, which correlated with more thermostable properties. Surprisingly, the α and β1 proteins could not be reconstituted into CPs or form particles with peptide hydrolyzing activity independent of β2. Based on these results, the P. furiosus β1 is thought to stabilize α2/β CPs at high temperature and to influence the biocatalytic properties of the proteasome.

CP subtypes, of different α- and β-type subunit composition, have also been directly purified from an archaeon. The haloarchaeon H. volcanii encodes a single β-type and two α-type (α1 and α2) CP subunits [37]. Not surprisingly, the β-type gene is essential for growth and the presence of one of the two α-type genes is required for growth (based on conditional mutation) [61]. All three of the different CPs (α1 β, α2β and α1α2β) have been purified from H. volcanii [37, 44, 62]. Each of these different CP subtypes are active in the hydrolysis of peptides and unfolded proteins with the α1α2β-proteasome apparently asymmetric based on the detection of homooligomeric rings of α1 and α2 [44, 62]. The population of CP subtypes is likely altered during growth based on the finding that levels of α2 increase several-fold as cells transition to stationary phase, while α1 levels remain relatively constant [63]. Although it remains to be established, differences in α-type subunit composition are thought to influence the type of regulator that associates with the CPs in H. volcanii. Interestingly, in H. volcanii the CPs (and PAN ATPases) are also modified post-/co-translationally (phosphorylation, Nα-acetylation and methylation) suggesting an additional layer of regulation in modulating the populations of proteasomes in archaeal cells [64–66].

Proteasomal Regulators

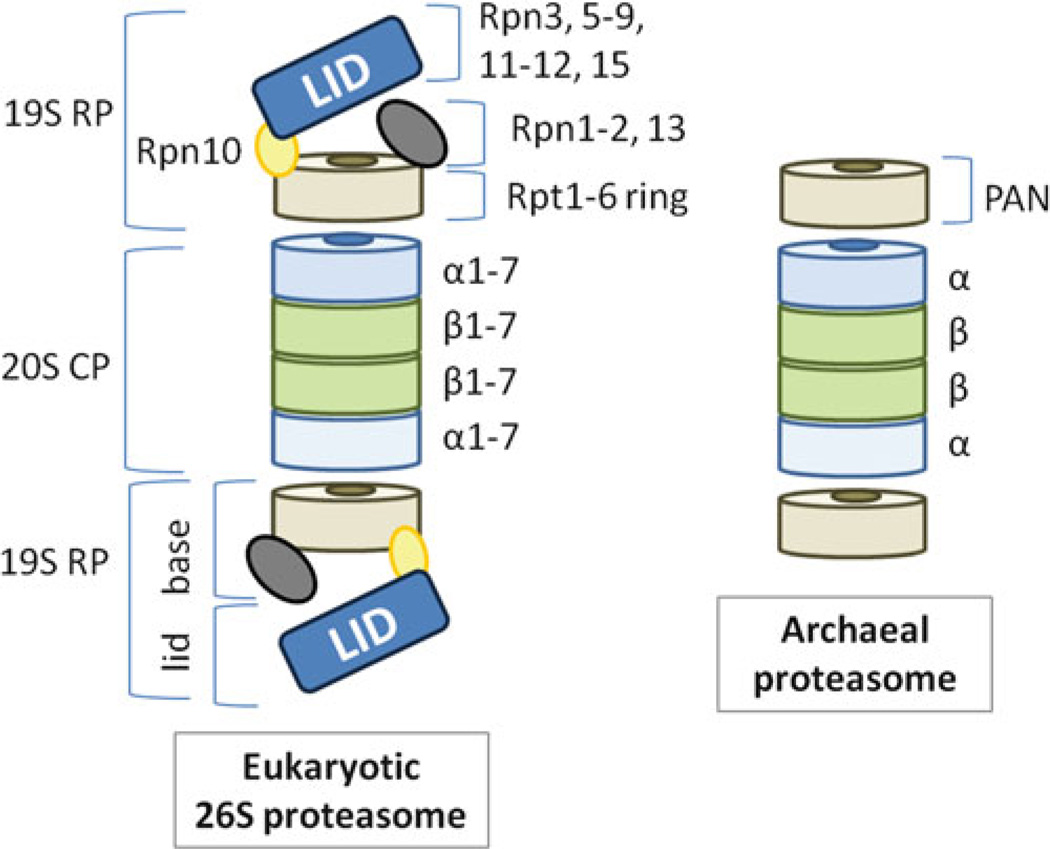

Eukaryotic proteasomal CPs co-purify with a variety of accessory proteins including ATPase regulators, such as the 19S regulatory particle (RP), and non-ATPase regulators such as Blm10/PA200 and the 11S regulators PA28, PA26 and REG [67]. Of these regulators, the 19S RP can associate with either end of the CP cylinder to form the 26S proteasome that catalyzes the ATP-dependent degradation of proteins (Fig. 11.3) [22]. Subunits of the RP are grouped into two major categories including the RP non-ATPase subunits (Rpn) and the RP AAA + (triple-A+) subunits (Rpt) of the ATPases associated with various cellular activities (AAA) family within the AAA + superfamily [68]. In yeast, RPs are dissociated into base and lid subcomplexes by deletion of the gene encoding the Rpn10 subunit [69] (Fig. 11.3). The base subcomplex is composed of Rpn1-2, Rpn13 and six different Rpt subunits (Rpt1-6) that form a hexameric ring in direct contact with the outer rings of the CP complex [69].

Fig. 11.3. ATP-dependent proteasomes of eukaryotes compared to archaea.

Proteasomal CPs can associate on each end of their cylindrical structure with heptameric rings of AAA + proteins including eukaryotic Rpt1-6 and archaeal PAN. Rpt1-6 are AAA + subunits of the 19S regulatory particle (RP) that associates with CPs to form 26S proteasomes. In yeast, the 19S RP can be dissociated into lid and base subcomplexes by deletion of the RPN10 gene. PAN is an AAA ATPase that forms a hexameric ring and associates with CPs in vitro. PAN is common to many but not all archaea

While archaeal CPs have yet to be purified in complex with regulatory proteins from its native host, archaeal CPs can associate with ATPase regulators in vitro (Fig. 11.3). Studies of this association were initiated after release of the first archaeal genome sequence (M. jannaschii), which was predicted to encode a close homolog of the Rpt1-6 subunits of eukaryotic 26S proteasomes [70]. The archaeal Rpt homolog (termed PAN for its role as a proteasome-activating nucleotidase) was synthesized and purified from recombinant E. coli and shown to be required for the degradation of substrate proteins (e.g., casein) by CPs including those of T. acidophilum [71] and M. jannaschii [43]. M. jannaschii (Mj) PAN forms a relatively simple homohexameric ATPase complex and, thus, has served as an ideal model to understand how Rpt-like proteins function in the degradation of proteins by proteasomes (see later). While all Archaea encode proteasomal CPs based on genome sequence, many do not encode Rpt/PAN homologs including archaea of the Thaumarchaeota, Korarchaeota, Thermoplasmata class of Euryarchaeota, Aigarchaeota (Candidatus Caldiarchaeum subterraneum), and Thermoproteales order of Crenarchaeota. Whether or not ATPases beyond PAN can regulate these archaeal CPs remains to be determined. Members of the Cdc48/VCP/p97 subfamily of AAA + proteins are universally distributed among archaea, and, in eukaryotes, these Cdc48-type proteins are associated with the ubiquitin-proteasome system in endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (ERAD) [72, 73]. The T. acidophilum VCP is an archaeal Cdc48-type ATPase that has been purified and shown to function as an ATP-dependent unfoldase and stimulate protein degradation using mutant CPs with open gates [74] (see below). More recently, VCP has been shown to associate with CPs and stimulate peptide and protein degradation [75]. Thus, archaeal CPs appear to be regulated by multiple types of AAA + proteins.

Gated Openings of Proteasomal Core Particles (CPs)

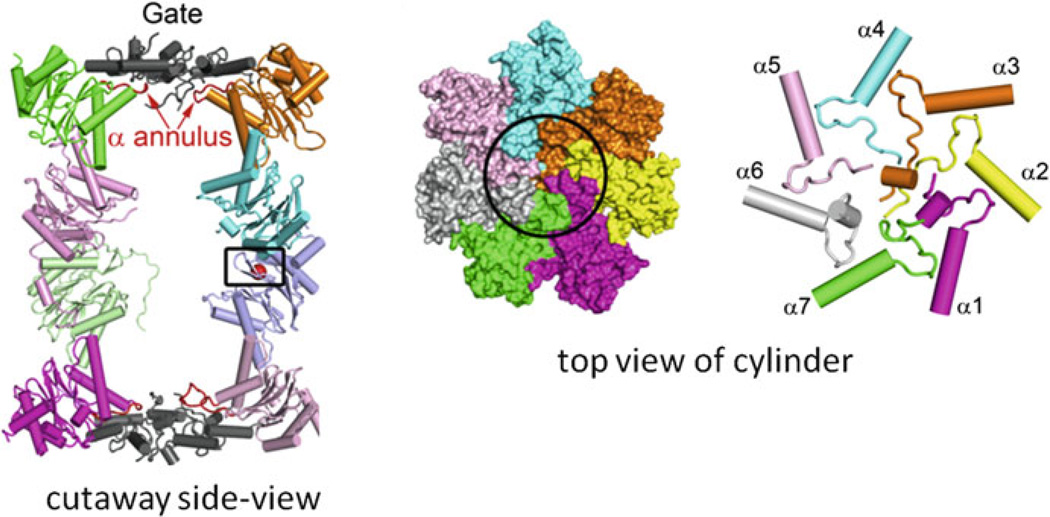

The proteolytic active sites of proteasomes are sequestered within the interior of the chambered CP, which has gated openings to control substrate entry. The first 3-D structure of the proteasome, which provided insight into its compartmentalization, came from the CP of the archaeon T. acidiophilum (TaCP) that was produced in E. coli [75, 76]. The TaCP structure revealed narrow (13 Å) openings on each end of the cylindrical particle (113 Å diameter by 148 Å length) that connected a central channel leading to an interior chamber lined with proteolytic active sites. Subsequent, X-ray structures of yeast and bovine CPs revealed particles with no apparent openings on the ends for substrates to access the proteolytic active sites or for products to exit the chambered particle [77, 78]. The N-terminal tails of α-type subunits within the eukaryotic CP structures appeared to block the channel openings and, thus, were thought to gate substrate entry (Fig. 11.4).

Fig. 11.4. Eukaryal proteasomal CPs are gated.

In X-ray crystal structures of eukaryotic (e.g., yeast and bovine) CPs, the central channel used for protein substrate entry is gated by the N-terminal tails of α-type subunits (Figure modified from [67] with permission)

With the yeast CP as a model, genetic modifications to residues associated with the gate and structural analysis of CPs associated with regulators thought to open the gate provided evidence for a gating mechanism in eukaryotes. In particular, genetic deletion of the N-terminal tail of the yeast α3 (α3ΔN) was found to open the channel and derepress the peptide hydrolysis mediated by CPs [79]. The α3ΔN mutation also increased the size of CP-generated peptide products suggesting CP gating controls product release in addition to substrate entry [80]. Binding of regulators to CPs in vivo, was thought to relieve the inhibition mediated by the α-subunit tails and open the CP gates [79]. Indeed, deletion of the gate (N-terminal tail of α3) in mutant proteasomes containing an active site mutation in the ATPase subunit (Rpt2) was sufficient to overcome defects in peptide hydrolysis [80]. Likewise, crystal structures of yeast CPs in complex with the non-ATPase activator PA26 revealed, that loops in PA26 could induce conformational changes in the α-subunit tails to open the gate, separating the CP interior from the intracellular environment [81].

Although gated openings were not evident in the early archaeal CP crystal structures (most likely due to the disordered structure of the α subunit N-terminal tail) [58, 76], several lines of evidence now support a gating mechanism for archaeal CPs. For example, deletion of the N-terminal tail of the T. acidophilum α-subunit (αΔN) reduces the central mass of heptameric rings formed by the α-subunit in electron micrographs, supporting the localization of these tails near the central channel of mature CPs [82]. Increased rates of unfolded protein hydrolysis are also observed for TaCPs containing αΔN-subunits compared to wild-type suggesting that deletion of the N-terminal residues of the α-subunit generates a “gateless” CP [82, 83]. The recent crystal structure of a CP assembled from M. jannaschii α- and β-subunits produced in E. coli also provides evidence that an archaeal CP can be stabilized in closed gate conformation [84]. Furthermore, addition of specific peptides (based on the C-terminal tail of MjPAN) causes a conformational change in TaCPs that is consistent with gate opening (Fig. 11.5) (see later) [85, 86]. Interestingly, the N-terminal tails of the α-subunits that form the gates can be highly dynamic and extend inside and outside the CP cylinder, based on methyl-transverse relaxation optimized nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy experiments of TaCPs [87].

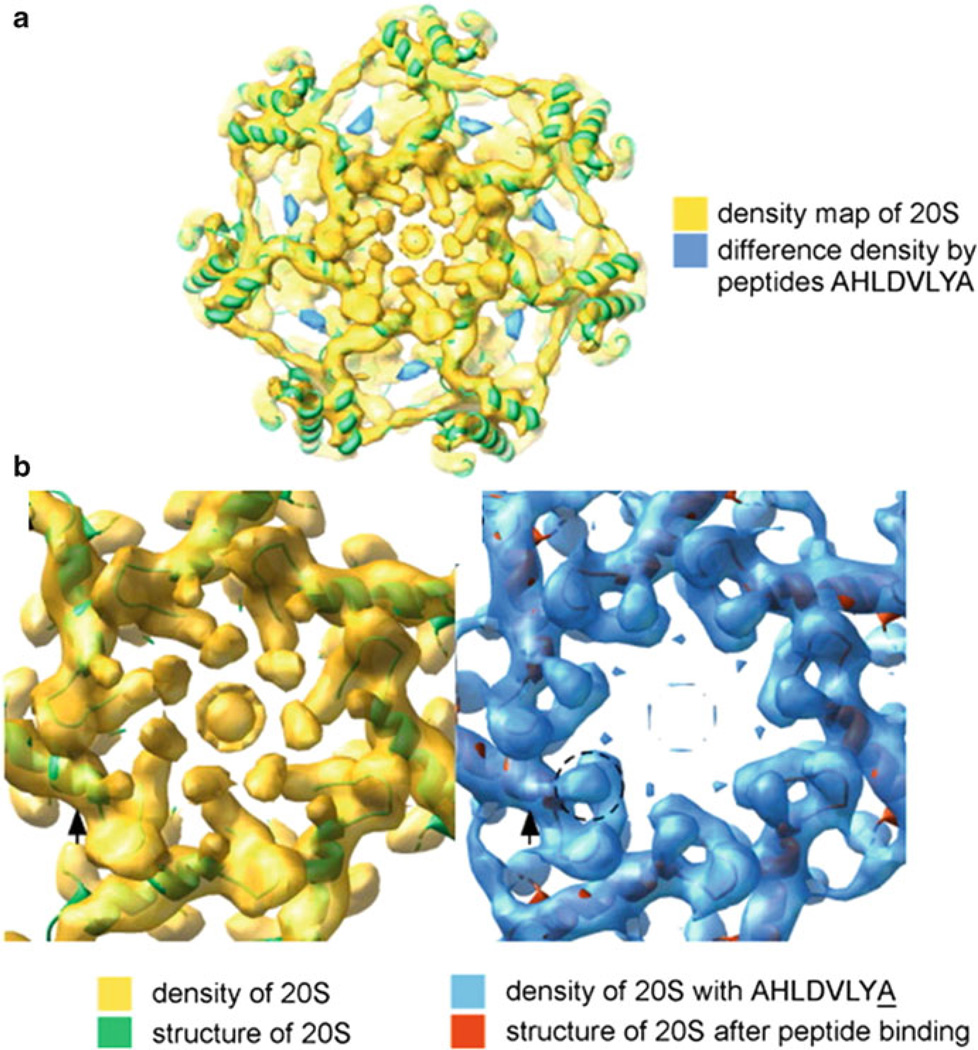

Fig. 11.5. Archaeal proteasomal CPs are gated.

Cryo-electron microscopy reveals: (a) sites within the intersubunit pockets of α subunits in the TaCP that are bound by peptides mimicking the C-terminal tail of MjPAN and (b) structures of the TaCP gate in the closed and open forms induced by these peptides (Figure modified from [85] with permission)

Functional Association of Proteasomal ATPases and CPs

While proteasomal CPs have yet to be purified in association with defined regulatory proteins from archaeal cells, MjPAN (an archaeal Rpt homolog) can be reconstituted with CPs in vitro. Formation of MjPAN:TaCP complexes has been detected by immunoprecipitation, electron microscopy and surface plasmon resonance. These complexes form when recombinant MjPAN and TaCP are incubated in the presence of ATP or a non-hydrolyzable ATP analogue (AMPPNP or ATPγS), but not when incubated with ADP or in the absence of nucleotide [83]. Thus, ATP binding is required for MjPAN:TaCP association. In electron micrographs of negatively stained complexes, MjPAN is associated as a two-ringed structure that caps either one or both ends of the TaCP [83]. The outer ring of MjPAN (distal to the TaCP) is thought to correspond to the N-terminal domain of the protein based on analogy to a related AAA + complex from bacteria, HslU [88–90]. The C-terminal domain of MjPAN is important for docking with CPs and opening the CP gates (see below).

Docking of the Proteasomal ATPase (PAN) to the CP

Proteasomal ATPases such as MjPAN have a C-terminal tail that is essential for docking with CPs and opening the CP gates. A series of elegant studies focused on the association of the archaeal MjPAN with CPs facilitated this discovery [85, 86, 91]. These studies on MjPAN were guided by similarities to the bacterial HslUV protease and eukaryotic non-ATPase 11S regulators (PA28 and PA26) in association with proteasomal CPs. While somewhat controversial at the time, the C-terminal domain of HslU (the AAA + component of the HslUV protease) was thought to be required for association with HslV [90, 92]. Likewise, the extreme C-terminus of the 11S regulator PA28 was known to be required for association with CP [93], and structural analysis revealed that the C-terminal tail of PA26 (a related 11S regulator) docked into pockets of the CP, formed by adjacent α-subunits [81, 94].

Biochemical studies using MjPAN, demonstrated that a tripeptide motif (HbYX, where Hb=a hydrophobic amino acid and x=any amino acid) located at the extreme C-terminus of the proteasomal ATPase was important for proteasome function. Removal of the MjPAN C-terminus dramatically reduced its ability to stimulate the TaCP-mediated degradation of a nine-residue long peptide substrate [83]. Importantly, this MjPAN variant retained wild type ATPase activity, unfoldase activity and ability to stimulate hydrolysis of small peptides by TaCPs [83]. Systematic mutation of the C-terminal residues of MjPAN demonstrated that both the length of this tail and penultimate tyrosine residue of the HbYX motif was absolutely essential for MjPAN to stimulate the TaCP-mediated degradation of LFP and, thus, CP gate opening (where LFP represents a nine residue peptide substrate) [83]. To further investigate this activation step, a tryptophan residue was introduced into either the Hb or X position of the HbYX motif in MjPAN, and analyzed by tryptophan fluorescence and polarization [83]. This approach provided further evidence that MjPAN could associate with TaCP and suggested that the C-terminal tail of MjPAN moves from an aqueous to a hydrophobic environment upon association. Interestingly, peptides based on the C-terminus of MjPAN could compete with MjPAN for TaCP binding and serve as “gate openers” based on their stimulation of TaCP-mediated hydrolysis of LFP [83]. In contrast, peptides based on the C-terminus of the non-ATPase 11S regulator PA26 were unable to open the TaCP gate but could compete with MjPAN for TaCP binding [83]. These findings were consistent with studies, which revealed docking of the C-terminal tail of PA26 to the CP was associated with binding of a distant activation domain of PA26 to a region of the α-subunit N-terminal tails that form the CP gate [81, 94]. Thus, MjPAN and PA26 appear to use a different mechanism to open the CP gate.

Structural studies have been performed to further understand how proteasomal ATPases with C-terminal HbYX motifs open CP gates. In particular, cryoelectron microscopy (cryoEM) has been used to identify sites in the TaCP that are bound by peptides mimicking the C-terminal tail of MjPAN and to determine the structures of the TaCP gate in the “closed” and “open” forms induced by these peptides (Fig. 11.5) (gated and ungated openings of 9 and 20 Å diameter, respectively) [85]. An artificial hybrid activator has also been constructed using the heptameric PA26 structure as a scaffold for attachment of eight residues corresponding to the C-terminal tail of MjPAN [86]. This hybrid activator is heptameric and forms a stable complex with the TaCP in which the activator caps both ends of the TaCP and opens the gate of the CP through an HbYX-dependent mechanism. Using single particle cryoEM and X-ray crystallography, the structure of the hybrid activator was determined in association with TaCP. In both studies [85, 86], residues corresponding to the MjPAN C-terminal tail were found to bind to the α-rings of TaCP in the ‘inter-subunit’ pocket (between the adjacent α-subunits) and induce and stabilize the open-gate conformation of TaCP. Although PA26 and MjPAN bind to a similar pocket on the CP, PA26 also requires binding to the CP α-subunit N-terminal tails, by a distant activation domain, to open and stabilize the CP gates [94, 95].

Interestingly, most haloarchaea and many methanogens are predicted to encode two distinct homologs of PAN, often one of which is lacking the conserved C-terminal HbYX motif. Thus, the C-terminal motif needed for CP interaction and gate opening, by PAN, may vary among archaeal species or alternatively archaea may synthesize PAN subtypes of different functions (e.g. PANs that unfold proteins but do not bind the CP or PANs that bind the CP but do not open the gates). Among the C-terminal sequences predicted for haloarchaeal PANs, ~43% include HbYX motifs, ~33% possess TFA motifs and ~23% harbour C-terminal tails that lack tyrosine or phenyalanine in the penultimate position. In H. volcanii, two PAN proteins have been identified, PAN-A with a C-terminal sequence, AFA and PAN-B with a C-terminal sequence, YQY [63]. As the penultimate tyrosine or phenyalanine of C-terminal tails appears essential for opening CP gates, the PAN-A and PAN-B proteins may have distinct roles in regulating proteasome-mediated degradation. Consistent with this possibility, a number of biological differences have been detected for the H. volcanii PAN-A and PAN-B proteins that support distinct functional roles. First, PAN-A is synthesized at high levels throughout growth, while the levels of PAN-B are low and induced several fold as cells transition to stationary phase [63]. In addition, while a phenotype for panB mutant strains has yet to be identified, deletion of panA renders cells more resistant to thermal stress and more sensitive to nitrogen limitation, hypo-osmotic stress, and exposure to L-canavanine [62]. In further support of functional differences between the two PAN proteins, the panA mutation can be complemented in trans by providing a wild type copy of panA but not panB [62].

Multiple Roles of the ATPase (PAN) in CP-Mediated Proteolysis

MjPAN is not only required for CP gate opening, but also for the unfolding and translocation of protein substrates for hydrolysis by the CP. Indeed “gateless” TaCP (containing αΔN subunits) still require MjPAN and ATP for the degradation of globular substrates (such as SsrA-tagged GFP) [82]. Thus, while the N-terminal tails of CP α-subunits appear to serve as a gate to prevent entry of large peptides as well as folded and unfolded proteins, removal of this gate is not sufficient to stimulate the degradation of structured proteins. This type of proteolysis still requires hydrolysis of ATP by an AAA + regulatory component, such as MjPAN in association with the CP.

Archaeal PAN X-ray Crystal Structures

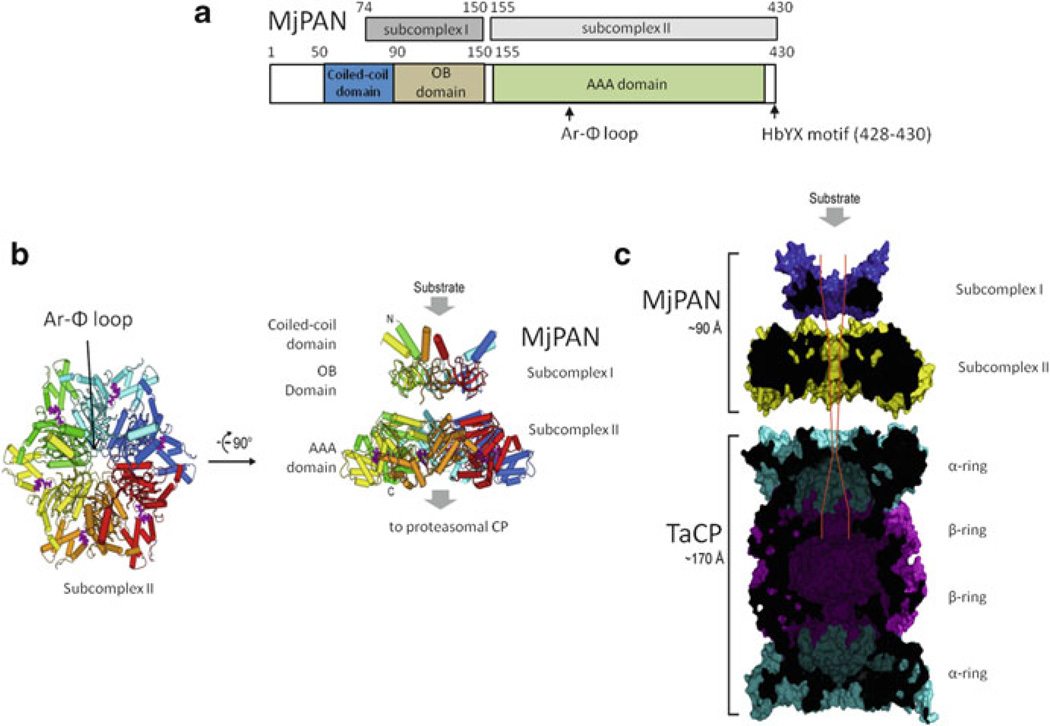

In the quest to solve the overall structure of an energy-dependent proteasome, a number of recent breakthroughs have been made examining the structure of various archaeal PAN subdomains. In one study, MjPAN was subjected to limited proteolysis resulting in the generation of two subcomplexes (I and II) that were amenable to X-ray crystallography [96]. Subcomplex I, which forms a stable hexamer, was derived from a fragment that spanned residues 74–150 including a portion of the predicted N-terminal coiled-coil (CC) domain (Fig. 11.6). In the subcomplex I structure (resolved to 2.1 Å), the CC domains of the six protein monomers formed pairs that protruded from a donut-shaped particle with an axial pore of 13 Å and an unexpected oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide binding (OB)-fold domain (Fig. 11.6) [96]. In contrast, subcomplex II, which dissociated into a mixture of hexamers to monomers, was composed of a fragment spanning residues 155–430 including the conserved AAA + domain and contained the C-terminal HbYX motif (Fig. 11.6). Given the level of conservation between MjPAN and the bacterial HslU, the atomic coordinates of MjPAN were superimposed onto the six subunits of HslU to generate a hexameric model for MjPAN (Fig. 11.6) [88, 90, 96]. Guided by these structures, a mutagenesis study, examined which amino acids and structural motifs were required for MjPAN function [84]. The structures of Archaeoglobus fulgidus PAN (AfPAN) N-terminal subdomain containing a eukaryotic GCN4 leucine zipper (in place of its CC-domain) has also helped to elucidate how folded proteins are degraded by archaeal proteasomes [97].

Fig. 11.6. Archaeal PAN subdomain structures provide a foundation for modelling the overall structure of an energy-dependent proteasome.

(a) and (b) Subcomplex I and II generated by limited proteolysis of MjPAN are indicated with the N-terminal coiled-coil (CC), OB fold and AAA domains highlighted. (c) Evidence supports the docking of MjPAN C-terminal tails with pockets formed at the α-α intersubunit interface of TaCPs. The N-terminal CC-domains are assumed to be distal to the CP and act as tentacles that grab protein substrates, thus, enabling the Ar-Φ loop within subcomplex II to grip regions of the substrate that extend through the pore formed by the OB fold domain. The Ar-Φ loop is also thought to undergo ATP-fuelled conformational changes resulting in pulling and tugging at the protein substrate while the OB fold domain provides a passive force that blocks the movement of folded protein structure through the pore. As the protein is unfolded by this mechanism, it is translocated through the ATPase into the central channel of the CP for degradation (Figure modified from [84] with permission)

Proteasome-Mediated Proteolysis

From a combination of structural and biochemical information, a complete view of how the proteasomal ATPase component functions in the unfolding of proteins for translocation into the CP for degradation is beginning to emerge. Based on electron micrographs of PAN:CP complexes and mass spectrometry of purified PAN complexes, archaeal PAN is thought to function as a hexameric complex [83, 98], with its C-terminal domain facing the cylindrical ends of four-stacked heptameric rings that form the CP (Fig. 11.6). The central channel of PAN is aligned with the gated central channel of the CP, to form a long tunnel with narrow restrictions for the passage of substrate proteins to the central proteolytic chamber. The N-domain of PAN is positioned distal to the CP with the N-terminal CC domains (one from each subunit) associating in pairs, to form three tentacles that appear to stretch out and search for protein substrates (or possibly protein partners). The OB domain forms a stable ringed-platform for this network of tentacles and a relatively narrow pore (16 Å in diameter) that is thought to function as a molecular sieve restricting access of folded proteins from entering the central channel of the ATPase. While early evidence suggested MjPAN could unfold proteins on its surface in the absence of translocation [99], more recent work supports a model in which proteins are unfolded by energy-dependent translocation through the ATPase ring and that this can be coupled to threading the protein into the CP for destruction [96, 100]. Consistent with a threading model, the Ar-Φ loop (where Ar is any aromatic amino acid and F symbol is any hydrophobic amino acid), also known as the pore-1 loop, lines the central passage of the AAA + domain and defines one of the constriction points proximal to the OB domain in the subcomplex II model (Fig. 11.6) [84, 96]. Similar to related AAA + proteins, the Ar-Φ loop of PAN is thought to facilitate protein unfolding by gripping and tugging the substrate protein into the ATPase channel by ATP fuelled motions of the AAA + domain [96, 101–105]. The OB domain is proposed to exert a passive force on protein unfolding by providing a pore with a stable platform that blocks the movement of folded protein structure through the pore as the Ar-Φ loops tug and pull the protein [84]. Ultimately, the unfolded protein is translocated for degradation by the proteolytic active sites sequestered within the central chamber of the CP.

Archaeal PAN – An Ordered Reaction Cycle

Interestingly, subunits of MjPAN appear to bind ATP in pairs, which results in distinct effects on proteasome function that imply an ordered reaction cycle. Subunits of MjPAN are thought to partner with subunits opposite each other, in the hexameric ring, team up and cycle around the ring like a clock between one of three different states including ATP bound, ADP bound and nucleotide free [106]. Thus, MjPAN subunit pairs mediate an ordered reaction cycle of ATP binding, hydrolysis and release that coordinates and drives conformational changes around the MjPAN ring. These ATP-driven conformational changes are proposed to be critical for MjPAN-mediated protein unfolding. In particular, the Ar-Φ loop within the channel of the MjPAN ring is thought to grip proteins, tugging them up and down with repeated cycles of ATP hydrolysis. Tugging the proteins through the pore formed by the OB-fold domain is likely to serve as a rigid platform for resisting the entry of protein structure and, thus, facilitating an unfolding process through the central channel of the PAN ATPase.

Non-ATPases Associated with Archaeal CPs

In addition to AAA + regulatory proteins such as PAN, archaeal CPs are also proposed to associate with non-ATPase components. Early evidence for this possibility, arose when a protein inhibitor was co-purified with T. acidophilum CP [107], however the identity of the 20 kDa subunit of the inhibitor remains to be determined. More recently, immature archaeal CPs (composed of β-subunits that retain the N-terminal propeptide due to a Thr to Ala active site mutation) have been shown in vitro, to associate with proteins of the DUF75 superfamily [108]. Archaea and eukaryotes typically encode at least two members of the DUF75 superfamily that form heterodimeric complexes [Pba1-Pba2 (yeast), PAC1-PAC2 (mammals) and PbaA-PbaB in the archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis] [108–111]. Interestingly, the archaeal PbaA and eukaryotic Pba1/PAC1 proteins all have a conserved C-terminal HbYX motif that is required for binding the immature CPs [108]. Based on site-directed mutagenesis, this C-terminal tail docks to the same surface pocket on the α-subunit of the CP that is used by ATPase activators such as MjPAN [108]. Unlike MjPAN which opens the CP gate, the DUF75 proteins do not appear to alter CP activity and instead are thought to shield proteasomal subunit intermediates from nonproductive associations until assembly is complete or protect the cell from misassembled complexes [109–111]. While DUF75 protein homologs are also found in actinobacteria, their function is thought to be distinct from the DUF75 proteins of Archaea and eukaryotes due to the addition of a large C-terminal domain and absence of a C-terminal HbYX motif [108].

Protein Modifications

Ubiquitylation and Its Role in Marking Proteins for Proteolysis by Proteasomes in Eukaryotes

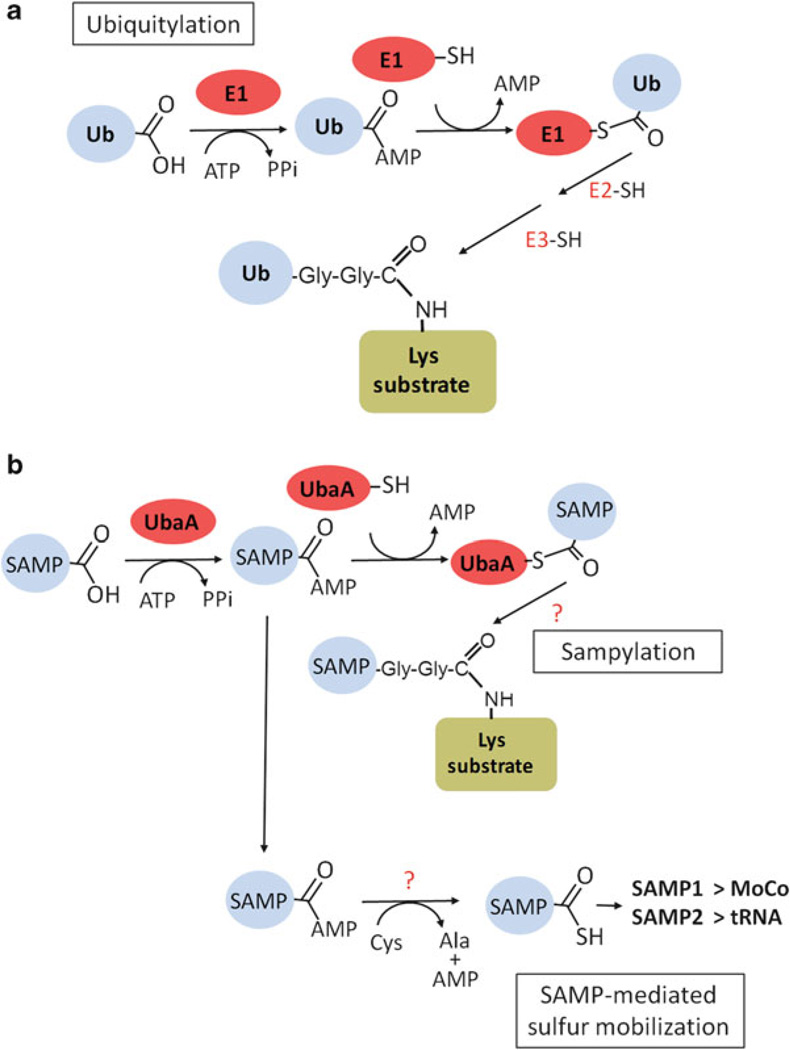

Ubiquitin is a highly conserved small protein modifier that is covalently attached to substrate proteins by a process termed ubiquitylation (Fig. 11.7a) [112]. Ubiquitylation involves the covalent attachment of the C-terminal carboxylate of Gly76 of ubiquitin to a protein substrate. Ubiquitin can be attached to proteins by an isopeptide bond to the ε-amino group of substrate lysine residues, a thioester bond to substrate cysteine residues, an oxy-ester bond to substrate serine or threonine residues, or peptide bond to the Nα-amino group of a protein substrate [113, 114]. The attachment of a single moiety of ubiquitin to a protein (mono-ubiquitylation) can alter the activity and/or location of the protein and can even signal the protein for destruction in lysosomes [115–117]. Chains of ubiquitin can also form through isopeptide bonds between the C-terminal carboxyl group of an incoming ubiquitin to one of the seven lysine residues of a ubiquitin (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48 and K63) moiety covalently attached to a protein substrate [118]. Of these chains, the K63- and K48-linked chains of ubiquitin are best characterized. The K63-linked ubiquitin chains have non-proteolytic roles such as signalling for sorting into the multivesicular body pathway [119], while the K48-linked ubiquitin chains typically target a protein for destruction by 26S proteasomes [120].

Fig. 11.7. Ubiquitylation and sampylation.

(a) Eukaryotes use an elaborate E1-E2-E3 mediated mechanism for the attachment of ubiquitin to protein substrates. (b) Similarly to eukaryotes, small archaeal ubiquitin-like modifier proteins (termed SAMPs) can form protein conjugates in the archaeon H. volcanii by a pathway that is dependent upon the synthesis of an E1 homolog (termed UbaA). Based on genome sequence, E2 and E3 homologs are not predicted for this pathway. UbaA and SAMP proteins appear to also be linked to sulfur incorporation pathways (such as the biosynthesis of MoCo and thiolated tRNA) that require an E1-type adenylation reaction for the formation of a thiocarboxylated sulfur carrier protein with a ubiquitin-type β-grasp fold

Ubiquitylation involves a series of enzyme catalyzed reactions with the formation of adenylated ubiquitin and thioester intermediates that result in the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to proteins (Fig. 11.7a) [121–123]. In the first step, a ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) adenylates the C-terminal carboxylate of Gly76 of ubiquitin (part of the a conserved diglycine motif, Gly75Gly76) in an ATP-dependent reaction that releases PPi. The adenylated form of ubiquitin is attacked by a conserved cysteine residue of E1 to form a thioester intermediate between the C-terminal Gly76 of ubiquitin and the conserved catalytic cysteine of the E1. In the next step, a conserved cysteine residue of an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) attacks the E1-ubiquitin thioester intermediate. This E2-mediated reaction results in the transfer of ubiquitin to the E2 enzyme and formation of a thioester bond between the E2 and the C-terminal Gly76 of ubiquitin. Finally, ubiquitin is transferred to the substrate protein with assistance from an ubiquitin ligase (E3). The E3 enzyme either directly transfers ubiquitin from E2 to the protein substrate or forms a thioester intermediate between a conserved cysteine of E3 and the C-terminal Gly76 of ubiquitin prior to transfer. In the formation of ubiquitin chains, the concerted action of the E1-E2-E3 enzymes is repeated with the transfer of ubiquitin to one of the seven lysine residues of ubiquitin that is attached to the modified protein [124]. In some cases, the ubiquitylation process is more elaborate with the use of a ubiquitin chain elongation factor termed an E4 [122], while other ubiquitylation events occur independent of an E3-ubiquitin ligase [125–127].

Multifunctional Roles of Proteins Related to Ubiquitin and E1 in Bacteria

While ubiquitin is not conserved, at the amino acid level, among either Archaea or bacteria, proteins with a predicted β-grasp ubiquitin-like fold are common to all organisms [128]. For example, the bacterial proteins ThiS and MoaD both exhibit a ubiquitin-like structure and have been extensively studied for their role in the incorporation of sulfur into thiamine and molybdenum cofactors, respectively [129, 130]. Additional biochemical roles for bacterial proteins with a ubiquitin-like structure have been identified that are independent of protein modification including QbsE-mediated thioquinolobactin siderophore biosynthesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens [131], CysO-mediated cysteine biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis [132, 133] and others [134].

Similar to eukaryotic ubiquitin, bacterial proteins with a ubiquitin-like fold can be activated at their C-terminus by enzymes of the E1-like superfamily [135]. For example, the bacterial E1 homologs, MoeB and ThiF, associate with and adenylate the C-terminal carboxylate of their cognate ubiquitin-like partner protein, MoaD and ThiS, respectively [136, 137]. However, in contrast to ubiquitin, the adenylated form of the bacterial ubiquitin-like proteins is typically modified by an E1-like enzyme to accept sulfur from either a cysteine desulfurase or rhodanese [138, 139]. This transfer of sulfur results in the formation of a C-terminal thiocarboxylated form of the ubiquitin-like protein that can be used as a source of activated-sulfur for biosynthetic reactions [140].

E1 and Ubiquitin-Like Protein Homologs of Archaea

While all Archaea encode homologs of E1 and proteins with a ubiquitin-like protein structure based on genome sequence, the role of these proteins in archaeal cell function has only recently been examined. Using the halophilic archaeon H. volcanii as a model system, two ubiquitin-like proteins, termed SAMP1 and SAMP2 (small archaeal modifier protein 1 and 2) and an E1 homolog (UbaA, ubiquitin-like activating protein of Archaea) were examined for their role in protein modification and/or sulfur incorporation into biomolecules such as molybdenum cofactor and tRNA (2-thiouracil) [141, 142]. Similar to most archaeal species, halophilic Archaea are predicted to synthesize biomolecules that require sulfur such as molybdenum/tungsten cofactors [143]. Furthermore, like most Archaea, H. volcanii is predicted to encode multiple ubiquitin-like proteins and a single E1 homolog, but not E2 or E3 homologs [144–146]. Thus, Archaea were anticipated to use ubiquitin-like proteins for sulfur incorporation into biomolecules and not for protein conjugation [128].

Sampylation – An Archaeal Form of Ubiquitylation

Recently it was shown that ubiquitin-like proteins can be conjugated to proteins in Archaea, by a process termed sampylation that is dependent upon the synthesis of an E1 homolog (Fig. 11.7b). These surprising findings are based on the following experimental evidence. Using H. volcanii as a model system, the ubiquitin-like proteins SAMP1 (87 a.a.) and SAMP2 (66 a.a.) were expressed with an N-terminal FLAG-tag and the formation of SAMP1/2 protein conjugates was analyzed by α-FLAG immunoblot [141]. Under certain growth conditions, an array of large α-FLAG specific protein bands was detected for both FLAG-SAMP1 and FLAG-SAMP2 expression strains [141]. Deletion of the conserved C-terminal diglycine motif of the ubiquitin-like protein or deletion of the ubaA gene (encoding the H. volcanii E1 homolog UbaA) abolished the ability to detect SAMP protein conjugates in H. volcanii cells [141, 142]. This effect could be complemented in trans by the wild type ubaA (but not by ubaA with a mutation in the conserved active site cysteine) suggesting that SAMP1 and SAMP2 are activated by an E1-like mechanism [142].

To determine the type of peptide bond formed between archaeal ubiquitin-like proteins and their protein substrates, SAMP2 was selected for further analysis [141], as it contains a lysine residue immediately preceding its C-terminal diglycine motif (i.e. KGG). The location of this lysine residue enabled the use of tryptic digestion and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) to analyze the SAMP2 protein conjugates, in a similar to approach to that used to analyze ubiquitylated proteomes of eukaryotes [147]. If an isopeptide bond was present, between the C-terminal carboxylate of Gly66 in SAMP2 and an internal lysine residue on the protein substrate, the modified lysine residue of the protein substrate would be resistant to cleavage by trypsin and hence retain the GG footprint derived from the SAMP2 C-terminus. With this approach, SAMP2-protein conjugates were isolated by α-FLAG affinity chromatography from an H. volcanii FLAG-SAMP2 expression strain (compared to the control strain) and isopeptide bonds were detected between Gly66 (of SAMP2) and the lysine residues of eight different proteins predicted to mediate a variety of functions, from metabolism to transcription [141]. Similar to ubiquitylation [148], SAMP2 modification (samp2ylation) was also detected on multiple sites within a single target protein (i.e. a TATA-box binding protein and tandem rhodanese domain protein) [141]. Furthermore, Gly66 of SAMP2 also formed an isopeptide bond with one of the two SAMP2 lysine residues (i.e. Lys58) revealing the presence of K58-linked SAMP2 chains [141]. Whether the SAMP2 chains are associated with a protein substrate remains to be determined. In eukaryotes, ubiquitin genes are translated into polypeptide chains of repeating units of ubiquitin fused head-to-tail [149–151] or ubiquitin fused to unrelated amino acid sequences [152]. These ubiquitin-protein fusions are cleaved by deubiquitylases to generate free pools of mature ubiquitin [153]. Unlike ubiquitin, SAMP2 is translated as a single protein. While speculative, it is possible that archaeal cells might regulate the pools of free SAMP2 by the synthesis and cleavage of unanchored SAMP2 chains. Alternatively, if SAMP2 chains are anchored, this might enhance the diversity of SAMP modifications available for protein targeting.

Using various strains of H. volcanii expressing either FLAG-SAMP1 or FLAG-SAMP2, together with α-FLAG immunoprecipitation, several interacting proteins were identified by tandem MS, following “in-gel” digested with trypsin [141]. Cells used for this analysis were grown in different culture conditions to enhance coverage of proteins modified by SAMP1 and/or SAMP2 (termed the “sampylome”). While SAMP modification sites were not mapped using this second approach, 32 proteins specific for the FLAG-SAMP expression strains were identified by MS/MS. These included the 8 proteins described above (with their SAMP2 modification sites mapped) as well as 24 additional homologs of proteins involved in ubiquitylation, sulfur incorporation, stress responses, metabolism and information processing such as transcription and translation [141].

Regulation of Sampylation

Environmental conditions can signal changes in the level of SAMP protein conjugates that are formed in H. volcanii cells. For example, growth in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide and other culture conditions can increase the levels of SAMP protein conjugates [141, 142]. Thus, sampylation is regulated, most likely at the posttranscriptional level, based on the use of a constitutive promoter for expression of the genes encoding the SAMP proteins throughout these experiments [141, 142].

Functional Role of Sampylation

Sampylation (the formation of SAMP protein conjugates) appears to mark some proteins for degradation by proteasomes in Archaea. However, the evidence supporting a biological connection between sampylation and proteasomes remains indirect. The first piece of evidence in support of this association is that SAMP1-modified proteins accumulate in H. volcanii cells that contain chromosomal deletions of the genes encoding the proteasomal CP α1-subunit (psmA) or the Rpt-like ATPase PAN-A (panA) [141]. Thus, SAMP1-modified proteins may not be efficiently degraded by proteasomes in these mutant cells. In addition to this finding, many of the proteins that are modified by SAMP1 and/or SAMP2 or associated with these SAMP proteins [141] were also found to accumulate in H. volcanii cells that are disrupted in proteasome function either by deletion of panA [154] or treatment with the proteasome-specific inhibitor clasto-Lactacystin β-lactone [155]. However, currently there is no direct evidence that sampylation of a protein leads to its degradation by the proteasome.

To further understand the role of sampylation in archaeal cell function, the genes encoding the ubiquitin-like protein modifiers (SAMP1 and SAMP2) and the E1 homolog (UbaA) were deleted from the genome of H. volcanii [142]. The resulting mutant strains were examined for biochemical and phenotypic differences compared to wild type cells. With this approach, UbaA was found to be required for the formation (or stabilization) of SAMP1 and SAMP2 protein conjugates in H. volcanii [142]. Thus, an E1-type mechanism of SAMP protein activation has been proposed (Fig. 11.7b).

In addition to protein conjugation, UbaA and SAMP2 appear essential for the thiolation of tRNA (most likely 2-thiouridine) based on comparison of tRNA from wild type and mutant cells, using [(N-acryloylamino)phenyl]mercuric chloride (APM) gel electrophoresis followed by hybridization to a specific probe for lysine tRNAs with anticodon UUU (tRNALysUUU) [142]. Because E1- and ubiquitin-like proteins can catalyze sulfur incorporation into tRNA in bacteria and eukaryotes [156, 157], the biochemical differences in the level of thiolated tRNA in H. volcanii ubaA and samp2 mutants (devoid of slow migrating “thiolated” tRNALysUUU) compared to wild type are thought to be independent of protein conjugation (Fig. 11.7b).

UbaA and SAMP1 also seem important for sulfur incorporation into the pterinbased molybdenum cofactor (MoCo) (Fig. 11.7b). This is based on the finding that, in comparison to wild type cells, ubaA and samp1 mutant cells are unable to grow under anaerobic conditions with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a terminal electron acceptor or produce DMSO reductase activity when switched to anaerobic conditions with DMSO [142]. DMSO reductase requires incorporation of MoCo into the catalytic subunit DmsA for activity. Similarly to wild type, the ubaA and samp1 mutant strains were still able to produce transcript specific for dmsA (encoding the catalytic subunit of DMSO reductase).

Together, these results suggest UbaA and SAMP proteins mediate not only sampylation but also sulfur incorporation into tRNA and MoCo (Fig. 11.7b). The E1 homolog, UbaA, appears at the crossroads of activating the SAMP proteins for formation of an isopeptide bond between the C-terminal carboxylate of SAMP and the target protein and for the formation of a putative C-terminal thiocarboxylate group on the SAMP1 and SAMP2 proteins for sulfur transfer to MoCo and tRNA, respectively. Thus, any phenotypic differences that are detected for archaeal mutants of E1 and ubiquitin-like homologs (in comparison to wild type cells) will need to be further examined for whether these changes are due to perturbations in sampylation (protein conjugation) or sulfur transfer to biomolecules.

Summary

While Archaea are often thought of as prokaryotes, due to the absence of a membrane-bound nucleus, these incredible microbes have self-compartmentalized proteases and protein conjugation systems that are closely related to the ubiquitin-proteasome systems of eukaryotes. Unlike bacteria, which have multiple energy-dependent proteases in their cytosol [i.e. Lon, Clp and HslUV (or proteasomes in actinobacteria)], Archaea appear highly dependent on the proteasome system (with an unknown contribution by the membrane-bound Lon protease) as their major energy-dependent proteases. Based on numerous studies that have investigated how archaeal PAN and CP complexes function at the atomic level, an elaborate mechanism of how proteasomes degrade unfolded and/or folded proteins is rapidly emerging. Surprisingly, Archaea also contain a system in which ubiquitin-like proteins are conjugated to substrate proteins, through an apparent E1-like mechanism termed sampylation. Sampylation is predicted to exist in all Archaea and occurs independent of E2 or E3 homologs. Whether or not sampylation marks proteins for degradation by the proteasome remains to be determined; however, indirect evidence suggests these two pathways are functionally connected. Improving our understanding of how proteins are targeted for degradation in archaea promises to be an exciting area of research. Sampylation is likely a simplified system for the covalent marking proteins, which has close evolutionary roots to ubiquitylation and other related pathways that play an important role in eukaryotic cell function. Interestingly, more elaborate protein conjugation mechanisms than sampylation may exist in a select group of bacteria and archaea that harbour E1, E2 and E3 homologs, based on recent metagenomic sequencing and comparative genomics [144, 158].

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM57498) and the Department of Energy Office of Basic Energy Sciences (DE-FG02-05ER15650).

References

- 1.Gottesman S. Regulation by proteolysis: developmental switches. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2(2):142–147. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf DH, Hilt W. The proteasome: a proteolytic nanomachine of cell regulation and waste disposal. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695(1–3):19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lupas A, Flanagan JM, Tamura T, Baumeister W. Self-compartmentalizing proteases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22(10):399–404. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cha SS, An YJ, Lee CR, Lee HS, et al. Crystal structure of Lon protease: molecular architecture of gated entry to a sequestered degradation chamber. EMBO J. 2010;29(20):3520–3530. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Effantin G, Maurizi MR, Steven AC. Binding of the ClpA unfoldase opens the axial gate of ClpP peptidase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(19):14834–14840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee ME, Baker TA, Sauer RT. Control of substrate gating and translocation into ClpP by channel residues and ClpX binding. J Mol Biol. 2010;399(5):707–718. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith DM, Benaroudj N, Goldberg A. Proteasomes and their associated ATPases: a destructive combination. J Struct Biol. 2006;156(1):72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ammelburg M, Frickey T, Lupas AN. Classification of AAA + proteins. J Struct Biol. 2006;156(1):2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuwald AF, Aravind L, Spouge JL, Koonin EV. AAA+: a class of chaperone-like ATPases associated with the assembly, operation, and disassembly of protein complexes. Genome Res. 1999;9(1):27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sauer RT, Baker TA. AAA+ proteases: ATP-fueled machines of protein destruction. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:587–612. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060408-172623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gur E, Ottofuelling R, Dougan DA. Machines of destruction − AAA + proteases and the adaptors that control them. In: Dougan DA, editor. Regulated proteolysis in microorganisms. Vol. 66. Springer: Subcell Biochem; 2013. pp. 3–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samanovic M, Li H, Darwin KH. The Pup-Proteasome system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. In: Dougan DA, editor. Regulated proteolysis in microorganisms. Vol. 66. Springer: Subcell Biochem; 2013. pp. 267–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maupin-Furlow JA, Humbard MA, Kirkland PA, Li W, et al. Proteasomes from structure to function: perspectives from Archaea. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2006;75:125–169. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)75005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bar-Nun S, Glickman MH. Proteasomal AAA-ATPases: structure and function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823(1):67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Besche H, Tamura N, Tamura T, Zwickl P. Mutational analysis of conserved AAA+ residues in the archaeal Lon protease from Thermoplasma acidophilum. FEBS Lett. 2004;574(1–3):161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukui T, Eguchi T, Atomi H, Imanaka T. A membrane-bound archaeal Lon protease displays ATP-independent proteolytic activity towards unfolded proteins and ATP-dependent activity for folded proteins. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(13):3689–3698. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.13.3689-3698.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Mot R, Nagy I, Walz J, Baumeister W. Proteasomes and other self-compartmentalizing proteases in prokaryotes. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7(2):88–92. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01432-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lupas A, Zuhl F, Tamura T, Wolf S, et al. Eubacterial proteasomes. Mol Biol Rep. 1997;24(1–2):125–131. doi: 10.1023/a:1006803512761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lupas A, Zwickl P, Baumeister W. Proteasome sequences in eubacteria. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19(12):533–534. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tamura T, Nagy I, Lupas A, Lottspeich F, et al. The first characterization of a eubacterial proteasome: the 20S complex of Rhodococcus. Curr Biol. 1995;5(7):766–774. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bochtler M, Ditzel L, Groll M, Hartmann C, et al. The proteasome. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:295–317. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voges D, Zwickl P, Baumeister W. The 26S proteasome: a molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:1015–1068. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsen CN, Finley D. Protein translocation channels in the proteasome and other proteases. Cell. 1997;91(4):431–434. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80427-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brannigan JA, Dodson G, Duggleby HJ, Moody PC, et al. A protein catalytic framework with an N-terminal nucleophile is capable of self-activation. Nature. 1995;378(6555):416–419. doi: 10.1038/378416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekici OD, Paetzel M, Dalbey RE. Unconventional serine proteases: variations on the catalytic Ser/His/Asp triad configuration. Protein Sci. 2008;17(12):2023–2037. doi: 10.1110/ps.035436.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oinonen C, Rouvinen J. Structural comparison of Ntn-hydrolases. Protein Sci. 2000;9(12):2329–2337. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.12.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seemuller E, Lupas A, Stock D, Lowe J, et al. Proteasome from Thermoplasma acidophilum: a threonine protease. Science. 1995;268(5210):579–582. doi: 10.1126/science.7725107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dodson G, Wlodawer A. Catalytic triads and their relatives. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23(9):347–352. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kisselev AF, Songyang Z, Goldberg AL. Why does threonine, and not serine, function as the active site nucleophile in proteasomes? J Biol Chem. 2000;275(20):14831–14837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.14831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maupin-Furlow JA, Aldrich HC, Ferry JG. Biochemical characterization of the 20S proteasome from the methanoarchaeon Methanosarcina thermophila. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(6):1480–1487. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1480-1487.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zwickl P, Kleinz J, Baumeister W. Critical elements in proteasome assembly. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1(11):765–770. doi: 10.1038/nsb1194-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Groll M, Heinemeyer W, Jager S, Ullrich T, et al. The catalytic sites of 20S proteasomes and their role in subunit maturation: a mutational and crystallographic study. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(20):10976–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.10976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jager S, Groll M, Huber R, Wolf DH, et al. Proteasome beta-type subunits: unequal roles of propeptides in core particle maturation and a hierarchy of active site function. J Mol Biol. 1999;291(4):997–1013. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bauer MW, Bauer SH, Kelly RM. Purification and characterization of a proteasome from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63(3):1160–1164. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1160-1164.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dahlmann B, Kopp F, Kuehn L, Niedel B, et al. The multicatalytic proteinase (prosome) is ubiquitous from eukaryotes to archaebacteria. FEBS Lett. 1989;251(1–2):125–131. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maupin-Furlow JA, Ferry JG. A proteasome from the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(48):28617–28622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson HL, Aldrich HC, Maupin-Furlow J. Halophilic 20S proteasomes of the archaeon Haloferax volcanii: purification, characterization, and gene sequence analysis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(18):5814–5824. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.18.5814-5824.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arendt CS, Hochstrasser M. Eukaryotic 20S proteasome catalytic subunit propeptides prevent active site inactivation by N-terminal acetylation and promote particle assembly. EMBO J. 1999;18(13):3575–3585. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwon YD, Nagy I, Adams PD, Baumeister W, et al. Crystal structures of the Rhodococcus proteasome with and without its pro-peptides: implications for the role of the pro-peptide in proteasome assembly. J Mol Biol. 2004;335(1):233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuhl F, Seemuller E, Golbik R, Baumeister W. Dissecting the assembly pathway of the 20S proteasome. FEBS Lett. 1997;418(1–2):189–194. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01370-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li D, Li H, Wang T, Pan H, et al. Structural basis for the assembly and gate closure mechanisms of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 20S proteasome. EMBO J. 2010;29(12):2037–2047. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin G, Hu G, Tsu C, Kunes YZ, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis prcBA genes encode a gated proteasome with broad oligopeptide specificity. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59(5):1405–1416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.05035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson HL, Ou MS, Aldrich HC, Maupin-Furlow J. Biochemical and physical properties of the Methanococcus jannaschii 20S proteasome and PAN, a homolog of the ATPase (Rpt) subunits of the eucaryal 26S proteasome. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(6):1680–1692. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1680-1692.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaczowka SJ, Maupin-Furlow JA. Subunit topology of two 20S proteasomes from Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(1):165–174. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.1.165-174.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ginzburg M, Sachs L, Ginzburg BZ. Ion metabolism in a Halobacterium. I. Influence of age of culture on intracellular concentrations. J Gen Physiol. 1970;55(2):187–207. doi: 10.1085/jgp.55.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mevarech M, Frolow F, Gloss LM. Halophilic enzymes: proteins with a grain of salt. Biophys Chem. 2000;86(2–3):155–164. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(00)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Falb M, Aivaliotis M, Garcia-Rizo C, Bisle B, et al. Archaeal N-terminal protein maturation commonly involves N-terminal acetylation: a large-scale proteomics survey. J Mol Biol. 2006;362(5):915–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirkland PA, Humbard MA, Daniels CJ, Maupin-Furlow JA. Shotgun proteomics of the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(11):5033–5039. doi: 10.1021/pr800517a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Soppa J. Protein acetylation in archaea, bacteria, and eukaryotes. Archaea. 2010;2010:9. doi: 10.1155/2010/820681. (Article ID 820681) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kisselev AF, Akopian TN, Goldberg AL. Range of sizes of peptide products generated during degradation of different proteins by archaeal proteasomes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(4):1982–1989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.4.1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kisselev AF, Akopian TN, Woo KM, Goldberg AL. The sizes of peptides generated from protein by mammalian 26 and 20S proteasomes. Implications for understanding the degradative mechanism and antigen presentation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(6):3363–3371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gallastegui N, Groll M. The 26S proteasome: assembly and function of a destructive machine. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35(11):634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vigneron N, Van den Eynde BJ. Proteasome subtypes and the processing of tumor antigens: increasing antigenic diversity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(1):84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zwickl P, Grziwa A, Puhler G, Dahlmann B, et al. Primary structure of the Thermoplasma proteasome and its implications for the structure, function, and evolution of the multicatalytic proteinase. Biochemistry. 1992;31(4):964–972. doi: 10.1021/bi00119a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zwickl P, Lottspeich F, Baumeister W. Expression of functional Thermoplasma acidophilum proteasomes in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1992;312(2–3):157–160. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80925-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kocabiyik S, Ozdemir I, Zwickl P, Ozdogan S. Molecular cloning and co-expression of Thermoplasma volcanium proteasome subunit genes. Protein Expr Purif. 2010;73(2):223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Medalia N, Sharon M, Martinez-Arias R, Mihalache O, et al. Functional and structural characterization of the Methanosarcina mazei proteasome and PAN complexes. J Struct Biol. 2006;156(1):84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Groll M, Brandstetter H, Bartunik H, Bourenkow G, et al. Investigations on the maturation and regulation of archaebacterial proteasomes. J Mol Biol. 2003;327(1):75–83. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robb FT, Maeder DL, Brown JR, DiRuggiero J, et al. Genomic sequence of hyperthermophile, Pyrococcus furiosus: implications for physiology and enzymology. Methods Enzymol. 2001;330:134–157. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)30372-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Madding LS, Michel JK, Shockley KR, Conners SB, et al. Role of the beta1 subunit in the function and stability of the 20S proteasome in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(2):583–590. doi: 10.1128/JB.01382-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou G, Kowalczyk D, Humbard MA, Rohatgi S, et al. Proteasomal components required for cell growth and stress responses in the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(24):8096–8105. doi: 10.1128/JB.01180-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karadzic I, Maupin-Furlow J, Humbard M, Prunetti L, Singh P, Goodlett DR. Chemical cross-linking, mass spectrometry, and in silico modeling of proteasomal 20S core particles of the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. Proteomics. 2012;12(11):1806–1814. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reuter CJ, Kaczowka SJ, Maupin-Furlow JA. Differential regulation of the PanA and PanB proteasome-activating nucleotidase and 20S proteasomal proteins of the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(22):7763–7772. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7763-7772.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Humbard MA, Reuter CJ, Zuobi-Hasona K, Zhou G, et al. Phosphorylation and methylation of proteasomal proteins of the haloarcheon Haloferax volcanii. Archaea. 2010;2010:481725. doi: 10.1155/2010/481725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Humbard MA, Stevens SM, Jr, Maupin-Furlow JA. Posttranslational modification of the 20S proteasomal proteins of the archaeon Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(21):7521–7530. doi: 10.1128/JB.00943-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Humbard MA, Zhou G, Maupin-Furlow JA. The N-terminal penultimate residue of 20S proteasome alpha1 influences its N(alpha) acetylation and protein levels as well as growth rate and stress responses of Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(12):3794–3803. doi: 10.1128/JB.00090-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stadtmueller BM, Hill CP. Proteasome activators. Mol Cell. 2011;41(1):8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Finley D, Tanaka K, Mann C, Feldmann H, et al. Unified nomenclature for subunits of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteasome regulatory particle. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23(7):244–245. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01222-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Glickman MH, Rubin DM, Coux O, Wefes I, et al. A subcomplex of the proteasome regulatory particle required for ubiquitin-conjugate degradation and related to the COP9-signalosome and eIF3. Cell. 1998;94(5):615–623. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]