Abstract

The skeleton serves as the principal site for hematopoiesis in adult terrestrial vertebrates. The function of the hematopoietic system is to maintain homeostatic levels of all circulating blood cells, including myeloid cells, lymphoid cells, red blood cells, and platelets. This action requires the daily production of more than 500 billion blood cells every day. The vast majority of these cells are synthesized in the bone marrow, where they arise from a limited number of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that are multipotent and capable of extensive self-renewal. These attributes of HSCs are best demonstrated by marrow transplantation, where even a single HSC can repopulate the entire hematopoietic system. HSCs are therefore adult stem cells capable of multilineage repopulation, poised between cell fate choices, which include quiescence, self-renewal, differentiation and apoptosis. While HSC fate choices are in part determined by multiple stochastic fluctuations of cell autonomous processes, according to the niche hypothesis, signals from the microenvironment are also likely to determine stem cell fate. While it had long been postulated that signals within the bone marrow could provide regulation of hematopoietic cells, it is only in the past decade that advances in flow cytometry and genetic models have allowed for a deeper understanding of microenvironmental regulation of HSCs. In this review, we will highlight the cellular regulatory components of the HSC niche.

Anatomic distribution of cell types in the bone marrow

In all vertebrates except fish, in which hematopoiesis occurs in the kidney, the bone marrow is the hematopoietic organ (Hartenstein 2006). The skeleton contains all cells of the osteolineage cells, from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (also called skeletal stem cells (Bianco, Robey et al. 2010)), to chondrocytes, osteoprogenitors, osteoblasts and osteocytes. Osteoblasts form a layer, the endosteum, at the interface between the mineralized bone and the bone marrow contained within its center. At these endosteal sites, a population of F4/80+ macrophages (osteomacs) forms a canopy over mature osteoblasts at sites of bone formation (Chang, Raggatt et al. 2008). Arteriolar vessels, capillaries, and endothelium-bound venous sinuses branch throughout the bone marrow. Endothelial cells, macrophages, osteolineage, and stromal (also called reticular) cells that crisscross the space between vessels and endosteum form a three-dimensional scaffold that supports clusters of blood-forming cells as well as marrow adipose tissue (Fazeli, Horowitz et al. 2013), providing the complex marrow microenvironment that regulates hematopoiesis (Hartenstein 2006). HSC-derived cells that lose contact with their niche cells progress toward more differentiated stages, becoming committed progenitors and then precursors for lymphoid cells, red blood cells, thrombocytes, granulocyte/monocytes and granulocytes. These differentiating HSC progeny cells are then found nearer the center of the bone marrow, where they proliferate and form growing colonies of maturing blood cells. Once matured, blood cells cross the endothelium into the bloodstream. Immature lymphoid progenitors leave the bone marrow to populate the thymus and lymphoid organs, where they further differentiate (Hartenstein 2006).

The anatomic localization of HSCs in the bone marrow is controversial. Initial studies using transplanted labeled HSC-enriched cell populations suggested that HSCs preferentially localize to endosteal regions (Zhang, Niu et al. 2003; Wilson, Murphy et al. 2004; Xie, Yin et al. 2009). In contrast, in situ localization of HSCs using SLAM markers (CD150+ CD48− CD41− lineage−), suggests that the majority of HSCs are in contact with sinusoidal endothelium at bone-distant sites (Kiel, Yilmaz et al. 2005). HSCs are in direct contact with perivascular CXCL12-abundant reticular (CAR) cells (Sugiyama, Kohara et al. 2006) and nestin-GFP+ stromal cells (Mendez-Ferrer, Michurina et al. 2010), providing further support for a perivascular HSC localization. High resolution three-dimensional imaging of the vasculature in murine long bones provides a potential explanation for these divergent observations (Nombela-Arrieta, Pivarnik et al. 2013). Specifically, the endosteal region is highly vascular and most phenotypic HSCs are perivascular, whether localized to the endosteum or bone-distant sites.

The concept of the niche

HSC fate choices are determined in part by multiple stochastic fluctuations of cell autonomous processes (Cantor and Orkin 2001; Enver, Pera et al. 2009; Graf and Enver 2009). In addition, according to the niche hypothesis, signals from the microenvironment are also likely to determine stem cell fate. Schofield (Schofield 1978), in response to observations on the hematopoietic system, first proposed the concept of the niche, where specific niche cells establish close interactions with immature cells which can enforce stem cell behavior. This idea was supported by initial anatomical studies which demonstrated hierarchical distribution of hematopoietic cells in marrow cavities (Lord, Testa et al. 1975; Gong 1978). This anatomical compartmentalization is highlighted by more recent homing studies demonstrating the localization of labeled immature cells to endosteal sites, both postmortem and intravitally (Nilsson, Dooner et al. 1997; Nilsson, Johnston et al. 2001; Lo Celso, Fleming et al. 2009; Xie, Yin et al. 2009). However, in spite of the instructive role of hematopoietic development in the inception of the niche hypothesis, it would take a quarter century before the role of the niche in HSC regulation could be proven in vivo, partially due to the complexity of the marrow microenvironment, which we outline below. Instead niche stem cell interactions would first be demonstrated in the drosophila gonad (Kai and Spradling 2003), and found to be important for adult stem cells in skin, brain, intestine as well as eventually bone marrow (Fuchs, Tumbar et al. 2004; Losick, Morris et al. 2011).

Developmental migration of HSCs and homing to intramedullary sites

During development, HSCs are first identified in the aorta-gonad-mesonephron region (Medvinsky and Dzierzak 1996; Dzierzak and Speck 2008). These cells then migrate to the fetal liver and to fetal bone (Dzierzak 1999). Skeletal sites remain the sole physiologic regions of active hematopoiesis throughout adult life. At these sites, the enormous hematopoietic activity initiated by the HSCs results in the daily production of more than 500 billion blood cells every day (Fliedner 2002). The vast majority of these hematopoietic progeny cells is synthesized in the bone marrow, and arises from a limited number (1–5/105 marrow cells) of HSCs. Proof-of-principle experiments have demonstrated that even a single HSC can repopulate the entire hematopoietic system (Osawa, Hanada et al. 1996). Direct visualization suggests that immature hematopoietic cells are found in relatively fixed positions in the marrow (Suzuki, Ohneda et al. 2006; Lo Celso, Fleming et al. 2009). In addition, a subpopulation of HSCs is continuously mobilized through the circulation (Storb, Graham et al. 1977; Wright, Wagers et al. 2001; Wagers, Sherwood et al. 2002). Interestingly, cell autonomous motility contributes to egress of HSCs from the microenvironment (Lapid, Itkin et al. 2013). HSC mobilization is also dependent on fluctuating levels of microenvironmental CXCL12 (Katayama, Battista et al. 2006) and is regulated by circadian rhythms (Mendez-Ferrer, Lucas et al. 2008), at least in part enforced centrally through the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). The ability of HSCs to be mobilized and to home to the marrow through the action of the chemokine CXCL12 and its receptor CXCR4 is fundamental for the therapeutic use of HSCs for bone marrow transplantation. Therefore, as we will review, one of the research strategies to identify niche components has focused on cell populations capable of secreting CXCL12.

Non-hematopoietic HSC niche components

Osteolineage cells

Early anatomic studies elucidated the endosteal distribution of HSCs (Lord, Testa et al. 1975; Gong 1978). In addition, in vivo, long term HSCs tightly adhere to endosteal matrix (Haylock, Williams et al. 2007). Based on this localization of HSCs, cells of the osteoblastic lineage (to which we will refer to throughout this review as osteolineage cells) were the first cellular marrow component considered as the critical HSC niche constituent. In vitro, osteoblastic cells support HSC activity (Taichman and Emerson 1994; Taichman, Reilly et al. 1996). Loss of osteolineage cells disrupts hematopoiesis (Visnjic, Kalajzic et al. 2001; Visnjic, Kalajzic et al. 2004). Moreover, osteolineage cells produce many factors important for hematopoiesis (Marusic, Kalinowski et al. 1993; Taichman and Emerson 1994; Calvi, Adams et al. 2003), both secreted as well as cell bound (Taichman, Reilly et al. 1996; Arai, Hirao et al. 2004; Weber, Forsythe et al. 2006; Jung, Wang et al. 2007; Qian, Buza-Vidas et al. 2007; Yoshihara, Arai et al. 2007). Our laboratory and others provided initial in vivo evidence of phenotypic and functional HSC expansion through targeted activation of the osteoblastic cell lineage (Calvi, Adams et al. 2003; Adams, Martin et al. 2007; Mendez-Ferrer, Michurina et al. 2010; Bromberg, Frisch et al. 2012). In these murine models, osteolineage cells are activated either genetically, in a transgenic mouse model of constitutively active parathyroid hormone (PTH) signaling driven by the 2.3 kilobases fragment of the alpha1(I) collagen gene promoter (Calvi, Sims et al. 2001), or by intermittent systemic administration of PTH(1–34) (Calvi, Adams et al. 2003; Bromberg, Frisch et al. 2012). Intermittent PTH treatment is bone anabolic (reviewed in(Goltzman 2008)). Consistent with a PTH-dependent effect on HSCs, patients with parathyroid adenomas and increased PTH levels have increased circulation of phenotypically-defined HSCs and endothelial progenitor cells (Ballen, Shpall et al. 2007; Brunner, Theiss et al. 2007). Simultaneously, Zhang et al. found that conditional inactivation of Bone Morphogenic Protein receptor IA resulted in greater trabecular bone and expansion of osteolineage cells, with a similar increase in HSCs (Zhang, Niu et al. 2003). However, general expansion of osteoblastic cells is not sufficient to increase HSCs (Lymperi, Horwood et al. 2008). This observation is also supported by data on a murine model of fibrous dysplasia characterized by massive increases in trabecular bone which demonstrated reduced HSCs, lineage-specific defects in megakaryocyte and erythrocyte development and impaired hematopoietic recovery from myeloablative injury (Schepers, Hsiao et al. 2012). On the other hand, general disruption of osteolineage cells in a murine model of inflammatory arthritis is not sufficient to impair HSCs (Ma, Park et al. 2009). These data suggest that specific stages of osteoblastic differentiation may provide different HSC support and that multiple osteolineage cell populations are likely to play different roles in hematopoiesis. This concept is further supported by data suggesting that, while multiple osteolineage subsets supported HSC long term reconstitution activity, some subsets mostly support HSC adhesion and homing, while others produce pro-HSC cytokines (Nakamura, Arai et al. 2010).

Multiple laboratories have contributed to an increased understanding of the diverse roles of osteolineage heterogeneity in support of HSCs by the microenvironment (Chitteti, Cheng et al. 2010; Chitteti, Cheng et al. 2010; Chitteti, Cheng et al. 2010; Nakamura, Arai et al. 2010; Cheng, Chitteti et al. 2011). The concept began developing that immature osteolineage cells are critical to HSC regulation. For example, data suggest that expression of Runx2, a transcription factor most highly expressed at early stages of osteoblast differentiation, appears to identify an osteoblastic population with greater HSC maintenance and enhancement potential (Chitteti, Cheng et al. 2010; Cheng, Chitteti et al. 2011). Conversely, when terminally differentiated osteoblastic cells or osteocytes are activated by constitutive PTH signaling, HSC frequency and function are unchanged, in spite of increased osteoblastic cells and trabecular bone (Calvi, Bromberg et al. 2012). In fact, agents that stimulate osteoblastic differentiation may be detrimental to HSC retention at the endosteum as evidenced by a shift in HSC localization to the vasculature (Yoon, Cho et al. 2012),(Xiao, Liu et al. 2009). Together these reports demonstrate heterogeneity in the osteoblastic cell pool with respect to its HSC-supportive properties, which appear to be dependent at least in part on osteoblastic differentiation stage.

One subset of osteolineage cells which has been controversial in its support of HSCs is the N-cadherin+ pool of osteolineage cells. Cadherins are calcium-dependent homotypic adhesion molecules that form adherens junctions. They are essential in fate specification of germline stem cells (Song, Zhu et al. 2002). Several reports implicate N-cadherin (N-CAD) in osteoblastic-HSC regulation (Zhang, Niu et al. 2003; Arai, Hirao et al. 2004; Wilson, Murphy et al. 2004). Moreover, knockdown of N-Cadherin in HSCs suppresses their long term engraftment (Hosokawa, Arai et al. 2010). Yet this work has been controversial (reviewed in (Levesque 2012)). Ncad expression increases with age in HSCs and in endosteal cells populations (Hosokawa, Arai et al. 2010), potentially explaining inconsistencies among various N-CAD studies. Our laboratory examined the bone and hematopoietic phenotypes of Ncad deletion from mature osteoblastic cells in both young and aged mice (Bromberg, Frisch et al. 2012). Loss of N-CAD corresponded to an age-dependent decrease in mineralized bone, suggestive of N-CAD involvement in terminal osteoblastic maturation, but we observed no change in HSC number or function at any age examined. In spite of speculation that the N-CAD+ osteoblastic population, which expands rapidly in response to injury (Dominici, Rasini et al. 2009), may be involved in HSC recovery from myeloablation, mice lacking osteoblastic N-CAD have no change in recovery from myeloablative injury (Bromberg, Frisch et al. 2012). Similarly, osteoblastic N-CAD was not required for the PTH-dependent HSC expansion (Bromberg, Frisch et al. 2012). These results are consistent with a companion report in which Ncad was deleted from immature OBs using an osterix-driven cre recombinase model (Greenbaum, Revollo et al. 2012). HSC number, cell cycle status, long-term repopulating activity, and self-renewal capacity were normal. Moreover, engraftment of wildtype cells into N-cadherin-deleted recipients was normal, as was G-CSF induced hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) mobilization. Together, these data show that N-cadherin expression in osteoblast lineage cells is dispensable for HSC maintenance in mice.

While not directly required for HSC maintenance, N-CAD expression marks a stromal cell population that does affect HSCs. Ncad expression was found to increase up to 8.5 fold following stimulation with dimethyl prostaglandin E2 (dmPGE2) a synthetic analog of the inflammatory mediator prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) known to have effects on HSC survival and proliferation (North, Goessling et al. 2007; Frisch, Porter et al. 2009; Goessling, Allen et al. 2011; Porter, Georger et al. 2013). Furthermore, N-CAD identifies osteoprogenitor cell sources of HSC-active non-canonical Wnt ligands and inhibitors of canonical Wnt signaling at homeostasis (Sugimura, He et al. 2012). Specifically, disruption of non-canonical Wnt signaling through the cadherin adhesion molecule Flamingo and/or Frizzled8 using genetic models resulted in decreased frequencies and absolute numbers of HSCs, with increased HSC cycling and reduced frequency of quiescent HSCs in contact with N-CAD+ osteolineage cells (Sugimura, He et al. 2012). These studies underscore the role of non-canonical Wnt signaling in maintaining HSC quiescence at the endosteum.

Of note, strategies for hormonal osteolineage stimulation may not only provide translational therapy to manipulate the niche and therefore HSCs, but may also indicate additional niche components. For example, studies had demonstrated the role of T-cells in the anabolic action of PTH on the skeleton (Terauchi, Li et al. 2009; Tawfeek, Bedi et al. 2010; Bedi, Li et al. 2012). Based on these data, the same group went on to show that T cells mediate the PTH-dependent expansion of short-term HSCs through Wnt10b, resulting in Wnt signaling activation of both stroma and HSCs (Li, Adams et al. 2012).

Osteolineage cells may also represent a target for signals produced by malignancies involving the bone marrow (e.g. Multiple myeloma and leukemia), which may disrupt the normal HSC niche. For example, dkk1 and CCL3 production by multiple myeloma initiate not only osteoclastic activation, but also osteoblastic inhibition (Qiang, Chen et al. 2008; Fulciniti, Tassone et al. 2009; Vallet, Pozzi et al. 2011; Vallet, Pozzi et al. 2011). This concept was also demonstrated in a xenograft model of leukemia (Colmone, Amorim et al. 2008). Our laboratory recently demonstrated that leukemia disrupts the osteoblastic microenvironment, and identified CCL3 as a commonly secreted product of human myelogenous leukemia (Frisch, Ashton et al. 2012). In addition, the niche may serve as a target for malignant cells that metastasize in the marrow microenvironment. Work from Shiozawa et al. demonstrated in a xenograft model that human prostate cancer (PCa) cells directly compete with HSCs for occupancy of the mouse HSC niche (Shiozawa, Pedersen et al. 2011). In addition PCa cells could then be mobilized into the circulation using HSC mobilization protocols. Of note, these data do not discriminate between cellular components of the normal niche, therefore the occupancy of the HSC niche by cancer cells may not restricted to the osteoblastic niche and likely occurs at any other anatomical sites in which a HSC microenvironment is established. Together, these data suggest that definition of the normal HSC niche may also have important therapeutic implication in pathologic conditions. Therefore, targeting the niche may provide a strategy in the treatment of leukemia or potentially other malignancies that affect the bone marrow.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Numerous experiments have demonstrated the important role of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), the multipotent stromal cells that give rise to the osteogenic lineage, as well as the adipocytes and chondrocytes, as active components of the HSC niche. This cell population has been difficult to define, in part because of its heterogeneity and the lack of consensus on its defining characteristics (adherence to plastic vs functional characteristics vs cell surface markers). Additional confusion is added by the use of the MSC abbreviation to designate preparations of human mesenchymal stromal precursor cells, which are now commercially available (Simmons and Torok-Storb 1991; Simmons and Torok-Storb 1991). The importance of standardizing the defining characteristics of MSCs was highlighted most recently by an excellent study, which identified a population of proliferative osteoblastic progenitors as MX-1 positive bone marrow stromal cells (Park, Spencer et al. 2012). This cell population could differentiate in vitro into osteolineage cells, adipocytes and chondrocytes, however, even in the setting of skeletal injury, this cell population is functionally restricted to an osteoblastic fate in vivo (Park, Spencer et al. 2012). In spite of this caveat in reviewing the role of MSCs in the HSC niche, numerous data suggest an important role of MSC in HSC support, both in murine models and in humans. Co-transplantation of MSCs with HSCs improves donor engraftment in non-human primates (Masuda, Ageyama et al. 2009) and enhances murine HSC self-renewal (Ahn, Park et al. 2010). Self-renewing human osteoprogenitor cells found in the marrow in close proximity to sinusoids can form supportive HSC niches (Sacchetti, Funari et al. 2007). In addition, ex vivo studies demonstrated that preparations of human mesenchymal stromal cells expanded cord blood mononuclear cells (McNiece, Harrington et al. 2004; Robinson, Ng et al. 2006). The same research group went on to recently demonstrate that transplantation of human cord-blood cells expanded with mesenchymal cells could be performed safely (de Lima, McNiece et al. 2012), and that MSC-expanded cord blood, in combination with unmanipulated human cord blood, significantly improved engraftment, accelerating time to platelet and neutrophil recovery after transplantation in adults (de Lima, McNiece et al. 2012). Relevant to this line of research, Pinho and colleagues recently showed that PDGFRα and CD51 expression define a bone marrow stromal cell population in both mice and humans that is highly enriched for MSCs and can support HSPC expansion in vitro (Pinho, Lacombe et al. 2013).

Recently, our group and others focused on a critical signal for HSC homing to the marrow, CXCL12, to define the MSC subset responsible for HSC support. CXCL12 (stromal-derived factor-1, SDF-1) is a chemokine that is constitutively expressed by several bone marrow stromal cell populations, and it is known to play an essential role in regulating HSC quiescence (Nie, Han et al. 2008; Tzeng, Li et al. 2011), repopulating activity (Tzeng, Li et al. 2011), and retention in the bone marrow (Kawabata, Ujikawa et al. 1999; Peled, Petit et al. 1999; Ara, Itoi et al. 2003; Bonig, Priestley et al. 2004). Recently, Dr. Sean Morrison's and our group independently assessed the impact of the conditional deletion of Cxcl12 from candidate niche cells on HSC maintenance (Ding and Morrison 2013; Greenbaum, Hsu et al. 2013). Deletion of Cxcl12 using osterix-Cre or leptin receptor-Cre transgenes resulted in constitutive HSPC mobilization, but HSC function was largely intact. Osterix-Cre efficiently mediates recombination in CXCL12-abundant reticular (CAR) cells, osteoblasts, and osteocytes (Greenbaum, Hsu et al. 2013). Interestingly, leptin receptor-Cre also targets the majority of CAR cells but does not mediate recombination in osteoblasts (Ding, Saunders et al. 2012). These observations have several important implications. First, although CAR cells (defined as bone marrow stromal cells with very high CXCL12 expression) are reported to have both adipogenic and osteogenic capacity in vitro, only a small subset of leptin receptor-negative CAR cells contribute to osteoblast development in vivo. Second, CXCL12 expression from CAR cells, while essential for efficient retention of HSPCs in the bone marrow, is not required for HSC maintenance.

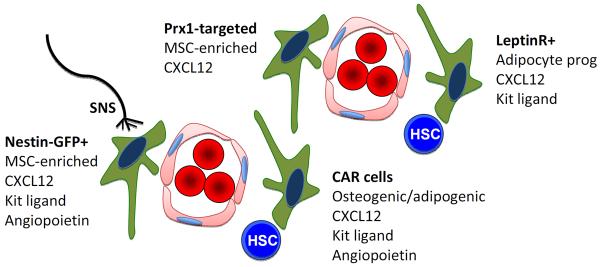

Both groups showed that deletion of Cxcl12 using Prx1-Cre resulted in a significant loss of HSCs, long-term repopulating activity, and HSC quiescence. Like Osterix-Cre, Prx1-Cre targets CAR cells and osteoblasts but also targets platelet derived growth factor receptor-alpha+ Sca+ (PaS) mesenchymal progenitors. A modest decrease in long-term repopulating activity (but not HSC quiescence) also was observed in mice with Cxcl12 deleted from endothelial cells. Thus, mesenchymal progenitors and, to a lesser extent, endothelial cells, contribute to HSC maintenance. A prior study identified bone marrow stromal cells that express GFP under control of Nestin regulatory sequences as a key component of the stem cell niche (Mendez-Ferrer, Michurina et al. 2010). These Nestin-GFP+ stromal cells are enriched for colony-forming-unit-fibroblast (CFU-F) activity and express high levels of HSC maintenance genes, including Kit ligand and CXCL12. Of note, Prx1-targeted PaS cells have a much higher CFU-F frequency (more than 10%) compared with Nestin-GFP+ stromal cells (less than 1%), suggesting that Prx1-Cre targeted PaS are more highly enriched for multipotent mesenchymal progenitors (Greenbaum, Hsu et al. 2013). Surprisingly, neither Prx1-Cre targeted PaS cells nor CAR cells express Nestin (Greenbaum, Hsu et al. 2013), and deletion of Cxcl12 or Kit ligand using Nestin-Cre does not affect HSCs (Ding, Saunders et al. 2012; Ding and Morrison 2013). A potential explanation for these disparate observations is the possibility that the Nestin-GFP transgene results in aberrant expression of GFP that does not accurately reflect Nestin expression. We suggest that Nestin-GFP+ may mark a stromal cell population that includes multipotent mesenchymal progenitors and CAR cells (similar to Prx1-Cre targeted cells).

Endothelial and perivascular cells

Endothelial structures give rise to the first definitive HSCs during embryonal development (Chen, Yokomizo et al. 2009). Data also suggest a crucial role of the endothelium in adult HSC regulation. Phenotypic HSCs, identified by their expression of signalling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM) markers, localize preferentially to endothelial structures (Wright, Wagers et al. 2001; Kiel, Yilmaz et al. 2005; Kiel, Yilmaz et al. 2008). This is not surprising, since it has been long known that HSCs circulate and are spontaneously mobilized (Storb, Graham et al. 1977; Wright, Wagers et al. 2001), and the vasculature is required for trafficking of HSCs between marrow and the bloodstream. Moreover, endothelial cells secrete factors which expand immature hematopoietic cells ex vivo, and support HSCs after myeloablation (Chute, Muramoto et al. 2006; Butler, Nolan et al. 2010; Kobayashi, Butler et al. 2010). Specifically, functional heterogeneity of the marrow microenvironment has been described, where both sinusoids and arterioles are present, and regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells is required for hematopoietic recovery from myeloablation (Hooper, Butler et al. 2009). The role of endothelial cells in HSC proliferation is further highlighted by data in Winkler et al, which demonstrate that the endothelial specific cell adhesion molecule E-selectin induces HSC to proliferate in vivo (Winkler, Barbier et al. 2012). Moreover, endothelial cells contribute to HSC maintenance, as Ding et demonstrated that deletion of the Kit ligand gene specifically in endothelial cells results in loss of HSC (Ding, Saunders et al. 2012). Together these data show that endothelial cells contribute to HSC maintenance and proliferation in vivo.

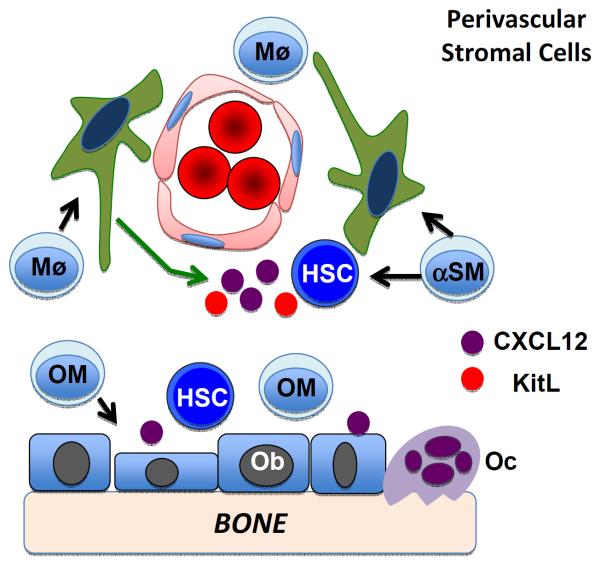

Since HSCs preferentially localize near BM sinusoids (Kiel, Yilmaz et al. 2005), perivascular stromal cells have also been proposed as a niche for HSCs. These cells produce high levels of soluble HSC-supportive factors (Sugiyama, Kohara et al. 2006; Sacchetti, Funari et al. 2007). Data are now suggesting that, as is the case with osteolineage cells, the perivascular stromal population is heterogeneous, and comprises other candidate HSC niche entities including some Nestin-GFP+ mesenchymal cells (Mendez-Ferrer, Michurina et al. 2010), CXCL-12 (SDF-1)-abundant reticular cells (CAR cells) (Sugiyama, Kohara et al. 2006), and Prx1-Cre targeted mesenchymal progenitors (Greenbaum, Hsu et al. 2013). Therefore, genetic models have been instrumental in the definition of this cell population and its role in HSC regulation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Perivascular stem cell niche.

The perivascular niche is comprised of endothelial cells and several, likely overlapping, mesenchymal stromal cell populations. These stromal cells provide key niche signals, such as CXCL12, kit ligand, and angiopoietin, that localize HSCs to the perivascular region and help maintain their quiescence and self-renewal capacity. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) regulate HSCs, at least in part, by targeting these perivascular stromal cells.

Another type of perivascular cell potentially involved in HSC regulation was identified as a critical source for Stem cell factor (SCF) or Kit Ligand, previously demonstrated to be required for HSC maintenance in its membrane-bound form (Barker 1994; Barker 1997). SCF was selectively deleted from hematopoietic, osteoblastic, Nestin-GFP-expressing stromal, endothelial or Leptin receptor (Lepr)-expressing perivascular stromal cell types (Ding, Saunders et al. 2012). Notably, HSC frequency and function were only impaired by the absence of SCF from Tie2+ endothelial and Lepr+ perivascular cells. These perivascular, Scf-expressing stromal cells lack Nestin expression but expressed high levels of Cxcl12, alkaline phosphatase, Vcam1, Pdgfra and Pdgfrb when compared to whole bone marrow cell preparations, confirming their mesenchymal and stromal cell composition, and implicating niche-derived SCF requirement from Lepr+ perivascular cells as necessary for HSC maintenance in adult BM.

Neuronal and glial cells

Both neuronal as well as glial cells have been implicated in the modulation of HSC fates. Convincing data have suggested that G-CSF-mediated HSC mobilization is at least in part regulated by sympathetic nervous system (SNS) neurons (Katayama, Battista et al. 2006). SNS neurons coordinate the circadian oscillation of HSC numbers in the marrow and their mobilization to the bloodstream by regulating local production of CXCL12, as demonstrated by experiments in which ablation of SNS neurons resulted in loss of circadian controlled HSCs mobilization into the periphery (Mendez-Ferrer, Lucas et al. 2008). In addition, sympathectomy of one tibia in a mouse resulted in altered expression of CXCL12, while the sham operated contralateral tibia was unaffected (Mendez-Ferrer, Lucas et al. 2008).

An unexpected contribution of glial cells in HSC fate determination was discovered by examining the marrow source for transforming growth factor β (TGF-β). TGFβ had previously been demonstrated to induce HSC quiescence ex vivo (Yamazaki, Iwama et al. 2009). While multiple marrow cells are potential sources of inactive TGFβ, nonmyelinating Schwann cells are the major source of activated TGF-β in the bone marrow (Yamazaki, Ema et al. 2011). These glial cells are closely associated with HSCs, and produce numerous factors previously identified as playing a role in the HSC niche (Yamazaki, Ema et al. 2011). Ablation of this population in the bone marrow results in a loss of HSC dormancy and ultimately of HSC numbers (Barker 1997). Therefore, neuronal cells and glia have been recently implicated in HSC regulation in the bone marrow.

Adipocytes

Adipocytic cells represent a large portion of the adult marrow, especially in humans. In particular, an increase in the adipocytic marrow component has been associated with aging (Kirkland, Tchkonia et al. 2002; Rosen, Ackert-Bicknell et al. 2009), while it has been well established that the functional capacity of the hematopoietic system decreases with aging (Berkahn and Keating 2004). Moreover, age dependent changes have been demonstrated in both murine and human HSCs (Van Zant and Liang 2012), some of which could be induced by the microenvironment. In spite of these findings, initially adipocytes were considered as potentially supportive of HSCs. For example, the adipokine adiponectin is secreted by adipocyte, and its receptors are expressed by HSCs (DiMascio, Voermans et al. 2007). This adipocytic product has been demonstrated to increase proliferation of HSCs while retaining their repopulating potential (DiMascio, Voermans et al. 2007). Adiponectin however, is not solely produced by adipocytes in the marrow, but is also expressed by osteolineage cells (Berner, Lyngstadaas et al. 2004).

In contrast to these potentially beneficial effects of adipocytes on HSCs, adipocyte numbers have more recently been described as inversely related to numbers of HSCs in the marrow by comparing anatomically distinct regions of the skeleton that display varying levels of adiposity (Naveiras, Nardi et al. 2009). Additional studies demonstrated that loss of adipocytes in the marrow, either genetically or pharmacologically, resulted in enhanced engraftment of HSCs and improved hematopoietic recovery following myeloablative injury (Naveiras, Nardi et al. 2009). Therefore, a dominant inhibitory effect of adipocytes on HSCs has recently been postulated.

Hematopoietic HSC niche components

There is accumulating evidence that hematopoietic cells generate signals that indirectly modulate HSC function through regulation of stromal cells that comprise the stem cell niche. In this section, we review recent data implicating osteoclasts, macrophages/monocytes, and neutrophils in the regulation of the stem cell niche.

Osteoclasts

Osteoclasts, by virtue of their close association with osteoblasts and proximity to the endosteal niche, have received considerable attention as a hematopoietic cell type that may modulate the stem cell niche. Genetic and pharmacologic approaches to modulate osteoclast function suggest that osteoclasts positively regulate HSCs. Inhibition of osteoclast activity by treatment with bisphosphonates is associated with a modest (1.5-fold) decrease in phenotypic HSCs (Flk2- lineage- Sca+ Kit+ cells) and a corresponding decrease in long-term repopulating activity (Lymperi, Ersek et al. 2011). A much more severe loss of HSCs is present in in the bone marrow of oc/oc mice, which carry mutations of Tirg encoding for the a3 subunit of the vacuolar type ATPase complex. The Tirg mutations in oc/oc mice are associated with severe osteopetrosis due to impaired acidification and bone resorption at the ruffle border interface between osteoclasts and bone. Strikingly, there is a near complete absence of phenotypic HSCs (lineage- Sca+ Kit+ cells) in the bone marrow of oc/oc mice (Mansour, Abou-Ezzi et al. 2012).

The mechanisms by which osteoclasts regulate HSCs are largely unknown. In oc/oc mice, the severe loss of bone marrow medullary space secondary to osteopetrosis likely contributes to the loss of HSCs. However, Mansour et al also reported a marked expansion of phenotypic mesenchymal progenitors (PDGFRα+ Sca+ lineage− cells) but a relative decrease in mature osteoblasts in oc/oc mice, raising the possibility that osteoclasts indirectly regulate HSCs by altering the stem cell niche (Mansour, Abou-Ezzi et al. 2012). Finally, osteoclasts may regulate HSC function through degradation of bone matrix, which results in the release of calcium ions and certain cytokines, such as TGFβ, which can regulate HSC function (Yamazaki, Ema et al. 2011) (Adams, Chabner et al. 2006).

Several studies have examined the contribution of osteoclasts to HSC mobilization by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). G-CSF treatment is associated with the mobilization of HSCs from the bone marrow to blood, and it is commonly used in the clinical setting to obtain sufficient donor HSCs from the blood for stem cell transplantation. Prior studies have established that G-CSF induces HSC mobilization primarily by suppressing osteoblasts and CXCL12 expression from bone marrow stromal cells (Petit, Szyper-Kravitz et al. 2002; Levesque, Hendy et al. 2003; Semerad, Christopher et al. 2005; Christopher, Liu et al. 2009). Thus, G-CSF induced HSC mobilization represents a useful tool to perturb and study the stem cell niche. Kollet and colleagues reported that activation of osteoclasts by injection of RANK ligand (RANKL) was associated with moderate HSPC mobilization (Kollet, Dar et al. 2006). Conversely, inhibition of osteoclasts, either genetically by knocking out PTPε or by injecting mice with calcitonin, blunts the mobilization response to G-CSF. The authors suggested that osteoclasts induce HSPC mobilization by release of the proteinase cathepsin K, which can, at least in vitro, cleave CXCL12. On the other hand, Miyamoto and colleagues showed using three different transgenic mouse models with impaired osteoclast activity (CSF-1, c-fos, or RANKL deficient mice) that HSPC mobilization, at baseline or after G-CSF treatment, is increased (Miyamoto, Yoshida et al. 2011). Consistent with this finding, several groups have reported increased osteoblast suppression and HSPC mobilization by G-CSF after bisphosphonate treatment (Winkler, Sims et al. 2010; Miyamoto, Yoshida et al. 2011). Thus, the preponderance of current evidence suggests that osteoclasts negatively regulate HSPC trafficking from the bone marrow but are dispensable for G-CSF induced HSPC mobilization.

Macrophages

There is considerable phenotypic, functional, and developmental heterogeneity in tissue macrophages (Yona, Kim et al. 2013). This extends to the bone marrow where several macrophages populations have been identified. Chang et al described an F480+ population of macrophages that are closely associated with osteoblasts and bone lining cells on endosteal and periosteal surfaces. Indeed, these cells, termed osteomacs, have been shown to form a canopy over mature osteoblasts at sites of bone formation under steady state conditions (Chang, Raggatt et al. 2008) or after bone injury (Alexander, Chang et al. 2011). Chow et al described a CD169+ population of macrophages (also F480+) that is associated with perivascular Nestin-GFP+ stromal cells (Chow, Lucas et al. 2011). Whether osteomacs and CD169+ macrophages represent distinct cell populations is unclear. Recently, Ludin et al reported the identification of a rare macrophage subset (representing less than 0.1% of total bone marrow cells) with high expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Ludin, Itkin et al. 2012). These cells express high levels of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and may regulate HSC function through localized production of PGE2 (Ludin, Itkin et al. 2012). This population is also likely targeted by pharmacologic in vivo treatment with dmPGE2, which ameliorates sublethal irradiation-induced damage to the HSC pool by inhibiting apoptosis while preserving long term function (Porter, Georger et al. 2013). dmPGE2-mediated enhancement of hematopoietic recovery is likely to occur both through direct effects on HSPCs as well as changes to the microenvironment, where COX2 activity is increased and αSMA+ macrophages are increased. In addition to macrophages, the bone marrow is a rich reservoir of other monocyte-lineage cells, including monocytes and myeloid dendritic cells.

There is accumulating evidence that macrophages in the bone play an essential role in regulating the stem cell niche and HSC function. In cultures of primary bone marrow stromal cells, the presence of macrophages significantly enhances the production of mature osteoblasts (Chang, Raggatt et al. 2008). Several experimental approaches have been employed to ablate monocytes/macrophages in vivo. MAFIA mice express a suicide fusion gene comprised of a FK506 binding domain and the cytoplasmic domain of Fas expressed under control of the c-fms promoter. Treatment of MAFIA mice with a chemical dimerizer induces Fas-mediated apoptosis in monocytes and macrophages. Ablation of monocytes/macrophages in this model is very efficient and is associated with marked suppression of osteoblasts (Chang, Raggatt et al. 2008) and HSPC mobilization into the blood (Winkler, Sims et al. 2010). Of note, macrophage ablation using the MAFIA mouse model is associated with considerable systemic inflammation, potentially indirectly contributing to HSPC mobilization. Treatment of mice with clodronate-loaded liposomes results in a more modest reduction in bone marrow monocytes/macrophages (80–90% reduction) and is not associated with obvious signs of systemic inflammation (Winkler, Sims et al. 2010; Chow, Lucas et al. 2011). Although the magnitude is reduced compared with MAFIA mice, monocyte-macrophage ablation with clodronate-loaded liposomes resulted in HSPC mobilization, osteoblast loss, and decreased expression of stem cell niche genes, including CXCL12, Kit ligand, and angiopoietin-1 (Winkler, Sims et al. 2010; Chow, Lucas et al. 2011). To further define the monocytic lineage cell population in the bone marrow that contributes to stem cell niche maintenance, Chow et al ablated CD169+ macrophages using transgenic mice that express the diphtheria toxin receptor under control of CD169 regulatory elements (Winkler, Sims et al. 2010; Chow, Lucas et al. 2011). They showed that ablation of CD169+ macrophages was associated with modest HSPC mobilization and decreased expression of CXCL12, Kit ligand, and angiopoietin-1 from Nestin-GFP+ bone marrow stromal cells. Interestingly, this same group recently showed that CD169+ macrophages play a key role in supporting erythropoiesis in the bone marrow (Chow, Huggins et al. 2013). Consistent with these findings, Westerterp et al recently showed that deletion of the ATP binding cassette transporters ABCA1 and ABCG1 in macrophages and/or myeloid dendritic cells resulted in a loss of osteomacs and CD169+ macrophages in the bone marrow and was associated with modest HSPC mobilization and suppression of CXCL12 expression (Westerterp, Gourion-Arsiquaud et al. 2012).

Studies of G-CSF receptor deficient bone marrow chimeras established that G-CSF signaling in bone marrow stromal cells is not required for G-CSF induced stem cell niche suppression of HSPC mobilization (Liu, Poursine-Laurent et al. 2000). To evaluate the role of monocytic cells in G-CSF-induced HSPC mobilization, we generated transgenic mice in which expression of the G-CSFR is restricted to CD68+ monocytes and macrophages (Christopher, Rao et al. 2011). Treatment of these mice with G-CSF induces marked suppression of osteoblasts and CXCL12 expression and is associated with robust HSPC mobilization. Importantly, G-CSF treatment results in a marked loss of monocytes (Christopher, Rao et al. 2011) and osteomacs (Winkler, Sims et al. 2010) from the bone marrow.

Neutrophils

Previous studies suggested that neutrophils may contribute to G-CSF-induced HSPC mobilization by the release of specific proteinases, such as MMP9, cathepsin G, and neutrophil elastase, that degrade key stem cell niche molecules, including CXCL12 (Levesque, Takamatsu et al. 2001; Heissig, Hattori et al. 2002). However, we showed that G-CSF induced HSPC mobilization is normal in mice lacking these proteinases (Levesque, Liu et al. 2004). Moreover, we and others showed that G-CSF primarily suppresses CXCL12 at the transcriptional level (Petit, Szyper-Kravitz et al. 2002; Levesque, Hendy et al. 2003; Semerad, Christopher et al. 2005). Thus, the role of neutrophil proteinases in disrupting the stem cell niche during G-CSF treatment is questionable. As noted above, studies of CD68:G-CSF receptor transgenic mice show that G-CSF signaling in monocytic cells is sufficient to induce robust HPSC mobilization and CXCl12 suppression (Christopher, Rao et al. 2011). Moreover, these mice are severely neutropenic (due to the lack of G-CSF receptor expression on neutrophil lineage cells), suggesting that neutrophils are not required for G-CSF-induced HPSC mobilization. On the other hand, Singh et al recently reported that neutrophil depletion using an anti-LyG antibody modestly attenuated G-CSF-induced HSPC mobilization and osteoblast suppression. Together, these data suggest that neutrophils, while not required, may play a minor role to augment HSPC mobilization by G-CSF (Singh, Hu et al. 2012).

Model

Together, these data support a model in which monocytes/macrophages in the bone marrow provide signal(s) that are required for maintenance of stromal cells that comprise the stem cell niche (Figure 2). Specifically, monocytes/macrophages support osteoblast function and the expression of key stem cell niche genes, including CXCL12 and Kit ligand, from Nestin-GFP+ perivascular stromal cells. Although CD169+ macrophages clearly contribute to stem cell niche maintenance, ablation of these cells results in only modest HSPC mobilization and CXCl12 suppression (compared with MAFIA mice or CD68:G-CSF receptor mice). Thus, other monocyte/macrophage cell populations in the bone marrow also likely contribute to niche maintenance. Indeed, our preliminary data suggest that myeloid dendritic cells also generate signals that support CXCL12 production from bone marrow stromal cells (unpublished observations). G-CSF disrupts the stem cell niche and induces HPSC mobilization primarily by targeting monocytes/macrophages. In addition to resulting in a loss of monocytes/macrophages in the bone marrow, G-CSF suppresses the production of inflammatory cytokines from monocytes/macrophages, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) (Boneberg, Hareng et al. 2000). The signals generated by macrophages/monocytes that support stromal cells comprising the stem cell niche are currently unknown.

Figure 2. Macrophage regulation of HSCs.

Osteomacs (OM) and CD169+ macrophages (Mø) provide signals that contribute to osteoblast (Ob) maintenance and CXCL12 and kit ligand (Scf) expression from perivascular Nestin-GFP+ stromal cells. Recently, α-smooth muscle actin+ macrophages (αSM) have been identified that may regulate HSCs through local production of PGE2. Osteoclasts (Oc) negatively regulate HSCs through unknown mechanisms.

Physiologic regulation of the niche

So far we have highlighted different cellular components of the niche and their ability to support HSCs. However, these cell populations can also be influenced by physiologic stimuli, such as sympathetic innervation (Katayama, Battista et al. 2006), circadian rhythms (Mendez-Ferrer, Lucas et al. 2008) and hormonal signals (Calvi, Adams et al. 2003), which further add to the complexity of the niche. A localized physiologic modulator of the HSC niche of particular interest is hypoxia. Data suggest that hypoxia affects both niche cells as well as directly HSCs to consistently increase HSC quiescence. Data support a crucial role of hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) in bone development and turnover -as demonstrated by genetic deletion of Hif1a gene in osteoblasts affects bone formation (Wang, Wan et al. 2007). Stabilization of HIF in osteolineage cells expands HSCs, suggesting that hypoxic osteolineage cells are likely more supportive of HSC (Rankin, Wu et al. 2012). On the other hand, deletion of the Hif1a gene promotes HSC exit from G0 and sensitizes HSCs to repetitive cycles of myelosuppression, while pharmacological stabilization of HIF-1a protein increases HSC quiescence, demonstrating that HIF1a is a critical regulator of HSC quiescence (Takubo, Goda et al. 2010; Forristal, Winkler et al. 2013). Prior studies had suggested that HSPCs with the ability to serially reconstitute are located in the endosteal region of the bone marrow, which is characterized by low perfusion and relative hypoxia (Levesque, Winkler et al. 2007; Winkler, Barbier et al. 2010). However, a recent study showed that the endosteal region is well vascularized (Nombela-Arrieta, Pivarnik et al. 2013). Moreover, the majority of HSPCs in the endosteal region are perivascular. Thus, HSPCs in the endosteal region are likely to be relatively well oxygenated. A potential explanation for this discrepancy is the observation that HSPCs display a hypoxic profile (defined by strong retention of pimonidazole and expression of HIF-1α) regardless of their location in the bone marrow (Nombela-Arrieta, Pivarnik et al. 2013). Indeed, even HSPCs in the peripheral circulation display a hypoxic profile. Thus, intrinsic differences in metabolism rather than localization to a hypoxic microenvironment may define the hypoxic profile of HSCs.

Summary

Since the initial proposal of the niche hypothesis, there has been considerable progress in defining the cellular components that comprise the stem cell niche in the bone marrow. Current studies highlight the heterogeneity of the niche, with specific stromal cell populations producing signals that regulate specific aspects of HSC biology, such as quiescence and retention in the bone marrow. Mature hematopoietic cells, in particular macrophages, also contribute to HSC maintenance through regulation of stromal cells and possibly through direct effects on HSCs. The complexity of the stem niche allows for flexibility in HSC responses to environmental cues such as inflammation and provides a mechanism to tightly couple HSCs with bone metabolism. It also provides multiple potential therapeutic targets for manipulation to modulate HSC and their progeny. Indeed, by understanding the cellular and molecular components of the stem cell niche, we may one day be able to simply and safely manipulate HSCs in vivo on demand. Moreover, since the stem cell niche may provide signals that support certain malignancies, drugs that target the niche hold promise as a way to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. B.J. Frisch for review of the manuscript and members of the Calvi and Link laboratories for helpful discussions. This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIDDK grants DK076876 and DK081843 to LMC, and HL60772 to DCL).

Footnotes

The authors have stated that they have no conflict of interest.

DISCLOSURES: NONE.

Referenced Literature

- Adams GB, Chabner KT, et al. Stem cell engraftment at the endosteal niche is specified by the calcium-sensing receptor. Nature. 2006;439(7076):599–603. doi: 10.1038/nature04247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams GB, Martin RP, et al. Therapeutic targeting of a stem cell niche (vol 25, pg 238, 2007) Nature Biotechnology. 2007;25(8):944–944. doi: 10.1038/nbt1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn JY, Park G, et al. Intramarrow injection of beta-catenin-activated, but not naive mesenchymal stromal cells stimulates self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells in bone marrow. Exp Mol Med. 2010;42(2):122–131. doi: 10.3858/emm.2010.42.2.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KA, Chang MK, et al. Osteal macrophages promote in vivo intramembranous bone healing in a mouse tibial injury model. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(7):1517–1532. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ara T, Itoi M, et al. A role of CXC chemokine ligand 12/stromal cell-derived factor-1/pre-B cell growth stimulating factor and its receptor CXCR4 in fetal and adult T cell development in vivo. J Immunol. 2003;170(9):4649–4655. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai F, Hirao A, et al. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2004;118(2):149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballen KK, Shpall EJ, et al. Phase I trial of parathyroid hormone to facilitate stem cell mobilization. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(7):838–843. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JE. Sl/Sld hematopoietic progenitors are deficient in situ. Exp Hematol. 1994;22(2):174–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker JE. Early transplantation to a normal microenvironment prevents the development of Steel hematopoietic stem cell defects. Exp Hematol. 1997;25(6):542–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi B, Li JY, et al. Silencing of parathyroid hormone (PTH) receptor 1 in T cells blunts the bone anabolic activity of PTH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(12):E725–733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120735109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkahn L, Keating A. Hematopoiesis in the elderly. Hematology. 2004;9(3):159–163. doi: 10.1080/10245330410001701468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berner HS, Lyngstadaas SP, et al. Adiponectin and its receptors are expressed in bone-forming cells. Bone. 2004;35(4):842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco P, Robey PG, et al. ”Mesenchymal” stem cells in human bone marrow (skeletal stem cells): a critical discussion of their nature, identity, and significance in incurable skeletal disease. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21(9):1057–1066. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boneberg EM, Hareng L, et al. Human monocytes express functional receptors for granulocyte colony-stimulating factor that mediate suppression of monokines and interferon-gamma. Blood. 2000;95(1):270–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonig H, Priestley GV, et al. PTX-sensitive signals in bone marrow homing of fetal and adult hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;104(8):2299–2306. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg O, Frisch BJ, et al. Osteoblastic N-cadherin is not required for microenvironmental support and regulation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 2012;120(2):303–313. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner S, Theiss HD, et al. Primary hyperparathyroidism is associated with increased circulating bone marrow-derived progenitor cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293(6):E1670–1675. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00287.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JM, Nolan DJ, et al. Endothelial cells are essential for the self-renewal and repopulation of Notch-dependent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(3):251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi LM, Adams GB, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425(6960):841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi LM, Bromberg O, et al. Osteoblastic expansion induced by parathyroid hormone receptor signaling in murine osteocytes is not sufficient to increase hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2012;119(11):2489–2499. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-360933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvi LM, Sims NA, et al. Activated parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone-related protein receptor in osteoblastic cells differentially affects cortical and trabecular bone. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(3):277–286. doi: 10.1172/JCI11296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantor AB, Orkin SH. Hematopoietic development: a balancing act. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11(5):513–519. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MK, Raggatt LJ, et al. Osteal tissue macrophages are intercalated throughout human and mouse bone lining tissues and regulate osteoblast function in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181(2):1232–1244. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MJ, Yokomizo T, et al. Runx1 is required for the endothelial to haematopoietic cell transition but not thereafter. Nature. 2009;457(7231):887–891. doi: 10.1038/nature07619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YH, Chitteti BR, et al. Impact of maturational status on the ability of osteoblasts to enhance the hematopoietic function of stem and progenitor cells. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(5):1111–1121. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitteti BR, Cheng YH, et al. Impact of interactions of cellular components of the bone marrow microenvironment on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell function. Blood. 2010;115(16):3239–3248. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-246173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitteti BR, Cheng YH, et al. Osteoblast lineage cells expressing high levels of Runx2 enhance hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation and function. J Cell Biochem. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jcb.22694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitteti BR, Cheng YH, et al. Osteoblast lineage cells expressing high levels of Runx2 enhance hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation and function. J Cell Biochem. 2010;111(2):284–294. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow A, Huggins M, et al. CD169(+) macrophages provide a niche promoting erythropoiesis under homeostasis and stress. Nat Med. 2013;19(4):429–436. doi: 10.1038/nm.3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow A, Lucas D, et al. Bone marrow CD169+ macrophages promote the retention of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in the mesenchymal stem cell niche. J Exp Med. 2011;208(2):261–271. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher MJ, Liu F, et al. Suppression of CXCL12 production by bone marrow osteoblasts is a common and critical pathway for cytokine-induced mobilization. Blood. 2009;114(7):1331–1339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher MJ, Rao M, et al. Expression of the G-CSF receptor in monocytic cells is sufficient to mediate hematopoietic progenitor mobilization by G-CSF in mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208(2):251–260. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chute JP, Muramoto GG, et al. Molecular profile and partial functional analysis of novel endothelial cell-derived growth factors that regulate hematopoiesis. Stem Cells. 2006;24(5):1315–1327. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colmone A, Amorim M, et al. Leukemic cells create bone marrow niches that disrupt the behavior of normal hematopoietic progenitor cells. Science. 2008;322(5909):1861–1865. doi: 10.1126/science.1164390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lima M, McNiece I, et al. Cord-blood engraftment with ex vivo mesenchymal-cell coculture. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(24):2305–2315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMascio L, Voermans C, et al. Identification of adiponectin as a novel hemopoietic stem cell growth factor. J Immunol. 2007;178(6):3511–3520. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Morrison SJ. Haematopoietic stem cells and early lymphoid progenitors occupy distinct bone marrow niches. Nature. 2013;495(7440):231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature11885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding L, Saunders TL, et al. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2012;481(7382):457–462. doi: 10.1038/nature10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici M, Rasini V, et al. Restoration and reversible expansion of the osteoblastic hematopoietic stem cell niche after marrow radioablation. Blood. 2009;114(11):2333–2343. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzierzak E. Embryonic beginnings of definitive hematopoietic stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;872:256–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08470.x. discussion 262–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzierzak E, Speck NA. Of lineage and legacy: the development of mammalian hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(2):129–136. doi: 10.1038/ni1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enver T, Pera M, et al. Stem cell states, fates, and the rules of attraction. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(5):387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazeli PK, Horowitz MC, et al. Marrow fat and bone--new perspectives. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):935–945. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliedner MC. Research within the field of blood and marrow transplantation nursing: how can it contribute to higher quality of care? Int J Hematol. 2002;76(Suppl 2):289–291. doi: 10.1007/BF03165135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forristal CE, Winkler IG, et al. Pharmacologic stabilization of HIF-1alpha increases hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in vivo and accelerates blood recovery after severe irradiation. Blood. 2013;121(5):759–769. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-408419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch BJ, Ashton JM, et al. Functional inhibition of osteoblastic cells in an in vivo mouse model of myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;119(2):540–550. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch BJ, Porter RL, et al. In vivo prostaglandin E(2) treatment alters the bone marrow microenvironment and preferentially expands short-term hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2009;114(19):4054–4063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-205823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E, Tumbar T, et al. Socializing with the neighbors: stem cells and their niche. Cell. 2004;116(6):769–778. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulciniti M, Tassone P, et al. Anti-DKK1 mAb (BHQ880) as a potential therapeutic agent for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2009;114(2):371–379. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-191577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goessling W, Allen RS, et al. Prostaglandin E2 enhances human cord blood stem cell xenotransplants and shows long-term safety in preclinical nonhuman primate transplant models. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8(4):445–458. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goltzman D. Studies on the mechanisms of the skeletal anabolic action of endogenous and exogenous parathyroid hormone. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2008;473(2):218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong JK. Endosteal marrow: a rich source of hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1978;199(4336):1443–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.75570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf T, Enver T. Forcing cells to change lineages. Nature. 2009;462(7273):587–594. doi: 10.1038/nature08533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum A, Hsu YM, et al. CXCL12 in early mesenchymal progenitors is required for haematopoietic stem-cell maintenance. Nature. 2013;495(7440):227–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum AM, Revollo LD, et al. N-cadherin in osteolineage cells is not required for maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2012;120(2):295–302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein V. Blood cells and blood cell development in the animal kingdom. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:677–712. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haylock DN, Williams B, et al. Hemopoietic stem cells with higher hemopoietic potential reside at the bone marrow endosteum. Stem Cells. 2007;25(4):1062–1069. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heissig B, Hattori K, et al. Recruitment of stem and progenitor cells from the bone marrow niche requires MMP-9 mediated release of kit-ligand. Cell. 2002;109(5):625–637. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00754-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper AT, Butler JM, et al. Engraftment and reconstitution of hematopoiesis is dependent on VEGFR2-mediated regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(3):263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa K, Arai F, et al. Cadherin-based adhesion is a potential target for niche manipulation to protect hematopoietic stem cells in adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(3):194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa K, Arai F, et al. Knockdown of N-cadherin suppresses the long-term engraftment of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2010;116(4):554–563. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-224857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y, Wang J, et al. Annexin II expressed by osteoblasts and endothelial cells regulates stem cell adhesion, homing, and engraftment following transplantation. Blood. 2007;110(1):82–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai T, Spradling A. An empty Drosophila stem cell niche reactivates the proliferation of ectopic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(8):4633–4638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830856100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama Y, Battista M, et al. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124(2):407–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata K, Ujikawa M, et al. A cell-autonomous requirement for CXCR4 in long-term lymphoid and myeloid reconstitution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(10):5663–5667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, et al. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121(7):1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, et al. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121(7):1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, et al. CD150- cells are transiently reconstituting multipotent progenitors with little or no stem cell activity. Blood. 2008;111(8):4413–4414. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-129601. author reply 4414–4415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T, et al. Adipogenesis and aging: does aging make fat go MAD? Exp Gerontol. 2002;37(6):757–767. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi H, Butler JM, et al. Angiocrine factors from Akt-activated endothelial cells balance self-renewal and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(11):1046–1056. doi: 10.1038/ncb2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollet O, Dar A, et al. Osteoclasts degrade endosteal components and promote mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Nat Med. 2006;12(6):657–664. doi: 10.1038/nm1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapid K, Itkin T, et al. GSK3beta regulates physiological migration of stem/progenitor cells via cytoskeletal rearrangement. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(4):1705–1717. doi: 10.1172/JCI64149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque JP. N(o)-cadherin role for HSCs. Blood. 2012;120(2):237–238. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-431148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque JP, Hendy J, et al. Disruption of the CXCR4/CXCL12 chemotactic interaction during hematopoietic stem cell mobilization induced by GCSF or cyclophosphamide.g. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(2):187–196. doi: 10.1172/JCI15994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque JP, Liu F, et al. Characterization of hematopoietic progenitor mobilization in protease-deficient mice. Blood. 2004;104(1):65–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque JP, Takamatsu Y, et al. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD106) is cleaved by neutrophil proteases in the bone marrow following hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 2001;98(5):1289–1297. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque JP, Winkler IG, et al. Hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization results in hypoxia with increased hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-1 alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor A in bone marrow. Stem Cells. 2007;25(8):1954–1965. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Adams J, et al. PTH expands short-term murine hemopoietic stem cells through T cells. Blood. 2012;120(22):4352–4362. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-438531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Poursine-Laurent J, et al. Expression of the G-CSF receptor on hematopoietic progenitor cells is not required for their mobilization by G-CSF. Blood. 2000;95(10):3025–3031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Celso C, Fleming HE, et al. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature. 2009;457(7225):92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature07434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord BI, Testa NG, et al. The relative spatial distributions of CFUs and CFUc in the normal mouse femur. Blood. 1975;46(1):65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losick VP, Morris LX, et al. Drosophila stem cell niches: a decade of discovery suggests a unified view of stem cell regulation. Dev Cell. 2011;21(1):159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludin A, Itkin T, et al. Monocytes-macrophages that express alpha-smooth muscle actin preserve primitive hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(11):1072–1082. doi: 10.1038/ni.2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lymperi S, Ersek A, et al. Inhibition of osteoclast function reduces hematopoietic stem cell numbers in vivo. Blood. 2011;117(5):1540–1549. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lymperi S, Horwood N, et al. Strontium can increase some osteoblasts without increasing hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2008;111(3):1173–1181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YD, Park C, et al. Defects in osteoblast function but no changes in long-term repopulating potential of hematopoietic stem cells in a mouse chronic inflammatory arthritis model. Blood. 2009;114(20):4402–4410. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Abou-Ezzi G, et al. Osteoclasts promote the formation of hematopoietic stem cell niches in the bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2012;209(3):537–549. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusic A, Kalinowski JF, et al. Production of leukemia inhibitory factor mRNA and protein by malignant and immortalized bone cells. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8(5):617–624. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda S, Ageyama N, et al. Cotransplantation with MSCs improves engraftment of HSCs after autologous intra-bone marrow transplantation in nonhuman primates. Exp Hematol. 2009;37(10):1250–1257. e1251. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNiece I, Harrington J, et al. Ex vivo expansion of cord blood mononuclear cells on mesenchymal stem cells. Cytotherapy. 2004;6(4):311–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240410004871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvinsky A, Dzierzak E. Definitive hematopoiesis is autonomously initiated by the AGM region. Cell. 1996;86(6):897–906. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452(7186):442–447. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Ferrer S, Michurina TV, et al. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466(7308):829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto K, Yoshida S, et al. Osteoclasts are dispensable for hematopoietic stem cell maintenance and mobilization. J Exp Med. 2011;208(11):2175–2181. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Arai F, et al. Isolation and characterization of endosteal niche cell populations that regulate hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2010;116(9):1422–1432. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Arai F, et al. Isolation and characterization of endosteal niche cell populations that regulate hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naveiras O, Nardi V, et al. Bone-marrow adipocytes as negative regulators of the haematopoietic microenvironment. Nature. 2009;460(7252):259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature08099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Y, Han YC, et al. CXCR4 is required for the quiescence of primitive hematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205(4):777–783. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson SK, Dooner MS, et al. Potential and distribution of transplanted hematopoietic stem cells in a nonablated mouse model. Blood. 1997;89(11):4013–4020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson SK, Johnston HM, et al. Spatial localization of transplanted hemopoietic stem cells: inferences for the localization of stem cell niches. Blood. 2001;97(8):2293–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nombela-Arrieta C, Pivarnik G, et al. Quantitative imaging of haematopoietic stem and progenitor cell localization and hypoxic status in the bone marrow microenvironment. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(5):533–543. doi: 10.1038/ncb2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North TE, Goessling W, et al. Prostaglandin E2 regulates vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell homeostasis. Nature. 2007;447(7147):1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/nature05883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osawa M, Hanada K, et al. Long-term lymphohematopoietic reconstitution by a single CD34-low/negative hematopoietic stem cell. Science. 1996;273(5272):242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Spencer JA, et al. Endogenous bone marrow MSCs are dynamic, fate-restricted participants in bone maintenance and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(3):259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled A, Petit I, et al. Dependence of human stem cell engraftment and repopulation of NOD/SCID mice on CXCR4. Science. 1999;283(5403):845–848. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit I, Szyper-Kravitz M, et al. G-CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF-1 and up-regulating CXCR4.[erratum appears in Nat Immunol 2002 Aug;3(8):787] Nature Immunology. 2002;3(7):687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinho S, Lacombe J, et al. PDGFRalpha and CD51 mark human Nestin+ sphere-forming mesenchymal stem cells capable of hematopoietic progenitor cell expansion. J Exp Med. 2013 doi: 10.1084/jem.20122252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter RL, Georger MA, et al. Prostaglandin E2 increases hematopoietic stem cell survival and accelerates hematopoietic recovery after radiation injury. Stem Cells. 2013;31(2):372–383. doi: 10.1002/stem.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian H, Buza-Vidas N, et al. Critical role of thrombopoietin in maintaining adult quiescent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(6):671–684. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiang YW, Chen Y, et al. Myeloma-derived Dickkopf-1 disrupts Wnt-regulated osteoprotegerin and RANKL production by osteoblasts: a potential mechanism underlying osteolytic bone lesions in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;112(1):196–207. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin EB, Wu C, et al. The HIF signaling pathway in osteoblasts directly modulates erythropoiesis through the production of EPO. Cell. 2012;149(1):63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SN, Ng J, et al. Superior ex vivo cord blood expansion following co-culture with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37(4):359–366. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen CJ, Ackert-Bicknell C, et al. Marrow fat and the bone microenvironment: developmental, functional, and pathological implications. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2009;19(2):109–124. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v19.i2.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacchetti B, Funari A, et al. Self-renewing osteoprogenitors in bone marrow sinusoids can organize a hematopoietic microenvironment. Cell. 2007;131(2):324–336. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepers K, Hsiao EC, et al. Activated Gs signaling in osteoblastic cells alters the hematopoietic stem cell niche in mice. Blood. 2012;120(17):3425–3435. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-395418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells. 1978;4(1–2):7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semerad CL, Christopher MJ, et al. G-CSF potently inhibits osteoblast activity and CXCL12 mRNA expression in the bone marrow. Blood. 2005;106(9):3020–3027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiozawa Y, Pedersen EA, et al. Human prostate cancer metastases target the hematopoietic stem cell niche to establish footholds in mouse bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(4):1298–1312. doi: 10.1172/JCI43414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons PJ, Torok-Storb B. CD34 expression by stromal precursors in normal human adult bone marrow. Blood. 1991;78(11):2848–2853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons PJ, Torok-Storb B. Identification of stromal cell precursors in human bone marrow by a novel monoclonal antibody, STRO-1. Blood. 1991;78(1):55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Hu P, et al. Expansion of bone marrow neutrophils following G-CSF administration in mice results in osteolineage cell apoptosis and mobilization of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Leukemia. 2012;26(11):2375–2383. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Zhu, et al. Germline stem cells anchored by adherens junctions in the Drosophila ovary niches. Science. 2002;296(5574):1855–1857. doi: 10.1126/science.1069871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storb R, Graham TC, et al. Demonstration of hemopoietic stem cells in the peripheral blood of baboons by cross circulation. Blood. 1977;50(3):537–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimura R, He XC, et al. Noncanonical wnt signaling maintains hematopoietic stem cells in the niche. Cell. 2012;150(2):351–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Kohara H, et al. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006;25(6):977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki N, Ohneda O, et al. Combinatorial Gata2 and Sca1 expression defines hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow niche. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(7):2202–2207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508928103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taichman RS, Emerson SG. Human osteoblasts support hematopoiesis through the production of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1994;179(5):1677–1682. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.5.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]