Abstract

Background

Transaxillary thyroidectomy (TAT) has gained popularity in East Asian countries; however, to date there have been no attempts to evaluate the preferences regarding TAT in the United States population. The aim of this study is to assess the preferences and considerations associated with TAT in an American cohort.

Methods

Self-administered surveys were distributed to 966 adults at various locations in a single state. Questions assessed preferences for the surgical approach, acceptable risks and extra costs, and willingness to pursue TAT despite reduced cancer treatment efficacy.

Results

The response rate was 84% with a mean age of 40±17 years. The majority of respondents were female. Eighty-two percent of the respondents preferred TAT to a cervical thyroidectomy (CerT), all risks being equal. Fifty-one percent of the respondents were willing to accept a 4% complication rate with TAT. Sixteen percent of the respondents stated they would agree to pay up to an additional $5,000 for the TAT approach. When presented with thyroid cancer, 20% of all respondents still preferred TAT even if it would not cure their disease. Patients preferring TAT over CerT were younger, female, more willing to accept complications and spend additional money, and most significantly, preferred the TAT approach even if it was less likely to cure their cancer.

Conclusions

Although this survey presents a hypothetical question for people who do not have thyroid disease, the majority of respondents preferred TAT over CerT. Furthermore, a substantial number were willing to accept higher complication rates and increased costs for TAT.

Keywords: thyroidectomy, surgical approach, survey, transaxillary, cervical

Introduction

First described by Kocher in 1912, the transverse cervical approach for thyroidectomy has become the standard approach by surgeons in North America and typically requires a 3–6cm incision.1–4 Over the last century, new tools such as endoscopic thyroidectomy have progressed towards decreasing the length of the incision and minimizing the cervical scar. In 2006, Yoon et al introduced the gasless transaxillary endoscopic thyroidectomy, and more recently Kang et al published their work on incorporation of the surgical robot to transaxillary thyroidectomy (TAT).5, 6 It has been suggested that TAT spares patients the risk of postoperative hypoesthesia and fibrotic contracture within the anterior neck that can be a complication of the cervical approach.3, 7, 8 TAT has been met with much favor in East Asian countries where neck cosmesis is highly valued.9, 10 In contrast, TAT has not gained the same popularity in the United States. There are multiple reasons for this, the most common being that the procedure is more expensive, more time consuming, and that it would be significantly more dangerous when applied to the larger body habitus of the North American patient.11–13 Additionally, greater postoperative pain and the increased amount of dissection required to reach the thyroid gland are more reasons why North American’s have not opted for this approach.3, 10

With an increasing emphasis on patient-centered care and individualizing treatment, it is important to consider this new technique when offering surgical treatment of thyroid disease.14 That being said, Perrier et al remind us that “ultimately, it is the surgeon’s responsibility to the patient that must override all other concerns and requires a thoughtful, measured, and cautious approach during initial implementation of developing technologies.”12 This is especially true when planning surgical intervention for the patient with a thyroid malignancy.

Several studies in the United States have shown that with surgeon experience, operative times can decrease significantly which correlates to decreased operative costs.13, 15 American studies have shown that while the lateral approach poses a new challenge to surgeons with regards to visualization of important structures, the complication rates of TAT and cervical thyroidectomy (CerT) are fairly similar in the hands of an experienced endoscopic thyroid surgeon.12 This echo’s the findings seen in larger Korean studies, and a 2012 meta-analysis by Jackson et al which concluded that “robotic thyroidectomy is safe, feasible and efficacious as conventional cervical and endoscopic thyroidectomy,” with superior cosmetic satisfaction.8, 16–19

Even though several surgical departments in North America are now offering TAT and publishing their outcomes, there has been no attempt to evaluate the preference of the general population toward CerT versus TAT in the United States.13, 15, 20, 21 As thyroid cancer accounts for approximately 2% of all newly diagnosed malignances with over 100,000 thyroid operations performed annually, it is important to understand the preference of the general population with regards to risk, cost, and cosmesis of surgery.3, 22 The aim of this study is to evaluate, for the first time, patient sentiment regarding thyroidectomy approach through a large survey designed and distributed to adult members of the general population.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin.

Survey Design

Survey questions were designed to assess preferences for surgical approach, level of acceptable risk, willingness to absorb extra costs, and willingness to pursue TAT despite possibly reduced efficacy for the treatment of carcinoma. We began by asking respondents if they had ever had surgery, and how important the surgical scar was to them. To assess a preferred approach, we provided the subjects with a hypothetical scenario in which they were to undergo thyroidectomy for a benign thyroid lesion. The incision site and length were described for the two approaches, using text and sketch illustrations (Appendix). The risk of complications for each was assumed to be identical, and subjects were asked to choose the approach they would favor under these circumstances.

Acceptable level of risk was assessed by presenting a risk of complications for the cervical approach as 1 out of 100, and then asking the subject to qualify their willingness to accept TAT as the risk of complications increased incrementally from 1 out of 100 to 2, 4, 10 & 50 out of 100. The amount of out of pocket cost that the subjects would find acceptable was assessed by asking them to qualify their willingness to spend up to an additional $0, 500, $1,000, $5,000, $10,000 or $20,000 out of pocket. Finally, subjects were presented with a hypothetical vignette in which they had been diagnosed with cancer and told that TAT may not cure the cancer as well as the cervical approach. With this information, they were then asked to once again qualify their preference for TAT. We also collected basic demographic data including age, gender, level of education, race/ethnicity, and overall perceived health status.

Prior to administering the surveys, we validated survey questions with cognitive iteratively interviewing of ten individuals. These respondents were asked to describe what they thought each question meant, and as a result, two questions had to be rephrased for the final survey.

Data Collection

Between August 21st 2012 and November 5th 2012, self-administered surveys were distributed in person to 966 consecutive adults over the age of 18, members of the general public. The surveys were handed out at various public locations within 350 miles of the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics. Locations surveyed included the state capital building, shopping malls, public libraries, dining establishments, outpatient physician offices, bus stops, independent living facilities, movie theaters, grocery stores, coffee houses, and general downtown areas. Surveys were handed directly to participants, and no incentives were provided for completion. Response rate was calculated as the ratio of respondents out of the number of people approached.

Analysis

All returned surveys were included in our study. Survey data was entered into an Excel spreadsheet for further analysis of basic demographic data. We used SPSS Inc. statistical software to perform bivariate analysis in order to compare respondents who preferred the TAT approach to those who preferred traditional thyroidectomy. Comparisons were made with the student’s t-test, Chi-squared test, or the Fisher’s exact test. Finally, answers were dichotomized to use multivariate regression. We used STATA statistical software to conduct multivariate logistic regression to identify factors independently associated with respondents’ surgical approach preference. Our final models included gender, age, educational level, ethnicity, health status, scar importance, and previous surgery. Only factors at p=0.1 on bivariate analysis were included in the model.

Results

All respondents

The response rate for the survey was 84% (812 completed of 966 individuals approached). The mean age of all respondents was 40 ± 17 years with a slight female predominance (57%). Respondent characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Respondents’ characteristics (n=812)

| Characteristic | n(%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 460 (57%) | |

| Previous surgery | 495 (61%) | |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 622 (77%) |

| Asian | 63 (8%) | |

| African American | 41 (5%) | |

| Hispanic | 71 (8%) | |

| Other | 15 (2%) | |

| Highest education level | Elementary | 7 (1%) |

| High-school | 165 (20%) | |

| College | 424 (52%) | |

| Grad school | 214 (26%) | |

| Health status | Excellent | 223 (27%) |

| Very good | 348 (43%) | |

| Good | 202 (25%) | |

| Fair | 37 (5%) | |

| Poor | 4 (1%) | |

With regards to the preferences of our population, 24% of the respondents stated that the scar from surgery was “very important” to them, 41% found it to be “somewhat important”, 24% “a little important”, and only 11% said that the scar was “not at all important”. When presented with a hypothetical scenario of having a “thyroid lump that is not cancer” removed by either TAT (3 inch incision under the armpit) or traditional CerT (1.5 inch neck incision) if the “chance of a bad outcome was the same”, 82% stated that they would prefer TAT.

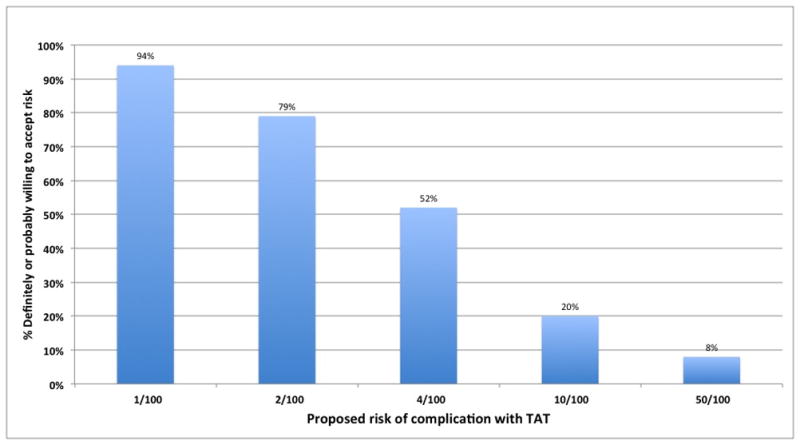

When told “the risk for a problem with surgery through the neck is 1 out of 100” and asked “What risk would you be willing to accept for surgery through the arm pit?” 415 (52%) and 160 (20%) of all respondents were willing to at least probably accept a 4% and 10% complication rate with TAT, respectively. As seen in Figure 1, there was a clear decrease in the percentage of respondents who were willing to accept an increased complication rate.

Figure 1.

Acceptable risk of TAT for the entire population surveyed

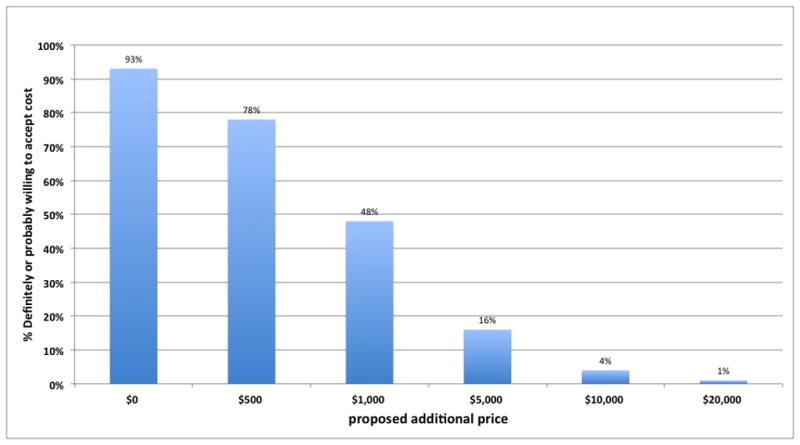

When asked “if you had to pay extra money for the arm pit surgery, how much more would you be willing to spend?” the overwhelming majority of respondents, 625 (78%), said that they would be “probably willing” to spend up to an additional $500. Nearly half, 383 (48%), would pay up to $1,000 and 132 (16%) of respondents said they would pay up to an additional $5,000. As seen in Figure 2, as the price increased there was a clear decline in the percentage of respondents who were willing to accept an increased personal cost for TAT.

Figure 2.

Price all respondents were willing to pay for TAT

Finally, when presented with the hypothetical diagnosis of thyroid cancer, and told that “the arm pit surgery might not cure your cancer as well,” 4% and 16% of respondents said that they would definitely or probably still proceed with TAT, respectively. In contrast, 29% and 51% stated they would probably not or definitely not proceed with TAT, respectively.

TAT vs. CerT

As shown in Table 2, those preferring TAT were significantly younger (39±17 vs. 46±19 years, p<0.0001) and predominantly female (59% vs. 47%, p=0.01). They were more concerned with their surgical scar and more commonly had undergone prior surgeries. Female gender and age younger than 40 years were independent predictive factors of TAT preference on multivariate analysis (OR=1.60, p<0.01 and OR=0.99, p<0.01, respectively). Patients who considered the scar important and patients who had previous surgery were also significant factors on multivariate analysis (OR=2.15, p<0.01 and OR=2.15, p<0.01, respectively).

Table 2.

TAT vs. CerT (Bivariate analysis as well as multivariate analysis with CerT as the referent).

| Characteristic | CerT (n=155) | TAT (n=657) | Bivariate p | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 46±19 | 39±17 | <0.01* | 0.98 (0.97 – 0.99) | |

| Female gender | 47% | 59% | <0.01 | 1.30 (1.12 – 1.94) | |

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 77% | 77% | 0.91 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| Asian | 9% | 8% | |||

| African American | 4% | 5% | |||

| Hispanic | 9% | 9% | |||

| Other | 1% | 1% | |||

| Education | Elementary - High-school | 16% | 22% | 0.12 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| College | 52% | 52% | |||

| Grad school | 32% | 25% | |||

| Health status | Excellent | 25% | 28% | 0.18 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| Very good | 42% | 43% | |||

| Good | 27% | 24% | |||

| Fair-Poor | 7% | 5% | |||

| Feel that scar is important (somewhat, very) | 50% | 69% | <0.01 | 2.15 (1.47 – 3.16) | |

| Previous surgery | 27% | 42% | <0.01 | 2.15 (1.41 – 3.28) | |

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test (data are not normally distributed)

TAT and complication risk

The responses of the survey’s respondents regarding the different complication risks are presented in Figure 1. Responses regarding 4/100 complication risks were further analyzed (Table 3). On bivariate analysis, respondents who would accept TAT with a 4/100 risk were more likely to be younger than 40 and have concerns about scar. On multivariate analysis, respondents older than 40 were 40% less likely to choose TAT if the risk was 4/100. Respondents who were concerned about their scar were 60% more likely to choose TAT at similar risk level.

Table 3.

TAT and complication risk (Bivariate analysis as well as multivariate analysis with referents within the variables).

| Characteristic | Would accept 4% risk for TAT | Bivariate p | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <40 | 59% | <0.01 | Ref 0.61 (0.46 – 0.81) |

| >40 | 45% | |||

| Gender | Female | 56% | 0.82 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| Male | 46% | |||

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 48% | 0.75 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| Asian | 55% | |||

| African American | 61% | |||

| Hispanic | 65% | |||

| Other | 57% | |||

| Education | Elementary - High- | 52% | 0.58 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| school | ||||

| College | 57% | |||

| Grad school | 40% | |||

| Health Status | Excellent | 57% | 0.50 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| Very good | 56% | |||

| Good | 42% | |||

| Fair-poor | 24% | |||

| Feel that | (Somewhat, very) | 66% | <0.01 | 1.62 (1.27 – 2.12) Ref |

| scar is Important | (Not at all, a little) | 42% | ||

| Previous Surgery | Yes | 53% | 0.86 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| No | 48% | |||

TAT and cost

The responses of the survey’s respondents regarding the associated extra costs are presented in Figure 2. Responses regarding $1,000 extra cost for TAT were further analyzed (Table 4). On bivariate analysis, respondents who would accept TAT with $1,000 extra cost were more likely to be younger than 40 and have concerns about scar. On multivariate analysis, respondents older than 40 were 40% less likely to choose TAT if the extra cost was $1,000. Respondents who were concerned about their scar were 54% more likely to choose TAT with similar costs.

Table 4.

TAT and cost (Bivariate analysis as well as multivariate analysis with referents within the variables).

| Characteristic | Would be willing to pay extra $1,000 for TAT | Bivariate p | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <40 | 56% | <0.01 | Ref 0.58 (0.44 – 0.77) |

| >40 | 39% | |||

| Gender | Female | 49% | 0.18 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| Male | 47% | |||

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 47% | 0.20 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| Asian | 44% | |||

| African American | 50% | |||

| Hispanic | 54% | |||

| Other | 52% | |||

| Education | Elementary - High- school | 48% | 0.14 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| College | 50% | |||

| Grad school | 44% | |||

| Health Status | Excellent | 53% | 0.11 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| Very good | 47% | |||

| Good | 46% | |||

| Fair-poor | 40% | |||

| Feel that scar is Important | (Somewhat, very) | 53% | <0.01 | 1.54 (1.14 – 2.08) Ref |

| (Not at all, a little) | 45% | |||

| Previous Surgery | Yes | 47% | 0.36 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| No | 49% | |||

TAT and cancer

When presented with the scenario of thyroid cancer and a hypothetical statement that the “the arm pit surgery might not cure your cancer well”, as many as 20% of the respondents said that they would definitely or probably proceed with TAT. This response was more common in respondents under the age of 40 but reach only marginal statistical significance (p=0.04). None of the variables analyzed reached statistical significance on multivariate analysis (Table 5).

Table 5.

TAT and cancer (Bivariate analysis as well as multivariate analysis with referents within the variables).

| Characteristic | Would prefer TAT even if might not cure cancer | Bivariate p | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <40 | 23% | 0.04 | Ref 0.99 (0.98 – 1.00) |

| >40 | 17% | |||

| Gender | Female | 17% | 0.24 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| Male | 23% | |||

| Ethnicity | Caucasian | 20% | 0.57 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| Asian | 18% | |||

| African American | 20% | |||

| Hispanic | 23% | |||

| Other | 8% | |||

| Education | Elementary – High-school | 23% | 0.62 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| College | 19% | |||

| Grad school | 22% | |||

| Health status | Excellent | 18% | 0.24 | Not in model p>0.1) |

| Very good | 20% | |||

| Good | 21% | |||

| Fair-poor | 27% | |||

| Feel that scar is Important | (Somewhat, very) | 20% | 0.12 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| (Not at all, a little) | 14% | |||

| Previous surgery | Yes | 19% | 0.60 | Not in model p>0.1 |

| No | 22% | |||

Discussion

The survey administered to our participants offered a hypothetical situation in which they had a thyroid nodule that required surgical removal. To our surprise there was an overwhelming interest in TAT and respondents were significantly willing to accept additional cost and associated risk in order to have the TAT procedure. Nearly a quarter of the entire population surveyed said that the surgical scar was “very” important to them, and another 41% said it was “somewhat” important. Younger patients were more prone to prefer the TAT approach and age was consistently a significant predictor of risk and cost acceptance as well as TAT preference, even when TAT was less likely to cure cancer. Concern over the surgical scar was most likely the driving force behind 82% of our respondents preferring the TAT approach in the setting of benign disease and scar importance was another predictor of cost acceptance. The significance of these findings is that while the surgeon may dismiss cosmesis as a factor that should not trump safety, this may be a risk that the patient is willing to accept. This must be factored into the thyroidectomy planning process, and future studies should further explore this phenomenon.

Several previous studies have evaluated patient satisfaction with cosmetic results and have come to different conclusions. Bellantone et al demonstrated that patients who underwent video-assisted thyroid lobectomy were significantly more likely to be “very satisfied” with the cosmesis of their scar.23 In contrast, Linos et al found no statistical difference in patient satisfaction with cosmesis between minimally invasive and conventional cervical incision. Of note, the researchers specifically asked the subjects, retrospectively, if they would rather have had a transaxillary procedure, to which 81% responded that they would not. Lang and Wong (2010) also performed a retrospective analysis of cosmetic satisfaction.24 Subjects in this study underwent either MIS video-assisted thyroidectomy or gasless transaxillary endoscopic thyroidectomy. Interestingly, they also found no difference in cosmetic satisfaction at 6-month follow up. A significant limitation to this study was that patients were randomized to each procedure by individual preference, creating a potential bias from the start. In a more recent study, Linos et al retrospectively evaluated patient attitudes toward transaxillary robotic-assisted thyroidectomy and demonstrated that only 11.6% of the patients preferred TAT.25 All these studies are limited to retrospective evaluation of patients who already had surgery, and in contrast, our study offers the perspective of evaluating hypothetical options in non-surgical candidates.

Since its introduction, endoscopic surgery for the thyroid has been controversial. Inabnet asked the question “should we embrace a technique when safer, less complicated, and cheaper alternatives exist?” to which his response was “no.”22 In this aspect the respondents to this survey raise a serious concern. A significant proportion of the respondents were willing to accept an increased complication rate. This significant difference was consistent for a complication rate that is up to four times the complication rate associated with CerT. In conjunction with the willingness to pay more money for the TAT approach, ethical dilemmas may need to be addressed. Is it the surgeon’s decision to decide between procedures when increased risks are involved and the patient is willing to accept those risks? Another concern is whether doubling the complication risk in surgeries that carry a 1–2% complication risk can be considered “safe enough” in order to be presented as a valid and equal option for patients. As presented by Gutknecht et al, patients do not fully comprehend the concept of a complication rate before surgery.26 This could be an explanation for why patients may be easily persuaded to agree to a procedure that offers improved cosmesis while harboring increased complication rate.

Furthermore and perhaps more importantly, our study demonstrates that 20% of respondents still prefer the TAT approach even if it is associated with a decreased chance for curing cancer. We are confident that the majority of surgeons would agree that in such a case, the cosmetic consideration should not take priority; however, one cannot ignore the patient’s preference, even in the setting of malignancy. There is a need for an honest and transparent debate as to whether this decision can be left to the individual surgeon who performs both approaches, or if every country’s national surgical society should interfere and propose guidelines for such cases. As a part of A New Technology Task Force, Perrier et al published guiding principles that serve as a framework for the safe implementation of emerging technologies in thyroid surgery, including TAT.12 Nevertheless, the final decision is up to the surgeon and the patient, and in that sense, our study provides important data on the patients’ preferences and willingness to accept associated risks and costs even in face of malignancy.

We believe that this study is a strong first step in evaluating the true perceptions of the general population; however, there are a few shortcomings. Perhaps the greatest disadvantage in our study is that it was designed to present a hypothetical scenario to respondents who do not have thyroid disease. Further evaluations of patient perception should take place in a more formal setting and involve a sampling of patients with diagnosed thyroid nodules. Another shortcoming is that the survey presented limited details on the entire surgical process and the specific complications of each approach, and showed drawings of scars as opposed to actual pictures or multimedia models. As a study by Bollschweiler et al (2008) demonstrated, adding a multimedia-based information system prior to cholecystectomy significantly increased patient perceived understanding of pathophysiology and the planned procedure.27 In this aspect it is clear that in the survey setting, the respondents’ perception of the different considerations was limited at best. In addition, our respondents were primarily college educated Caucasians, and we would recommend that future studies include a more heterogeneous population.

In conclusion, this is the first study that evaluates patient preferences regarding preferred thyroidectomy approach in a United States population. Although this survey presents a hypothetical decision for people who do not have thyroid disease, the majority of this random sample of US residents preferred TAT over traditional CerT when outcomes were equal. A substantial number were even willing to accept higher complication rates, increased costs, and decreased efficacy in the setting of cancer.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant 9U54TR000021 (Dr. Schwarze).

We would like to thank Mohammed Chohan, Megan Hannigan, Zach Nigogosyan, Devin Snyder, Amanda Timek, Perla Lozoya, Mariah Clark, Miles Russell, Emily Biersdorf, Adrian Ng, Demitri Price, Lisa Wendt, Matthew Holtz, Mayra Miranda, Leema John, Johnathon McCormick, and Delaney Wagener for their assistance with the survey distribution.

References

- 1.Kocher A. Discussion on Partial Thyroidectomy under Local Anaesthesia, with Special Reference to Exophthalmic Goitre. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1912;5:89–96. doi: 10.1177/003591571200501624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris R, Ryu H, Vu T, et al. Modern approach to surgical intervention of the thyroid and parathyroid glands. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2012;33:115–122. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazeh H, Chen H. Advances in surgical therapy for thyroid cancer. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:581–588. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhiman SV, Inabnet WB. Minimally invasive surgery for thyroid diseases and thyroid cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:665–668. doi: 10.1002/jso.21019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon JH, Park CH, Chung WY. Gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy via an axillary approach: experience of 30 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2006;16:226–231. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200608000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang SW, Lee SC, Lee SH, et al. Robotic thyroid surgery using a gasless, transaxillary approach and the da Vinci S system: the operative outcomes of 338 consecutive patients. Surgery. 2009;146:1048–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel D, Kebebew E. Pros and cons of robotic transaxillary thyroidectomy. Thyroid. 2012;22:984–985. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.2210.ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang SW, Jeong JJ, Yun JS, et al. Robot-assisted endoscopic surgery for thyroid cancer: experience with the first 100 patients. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2399–2406. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang BH. Minimally invasive thyroid and parathyroid operations: surgical techniques and pearls. Adv Surg. 2010;44:185–198. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang BH, Lo CY. Technological innovations in surgical approach for thyroid cancer. J Oncol. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/490719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cabot JC, Lee CR, Brunaud L, et al. Robotic and endoscopic transaxillary thyroidectomies may be cost prohibitive when compared to standard cervical thyroidectomy: a cost analysis. Surgery. 2012;152:1016–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perrier ND, Randolph GW, Inabnet WB, et al. Robotic thyroidectomy: a framework for new technology assessment and safe implementation. Thyroid. 2010;20:1327–1332. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuppersmith RB, Holsinger FC. Robotic thyroid surgery: An initial experience with North American patients. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:521–526. doi: 10.1002/lary.21347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tufano RP, Kandil E. Considerations for personalized surgery in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2010;20:771–776. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandil EH, Noureldine SI, Yao L, et al. Robotic transaxillary thyroidectomy: an examination of the first one hundred cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.01.002. discussion 564–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KE, Koo do H, Kim SJ, et al. Outcomes of 109 patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma who underwent robotic total thyroidectomy with central node dissection via the bilateral axillo-breast approach. Surgery. 2010;148:1207–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang SW, Jeong JJ, Nam KH, et al. Robot-assisted endoscopic thyroidectomy for thyroid malignancies using a gasless transaxillary approach. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J, Nah KY, Kim RM, et al. Differences in postoperative outcomes, function, and cosmesis: open versus robotic thyroidectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:3186–3194. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1113-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang SW, Jeong JJ, Yun JS, et al. Gasless endoscopic thyroidectomy using trans-axillary approach; surgical outcome of 581 patients. Endocr J. 2009;56:361–369. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k08e-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landry CS, Grubbs EG, Warneke CL, et al. Robot-assisted transaxillary thyroid surgery in the United States: is it comparable to open thyroid lobectomy? Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1269–1274. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landry CS, Grubbs EG, Morris GS, et al. Robot assisted transaxillary surgery (RATS) for the removal of thyroid and parathyroid glands. Surgery. 2011;149:549–555. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inabnet WB. 3rd Robotic thyroidectomy: must we drive a luxury sedan to arrive at our destination safely? Thyroid. 2012;22:988–990. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.2210.com2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellantone R, Lombardi CP, Bossola M, et al. Video-assisted vs conventional thyroid lobectomy: a randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2002;137:301–304. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.3.301. discussion 305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lang BH, Wong KP. A comparison of surgical morbidity and scar appearance between gasless, transaxillary endoscopic thyroidectomy (GTET) and minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy (VAT) Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:646–652. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2613-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linos D, Kiriakopoulos A, Petralias A. Patient Attitudes toward Transaxillary Robot-assisted Thyroidectomy World. J Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutknecht S, Kaderli R, Businger A. Perception of semiquantitative terms in surgery. Ann Surg. 2012;255:589–594. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824531ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bollschweiler E, Apitzsch J, Obliers R, et al. Improving informed consent of surgical patients using a multimedia-based program? Results of a prospective randomized multicenter study of patients before cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2008;248:205–211. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318180a3a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]