Abstract

Objective

Although stigma may have negative psychosocial and behavioral outcomes for patients with lung cancer, its measurement has been limited. A conceptual model of lung cancer stigma and a patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure is needed to mitigate these sequelae. This study identified key stigma-related themes to provide a blueprint for item development through thematic analysis of semi-structured interviews and focus groups with lung cancer patients.

Methods

Participants were recruited from two outpatient oncology clinics and included: a) 42 lung cancer patients who participated in individual interviews and, b) 5 focus groups (inclusive of 23 new lung cancer patients). Never smokers, long-term quitters, recent quitters, and current smokers participated. Individual interviews facilitated theme development and a conceptual model of lung cancer stigma, whereas subsequent focus groups provided feedback on the conceptual model. Qualitative data analyses included iterative coding and validation with existing theory.

Results

Two main thematic elements emerged from interviews with lung cancer patients: perceived (felt) stigma and internalized (self) stigma. Discussions of perceived stigma were pervasive, while internalized stigma was more commonly endorsed among current and recently quit smokers. Participants also discussed maladaptive (e.g., decreased disclosure) and adaptive (e.g., increased advocacy) stigma-related consequences.

Conclusions

Results indicate widespread acknowledgment of perceived stigma among lung cancer patients, but varying degrees of internalized stigma and associated consequences. Next steps for PRO measure development are item consolidation, item development, expert input, and cognitive interviews before field testing and psychometric analysis. Future work should address stigma-related consequences and interventions for reducing lung cancer stigma.

Keywords: lung cancer, cancer, oncology, stigma, patient-reported outcomes

Background

Lung cancer is the deadliest cancer, killing more people in the United States than breast, prostate, and colon cancer combined [1]. Despite recent advances in screening [2] and treatments [3], most lung cancers are still diagnosed at late stages and have poor treatment outcomes. Cigarette smoking represents a primary risk factor for lung cancer; over 80% of diagnoses occur in current or former smokers [4]. The well-established connection between smoking and lung cancer underscores the importance of smoking prevention and cessation interventions. However, this connection and public perceptions of smoking as a behavioral “choice” may also foster an unintended consequence, namely stigma against lung cancer patients [5-7]. Lung cancer patients with a smoking history (or who are assumed to have a smoking history) may be seen as responsible for and even deserving of this devastating illness [8-11].

Stigma may be associated with negative psychosocial outcomes among lung cancer patients [12-20]. Although empirical research is limited [20], some hypothesize that lung cancer stigma is related to diagnostic delays, limited use of adjunctive treatment and psychosocial support services, and low enrollment in clinical trials [21-26]. Investigators have also discussed the role that lung cancer stigma could play in discrimination, advocacy barriers, and under-prioritization of treatment and research funding [7, 16]. Mitigating lung cancer stigma could have widespread benefit for psychosocial adjustment, quality of medical care, and advocacy efforts.

The study of stigma has been heavily influenced by the work of Goffman (1963), who related stigma to an “attribute that is deeply discrediting” (p. 3)[27]. Other scholars [28, 29] have extended Goffman’s discussion and focused on stigma as a “mark (attribute) that links a person to undesirable characteristics (stereotypes)” (p.365) [30]. Stigma measurement has focused on public attitudes and discriminatory actions, along with the impact of this devaluation on affected individuals [31-33].

Studies of health-related stigma have been prominent in recent years, focusing on the social processes of stigma and its consequences within HIV/AIDS, mental illness, and epilepsy [33]. Despite preliminary data and commentaries about its prevalence and negative impact, the measurement of lung cancer stigma has been limited. Existing measures have been adapted from other disease contexts with little consideration of stigma-related concerns specific to lung cancer patients [19, 34]. Those few explicitly developed for lung cancer populations draw on observation from health professionals but have not incorporated significant patient perspective to inform item development [12, 14]. As the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and others have recently asserted, incorporating patient perspective is essential for both identifying relevant, population-appropriate constructs and developing validated patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments [35, 36]. Systematic analysis of patient-reported data is crucial to advancing a conceptual model of lung cancer stigma that leads to robust, empirically derived measurement tools. Without such data, inadequate measurement represents a significant barrier to identifying and addressing perceived stigma among lung cancer patients.

To address the need for systematic patient input into PRO measurement tools, this study focused on identifying key stigma-related themes through in-depth, semi-structured interviews with individuals diagnosed with lung cancer. Through careful, iterative coding of interview data, we developed a conceptual framework focused on lung cancer stigma and conducted patient focus groups to confirm the model’s relevance. Overall, these qualitative data improve our conceptual understanding of stigma and its consequences for lung cancer patients, along with providing a blueprint for subsequent PRO measurement of stigma.

Methods

Participants

Our sample was recruited through facilities at the UT Southwestern Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center, including Parkland Health & Hospital System and University Hospital. Individuals with a confirmed lung cancer diagnosis (both NSCLC and SCLC, any stage) were identified through treating medical oncologists at outpatient clinics and recruited by trained research staff. We excluded patients who did not speak English, or had a speech or cognitive impairment that rendered them incapable of informed consent and/or participation. To capture data from patients with varied smoking histories, recruitment was stratified based on smoking status at time of interview (never smokers, long term [>5 year] quitters, recent quitters [patients who quit smoking after their lung cancer diagnosis], and current smokers). Participants gave written consent for study participation and were compensated with a gift card ($15). The study was approved by the UT Southwestern Institutional Review Board (STU 072010-137).

Individual Interviews

Semi-structured interview goals included: 1) allowing patients to describe in their own words the degree to which they may or may not have experienced stigma; 2) exploring the role that smoking history plays in stigma, and 3) investigating stigma’s impact on emotional adjustment, interpersonal communication, and treatment-related behavior. In preparation for the individual interviews, an interview framework was developed to guide discussions. Notably, so as to allow patients to discuss their concerns with minimal investigator intrusion, the word “stigma” was not introduced in the interviews unless the participant mentioned it first or during the interview debriefing (see Appendix for Interview Guide).

Of the 54 patients who were deemed eligible by the treating medical oncologist and approached by research staff, 42 (78%) participated in an individual interview (patient characteristics in Table 1, left column). The most commonly stated reason for refusal among the other 12 eligible patients was lack of time. Interviews were conducted in private rooms by the Principal Investigator (HAH), a health psychologist with training and experience in oncology settings. The interviewer did not have any pre-existing relationships with the participants. A professional service transcribed the audio-recorded interviews verbatim. Investigators ceased recruitment upon achieving thematic saturation in interview analysis [37, 38].

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristics | Interview (n=42) n (%) |

Focus Group (n=23) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Sex

| ||

| Male | 20 (48%) | 12 (52%) |

| Female | 22 (52%) | 11 (48%) |

|

| ||

|

Education

| ||

| 11th grade or less | 7 (17%) | 1 (4%) |

| High school graduate or GED | 9 (21%) | 5 (22%) |

| Some college | 10 (24%) | 7 (30%) |

| College graduate | 8 (19%) | 6 (26%) |

| Post graduate training | 8 (19%) | 4 (17%) |

|

| ||

|

Marital Status

| ||

| Married/Partnered | 29 (69%) | 18 (78%) |

| Divorced | 7 (17%) | 3 (13%) |

| Widowed | 2 (5%) | 1 (4%) |

| Single, never married | 4 (10%) | 1 (4%) |

|

| ||

|

Race

| ||

| White | 27 (64%) | 16 (70%) |

| Black/AA | 12 (29%) | 5 (22%) |

| AI or Alaska Native | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Asian or PI | 2 (5%) | 2 (9%) |

|

| ||

|

Ethnicity

| ||

| Hispanic | 6 (14%) | 1 (4%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 36 (86%) | 22 (96%) |

|

| ||

|

Cancer Stage

| ||

| Stage 1 | 5 (12%) | 3 (13%) |

| Stage 2 | 2 (5%) | 1 (4%) |

| Stage 3 | 11 (26%) | 4 (17%) |

| Stage 4 | 22 (52%) | 15 (65%) |

| Unstaged at time of interview | 2 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

|

| ||

|

Smoking Status

| ||

| Never smoker | 11 (26%) | 8 (35%) |

| Long term quitter (>5yrs) | 10 (24%) | 5 (22%) |

| Recent quitter (quit at diagnosis) | 11 (26%) | 6 (26%) |

| Current smoker | 10 (24%) | 4 (17%) |

|

| ||

|

Time since diagnosis

| ||

| < 6 months | 15 (36%) | 8 (35%) |

| 6 months to 2 years | 18 (43%) | 13 (56%) |

| >2 years | 9 (21%) | 2 (9%) |

Focus Groups

After completing and coding the interviews, we recruited 23 new patients to participate in 5 focus groups. The primary purpose of the focus groups was to validate and provide feedback on the conceptual model that emerged from patient interviews (focus group patient characteristics in Table 1, right column) [35, 36, 39]. Smoking status within groups was mixed to allow group dynamics that elicited a broader range of perspectives [40, 41]. All focus groups were led by the Principal Investigator (HAH) and Co-Investigator (SCL), a qualitative methods specialist with experience in focus group facilitation with lung cancer patients [42]. Using slides to guide participants through the conceptual model, we solicited reactions to each component, explaining how it had been derived from prior reports of patient experience and seeking opinions on relevance. In contrast to the more open-ended structure of the individual interviews, focus group members were asked to specifically consider the model’s relevance in light of their lung cancer experiences. Each 60-minute session was audio-recorded and professionally transcribed.

Data Analysis

A team of three research coders reviewed transcripts and evaluated patient responses using an inductive, text-driven approach to thematic content analysis [43, 44]. We identified emerging patterns and recurrent themes using line-by-line coding to compare and contrast (Nvivo 9, QSR International, AU). Initial open codes led to axial coding categories that were refined into more abstract, thematic codes and validated against other theoretical constructs related to stigma. To establish inter-rater reliability, team members systematically reviewed coding agreement and resolved discrepancies through consensus [45-50]. Investigators (HAH, SCL, JO) collectively identified preliminary themes, leading to theme consolidation and extraction, with subsequent iterative discussion and analysis by the whole team [46, 51].

As a strategy for member-checking, the conceptual model was presented in the focus groups for potential endorsement [43]. Following focus group sessions, investigators assessed participant responses and attitudes toward proposed conceptual domains [35, 36, 39]. Resulting transcripts were reviewed by research team members with special attention to model confirmation, negative cases, and other patient statements that deviated from the conceptual model.

Results

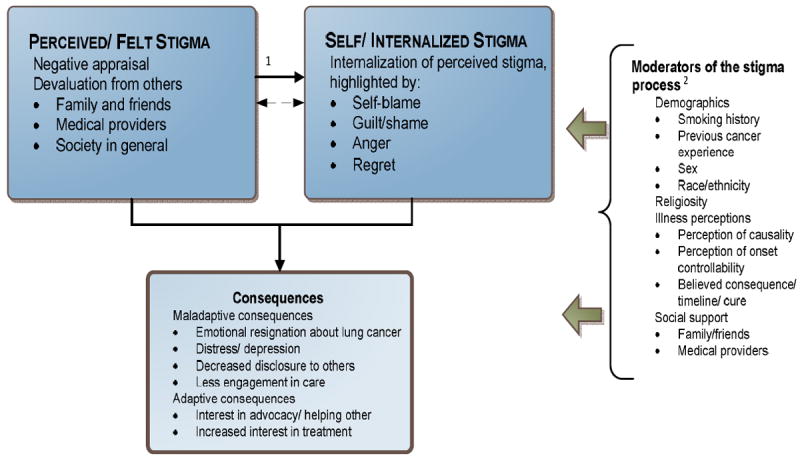

Qualitative analyses of individual interviews revealed two main themes. First, participants described their perceptions of others’ stigmatizing attitudes or behaviors, consistent with prior categorizations of “perceived” (or “felt”) stigma [33]. Second, they described “internalized” (or “self”) stigma responses characterized by self-blame, guilt, shame, anger and regret [31-33, 52]. As detailed in our conceptual model of the stigma process (Figure 1), perceptions of stigma from others are internalized by the individual, consistent with the process described by other stigma researchers [30, 31, 53, 54]. However, our model also suggests a negative feedback loop in which high levels of internalized stigma can also lead to increases in perceived stigma through expectations of negative experiences (i.e., “stigma consciousness”) [55-57].

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Lung Cancer Stigma

1Hypothesis–the primary direction goes from PF Stigma to SI Stigma. However, this could be a mutually reinforcing process between them once established

2Moderators can “buffer” or “exacerbate” experience and consequences of stigma

Perceived Stigma

As noted in Table 2, most (40 of 42; 95%) individual interviewees discussed at least one aspect of perceived stigma (100% never smokers, 90% long time quitters, 100% recent quitters, 90% current smokers). Many comments focused on how strangers or acquaintances immediately asked about smoking history when they learned of the participant’s lung cancer diagnosis (representative quotations in Table 3.1):

Table 2.

Summary of Individual Interview Themes

| Themes and Subthemes | Endorsement n (%) |

|---|---|

| Perceived/ Felt Stigma: Negative appraisal and devaluation from others | 40 (95%) |

| Family and friends | 26 (62%) |

| Medical providers | 20 (48%) |

| Society in general | 34 (81%) |

| Self/ Internalized Stigma: Internalization of perceived stigma | 25 (60%) |

| Self-blame/Guilt/Shame | 22 (52%) |

| Anger | 4 (10%) |

| Regret | 13 (31%) |

| Stigma-related Consequences | 41 (98%) |

| Maladaptive consequences | |

| Emotional resignation about lung cancer | 29 (69%) |

| Distress/ depression | 21 (50%) |

| Decreased disclosure to others | 20 (48%) |

| Less engagement in care | 20 (48%) |

| Adaptive consequences | |

| Interest in advocacy/helping others | 20 (48%) |

| Increased interest in treatment | 29 (69%) |

Table 3.

Representative participant quotations

| Perceived Stigma | |

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| 4 |

|

| Internalized Stigma | |

| 5 |

|

| 6 |

|

| 7 |

|

| Consequences | |

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| Moderators of the Stigma Process | |

| 14 | [Perception of Controllability]

|

| 15 | [Social Support]

|

| 16 | [Religiosity]

|

| 17 |

|

| 18 | [Believed Consequences]

|

But I think that’s how you associate it. Because the first thing they ask—even me, the first thing I would ever ask somebody was, “Did you smoke?” (Female, recent quitter)

Other patients discussed societal attitudes toward lung cancer and focused on discrepancies with other common cancers (Table 3.2):

Okay, how come I don’t have a ribbon for lung cancer? They’ve got these pretty little [pink] ribbons for breast cancer. How come I don’t have a pretty little ribbon? (Female, recent quitter)

Both smokers and nonsmokers reported negative appraisal and devaluation from family members, friends, and colleagues who learned about the patient’s lung cancer diagnosis (Table 3.3):

Some of my friends sort of moved away like I had the leprosy. You know, everybody got busy with their own life. (Female, recent quitter)

Almost half of participants reported negative responses from medical providers. Of note, were non-smokers who perceived judgmental smoking-related assumptions among members of their medical team (Table 3.4):

The first negative reaction I got was in the hospital, from the respiratory therapist. [Family member] heard her. She said this under her breath while I was having respiratory therapy post-op, “That’s what you get for smoking.” (Male, never smoker)

Focus group participants within all smoking categories strongly endorsed the relevance of perceived stigma and its subthemes. A few non-smoker participants denied personal experience with perceived stigma but described how they “preempt” stigmatizing reactions:

I will say that I’ve never felt any stigma, but I have this need to say immediately that I have never smoked. (Female, never smoker)

Internalized Stigma

Examples of internalized stigma were discussed in the majority of interviews, but were not as uniformly endorsed as perceived stigma (Table 2). More current smokers (90%) and those who quit at diagnosis (82%) discussed internalized stigma, compared to lower frequencies among long-term quitters (40%) and never smokers (27%). Guided by both social psychological frameworks [58, 59] and clinically focused models of self-blame, guilt, and shame [60, 61] we identified the following three subcategories of internalized stigma: 1) self-blame/guilt/shame, 2) anger, and 3) regret.

The decision to discuss self-blame, guilt, and shame within a single subtheme came after a detailed coding process. Based on distinctions of “guilt” as behavior-specific responses and “shame” as intractable, self-focused reactions [61], we attempted to code these emotions separately. We also attempted to distinguish behavioral self-blame (“I did something bad”) from characterological self-blame (“I am a bad person”) [62]. However, our data did not support such fine-grained distinctions, so self-blame, guilt, and shame were included in a single code.

Participants expressed internal self-blame and guilt that were often related to smoking and family impact (Table 3.5):

I feel guilty about it, in regards to the burden it’s put on [my husband] the stress it’s put on my children, my grandchildren. You know, I never gave it any thought. You know, and as a smoker, a risk taker, I failed to think of the risks, of what it will do to someone else. So I think I feel guilty about that. I really do. I just—you know, I don’t know how to make it right. (Female, recent quitter)

Despite fewer instances of internalized blame among never smokers, certain quotes illustrate self-blame and guilt (Table 3.6):

But I feel really guilty, and it’s as though—well, like I said, I’m not sure if I’m not blaming myself for having it. Although I don’t know what I did to do it, I feel guilty. I feel guilty. And it’s—it’s—it’s strange. I don’t think I would feel that guilty with anything else. (Male, never smoker)

Other patients reported more nuanced descriptions of self-blame or guilt. One participant expressed guilt conditional on the timing of his smoking cessation:

Oh, if I was still smoking, yes, I would feel guilty. Yeah, I sure- I surely would. Because, I mean, I think you’ve been warned, you’ve been warned, you’ve been warned. You know, I mean it’s just pounded into you for the longest time. (Male, long-term quitter)

Another interviewee denied the term “guilt” but described other negative emotions, such as regret:

Guilt isn’t the word I would use. It’s—there’s some sadness. It’s so unclear about what the actual cause was. You know, I wish I had handled stress better during that time, but to say I feel guilty about it is not true. (Female, long-term quitter)

This feeling of regret, especially as it related to smoking history, was echoed by other interview participants (Table 3.7):

You know…that feeling when you do something, you screw up, and you say, “Dumb! Why did I do this?” … I’ve been smoking for so long. I mean, I could just, “Dumb, dumb, dumb,” all day long, and it wouldn’t do any good because I have smoked for that many years. (Female, current smoker)

A few patients described anger toward government entities and/or tobacco companies:

Why in the world are they allowing the tobacco companies to continue without being fined? I’m very angry about our government letting this continue and not getting any help for smokers that want to quit. I get very angry about the—the way the tobacco companies have gotten away with it. (Female, current smoker)

Among focus group participants, we found generally strong support for the phenomenon of internalized stigma. Current and recently quit smokers particularly endorsed internalized stigma:

So I felt all those things, the guilt, shame, anger, regret, all those. (Male, current smoker)

Consequences

Our interview data suggest a diverse set of stigma-related consequences that we classified as either “maladaptive” or “adaptive” within the model (Figure 1; Table 2). The decision to divide consequences into these categories was based on both iterative analyses of the diverse data and theoretical guidance of stigma researchers who caution against exclusively negative interpretations of stigma-related consequences and encourage fuller understanding of advocacy and other adaptive actions [30, 63].

Some lung cancer patients reported emotional resignation related to their prognosis (Table 3.8):

It’s—it’s a little too late. God forbid if there’s a cure here, if I was, I went into remission. I would be totally, you know, shocked. But realistically I don’t think that’ll ever happen. I think I’m too far gone for that to happen. So I have to just look at it day by day, and [pause]—say to myself, you know, just make the most of it (Female, current smoker).

Others discussed psychosocial distress related to self-blame and their lung cancer diagnoses (Table 3.9):

I’ll be sitting there by myself at home and I’ll just bust out crying about it. [It’s] really when I’m by myself and…think about it but it all, it all falls back on myself …it all goes back to the smoking. (Female, current smoker)

For some patients, self-blame and concern about perceived stigma led to decreased disclosure about their lung cancer (Table 3.10):

I just keep it to myself. I don’t want people feeling sorry for me. You know, it’s my fault I guess that I’ve got it. It wasn’t theirs, so… (Male, recent quitter)

Patients discussed how stigma limited their involvement in treatment decisions and other medical care (Table 3.11):

The other side of it is—I kind of feel like I wasn’t smart enough to quit smoking, maybe I’m not smart enough to make the right decisions for my treatment for me. (Female, recent quitter)

For certain patients, stigma awareness fueled advocacy interest (Table 3.12):

The way I look at it is if I could get one or two people off of cigarettes or something, to learn from my experience, then it’s worth it. … I could use what I’m going through right now to maybe help others and stuff. (Male, recent quitter)

Other patients discussed being proactive and being more involved in treatment decision making (Table 3.13):

I’m good at writing questions down before I come in, becoming educated on the prescriptions and stuff, you know, what are the side effects. Because I look at it as being a team with the doctors. (Male, recent quitter)

Focus group participants within all smoking categories endorsed the existence of many maladaptive consequences related to stigma, even if they did not personally experience them. However, there was less agreement about reduced engagement in medical care, particularly among non-smokers in the groups:

I have a hard time with it [the idea of not pursuing all treatment options] …I don’t know too many people who wouldn’t want to continue with their treatments unless they were so far gone where nothing is working any more. (Female, never smoker)

Focus group participants affirmed the model’s focus on adaptive consequences of stigma, with a number of patients describing their own advocacy efforts.

I really try to be very open about it and to kind of be an advocate and talk to people about it. (Female, never smoker)

Discussion

By elucidating lung cancer patients’ perceptions of stigma, our qualitative work provides intensive patient perspective needed for PRO instrument development. Through careful development of our interview guide, recruitment of a diverse patient population, and an iterative process of data coding and member checking, we developed a patient-informed conceptual model of lung cancer stigma (Figure 1). Presenting the model and eliciting feedback from patient focus groups helped identify areas of significant consensus as well as variability within the model’s components.

Content and structure of conceptual model

Perceived Stigma

We found strong recognition of negative appraisal and devaluation by others (perceived stigma). Perceived stigma was not merely restricted to responses from specific others (e.g., blame from family members, acquaintances questioning a patient’s smoking history), but also reflected pervasive societal responses. A number of patients recognized noteworthy disparities in public awareness and resources devoted to lung cancer, especially in relation to breast cancer. Perceived stigma was so ingrained that some patients who were never smokers reported a need to preface their discussions of lung cancer with defensive disclosures denying smoking behavior.

One of the most important interpersonal relationships for lung cancer patients lies with their treatment providers. Patients’ mistrust of their treatment team can adversely affect clinical communication, treatment decision-making, and satisfaction with care [64, 65]. Although direct evidence is limited [20], preliminary work suggests that bias, blame, and nihilism (however unintentional) may play a role in clinicians’ interactions with their lung cancer patients and result in biased attitudes and actions [23, 66]. Our data offer further support in patient statements reflecting both negative interactions and perceived bias (often related to questions or assumptions of smoking history) with medical providers. More data are needed to understand the role of stigma and nihilism in clinician-patient interactions, along with its impact on interpersonal dynamics and treatment-related consequences. Promoting empathic and non-judgmental doctor-patient communication may be another target for stigma-reducing interventions [67].

Internalized Stigma

High levels of perceived stigma can be internalized by an individual and, in turn, manifest emotionally as guilt, shame, self-blame, regret, and anger [31, 32, 52]. However, our data suggest that this process is not as readily acknowledged by lung cancer patients. Whereas almost all participants reported some recognition of perceived stigma, internalized stigma was discussed disproportionately among individuals with a current or recent smoking history.

Our data suggest the importance of smoking history in understanding who is most affected by internalized stigma responses (Figure 1). Never smokers and those who quit long ago may perceive less “toxic” stigma from others (e.g., acquaintances who don’t know their smoking histories and more distant “society”). The stigma that smokers perceive from close family and friends appears more personalized and hurtful. Long-term quitters and never smokers may also be “buffered” against internalized stigma through beliefs about features, causes, and consequences of their lung cancer (i.e., illness perceptions [68]). A large body of psycho-oncology research shows the importance of illness perceptions (e.g., perceived causality, onset controllability, expected consequences) for psychosocial adjustment [69, 70]. For example, never smokers may rationalize that stigma is not self-relevant based on the “uncontrollable” cause of their lung cancer and deflect the impact through pre-emptive disclosures about non-smoking histories and other self-defensive assertions (Table 3.14).

Although internalized stigma was more frequently discussed among current smokers and recent quitters, it was not as prominent as might be expected. Certain moderating factors (e.g., high levels of social support from close others [Table 3.15] and religious coping [Table 3.16]) may attenuate the stigma processes in a subset of this group (Figure 1) [71]. Consistent with research showing that smokers attribute lung cancer to non-smoking causes, perceptions of lung cancer causality (Table 3.17) and consequences (Table 3.18) may also play a buffering role in that group [72]. These attributions may reconcile cognitive inconsistencies related to smoking and lung cancer risk (i.e., Festinger’s theory of dissonance [73]). Theorists have also discussed “disavowal” as a self-protective coping mechanism for lung cancer patients with recent smoking histories [74]. This defensive process may buffer the impact of stigma through denials (or questioning statements) about onset controllability and responsibility.

Among those participants who did endorse internalized stigma, some individuals made clear declarations of self-blame and guilt, whereas other statements were more nuanced. In addition, unlike perceived stigma, which was primarily driven by assumptions about smoking, internalized stigma was more varied in its attributions (e.g., smoking, second hand smoke exposure, stress). Although a few participants expressed anger at the tobacco industry, these statements were not pervasive and represent untapped targets for public health campaigns [7].

Stigma-related Consequences

Prior work has often framed stigma-related consequences as exclusively negative, with little consideration of more positive effects. Our data suggest that negative (or “maladaptive”) consequences of stigma do exist – we noted examples of emotional resignation, distress, and reduced illness-related disclosure tied to stigma. However, consistent with a few notable discussions of stigma [e.g., [30, 63]] our data also reveal strong endorsement of “adaptive” consequences of stigma, such as public health advocacy for increased lung cancer awareness and funding. Strong focus group endorsement of these adaptive consequences solidified the need for this separate category.

We found moderate support for negative treatment-related consequences of stigma. Some patients reported a “vulnerability” that limited involvement in treatment decisions and disclosure of illness-related concerns to medical personnel. However, it is not entirely clear that these issues are unique to lung cancer or stigma per se rather than features of life-threatening conditions. Further, these stigma-related treatment consequences were not uniformly endorsed within focus groups and other participants reported more active involvement in their medical care. We maintained these negative treatment-related consequences in the theoretical model, although the focus group feedback indicated that this construct clearly needs further clarification. The differential experience of stigma may help explain why some individuals report avoidance and isolation while others are mobilized by their diagnosis of lung cancer. Perhaps most significantly, these nuances point to the critical role of moderators such as illness perceptions and social support in the patient experience of lung cancer.

Study limitations

While our study recruited a diverse group of patients that reflected the area’s population, restricting the sample to English speakers was a potential limitation that may have reduced the number of Hispanic participants. However, our sample resembles national rates, as lung cancer incidence is lower among Hispanics [75]. Expressed personal responsibility for health and religiosity are common social values in Texas as in other southern states [76]; variation in the experience of stigma may be influenced by social geography [77-79].

Measure Development

These findings provide a foundation for continued focus on lung cancer stigma and its measurement. Consistent with steps outlined in development guidelines, our next steps for PRO measurement will focus on item consolidation, item development, expert input, and cognitive interviews with patients [36]. These processes will result in a robust measurement tool based on significant patient input and ready for field testing and psychometric analysis.

Intervention Development

Although our data do not directly address intervention needs, they do provide indications for future work in addressing stigma and its consequences. In other disease domains (e.g., HIV, serious mental illness), most intervention studies focus on stigma among community members and medical providers [80]. We know of no published intervention studies focused on reduction of lung cancer stigma among these groups, although advocacy organizations have recently integrated public awareness campaigns in attempts to lessen stigma within the community [81].

Across multiple disease domains, recent work has addressed the need for interventions for stigmatized individuals. For example, an investigation of acceptance-based psychotherapy (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; ACT) for stigma among substance abusers reported large effects for self-esteem and experiential avoidance (constructs similar to our conceptualization of stigma-related consequences) and medium effects for internalized stigma and shame [82]. Importantly, perceived stigma did not change, leading the authors to conclude that “perceived stigma is perhaps a less fruitful target for intervention”. Consistent with this assertion, we found that although perceived stigma is relatively ubiquitous among lung cancer patients, its diffuse nature may not be the best focus of intervention. Alternatively, future psychosocial interventions may focus on reducing the internalized impact and negative consequences of perceived stigma among patients with lung cancer. A better understanding of the differences among those who perceive stigma but report more adaptive consequences v. those who note high internalized stigma and maladaptive consequences will help guide the intervention development process. Existing therapeutic modalities that focus on cognitive-behavioral strategies and self-forgiveness (e.g., ACT, Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) may also be useful frameworks for interventions with lung cancer patients [83-85].

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (1R03CA154016) and the National Lung Cancer Partnership and its North Carolina Chapter (Young Investigator Award) to H.A.H. Partial support for J.S.O. provided by the Lung Cancer Research Foundation. The authors thank Silvia Pilarski at Parkland, and Laurin Loudat, Erin Fenske-Williams, and Rachael Skelton at UT Southwestern for their assistance coordinating patient logistics. Katharine McCallister, Maria Funes, Trisha Melhado, and Louizza Martinez provided valuable assistance in data analysis. We also thank Sharon Woodruff, Jeff Kendall, Dinah Foster, Cassidy Cisneros, Rachel Funk, and Nicole Else-Quest for their help in study conceptualization and conduct, as well as Elyse Shuk from MSKCC’s Behavioral Research Methods Core Facility for her comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Appendix

Interview Guide: Impact of Attitudes toward Lung Cancer

-

Opening Queries

-

Question: Tell me about your experience with lung cancer.

Probe: How were you first diagnosed with lung cancer?

Probe: How did you react when you first learned about your diagnosis?

Probe: How did your family, friends, and co-workers respond?

-

-

Allowing patients to describe in their own words what stigma means to them and the degree to which they may experience it.

-

Question: Some people with lung cancer report feeling badly about their diagnosis. Tell me a little bit about any bad feelings that you may have had about being diagnosed with lung cancer?

(Note: If Patient says, “What do you mean?”or is puzzled by the question: Can say “Some patients say that lung cancer in particular brings up feelings that patients with other cancers may not experience.”)

Probe: Are these feelings about cancer in general or are they specific to having lung cancer?

Probe: How are these feelings affected by your family and friends’ responses to you and your diagnosis?

Probe: How are these feelings affected by media or news stories about lung cancer?

Probe: Have these feelings made you think about other parts of your life differently?

-

-

Investigating the role that smoking plays in patients’ experiences with stigma.

-

Question: Some patients report that they spend a lot of time thinking about what caused their cancer. Can you describe any of these thoughts you have had?

Probe: How do these thoughts about what caused your cancer affect how you feel about yourself?

Probe: How much do other people’s questions about what caused your cancer affect you?

Probe: Do you react differently depending on whether the questions come from family and friends vs. people you don’t know very well?

-

-

Investigating the ways in which stigma may impact emotional adjustment, interpersonal communication, and behavior. (Use “think aloud” techniques for specific items to assist this goal; may pick and choose different items depending on what has and hasn’t been expressed so far.)

-

Question: Here are some thoughts that other people have had about their lung cancer diagnosis. Please talk about how, if at all, each statement is relevant to you and your experiences.

When people learn that I have cancer, they want to know what I did to cause it.

People are less sympathetic to me than they are to people with different types of cancer.

I feel guilty because I have lung cancer.**

Sometimes I feel that I have done something to deserve having lung cancer. *

There are times I don’t talk to friends and family about my cancer because I am concerned about being judged. *

Feeling bad about having lung cancer has negatively affected the way I advocate for myself in my medical appointments.

-

* Adapted from LoConte et al. (2008) Perceived Cancer Related Stigma measure.

** Adapted from Berger (2001) HIV Stigma measure.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. What are the key statistics about lung cancer? [1/18/ 2013]; Available from: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/lungcancer-non-smallcell/detailedguide/non-small-cell-lung-cancer-key-statistics.

- 2.Aberle DR, et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosell R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell K, et al. Smoking, stigma and tobacco ‘denormalization’: Further reflections on the use of stigma as a public health tool. A commentary on Social Science & Medicine’s Stigma, Prejudice, Discrimination and Health Special Issue (67: 3) Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(6):795–799. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayer R, Stuber J. Tobacco control, stigma, and public health: Rethinking the relations. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(1):47–50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gritz ER, et al. Building a united front: Aligning the agendas for tobacco control, lung cancer research, and policy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(5):859–863. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamann HA, Howell LA, McDonald JL. “You Did This to Yourself”: Causal Attributions and Attitudes Toward Lung Cancer Patients. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2013;43:E37–E45. doi: 10.1111/jasp12053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosher C, Danoff-Burg S. An Attributional Analysis of Gender and Cancer-Related Stigma. Sex Roles. 2008;59(11):827–838. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9487-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lobchuk MM, et al. Does blaming the patient with lung cancer affect the helping behavior of primary caregivers? Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(4):681–9. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.681-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lobchuk MM, et al. Impact of Patient Smoking Behavior on Empathic Helping by Family Caregivers in Lung Cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2012;39(2):112–121. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E112-E121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cataldo JK, et al. Measuring stigma in people with lung cancer: Psychometric testing of the Cataldo lung cancer stigma scale. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38(1):46–54. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.E46-E54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A. Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1470. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38111.639734.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LoConte NK, et al. Assessment of guilt and shame in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer compared with patients with breast and prostate cancer. Clinical Lung Cancer. 2008;9(3):171–178. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2008.n.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss T, et al. A 30-year perspective on psychosocial issues in lung cancer: how lung cancer “came out of the closet”. Thorac Surg Clin. 2012;22(4):449–56. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holland JC, Kelly BJ, Weinberger MI. Why psychosocial care is difficult to integrate into routine cancer care: stigma is the elephant in the room. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(4):362–6. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cataldo JK, Jahan TM, Pongquan VL. Lung cancer stigma, depression, and quality of life among ever and never smokers. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2012;16(3):264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Else-Quest NM, et al. Perceived stigma, self-blame, and adjustment among lung, breast and prostate cancer patients. Psychology & Health. 2009;24(8):949–964. doi: 10.1080/08870440802074664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez BD, Jacobsen PB. Depression in lung cancer patients: the role of perceived stigma. Psycho-Oncology. 2012;21(3):239–246. doi: 10.1002/pon.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chambers S, et al. A systematic review of the impact of stigma and nihilism on lung cancer outcomes. BMC Cancer. 2012;12(1):184. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Earle CC, et al. Impact of referral patterns on the use of chemotherapy for lung cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:1786–1792. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tod AM, Craven J, Allmark P. Diagnostic delay in lung cancer: a qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008;61(3):336–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wassenaar TR, et al. Differences in primary care clinicians’ approach to non-small cell lung cancer patients compared with breast cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(8):722–728. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3180cc2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corner J, Hopkinson J, Roffe L. Experience of health changes and reasons for delay in seeking care: a UK study of the months prior to the diagnosis of lung cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(6):1381–91. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jennens RR, et al. Differences of Opinion*A Survey of Knowledge and Bias Among Clinicians Regarding the Role of Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. CHEST Journal. 2004;126(6):1985–1993. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curran WJJ, et al. Addressing the Current Challenges of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Clinical Trial Accrual. Clinical Lung Cancer. 2008;9(4):222–226. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2008.n.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Penguin Books; London: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones EE, et al. Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. WH Freeman; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Link BG, C PJ. Labeling and stigma. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. The Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health. Plenum; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corrigan PW. The impact of stigma on severe mental illness. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1998;5(2):201–222. doi: 10.1016/s1077-7229(98)80006-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corrigan PW, Watson AC. The Paradox of Self-Stigma and Mental Illness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9(1):35–53. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.9.1.35. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Brakel WH. Measuring health-related stigma—A literature review. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2006;11(3):307–334. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lebel S, et al. The psychosocial impact of stigma in people with head and neck or lung cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pon.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothrock NE, Kaiser KA, Cella D. Developing a valid patient-reported outcome measure. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90(5):737–42. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.United States. Department of Health and Human Services. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. 235. Vol. 74. Food and Drug Administration; Rockville, MD: 2009. pp. 65132–65133. Federal Register http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822x05279903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health. 1995;18(2):179–183. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pusic AL, et al. Development of a New Patient-Reported Outcome Measure for Breast Surgery: The BREAST-Q. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;124(2):345–353. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bloor M, et al. Focus groups in social research. Sage; London: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuzel AJ. Sampling in qualitative inquiry. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1992. pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerber DE, et al. Patient comprehension and attitudes toward maintenance chemotherapy for lung cancer. Patient Education and Counseling. 2012;89(1):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. Sage; Newbury Park, California: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health services research. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen DJ, Crabtree BF. Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: controversies and recommendations. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):331–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Armstrong D, et al. The Place of Inter-Rater Reliability in Qualitative Research: An Empirical Study. Sociology. 1997;31(3):597–606. doi: 10.1177/0038038597031003015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hruschka DJ, et al. Reliability in Coding Open-Ended Data: Lessons Learned from HIV Behavioral Research. Field Methods. 2004;16(3):307–331. doi: 10.1177/1525822x04266540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lombard M, Snyder-Duch J, Bracken CC. Content Analysis in Mass Communication: Assessment and Reporting of Intercoder Reliability. Human Communication Research. 2002;28(4):587–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00826.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson C, et al. Increasing the visibility of coding decisions in team-based qualitative research in nursing. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2004;41(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mays N, Pope C. Rigour and qualitative research. Brit Med J. 1995;311(6997):109–12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6997.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The Self–Stigma of Mental Illness: Implications for Self–Esteem and Self–Efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25(8):875–884. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacoby A. Felt versus enacted stigma: a concept revisited: evidence from a study of people with epilepsy in remission. Social Science & Medicine. 1994;38(2):269–274. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scambler G, Hopkins A. Being epileptic: coming to terms with stigma. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1986;8(1):26–43. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11346455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pinel EC. Stigma Consciousness in Intergroup Contexts: The Power of Conviction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2002;38(2):178–185. doi: 10.1006/jesp.2001.1498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Santuzzi AM, Ruscher JB. Stigma salience and paranoid social cognition: Understanding variability in metaperceptions among individuals with recently-acquired stigma. Social Cognition. 2002;20(3):171–197. doi: 10.1521/soco.20.3.171.21105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pinel EC. Stigma consciousness: the psychological legacy of social stereotypes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(1):114–28. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.76.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Major B, O’Brien LT. The Social Psychology of Stigma. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56(1):393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weiner B. Judgments of responsibility: A foundation for a theory of social conduct. Guilford; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bulman RJ, Wortman CB. Attributions of blame and coping in the “real world”: Severe accident victims react to their lot. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1977;35(5):351–363. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.35.5.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tangney JP. Assessing individual differences in proneness to shame and guilt: development of the Self-Conscious Affect and Attribution Inventory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59(1):102–11. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.59.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Janoff-Bulman R. Characterological versus behavioral self-blame: Inquiries into depression and rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1979;37(10):1798–1809. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.37.10.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Riessman CK. Stigma and Everyday Resistance Practices: Childless Women in South India. Gender & Society. 2000;14(1):111–135. doi: 10.1177/089124300014001007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holwerda N, et al. Do patients trust their physician? The role of attachment style in the patient-physician relationship within one year after a cancer diagnosis. Acta Oncologica. 2013;52(1):110–117. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.689856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hillen MA, de Haes HCJM, Smets EMA. Cancer patients’ trust in their physician—a review. Psycho-Oncology. 2011;20(3):227–241. doi: 10.1002/pon.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamann HA, et al. Clinician perceptions of care difficulty, quality of life, and symptom reports for lung cancer patients: Results from the ECOG SOAPP study (E2Z02) Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(15 suppl):9102. doi: 10.1097/01.JTO.0000437501.83763.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morse D, Edwardsen E, Gordon HS. Missed opportunities for interval empathy in lung cancer communication. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2008;168(17):1853–1858. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.17.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Leventhal H, Brissette I, Leventhal EA. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In: Cameron LD, Leventhal H, editors. The Self-Regulation of Health and Illness Behavior. Routledge; New York: 2003. pp. 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Croom AR, et al. Illness perceptions matter: Understanding quality of life and advanced illness behaviors in female patients with late-stage cancer. doi: 10.12788/j.suponc.0014. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Llewellyn CD, McGurk M, Weinman J. Illness and treatment beliefs in head and neck cancer: is Leventhal’s common sense model a useful framework for determining changes in outcomes over time? Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2007;63(1):17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Milbury K, Badr H, Carmack C. The Role of Blame in the Psychosocial Adjustment of Couples Coping with Lung Cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2012;44(3):331–340. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9402-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Salander P. Attributions of lung cancer: my own illness is hardly caused by smoking. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16(6):587–592. doi: 10.1002/pon.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Festinger LA. A theory of cognitive dissonance. Row, Peterson; Evanston, IL: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Salander P, Windahl G. Does ‘denial’really cover our everyday experiences in clinical oncology? A critical view from a psychoanalytic perspective on the use of ‘denial’. British journal of medical psychology. 1999;72(2):267–279. doi: 10.1348/000711299159899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Newport F. Seven in 10 Americans Are Very or Moderately Religious. Gallup Press; 2012. [February 20, 2013]. State of the States, Available from: http://www.gallup.com/poll/159050/seven-americans-moderately-religious.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Minkler M. Personal Responsibility for Health? A Review of the Arguments and the Evidence at Century’s End. Health Education & Behavior. 1999;26(1):121–141. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lawson V. Geographies of Care and Responsibility. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2007;97(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8306.2007.00520.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nurit Guttman WHR. On Being Responsible: Ethical Issues in Appeals to Personal Responsibility in Health Campaigns. Journal of Health Communication. 2001;6(2):117–136. doi: 10.1080/10810730116864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sengupta S, et al. HIV Interventions to Reduce HIV/AIDS Stigma: A Systematic Review. AIDS and Behavior. 2011;15(6):1075–1087. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9847-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. [12/14/ 2013];No One Deserves to Die. Available from: http://www.noonedeservestodie.org/

- 82.Luoma JB, et al. Reducing self-stigma in substance abuse through acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, manual development, and pilot outcomes. Addiction Research & Theory. 2008;16(2):149–165. doi: 10.1080/16066350701850295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fledderus M, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy as guided self-help for psychological distress and positive mental health: a randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(03):485–495. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Luoma JB, et al. Slow and steady wins the race: A randomized clinical trial of acceptance and commitment therapy targeting shame in substance use disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(1):43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0026070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Orsillo SM, Batten SV. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Behavior Modification. 2005;29(1):95–129. doi: 10.1177/0145445504270876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]