Abstract

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is characterized by a partial or total insufficiency of insulin. The premiere animal model of autoimmune T cell-mediated T1D is the NOD mouse. A dominant negative mutation in the mouse insulin 2 gene (Ins2Akita) produces a severe insulin deficiency syndrome without autoimmune involvement, as do a variety of transgenes overexpressed in beta cells. Pharmacologically-induced T1D (without autoimmunity) elicted by alloxan or streptozotocin at high doses can generate hyperglycemia in almost any strain of mouse by direct toxicity. Multiple low doses of streptozotocin combine direct beta cell toxicity with local inflammation to elicit T1D in a male sex-specific fashion. A summary of protocols relevant to the management of these different mouse models will be covered in this overview.

Keywords: mice, NOD, diabetes, alloxan, streptozotocin, beta cells

INTRODUCTION

The inbred mouse currently represents the premiere experimental model for analyzing the genetics and pathophysiology of Type 1 diabetes (T1D). T1D in humans is a genetically complex, heterogeneous disease with the pathognomonic feature of a relative or absolute deficiency of insulin producing chronically elevated fasting and fed blood glucose concentrations. This genetic complexity is reflected by the variety of mouse models available. Two spontaneous T1D models will be discussed (the NOD mouse and mice with the dominant negative Insulin2Akita gene mutation, the so-called Akita mouse). The induced models to be covered include mice rendered chemically diabetic by treatment with the beta cell toxins alloxan and streptozotocin. A few of the many examples of transgene-induced beta cell failure will be provided. A brief discussion of virally-induced T1D will also be presented.

THE NOD MOUSE

I. Strain Description

NOD is the descriptor for Nonobese Diabetic, an inbred albino strain derived from Jcl:ICR mice by Makino in Japan (Makino et al., 1980). As reviewed previously (Leiter and Atkinson, 1998), NOD mice exhibit a variety of interesting strain characteristics and susceptibility to multiple organ-specific pathologies in addition to autoimmune pancreatic beta cell destruction. These pathologies reflect multiple defects in regulatory pathways in both the innate and acquired immune systems and include sialitis, thyroiditis, neuritis and, if spared an early death from T1D, high cancer susceptibility (generally to thymic lymphomas). Fortunately, the strain exhibits early sexual maturation with females producing very large litters and exhibiting excellent maternal nurturing. The initiation of autoimmune diabetes, reflected by leukocytic infiltrates into the pancreatic islets (insulitis) occurs in the peri-weaning period in females (2–4 weeks) and slightly later in males (5–7 weeks). In a specific pathogen-free (SPF) colony of NOD/ShiLtJ mice at The Jackson Laboratory, T1D incidence by 30 weeks of age is typically between 90–100% in females and 50–80% in males. It is important for colony management to recognize that development of autoimmunity and clinical diabetes represents a “default” mode in that diabetes can be circumvented in NOD mice exposed to any of a battery of environmental microbial factors normally excluded from SPF vivaria. Indeed, T1D development in NOD mice is an excellent illustration of the “hygiene hypothesis” that postulates early exposure to allergens and microbial antigens is essential to normal development of immune tolerance to self-antigens(Leiter, 1990). Indeed, evidence indicates that hypofunctional NOD antigen presenting cells (APC) fail to drive autoreactive T cells to the stimulation threshold required to trigger their deletion by activation-induced cell death (Driver et al., 2011)].

II. Pathophysiology and Immunopathology

Insulitis in NOD mice represents a mixture of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, B lymphocytes, and variable numbers of macrophages/dendritic cells (MØ/DC). MØ/DC and B lymphocytes appear to be the earliest entrants into the islets, but cytopathic CD8+ T cells with multiple antigenic specificities can be isolated from NOD pancreas as early as 3 weeks post-partum (DiLorenzo et al., 2002). The initial attack is beta cell-specific (Lennon et al., 2009); between the onset of early insulitis and the appearance of clinical symptoms (chronic hyperglycemia), the islets undergo a compensatory response (islet size increase) that, in NOD/ShiLt females, was reflected by normal or near-normal pancreatic insulin content out to 12 weeks of age despite extensive insulitis in many of the pancreatic islets (Gaskins et al., 1992). After this time, compensation [both at the endocrinologic and immunologic level (e.g., regulatory T cells)] is abrogated, as reflected by decreases in first phase insulin release (Ize-Ludlow et al., 2011), pancreatic insulin content and beta cell numbers (Gaskins et al., 1992), as well as impaired glucose tolerance, presaging onset of clinical diabetes. Indeed, failure of a glucose tolerance test (GTT) by normoglycemic NOD mice older than 12 weeks of age is a useful means for staging incipient diabetes (i.e., individuals approaching “end-stage” insulitis, the point where over 80% of beta cells have been destroyed) (Ize-Ludlow et al., 2011). The appearance of anti-insulin antibodies (IAA) in NOD mice marks a late stage in insulitic erosion of the beta cell mass and thus also marks incipient diabetes (Serreze et al., 2011).

Adoptive transfer of various lymphocyte populations into immunodeficient NOD stocks or young preweaning recipients has been the method of choice for analyzing the pathogenic or protective contributions of particular subsets. The most frequently used lymphocyte deficient stocks include the NOD-Prkdcscid (SCID) and NOD-Rag1null (RAG) congenic strains. Interestingly, the even more severely immunocompromised NOD-SCID or NOD-RAG stocks also carrying a targeted X-linked IL-2 receptor common gamma chain gene(denoted NOD-NSG or NOD-NRG respectively), are not suitable for adoptive transfer of diabetes (author, personal observation). This is unfortunate because aging NOD-SCID and NOD-RAG stocks develop very high incidences of pre T-cell and B-cell lymphomas respectively (Shultz et al., 2000) whereas the NSG stock remains lymphoma-resistant. Adoptive transfer of purified populations of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from young, prediabetic NOD donors confirmed the requirement for both subsets (and MHC class I expression on beta cells) in the natural progression of the disease (Christianson et al., 1993). However, if the donor is either diabetic or an incipient diabetic, or pre-activated CD4+ islet-reactive T cell clones are used, the requirement for CD8+ T-effectors (and expression of MHC class I antigens on beta cell targets) is by-passed (Serreze et al., 1997). CD4+ T cell clones reactive against insulin B chain, glutamic acid decarboxylase, islet amyloid polypeptide, and chromogranin A peptides have been isolated from NOD islets or spleen (Haskins and Cooke, 2011). CD8+ clones reactive against insulin B chain, glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit related protein (IGRP), and dystrophiamyotonica kinase have been isolated from NOD islets (DiLorenzo, 2011). Intramolecular and intermolecular antigenic epitope spreading occurs with advancing age and insulitis progression. Developmentally, immune tolerance to insulin is assumed to occur by presentation of insulin peptides by tolerogenic thymic DC. Abrogation of thymic Ins2 expression by gene targeting drastically accelerates T1D onset (Babaya et al., 2006). The finding that B-lymphocyte-deficient NOD mice rarely develop T1D shows that this subset also exerts major influence through their role in presenting soluble antigens (Serreze et al., 1998). Inhibition of adoptively transferred T1D in immunodeficient NOD recipients is typically used to assess (by dose titration with diabetogenic effectors) the function of T-regulatory cells, including CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ “T-regs” as well as CD4+ NKT cells (Chatenoud and Bach, 2005; Driver et al., 2010).

III. Immunogenetics

Almost every chromosome of the NOD mouse has been found to contain at least one gene, and usually more, that affect T1D development. As will be discussed in Protocols, this presents issues when introducing genomic segments from T1D-resistant strains. A review listing certain loci effecting development of hyperglycemia, insulitis, or both, as well as immunophenotypes associated with these “Idd” (Insulin dependent diabetes) loci, has recently been published (Driver et al., 2011). Illustrative of the genetic complexity is the diabetogenicH2g7 Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) on Chromosome (Chr.) 17. NOD H2-Ea and H2-Ab alleles in the MHC class II region, although not particularly rare among ICR-derived mouse strains, both combine to confer susceptibility. Given the recognized role of MHC class I-restricted CD8+ T cells in beta cell destruction, it is not surprising that the NOD MHC class I molecules, although also not uncommon, are also key contributors to the diabetogenicity of the H2g7 complex. Loci that interact with MHC class I or class II influence their antigen presenting functions, such as the beta-2 microglobulin (B2m) gene on Chr. 2, also are critical determinants of susceptibility (Hamilton-Williams et al., 2001), The overall MHC contribution to susceptibility appears recessive in the sense that heterozygous combination (by outcross) with an unrelated MHC completely abrogates NOD diabetogenesis. Whereas specific MHC genes in both humans and NOD mice represent the primary contributors to T1D susceptibility, heterozygosity for certain haplotypes promotes rather than suppresses T1D in humans. With regard to the large numbers of NOD non-MHC genes required for diabetogenesis, very few seem to represent rare mutations unique to NOD. Indeed, most seem to be common or relatively common alleles present in unfavorable combinations with the H2g7 complex. This is illustrated both by the NOD alleles for the B2m (Chr. 2) and Interleukin-2 (Il2) (Chr. 3) genes respectively represent Idd13 and Idd3 disease susceptibility variants (Hamilton-Williams et al., 2001; Yamanouchi et al., 2007). As was noted above, interaction between the genes contributing to susceptibility and the dietary and microbial environment is a major determinant of T1D development in this strain.

IV. Control Strains for NOD

As noted above, NOD mice arose from outbred Jcl:ICR mice. Diabetes-resistant inbred strains independently derived from outbred ICR mice are available. ICR/HaJ mice at The Jackson Laboratory express the NOD H2g7 haplotype, but are strongly diabetes resistant due to differences at numerous non-MHC Idd loci. Another excellent T1D-resistant control stock is NOR/LtJ, a recombinant congenic H2g7 expressing stock containing approximately 88% of its genome from NOD (Serreze et al., 1994). Another ICR inbred strain, ALR/LtJ, selected for resistance to free radical (alloxan)-induced diabetes, expresses a H2g7-like MHC (H2gx) (Mathews et al., 2003). NON/LtJ represents a “sister” strain, sharing the same progenitors with NOD for 5 generations of selection in Japan (Serreze et al., 1994). However, these mice have a disparate MHC and males develop a metabolic syndrome (Makino et al., 1980). For normative physiology/endocrinology phenotypes not involving the adaptive immune system, the T1D-free NOD-SCID or NOD-RAG mice may be used. Further, the Type 1 Diabetes Repository at The Jackson Laboratory (http://type1diabetes.jax.org/holdings.html) maintains a large collection of transgenic, and gene targeted stocks on the NOD background and useful as controls for specific investigations.

THE AKITA MOUSE: A MODEL OF INSULIN-RESPONSIVE DIABETES WITHOUT INSULITIS

Ins2Akita denotes a spontaneous autosomal dominant mutation on Chr. 7 first discovered in a colony of C57BL/6N mice in Akita, Japan (Yoshioka et al., 1997 (Wang et al., 1999; Yoshioka et al., 1997). It was originally called Mody4 because of its dominant mode of inheritance coupled with early juvenile onset of hyperglycemia resembled Maturity Onset of Diabetes in the Young (MODY) in humans. The mutation is a missense change at residue 96 converting a cysteine codon (TGC) to a tyrosine (TAC) codon at residue A7 of preproinsulin II. The consequence of this change is an inability to form a disulfide bridge with the corresponding cysteine residue at B7, and thus, defective protein folding and the induction of an unfolded protein response; i.e.; endoplasmic reticulum stress and induction of beta cell apoptosis. Because of high early mortality in homozygous mutants, the mutation is most commonly studied in heterozygotes. To avoid the complications of diabetic pregnancies, wildtype females are usually mated to young, heterozygous mutant males to produce litters with a 50:50 ratio of mutants and wildtype controls. Regardless of the inbred strain background on which this mutation is studied, hyperglycemia develops in both sexes at weaning. Figure 1 illustrates the early diminution of insulin content in islets from young Ins2Akita heterozygotes versus wildtype mice. Typically, diabetes is more severe and beta cell loss is more extensive in Ins2Akita heterozygous males than in females. As the mutant mice age, beta cell mass decreases concomitant with reduced plasma and pancreatic insulin content. However, a percentage of the beta cells remaining in the residual islets can usually be detected by insulin staining. In surviving Ins2Akita heterozygotes beta cells, insulin molecules made from the two normal Ins1 alleles on Chr. 19, and the one normal Ins2 allele on Chr. 7 allow chronically hyperglycemic mice of both sexes to survive beyond 6 months of age without daily injections of insulin. Indeed, on certain inbred strain backgrounds, residual insulin secretion and other compensatory changes with continued aging may reduce glycemic levels toward normal (Table 1). That the mice remain highly responsive to exogenous insulin therapy was demonstrated by reversal of hyperglycemia by implanting relatively small numbers of syngeneic islets (Mathews et al., 2002). This ability for severely hyperglycemic mice to survive long-term without daily insulin treatment (due to retention of small numbers of beta cells) distinguishes this model from the NOD model. Diabetic NOD mice require daily insulin injections to survive once diabetes is established, and, unlike the Ins2Akita mouse, syngeneic islet transplants are rapidly rejected by the autoimmune process that destroyed the endogenous beta cells. Thus, it has been difficult to maintain aging colonies of diabetic NOD mice for the study of diabetic complications development.

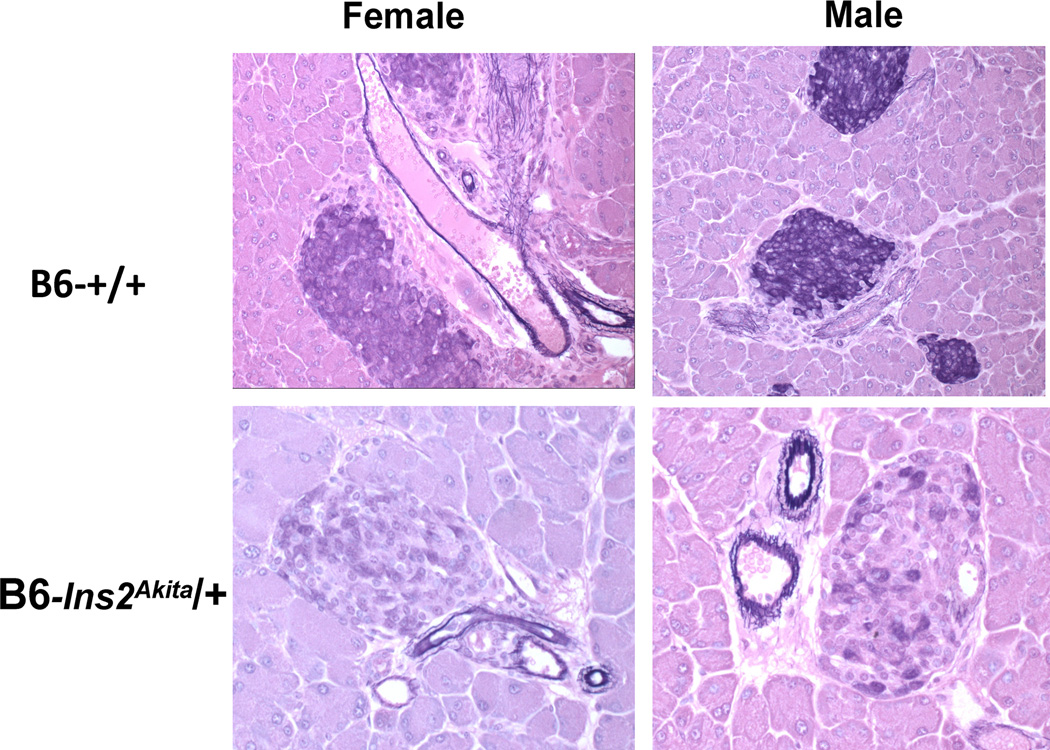

Figure 1.

Histologic appearance of pancreatic islets in 5 to 6-week-old C57BL/6 wildtype control (+/+) and heterozygous Ins2Akita mice of both sexes. Insulin containing beta cells are stained with aldehyde fuchsin (blue color). Note the beta cell degranulation (loss of staining) in mutant mice of both sexes. At the time of necropsy, both mutant mice were hyperglycemic. At later ages, islets from severely hyperglycemic males are almost completely degranulated and markedly reduced in number; mutant females show a similar reduction in islet number, but more residual insulin-positive beta cells per islet.

Table I.

Diabetic Phenotype of Ins2Akita Heterozygous Mice on Different Strain Backgrounds1

| Strain Background | JAX# | Phenotype at six months (Plasma, mean±SE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin♂ | Insulin♀ | Glucose♂ | Glucose♀ | ||

| C57BL/6J | 3548 | 0.20±0.08 | 0.26±0.0.03 | 582±30 | 311±32 |

| FVB/NJ | 6867 | 0.28±0.05 | 0.47±0.05 | 645±28 | 297±26 |

| DBA/2J | 7562 | 0.23±0.08 | 0.67±0.13 | 641±41 | 272±19 |

| 129/Sv | 7688 | 0.65±0.12 | 0.53±0.10 | 505±32 | 415±45 |

Data collected at The Jackson Laboratory for the Diabetes Complications Consortium. Mean plasma insulin (ng/ml) values for wildtype controls of these 4 strains at this timepoint ranged between 2–5 for males and between 0.6–3 for females. Mean control non-fasting glucose values (mg/dl) for these 4 strains ranged between 111–204 for males and 117–191 for females.

The ability to maintain aging colonies of diabetic Ins2Akita mice has permitted assessment of a variety of diabetic complications, including nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy, and cardiomyopathy (Table 2). The mutation has also been combined on the NOD genetic background with targeted Rag1 and Perforin (Prf1) genes with and without the targeted Il2rg(JAX # 14568 and 8659 respectively) such that the diabetic mice are immunodeficient and hence can serve as a vehicle for analyzing beta cell-generating stem cells (Pearson et al., 2008). The mutation is also available on the B6-Rag1 stock (JAX # 4369). A different Ins2C95S dominant negative mutation at the A6 residue and on the C3HeB/FeJ background was generated by ENU (ethylnitrosurea) mutagenesis (Herbach et al., 2007). In addition to the extended survival of heterozygous Ins2Akita diabetic mice without insulin therapy, the model offers the additional advantage over the toxin-induced diabetes models discussed below in avoiding the collateral damage to multiple organ systems that confounds interpretation of diabetes complications development.

Table 2.

Diabetic Complications in B6-Ins2Akita Heterozygous Mice

| Complication | Reference |

|---|---|

| nephropathy | (Brosius et al., 2009; Gurley et al., 2010; Susztak et al., 2006; Yaguchi et al., 2003)) |

| neuropathy | (Choeiri et al., 2005; Yaguchi et al., 2003) |

| retinopathy | (Barber et al., 2005) |

| cardiomyopathy | (Bugger et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2007) |

| reproduction | (Chang et al., 2005) |

EXPERIMENTALLY INDUCED DIABETES: TOXINS

I. High dose alloxan and streptozotocin models

Alloxan (AL) and streptozotocin (STZ) are small molecules that resemble glucose and bind the GLUT-2 glucose transporters in beta cells and liver. Both molecules decompose rapidly in aqueous solution to produce potent free radicals. Because beta cells have relatively weak defenses against oxidative stress(Lenzen et al., 1996), they are especially sensitive to free radical mediated damage. AL generates superoxide and hydroxyl radicals and rapidly induces a necrotic cell death in beta cells of most strains (both sexes) within 48 hours post-injection. Doses between 100–150 mg/kg body weight administered i.p. or i.v.are frequently used to destroy beta cells by direct toxicity, but are probably higher than necessary for most inbred strains, producing unwanted collateral damage, precipitous weight loss, and high mortality if untreated with insulin. Doses of between 50–80 mg/kg are usually effective in producing chronic hyperglycemia, but dosage should be established empirically for any given inbred strain and sex. A literature survey of strains known to be susceptible or resistant to lower AL doses has been published(Leiter et al., 1999). An ED50 of 60 mg/kg or higher has been reported for most inbred strains surveyed (Martinez et al., 1954). A single AL dose of 52 mg/kg i.p. was sufficient to distinguish ALR/LtJ (JAX# 3070), an ICR-derived strain selected in Japan for AL resistance from ALS/LtJ (JAX# 3072), a strain co-selected for sensitivity (Ino et al., 1991). As expected, analysis of the molecular basis for this differential sensitivity showed that ALR mice maintained an unusually high systemic anti-oxidant defense (Mathews et al., 2005). Despite extensive genome sharing including a large portion of the MHC with the autoimmune T1D-prone NOD strain, the ALR strain’s resistance to oxidative free radical damage also rendered their beta cells resistant to killing by NOD beta-cytotoxic T cells in vivo and in vitro (Mathews et al., 2005).

High doses of the fungal antibiotic streptozotocin (STZ) generate highly reactive carbamoylating and alkylating free radicals that attack intercellular proteins and DNA (Wilson and Leiter, 1990). Resultant DNA strand breaks induce poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) that, in turn, exhausts limiting beta cell pools of NADH and elicits apoptosis (Lenzen, 2008). High doses between 150–200 mg/kg body weight i.p. or i.v. produce severe hyperglycemia in both sexes within 48 hours post-administration and subsequent precipitous weight loss and high mortality if untreated with insulin. As is the case for high dose AL, high doses of STZ kill by direct cytotoxicity and elicit collateral damage in multiple cell types (Laguens et al., 1980; Nichols et al., 1981; Szkudelski, 2001).

II. Multiple “Low Dose” STZ Model (MLDSTZ)

In contrast to the high mortality induced by single high doses of either AL or STZ, males of selected inbred strains can be rendered chronically diabetic (mean fasting blood glucose between 300–600 mg/dl) by daily injection i.p. or i.v. of 30–50 mg/kg over a 3–5 day period. Each daily injection kills beta cells by direct cytotoxicity with loss of beta cell mass and insulin secretion being cumulative (Bonnevie-Nielsen et al., 1981). Strains with high (CD-1, NOD/ShiLt, NON/Lt, ALS/Lt, C57BLKS/J, C3H.SW/SnJ, and CBA/J), intermediate (C57BL/6J, C57BL/10J, C3H/HeJ, BALB/cByJ, DBA/2J, and ALR/Lt), and low (FVB/NJ, SWR/J, BALB /cJ, and SWR/J) MLDSTZ sensitivity in males have been identified [reviewed in (Leiter et al., 1999)]. The first report of the MLDSTZ model employed CD-1 males and provided evidence that high sensitivity entailed complementation of direct beta-cytotoxicity with an immune component (e.g., induction of endogenous retroviruses in beta cells followed by a T cell inflammatory infiltration (insulitis) (Like and Rossini, 1976).

The observation of insulitis in some strains, coupled with literature reports of prevention of hyperglycemia by anti-lymphocyte serum in combination with 3-O-methylglucose or other immune manipulations led to the hypothesis that MLDSTZ in males entailed beta cell destruction primarily mediated by autoimmunity engendered against beta cell antigens or neoantigens [reviewed in (Kolb and Kroncke, 1993)]. However, when the MLDSTZ model is compared to the NOD model of spontaneous autoimmune T1D, there are striking differences in addition to the different gender bias (greater female susceptibility in NOD and other autoimmune models, only males susceptible to MLDSTZ). Salient among these are the strict MHC requirement in the NOD model and the ability to adoptively transfer T1D (by NOD lymphocytes) to recipients expressing the diabetogenic H2g7 MHC haplotype. In MLDSTZ experiments, immune transfer of T1D has only been achieved in BALB/cByJ mice whose beta cells transgenically expressed CD80, allowing beta cells to acquire additional antigen presenting capacity not available to non-transgenic beta cells (Harlan et al., 1995). Further arguing against a requirement for autoimmune reactions, syngeneic islet transplants successfully reverse hyperglycemia in MLDSTZ-diabetic males (Leiter, 1987), whereas immune effector memory cells rapidly reject syngeneic islet transplants in spontaneously diabetic NOD recipients. Finally, T-and B-lymphocyte deficient (and innate immunity impaired) NOD-SCID males are highly sensitive to MLDSTZ diabetes (Gerling et al., 1994). Thus, although inflammatory events, including cellular infiltrates associated with MLDSTZ-induced beta cell death, clearly may contribute to further reduction of the beta cell mass, their presence is not obligatory for pathogenesis in susceptible inbred strain males in which >85% of beta cells can be destroyed by direct cytotoxicity.

EXPERIMENTALLY INDUCED DIABETES: KNOCKOUTS AND TRANSGENES

Molecular genetic approaches have generated a multiplicity of mouse models of insulin dependent diabetes without autoimmunity (Terauchi et al., 1995). Such models tend to be male-sex biased and are now too numerous to list in detail here. They include “knockouts” of a variety of genes essential for beta cell function (such as glucokinase, GLUT-2 glucose transporters, etc.) or viability (such as genes associated with the unfolded protein response or with autophagy). Similar diabetic models can be produced by targeting of genes required for insulin signaling and action in other tissues [reviewed in (Lamothe et al., 1998)]. Of particular interest are models wherein genes not normally expressed in beta cells are introduced under the control of insulin promoters, or genes whose expression is native to beta cells but are hyper-expressed. Included among the former molecules are MHC class II and among the latter, MHC class I molecules (Lo et al., 1988; Pujol-Borrell and Bottazzo, 1988). Alternatively, insulin promoter-driven over-expression of genes either native or foreign to the mouse beta cell can produce beta cell failure and early onset hyperglycemia, usually male-biased. Among many examples that could be cited are Type 2 nitric oxide synthase (Takamura et al., 1998), calmodulin(Epstein et al., 1992), cytochrome b5 reductase 4 (Wang et al., 2011), islet specific glucose 6 phosphatase, catalytic subunit-related protein (Shameli et al., 2007), and hen egg lysozyme (Socha et al., 2003). The deleterious effects of many of these transgenic manipulations clearly include endoplasmic reticulum stress and should serve to warm investigators of potential beta cell alterations generated by use of insulin promoters to express high levels of xenogeneic proteins such as bacterial CRE recombinase or jellyfish/firefly fluoroproteins(Lee et al., 2006; Leiter et al., 2007).

EXPERIMENTALLY INDUCED DIABETES: VIRAL INFECTION MODELS

Because of the special facilities required for working with pathogenic viruses, and the availability of numerous non-viral mouse models of T1D, the virally-induced diabetes models are not widely used. The Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus (LCMV) is known to be diabetogenic in males of susceptible inbred strains (Oldstone et al., 1984). Interestingly, NOD is not a susceptible strain; on the contrary, LCMV infection protects them against developing spontaneous autoimmune T1D (Oldstone, 1988). Transgenic expression of LCMV glycoprotein or nucleoprotein antigens in beta cells (RIP-LCMV), does not produce diabetes (Oldstone et al., 1991). However, exogenous administration of the LCMV antigen rapidly elicits a T cell-mediated targeting of the transgenic beta cells and resultant T1D. Such genetically-contrived systems are useful for studying tolerogenic mechanisms for a model antigen, but do not accurately model the immune response directed against multiple innate beta cell antigens seen in the NOD mouse.

Selection for a human beta-cytopathic strain of Coxsackie B4 produced T1D in SJL/J males (Yoon, 1991). However, the major tropism of Coxsackie B4 isolates in mice is to the exocrine pancreas; in NOD mice, protection versus acceleration of T1D is dependent upon the extent of underlying insulitis (Serreze et al., 2005). The M-strain of the Encephalomyocarditis Virus (EMC) also is diabetogenic in males of certain strains, including SJL/J and BALB/cByJ(Craighead, 1975), with diabetogenicity of the D-variant plaque associated with low induction of host interferon gamma (Jordan and Cohen, 1987). Certain rat models of T1D are of particular interest for the study of viruses as diabetogenic triggers. The nominally T1D-resistant BB-DR rat strain can be rapidly turned diabetic by experimental infection with several different types of viruses, including parvovirus and cytomegalovirus (Zipris et al., 2007).

NOTES AND CONCLUSIONS

Protocols for maintaining a NOD colony with high diabetes incidence have been published (Leiter, 1997) and are available online at the Type 1 Diabetes Repository (T1DR) website (http://type1diabetes.jax.org/index.html). This website provides annual T1D incidence for progeny of both sexes produced from breeders protected from T1D by an i.p. injection (hind footpad, 50µl) of complete Freund’s adjuvant at 5 weeks of age. NOD colonies should be monitored annually; a significant drop in T1D frequency in an investigator’s colony from that observed in the supplier’s vivarium may well denote introduction of ancomplicating environmental variable, often a microbial factor. The TIDR website lists a large collection of genetically modified NOD stocks (transgenics, knockouts, congenic lines) available from The Jackson Laboratory. The Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) website (http://www.informatics.jax.org/), contains a wealth of mouse genomic and phenotypic information and links to related resources such as the International Mouse Strain Resource (IMSR, http://www.findmice.org/index.jsp). This resource is a searchable online database for mouse strains, stocks, and ES cell lines available internationally. MGI also links to the Mouse Phenome Database (MPD) that provides a wealth of additional phenotypic data (with protocols) as well as strain genomic comparisons of 36 strains of JAX® mice (phenome.jax.org). Detailed protocols for assessing diabetes and a variety of diabetic complications in both Ins2Akita and Type 2 diabetes models are accessible at the Diabetes Complications Consortium website (https://www.diacomp.org/shared/protocols.aspx) under the Resources & Data section.

With regard to AL and STZ, these reagents should be stored dry and in dessicators as they rapidly degrade in aqueous solution. Hence, each should be used quickly (within 10 minuetes) after hydration either in saline, phosphate buffered saline, or in the case of MLDSTZ, citrate buffer, pH 4.2–4.6, is often used. STZ has been classified as a carcinogen based upon a report of beta cell adenoma development in STZ-treated rats wherein beta cell toxicity was circumvented by co-injection of nicotinamide (Masiello et al., 1984; Yamagami et al., 1985). This has not been repeated in mice, and in humans, STZ has been used clinically as a chemotherapeutic agent to reduce insulinomas (Schott et al., 2000). Hence, care should be taken when weighing and solubilizing both compounds (gloves, face mask) and soiled bedding from mice within 24 hours post-injection should be treated as potentially contaminated and thus, hazardous waste.

To conclude, investigators now have available a large choice of mouse models of T1D, including those spontaneously developing disease with and without autoimmunity (NOD and Ins2Akita respectively) as well as drug-induced (AL and STZ) models and an ever-growing panel of genetically-modified diabetic stocks generated by transgenesis or gene targeting.

Acknowledgments

A portion of the material in this review was supported by NIH contract NO1 DK-7-5000. We thank Drs. Dave Serreze, Leonard Schultz, and Jim Yeadon for their insightful comments and review.

LITERATURE CITED

- Babaya N, Nakayama M, Moriyama H, Gianani R, Still T, Miao D, Yu L, Hutton JC, Eisenbarth GS. A new model of insulin-deficient diabetes: male NOD mice with a single copy of Ins1 and no Ins2. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1222–1228. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber AJ, Antonetti DA, Kern TS, Reiter CE, Soans RS, Krady JK, Levison SW, Gardner TW, Bronson SK. The Ins2Akita mouse as a model of early retinal complications in diabetes. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2005;46:2210–2218. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnevie-Nielsen V, Steffes MW, Lernmark Å. A major loss in islet mass and B-cell function precedes hyperglycemia in mice given multiple low doses of streptozotocin. Diabetes. 1981;30:424–429. doi: 10.2337/diab.30.5.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosius FC, 3rd, Alpers CE, Bottinger EP, Breyer MD, Coffman TM, Gurley SB, Harris RC, Kakoki M, Kretzler M, Leiter EH, Levi M, McIndoe RA, Sharma K, Smithies O, Susztak K, Takahashi N, Takahashi T. Mouse models of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2503–2512. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009070721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugger H, Chen D, Riehle C, Soto J, Theobald HA, Hu XX, Ganesan B, Weimer BC, Abel ED. Tissue-specific remodeling of the mitochondrial proteome in type 1 diabetic akita mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:1986–1997. doi: 10.2337/db09-0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AS, Dale AN, Moley KH. Maternal diabetes adversely affects preovulatory oocyte maturation, development, and granulosa cell apoptosis. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2445–2453. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatenoud L, Bach JF. Regulatory T cells in the control of autoimmune diabetes: the case of the NOD mouse. Int Rev Immunol. 2005;24:247–267. doi: 10.1080/08830180590934994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choeiri C, Hewitt K, Durkin J, Simard CJ, Renaud JM, Messier C. Longitudinal evaluation of memory performance and peripheral neuropathy in the Ins2C96Y Akita mice. Behav Brain Res. 2005;157:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson SW, Shultz LD, Leiter EH. Adoptive transfer of diabetes into immunodeficient NOD-scid/scid mice: relative contributions of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes from diabetic versus prediabetic NOD.NON-Thy-1a donors. Diabetes. 1993;42:44–55. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craighead JE. Animal model of human disease. Mice infected with the M variant of Encephalomyocarditis virus. Am.J. Pathol. 1975;76:537–540. [Google Scholar]

- DiLorenzo TP. Multiple antigens versus single major antigen in type 1 diabetes: arguing for multiple antigens. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27:778–783. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLorenzo TP, Lieberman SM, Takaki T, Honda S, Chapman HD, Santamaria P, Serreze DV, Nathenson SG. During the early prediabetic period in NOD mice, the pathogenic CD8(+) T-cell population comprises multiple antigenic specificities. Clin Immunol. 2002;105:332–341. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver JP, Scheuplein F, Chen YG, Grier AE, Wilson SB, Serreze DV. Invariant natural killer T-cell control of type 1 diabetes: a dendritic cell genetic decision of a silver bullet or Russian roulette. Diabetes. 2010;59:423–432. doi: 10.2337/db09-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver JP, Serreze DV, Chen YG. Mouse models for the study of autoimmune type 1 diabetes: a NOD to similarities and differences to human disease. Seminars in immunopathology. 2011;33:67–87. doi: 10.1007/s00281-010-0204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein PN, Ribar TJ, Decker GL, Yaney G, Means AR. Elevated beta-cell calmodulin produces a unique insulin secretory defect in transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 1992;130:1387–1393. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.3.1371447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerling IC, Freidman H, Greiner DL, Shultz LD, Leiter EH. Multiple low dose streptozotocin-induced diabetes in NOD-scid /scid mice in the absence of functional lymphocytes. Diabetes. 1994;43:433–440. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurley SB, Mach CL, Stegbauer J, Yang J, Snow KP, Hu A, Meyer TW, Coffman TM. Influence of genetic background on albuminuria and kidney injury in Ins2(+/C96Y) (Akita) mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F788–F795. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90515.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton-Williams EE, Serreze DV, Charlton B, Johnson EA, Marron MP, Mullbacher A, Slattery RM. Transgenic rescue implicates β2-microglobulin as a diabetes susceptibility gene in NOD mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:11533–11538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191383798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan DM, Barnett MA, Abe R, Pechhold K, Patterson NB, Gray GS, June CH. Very-low-dose streptozotocin induces diabetes in insulin promoter-mB7-1 transgenic mice. Diabetes. 1995;44:816–823. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.7.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskins K, Cooke A. CD4 T cells and their antigens in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diabetes. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2011;23:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbach N, Rathkolb B, Kemter E, Pichl L, Klaften M, de Angelis MH, Halban PA, Wolf E, Aigner B, Wanke R. Dominant-negative effects of a novel mutated Ins2 allele causes early-onset diabetes and severe beta-cell loss in Munich Ins2C95S mutant mice. Diabetes. 2007;56:1268–1276. doi: 10.2337/db06-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong EG, Jung DY, Ko HJ, Zhang Z, Ma Z, Jun JY, Kim JH, Sumner AD, Vary TC, Gardner TW, Bronson SK, Kim JK. Nonobese, insulin-deficient Ins2Akita mice develop type 2 diabetes phenotypes including insulin resistance and cardiac remodeling. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1687–E1696. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00256.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ino T, Kawamoto Y, Sato K, Nishikawa K, Yamada A, Ishibashi K, Sekiguchi F. Selection of mouse strains showing high and low incidences of alloxan-induced diabetes. Exp. Anim. 1991;40:61–67. doi: 10.1538/expanim1978.40.1_61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ize-Ludlow D, Lightfoot YL, Parker M, Xue S, Wasserfall C, Haller MJ, Schatz D, Becker DJ, Atkinson MA, Mathews CE. Progressive Erosion of {beta}-Cell Function Precedes the Onset of Hyperglycemia in the NOD Mouse Model of Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60:2086–2091. doi: 10.2337/db11-0373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan GW, Cohen SW. Encephalomyocarditis virus-induced diabetes mellitus in mice: model of viral pathogenesis. Rev. Infect. Diseases. 1987;9:917–924. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.5.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H, Kroncke K-D IDDM. Lessons from the low-dose streptozotocin model in mice. Diabetes Review. 1993;1:116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Laguens RP, Candela S, Hernandez RE, Gagliardino JJ. Streptozotocin-induced liver damage in mice. Hormone and metabolic research = Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones et metabolisme. 1980;12:197–201. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-996241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamothe B, Baudry A, Desbois P, Lamotte L, Bucchini D, De Meyts P, Joshi RL. Genetic engineering in mice: impact on insulin signalling and action. The Biochemical journal. 1998;335(Pt 2):193–204. doi: 10.1042/bj3350193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Ristow M, Lin X, White MF, Magnuson MA, Hennighausen L. RIP-Cre revisited, evidence for impairments of pancreatic beta-cell function. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2649–2653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter E. The NOD mouse: a model for insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. In: Coligan JE, Kruisbeek AM, Margulies DM, Shevach EM, Strober W, editors. Current Protocols in Immunology. vol. 3. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1997. pp. 15.19.11–15.19.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter EH. Analysis of differential survival of syngeneic islets transplanted into hyperglycemic C57BL/KsJ versus C57BL/6J mice. Transplantation. 1987;44:401–406. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198709000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter EH. The role of environmental factors in modulating insulin dependent diabetes. In: de Vries R, Cohen I, van Rood J, editors. Current Topics in Immunology and Microbiology. The Role of Microorganisms in Noninfectious Disease. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1990. pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter EH, Atkinson MA. Medical Intelligence Unit. Austin: R.G. Landes Company; 1998. NOD Mice and Related Strains: Research Applications in Diabetes, AIDS, Cancer, and Other Diseases; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter EH, Gerling IC, Flynn JC. Spontaneous insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) in Nonobese Diabetic (NOD) mice: comparisons with experimentally-induced IDDM. In: McNeill JH, editor. Experimental Models of Diabetes. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1999. pp. 257–295. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter EH, Reifsnyder PC, Driver J, Kamdar S, Choisy-Rossi C, Serreze DV, Hara M, Chervonsky A. Unexpected functional consequences of xenogeneic transgene expression in beta cells of NOD mice. Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism. 2007;9 doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00770.x. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon GP, Bettini M, Burton AR, Vincent E, Arnold PY, Santamaria P, Vignali DA. T cell islet accumulation in type 1 diabetes is a tightly regulated, cell-autonomous event. Immunity. 2009;31:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen S. The mechanisms of alloxan- and streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:216–226. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen S, Drinkgern J, Tiedge M. Low antioxidant enzyme gene expression in pancreatic islets compared with various other mouse tissues. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 1996;20:463–466. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)02051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Like AA, Rossini AA. Streptozotocin-induced pancreatic insulitis: new model of diabetes mellitus. Science. 1976;193:415–417. doi: 10.1126/science.180605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo D, Burkly LC, Widera G, Cowing C, Flavell RA, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. Diabetes and tolerance in transgenic mice expressing class II MHC molecules in pancreatic beta cells. Cell. 1988;53:159–168. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90497-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Kunimoto K, Muraoka Y, Mizushima Y, Katagiri K, Tochino Y. Breeding of a non-obese, diabetic strain of mice. Exp. Anim. 1980;29:1–8. doi: 10.1538/expanim1978.29.1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez C, Grande F, Bittner JJ. Alloxan diabetes in different strains of mice. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1954;87:236–238. doi: 10.3181/00379727-87-21345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masiello P, Wollheim CB, Gori Z, Blondel B, Bergamini E. Streptozotocin-induced functioning islet cell tumor in the rat: high frequency of induction and biological properties of the tumor cells. Toxicol Pathol. 1984;12:274–280. doi: 10.1177/019262338401200311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews CE, Graser RT, Bagley RJ, Caldwell JW, Li R, Churchill GA, Serreze DV, Leiter EH. Genetic analysis of resistance to type 1 diabetes in ALR/Lt mice, a NOD-related strain with defenses against autoimmune-mediated diabetogenic stress. Immunogenetics. 2003;55:491–496. doi: 10.1007/s00251-003-0603-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews CE, Langley SH, Leiter EH. New mouse model to study islet transplantation in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Transplantation. 2002;73:1333–1336. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200204270-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews CE, Suarez-Pinzon WL, Baust JJ, Strynadka K, Leiter EH, Rabinovitch A. Mechanisms underlying resistance of pancreatic islets from ALR/Lt mice to cytokine-induced destruction. J Immunol. 2005;175:1248–1256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols WK, Vann LL, Spellman JB. Streptozotocin effects on T lymphocytes and bone marrow cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1981;46:627–632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldstone MB, Nerenber M, Southern P, Price J, Lewicki H. Virus-infection triggers insulin-dependent diabetes-mellitus in a transgenic model— role of anti-self (virus) immuneresponse. cell. 1991;65:319–331. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90165-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldstone MBA. Prevention of type 1 diabetes in Nonobese Diabetic Mice by virus infection. Science. 1988;23:500–502. doi: 10.1126/science.3277269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldstone MBA, Southern P, Rodriguez M, Lampert P. Virus persists in β cells of islets of langerhans and is associated with chemical manifestations of diabetes. Science. 1984;224:1440–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.6203172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson T, Shultz LD, Lief J, Burzenski L, Gott B, Chase T, Foreman O, Rossini AA, Bottino R, Trucco M, Greiner DL. A new immunodeficient hyperglycaemic mouse model based on the Ins2Akita mutation for analyses of human islet and beta stem and progenitor cell function. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1449–1456. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol-Borrell R, Bottazzo GF. Puzzling diabetic transgenic mice. Immunol. Today. 1988;9:303–306. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(88)91322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schott M, Scherbaum WA, Feldkamp J. [Drug therapy of endocrine neoplasms. Part II: Malignant gastrinomas, insulinomas, glucagonomas, carcinoids and other tumors] Med Klin (Munich) 2000;95:81–84. doi: 10.1007/BF03044988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serreze DV, Chapman HC, Gerling IC, Leiter EH, Shultz LD. Initiation of autoimmune diabetes in NOD/Lt mice is MHC class I-dependent. J. Immunol. 1997;158:3978–3986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serreze DV, Chapman HD, Niens M, Dunn R, Kehry MR, Driver JP, Haller M, Wasserfall C, Atkinson MA. Loss of intra-islet CD20 expression may complicate efficacy of B-cell- directed type 1 diabetes therapies. Diabetes. 2011;60:2914–2921. doi: 10.2337/db11-0705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serreze DV, Fleming SA, Chapman HD, Richard SD, Leiter EH, Tisch RM. Blymphocytes are critical antigen presenting cells for the initiation of T cell mediated autoimmune insulin dependent diabetes in NOD mice. J. Immunol. 1998;161:3912–3918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serreze DV, Prochazka M, Reifsnyder PC, Bridgett MM, Leiter EH. Use of recombinant congenic and congenic strains of NOD mice to identify a new insulin dependent diabetes resistance gene. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:1553–1558. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serreze DV, Wasserfall C, Ottendorfer EW, Stalvey M, Pierce MA, Gauntt C, O'Donnell B, Flanagan JB, Campbell-Thompson M, Ellis TM, Atkinson MA. Diabetes acceleration or prevention by a coxsackievirus B4 infection: critical requirements for both interleukin-4 and gamma interferon. J Virol. 2005;79:1045–1052. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.1045-1052.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shameli A, Yamanouchi J, Thiessen S, Santamaria P. Endoplasmic reticulum stress caused by overexpression of islet-specific glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit-related protein in pancreatic Beta-cells. Rev Diabet Stud. 2007;4:25–32. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2007.4.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz LD, Lang PA, Christianson SW, Gott B, Lyons B, Umeda S, Leiter E, Hesselton R, Wagar EJ, Leif JH, Kollet O, Lapidot T, Greiner DL. NOD/LtSz-Rag1(null) mice: An immunodeficient and radioresistant model for engraftment of human hematolymphoid cells, HIV infection, and adoptive transfer of NOD mouse diabetogenic T cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:2496–2507. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socha L, Silva D, Lesage S, Goodnow C, Petrovsky N. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in nonimmune diabetes: NOD.k iHEL, a novel model of beta cell death. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1005:178–183. doi: 10.1196/annals.1288.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susztak K, Raff AC, Schiffer M, Bottinger EP. Glucose-induced reactive oxygen species cause apoptosis of podocytes and podocyte depletion at the onset of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes. 2006;55:225–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szkudelski T. The mechanism of alloxan and streptozotocin action in B cells of the rat pancreas. Physiol Res. 2001;50:537–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamura T, Kato I, Kimura N, Nakazawa T, Yonekura H, Takasawa S, Okamoto H. Transgenic mice overexpressing type 2 nitric-oxide synthase in pancreatic beta cells develop insulin-dependent diabetes without insulitis. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:2493–2496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2493. issn: 0021-9258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terauchi Y, Sakura H, Yasuda K, Iwamoto K, Takahashi N, Ito K, Kasai H, Suzuki H, Ueda O, Kamada N, et al. Pancreatic beta-cell-specific targeted disruption of glucokinase gene. Diabetes mellitus due to defective insulin secretion to glucose. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1995;270:30253–30256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Takeuchi T, Tanaka S, Kubo SK, Kayo T, Lu D, Takata K, Koizumi A, Izumi T. A mutation in the insulin 2 gene induces diabetes with severe pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction in the Mody mouse. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:27–37. doi: 10.1172/JCI4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Guo Y, Xu M, Huang HH, Novikova L, Larade K, Jiang ZG, Thayer TC, Frontera JR, Aires D, Ding H, Turk J, Mathews CE, Bunn HF, Stehno-Bittel L, Zhu H. Development of diabetes in lean Ncb5or-null mice is associated with manifestations of endoplasmic reticulum and oxidative stress in beta cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GL, Leiter EH. Streptozotocin interactions with pancreatic β cells and the induction of insulin dependent diabetes. In: Dyrberg T, editor. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunobiology. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1990. pp. 27–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaguchi M, Nagashima K, Izumi T, Okamoto K. Neuropathological study of C57BL/6Akita mouse, type 2 diabetic model: enhanced expression of alphaB-crystallin in oligodendrocytes. Neuropathology. 2003;23:44–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2003.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamagami T, Miwa A, Takasawa S, Yamamoto H, Okamoto H. Induction of rat pancreatic B-cell tumors by the combined administration of streptozotocin or alloxan and poly(adenosine diphosphate ribose) synthetase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 1985;45:1845–1849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanouchi J, Rainbow D, Serra P, Howlett S, Hunter K, Garner VE, Gonzalez-Munoz A, Clark J, Veijola R, Cubbon R, Chen SL, Rosa R, Cumiskey AM, Serreze DV, Gregory S, Rogers J, Lyons PA, Healy B, Smink LJ, Todd JA, Peterson LB, Wicker LS, Santamaria P. Interleukin-2 gene variation impairs regulatory T cell function and causes autoimmunity. Nature Genetics. 2007;39:329–337. doi: 10.1038/ng1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J-W. Role of viruses in the pathogenesis of IDDM. Ann. Med. 1991;23:437–445. doi: 10.3109/07853899109148087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka M, Kayo T, Ikeda T, Koizumi A. A novel locus, MODY4, distal to D7MIT189 on Chromosome-7 determines early-onset NIDDM in nonobese C57BL/6 (AKITA) mutant mice. Diabetes. 1997;46:887–894. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipris D, Lien E, Nair A, Xie JX, Greiner DL, Mordes JP, Rossini AA. TLR9-signaling pathways are involved in Kilham rat virus-induced autoimmune diabetes in the biobreeding diabetes-resistant rat. J Immunol. 2007;178:693–701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]