Abstract

A goal of HIV-1 vaccine development is to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies (BnAbs), but current immunization strategies fail to induce BnAbs, and for unknown reasons, often induce non-neutralizing Abs instead. To explore potential host genetic contributions controlling Ab responses to the HIV-1 Envelope (Env), we have used congenic strains to identify a critical role for MHC class II restriction in modulating Ab responses to the membrane proximal external region (MPER) of gp41, a key vaccine target. Immunized H-2d-congenic strains had more rapid, sustained, and elevated MPER+ Ab titers than those bearing other haplotypes, regardless of immunogen, adjuvant, or prime/boost regimen used, including formulations designed to provide T-cell help. H-2d restricted MPER+ serum Ab responses depended on CD4 TH interactions with Class II (as revealed in immunized intra-H-2d/b congenic or CD154-/- H-2d strains, and by selective abrogation of MPER re-stimulated, H-2d-restricted primed splenocytes by Class II-blocking Abs), and failed to neutralize HIV-1 in the TZM-b/l neutralization assay, coinciding with lack of specificity for an aspartate residue in the neutralization core of BnAb 2F5. Unexpectedly, H-2d restricted MPER+ responses functionally mapped to a core TH epitope partially overlapping the 2F5/z13/4E10 BnAb epitopes as well as non-neutralizing B-cell/Ab binding residues. We propose that Class II-restriction contributes to the general heterogeneity of non- neutralizing gp41 responses induced by Env. Moreover, the proximity of TH and B-cell epitopes in this restriction may have to be considered in re-designing minimal MPER immunogens aimed at exclusively binding BnAb epitopes and triggering MPER+ BnAbs.

Abbreviations used: HIV-1, Env, MPER, BnAbs, 2F5, Immunogen

Introduction

An efficacious, protective HIV-1 vaccine will likely require the robust induction of Abs capable of neutralizing a wide array of HIV-1 isolates i.e., broadly neutralizing antibodies (BnAbs) (1). This notion is corroborated by experiments demonstrating sterilizing protection either upon passive transfer of BnAbs at physiological levels, preceding SHIV challenge in non-human primate (2-4) or via their retroviral transduction in humanized mice, prior to HIV-1 infection (5). Unfortunately, efforts to elicit relevant BnAb titers by vaccination have been unsuccessful. Furthermore, in chronically infected HIV-1 individuals, BnAbs arise in a minority of subjects, typically years after transmission, and/or only transiently (6, 7). In contrast to these rare (subdominant) BnAb responses, robust (dominant) Ab responses to non-neutralizing envelope (Env) HIV-1 epitopes are induced early in HIV-1 infection, followed by varying degrees of strain-specific or limited neutralizing Ab responses (6, 8, 9). Recently, efforts to develop vaccine strategies for inducing BnAbs have been re-invigorated by advances in high- throughput recombinant Ab technology, that has led to the isolation of many novel BnAbs from chronically-infected subjects, and defined new vulnerable Env epitopes for targeting by vaccines (10).

One such vaccine target is the membrane proximal external region (MPER) of gp41, a conserved region containing contiguous epitopes of several BnAbs, including 2F5, 4E10, Z13 and 10E8 (11-16). Explanations for the dearth of MPER-specific BnAbs have included limited BnAb epitope accessibility due to topological constraints in the MPER (17-22); reviewed in (23-25). We have recently demonstrated the depletion, inactivation, and/or modification of MPER BnAb epitope+ B-cells via immunological tolerance (26), based on two of the better-studied MPER+ BnAbs, 2F5 and 4E10, exhibiting self-/polyreactivity in vitro (27). Supporting this latter hypothesis are several observations we have made in knockin mice expressing the original (somatically-mutated) 2F5 or 4E10 V(D)J and VJ rearrangements (2F5/4E10 VH × VL KI mice): i) expression of these rearrangements results in profound deletion of BM B-cells expressing them as B-cell receptors (BCRs) (28, 29), akin to other KI models expressing BCRs with high affinities for self-antigens (30-32) ii) residual 2F5/4E10 KI B-cells poorly express, and flux calcium through, their BCRs (28,29,33), thus resembling unresponsive (anergic) B-cells (34, 35), iii) residual anergic B-cells from 2F5 KI mice can be “re-awakened” by a TLR agonist-MPER peptide-liposome conjugate immunogen to produce clinically-relevant serum BnAb titers (36), suggesting immunogen conformation is not limiting to elicitation of pre-existing B-cells expressing BnAbs targeting the 2F5 neutralization epitope, and iv) KI mice expressing germline (unmutated) 2F5 H chains exhibit a developmental blockade at least as early and profound as those carrying the original 2F5 Ab (33,36), suggesting that B-cells in the human pre-immune repertoire express unmutated 2F5 BCRs would be subjected to similar, early tolerance checkpoints.

Although the above-mentioned results in our 2F5 KI model support its physiological relevance to assess how anergic B-cells can be targeted via immunization, it does not address other potentially important contributory factors limiting BnAb induction in normal, outbred animals or in healthy individuals i.e., with polyclonal germline (unmutated) pre-immune repertoires. In this context, vaccination in rhesus macaques, using the same regimen that breaks anergy and triggers robust BnAb responses in 2F5 complete KI mice, induces Abs focused to 2F5's core neutralization epitope DKW (14) but fails to elicit BnAb responses (37) at least partly because vaccine-elicited Abs lack somatic mutations required to either bind lipids (38, 39) or alter Ig framework regions, that may enhance neutralization breadth and potency by increasing flexibility and/or Env binding (40). Furthermore, immunization of BALB/c mice with a similar regimen, aimed at breaking tolerance induces non-neutralizing MPER+ serum IgGs (41) such as mAb 13H11, which lacks lipid reactivity (38,41), has an MPER epitope that only partially overlaps 2F5's (42), and binds the post-fusion six-helix bundle of gp41 (43). Thus, these results reinforce the notion that overcoming B-cell tolerance, although necessary, is not sufficient for overcoming subdominant MPER+ BnAb responses to immunization, and that other contributory factors are involved. One such factor may be activation of naïve B-cells that recognize dominant, non-neutralizing MPER epitopes by existing immunogens in preference to those recognizing subdominant BnAb epitopes (9,10,44). This notion is consistent with Ab responses in early HIV-1 infection being predominantly non-neutralizing, gp41 Abs+ (45-47). However, the mechanisms by which such dominant, non-neutralizing MPER+ Ab responses are preferentially triggered is unknown.

In this study, we elucidate a key genetic determinant controlling non-neutralizing Ab responses directed against the 2F5 nominal MPER epitope: MHC class II-restricted TH activation. Unexpectedly, this restriction involves presentation by I-E/I-Ad alleles, to CD4 TH-cells, of a core epitope found in the MPER that overlaps the 2F5/z13/4E10 BnAb epitopes (11,14,16) as well as residues associated with non-neutralizing Ab binding (39,42,48). We propose that this dominant Class II-restricted MPER+ response may contribute to the general heterogeneity of non-neutralizing gp41 responses seen in acute HIV-1 infected patients and vaccinated animals. Furthermore, understanding the collaboration of TH and B-cell epitopes involved in this restriction will likely be critical for engineering gp41 MPER immunogens with modified TH/B-cell epitopes, in order to selectively drive subdominant MPER+ BnAb responses.

Materials and Methods

Immunogen production/formulation, immunizations, and mice

Liposome and/or peptide immunogen components were produced, purified, formulated and used in immunization formulations described below, based on previously described methods (36,37). Briefly, peptide synthesis and purification was performed by CPC scientific (Sunnyvale, CA) and TLR agonist-containing MPER peptide-liposome conjugates were constructed using the adjuvant MPL-A (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL), POPC/POPE/DMPA/CH-containing liposomes, and the 2F5 nominal epitope-containing MPER peptide GTH1-MPER 656 peptide (NEQELLELDKWASLWNWFNITNWLWYIK YKRWIILGLNKIVRMYS), a version of MPER 656 synthesized containing the C-terminal hydrophobic lipid membrane-anchoring tag GTH1 (YKRWIILGLNKIVRMYS).

Female C57BL/6, BALB/c, BALB.B, B10.D2, B10, B10.D2.BR, B10.D2.S, inbred mouse strains were purchased from Charles River Laboratories or the Jackson Laboratory. 2F5 complete (VH+/+ × VL+/+) KI mice were described previously (28). All strains used in this study were 8-12 weeks of age at the start of immunization protocols and housed in the Duke University Animal Facility in a pathogen-free environment with 12h light/dark cycles at 20–25°C under AALAC guidelines and in accordance with all Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Duke University Institutional Biosafety Committee-approved animal protocols. For all immunizations, a minimum of 4 mice per group was used, and single-site injections were administered intra-peritoneally at day 0, week 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10. Prior to immunizations, either purified recombinant JRFL gp140 or MPLA-MPER 656 peptide-liposome conjugates, described above, were formulated in 10% Emulsigen (MVP Technologies, Omaha, NE) and oCpG (Midland Certified Reagent Company, Midland, TX). Placebo immunization groups received 200 μl of 1× saline (for both priming and boosting injections), whereas experimental groups received 200 μl injection volumes of JRFL/Emulsigen/oCpG for priming (corresponding to 25 μg JRFL and 10 μg oCpG), and for most studies unless otherwise noted in the main text, 200 μl injection volumes of MPER 656 peptide-MPLA4-liposome conjugates for boostings (corresponding to 25 μg GTH1-MPER 656 peptide, 10 μg MPLA-4, and 10 μg oCpG). For control TNP immunizations, naïve animals were injected intra- peritoneally with 0.2 ml containing 50 μg the Trinitrophenyl hapten 12-Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin (TNP-KLH, Biosearch Technologies, Novato CA) precipitated in alum in saline. Other adjuvant and peptide/protein immunogen combinations tested in our initial comparisons reported here (Tables 1,2) have been previously described, as detailed in the Table footnotes. For all immunization studies, serum samples were collected 10 days after each immunization and stored at -80°C until further use.

Table 1. Summary of MPER+ serum Ab responses in C57BL/6 & BALB/c mice immunized with various adjuvant + HIV-1 Envelope protein/MPER peptide combinations.

| Immunization Regimen | MPER+ (2F5 nominal epitope-specific) serum Ig endpoint titer ranges1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Route | Prime | Boosts (x4) | C57BL/6 (H-2b) | BALB/c (H-2d) | |

|

|

|

||||

| IM | oCpG | oCpG | - | - | |

| IP | oCpG | oCpG | - | - | |

| IM | Env (CONS)2+RIBI3 | Env (CON-S) + RIBI | - | - | |

| IP | Env (CONS) + RIBI | Env (CON-S) + RIBI | - | - | |

| IM | Env (CONS) +oCpG | Env (CON-S) + oCpG | - | + | |

| IP | Env (CONS) +oCpG | Env (CON-S) + oCpG | - | + | |

| IP | Env (CONS) +oCpG | Env (CON-S) + oCpG | - | ++ | |

| IM | DP178Q16L4 + RIBI | DP178Q16L + RIBI | - | ++ | |

| IP | DP178Q16L + RIBI | DP178Q16L + RIBI | - | ++ | |

| IP | Env (JRFL) + Alum | CGG-DP178Q16L + Alum | - | ++ → +++ | |

| IP | Env (JRFL) + oCpG | CGG-DP178Q16L + oCpG | - | +++ | |

| IP | GTH1-MPER 6564 + oCpG/MPLA | GTH1MPER 656 + oCpG/MPLA | - | ++ → +++ | |

| IM | Env (JRFL) + oCpG | GTH1-MPER 656 + oCpG/MPLA | - | ++ → +++ | |

| IP | Env (JRFL) + oCpG | GTH1-MPER 656 + oCpG/MPLA | - → +/- | ++++ | |

| IM | Env (JRFL) + oCpG | Liposomes5 (with GTH1-MPER 656/MPLA) + oCpG | - → +/- | +++ → +++++ | |

| IP | Env (JRFL)+oCpG | Liposomes (with GTH1-MPER 656/MPLA) + oCpG | - → +/- | +++++ | |

Reciprocal endpoint titer averages of immunization groups (≥4 mice/group) were calculated as previously described (28). Symbols denote the magnitude of Ab responses at peak induction (5th immunizations) as follows: (-) = <102, (-/+) = 102-103, (+) = 103-104, (++) = 104-105, (+++) = 105-106, (++++) = 106-107, (+++++) = >107. Where applicable, arrows denote the observed range across two independent experiments. Data specifically shown for the JRFL prime+MPER liposome boosts (the regimen predominantly used throughout this manuscript) is based on four independent experiments.

Table 2. Summary of MPER+ serum Ab responses to various Env protein/MPER peptide immunogens in MHC haplotype congenic BALB mice.

| Immunization Regimen | MPER+ (2F5 nominal epitope-specific) serum Ig endpoint titer ranges1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Route | Prime | Boosts (x4) | BALB.B (H-2b) | BALB/c (H-2d) | |

|

|

|

||||

| IP | DP178Q16L + oCpG | DP178Q16L + oCpG | - | ++ | |

| IM | Env (JRFL) + oCpG | DP178Q16L + oCpG | - | ++ → +++ | |

| IP | Env (JRFL) + oCpG | DP178Q16L + oCpG | - | +++ | |

| IP | GTH1-MPER 656 + oCpG | GTH1-MPER 656 + oCpG | - | +++ | |

| IP | Env (JRFL) + oCpG | GTH1-MPER 656 + oCpG | - | +++ | |

| IP | Liposomes (with GTH1-MPER 656/MPLA)+oCpG | Liposomes (with GTH1-MPER 656/MPLA) + oCpG | - → + | ++++ | |

| IM | Env (JRFL) + oCpG | Liposomes (with GTH1-MPER 656/MPLA) + oCpG | - → +/- | +++ → +++++ | |

| IP | Env (JRFL) + oCpG | Liposomes (with GTH1-MPER 656/MPLA) + oCpG | - → + | ++++ | |

Data shown was calculated and is denoted the same way as shown for Table 1, and was calculated from two independent experiments.

In vitro re-stimulations and measurements of CD4 TH-cell proliferation, cytokine expression, and activation

Proliferation of primed splenic CD4 TH-cells in response to re-stimulation with MPER peptides was measured either by [3H] incorporation assays of purified CD4 T-cells in the presence of APCs, or by flow cytometry-based detection of BrdU and CFSE incorporation or CD69 expression in splenic CD4 TH-cell. For [3H] incorporation assays, splenic CD4 T-cells (taken 10d after 5th boosts) were purified using a CD4+ T cell Isolation Kit II (Miltenyi Biotec). LPS activated splenocytes (2 days), purified naïve B cells or non-B cells were treated with 50 μg/ml Mitomycin C, washed 3 times with complete RPMI media (RPMI 1640, 10% FCS, β-ME and penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) antibiotics) were used as antigen presenting cells (APCs). CD4 cells (2 × 105/well) were incubated with APCs (8 × 105/well) and/or 5 μM MPER656 peptide in 96-well plates in complete RPMI media, and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 4 days, 1 μCi/well [3H] thymidine (PerkinElmer) were added and incubated for additional 6 hours. Cells were measured for thymidine incorporation using a Micro-β counter (PerkinElmer).

For CFSE dilution and CD69 induction analysis of CD4 T-cell subsets (and total B-cells), primed splenocytes (5-10d post-5th boosts) were collected, red blood cell lysis was performed using ACK Buffer (Life Technologies), and after re-suspension in HBSS with 0.1% BSA at 107 cells/ml, were incubated with 5 μM of CFSE (Life Technologies) at 37°C for 10 min, and immediately quenched using 10 volumes of RPMI-FCS, followed by washing 3× in RPMI-FCS. In vitro re-stimulations were performed by incubating 107/ml CFSE-labeled splenocytes with MPER peptides, and in some cases, superantigens [Staphylococcal Enterotoxin A and B (SEA, SEB), Toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1), Sigma] for indicated periods, using complete RPMI media. T-cell subsets and total B-cells in CFSE-labeled, re-stimulated, primed splenocytes were then fractionated by staining with the Live/Dead Yellow Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kit (Life Technologies). Briefly, cell pellets were washed in PBS, and incubated for 30 min in stain buffer (1% BSA in HBSS) with anti-CD4-PerCPcy5.5 (RM4-5), anti-CD44-APC (IM7), anti-CD62L-PE (MEL-14), anti-CD69-PEcy7 (H1.2F3), anti-CD8-AF700 (53-6.7), and B220-PETexRed (RA3-6B2), all purchased from BD Biosciences. Live T-cell subsets and total B-cells were analyzed using a BD LSR-II (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star). CD69 gating baseline was set based on cells without in vitro peptide stimulation, from naïve (unimmunized) mice. Peptide-specific TH Effector (CD62L-CD44hiCD69+) numbers were calculated by subtracting those re-stimulated with peptide from those that were unstimulated.

Flow staining measurements of IFNγ secretion and BrdU incorporation in CD4 TH effector subsets was performed using a BrdU Flow Kit (BD Biosciences). Briefly, splenocytes (107/ml) 10d post-5th boosts were incubated with MPER 656 peptide in complete RPMI media for 48h. During the last 6h pre- harvest, BrdU and GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) were added to the culture media. Cells were harvested, incubated with the Live/Dead Yellow for 30 min, and washed with PBS. CD4 T-cell subsets were then fractionated by surface staining, as described above. After fixation and permeabilization, cell pellets were digested with DNase and stained with anti-Brdu-V450 (3D4) and anti-IFNγ-APC (XMG1.2) according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences). Peptide-specific TH effector CD4 cells were calculated by determining total numbers of CD62L-CD44hi BrdU+ or CD62L-CD44hi IFNγ+ cells (re-stimulated with peptide, subtracted from background).

MHC blocking Ab analysis and TH epitope mapping

Abs specific for MHC I H-2Dd (34-2-12), H-2Kd (SF1-1.1), or MHC II I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2), I-Ad (AMS-32.1), I-E (14-4-4S), as well as the corresponding isotype controls rat IgG2b (A95-1), mouse IgG2a (G155-178), and mouse IgG2b (MPC-11) were purchased from BD Biosciences. ACK-treated splenocytes were incubated with the above Abs for 1h, followed by MPER 656 peptide stimulation in complete RPMI media at 37°C with 5% CO2 for an additional 16h. Antibody inhibition was calculated by the percentage decrease of CD69+ MPER 656 peptide-specific TH cells, relative to those in the absence of blocking antibodies.

For TH epitope mapping studies, ACK-treated, primed splenocytes from immunized BALB/c (H-2d) or BALB.B (H-2b) mice were incubated with single amino acid overlapping 15-mer MPER peptides spanning gp41 132-159 (as denoted in Fig. 5D) in complete RPMI media at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24h. TH effector and total B-cell from primed splenocytes were then subfractionated by cell surface staining analysis as described above, and the relative ability of peptides to re-stimulate each population was measured by CD69 expression, also as described above. Overlapping peptides were synthesized and purified by CPC scientific (Sunnyvale, CA); to improve solubility, one or two K residues were added to the C termini of MPER peptides spanning the gp41 155-159 region (i.e. TH gp41 156-159). TH gp41-155 could not be synthesized due to solubility issues.

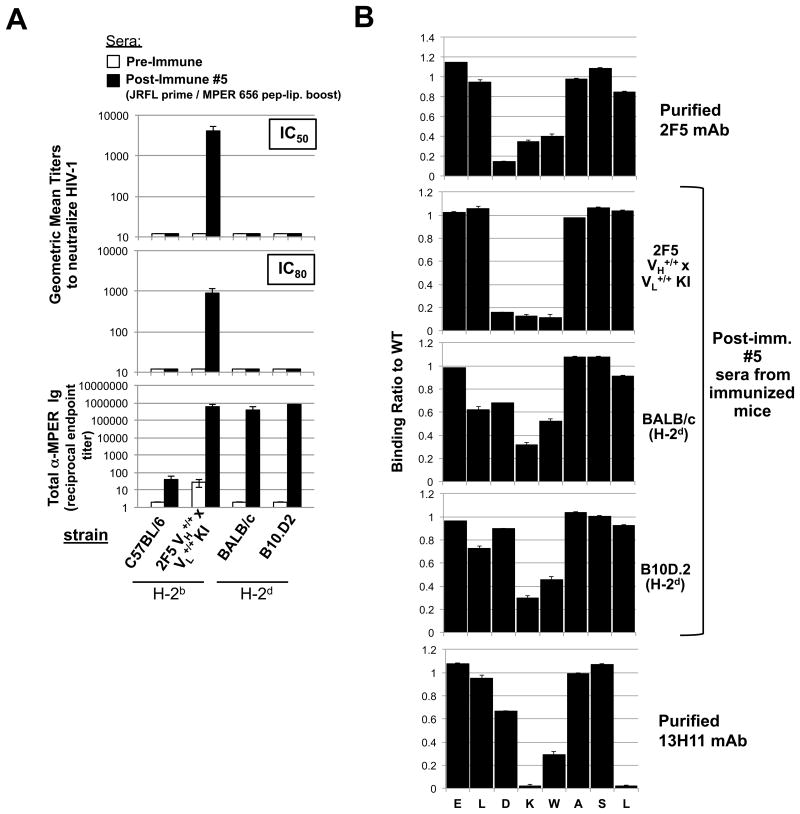

Figure 5. Neutralization activity and MPER epitope specificity of MHC-restricted MPER+ serum Ab responses elicited by vaccination.

A. Serum neutralizing Ab induction in immunized “high responder” (H-2d) congenic B10 and BALB strains was measured at peak MPER+ serum Ig induction (10d after 5th immunizations with experimental (JRFL prime/TLR4/9-MPER peptide-liposome boost) regimen, or as a negative control in pre-immune sera, using the HIV-1 B.MN.3 isolate in the TZM-b/l neutralization assay (28,53). Shown are GMTs of reciprocal dilutions of sera to inhibit HIV-1 B.MN.3 at 50 or 80% levels (top panels) and corresponding MPER (2F5)-specific Ig levels (calculated and represented as in Fig. 1B-C as reciprocal endpoint titer means±SEMs (bottom panel). Data shown uses sera taken from >3 mice/group assayed. For comparison, also shown as controls are the (H-2b) “low-responder” C57BL/6 strain and 2F5 complete KI mice (on the C57BL/6 background). B. SPR epitope mapping of serum taken from immunized “high responder” (H-2d) congenic B10.D2 and BALB/c strains, measured at peak MPER+ serum Ig induction (10d after 5th immunizations with experimental regimen). Shown are SPR sensograms of serum Ab binding to WT or mutant alanine scanning SP62 (2F5 epitope-containing) peptides, represented as normalized binding i.e., ratio between binding responses of sera to the alanine scanning mutant and WT SP62 peptides. As controls for specificity to the 2F5 neutralizing core DKW, also shown are binding profiles of 10 μg/ml purified mAbs 2F5 and 13H11 (upper and lower panels, respectively). All serum Ab binding data shown is representative of measurements of individual samples repeated in two independent experiments using >2 mice/group assayed.

ELISA, Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), and HIV-1 neutralization assays

2F5 epitope-specific MPER-specific serum Ab ELISAs and SPR measurements of mAb or serum interactions with the 2F5 epitope were determined as previously described (28,36,37,39,48). Briefly, ELISA measurements of MPER-specific serum Ab titers were determined using high-binding microtiter plates coated at 0.2 μg/well with the 2F5 nominal epitope-containing peptide SP62 (QQEKNEQELLELDKWASLWN) corresponding to residues 659–678 of the HIV-1 envelope, and SP62-specific total Ig, IgM or IgGs were detected using AP-conjugated anti-mouse kappa, μHC or ″HC-specific reagents, respectively. For SPR assays, the mouse IgG1 anti-gp41 MPER-specific cell line 13H11 was grown and maintained in DMEM media (Life Technologies) containing 10% FCS, 2-ME and penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) antibiotics as previously described (41) and purified m2F5 and 13H11 mAbs were confirmed by running fragments on reducing/non-reducing gels and staining with Coomassie Blue. All SPR measurements of mAb or serum interactions with the gp41 MPER WT or mutant peptides spanning the 2F5 epitope were conducted on a BIAcore 4000 instrument, and data analyses, including affinity measurements, were performed using the BIAevaluation 4.1 software (BIAcore), as previously described (28,36,37,39). TNP-specific serum Ab titers were determined by ELISA using plate-coated TNP-BSA (0.2 μg/well, Biosearch Technologies, Novato CA) and AP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL).

HIV-1 neutralization was determined using the TZM-b/l pseudovirus infectivity assay as previously described (28,53), using the HIV-1 isolate B. MN.3, which we previously showed is a reliable and sensitive method for screening m2F5 IgG neutralization activity in mouse serum (36).

Statistical analysis

Statistics were performed by either Excel (Microsoft) or GraphPad (Prism) software to determine P values by paired student t-test.

Results

MPER-specific serum Ab responses to HIV-1 immunization are MHC haplotype-restricted

We initially observed differences in the magnitude of 2F5 nominal MPER epitope-specific (herein designated MPER+) Ab responses in a series of parallel immunization studies in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mouse strains, using various combinations of adjuvants and HIV-1 immunogens (Table 1). In these studies, BALB/c mice invariably had 2-6 log higher peak MPER+ serum Ab titers than those of C57/BL6 mice, despite variations in peak titers of both strains that depended on adjuvant used (oCpG, Ribi, MPLA, Alum), presence or absence of priming gp140 Env immunogen, or form of MPER immunogen used (peptides or peptide-liposome conjugates). Because we previously reported that the IgHa allotype restricts the degree of naive IgM+ B-cell interactions with the 2F5 nominal epitope (48), we first tested if IgH allotype drives MPER+ Ab responsiveness. We found no significant differences between immunized IgH congenic strains in titers of MPER+ total serum Ig (Fig. S1A) or MPER+ serum IgM and IgG (Fig. S1B), nor in distributions of total serum Ig isotypes and subclasses (Fig. S1C). From these results, we therefore conclude that magnitude and isotypic distribution of MPER-specific Ab responses to Env immunization is not impacted by IgH allotype.

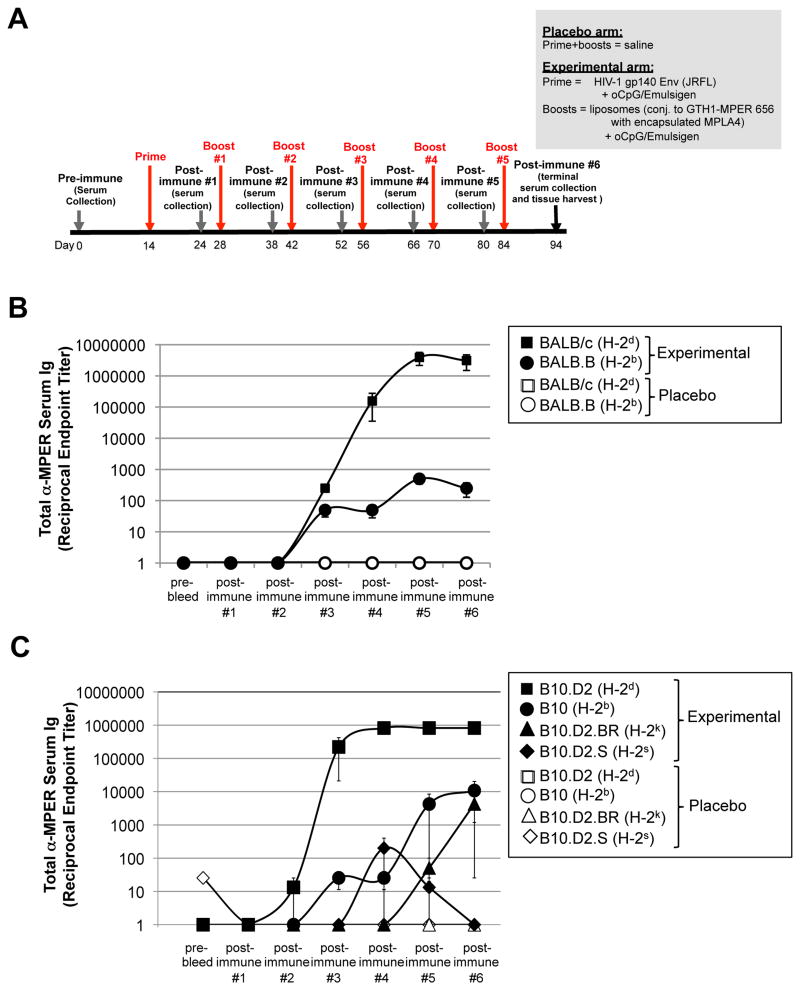

Since we previously noted that several other strains sharing the same MHC haplotype (H-2d) as BALB/c mice also exhibited robust MPER+ serum Ab responses, we formally tested if MHC- restriction was involved in driving the magnitude of MPER+ Abs. To do this, we compared MPER+ serum Ab responses in BALB/c (H-2d) and BALB.B (H-2b) strains (the latter sharing the same haplotytpe as the C57BL/6 “low responders” (Table 1)), immunized with either a placebo (saline) regimen or an experimental regimen (involving priming with gp140 Env, then boosting with a [TLR4/9 agonist-MPER peptide-liposome] conjugate immunogen) (Fig. 1A), a regimen which elicited the highest peak MPER+ serum Ab titers across C57BL/6 and BALB/c strains (Table 1; lower row). As expected, significantly lower titers of MPER+ serum Abs were seen in immunized BALB.B, relative to BALB/c mice (Fig. 1B). As in our comparisons of C57BL/6 (H-2b) and BALB/c (H-2d) strains, the same relative differences in MPER+ Ab magnitude were observed in BALB.B (H-2b), and BALB/c (H-2d) strains, regardless of adjuvant and immunogen combinations used for immunizations (Table 2), but the experimental (JRFL prime/TLR-MPER peptide-liposome boost) regimen again induced the highest peak MPER+ serum Ab titers across both MHC congenic strains (Table 2; lower row). Since this regimen has also been shown to induce robust serum MPER+ Ab titers in 2F5 KI mice (36), as well as MPER+ Ab responses focused on the 2F5 (DKW) neutralizing residues in rhesus macaques (37), and is used in all subsequent immunizations in this study (unless otherwise noted).

Figure 1. MHC-dependent MPER+ Ab responses are observed in two independent series of MHC haplotype congenic mouse strains.

A. Experimental design of immunization studies. Shown are the placebo (saline) and experimental (JRFL prime, [TLR4/9-MPER peptide-liposome] conjugate immunogen boost) arms and the study schedule, including timing of prime/boosts, serum collections, and harvests. Note that because the highest peak MPER+ Ab titers were observed in all strains using the experimental regimen shown (i.e. relative to other adjuvant/immunogen combinations tested; Table 1, 2), it is used in all other results in this study (i.e., unless otherwise noted). B. ELISA measurements of total MPER (2F5 epitope)-specific serum Ig (kappa) responses (mean±SEM) in BALB/c and BALB.B congenic mice, were measured against plate-bound 2F5 nominal epitope-containing peptide SP62, and calculated as reciprocal endpoint titers, as previously described (28) and in the Materials and Methods. Data are shown as mean±SEM reciprocal endpoint titers of individual mouse serum samples at various serum collection time points (using >3 individual mice/time point) during course of immunization protocol. C. ELISA measurements of MPER-specific serum Ig levels in a B10.D2 series of MHC haplotype congenic mice, measured and represented as in Fig. 1B.

Since it has been reported that HIV-1 Env responses to immunization are Th2-polarized (49-52), that we note differential responsiveness in MHC congenic strains on a BALB (Th2) background above demonstrates Th2-related effects cannot exclusively be responsible, but also do not rule out their involvement. To formally exclude this possibility, and to extend our results across several other MHC haplotypes, we immunized a separate series of congenic strains, on a Th1-biased background (B10), bearing H-2d, H-2b and in addition, two other MHC haplotypes, H-2s and H-2k. Only B10.D2 (H-2d) mice had high MPER+ serum Ab responses, whereas those bearing other haplotypes had low or no responses (Fig. 1C). From these experiments, we conclude that in normal mice, MPER+ serum Abs elicited in response to immunization with MPER immunogens are restricted by MHC haplotype, with H-2d specifying more rapid and higher-titers, regardless of regimen used.

H-2d-restricted MPER+ serum Ab responses are MHC classII/TH-dependent and correspond with MPER-specific in vitro activation/proliferation of primed CD4 TH subsets

The fact that serum Abs elicited in BALB/c and B10.D2 “high responder” strains were predominantly IgG (Fig. S1) and were long-lasting, as determined by their persistence several weeks after immunization suggested a requirement for TH-MHC class II interactions in H-2d-restricted MPER+ serum Ab responses. To test this genetically, we examined MPER+ serum Ab responses in MHC H-2d/b intra-congenic B10 strains, i.e. differing in H-2d and H-2b haplotype at class I and II alleles (Fig. 2A). Indeed, MPER+ serum Ab responses in immunized B10.HTG mice (an intra-congenic strain bearing I-Ad/I-Ed class II and Db/Lb class I alleles) were comparable to those in the parental responders (B10.D2), whereas conversely, those in immunized B10.D2-H2 mice (an intra-congenic strain bearing I-Ab/I-Eb class II and Dd/Ld class I alleles) were comparable to MPER+ serum Ab responses in the non-responder (B10) strain (Fig. 2B). While these results strongly suggest involvement of MHC class II-restricted, CD4 T-cells in MPER+ serum Ab responses, they cannot formally rule out a role for the H-2K class I allele, since no H-2d/b intra-congenic linkage strains exist between it and Class II alleles.

Figure 2. MPER+ Ab responses in MHC H-2b/H-2dhaplotype intra-congenic strains.

A. Linkage chart of strains, showing MHC haplotypes at various MHC alleles. B. MPER+ Ab responses in immunized haplotype intra-congenic strains, measured in the same manner as those shown in Fig. 1.

To exclude this possibility, we crossed BALB/c mice to CD154-/- mice (i.e. deficient in expression of CD40L and thus, incapable of responding to cognate CD4 T-cell help) and immunized them with our experimental (JRFL prime, TLR-MPER peptide-liposome boost) regimen. As would be expected if MPER+ Ab responses in MHC (H-2d) responder strains were CD4 TH-dependent, immunized BALB/c × CD154-/- mice had profound reductions in MPER+ serum Ab responses, relative to BALB/c mice on CD154-sufficient backgrounds (Fig. 3A). These reductions were as significant as TNP-specific Ab responses in C57BL/6 (H-2d) and BALB/c (H-2b) mice on CD154-deficient backgrounds, immunized with TNP-KLH (a control immunization to elicit TH-dependent, non MHC haplotype-restricted Ab responses). Furthermore, the higher proportion MPER+ IgG+ B-cells present in MPER-immunized “responder” (H-2d) strains, were also significantly reduced in those on CD154-deficient backgrounds, comparable to reductions in TNP-specific IgG+ B-cells from TNP-KLH-immunized H-2b and H-2d CD154-/- mice (Fig. 3B). Together, these results demonstrate a role for Class II haplotype-specific interactions with CD4 TH epitopes in specifying MPER+ Ab responses.

Figure 3. MPER+ Ab and splenic B-cell responses in the MHC H-2d responder haplotype require cognate CD4 T-cell help.

A. WT or CD154 knockout (CD40L-/-) mice on BALB/c (H-2d) or C57BL/6 (H-2b) backgrounds were immunized with either control (50 μg TNP-KLH plus Alum) or experimental (JRFL/TLR4/9-MPER peptide-liposome boost) regimens, as described in Materials and Methods and Fig. 1, respectively. All control and experimentally immunized groups were measured for both MPER+ and TNP+ Ab responses, as revealed by α-IgG-AP detection of plates coated with the 2F5 nominal epitope peptide SP62 or TNP-BSA, respectively (and as described further in the Materials and Methods section). B. CD154-dependent H-2d-restriction of MPER-specific IgG+ B-cells in immunized mice. Shown are graphical representations of TNP or MPER-specific IgG1+ B-cells/106 total (singlet, live, kappa+ gated) splenic B-cells from BALB/c (H-2d) and C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice (on either CD154-sufficient or deficient backgrounds), immunized with control (TNP-KLH) or experimental (JRFL prime/TLR-MPER peptide-Liposome boost) regimens. For all data shown, splenocytes were taken 10d after 5th immunizations and ≥2 mice/immunization group is shown. MPER-specific B-cells were measured by 2F5 nominal MPER epitope (SP62) tetramers, as previously described (28,44), whereas TNP-specific cells were enumerated by TNP-Fluorescein-AECM-FICOLL as described in the Materials and Methods. Similar differences in total and MPER-specific IgG1+ splenic B-cells were also seen between immunized BALB/c (H-2d) and BALB.B (H-2b) congenic MHC strains on CD154-sufficient backgrounds (data not shown).

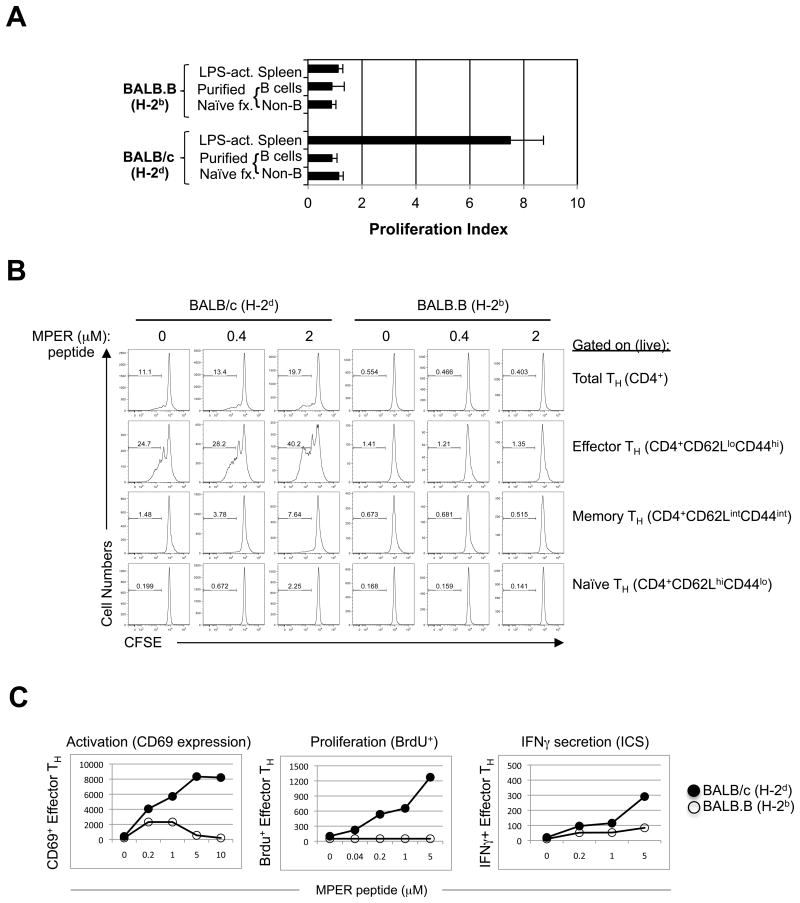

To further characterize the role of MHC class II/TH interactions in MPER+ responses, we examined primed CD4 T cell responses re-stimulated in vitro with MPER (2F5 epitope-containing) peptides. First, we isolated splenocytes from immunized BALB/c (H-2d) and BALB.B (H-2b) mice at peak serum Ab induction, i.e. 5-10d after 4th boosts (Fig. 1B), separated splenic CD4+ T-cells at high purity (Fig. S2A), re-stimulated them in vitro for 4d with MPER peptides in the presence of haplotype- matched accessory cells, and compared their ability to proliferate in 3H incorporation assays. Only H-2d-restricted CD4 T-cells, in the presence of MPER peptides and interestingly, LPS-activated accessory splenocytes, exhibited significant proliferation, suggesting a requirement for activated B-cells as APCs (Fig. 4A). H-2d-restricted proliferation in CD4+ T-cell subsets was then further examined by obtaining total splenocytes from BALB/c and BALB.B mice (also 5-10d after 4th boosts), re-stimulating them in vitro with MPER peptides, and measuring CFSE dilution in CD4 TH naïve, effector, and memory subsets, which were differentiated by gating on surface expression of CD44 and CD62L (L-selectin) by flow cytometry (Fig. S2B). We found that primed CD4+ TH effector (CD44hi, CD62Llo) and memory (CD44int/hi CD62Lint/hi) subsets from H-2d-restricted mice had significantly elevated MPER-specific as well as baseline proliferation (i.e. low CFSE dilution), relative to those from H-2b-restricted mice (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. MPER-dependent CD4 TH activation, proliferation and IFNγ secretion in MHC H-2b and H-2d congenic strains.

A. MPER-induced proliferation of purified CD4 cells from immunized BALB/c and BALB.B mice (taken 10d after 5th immunizations with experimental regimen). In vitro re-stimulations were done using 5 μM of the MPER 656 peptide with the various denoted cell fractions used as APCs, and proliferation was measured by [3H] thymidine incorporation, as described in the Materials and Methods section. The CD4 T-cell proliferation index shown was calculated as the cpm ratio of peptide re-stimulated groups: control (unstimulated) groups. B. MPER-dependent proliferation of CD4 splenic subsets from immunized mice (10d after 5th immunizations with the experimental regimen) was measured by CFSE analysis. Numbers shown represent the percentage of dividing cells (i.e. denoted CFSE low). C. MPER-dependent TH effector activation (CD69 expression), proliferation (BrdU incorporation) and cytokine expression (IFNγ intracellular staining), were measured by flow cytometry. Numbers shown are MPER-induced TH effector CD4 cells/106 total CD4 cells.

As the primed TH effector subset had the highest percentage of peptide-specific, proliferating cells, and were therefore readily trackable, we examined several other well-described functional parameters of proliferation and activation in this subset by flow cytometry, after re-stimulation of primed splenoctyes (taken 4-7d after 4th boosts from both haplotype congenic strains). These included IFN-γ production by intracelluar cytokine staining (ICS), surface expression analysis of the early activation marker CD69, and BrdU incorporation (an additional measure of cell proliferation/turnover), and as expected, all were elevated in MPER peptide-restimulated, primed H-2d restricted TH effector populations, relative to those that were H-2b-restricted (Fig. 4C). Consistent with TH-dependent proliferation/activation of B-cells, increases in the proportion of dividing cells (i.e. having low CFSE incorporation) and CD69 expression by total (CD19+B220+) B-cells from primed, MPER peptide-restimulated H-2d restricted splenocytes was also observed (Fig. S3).

H-2d-restricted MPER+ serum Ab responses are non-neutralizing

To assess if MPER-specific Abs elicited by immunization in “high responder” (H-2d) strains had any detectable HIV-1 neutralizing activity, we compared the ability of serum Abs from immunized BALB/c and B10.D2 mice to neutralize the 2F5-sensitive, Tier 1 HIV-1 isolate B.MN.3 in the TZM-b/l pseudovirus assay (53). As a positive control for neutralization by serum Abs from immunized mice, we used similarly-immunized 2F5 “complete” knock-in (KI) mice, whose B-cells have been engineered to express the VH/VL pair of the original 2F5 mAb (28) and which we have recently shown can generate robust titers of potently-neutralizing MPER+ serum Abs on the B6 (H-2b) background (36). In this system, it is important to point out that equally potent responses can be generated on either CD154 sufficient or deficient backgrounds, consistent with being generated in an exclusively T-independent manner, under conditions where immunodominant non-neutralizing responses are not favored (36). We found that while immunized H-2d congenic strains had peak MPER+ serum Ab titers comparable to those from immunized 2F5 complete KI mice (Fig. 5A; lower panel), they exhibited no significant neutralization activity (Fig. 5A; upper panels).

To determine specificity of H-2d-restricted serum Ab responses, we performed fine specificity mapping of serum samples from immunized BALB/c and B10.D2 strains at their peak induction (after 5th boosts) by surface plasmon resonance analysis. Strikingly, we found that serum Abs had significantly decreased specificity for the aspartate residue in the DKW neutralization core of 2F5 (Fig. 5B). In contrast, serum Abs derived from 2F5 complete KI mice, like the original 2F5 BnAb, exhibited fine specificity for all three neutralization core residues, consistent with potently neutralizing HIV-1 MN. Also noteworthy is that despite their reduced specificity for gp41664 in the DKW neutralization core, serum from H-2d strains, immunized with MPER peptide-liposome conjugates, are more focused to the neutralization core than 13H11, a non-neutralizing mAb which was also derived from BALB/c (H-2d) mice, but which were immunized instead with Env protein (41,43). This likely reflects the general ability of the MPER peptide-liposome immunogen to focus the MPER+ Ab response to the DKW core (37), since MPER epitopes, only when presented in lipids, selectively bind 2F5 and 4E10, i.e. but not 13H11 (38,54).

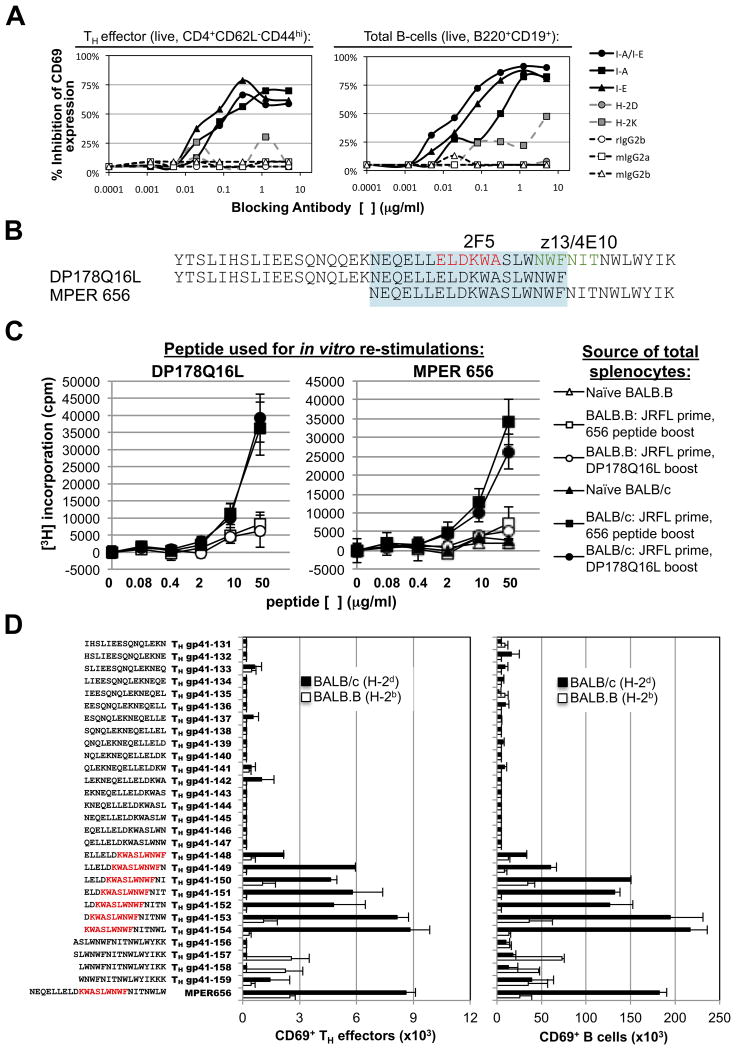

MHC class II haplotype-restricted, MPER-specific CD4 T-cell responses map to the TH epitope KWASLWNWF

To understand the mechanism by which MHC class II-restricts MPER-specific responses, we examined MPER-specific induction of CD69 expression in TH effector CD4+ and total B-cell populations within primed splenocytes from immunized BALB/c (H-2d) responder strain that were re-stimulated overnight with MPER peptides, either alone, or in the presence of various α-H-2 class I, class II, or isotype control Abs (Fig. 6A). As expected, all α-class I Abs minimally inhibited MPER-specific CD69 expression whereas a general α-Class II (i.e., α-I-E/I-A) blocking Ab (as well as Abs specific for I-A or I-E alleles) had a dramatic effect at subsaturating concentrations, indicating a critical role of both Class II alleles in abrogating MPER-specific CD69 expression in TH effector CD4+ and total B-cells (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. MHC class II-restricted MPER responses map to the core TH epitope KWASLWNWF.

A. Inhibition of MPER-dependent activation (CD69 expression) of splenic TH effector CD4 cells or total B-cells by MHC class I or II blocking antibodies. Cells were taken 10d after 5th immunizations, and pooled from five BALB/c mice. Data shown is representative of three independent experiments. B. Overlapping peptides DP178Q16L and MPER 656 were used as immunogens and/or for in vitro re- stimulations. The core neutralizing epitopes of the 2F5 and 4E10 BnAbs are shown in red or green lettering, respectively, while the region to which MPER re-stimulations map are represented in blue shading. Also shown for reference is the SP62 peptide, used for measuring ELISA serum Ig titers in this study. C. MPER peptide-induced proliferation of splenocytes from immunized mice (10d after 5th immunizations) was measured by [3H] thymidine incorporation. Data are shown as mean±SEM of cpm (>3 individual mice). D. TH epitope mapping with overlapping peptides spanning the MPER region. Activation of TH effector CD4 cell or B-cell populations from BALB/c (H-2d) or BALB.B (H-2b) primed splenocytes (pooled from 5 mice/strain), in vitro-stimulated with 5 μM of MPER peptides, was measured by CD69 surface staining. Shown are the numbers (mean±SEM) of CD69+ MPER-activated TH effectors/106 total CD4+ cells (left panel) or CD69+ MPER-activated B cells/106 total (B220+) B-cells (right panel). Sequences of overlapping peptides for mapping are shown to the left, with residues defining the TH core epitope indicated in red letters. Results are representative of two independent experiments.

To examine the region where class II haplotype-restricted MPER responses map, we used a set of overlapping peptide immunogens: DP178Q16L and MPER 656 (spanning N- and C-terminal portions, respectively) of a stretch in the gp41 MPER HR2 region (gp41145-163) overlapping the 2F5, 4E10, and z13 BnAb neutralization epitopes (Fig. 6B). Because these overlapping peptides have been used extensively in our various previous immunization studies (Tables 1, 2), we used them here to immunize BALB/c (H-2d) responders (and as controls, BALB.B (H-2b) non-responders) and then again, to re-stimulate total primed splenoctytes from these mice in order to assess relative proliferation by 3H incorporation. We found that the MPER 656 peptides could re-stimulate DP178Q16L-immunized responder splenocytes, and conversely, that DP178Q16L peptides re-stimulate MPER 656-immunized responder splenocytes (Fig. 6C). These results identified an 18 aa overlapping region (which includes the 2F5 nominal epitope, and also partially overlaps the z13/4E10 epitopes), responsible for MHC-restricted MPER+ responses (Fig. 6C, highlighted region).

We then formally fine-mapped the functional responsiveness of this region using 15-mer peptides, overlapping by single residues spanning the entire 18aa stretch to re-stimulate primed splenocytes from immunized BALB/c responder mice, after which CD4+ TH effector cell activation was measured using CD69 expression as the readout (Fig. 6D, left panel). Using this approach, we identified a specific region (gp41154-163) to which activation localized, thus representing the core TH epitope for H-2d restriction: KWASLWNWF. This same core was observed in the activation (i.e., induction of CD69 surface expression) of primed total (CD19+B220+) B-cells (Fig. 6D, right panel). The KWASLWNWF sequence contains portions of the 2F5 (KWA) and 4E10/z13 (NWF) nominal MPER epitopes ELDKWA and NWF(N/D)IT, respectively (11-16).

Discussion

In this study, we uncover a key genetic determinant impacting MPER (2F5 nominal epitope)-specific IgG Ab titers elicited: MHC class II haplotype restriction of CD4 TH responses. By demonstrating this restriction occurs in immunized MHC congenic strains on both BALB and B10 backgrounds (with Th1 and Th2-polarized responses, respectively), our study excludes effects related to the general Th2-bias of α-Env IgG responses previously noted during HIV-1 infection (55,56), and in HIV-1 vaccination of mice and humans (49-52). Our results also rule out IgH allotypic effects, which we previously demonstrated impact non-paratopic/low-affinity interactions of the nominal 2F5 MPER epitope with IgM+ splenic B-cells/mAbs in naïve mice (48). Since it is not clear if IgH allotype impacts affinity and/or specificity of such non-paratopic interactions, in finding no effect of IgH allotype on MPER+ Ab titers/isotypic distribution, our study does not however, exclude its role in non-neutralizing Ab specificity (i.e. by altering signal strength of non-paratopic interactions). In this regard, SPR fine-mapping analysis of serum Abs from immunized IgH congenics on responder (H-2d) MHC backgrounds should be informative.

This study also reveals the atypical nature of TH-B cell collaboration involved in gp41-specific Ab induction. In particular, our functional mapping of the core TH epitope (KWASLWNWF) responsible for the H-2d restriction of MPER+ Ab responses to a region in our minimal MPER immunogens that overlaps several B-cell epitopes (including those bound by BnAbs 2F5 (14), z13 (16) and 4E10 (11,15), as well as residues involved in non-neutralizing/non-paratopic interactions (42,43,48)) contrasts the widely-held notion that TH and B-cell epitopes generally do not overlap (57-59) and would be disadvantageous for B-cell immunogenicity-either due to competition of BCR and Class II molecules for antigen binding (60) or the former interfering with endocytosis/ag processing by the latter (61,62). The generality of this notion, however, has been challenged in later studies (63-68). Regardless, given the poly-/autoreactive nature of MPER+ BnAbs (10,27-29), it is interesting that amongst notable examples of overlapping B-TH epitopes, those involved in auto-Ab responses are prominently represented (reviewed in (69)), with the best characterized of these being against the T1 diabetes autoantigen I-A2 (70). Further highlighting the unusual nature of TH-B cell collaboration in MPER+ Ab responses to immunization, our study also demonstrate elevated MPER+ Ab titers in immunized H-2d congenic strains, irrespective of whether a lipid-anchoring tag, GTH-1, derived from an α-helical region in HIV-1 p24 gag (71), or a gp140 Env protein immunogen are used. Since the former contains an immunodominant TH epitope (38) and the latter contains multiple non haplotype-restricted TH epitopes with considerably higher predicted binding affinities than the I-Ad-restricted, functionally-mapped core TH epitope KWASLWNWF (based on the MHC2PRED algorithm (72)), this strongly suggests that general TH cross-presentation cannot replace MPER+ Ab induction specified by this restricted TH epitope, and therefore contrasts the general notion of significant plasticity/considerable promiscuity existing in CD4 TH epitope cross-presentation by Class II, i.e. relative to that of CTL epitope presentation by Class I (69).

This study's unexpected finding that a haplotype-restricted, B cell-overlapping TH epitope is required for MPER+ Ab induction raises an important question: to what extent are T and B-cell epitopes involved in MPER+ Ab responses functionally-linked? In the general context of Ab responses against vaccination to complex viruses, a degree of TH-B epitope proximity/linkage has been previously demonstrated, which can range from a requirement for TH-B epitopes to be overlapping and/or adjacent, for example, as mutational and overlapping-peptide analysis of influenza-specific CD4 TH clones has shown (66,67), to the other end of the spectrum, for TH-B epitopes to be on the same viral polypeptide, but in different regions, as suggested by comprehensive scanning of functional TH-B epitopes involved in neutralizing Ab responses to Vaccinia immunization (73). Thus, understanding the degree of TH-B- cell epitope linkage involved in MPER+ Ab induction may be important for minimal MPER immunogen design, in two regards. First, assuming that such linkage applies equally to all MPER+ B-cell epitopes (i.e. non-neutralizing and BnAb epitopes), a strategy to successfully re-engineer existing minimal MPER immunogens as TH-B (bi-epitope) immunogens, in order to enhance general TH responses, may specifically need to consider: identifying i) if/which gp41 regions (or portions of Env) contain alternate TH epitopes functionally comparable to the H-2d-restricted TH epitope and ii) determining which ones can be presented by the widest array of haplotypes. Secondly, since successful minimal MPER immunogens will likely also need to be capable of preferentially binding BnAb epitopes, another consideration in their re-design will be to eliminate non-paratopic/non-neutralizing B-cell epitopes and/or improve BnAb epitope sequences. In this regard, the fact that the Class II-restricted TH epitope we have identified overlaps MPER+ BnAb epitopes means that such re-engineering may also destroy critical residues in this overlapping H-2d-restricted TH epitope, and thus, identifying alternate functionally-linked TH epitopes will be critical.

One potentially important, related consideration for optimizing minimal immunogens this study raises is to understand the mechanism by which TH restriction of MPER+ Ab responses occurs. One interesting clue in this regard comes from our comparison of TH epitopes predicted at I-A for the H-2b, H-2k, and H-2s haplotype congenic B10 strains, all identified in this study as non/low MPER+ Ab responders. In particular, while H-2b and H-2k haplotypes present poorly at I-A (the former due to being a generally poor MHC presenter (74), the latter selectively poor for the MPER), the H-2s presents/binds a TH epitope at I-A with an affinity/certainty that is equal to the H-2d responder strain (Table S1). Importantly, however, the predicted TH epitope presented/bound by I-As contains the full 2F5 neutralizing epitope ELDKWA that is also associated with self-reactivity (33,36,75), whereas that presented by I-Ad lacks specificity for the gp41664 aspartic acid residue in the 2F5 neutralization epitope (also lacking and/or decreased in non-neutralizing Ab/non-paratopic footprints in mice (42,48), as well as in the opossum version of the evolutionarily-conserved ELDKWA-containing autoantigen candidate Kynureninase (75)). Given this interesting disparity in the type of TH epitopes presented by non-responder and responder haplotypes, it is tempting to speculate on two, non-mutually exclusive possibilities for how TH restriction of MPER+ Ab responses occurs: i) certain MHC class II haplotypes (like I-Ak) cannot present TH epitopes in the minimal MPER immunogen required for MPER+ Ab induction, but could potentially present ones nearby in gp41 that are functionally linked to BnAb epitopes and, ii) during thymic development, TH epitopes presented at I-A by certain haplotypes (i.e. I-As) interact with, and delete, self-reactive T-cell precursors. Thus, in addition to considering TH epitopes capable of presentation by multiple haplotypes, immunogen design may also need to select TH epitopes based on their lack of self-reactivity. Tracking the fate of developing CD4 TH-cells in immunized H-2d and H-2d congenic strains (using TH epitope-I-Ad/I-As complexed dextramer reagents, respectively) should be helpful in examining both possibilities.

Another important question our study raises is how Class II-restricted TH presentation (and/or deletion of CD4 T-cells) impacts the subdominance of MPER+ BnAb responses. One possibility is that this occurs directly, via the same mechanisms we describe here for non-neutralizing MPER+ Ab responses in “non-responder” haplotypes. Another possibility is that this occurs indirectly, in “responder” haplotypes, via either: 1) further amplification of B-cells expressing non-neutralizing epitopes that preferentially bind Env/MPER immunogens and/or are more frequent in the pre-immune repertoire or are preferentially activated, both by virtue of lacking self-reactivity (and thus not being clonally deleted or anergic, respectively) and 2) further dampening of any potential serum BnAb responses via steric hindrance at the Ab level, by non-neutralizing serum Abs specific for overlapping or nearby epitopes in the HR2 region (41). Our recent observations of Ab responses in the 2F5 KI system have features that support both possibilities. On one hand, that T-independent serum BnAb responses are elicited by vaccination with the TLR-MPER peptide-liposome conjugate immunogen in the 2F5 KI model (36), which was engineered on the C57BL/6 background (and thus bears a “non-responder” (H-2b) haplotype), yet the same immunogen induces T-dependent (T-D) responses in WT strains bearing “responder” haplotypes in this study, argues for a direct effect on 2F5 BnAb T-D responses by class II haplotype restriction. On the other hand, we have recently also shown that spontaneous T-D BnAb responses in the 2F5 KI model are already profoundly limited in the pre-immune (unimmunized) repertoire of residual, peripheral B-cells via loss of 2F5 MPER neutralization epitope binding (36). Because this loss is selective, i.e. occurs predominantly in serum IgG/mature splenic B-cell fractions, and does not impact lipid binding/polyreactivity, this suggests it is driven by reactivity for host (self-) antigens mimicked by 2F5's neutralization epitope (33). Thus, although determining if I-Ab-restriction of T-D MPER+ Ab responses also impacts MPER+ BnAb epitopes (i.e. in addition to non-neutralizing epitopes, and independent of effects that purifying selection against self-reactivity may impart on the pre-immune repertoire) are beyond the scope of this study, comparisons of 2F5 KI (C57BL/6) mice with those backcrossed onto a “responder” haplotype-bearing background, as well as adoptive co-transfer of 2F5 KI and WT responder/non-responder haplotype-bearing B-cells into MHC congenic recipients, will be informative in this regard.

Finally, of general interest will be to determine how the biology of MHC class II haplotype restriction of gp41 MPER+ Ab responses to immunization, elucidated here in mice, relates to those in HIV-1 infected or vaccinated humans. In this regard, a preferential association of class II HLA- DRB1*13 and HLA-DQB1*06 allelic variants with strong, polyfunctional TH responses in HIV-1 infected elite controllers has been reported in a recent study (76), but the status/specificity of any potential BnAb responses were not reported, nor were MPER-specific TH or Ab responses evaluated. With respect to vaccination specifically, Ab responses in RV144 vaccinees (77) have been found to map to the V2 region, in close proximity and/or overlapping to V2-specific TH epitopes in responding CD4 T-cells (78), and furthermore, a preferential association of DRB1*11 and allelic variants with general non-Ab responsiveness, as well that of DQA1*5:01 and DQB1*03:01 HLA-DQ heterodimers with lack of weak (tier 1) neutralizing Ab responses have been found in this same trial (79), thus suggesting haplotype-restriction of responses to this vaccine regimen involving closely-overlapping TH-B cell epitopes. Although currently no analogous functional/genetic associations have yet been made between class II-restricted overlapping TH-B epitopes and non-neutralizing/BnAb MPER+ Ab responses, it is thus tempting to speculate on their involvement, given the heterogeneity in magnitude and timing of α-gp41 non-neutralizing or weakly cross-neutralizing Ab responses (8), as well as the fact that a similar mode of action by which Class II restriction of MPER Ab responses to immunization we see in this study in mice is also potentially involved in α-V2 Ab responses to RV144 vaccination (77-79). Assuming MHC class II restriction by overlapping TH-B epitopes indeed does impact gp41 MPER+ Ab responses in vaccinees, we predict the same mechanisms/considerations identified here would likely apply, since a similar distribution of TH epitopes (in minimal MPER immunogens) are predicted by the IEDB consensus database (80) across human class II alleles as those presented at I-A/I-E by haplotypes in MHC congenic haplotype non-responder/responder groups. Functional mapping of TH and B-cell gp41 MPER epitopes in vaccinees in future MPER immunogen-based vaccine trials, as well as examination of MPER Ab responses in mice bearing human MHC loci (or expressing relevant human Class II allelic variant transgenes identified in such functional screens) may be informative in this regard.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Celia LaBranche for assistance with TZM-b/l neutralization assays, Kara Anasti for help with production and quality control of TLR agonist-MPER peptide-liposomes, and Mattia Bonsignori for technical advice regarding 3H proliferation assays. We are also grateful to the DHVI Flow Cytometry and Immune Reconstitution Facilities for expert assistance, Matt Holl and Garnett Kelsoe for helpful discussions regarding MHC class II prediction algorithms and in vitro re-stimulation assays, respectively, and the Duke Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (5P30-AI064518).

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01AI087202 (to L.V.), a Collaboration for AIDS Vaccine Discovery from the Bill & Melinda Gates foundation (to B.F.H. and L.V.), and the Center For HIV/AIDS Vaccine Immunology National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/National Institutes of Health Grant U19AI067854 (to B.F.H.).

References

- 1.McElrath MJ, Haynes BF. Induction of Immunity to Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type-1 by Vaccination. Immunity. 2010;33:542–554. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mascola JR, Stiegler G, VanCott TC, Katinger H, Carpenter CB, Hanson CE, Beary H, Hayes D, Frankel SS, Birx DL, Lewis MG. Protection of macaques against vaginal transmission of a pathogenic HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus by passive infusion of neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med. 2000;6:207–210. doi: 10.1038/72318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hessell AJ, Rakasz EG, Poignard P, Hangartner L, Landucci G, Forthal DN, Koff WC, Watkins DI, Burton DR. Broadly neutralizing human anti-HIV antibody 2G12 is effective in protection against mucosal SHIV challenge even at low serum neutralizing titers. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000433. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hessell AJ, Rakasz EG, Tehrani DM, Huber M, Weisgrau KL, Landucci G, Forthal DN, Koff WC, Poignard P, Watkins DI, Burton DR. Broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 directed against the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 membrane-proximal external region protect against mucosal challenge by simian-human immunodeficiency virus SHIVBa-L. J Virol. 2010;84:1302–1313. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01272-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balazs AB, Chen J, Hong CM, Rao DS, Yang L, Baltimore D. Antibody-based protection against HIV infection by vectored immunoprophylaxis. Nature. 2012;481:81–84. doi: 10.1038/nature10660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMichael AJ, Borrow P, Tomaras GD, Goonetilleke N, Haynes BF. The immune response during acute HIV-1 infection: clues for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:11–23. doi: 10.1038/nri2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haynes BF, Kelsoe G, Harrison SC, Kepler TB. B-cell-lineage immunogen design in vaccine development with HIV-1 as a case study. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:423–433. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mikell I, Sather DN, Kalams SA, Altfeld M, Alter G, Stamatatos L. Characteristics of the Earliest Cross-Neutralizing Antibody Response to HIV-1. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001251. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stamatatos L, Morris L, Burton DR, Mascola JR. Neutralizing antibodies generated during natural HIV-1 infection: good news for an HIV-1 vaccine? Nat Med. 2009;15:866–870. doi: 10.1038/nm.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verkoczy L, Kelsoe G, Moody MA, Haynes BF. Role of immune mechanisms in induction of HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibodies. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardoso RM, Zwick MB, Stanfield RL, Kunert R, Binley JM, Katinger H, Burton DR, Wilson IA. Broadly neutralizing anti-HIV antibody 4E10 recognizes a helical conformation of a highly conserved fusion-associated motif in gp41. Immunity. 2005;22:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang J, Ofek G, Laub L, Louder MK, Doria-Rose NA, Longo NS, Imamichi H, Bailer RT, Chakrabarti B, Sharma SK, et al. Broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by a gp41-specific human antibody. Nature. 2012;491:406–411. doi: 10.1038/nature11544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muster T, Steindl F, Purtscher M, Trkola A, Klima A, Himmler G, Ruker F, Katinger H. A Conserved Neutralizing Epitope on Gp41 of Human-Immunodeficiency-Virus Type-1. J Virol. 1993;67:6642–6647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6642-6647.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ofek G, Tang M, Sambor A, Katinger H, Mascola JR, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. Structure and mechanistic analysis of the anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2F5 in complex with its gp41 epitope. J Virol. 2004;78:10724–10737. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10724-10737.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stiegler G, Kunert R, Purtscher M, Wolbank S, Voglauer R, Steindl F, Katinger H. A potent cross-clade neutralizing human monoclonal antibody against a novel epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Aids Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:1757–1765. doi: 10.1089/08892220152741450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwick MB, Labriijn AF, Wang M, Spenlehauer C, Sapphire EO, Binley JM, Moore JP, Stiegler G, Katinger H, Burton DR, Parren PW. Broadly neutralizing antibodies targeted to the membrane-proximal external region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp41. J Virol. 2001;75:10892–10905. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10892-10905.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold GF, Velasco PK, Holmes AK, Wrin T, Geisler SC, Phung P, Tian Y, Resnick DA, Ma X, Mariano TM, et al. Broad Neutralization of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) Elicited from Human Rhinoviruses That Display the HIV-1 gp41 ELDKWA Epitope. J Virol. 2009;83:5087–5100. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00184-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frey G, Peng H, Rits-Volloch S, Morelli M, Cheng Y, Chen B. A fusion-intermediate state of HIV-1 gp41 targeted by broadly neutralizing antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3739–3744. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800255105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guenaga J, Dosenovic P, Ofek G, Baker D, WR Schief, Kwong PD, Karlsson Hedestam GB, Wyatt RT. Heterologous Epitope-Scaffold Prime:Boosting Immuno-Focuses B Cell Responses to the HIV-1 gp41 2F5 Neutralization Determinant. Plos One. 2011;6:e16074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montero M, Gulzar N, Klaric KA, Donald JE, Lepik C, Wu S, Tsai S, Julien JP, Hessell AJ, Wang S, Lu S, Burton DR, et al. Neutralizing Epitopes in the Membrane-Proximal External Region of HIV-1 gp41 Are Influenced by the Transmembrane Domain and the Plasma Membrane. J Virol. 2012;86:2930–2941. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06349-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ofek G, Guenaga FJ, Schief WR, Skinner J, Baker D, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. Elicitation of structure-specific antibodies by epitope scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17880–17887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004728107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou M, Kostoula I, Brill B, Panou E, Sakarellos-Daitsiotis M, Dietrich U. Prime boost vaccination approaches with different conjugates of a new HIV-1 gp41 epitope encompassing the membrane proximal external region induce neutralizing antibodies in mice. Vaccine. 2012;30:1911–1916. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denner J. Towards an AIDS vaccine: The transmembrane envelope protein as target for broadly neutralizing antibodies. Hum Vaccines. 2011;7:4–7. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.0.14555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCoy LE, Weiss RA. Neutralizing antibodies to HIV-1 induced by immunization. J Exp Med. 2013;210:209–223. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montero M, van Houten NE, Wang X, Scott JK. The membrane-proximal external region of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope: Dominant site of antibody neutralization and target for vaccine design. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:54–78. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haynes BF, Moody MA, Verkoczy L, Kelsoe G, Alam SM. Antibody polyspecificity and neutralization of HIV-1: a hypothesis. Hum Antibodies. 2005;14:59–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haynes BF, Fleming J, St Clair EW, Katinger H, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Robinson J, Scearce RM, Plonk K, Staats HF, et al. Cardiolipin polyspecific autoreactivity in two broadly neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Science. 2005;308:1906–1908. doi: 10.1126/science.1111781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verkoczy L, Chen Y, Bouton-Verville H, Zhang J, Diaz M, Hutchinson J, Ouyang YB, Alam SM, Holl TM, Hwang KK, Kelsoe G, Haynes BF. Rescue of HIV-1 Broad Neutralizing Antibody-Expressing B Cells in 2F5 VH × VL Knockin Mice Reveals Multiple Tolerance Controls. J Immunol. 2011;187:3785–3797. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verkoczy L, Diaz M, Holl TM, Ouyang YB, Bouton-Verville H, Alam SM, Liao HX, Kelsoe G, Haynes BF. Autoreactivity in an HIV-1 broadly reactive neutralizing antibody variable region heavy chain induces immunologic tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:181–186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912914107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nemazee DA, Burki K. Clonal Deletion of Lymphocyte-B in a Transgenic Mouse Bearing Anti-Mhc Class-I Antibody Genes. Nature. 1989;337:562–566. doi: 10.1038/337562a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erikson J, Radic MZ, Camper SA, Hardy RR, Carmack C, Weigert M. Expression of anti-DNA immunoglobulin transgenes in non-autoimmune mice. Nature. 1991;349:331–334. doi: 10.1038/349331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen C, Nagy Z, Radic MZ, Hardy RR, Huszar D, Camper SA, Weigert M. The Site and Stage of Anti-DNA B-Cell Deletion. Nature. 1995;373:252–255. doi: 10.1038/373252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y, Zhang J, Hwang KK, Bouton-Verville H, Xia SM, Newman A, Ouyang YB, Haynes BF, Verkoczy L. Common tolerance mechanisms, but distinct cross-reactivities associated with gp41 and lipids, limit production of HIV-1 broad neutralizing antibodies 2F5 and 4E10. J Immunol. 2013;191:1260–1275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cambier JC, Gauld SB, Merrell KT, Vilen BJ. B-cell anergy: from transgenic models to naturally occurring anergic B cells? Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:633–643. doi: 10.1038/nri2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodnow CC. B-Cell Tolerance. Curr Opin Immunol. 1992;4:703–710. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90049-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verkoczy L, Chen Y, Zhang J, Bouton-Verville H, Newman A, Lockwood B, Scearce RM, Montefiori DC, Dennison SM, et al. Induction of HIV-1 Broad Neutralizing Antibodies in 2F5 Knockin Mice: selection against MPER-associated autoreactivity limits T-dependent responses. J Immunol. 2013;191:2538–2550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dennison SM, Sutherland LL, Jaeger FH, Anasti KM, Parks R, Stewart S, Bowman C, Xia SM, Zhang R, Shen X, et al. Induction of Antibodies in Rhesus Macaques That Recognize a Fusion-Intermediate Conformation of HIV-1 gp41. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alam SM, McAdams M, Boren D, Rak M, Scearce RM, Gao F, Camacho ZT, Gewirth D, Kelsoe G, Chen P, Haynes BF. The role of antibody polyspecificity and lipid reactivity in binding of broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 envelope human monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 to glycoprotein 41 membrane proximal envelope epitopes. J Immunol. 2007;178:4424–4435. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.7.4424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alam SM, Morelli M, Dennison SM, Liao HX, Zhang R, Xia SM, Rits-Volloch S, Sun L, Harrison SC, Haynes BF, Chen B. Role of HIV membrane in neutralization by two broadly neutralizing antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20234–20239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908713106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klein F, Diskin R, Scheid JF, Gaebler C, Mouquet H, Georgiev IS, Pancer M, Zhou T, Incesu RH, Fu BZ, et al. Somatic mutations of the immunoglobulin framework are generally required for broad and potent neutralization. Cell. 2013;153:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alam SM, Scearce RM, Parks RJ, Plonk K, Plonk SG, Sutherland LL, Gorny MK, Zolla-Pazner S, Vanleeuwen S, Moody MA, Xia SM, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 antibodies that mask membrane proximal region epitopes: Antibody binding kinetics, induction, and potential for regulation in acute infection. J Virol. 2008;82:115–125. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00927-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen X, Dennison SM, Liu P, Gao F, Jaeger F, Montefiori DC, Verkoczy L, Haynes BF, Alam SM, Tomaras GD. Prolonged exposure of the HIV-1 gp41 membrane proximal region with L669S substitution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5972–5977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912381107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicely NI, Dennison SM, Spicer L, Scearce RM, Kelsoe G, Ueda Y, Chen H, Liao HX, Alam SM, Haynes BF. Crystal structure of a non-neutralizing antibody to the HIV-1 gp41 membrane-proximal external region. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1492–1494. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schief WR, Ban YEA, Stamatatos L. Challenges for structure-based HIV vaccine design. Curr Opin HIV Aids. 2009;4:431–440. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832e6184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liao HX, Chen X, Munshaw S, Zhang R, Marshall DJ, Vandergrift N, Whitesides JF, Lu X, Yu JS, Hwang KK, et al. Initial antibodies binding to HIV-1 gp41 in acutely infected subjects are polyreactive and highly mutated. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2237–2249. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tomaras GD, Yates NL, Liu P, Qin L, Fouda GG, Chavez LL, Decamp AC, Parks RJ, Ashley VC, Lucas JT, et al. Initial B-Cell Responses to Transmitted Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1: Virion-BindingI mmunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG Antibodies Followed by Plasma Anti-gp41 Antibodies with Ineffective Control of Initial Viremia. J Virol. 2008;82:12449–12463. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01708-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McMichael AJ, Haynes BF. Lessons learned from HIV-1 vaccine trials: new priorities and directions. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:423–427. doi: 10.1038/ni.2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Verkoczy L, Moody MA, Holl TM, Bouton-Verville H, Scearce RM, Hutchinson J, Alam SM, Kelsoe G, Haynes BF. Functional, Non-Clonal IgM(a)-Restricted B Cell Receptor Interactions with the HIV-1 Envelope gp41 Membrane Proximal External Region. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Banerjee K, Andjelic S, Klasse PJ, Kang Y, Sanders RW, Michael E, Durso RJ, Ketas TJ, Olson WC, Moore JP. Enzymatic removal of mannose moieties can increase the immune response to HIV-1 gp120 in vivo. Virology. 2009;389:108–121. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daly LM, Johnson PA, Donnelly G, Nicolson C, Robertson J, Mills KH. Innate IL-10 promotes the induction of Th2 responses with plasmid DNA expressing HIV gp120. Vaccine. 2005;23:963–974. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gorse GJ, Corey L, Patel GB, Mandava M, Hsieh RH, Matthews TJ, Walker MC, McElrath MJ, Berman PW, Eibl MM, Belshe RB, et al. HIV-1(MN) recombinant glycoprotein 160 vaccine-induced cellular and humoral immunity boosted by HIV-1(MN) recombinant glycoprotein 120 vaccine. Aids Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999;15:115–132. doi: 10.1089/088922299311547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jankovic D, Caspar P, Zweig M, Garcia-Moll M, Showalter SD, Vogel FR, Sher A. Adsorption to aluminum hydroxide promotes the activity of IL-12 as an adjuvant for antibody as well as type 1 cytokine responses to HIV-1 gp120. J Immunol. 1997;159:2409–2417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Seaman MS, Janes H, Hawkins N, Grandpre LE, Devoy C, Giri A, Coffey RT, Harris L, Wood B, Daniels MG, Bhattacharya T, et al. Tiered Categorization of a Diverse Panel of HIV-1 Env Pseudoviruses for Assessment of Neutralizing Antibodies. J Virol. 2010;84:1439–1452. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02108-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dennison SM, Stewart SM, Stempel KC, Liao HX, Haynes BF, Alam SM. Stable docking of neutralizing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 membrane-proximal external region monoclonal antibodies 2F5 and 4E10 is dependent on the membrane immersion depth of their epitope regions. J Virol. 2009;83:10211–10223. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00571-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maggi E, Mazzetti M, Ravina A, Annunziato F, de Carli M, Piccinni MP, Manetti R, Carbonari M, Pesce AM, del Prete G, et al. Ability of HIV to promote a TH1 to TH0 shift and to replicate preferentially in TH2 and TH0 cells. Science. 1994;265:244–248. doi: 10.1126/science.8023142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clerici M, Shearer GM. The Th1/Th2 hypothesis of HIV infection: new insights. Immunol Today. 1994;15:575–581. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benjamin DC, Berzofsky JA, East IJ, Gurd FR, Hannum C, Leach SJ, Margoliash E, Michael JG, Miller A, Prager EM, et al. The antigenic structure of proteins: a reappraisal. Annual Rev Immunol. 1984;2:67–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.02.040184.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bezofsky JA. T-B reciprocity. An Ia-restricted epitope-specific circuit regulating T cell-B cell interaction and antibody specificity. Immunol Res. 1983;79:7739–7743. doi: 10.1007/BF02918417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hachimura S, Enomoto A, Kaminogawa S. Relative positioning of the T cell and B cell determinants on an immunogenic peptide: its influence on antibody response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;169:803–808. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ozaki S, Berzofsky JA. Antibody conjugates mimic specific B cell presentation of antigen: relationship between T and B cell specificity. J Immunol. 1987;138:4133–4142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Unanue ER, Allen PM. The basis for the immunoregulatory role of macrophages and other accessory cells. Science. 1987;236:551–557. doi: 10.1126/science.2437650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kovac Z, Schwartz RH. The molecular basis of the requirement for antigen processing of pigeon cytochrome c prior to T cell activation. J Immunol. 1985;134:3233–3240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kurisaki J, Atassi H, Atassi MZ. T cell recognition of ragweed allergen Ra3: localization of the full T cell recognition profile by synthetic overlapping peptides representing the entire protein chain. Eur J Immunol. 1986;16:236–240. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830160305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nicholas JA, Mitchell MA, Levely ME, Rubino KL, Kinner JH, Harn NK, Smith CW. Mapping an antibody-binding site and a T-cell-stimulating site on the 1A protein of respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol. 1988;62:4465–4473. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4465-4473.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Comerford SA, McCance DJ, Dougan G, Tite JP. Identification of T- and B-cell epitopes of the E7 protein of human papillomavirus type 16. J Virol. 1991;65:4681–4690. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4681-4690.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barnett BC, Graham CM, Burt DS, Skehel JJ, Thomas DB. The immune response of BALB/c mice to influenza hemagglutinin: commonality of the B cell and T cell repertoires and their relevance to antigenic drift. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:515–521. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Graham CM, Barnett BC, Hartlmayr I, Burt DS, Faulkes R, Skehel JJ, Thomas DB. The structural requirements for class II (I-Ad)-restricted T cell recognition of influenza hemagglutinin: B cell epitopes define T cell epitopes. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:523–528. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harris DP, Vordermeier HM, Arya A, Bogdan K, Moreno C, Ivanyi J. Immunogenicity of peptides for B cells is not impaired by overlapping T-cell epitope tolopology. Immunology. 1996;88:348–354. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.d01-673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sette A, Rappuoli R. Reverse vaccinology: developing vaccines in the era of genomics. Immunity. 2010;33:530–541. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dromey JA, Weenink SM, Peters GH, Endl J, Tighe PJ, Todd I, Christie MR. Mapping of epitopes for autoantibodies to the type 1 diabetes autoantigen IA-2 by peptide phage display and molecular modeling: overlap of antibody and T cell determinants. J Immunol. 2004;172:4084–4090. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Haynes BF, Arthur LO, Frost P, Matthews TJ, Langlois AJ, Palker TJ, Hart MK, Scearce RM, Jones DM, McDanal C, et al. Conversion of an Immunogenic Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Envelope Synthetic Peptide to a Tolerogen in Chimpanzees by the Fusogenic Domain of HIV gp41 Envelope Protein. J Exp Med. 1993;177:717–727. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lata S, Bhasin M, Rhagava GP. Application of machine learning techniques in predicting MHC binders. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;409:201–215. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-118-9_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sette A, Moutaftsi M, Moyron-Quiroz J, McCausland MM, Davies DH, Johnston RJ, Peters B, Rafii-El-Idrissi Benhnia M, Hoffmann J, Su HP, et al. Selective CD4+ T cell help for antibody responses to a large viral pathogen: deterministic linkage of specificities. Immunity. 2008;28:847–858. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gustavsson S, Hjulström-Chomez S, Lidström BM, Ahlborg N, Andersson R, Heyman B. Impaired antibody responses in H-2Ab mice. J Immunol. 1998;161:1765–1771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]