Abstract

Background

Upper respiratory infections, acute sinus infections, and sore throats are common symptoms that cause patients to seek medical care. Despite well-established treatment guidelines, studies indicate that antibiotics are prescribed far more frequently than appropriate, raising a multitude of clinical issues.

Methods

The primary goal of this study was to increase guideline adherence rates for acute sinusitis, pharyngitis, and upper respiratory tract infections (URIs). This study was the first Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle in a quality improvement program at an internal medicine resident faculty practice at a university-affiliated community hospital internal medicine residency program. To improve guideline adherence for respiratory infections, a package of small-scale interventions was implemented aimed at improving patient and provider education regarding viral and bacterial infections and the necessity for antibiotics. The data from this study was compared with a previously published study in this practice, which evaluated the adherence rates for the treatment guidelines before the changes, to determine effectiveness of the modifications. After the first PDSA cycle, providers were surveyed to determine barriers to adherence to antibiotic prescribing guidelines.

Results

After the interventions, antibiotic guideline adherence for URI improved from a rate of 79.28 to 88.58% with a p-value of 0.004. The increase of adherence rates for sinusitis and pharyngitis were 41.7–57.58% (p=0.086) and 24.0–25.0% (p=0.918), respectively. The overall change in guideline adherence for the three conditions increased from 57.2 to 78.6% with the implementations (p<0.001). In planning for future PDSA cycles, a fishbone diagram was constructed in order to identify all perceived facets of the problem of non-adherence to the treatment guidelines for URIs, sinusitis, and pharyngitis. From the fishbone diagram and the provider survey, several potential directions for future work are discussed.

Conclusions

Passive interventions can result in small changes in antibiotic guideline adherence, but further PDSA cycles using more active methodologies are needed.

Keywords: antibiotic, guideline, adherence

The diagnoses of upper respiratory tract infections (URI), acute sinus infections, and pharyngitis are common conditions that cause patients to seek medical care. Every year approximately 25 million people visit their primary care physician with uncomplicated URIs and approximately 1–2% of all hospital visits involve individuals presenting with a complaint of sore throat (1–4). Despite well-established treatment guidelines (Table 1), studies indicate that URIs and bronchitis account for 75% of unnecessary antibiotics prescribed in the hospital setting (5). In addition, a national survey revealed that 73% of adults with pharyngitis in the United States received antibiotics, a much higher percentage than would be indicated by application of the present guidelines (6–9).

Table 1.

Antibiotic prescribing guidelines

| Diagnosis | Guidelines |

|---|---|

| Pharyngitis | Bisno, et al. Clinic Infect Dis 2002 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | Wong et al. Am Fam Physician 2006 |

| Sinusitis | Rosenfeld, et al. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007 |

Given the high volume of respiratory cases seen in the ambulatory and emergency department settings, over-prescription of antibiotics for these illnesses raises the specter of bacterial drug-resistance (10). This rise of resistance can lead to an increase in the morbidity and mortality risks for patients in the community, as well as potentially increasing the costs of treating infectious diseases (11). In response, various organizations are analyzing methods to decrease the unnecessary use of antibiotics. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has launched a national campaign to promote appropriate antimicrobial drug use aimed at educating clinicians and the public, and developing and implementing interventions to promote changes in prescribing practice (12).

In a previously published study evaluating the effect of the presence of a learner on guideline adherence, overall guideline adherence was found to be poor, particularly for pharyngitis. The primary goal of this study was therefore to increase treatment guideline adherence rates for acute sinusitis, pharyngitis, and URI through a quality improvement initiative (13).

Methods and analysis

This program was the first Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle in a quality improvement program at an internal medicine resident faculty practice at a university-affiliated community hospital internal medicine residency program. On October 1, 2012, the practice introduced three simultaneous interventions to increase treatment guideline adherence for these respiratory infections. First, the guidelines were sent via email to all providers of the medical practice, including the six attending physicians, 23 residents, and one nurse practitioner (14–16). In the second intervention, CDC educational posters depicting the appropriate treatment of viral URIs were placed in examination rooms (http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/campaign-materials/posters.html). These were provided in English and Spanish, the two principal languages spoken by the practice patient population. For the third intervention, providers were educated about the CDC Get Smart: Know When Antibiotics Work prescription pads (www.cdc.gov/getsmart/campaign-materials/print-materials/ViralRxPad.html). These were made available in examination rooms and in the preceptor conference room.

From October 1, 2012, to February 4, 2013, visits were identified using Centricity (GE Healthcare, London, England) electronic medical records by searching ICD-9 codes for diagnosis of URI (ICD-9 code 465.9), sinusitis (ICD-9 codes 461.8, 461.9, 473.9), and sore throat/pharyngitis (ICD-9 codes 034.0, 462.0). On February 4, the practice switched to the Epic electronic health record system (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, Wisconsin). Under this system, patients were identified by searching acute patient encounters for visit diagnoses of URI, sinusitis, or pharyngitis.

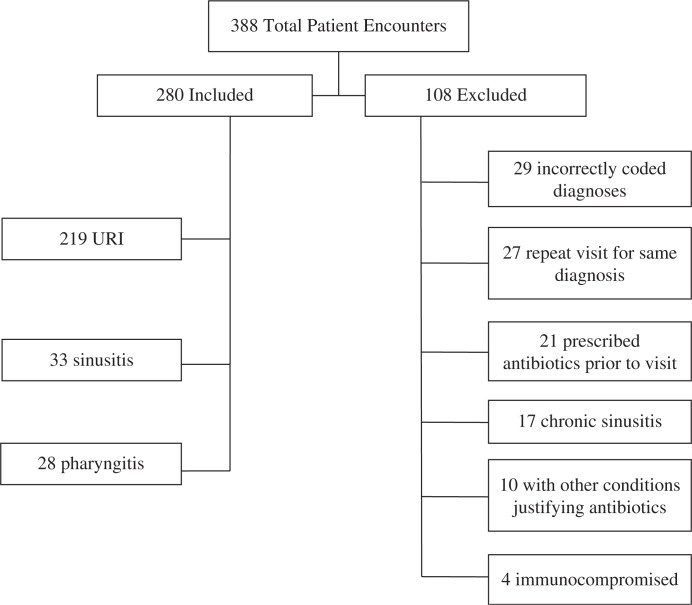

A total of 388 visits were identified from October 1, 2012, through June 28, 2013. In 280 visits, the encounter met the inclusion criteria. The remaining 108 visits met one of the following exclusion criteria: chronic sinusitis, incorrectly coded diagnoses, immunocompromised state, other concurrent medical conditions justifying antibiotic prescription, repeat visits for the same diagnosis, and receipt of antibiotics prior to the visit (Fig. 1). A trained research associate performed a chart review to determine guideline adherence. The research associate and one physician author reviewed the first 10% of all cases simultaneously, and thereafter every 10th case was independently reviewed by the physician author to reduce inter-rater variability. Agreement between reviewers was 100%.

Fig. 1.

Patient population.

The data were pooled by year and compliance and analysis was performed by Chi-square test of association using SPSS software (International Business Machines, Armonk, New York). Significance was determined by p-values less than 0.05.

At a required conference at the conclusion of the interventions, an anonymous survey was distributed to all of the providers which explored familiarity with and barriers to guideline adherence. The survey was collected by a non-participant clerical staff member. Response rate was 88% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Survey results for practicing members

| How many years has it been since you graduated from medical school? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Years | Total | Percentage | |

| 0–5 | 23 | 76.67 | |

| 6–10 | 3 | 10 | |

| 11–15 | 1 | 3.33 | |

| More than 15 years | 3 | 10 | |

| For the diagnoses of pharyngitis, URI, and sinusitis, how well do you know believe that you know the treatment guidelines? | |||

| Total | Percentage | ||

| Not at all | 0 | 0 | |

| Mildly well | 10 | 33.33 | |

| Moderately well | 16 | 53.33 | |

| Very well | 4 | 13.33 | |

| For the diagnoses of pharyngitis, URI, and sinusitis, how often do you believe you prescribe antibiotics in a guideline adherent manner? | |||

| Total | Percentage | ||

| 0–25% of the time | 6 | 20.0 | |

| 26–50% of the time | 8 | 26.67 | |

| 51–75% of the time | 10 | 33.33 | |

| 76–100% of the time | 6 | 20.0 | |

| For each of the following factors that might influence your decision to prescribe antibiotics, please indicate the importance of each factor: | |||

| Total | Percentage | ||

| Patient desires antibiotics | Not at all important | 12 | 40.00 |

| Mildly important | 14 | 46.67 | |

| Moderately important | 3 | 10.0 | |

| Very important | 1 | 3.33 | |

| Uncertainty in diagnosis | Not at all important | 2 | 6.67 |

| Mildly important | 13 | 43.33 | |

| Moderately important | 14 | 46.67 | |

| Very important | 1 | 3.33 | |

| Lack of knowledge guidelines | Not at all important | 5 | 16.67 |

| Mildly important | 11 | 36.67 | |

| Moderately important | 10 | 33.33 | |

| Very important | 4 | 13.33 | |

| Lack of clinical decision support tools | Not at all important | 6 | 20.0 |

| Mildly important | 16 | 53.33 | |

| Moderately important | 7 | 23.33 | |

| Very important | 1 | 3.33 | |

Results

The change of adherence rates can be found in Table 3. After the interventions, guideline adherence for URI improved from 79.28 to 88.58% (p=0.004). The increase of adherence rates for sinusitis and pharyngitis were 41.7–57.58% (p=0.086) and 24.0–25.0% (p=0.918), respectively, but both were not statistically significant. The overall guideline adherence rate for the three conditions increased from 57.2 to 78.6% (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Guideline adherence rates

| Guideline | 2008–2012 (12) | 2013 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sinusitis | No | 130 | 14 | 0.086 |

| Yes | 93 | 19 | ||

| Total | 223 | 33 | ||

| Compliance % | 41.70 | 57.58 | ||

| Pharyngitis | No | 104 | 21 | 0.918 |

| Yes | 33 | 7 | ||

| Total | 147 | 28 | ||

| Compliance % | 24.09 | 25.00 | ||

| URI | No | 75 | 25 | 0.004 |

| Yes | 287 | 194 | ||

| Total | 362 | 219 | ||

| Compliance % | 79.28 | 88.58 | ||

| Total cases | No | 309 | 60 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 413 | 220 | ||

| Total | 722 | 280 | ||

| Compliance % | 57.2 | 78.6 |

The results of the survey can be found in Table 2. Most providers completed medical school in the preceding five years. The majority (86%) of respondents believed that they did not know the treatment guidelines ‘very well’, and 83% believed a ‘lack of knowledge of the guidelines’ contributed to their decision to prescribe antibiotics. Only 20% of respondents believed they prescribed antibiotics according to the guidelines more than 75% of the time and 80% indicated that the lack of clinical decision support tools might have been a factor influencing a decision to prescribe antibiotics.

Discussion

The addition of these simultaneous passive, small-scale interventions resulted in a significant increase in guideline adherence rate for the treatment of URIs and trended toward significance for sinusitis. However, pharyngitis guideline adherence did not improve. Previous studies within the practice have indicated that patient age and comorbidities, day of the week, month of the year, and fear of a callback or second visit for the same issue were not determinants of guideline adherence (13). From the provider survey, lack of knowledge of the guidelines and guideline complexity were identified to be major contributors to non-adherence.

Appropriate antibiotic treatment for Streptococcal pharyngitis is determined by the Modified Centor score, which incorporates criteria of fever, tonsillar exudates or swelling, absence of cough, presence of lymphadenopathy, and age (17). Applying the score to the clinical decision making of experienced clinicians improves the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis to 64–83% and 67–91%, respectively (17). Additionally, its use has been estimated to reduce inappropriate antibiotic treatment by as much as 88% (18). A score greater than 4 requires antibiotics, while a score of 2–3 calls for throat culture or rapid Streptococcal antigen test. Rigorous application can be challenging in real time clinical situations. In one center where rapid antigen testing was routinely performed and backup culture or DNA probe was immediately available, the rates of antibiotic prescribing, even with multiple negative tests, was still unacceptably high, with 56% of patients presenting with pharyngitis receiving antibiotics and only 18% of patients having confirmed Streptococcal pharyngitis (19).

In contrast to previous studies, this practice's non-adherence to pharyngitis treatment guidelines resulted not only from the expected unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, but also unwarranted throat cultures. Embedded within the guidelines produced by the American College of Physicians and the CDC on the principles of appropriate antibiotic usage for acute pharyngitis is the necessary requirement to clinically screen all patients with the Centor criteria and only order a throat culture when warranted by this screening process (14). Therefore, ordering a throat culture when not indicated by this score is a violation of the treatment guidelines. In 57% of the non-adherent visits, unnecessary cultures were the only violation of the guidelines. In this facility, the cost of a Streptococcal culture is $51.75. If the test is positive, there is a further charge of $22.25 for organism identification. All of the cultures performed in a non-guideline adherent manner were negative, resulting in a $621.00 increase in cost in this small study. If this non-adherence mirrors other practices, this would result in a significant unnecessary cost to the health care system.

The survey results also suggest that adherence to complex diagnostic algorithms might be improved by the application of a different didactic process for future PDSA cycles. The bulk of respondents were residents who are learning about these illnesses. The majority believed they did not know the treatment guidelines very well although they had been distributed widely. The majority recognized this contributed to their decision to prescribe antibiotics inappropriately, and acknowledged that the lack of clinical decision support tools might have been a factor influencing a decision to prescribe antibiotics. This is particularly important because electronic clinical decision support tools theoretically inform and educate patients and providers on the correct plan of care, and limit external pressure to prescribe antibiotics. In the provider survey, 50% responded that a patient's desire for antibiotics would have some influence on their decision to prescribe them, indicating strong social pressure to prescribe antibiotics.

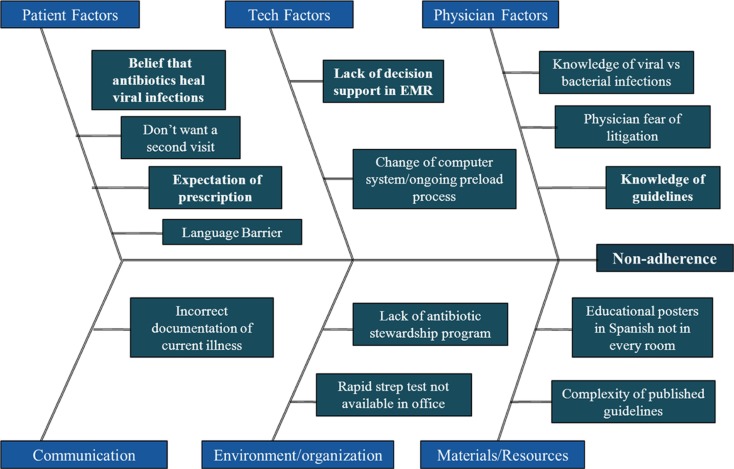

In planning for a second PDSA cycle, a fishbone diagram was constructed to identify all facets of the problem (Fig. 2). As was learned from the survey, context specificity of an intervention is important to the future success. For example, in a region where patient expectation is the driver for antibiotic prescribing, an intervention of a clinical decision support tool aimed at calculating scores to educate providers about guidelines would be less effective than a community outreach to change the antibiotic-requesting culture of the community (20). From the fishbone diagram and the provider survey, it appears that technological solutions may be helpful in improving our adherence rates. The Modified Centor score is complicated and requires calculation, and a clinical decision support tool designed to assist providers unfamiliar with the guideline may help to increase adherence rates. However, the incorporation of clinical decision support tools into electronic health records has had disappointing results overall, and, in this particular venue, has been shown to reduce broad spectrum antibiotic usage to more narrow spectrum antibiotics, but did not reduce the rate at which antibiotics were inappropriately prescribed in the first place (21). The educational intervention for the providers in the practice was a passive distribution of the guidelines. Future PDSA cycles will include more active methodology, such as: incorporation of relevant cases into the ambulatory morning report series; inclusion of this project into the formal residency program quality improvement series; provider report cards; and consideration of a peer academic detailing program, which was recently shown effective in improving antibiotic prescribing in acute respiratory tract infections (22).

Fig. 2.

Fishbone diagram for non-adherence with guidelines.

This study had several limitations. First, the providers were not educated in advance regarding appropriate diagnosis codes, resulting in different coding of the same illness, for example, coding cough rather than URI. Due to wall space limitations, either an English or a Spanish poster was placed in the patient rooms, rather than both, which could have limited its educational potential. As this was a quality improvement initiative pertaining to office visits only, there are no data on prescribing patterns with telephone calls. Finally, this study was performed in a single primary care practice; therefore, the generalizability of the findings may be limited.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Heikkinen T, Järvinen A. The common cold. The Lancet. 2003;361(9351):51–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12162-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, Gonzalez R, Hickner JM, et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults: Background. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37(6):711–19. doi: 10.1067/s0196-0644(01)70090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humair JP, Revaz SA, Bovier P, Stalder H. Management of acute pharyngitis in adults: Reliability of rapid streptococcal tests and clinical findings. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(6):640–4. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.6.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Underland DK, Kowalski TJ, Berth WL, Gundrum JD. Appropriately prescribing antibiotics for patients with pharyngitis: A physician-based approach vs a nurse-only triage and treatment algorithm. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(11):1011–15. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzales R, Malone DC, Maselli JH, Sande MA. Excessive antibiotic use for acute respiratory infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(6):757–62. doi: 10.1086/322627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, Jr, Kaplan EL, Schwartz RH. Practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:113–25. doi: 10.1086/340949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong DM, Blumberg DA, Lowe LG. Guidelines for the use of antibiotics in acute upper respiratory tract infections. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(6):956–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, Cheung D, Eisenberg S, Ganiats TG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines: Adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(Suppl 1):s1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bisno AL. Acute pharyngitis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:205–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy S. Antibiotic resistance: Consequences of inaction. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(Suppl 3):124–9. doi: 10.1086/321837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawkey PM, Jones AM. The changing epidemiology of resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64(Suppl 1):i3–10. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell D. Promoting appropriate antimicrobial drug use: Perspective from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(Suppl 3):245–50. doi: 10.1086/321857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crocker A, Alweis R, Scheirer J, Schamel S, Wasser T, Levengood K. Factors affecting adherence to evidence-based guidelines in the treatment of URI, sinusitis, and pharyngitis. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2013;3:20744. doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v3i2.20744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, Gozales R, Hickner JM, et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults: Background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(6):509–17. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-6-200103200-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzales R, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, Hickner JM, Hoffman JR, Sande MA. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for treatment of nonspecific upper respiratory tract infection: Background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(6):490–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-6-200103200-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hickner JM, Bartlett JG, Besser RE, Gonzales R, Hoffman JR, Sande MA. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute rhinosinusitis in adults: Background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(6):498–505. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-6-200103200-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McIsaac WJ, Kellner JD, Aufricht P, Vanjaka A, Low DE. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1587–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McIsaac WJ, Goel V, To T, Low DE. The validity of a sore throat score in family practice. CMAJ. 2000;163:811–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakhoul GN, Hickner J. Management of adults with acute streptococcal pharyngitis: Minimal value for backup strep testing and overuse of antibiotics. JGIM. 2013;28(6):830–4. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2245-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzales R, Metlay JP. Shifting the paradigm for promoting appropriate antibiotic use. JGIM. 2013;28(6):756–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2444-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Litvin CB, Ornstein S, Wessell AM, Nemeth LS, Nietert PJ. Use of an electronic health record clinical decision support tool to improve antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections: The ABX-TRIP Study. JGIM. 2013;28(6):810–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2267-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gjelstad S, Hoye S, Straand J, Brekke M, Dalen I, Lindbaek M. Improving antibiotic prescribing in acute respiratory tract infections: Cluster randomized trial from Norwegian general practice (prescription peer academic detailing (Rx-PAD) study) BMJ. 2013;347:f4403. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]