Abstract

The clinical use of bioprosthetic heart valves (BHV) is limited due to device failure caused by structural degeneration of BHV leaflets. In this study we investigated the hypothesis that oxidative stress contributes to this process. Fifteen clinical BHV that had been removed for device failure were analyzed for oxidized amino acids using mass spectrometry. Significantly increased levels of ortho-tyrosine, meta-tyrosine and dityrosine were present in clinical BHV explants as compared to the non-implanted BHV material glutaraldehyde treated bovine pericardium (BP). BP was exposed in vitro to oxidizing conditions (FeSO4/H2O2) to assess the effects of oxidation on structural degeneration. Exposure to oxidizing conditions resulted in significant collagen deterioration, loss of glutaraldehyde cross-links, and increased susceptibility to collagenase degradation. BP modified through covalent attachment of the oxidant scavenger 3-(4-hydroxy-3,5-di-tert-butylphenyl) propyl amine (DBP) was resistant to all of the monitored parameters of structural damage induced by oxidation. These results indicate that oxidative stress, particularly via hydroxyl radical and tyrosyl radical mediated pathways, may be involved in the structural degeneration of BHV, and that this mechanism may be attenuated through local delivery of antioxidants such as DBP.

Keywords: Bioprosthesis, heart valve, oxidation, antioxidant, collagen, calcification

1. Introduction

Heart valve replacement surgery is the primary treatment option for progressive, symptomatic heart valve diseases, including aortic valve stenosis and mitral valve prolapse. Each year more than 300,000 valve replacement surgeries are performed in the U.S. with both mechanical valves and bioprosthetic heart valves (BHV) [1]. BHV, which are fabricated from glutaraldehyde treated bovine pericardium (BP), bovine jugular vein, or porcine aortic valve leaflets, have significant advantages over the mechanical valves including a lower risk of thrombosis [2]. In addition, BHV are currently the only type of prosthetic valves that can be catheter deployed as an interventional device [3]. Unfortunately, the use of BHV is limited by poor durability leading to a relatively short device lifespan. BHV begin to fail clinically an average of 10 years following the original valve replacement due to leaflet malfunction caused by structural degeneration associated with either calcification or primary leaflet degeneration [4].

Clinical pathology studies have identified calcification as a major contributor to BHV failure. Therefore the primary focus of the BHV field has been both investigations of calcification mechanisms and the development of anti-calcification strategies involving either alternative fixatives to glutaraldehyde, material pre-treatment, or local drug delivery [5]. Despite the advances in anti-calcification treatments, BHV structural degeneration remains a significant problem. There are no clinical results at this time demonstrating clear efficacy of any of the anti-calcification strategies. Clinical-pathology studies of BHV have suggested alternative mechanisms of BHV degeneration including mechanical stress [6], inflammation [7–9], immune responses [10], and collagen damage not associated with calcification [11, 12]. Therefore, the development of strategies targeting alternative mechanisms of BHV structural degeneration may be effective in mitigating clinical BHV failure.

Oxidative stress has been identified as an important cause of material failure for synthetic biomaterials such as polyurethane pacemaker leads and metal alloy joint prostheses [13], but has not been studied as a mechanism of BHV structural degeneration. Implantable biomaterials such as BHV and synthetic materials in general elicit a foreign body reaction associated with acute and chronic inflammation [14]. Inflammatory cells that are recruited to the site of biomaterial implants produce reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) that can cause post translational oxidative modifications to proteins. For synthetic materials, oxidative stress can lead to material cracking, pitting, and impaired function [13, 15]. The effects of ROS/RNS on BHV have not been investigated, but the mechanisms likely involved have been studied in systems using purified collagen, a major component of BHV. Reactions of oxidants with collagen result in the formation of structurally specific oxidative modifications including o,o'-dityrosine, a tyrosyl radical mediated cross-link, the non-physiological isomers otyrosine and m-tyrosine formed by hydroxyl radical modification phenylalanine, as well as an increase in susceptibility to degradation by proteolytic enzymes [16–19]. Based on these previous studies, we hypothesize that oxidative or nitrative stress by specific pathways may cause structural modification to BHV.

Here we investigate the effects of oxidative stress on BHV using clinical-pathologic BHV explants as well as experimental models with BP and BP covalently modified with the oxidant scavenger DBP. Clinical BHV explanted for device failure were analyzed for the presence of oxidized amino acids with stable isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Experimental systems involving BP exposure to oxidizing conditions were used to assess the effects of oxidation on BHV and the capacity of DBP to provide resistance to oxidative damage.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Biosol and Bioscint were purchased from National Diagnostics (Atlanta, GA). Amplex Red was purchased from Life Technologies (Philadelphia, PA). Glutaraldehyde was purchased from Polysciences, Inc (Warrington, PA). 3H-glutaraldehyde and [2,3-14C]-methyl acrylate were purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO). All chemicals unless otherwise specified were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

2.2 Synthesis of DBP

DBP was synthesized through the reaction of 2,6-di-tert-butylphenol with methyl acrylate under catalysis with a mixture of NaOH and KOH. The resulting methyl 3-(4-hydroxy-3,5,-di-tert-butylphenyl)propionate was reduced with lithium aluminum hydride in ethyl ether to 3-(4-hydroxy-3,5,-di-tert-butylphenyl)propanol, which was transformed into the mesylate by treatment with methanesulfonyl chloride and triethylamine in dichloromethane. The mesylate was reacted with phthalimide potassium salt in 1-methylpyrrolidinone and the phthalimide derivative was cleaved with hydrazine in ethanol to DBP-amine base, which was finally transformed into its water-soluble hydrochloride.

14C-DBP hydrochloride (7 μCi/mmol) was prepared similarly, using [2,3-14C]-methyl acrylate (10 – 20 mCi/mmol) diluted with the non-labeled compound. The only difference between this radiolabeling synthesis and the non-radioactive procedure was at the first step, where an excess of 2,6-di-tert-butylphenol was applied to react the labeled acrylate as completely as possible.

2.3 Clinical BHV explants

Between 2010 and 2012, 15 explanted bovine pericardial BHV were collected from patients according to the University of Pennsylvania IRB approved protocol #809349. Informed consent was obtained from patients requiring repeat aortic valve replacement due to a failing BHV at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Patients with bioprosthetic aortic valve failure due to pannus, thrombus, and endocarditis were excluded from the study. Explanted bioprosthetic aortic valves were fixed in 10% buffered formalin overnight, followed by dehydration in 70% ethanol solution, and stored at 4°C. BHV leaflets were embedded in paraffin according to standard procedures.

2.4 Quantification of oxidized amino acids in clinical explants

Oxidized amino acids were quantified by established stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC MS/MS) methods [20] on an AB SCIEX API 5000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer interfaced with an Aria LX Series HPLC multiplexing system (Cohesive Technologies Inc., Franklin, MA). Briefly, paraffin embedded BHV leaflets were deparaffinized by xylene. [13C6]-labeled oxidized amino acid standards and universal labeled precursor amino acids ([13C9,15N1]tyrosine and [13C9,15N1]phenylalanine) were added to samples after protein delipidation and desalting with a single phase mixture of H2O/methanol/H2O-saturated diethyl ether (1:3:8 v/v/v). Proteins were hydrolyzed under argon gas in methane sulfonic acid, and then samples were passed through C18 solid-phase extraction column (Discovery – DSC18 minicolumn, 3 ml, Supelco, Bellefone, PA) prior to MS analysis. Individual oxidized amino acids and their precursors were monitored by characteristic parent to product ion transitions unique for each isotopologue monitored. Results are expressed relative to the content of the precursor amino acids, tyrosine and phenylalanine.

2.5 BP treatments and DBP modification

Fresh BP obtained from an abattoir was treated with 0.625% glutaraldehyde or 0.625% 3H-glutaraldehyde (specific activity 24 μCi/mmol) in HEPES buffer pH 7.4 for 7 days at room temperature with gentle shaking. BP was modified with DBP through a carbodiimide-driven reaction. The DBP modification reaction was prepared as two solutions: 42 mM DBP in 100% ethanol and 43 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide (SuOH) in deionized H2O. Immediately before adding the BP, the two solutions were combined and 65 mM 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) was added. The reaction proceeded for 24 hours at room temperature with gentle shaking. DBP modified BP was rinsed for 10 minutes in 100% ethanol to remove precipitate formed during the reaction. As a control for the effects of DBP, BP was treated with the carbodiimide reaction with the exclusion of DBP (Glut-EDC/SuOH). All BP samples were stored in 0.2% glutaraldehyde.

Glutaraldehyde fixed BP was reacted with [bis(trifluooacetoxy)iodo]benzene (BTI) to convert asparagine (Asn) and glutamine (Gln) residues to diaminopropionic acid and diaminobutanoic acid, respectively, and prevent the conversion of Asn to aspartic acid (Asp) and Gln to glutamic acid (Glu) during acid hydrolysis. BTI derivatization was performed in 5 M guanidine-HCl and 10 mM trifluoroacetic acid for 4 hours at 60° C. BP was then hydrolyzed in 6 N HCl, dried under air at 60° C, and reconstituted for amino acid analysis by HPLC at the CHOP Metabolomics Core Facility.

BP was modified with 14C-DBP through the carbodiimide-driven reaction to quantify the attachment of DBP to BP. Lyophilized 14C-DBP modified BP was solubilized with Biosol at 50 °C with shaking for 72 hours. Solubilized tissues were added to Bioscint and analyzed by liquid scintillation counting.

2.6 Oxidation capacity of DBP BP

The oxidation reporter molecule Amplex Red was used to determine the oxidant scavenging capacity of DBP modified BP in a system containing myeloperoxidase (MPO) (1 μg/mL), H2O2( 10 μM), and either Cl− (120 mM NaCl) or NO2− (100 μM NaNO2) ions. Amplex red (50 μM) was added to the BP samples immediately after adding H2O2, MPO and NaCl or NaNO2. Fluorescence of the solution at an excitation/emission of 560/590 nm was determined 30 minutes after adding Amplex Red in order to quantify the formation of resorufin, the product of Amplex Red oxidation.

2.7 Accelerated oxidative damage model

BP samples were placed in PBS or 1% H2O2/100 μM FeSO4 for 7 days with solution changes every 2–3 days. Lyophilized samples were weighed at the start and end of treatments. Picrosirius red staining was done on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded samples using 0.1% Sirius red in saturated picric acid. BP treated with 3H-glutaraldehyde was monitored for the release of 3H throughout the assay, as well as in the solubilized tissues at the end of the treatments. Collagenase digestion was performed on lyophilized BP following the 7 day oxidation assay. Collagenase (600 U/mL) was added to BP samples and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. Digestion by collagenase was measured as a loss of weight following collagenase treatment.

2.8 Statistical Methods

Results are shown as the mean ± standard error for the mean. Single ANOVA with Tukey's test, Mann-Whitney rank sum test or a two tailed t-test were used to determine significance, which was defined as a p value less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Analyses of clinical BHV explants

The patient population had roughly equal numbers of males and females (Table 1), and concomitant heart surgery was performed in 6 of the 15 subjects (Table 1). All of the explanted BHV were Carpentier Edwards bioprostheses except for one Sorin bioprosthetic heart valve. Variable amounts of calcification were present in all explants per surgical pathology examination (data not shown), and quantitation of the calcium levels in the leaflets was determined to not be feasible. The majority of the patients had underlying medical conditions (Table 1), and no attempt was made to correlate this diagnostic information with the oxidized amino acid data.

Table 1. Patient characteristics from clinical BHV explants.

NYHA, New York Heart Association; CABG, Coronary artery bypass grafting.

| Clinical Data | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Variable | Value |

| Age | 62.9 ± 17.0 (31–82) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 53% (8) |

| Female | 47% (7) |

| Previously Bicuspid Aortic Valve | 53% (8) |

| Arterial Hypertension | 67% (10) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 60% (9) |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 40% (6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 47% (7) |

| Renal Disease | 20% (3) |

| Smoking History | 20% (3) |

| NYHA | |

| Class I | 0% (0) |

| Class II | 27% (4) |

| Class III | 40% (6) |

| Class IV | 27% (4) |

| Prosthetic Valve Information | |

| Carpentier-Edwards | 93% (14) |

| Sorin | 7% (1) |

| Explanted Valve Size (mm) | |

| 19 | 13% (2) |

| 21 | 27% (4) |

| 23 | 20% (3) |

| 25 | 13% (2) |

| 27 | 27% (4) |

| Valve Age | 7.2 ± 1.8 (4.0–10.9) |

| Concomitant Surgery | |

| None | 60% (9) |

| CABG | 13% (2) |

| Mitral Valve Repair | 13% (2) |

| Mitral Valve Replacement | 7% (1) |

| Ascending Aorta Replacement | 13% (2) |

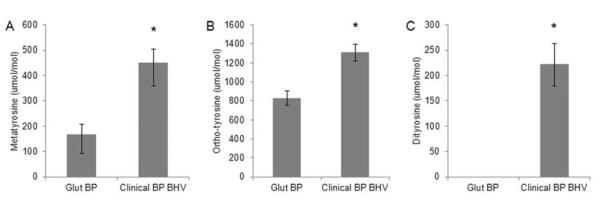

Clinical BP BHV explants were analyzed for structurally distinct oxidative modifications with mass spectrometry, including meta-tyrosine, ortho-tyrosine, and dityrosine. Compared to non-implanted BP, clinical BHV had elevated levels of meta-tyrosine (168.0 ± 40.8 control vs. 448.8 ± 56.5 clinical BHV μmol/mol, p = 0.011), ortho-tyrosine (828.3 ± 76.1 control vs. 1307.8 ± 89.3 clinical BHV μmol/mol, p = 0.009), and dityrosine (0 ± 0 control vs. 221.4 ± 41.5 clinical BHV μmol/mol, p = 0.002) (Fig. 1). Significance was determined with a Mann-Whitney rank sum test. These results demonstrate that clinical BHV are exposed to oxidative stress, and are thereby subject to oxidative modification.

Fig. 1. Oxidized amino acid levels are elevated in clinical BHV.

(A)–(C) Quantification of oxidized amino acid levels in non-implanted control tissue (Glut BP, n = 5) and clinical BP BHV samples (n = 15). *p < 0.05 vs Glut BP.

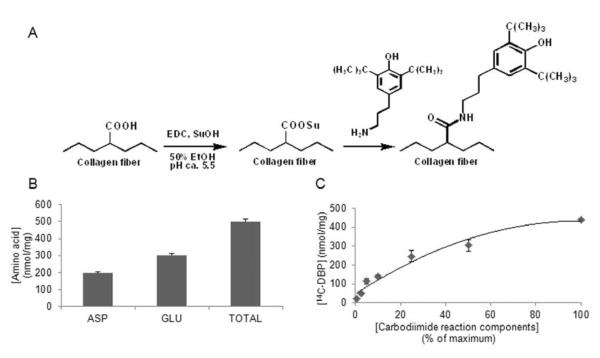

3.2 DBP modification of BP

A carbodiimide-driven reaction was used to attach DBP to BP (Fig. 2A). To estimate the maximum binding capacity of DBP to BP, we quantified the molar concentration of Asp and Glu residues in acid-hydrolyzed BP samples with HPLC. We found that there are 196 ± 7 nmol Asp/mg dry BP and 303 ± 10 nmol Gln/mg for a total of 499 ± 17 nmol of terminal carboxyl-containing amino acid residues per mg of BP (Fig. 2B). Therefore the maximum attachment of DBP is 500 nmol/mg based on amino acid composition.

Fig. 2. Covalent modification of BHV material bovine pericardium with the oxidant scavenger DBP.

(A) Schematic of the carbodiimide-driven reaction used to modify collagen-based tissues with DBP. The carboxyl groups of the collagen fibers are activated with EDC. SuOH stabilizes the O-acylisourea intermediates to enable the amine of DBP to react and form an amide bond. (B) Quantification of Asp and Glu in pericardium by HPLC. Asp and Glu provide carboxyl groups that react with DBP. (C) Dose curve of DBP attachment to pericardium, generated with 14C-DBP.

The attachment of DBP to BP was quantified using 14C-labeled DBP. A dose curve of DBP modified BP was generated through dilutions of the DBP reaction solution in 50% ethanol (Fig. 2C). The amount of DBP attached to BP using the undiluted reaction solution was 439 ± 8 nmol/mg. This result demonstrates that the reaction of DBP with BP results in nearly maximum attachment of DBP to BP based on the predicted binding determined by Asp and Glu quantification.

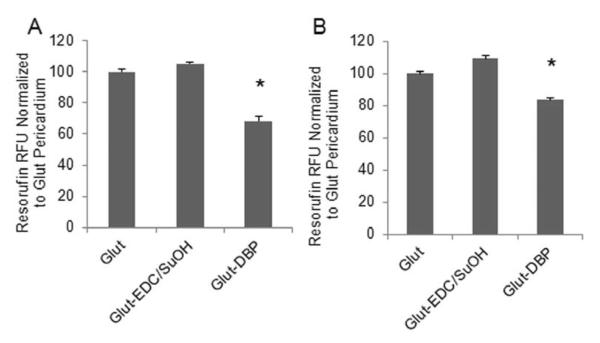

3.3 Oxidant scavenging capacity of DBP modified BP

The oxidation reporter molecule Amplex Red was used to determine the oxidant scavenging capacity of DBP modified BP. Oxidation of Amplex Red to resorufin was accomplished by oxidants generated by MPO in the presence of hydrogen peroxide and either chloride or nitrite. Significantly less Amplex red was oxidized to resorufin in the presence of DBP modified BP as compared to unmodified BP (Fig. 3) demonstrating the capacity of DBP to scavenge oxidants.

Fig. 3. DBP scavenges oxidants after attachment to BP.

Oxidation of Amplex Red to resorufin with (A) Myeloperoxidase (MPO)/H2O2/Cl (B) MPO/H2O2/NO2.* p < 0.05 vs Glut BP.

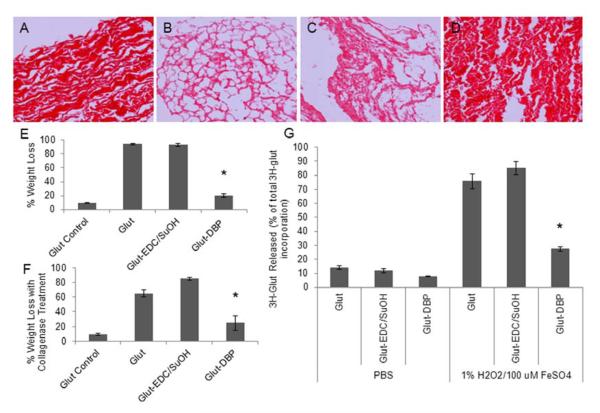

3.4 In vitro oxidation of BP and DBP modified BP

Oxidation of BP by a well-known oxidizing system (1% H2O2, 100 μM FeSO4) resulted in significant destruction of the collagen structure as shown by picrosirius red staining of collagen (Fig. 4B). In addition, oxidation caused significant mass loss of BP (Fig. 4E) as well as increased digestion by collagenase, 64.9 ± 4.9% for oxidized vs. 9.4 ± 1.7% for non-oxidized control (Fig. 4F). BP was cross-linked with 3H-glutaraldehyde to determine whether oxidizing conditions causes a loss of the glutaraldehyde cross-links. In PBS incubations over 7 days, the amount of 3H-glutaraldehyde released was 14.1 ± 1.3% of the total 3H-glutaraldehyde incorporated in the tissue, whereas with oxidation the loss was 75.7 ± 5.4% (Fig. 4G). These results indicate that BP is susceptible to oxidation and that this causes significant material degeneration.

Fig. 4. BHV oxidative damage in vitro is mitigated with DBP modification.

BP exposed to 1% H2O2/100 μM FeSO4 for 7 days. (A–D) Picrosirius red staining of collagen (200x magnification) (A) Glut BP no treatment (B) Glut BP oxidized (C) Glut-EDC/SuOH oxidized (D) Glut-DBP oxidized (E) Dry weight loss of oxidized BP (F) Collagenase treatment of oxidized BP (G) Stability of 3H-glutaraldehyde cross-linking in PBS and oxidizing conditions. *p < 0.05 vs Glut BP.

When exposed to the same oxidizing conditions, DBP modified BP had significantly less oxidative damage to the collagen structure than unmodified BP as shown by picrosirius red staining (Fig. 4A–D) and total mass loss, 20.2 ± 2.6% dry weight loss vs. 94.1 ± 0.8% (Fig. 4E). DBP modified BP was also less susceptible to digestion by collagenase than unmodified BP (p = 0.01) and had decreased release of 3H-glutaraldehyde than unmodified BP(p < 0.01). For all endpoints, the chemically treated BP control (Glut-EDC/SuOH) had no effect on preventing oxidative damage. These results indicate that the DBP modification mitigates oxidative damage of BP.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study provide a number of findings that demonstrate the susceptibility of BP to oxidation in both failed clinical BHV explants and experimental models. Clinical BHV are susceptible to oxidative stress, as indicated by elevated levels of oxidized amino acids. BP modified with the oxidant scavenger DBP was resistant to oxidative degradation in experimental models. Together these results suggest BHV structural degeneration may be due in part to oxidative modification, and that the use of the DBP modification utilized in the present studies may represent a therapeutic strategy to mitigate this significant clinical problem.

Oxidative modification of phenylalanine resulting in the formation of meta and ortho isomers of tyrosine have been used as biomarkers of oxidative stress [21, 22] and were significantly elevated in the clinical BHV explants. Dityrosine is formed through the oxidation of tyrosine residues and the formation of tyrosyl radicals. Dityrosine has been found to cross-link proteins and thus affects protein structure and function [21, 23, 24]. Photo-fixation for preparing clinical grade BHV has been attempted in the past by others; however, none of these BHV have proven to be suitable for clinical use [25, 26]. These prior efforts to induce photo-fixation crosslinks very likely resulted in the formation of dityrosine cross-links in BHV materials since photo-fixation as has been shown to form dityrosine [27]. However, based on the present clinical-explant results, dityrosine cross-links in BHV may disrupt normal collagen fiber organization, increasing matrix stiffness and contribute to valve failure through impaired mechanical function. Thus, oxidative modifications of BHV may both promote the formation of dityrosine protein cross-links, as quantified in the clinical BHV, which could mechanically impair leaflet function through an increase in material stiffness, as well as destabilize BHV leaflet durability due to the loss of glutaraldehyde crosslinks due to oxidation, as shown in our in vitro results. This combination of BHV cross-linking changes, loss of glutaraldehyde crosslinks and formation of dityrosine, could hypothetically affect the hemodynamic properties of the valve, resulting in clinical failure if function is impaired.

Since clinical BHV are subject to oxidative modification, it may be possible to mitigate this process through local delivery of an antioxidant. Local delivery of the oxidant scavenger DBP to BP was accomplished through covalent modification with carbodiimide activation of the carboxyl-containing amino acids in BP. DBP modified BP has scavenging activity against both ROS and RNS as demonstrated in experiments with the oxidation reporter Amplex Red, which demonstrates that the scavenging capacity of DBP is not affected by immobilization to BP.

Exposure to oxidants causes collagen damage in BP as demonstrated by the significant destruction of the collagen fibers, as well as mass loss and increased susceptibility to collagenase digestion. Previous studies have reported that after oxidation, collagen is more susceptible to degradation by proteolytic enzymes since oxidation causes collagen fragmentation, which can be more easily digested by proteolytic enzymes than intact collagen [16, 18]; these findings were confirmed in BP in the current study. Morphology studies of explanted clinical BHV have shown disruption in collagen organization [11, 12], which based on the current study, may be due to oxidative collagen damage.

An important material property of BHV is collagen cross-linking, which is accomplished with glutaraldehyde prior to clinical use. Exposure to oxidizing conditions results in the loss of glutaraldehyde cross-linking in BP. Previous studies have shown that rat subdermal implantation of glutaraldehyde treated BP have decreased glutaraldehyde content in explanted materials, which supports the findings of the current study [28, 29]. Glutaraldehyde is necessary for BHV because it confers both biomechanical stability over time and the stabilization of BP against proteolytic enzymes and other degradation; therefore loss of glutaraldehyde cross-linking following oxidation may be a significant cause of BHV structural degeneration.

The present studies provide a number of insights concerning the susceptibility of BHV to oxidative stress. However, these studies have a number of shortcomings that need to be addressed by future research. Our in vitro results and clinical-pathology analyses confirm oxidative modifications of BHV, but using different endpoints. The in vitro conditions used are accelerated, and the loss of massive amounts of BP material under the oxidizing conditions used precludes meaningful analyses of these materials for oxidized amino acids as were noted in the clinical explants. Similarly, the clinical pathology specimens available were all formalin fixed for processing as surgical pathology specimens. Formalin fixation permits mass spectrometry analyses for oxidized amino acids, but does permit assessing the other endpoints studied in vitro. Nevertheless, the results overall strongly support the view that BP BHV leaflets are susceptible to oxidative damage.

5. Conclusions

Clinical BHV are subject to oxidative modification. Covalent modification of the BHV material BP with DBP significantly prevented oxidative material damage in an experimental model of oxidative stress. Several effects of oxidative modification of BHV were identified in both clinical and experimental BP samples, including formation of dityrosine collagen cross-links, oxidative modifications of amino acids, loss of glutaraldehyde cross-links, collagen damage, and collagenase digestion. It is likely that all of these factors contribute to oxidation-mediated BHV structural degeneration. Additionally, since DBP was effective in reducing BHV oxidation, these studies suggest that BHV oxidation-mediated mechanisms may be prevented with local delivery of antioxidants.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: 5T32GM008076-29 (AJC predoctoral training grant in pharmacology), HL054926 (HI). Mass spectrometry studies were supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 HL076491 and performed on instruments housed in a facility partially supported through a Center of Excellence Agreement with AB SCIEX at the Cleveland Clinic. This research was also supported by a grant from the Cardiac Center of The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (AJC, RJL), The William J. Rashkind Endowment of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (RJL), and The Gisela and Dennis Alter Research Professor of Pediatrics (HI). The authors would like to thank Susan Kerns (The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia) for her assistance in submitting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kidane AG, Burriesci G, Cornejo P, Dooley A, Sarkar S, Bonhoeffer P, et al. Current developments and future prospects for heart valve replacement therapy. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2009;88:290–303. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pibarot P, Dumesnil JG. Prosthetic heart valves: selection of the optimal prosthesis and long-term management. Circulation. 2009;119:1034–48. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.778886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, Miller DC, Moses JW, Svensson LG, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siddiqui RF, Abraham JR, Butany J. Bioprosthetic heart valves: modes of failure. Histopathology. 2009;55:135–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoen FJ, Levy RJ. Calcification of tissue heart valve substitutes: progress toward understanding and prevention. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1072–80. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacks M, Schoen F. Collagen fiber disruption occurs independent of calcification in clinically explanted bioprosthetic heart valves. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;62:359–71. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simionescu A, Simionescu DT, Deac R. Biochemical pathways of tissue degeneration in bioprosthetic cardiac valves. ASAIO J. 1996;42:M561–7. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199609000-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gong G, Seifter E, Lyman W, Factor S, Blau S, Frater R. Bioprosthetic Cardiac Valve Degeneration Role of Inflammatory and Immune Reactions. J Heart Valve Dis. 1993;2:684–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shetty R, Pibarot P, Audet A, Janvier R, Dagenais F, Perron J, et al. Lipid-mediated inflammation and degeneration of bioprosthetic heart valves. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009 Jun;39:471–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Human P, Zilla P. Characterization of the immune response to valve bioprostheses and its role in primary tissue failure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:S385–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02492-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrans V, Spray T, Billingham M, Roberts W. Structural changes in glutaraldehyde-treated porcine heterografts used as substitute cardiac valves. Am J Cardiol. 1978;41:1159–84. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(78)90873-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spray T, Roberts W. Structural changes in porcine xenografts used as substitute cardiac valves. Am J Cardiol. 1977;40:319–30. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(77)90153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stachelek SJ, Alferiev I, Ueda M, Eckels EC, Gleason KT, Levy RJ. Prevention of polyurethane oxidative degradation with phenolic antioxidants covalently attached to the hard segments: structure-function relationships. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;94:751–9. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christenson EM, Anderson JM, Hiltner A. Oxidative mechanisms of poly(carbonate urethane) and poly(ether urethane) biodegradation: in vivo and in vitro correlations. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;70:245–55. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monboisse J, Borel J. Free Radicals and Aging. 1992. Oxidative damage to collagen; pp. 323–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curran S, Amoruso M, Goldstein B, Berg R. Degradation of soluble collagen by ozone or hydroxyl radicals. FEBS. 1984;176:155–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80931-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Au V, Madison SA. Effects of singlet oxygen on the extracellular matrix protein collagen: oxidation of the collagen crosslink histidinohydroxylysinonorleucine and histidine. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;384:133–42. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henrotin Y, Deberg M, Mathy-Hartert M, Deby-Dupont G. Biochemical Biomarkers of Oxidative Collagen Damage. Adv Clin Chem. 2009;49:31–55. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2423(09)49002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Citardi MJ, Song W, Batra PS, Lanza DC, Hazen SL. Characterization of oxidative pathways in chronic rhinosinusitis and sinonasal polyposis. Am J Rhinol. 2006;20:353–9. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2006.20.2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leeuwenburgh C, Rasmussen JE, Hsu FF, Mueller DM, Pennathur S, Heinecke JW. Mass Spectrometric Quantification of Markers for Protein Oxidation by Tyrosyl Radical, Copper, and Hydroxyl Radical in Low Density Lipoprotein Isolated from Human Atheroclerotic Plaques. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3520–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies SMK, Poliak A, Duncan MW, Smythe GA, Murphy MP. Measurements of protein carbonyls, ortho- and meta- tyrosine and oxidative phosphorylation complex activity in mitochondria from young and old rats. Free Radical Bio Med. 2001;31:181–90. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00576-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Souza JM, Giasson BI, Chen Q, Lee VM, Ischiropoulos H. Dityrosine cross-linking promotes formation of stable alpha -synuclein polymers. Implication of nitrative and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative synucleinopathies. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18344–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balasubramanian D, Kanwar R. Molecular pathology of dityrosine cross-links in proteins: structural and functional analysis of four proteins. Mol Cell Biochem. 2002;234/235:27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meuris B, Phillips R, Moore MA, Flameng W. Porcine stentless bioprostheses: prevention of aortic wall calcification by dye-mediated photo-oxidation. Artif Organs. 2003;27:537–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2003.07108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verbrugghe P, Meuris B, Flameng W, Herijgers P. Reconstruction of atrioventricular valves with photo-oxidized bovine pericardium. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9:775–9. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2008.200097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vashi AV, Werkmeister JA, Vuocolo T, Elvin CM, Ramshaw JA. Stabilization of collagen tissues by photocrosslinking. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2012;100:2239–43. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Webb CL, Benedict JJ, Schoen FJ, Linden JA, Levy RJ. Inhibition of Bioprosthetic Heart Valve Calcification with Aminodiphosphonate Covalently Bound to Residual Aldehyde Groups. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;46:309–16. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)65932-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Golomb G, Schoen FJ, Smith M, Linden J, Dixon M, Levy RJ. The role of glutaraldehyde-induced cross-links in calcification of bovine pericardium used in cardiac valve bioprostheses. Am J Pathol. 1987;127:122–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]