Abstract

Background: The purpose of this study was to measure the level of quality of work life (QWL) among hospital employees in Iran. Additionally, it aimed to identify the factors that are critical to employees’ QWL. It also aimed to test a theoretical model of the relationship between employees’ QWL and their intention to leave the organization.

Methods: A survey study was conducted based on a sample of 608 hospital employees using a validated questionnaire. Face, content and construct validity were conducted on the survey instrument.

Results: Hospital employees reported low QWL. Employees were least satisfied with pay, benefits, job promotion, and management support. The most important predictor of QWL was management support, followed by job proud, job security and job stress. An inverse relationship was found between employees QWL and their turnover intention.

Conclusion: This study empirically examined the relationships between employees’ QWL and their turnover intention. Managers can take appropriate actions to improve employees’ QWL and subsequently reduce employees’ turnover.

Keywords: Quality of Working Life, Turnover Intention, Human Resource Management, Hospital

Background

Competent, committed and motivated employees are keys to delivery of quality services in healthcare organizations. A more attractive environment and a high quality of work life (QWL) are critical to attract and retain qualified healthcare professionals. Quality of work life refers to an employee’s satisfaction with the working life. It emphasises the quality of the relationship between the worker and the working environment (1). Quality of work life is a multi-dimensional concept. It covers employees’ feelings about the job content, the physical work environment, pay, benefits, promotions, autonomy, teamwork, participation in decision-making, occupational health and safety, job security, communication, colleagues and managers support and work-life balance (2-7).

Quality of work life provides employees with the motivation to perform well (8). Improving employees’ QWL is a prerequisite to increase their productivity. Positive results of QWL include reduced burnout (9), reduced absenteeism (10), lower turnover (11), improved job satisfaction (12) and organizational commitment (13). QWL enhances employees’ dignity through job satisfaction and humanising the work by assigning meaningful jobs, giving opportunities to develop human capacity to perform well, ensuring job security, adequate pay and benefits, and providing safe and healthy working conditions (2,14). As a result, high QWL organizations may enjoy better sustainable efficiency, productivity and profitability (7,15).

Very little research in the literature is available on the link between employees’ QWL and their turnover intention (11). Most of these studies have been based on data collected in Western countries and limited to health care employees. This study aims to overcome this gap by investigating these variables in a group of hospitals in Iran. There are no known studies related to the links between these subjects in the health care organizations of the country.

Iran is an Islamic society with a distinctive culture due to its unique historical, racial and religious identities. For instance, Iran according to Hofstede’s cross-cultural dimensions highly scored on ‘power distance’ and ‘uncertainty avoidance’ (16). A culture of high power distance and uncertainty avoidance promotes mechanistic and hierarchical structures, centralised decision-making, dependency on superiors and a preference for clear rules and regulations for every situation. Managers in such a culture do not provide job enrichment and empowerment and employees do not necessarily want the responsibilities (17).

In nations high on individualism such as Iran (18,19), individual decisions are thought to be better than group decisions. People in such a culture emphasise individual initiative and achievement. Iranians are more “feminine” (16). They do care about people surrounding them. People in such a society are more emotional and less tolerant of opinions different from what they are used to. Relationships with co-workers, employment security and a friendly atmosphere are relatively more important than recognition, advancement and challenge in such a society. Iranians are more short-term thinkers. They emphasise more on quick results and benefits (20).

The results of this research will allow a better understanding of the impact of employees’ QWL on their turnover intention. The results also, will enhance our understanding of the determinants of QWL in an Islamic and developing country. It is anticipated that a better understanding of these issues and their relationships can aid further research, pinpoint better strategies for recruiting, promotion, and training of future hospital employees, particularly in Iran but perhaps in other societies as well.

Literature review

Employee turnover is an employee’s voluntary withdrawal from the organization (21). Turnover of skilled and professional healthcare staff can incur substantial costs for organizations. Recruiting and training new employees are very costly for organizations. High staff turnover can also influence negatively an organization’s capacity to meet patient needs and provide quality healthcare services (22,23). Employees’ behavioural intention to turnover is a predictor of their actual turnover (24). Turnover intention may be an indicator of low QWL.

Some studies found a positive relationship between employees’ QWL and their job satisfaction (1,25). Low employees’ job satisfaction is a significant predictor of their turnover intention (26-28). Other empirical studies confirm the important role of organizational commitment in the turnover process (27,29). Demographic variables such as age and tenure were also reported as employees’ turnover predictors (30).

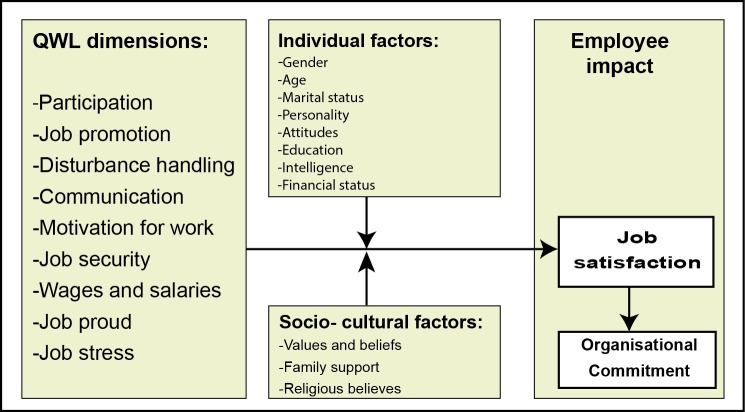

Nevertheless, the role of QWL in employee turnover has not been well investigated. The proposed framework presented at Figure 1 aims to explain the relationship between employees’ QWL and their turnover intention. It is anticipated that improving employees’ QWL, increases their job satisfaction and subsequently their organizational commitment. As a result, employees’ intention to leave the organization will be decreased.

Figure1 .

Hypothesized relationship between QWL and turnover intention

This survey investigates possible relationships between QWL and employees’ turnover intention. This study also focuses on revealing demographic variables that influences employees’ QWL and turnover intention. Examining the impact of other variables shown in Figure 1 on employees’ turnover intention is beyond the focus of this study.

Methods

Purpose and objectives

The main purpose of this study was to determine the level of QWL among hospital employees in Isfahan, Iran. It also aimed to explore the relationship between QWL and turnover intention among hospital employees. Doing so has practical relevance for designing and implementing strategies and interventions to improve QWL among hospital employees.

Design

The study utilised cross-sectional, descriptive and co-relational design and survey methodology.

Setting

Hospital care in Iran is provided by a network of regional hospitals located in the main cities. This includes government financed Ministry of Health hospitals (MOH), the Social Security Organization (SSO) affiliated hospitals and private hospitals. The study was carried out at six hospitals, three MOH (two educational and one non educational), one SSO and two private hospitals. The six hospitals of the study were selected to represent the three dominant hospital care systems in Iran.

Population and sample

Seven hundred and forty employees were selected for this research after a pilot study by using the following formula (n=2411, d=0.03, z=1.96 and s=0.50). Employees who had less than 6 months working experience were excluded from this study.

Instrument

The items of QWL questionnaire were gathered by means of a literature review (31-34) and a Delphi method. In total, nine dimensions of QWL were defined (Table 1). This questionnaire has 36 items (four items in each dimension). Ratings were completed on a five-point scale (from very low=1 to very high=5). Turnover intention was measured using a single item: “To what extent do you want to leave this organization, if you find another job opportunity?”

Table 1. Internal consistency analysis .

| Constructs | Item Numbers | Number of Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

| Participation and Involvement | 1,10,19,28 | 4 | 0.81 |

| Job Promotion | 2,11,20,29 | 4 | 0.78 |

| Disturbance Handling | 3,12,21,30 | 4 | 0.82 |

| Communication | 4,13,22,31 | 4 | 0.76 |

| Motivation for Work | 5,14,23,32 | 4 | 0.71 |

| Job Security | 6,15,24,33 | 4 | 0.72 |

| Wages and Salaries | 7,16,25,34 | 4 | 0.76 |

| Job Proud | 8,17,26,35 | 4 | 0.73 |

| Job Stress | 9,18,27,36 | 4 | 0.77 |

| Overall QWL | 1-36 | 36 | 0.91 |

Dependent and independent variables

Employee’s turnover intention was the dependent variable in this study. Independent variables included nine dimensions of QWL (i.e., Participation and involvement, job promotion, disturbance handling, communication, motivation for work, job security, wages and salaries, job proud, and job stress).

Pilot study

A pilot study was undertaken to test the relevance and clarity of the questions and to refine them as needed to avoid misunderstanding. A small sample of forty of randomly selected hospital employees who were not included in the sample was received the questionnaires. The questionnaires were found to be understandable and acceptable.

Validity of the research instruments

In this research, nine QWL constructs have content validity since they were derived from an extensive review of the literature, and evaluations by academics and practitioners.

Reliability of the research instrument

Cronbach’s alpha was computed for each scale using the SPSS 11 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The reliability coefficient was 0.91 for QWL questionnaire (Table 1).

Data collection

A stratified random sampling method was employed in this study. Data collection was undertaken in September 2008. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects following receipt of information on the purpose of the study, assurances of anonymity and confidentiality.

Data analysis

All data were analysed using the SPSS 11 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). In order to normalize the Likert scale on 1-5 scales for each domain of QWL questionnaire, the sum of raw scores of items in each domain was divided by the numbers of items in each domain (4 items) and for overall QWL, sum of raw scores of items were divided by 36 respectively. The possible justified scores were varied between 1 and 5. Scores of 2 or lower on the total scale indicate very low, scores between 2 and 2.75 indicate low, scores between 2.76 and 3.50 indicate moderate, scores between 3.51 and 4.25 indicate high and scores of 4.26 or higher indicate very high QWL.

The differences between groups were tested with the chi-squared test, in-dependent t-Test, Mann-Whitney and Kruskal Wallis tests. Then, the relationship between QWL and turnover intention was investigated by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients. Regression analysis was used to identify the most important predictor domains in QWL. The significance level was set at P<0.05.

Results

Six hundred and eight employees completed the questionnaires (82.20%). The characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 2. More than half of the respondents were females and over three fourths were married. They had mostly at least a college degree. More than half of the employees had incomes of less than 3,000,000 Rials (poverty line in Iran in 2008). 48.70% of employees had permanent employment. The age of these hospital employees ranged from 21 to 60, with an average age of 34.53 ± 8.28 (Mean ± SD). Over half (67%) is less than 40 years old. Employees on the average had 10.80 years of working experiences respectively.

Table 2. Percentage of participants and the mean score of their QWL .

| Demographic Parameters | Percent of Sample | QWL | |

| Mean | SD | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 45.70 | 2.60 | 0.51 |

| Female | 54.30 | 2.49 | 0.52 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 19.40 | 2.47 | 0.52 |

| Married | 80.60 | 2.56 | 0.51 |

| Education | |||

| Illiterate | 0.70 | 2.53 | 0.44 |

| Under Diploma | 14.00 | 2.66 | 0.47 |

| Diploma | 19.90 | 2.62 | 0.43 |

| Post Diploma | 15.80 | 2.46 | 0.49 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 45.40 | 2.50 | 0.48 |

| Master’s Degree or GP | 3.60 | 2.46 | 0.56 |

| Doctoral Degree | 0.70 | 2.33 | 0.41 |

| Area of Work | |||

| Managerial and Clerical | 12.00 | 2.74 | 0.44 |

| Ancillary or Logistic | 19.40 | 2.65 | 0.45 |

| Diagnostic | 17.10 | 2.53 | 0.55 |

| Therapeutic | 51.50 | 2.46 | 0.53 |

| Age (years) | |||

| 20-30 | 34.40 | 2.49 | 0.52 |

| 31-40 | 32.60 | 2.57 | 0.53 |

| 41-50 | 29.10 | 2.55 | 0.46 |

| >50 | 3.90 | 2.64 | 0.57 |

| Tenure (years) | |||

| 1-5 | 32.90 | 2.51 | 0.54 |

| 6-10 | 26.00 | 2.54 | 0.54 |

| 11-15 | 15.10 | 2.58 | 0.56 |

| 16-20 | 11.20 | 2.52 | 0.43 |

| 21-25 | 7.60 | 2.50 | 0.50 |

| 26-30 | 6.90 | 2.63 | 0.48 |

| >30 | 0.30 | 2.76 | 0.62 |

| Type of Employment | |||

| Contract | 51.30 | 2.58 | 0.53 |

| Permanent | 48.70 | 2.50 | 0.51 |

| Received Wages | |||

| <3,000,000 RLS | 58.40 | 2.48 | 0.52 |

| >3,000,000 RLS | 41.60 | 2.63 | 0.51 |

The mean score of employees QWL was 2.53 on a five scale implying that overall the level of QWL was low. The overall scores ranged from 1.47 to 4.45 (possible range 1-5). QWL was very low, low, medium, high and very high in 16.10, 53.90, 25.20, 4.60 and 0.20% of hospital employees.

In correlation analysis between QWL and its nine dimensions, disturbance handling (management support), job proud, job security, job stress and participation and involvement respectively had the highest effect on employees’ QWL. The results of the stepwise regression model indicate that 89% of the variance in overall QWL is explained by disturbance handling (management support), job proud, and job security. The variables-resolving organizational and job related problems of employees, using employees’ suggestion and ideas in resolving organizational problems, good relations between employees and managers, employees’ proud about working in the organization, fair job promotion, job security, fringe benefits and job stress were the most influential factor in QWL.

Organizational factors explained the largest amount of the variance in employees’ QWL (26.20%), followed by individual factors such as education and marital status. There was strong correlation between QWL of employees and their gender, marital status, organizational position, and education level (P<0.05). Those who were married had a higher level of QWL as compared to the singles. A statistical significant association was not found between employees’ QWL and their area of work (P=0.76).

The Kruskal Wallis test revealed that the total QWL scores was differed among six hospitals (Chi squared =30.29, df=5, P<0.001). Employees’ QWL in private hospitals was less than public and semi public hospitals (see Table 3). However, the differences between values of employees QWL in these hospitals were not statistically significant (P>0.05).

Table 3. The mean of employees’ QWL in different hospitals (on a 5 scale) .

| QWL Dimensions | Public Hospital | Semi Public Hospital | Private Hospital | Over all | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Participation & Involvement | 2.38 | 0.80 | 2.20 | 0.70 | 2.28 | 0.84 | 2.32 | 0.80 |

| Job Promotion | 2.23 | 0.81 | 2.13 | 0.69 | 2.07 | 0.71 | 2.17 | 0.76 |

| Disturbance Handling | 2.34 | 0.71 | 2.16 | 0.60 | 2.18 | 0.73 | 2.27 | 0.70 |

| Communication | 2.81 | 0.84 | 2.62 | 0.79 | 2.88 | 0.83 | 2.80 | 0.76 |

| Motivation for Work | 3.25 | 0.74 | 3.36 | 0.75 | 3.31 | 0.81 | 3.28 | 0.67 |

| Job Security | 2.77 | 0.79 | 2.59 | 0.67 | 2.55 | 0.80 | 2.68 | 0.68 |

| Wages and Salaries | 1.97 | 0.76 | 2.34 | 0.81 | 1.88 | 0.73 | 2.01 | 0.70 |

| Job Proud | 2.63 | 0.71 | 2.84 | 0.68 | 2.57 | 0.72 | 2.65 | 0.71 |

| Job Stress | 2.71 | 0.89 | 2.76 | 0.89 | 2.49 | 0.92 | 2.66 | 0.89 |

| Overall QWL | 2.56 | 0.53 | 2.55 | 0.45 | 2.47 | 0.53 | 2.53 | 0.52 |

Managers registered a statistically significant higher level of quality of working life than employees (t=-1.99 and P=0.04). They experienced more job proud, job promotion, and job security, felt more supported by top management and were involved more in the management of their organizations (see Table 4). As a result, they were more motivated than their staff. Employees were more likely than managers to be dissatisfied with their promotion, wages and salaries.

Table 4. The mean of employees and managers’ QWL (on a 5 scale) .

| QWL Dimensions | Managers | Employees | P | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Participation & Involvement | 2.48 | 0.84 | 2.28 | 0.78 | >0.001 |

| Job Promotion | 2.39 | 0.77 | 2.12 | 0.75 | >0.001 |

| Disturbance Handling | 2.49 | 0.76 | 2.22 | 0.69 | >0.001 |

| Communication | 2.91 | 0.90 | 2.78 | 0.84 | 0.06 |

| Motivation for Work | 3.46 | 0.81 | 3.24 | 0.75 | >0.001 |

| Job Security | 2.85 | 0.90 | 2.64 | 0.76 | 0.03 |

| Wages and Salaries | 2.10 | 0.84 | 1.99 | 0.79 | 0.16 |

| Job Proud | 2.86 | 0.65 | 2.60 | 0.72 | 0.01 |

| Job Stress | 2.71 | 0.94 | 2.65 | 0.91 | 0.70 |

| Overall QWL | 2.69 | 0.53 | 2.50 | 0.52 | >0.001 |

Employees’ QWL in administrative (2.44) and therapeutic (2.51) departments was lower than diagnostic (2.55) and ancillary (2.68) departments. The differences between values were statistically significant (P=0.02). The mean score of employees’ QWL in the quality improvement office (3.01), catering (2.82), physiotherapy (2.74), and pharmacy (2.72) was high and in internal medicine ward (1.99), surgery ward (2.20), medical records department (2.21); Intensive Care Unit (2.36), and E & A ward (2.44) was low.

When asked whether they would leave their organization, if they find another job opportunity, 40.40% of hospital employees responded that they would leave their organization if they find another job opportunity. QWL was negatively (r=-0.44 and P<0.001) associated with turnover intentions (see Table 5). QWL was positively (r=-0.54 and P<0.001) associated with recommending the organization to others for work. QWL was a major contributor to employee turnover intention. Regression analysis of data indicated that predictors of intent to leave were low motivation, organizational policies, job stress, poor communication, and lack of job security.

Table 5. inter-correlations between job stress and QWL .

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| 1. Overall QWL | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Participation & Involvement | 0.7** | - | |||||||||

| 3. Job Promotion | 0.77** | 0.57** | - | ||||||||

| 4. Disturbance Handling | 0.71** | 0.59** | 0.67** | - | . | ||||||

| 5. Communication | 0.67** | 0.56** | 0.47** | 0.48** | - | ||||||

| 6. Motivation for Work | 0.49** | 0.21** | 0.30** | 0.27** | 0.24** | - | |||||

| 7. Job Security | 0.71** | 0.53** | 0.47** | 0.42** | 0.47** | 0.23** | - | ||||

| 8. Wages and Salaries | 0.61** | 0.43** | 0.45** | 0.28** | 0.22** | 0.24** | 0.388** | - | |||

| 9. Job Proud | 0.69** | 0.45** | 0.47** | 0.44** | 0.36** | 0.42** | 0.336** | 0.453** | - | ||

| 10. Job Stress | -0.47** | -0.28** | -0.20** | -0.19** | -0.11** | -0.11** | -0.313** | -0.177** | -0.149** | - | |

| 11. Intention to Leave | -0.44** | -0.21** | -0.27** | -0.21** | -0.15** | -0.74** | -0.273** | -0.259** | -0.308** | 0.184** | - |

|

12. Recommending Hospital to others for Work |

0.54** | 0.33** | 0.47** | 0.34** | 0.29** | 0.33** | 0.294** | 0.481** | 0.704** | -0.171** | -0.292** |

|

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed) | |||||||||||

Significant relationships were found between employees’ turnover intention and their age (P<0.001), tenure (P<0.001) and marital status (P=0.03) and type of employment (P=0.05). An inverse relationship between employees’ education level and turnover intention was found in this study. Employees in lower educational background were less satisfied with pay and more likely to leave. Temporary and casual employees were more likely to leave their hospitals than fulltime permanent staff.

Discussion

This study set out to assess the degree of QWL among Iranian hospital employees. Hospital employees reported low levels of QWL. Management support and security of employment exhibited the most direct effects on employees’ QWL. These findings are consistent with other similar studies in Iranian healthcare context (35). They also found that employees were more dissatisfied with management support, poor communication, payment and working conditions. Similarly, Lewis and colleagues in a study of the health-care settings in the south central region of Ontario, Canada found that pay, benefits and supervisor style play the major role in determining employees’ QWL satisfaction (6).

This study showed that employees who worked in private hospitals had lower QWL. They were more dissatisfied with their career prospects, pay, benefit, workload and job security. Job insecurity negatively influenced QWL of hospital employees. Job security is an important determinant of employees’ job satisfaction (27). Increased workloads and financial restraint has left employees feeling increased pressure in their jobs. Hospital managers should enhance employees’ QWL through improving their working conditions and providing fair promotion and benefits.

Employees’ QWL is also related to the quality of management and leadership of the organization. Management support and employees’ experience of fair treatment by management is positively related to employees’ job satisfaction (36-38) and quality of work life (8,39). Lack of control, autonomy, and participation in decision-making are negatively linked with employees’ QWL and may result in employees’ turnover. Managers should develop and communicate corporate vision, goals and values, create high quality work environments, provide more training and promotion opportunities, involve employees in decision-makings and pay them fairly and adequately.

The current study showed that promotion opportunities were another significant predictor of QWL. Unfair promotion policies perceived by employees may negatively affect their QWL. Dissatisfaction with promotion opportunities has been shown to have a stronger impact on employees’ turnover. These finding is consistent with the findings of other researchers (23,40). Employees should be considered as developing human assets. Life-long learning, professional growth and advancement promote employees’ job satisfaction, and enable continued provision of high-quality healthcare services (41,42). Managers must be supportive and give employees opportunities for advancement.

Salary and fringe benefits are also correlated with employees’ QWL and turnover intention. Employees may leave their organizations for higher salary. Besides, the fairness of an organization’s compensation system is important for employees. Employees who feel a fair compensation system that rightfully rewards their efforts have less intention to leave their organization (11).

The results show that occupational stress is negatively associated with employees’ QWL. Employees who were least satisfied with pay, promotion, job security, participation in decision making tended to experience higher levels of occupational stress. Occupational stressors may have harmful effects on an individual’s physical (43,44) as well as mental and emotional health (45,46). High levels of occupational stress have been linked to high staff absenteeism and low levels of productivity (47). Occupational stress is also negatively related to quality of care (48). A strong inverse relationship was found between employees’ occupational stress and their job satisfaction (49,50), organizational commitment (51,52) and intentions to leave (53,54). According to the current study, employees at semi public hospitals reported higher occupational stress. Semi-public hospitals provide free of charge healthcare services to social security insured patients. Consequently, the demand for services in these hospitals is very high. Thus, employees at these hospitals experience more duty related stress. Managers were also more likely than employees to experience occupational stress.

Jobs should be designed in ways that provide meaning, motivation, and opportunities for employees to use their skills. Managers can apply techniques such as job enlargement, job enrichment, and job rotation to improve employees’ satisfaction and productivity. Workload should be is in line with employees’ capabilities and resources. Increased workloads may deteriorate employees’ QWL (32). Employees’ roles and responsibilities should be clearly defined. They should be given opportunities to participate in decisions and actions affecting their jobs.

This study revealed a reverse relationship existing between QWL and turnover intention. Improving employees’ QWL will ultimately lead to increased job satisfaction and reduced turnover intention among employees. It is recommended that particular attention be given to improving employees’ attitudes and morale through organizational change programmes. The results of this study suggest that management might be able to improve the level of QWL in the organization by increasing employees’ satisfaction with organizational policies, work conditions, equal compensation and equal promotion. Changes in management systems and structure, changes in senior management behaviour, changes in organizational variables, such as benefit scales, employee involvement and participation in policy development, and work environment, and demonstrating value to staff could then be made in an effort to increase employees’ QWL and decrease subsequent turnover.

Although recruiting more staff and increased compensation and benefits offset hospital staff dissatisfaction in the short term, improving employees’ QWL would be a more long-term practical approach to improving hospital staff retention and reducing turnover. However, the success of QWL programmes depends on organizational culture and partnership between management and employees. The goal of QWL programmes is to improve the work design and requirements, the working conditions and environment and organizational effectiveness. It aims to create more involving, satisfying and effective jobs and work environment for employees at all levels of the organization. A decentralized organizational structure, a commitment to flexible working hours, an emphasis on professional autonomy, and improved communication between management and employees result in higher levels of employee job satisfaction and lower turnover.

Employee’s involvement and cooperation is a key factor in the success of QWL. Empowered employees have more autonomy and control over their work conditions and as a result are more likely to have higher job satisfaction and organizational commitment, and lower job stress and burnout (55,56). However, introduction and implementation of QWL programmes involving greater employees’ participation and involvement in the decision-making process may pose difficulties in countries where there is a greater power distance and separation of management and employee roles. Such programmes would probably meet with resistance from those people who would be adversely affected. Iran scored high on power distance index (16,57,58). Iranian managers might be somewhat reluctant to accept changes in their subordinates’ and their own job responsibilities where this change meant a reduced power distance. Therefore, any attempt to apply participative management techniques in Iranian context should be adjusted. QWL efforts will require innovative thinking to construct a unique stance regarding the involvement of the employee in the decision-making process in light to the power distance in the culture.

The particular QWL approach in various cultures, in respect of formality and rule-orientation, might also vary with the level of uncertainty avoidance (59). QWL programmes involve change. These changes will be resisted by people in cultures characterised by a high uncertainty avoidance index. Therefore, in countries with high uncertainty avoidance like Iran (16) adequate rules and regulations are required to provide structure and certainty in the changing conditions created by QWL programmes. This assures that the employees are not overwhelmed with anxiety.

When introducing QWL to various cultures, attention must be also given to the relative individual versus collective emphasis. Organizations operating in countries low on individualism may tend to deemphasise individual incentives and rewards and prefer to provide group incentives and opportunities for group problem-solving. In such countries with low individualism, organizational QWL programmes are likely to be group oriented and somewhat paternalistic in flavour. However, in nations high on individualism such as Iran (18,19,60), individual decisions are thought to be better than group decisions and as a result individual initiative is socially encouraged, and a strong importance is attached to freedom and challenge in jobs.

The implementation of QWL often leads to changes in the nature of work to increase job meaning and therefore employee motivation and satisfaction. Techniques such as job rotation (alternating task assignments), job enlargement (expanding the scope of the job by adding more task variety) and job enrichment (expanding the depth of the job by adding more responsibility and authority) are examples of job redesign interventions to improve employee satisfaction. However, QWL intervention must be cognizant of the degree to which any work changes are seen as interfering with personal areas of people’s lives (59). Iran scored considerably lower on the Hofstede masculinity/femininity index (16). Hofstede indicated that in more masculine cultures, humanised jobs should provide more opportunities for recognition, advancement, and challenge whereas in less masculine cultures, the emphasis would be more on cooperation and good working atmosphere (16). Thus, in lower masculine countries, organizations should not interfere with the private lives of their employees, whereas in higher masculine countries this interference in private lives is seen to be more legitimate.

Conclusion

In a cross sectional study, the level of employees’ QWL among a group of hospital employees in Iranian hospitals was measured. The hospital employees’ QWL was low. Factors that influenced employees’ QWL in this study were demographic variables of gender, graduation level, place of work, type of employment, and the nine dimensions of QWL as indicted in Table 1. Poor treatment by managers, dissatisfaction with job security and career prospects, and a perception that pay was not sufficient and fair were the main reasons for employees’ low QWL. Employees who experienced lower QWL had more intention to leave their organization, if they find another job opportunity.

Theoretical implications

This study makes several distinct contributions. First, using a cross sectional approach, the level of QWL among a group of hospital employees in Iranian hospitals were examined. Second, factors contributing to employees’ QWL were identified. Third, the relationship between employees’ QWL and their turnover intention was examined.

Managerial implications

There are several practical implications that can be derived from the findings. Healthcare managers should be encouraged to monitor employees’ QWL and improve it by applying the right human resources polices. The most contributor to employees QWL in this study were lack of management support, lack of job security, inadequate pay, inequality at work, too much work, staff shortages, and lack of recognition and promotion prospects. Organizational factors were the main predictors of employees’ QWL. Hospital managers and policy makers must manage these organizational variables more constructively to enhance employees’ QWL and subsequently performance. They should try to satisfy both employees’ work and personal needs.

Limitations and implications for future research

The findings should be interpreted with caution since the participants were employees from six hospitals in Iran. More research in this area is needed before generalizing the study findings. The cross-sectional nature of the research limits inferences concerning causality between QWL and turnover intention. The optimal approach would be longitudinal studies to detect changes in employees’ turnover intention due to changes in their QWL. Interviews with employees on factors influencing their QWL and turnover intention would be also useful.

Citation: Mosadeghrad AM. Quality of working life: An antecedent to employee turnover intention. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 2013; 1: 43-50.

Footnotes

Ethical issues

The main ethical issues involved in this study were respondents’ rights to self-determination, anonymity and confidentiality. For this reason, respondents were given full information on the nature of the study through a letter, which was distributed with the questionnaire. The questionnaire data were kept confidentially and respondents were assured of their right to withdraw at any time. The names of the respondents were not recorded and so all the data were rendered anonymous.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Author’s contribution

AMM is the single author of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Raduan CR, LooSee B, Jegak U, Khairuddin I. Quality of Work Life: Implications of Career Dimensions. Journal of Social Sciences. 2006;2:61–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adhikari DR, Gautam DK. Labour legislations for improving quality of work life in Nepal. International Journal of Law and Management. 2010;52:40–53. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connell J. Call centres, quality of work life and HRM practices: An in-house/outsourced comparison. Employee Relations. 2009;31:363–81. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallie D. Employment regimes and the quality of work. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu MY, Kernohan G. Dimensions of hospital nurses’ quality of working life. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54:120–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis D, Brazil K, Krueger P, Lohfeld L, Tjam E. Extrinsic and intrinsic determinants of quality of work life. Leadership in Health Services. 2001;14:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau RS. Quality of work life and performance. International Journal of Service Industry Management. 2000;11:422–37. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dolan SL, García S, Cabezas C, Tzafrir SS. Predictors of quality of work and poor health among primary health-care personnel in Catalonia: Evidence based on cross-sectional, retrospective and longitudinal design. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2008;21:203–18. doi: 10.1108/09526860810859058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuuli P, Karisalmi S. Impact of working life quality on burnout. Exp Aging Res. 1999;25:441–9. doi: 10.1080/036107399243922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donaldson SI, Sussman S, Dent CW, Severson HH, Stoddard JL. Health behavior, quality of work life, and organizational effectiveness in the lumber industry. Health Educ Behav. 1999;26:579–91. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korunka C, Hoonakker P, Carayon P. Quality of Working Life and Turnover Intention in Information Technology Work. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing. 2008;18:409–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Havlovic SJ. Quality of work life and human outcomes. Industrial Relations. 1991;30:469–79. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daud N. Investigating the Relationship between Quality of Work Life and Organizational Commitment amongst employees in Malaysian firms. International Journal of Business and Management. 2010;5:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hian CC, Einstein WO. Quality of work life: what can unions do? Advanced Management Journal. 1990;55:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.May BE, Lau RSM, Johnson SK. A longitudinal study of quality of work life and business performance. South Dakota Business Review. 1999;58:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aycan Z, Kanungo RN, Mendonca M, Yu K, Deller J, Stahl G. et al. Impact of Culture on Human Resource Management Practices: A 10-Country Comparison. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2001;49:192–221. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hadizadeh Moghadam A, Assar P. The Relationship between national culture and E-adoption: A case study of Iran. American Journal of Applied Sciences. 2008;5:369–77. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nasiri Pour AA, Mehr-El Hasani MH, Gorji A. Relationship between organisational culture and Six sigma implementation in Kerman university hospitals. Health Manage Q. 2008;11:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabasakal H, Dastmalchian A. Introduction to the special issue on leadership and culture in the Middle East. An International Review. 2001;50 [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Croon EM, Sluiter JK, Blonk RW, Broersen JP, Frings-Dresen MH. Stressful Work, Psychological Job Strain, and Turnover: A 2-Year Prospective Cohort Study of Truck Drivers. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89:442–54. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray AM, Phillips VL. Labour turnover in the British National Health Service: a local labour market analysis. Health Policy. 1996;36 :273–89. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00818-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shields MA, Ward M. Improving nurse retention in the National Health Service in England: the impact of job satisfaction on intentions to quit. J Health Econ. 2001;20:677–701. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parasuraman S. Predicting turnover intentions and turnover behaviour: A multivariate analysis. J Vocat Behav. 1982;21:111–21. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Che Rose R, Beh LS, Uli J, Idris K. Quality of Work Life: Implications Of Career Dimensions. Journal of Social Sciences. 2006;2:61–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griffeth R, Hom P, Gaertner S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management. 2000;26:463–88. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosadeghrad AM, Ferlie E, Rosenberg D. A Study of relationship between Job satisfaction, Organizational commitment and turnover intention among hospital employees. Health Serv Manage Res. 2008;21:211–27. doi: 10.1258/hsmr.2007.007015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin JT, Yang KA. Nursing turnover in Taiwan: a meta-analysis of related factors. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39:573–81. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(01)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sjoberg A, Sverke M. The interactive effect of job involvement and organizational commitment on job turnover revisited: A note on mediating role of turnover intention. Scand J Psychol. 2000;41:247–52. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tai TWC, Bame SI, Robinson CD. Review of nursing turnover research, 1977–1996. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1905–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole DC, Robson LS, Lemieux-Charles L, McGuire W, Sicotte C, Champagne F. Quality of working life indicators in Canadian health care organizations: A tool for healthy health care workplaces. Occup Med. 2005;55:54–9. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqi009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gifford BD, Zammuto RF, Goodman EA. The relationship between hospital unit culture and nurses’ quality of work life. Journal of Health Care Management. 2002;47:13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilgeous V. Manufacturing managers: their quality of working life. Integrated Manufacturing Systems. 1998;9:173–81. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yousuf AS. Evaluating the quality of work life. Management and Labour Studies. 1996;21:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dargahi H, Sharifi Yazdi MK. Quality of Work Life in Tehran University of Medical Sciences hospitals’ Clinical Laboratories employees. Pak J Med Sci. 2007;23:630–3. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baruch-Feldman C, Brondolo E, Ben-Dayan D, Schwartz J. Sources of social support and burnout, job satisfaction, and productivity. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7:84–93. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.7.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mosadeghrad AM, Yarmohammadian MH. A study of relationship between managers’ leadership style and employees’ job satisfaction. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv. 2006;19:xi–xxviii. doi: 10.1108/13660750610665008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosadeghrad AM, Ferdosi M. Leadership, job satisfaction and organizational commitment in healthcare sector: Proposing and testing a model. Mat Soc Med. 2013;25:121–6. doi: 10.5455/msm.2013.25.121-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boumans NPG, Landeweerd JA, Visser M. Differentiated practice, patient-oriented care and quality of work in a hospital in The Netherlands. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004;18:37–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2004.00253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davidson H, Folcarelli PH, Crawford S, Duprat LJ, Clifford JC. The effects of health care reforms on job satisfaction and voluntary turnover among hospital based nurses. Med Care. 1997;35:634–45. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199706000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Donner GJ, Wheeler MM. Career planning and development for nurses: The time has come. Int Nurs Rev. 2001;48:79–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2001.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kennington G. A case for a formalized career development policy in orthopaedic nursing. Journal of Orthopaedic Nursing. 1999;3:33–8. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Espnes GA, Byrne DG. Occupational stress and cardiovascular disease. Stress Health. 2008;24:231–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang MG, Koh SB, Cha BS, Park JK, Baik SK, Chang SJ. Job stress and cardiovascular risk factors in male workers. Prev Med. 2005;40:583–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cho JJ, Kim JY, Chang SJ, Fiedler N, Koh SB, Crabtree BF. et al. Occupational stress and depression in Korean employees. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;82:47–57. doi: 10.1007/s00420-008-0306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’connor DB, O’connor RC, White BL, Bundred PE. The effect of job strain on British general practitioners’ mental health. J Ment Health. 2000;9:637–54. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reynolds S. Psychological well-being at work: Is prevention better than cure? J Psychosom Res. 1997;43:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leveck ML, Jones CB. The nursing practice environment, staff retention, and quality of care. Res Nurs Health. 1996;19:331–43. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199608)19:4<331::AID-NUR7>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahsan N, Abdullah Z, Yong Gun Fie D, Alam SA. A Study of Job Stress on Job Satisfaction among University Staff in Malaysia: Empirical Study. European Journal of Social Sciences. 2009;8:121–31. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flanagan NA, Flanagan TJ. An analysis of the relationship between job satisfaction and job stress in correctional nurses. Res Nurs Health. 2002;25:282–94. doi: 10.1002/nur.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Khatibi A, Asadi H, Hamidi M. The Relationship Between Job Stress and Organizational Commitment in National Olympic and Paralympic Academy. World Journal of Sport Sciences. 2009;2:272–8. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lambert E, Paoline EA. The Influence of Individual, Job and Organizational Characteristics on Correctional Staff Job Stress, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment. Criminal Justice Review. 2008;33:541–64. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cartledge S. Factors influencing the turnover of intensive care nurses. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2001;17:348–55. doi: 10.1054/iccn.2001.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chou-Kang C, Chi-Sheng C, Chieh-Peng L, Ching Yun H. Understanding hospital employee job stress and turnover intentions in a practical setting: The moderating role of locus of control. The Journal of Management Development. 2005;24:837–55. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuokkanen L, Leino-Kilpi H, Katajitso J. Nurse Empowerment, Job-related Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment. J Nurs Care Qual. 2003;18:184–92. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mosadeghrad AM, Moraes A. Factors affecting employees’ job satisfaction in public hospitals: Implications for recruitment and retention. Journal of General Management. 2009;34:51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 57.House R, Hanges P, Javidan M, Dorfman P, Gupta V. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The Globe Study of 62 Societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Noravesh I, Dianati Dilami Z, Bazaz MS. The impact of culture on accounting: Does Gray’s model apply to Iran?”. Review of Accounting and Finance. 2007;6:254–72. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wyatt TA. Quality of Working Life: Cross-Cultural Considerations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. 1988;6:129–40. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rahimnia F, Polychronakis Y, Sharp JM. A conceptual framework of impeders to strategy implementation from an exploratory case study in an Iranian university. Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues. 2009;2 [Google Scholar]