Abstract

Atrial fibrillation is a common arrhythmia. One of the important aspects of the management of atrial fibrillation is stroke prevention. Warfarin has been the longstanding anticoagulant used for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. There are now three novel oral anticoagulants, which have been studied in randomized controlled trials and subsequently approved by the Federal Drug Administration for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. Special patient populations, including renal insufficiency, elderly, prior stroke, and extreme body weights, were represented to varying degrees in the clinical trials of the novel oral anticoagulants. Furthermore, there is variation in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of each anticoagulant, which affect the patient populations differently. Patients and clinicians are faced with the task of selecting among the available anticoagulants, and this review is designed to be a tool for clinical decision-making.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Anticoagulation, Novel oral anticoagulants, Stroke, Warfarin

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common clinical arrhythmia, and it accounts for one-third of hospitalizations for rhythm disorders [1]. The prevalence of AF in the United States is 1 % and increases with age, such that approximately 70 % of cases of AF are in patients between 65 and 85 years of age [2]. With an aging population, the number of patients with AF is expected to increase 150 % by 2050, with more than 50 % of patients being over the age of 80 [3–8]. The increasing burden of AF is expected to lead to a higher incidence of stroke, as patients with AF have a 5- to 7-fold greater risk than the general population [9–11]. Strokes resulting from AF have a worse prognosis than in patients without AF [12, 13]. Moreover, AF is an independent risk factor for mortality with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.5 in men and 1.9 in women in the Framingham population [14]. Vitamin K antagonists (warfarin), direct thrombin inhibitors (dabigatran), and factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban and apixaban) are all oral anticoagulants that have been FDA approved for the prevention of cardioembolic events in non-valvular AF. A question on the minds of many practicing clinicians then becomes, “how should I approach the selection of an optimal agent for my patient?”. Our focused review was crafted specifically to inform and guide clinicians in daily decision-making.

Providing a foundation for drug selection based on clinical trial-derived evidence

There have been three randomized clinical trials comparing novel oral anticoagulants (NOAC) to warfarin, and a fourth trial is nearing completion (Table 1) [15–17].

Table 1.

Summary of NOAC randomized trials for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation

| RE-LY | ROCKET-AF | ARISTOTLE | ENGAGE-AF-TIMI 48 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study drug dosing | Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily | Rivaroxaban 20 mg daily | Apixaban 5 mg twice daily | Edoxaban 60 mg daily |

| Renal dosage adjustment | Dabigatran 110 mg twice daily | Rivaroxaban 15 mg daily (creatinine clearance 30–49 mL/min) | Apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily | Edoxaban 30 mg daily |

| Control group | Warfarin (INR goal 2–3) | Warfarin (INR goal 2–3) | Warfarin (INR goal 2–3) | Warfarin (INR goal 2–3) |

| Time in therapeutic range | 64.0 % | 55.0 % | 62.0 % | |

| Number of patients | 18,113 | 14,264 | 18,201 | 20,500 (estimated) |

| Trial design | Randomized, open label | Randomized, double-blind, double-dummy | Randomized, double-blind, double-dummy | |

| Average CHADS2 score | 2.2 | 3.5 | 2.1 | |

| CHADS2 score 0 or 1 | 31.9 % | 0.0 % | 34.0 % | |

| CHADS2 score 2 | 35.6 % | 13.0 % | 35.8 % | |

| CHADS2 score 3–6 | 32.5 % | 87.0 % | 30.2 % | |

| Previous stroke or TIA | 20.0 % | 54.8 % | 19.4 % | |

| Heart failure | 32.0 % | 62.5 % | 35.4 % | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 23.3 % | 40.0 % | 25.0 % | |

| Hypertension | 78.9 % | 90.5 % | 87.5 % | |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 16.6 % | 17.3 % | 14.2 % | |

| Mean age | 71 | 73 | 70 | |

| Female % | 36.4 % | 39.7 % | 35.2 % | |

| Aspirin treatment | 39.8 % | 36.5 % | 30.9 % | |

| Previous VKA use | 49.6 % | 62.4 % | 57.2 % | |

| Persistent or permanent AF | 66.8 % | 80.9 % | 84.7 % | |

| Paroxysmal AF | 33.2 % | 17.7 % | 15.3 % | |

| New AF | 0.0 % | 1.4 % | 0.0 % | |

| 25 <creatinine clearance ≤30 mL/min | 0.0 % | 0.0 % | 1.5 % | |

| 30 <creatinine clearance <50 mL/min | 19.4 % | 20.8 % | 15.2 % | |

| Creatinine clearance ≥50 mL/min | 80.6 % | 79.2 % | 83.4 % | |

| Inclusion | Non-valvular AF. 1 risk factor | Non-valvular AF. CHADS2 score ≥ 2 | Non-valvular AF. 1 risk factor | Non-valvular AF. CHADS2 score ≥ 2 |

| Definition of valvular disease | Prosthetic valve or hemodynamically relevant valve disease | Hemodynamically significant mitral valve stenosis or prosthetic valve (valve repair, commissurotomy, and valvuloplasty are permitted) | Moderate or severe mitral stenosis, mechanical valve | Moderate or severe mitral stenosis, mechanical valve |

| Follow-up | Event driven (n = 450), >12months | Event driven (n = 405), >14months | Event driven (n=448), >12months | 24 months |

| Primary end point | Composite: stroke/systemic embolism | Composite: stroke/systemic embolism | Composite: stroke/systemic embolism | Composite: stroke/systemic embolism |

| Secondary end points |

|

|

|

|

RE-LY was an open label randomized trial demonstrating that dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was superior to warfarin for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism among patients with non-valvular AF [15]. Patients taking dabigatran had lower rates of ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and intracranial bleeding (see Table 2) [15–17]. There were similar rates of major bleeding and increased rates of gastrointestinal bleeding with dabigatran at the 150 mg twice daily dose. There was a non-statistically significant signal towards a small increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) with dabigatran compared to warfarin [18]. This was also seen in a meta-analysis of 7 trials with 30,514 patients that found an increased risk of MI in those treated with dabigatran (1.2 vs. 0.8 %; OR 1.33 [1.03–1.71]) [19]. A similar trend was seen when ximelagatran was compared with warfarin for the treatment of AF [20, 21].

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for NOACs compared with warfarin

| RE-LY | ROCKET-AF | ARISTOTLE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke and systemic embolism | 0.65 (0.52–0.81) | 0.88 (0.75–1.03) | 0.79 (0.66–0.95) |

| Ischemic or unspecified stroke | 0.76 (0.60–0.98) | 0.91 (0.73–1.13) | 0.92 (0.74–1.13) |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 0.26 (0.14–0.49) | 0.59 (0.37–0.93) | 0.51 (0.35–0.75) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1.27 (0.94–1.71) | 0.81 (0.63–1.06) | 0.88 (0.66–1.17) |

| All-cause mortality | 0.88 (0.77–1.00) | 0.85 (0.70–1.02) | 0.89 (0.80–0.998) |

| Major bleeding | 0.93 (0.81–1.07) | 1.04 (0.90–1.20) | 0.69 (0.60–0.80) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 1.50 (1.19–1.89) | 1.47 (1.20–1.81) | 0.89 (0.70–1.15) |

| Intracranial bleeding | 0.40 (0.27–0.60) | 0.67 (0.47–0.93) | 0.42 (0.30–0.58) |

ROCKET AF and ARISTOTLE were randomized, double-blind, and double dummy trials that investigated rivaroxaban and apixaban, respectively, as compared with dose adjusted warfarin [16, 17]. Patients in ROCKET AF were higher risk for thromboembolic event based on CHADS2 score, as there were nearly three times as many patients with CHADS2 scores of 3–6 compared with RELY and ARISTOTLE. Rivaroxaban was non-inferior to warfarin for major bleeding and the primary endpoint of prevention of stroke or systemic embolization. Patients receiving rivaroxaban, when compared to those given warfarin, had a lower risk of hemorrhagic stroke and intracranial bleeding. There was a small, non-statistically significant trend towards decreased risk of MI with rivaroxaban.

Apixaban was superior to warfarin for the endpoint of stroke (ischemic and hemorrhagic) and major bleeding. Patients randomized to apixaban had lower rates of intracranial bleeding and a statistically significant mortality benefit compared with warfarin.

Data from ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial, comparing edoxaban and warfarin should be available in 2013 [22].

Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, metabolism, and drug–drug interactions

Dabigatran is a direct thrombin inhibitor, and apixaban and rivaroxaban are direct factor Xa inhibitors (see Table 3) [23–40]. Each agent is a reversible, active site antagonist. As summarized in Table 3, the time to peak drug levels is less than 4 h with each of the NOACs [23–25]. Apixaban and rivaroxaban are both nearly 90 % protein bound, while dabigatran is 30 % protein bound [26–28]. The proportion of renal excretion for apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban vary and are 27, 80, and 36 %, respectively [23, 24, 29]. Food can slightly alter the absorption of these medications, as taking the medication with food will prolong absorption of dabigatran and increase factor Xa inhibition with rivaroxaban [30, 31]. Dabigatran bioavailability is decreased by approximately 20 % with concomitant proton pump inhibitor use; however, the clinical impact of this reduction was not evident in RE-LY [32]. Apixaban and rivaroxaban both have potential drug–drug interactions with medications affecting the CYP3A4 pathway of metabolism/clearance and, to a lesser degree, P-gp pathways. Patients taking these medications (ketoconazole, clarithromycin, erythromycin, rifampin, and protease inhibitors) were excluded from the clinical trials [26, 33]. Dabigatran is also a substrate for P-gp and, accordingly, clinicians must be aware of concomitant medications that may either increase or decrease reverse transport (and plasma drug levels) when prescribing.

Table 3.

Summary of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of available NOACs

| Apixaban | Dabigatran | Rivaroxaban | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of action | Direct factor Xa inhibitor | Direct thrombin inhibitor | Direct factor Xa inhibitor |

| Bioavailability | 50 % [40] | 6–7 % [37] | 66 % [26] |

| Time to peak levels | 1 h [23] | 1.5 h [24] | 3–4 h [25] |

| Half-life | 12.7 h [ 23] | 7–9 h after 1 dose, 14–17 h after multiple doses [24] | 6–9 h after multiple doses [25] |

| Protein binding | 87 % [27] | 30 % [28] | 92–95 % [26] |

| Hepatic metabolism | 50 % [26] | ||

| Clearance | |||

| Renal | 25–29 % [23] | 80 % [24] | 36 % [29] |

| Fecal | 47–56 % [23] | 28 % [29] | |

| Biliary | 1–2 % [23] | ||

| Effect of food | No effect on exposure [27] | Delays absorption: time to peak levels 4 [30] | Peak levels at 3 h fasting and 4 h with food. Factor Xa inhibition increased with food [31] |

| Effect of age | Exposure is 32 % higher in patients >65 years old [27] | Bioavailability 1.7–2 times greater in elderly [32] | Bioavailability is greater in elderly with half life 11–13 h with no difference in peak concentration [35] |

| Effect of body weight | Weight <50 kg had 20–30 % higher exposure and weight >120 kg had 20–30 % lower exposure [27] | None [30] | None with weight >120 kg. Peak concentration 24 % higher and half- life 10 h in patients <50 kg [ 36] |

| Effect of renal impairment | No effect on peak concentration. Increase in exposure of 16, 29, and 44 % for creatinine clearance of 51–80, 30–50, and 15–29 mL/min, respectively [27] | Severe impairment: sixfold higher exposure with half- life of 28 h [ 34] | Similar increase in exposure with moderate (creatinine clearance 30–49 mL/min or severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance 15–29 mL/min) [26] |

| Effect hepatic impairment | No change in exposure with Child-Pugh classification A or B [27] | None with Child-Pugh classification B [38] | Significant increase in exposure with Child-Pugh classification B. Not recommended for Child-Pugh classification B or C [26] |

| Medication interactions | Interaction with medications affecting both CYP3A4 and P-gp pathways (clarithromycin, erythromycin, ketoconazole, rifampin, and protease inhibitors) [33] | Decrease in bioavailability by 20–24% with pantoprazole [ 32 ] | No changes in activity with ranitidine or

antacid [9] Interaction with medications affecting both CYP3A4 and P-gp pathways (clarithromycin, erythromycin, ketoconazole, rifampin, and protease inhibitors) [ 26 ] |

| Impact on QTc Interval | None [39] | ||

| Other | Hemodialysis removes 62–68 % [34] | ||

References are listed in square brackets

Specific patient populations

Creatinine clearance/renal function

Apixaban and rivaroxaban have renal clearance of 27 and 36 %, respectively [23, 29]. Dabigatran has renal clearance of 80 %, and patients have sixfold higher exposure to the drug with severe renal impairment [24, 34].

Patients were excluded from RE-LY and ROCKET AF if they had a creatinine clearance of <30 mL/min. The doses of dabigatran studied in RE-LY were 150 and 110 mg twice daily with no dose adjustment based on creatinine clearance [15]. The FDA approved a dose of 75 mg twice daily for patients with creatinine clearance between 15 and 30 mL/min, based on pharmacokinetic modeling [41, 42]. Clinical data are not available for the 75 mg twice daily dose. ROCKET AF studied rivaroxaban 20 mg daily in patients with normal and mild renal impairment with creatinine clearance ≥50 mL/min and 15 mg daily for patients with moderate renal impairment and creatinine clearance between 30 and 49 mL/min [16].

A subgroup analysis of patients with moderate renal impairment, creatinine clearances between 30 and 49 mL/min, in ROCKET AF compared 1474 patients receiving rivaroxaban 15 mg with 1476 dose adjusted warfarin patients. Rivaroxaban in patients with moderate renal insufficiency showed non-inferiority to warfarin for the primary safety endpoint, which mirrored the overall trial results. Moderate renal impairment patients had decreased fatal bleeding relative to warfarin, as seen in the cohort with normal to mild renal insufficiency, and similar levels of intracranial hemorrhage, which differed from the lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage in rivaroxaban patients with creatinine clearance ≥50 mL/min [43]. The dosing recommendations of rivaroxaban are for the 15 mg daily dose for patients with creatinine clearance of 15–49 mL/min.

ARISTOTLE excluded patients with a creatinine clearance of<25 mL/min or a creatinine of greater than 2.5 mg/ dL. Patients received the standard 5 mg twice daily dose or were reduced to 2.5 mg twice daily if they had two of the following criteria: age >80, creatinine >1.5 mg/dL, and weight <60 kg [17]. A subgroup analysis from ARISTOTLE compared 7518 patients with normal renal function, 7587 patients with mild renal impairment, and 3017 patients with moderate renal impairment, as defined by estimated glomerular filtration rates of >80 mL/min, between 50 and 80 mL/min, and <50 mL/min, respectively. The hazard ratios for stroke and systemic embolism, as well as, all-cause mortality favored apixaban over warfarin across all three patient cohorts. Patients with moderate renal impairment had the greatest reduction in risk of bleeding among patients taking apixaban compared with warfarin [44].

Patients with renal impairment have higher incidence of bleeding with anticoagulation. These patients also have higher bioavailability of the NOACs, especially dabigatran, which has the highest rate of renal clearance. Apixaban and rivaroxaban may, therefore, be more attractive agents for patients with renal impairment, as these medications have demonstrated a reduction in risk of bleeding compared with warfarin in this patient population. Warfarin should still be used for patients with severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <25 mL/min).

Valvular disease

There are no clinical trial data comparing warfarin and NOACs in patients with valvular heart disease or mechanical valves, as these patients were not enrolled in RE-LY, ROCKET AF, and ARISTOTLE based on the entry and exclusion criteria. The AVERROES trial was a double-blinded study comparing apixaban to aspirin in patients with AF, who were not candidates for warfarin therapy. The study was terminated early because the apixaban was found to be superior to aspirin with respect to reduction of stroke and systemic embolism (HR 0.45; CI 0.32–0.62, p <0.001) with no significant increased risk in major bleeding or intracranial hemorrhage [45]. Approximately 2 % of the patients in the trial had mitral stenosis, but given the small numbers, no subgroup analysis on these patients has been done.

An animal study demonstrated effectiveness of dabigatran compared with enoxaparin for mechanical aortic valves [46], and an in vitro study with human blood showed effectiveness of high dose rivaroxaban compared with unfractionated heparin and low molecular weight heparin for mechanical aortic valves [47]. RE-ALIGN was an open label, randomized, blinded end-point phase II trial that evaluated the safety of dabigatran compared with warfarin in patients with aortic and mitral, mechanical bi-leaflet valves. The trial was designed to include patients between 18 and 75 years old to be randomized either during the valve implant hospitalization or greater than 3 months after receiving a mechanical valve. Both arms of the trial were terminated prematurely due to increased thromboembolic and bleeding events in the dabigatran arm. The immediate post-surgery arm was stopped first due to safety concerns of low plasma levels of dabigatran and higher thromboembolic events in the dabigatran patients. The 3 month post-surgery arm randomized patients to initial dabigatran doses of 150, 220, or 300 mg twice daily based on creatinine clearance of <70 mL/min, between 70 and 110 mL/min, and>110 mL/min, respectively. Patients had dabigatran plasma levels checked and had doses titrated up to a maximum of 300 mg twice daily if dabig-atran plasma levels are <50 ng/mL, and patients with levels <50 ng/mL on dabigatran 300 mg twice daily will be changed to warfarin [48].

There have been case reports of patients with mechanical valves developing thrombus on the valves shortly after being changed from warfarin to dabigatran [49]. Until more data becomes available, warfarin is the safest option for patients with valvular disease.

Elderly patients

Elderly patients with AF are the patients that benefit the most from antithrombotic therapy [50], but they have been undertreated, historically. Based on data from approximately 11,000 patients in the ATRIA cohort, who had no contraindications to warfarin, only 35 % of patients >85 years old were treated with oral anticoagulation compared with 62 % of patients between 65 and 74 years old [51]. Physicians state that concern for falls and hemorrhage, respectively, are the most common reasons to refrain from oral anticoagulation in elderly with AF [52]. Data from patients on warfarin in ATRIA identified 90 % of bleeding related deaths were due to intracranial hemorrhage [53]. Bleeding rates on warfarin are particularly high when elderly patients have supratherapeutic INRs, as 25 % of major hemorrhages are associated with supratherapeutic anticoagulation [54]. The NOACs have the potential to reduce the time that patients spend outside of the therapeutic window, and the lower rates of intracranial hemorrhage for NOACs as compared with warfarin may be particularly important for elderly patients. Bioavailability in the elderly is higher than in the non-elderly with all NOACs, although apixaban has the lowest increase in exposure and dabigatran has the highest with a 70–100 % increase [27, 32, 35].

It is reasonable to apply the results of NOAC trials to patients >75 years old, as these patients were well represented in the trials. The median ages of patients in ARIS-TOTLE, RE-LY, and ROCKET AF were 70, 71.5, and 73 years old, respectively. Patients >76 years old were 25 % of the patients in ARISTOTLE, and patients > 78 years old were 25 % of the patients in ROCKET AF.

Elderly patients have a higher incidence of polypharmacy and renal impairment secondary to decreased creatinine clearance with age. The NOACs may provide a more attractive drug interaction profile with less impact on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics for most patients with polypharmacy, as compared with warfarin. As previously described, mild or moderate renal impairment is not a limitation with NOACs, but severe renal impairment is currently a limiting factor. Dosing frequency is also a major consideration in the elderly. A study of 690 patients >64 years old found that medications taken more than once daily had a significant increase in non-adherence (OR 2.99, 95 % CI 1.24–7.17) [55]. These findings may make once daily drugs such as rivaroxaban and warfarin more attractive options than twice daily drugs such as apixaban and dabigatran; however, any of the NOACs are reasonable to consider for patients >75 years old.

Body weight <60 kg or >120 kg

There have been no observed variations in bioavailability or peak concentrations with dabigatran in patients that are obese or underweight [30]. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics with factor Xa inhibitors are affected by weight, but there is no available data on the clinical impact of these effects. ARISTOTLE had weight<60 kg as one of two needed criteria for a dose reduction to 2.5 mg twice daily. Patients with weight <50 and >120 kg have a 20–30 % higher and 20–30 % lower exposure, respectively to apixaban [27]. There were not dose adjustments in ROCKET AF based on weight, but there is a 24 % increase in peak concentration and slight increase in half-life to 10 h in patients < 50 kg. There has been no effect noted in patients weighing >120 kg [36]. The challenge with medical decision-making for patients with very low or very high body weight is that these patients make up a small proportion of the patients in the trials. Due to the limited data in these patients, it may be safest to use warfarin until more data is available.

Hepatic impairment

Patients with active liver disease such as acute hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis, and cirrhosis were excluded from RE-LY, ROCKET AF, and ARISTOTLE [15–17]. Patients were also excluded from the trials if there was evidence of hepatic impairment on baseline laboratory values. RE-LY excluded patients with ALT, AST, or alkaline phosphatase greater than twice the upper limit of normal [15]. ROCKET AF excluded patients with ALT greater than three times the upper limit of normal [16]. ARISTOTLE excluded patients with ALT or AST greater than twice the upper limit of normal or a total bilirubin greater than one and a half times the upper limit of normal [17]. Patients with Child-Pugh classification of A or B did not have a significant change in exposure to apixaban or dabigatran [27, 38]. Patients with Child-Pugh classification B taking rivaroxaban did experience a greater than twofold increase in exposure, and the medication is not recommended for patients with Child-Pugh classification B or C [26]. Based on the conservative exclusion criteria for the clinical trials, it may be best to use warfarin for patients with hepatic impairment, meaning active liver disease or liver function tests greater than twice the upper limit of normal.

Prior stroke or TIA

There has been a substudy in each of the NOAC trials investigating differences in events based on presence or absence of previous stroke or TIA. ARISTOTLE and ROCKET AF had 3436 and 7468 patients, respectively with previous stroke or TIA [56, 57]. RE-LY had 2428 patients in the warfarin and dabigatran 150 mg cohorts with previous stroke or TIA [58]. All of the substudies found that patients with previous stroke or TIA were at higher risk of major bleeding, stroke, or systemic embolism compared with patients without a previous stroke of TIA. This was true regardless of anticoagulation strategy for the patients, meaning that there was no difference between the effects of the NOACs and warfarin when comparing rates of 1) stroke or systemic embolism or 2) major hemorrhage in patients with and without a history of stroke or TIA. Patients with previous stroke or TIA were more likely to have a hemorrhagic stroke than their counterparts, and each of the NOACs had a statistically lower incidence of hemorrhagic stroke in patients with a history of previous stroke or TIA compared with warfarin. All three of the NOACs should be considered for patients with previous stroke or TIA.

Triple therapy

Several studies have investigated NOAC in the treatment of patients with ACS (regardless of AF status). Using the same dose of apixaban as the ARISTOTLE trial, APPRAISE-2 evaluated apixaban in addition to antiplatelet therapy: aspirin (16 % of patients) or aspirin and clopidogrel (81 % of patients) for the prevention of recurrent ischemic events. In APPRAISE-2 apixaban increased major bleeding (HR 2.59 [1.50–4.46]), including more frequent fatal and intracranial bleeding events with no clinical benefit [59]. ATLAS ACS 2-TIMI 51 evaluated the use of rivaroxaban with antiplatelet therapy (99 % on aspirin and 93 % on clopidogrel). The doses of rivaroxaban used in ATLAS ACS 2 were much smaller than those in ROCKET AF (2.5 and 5 mg twice daily vs. 20 mg daily). Those randomized to low-dose rivaroxaban had a 16 % reduction in the composite efficacy endpoint (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke). There were increased rates of major bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage among the rivaroxaban patients, but there was no change in fatal bleeding [60]. Neither of these ACS trials was designed to investigate the impact of triple therapy on stroke or survival for AF patients after ACS and/or PCI.

The 2011 ACC/AHA guideline update and a position paper by European Society of Cardiology cite the lack of data and uncertainty regarding combination therapy in patients with AF who undergo PCI [61, 62]. No secondary analysis from the NOAC trials has been released describing the experiences of patients on a NOAC, who then had dual antiplatelet therapy added after PCI. The WOEST trial was designed as a randomized trial comparing dual therapy (oral anticoagulation and clopidogrel) and triple therapy (oral anticoagulation, clopidogrel, and aspirin) after PCI [63]. The results of WOEST were presented at the 2012 European Society of Cardiology. The 573 patient trial found significantly less bleeding events (p <0.001) with no statistically significant decrease in major bleeding (p = 0.159) among patients on dual therapy. The composite efficacy (death, MI, target vessel revascularization, stroke, and stent thrombosis) favored dual therapy to triple therapy (HR 0.60, CI 0.38–0.94, p = 0.025), although the trial was not powered to analyze efficacy [64]. Additional randomized trials evaluating combination oral anticoagulation, especially NOAC, and antiplatelet therapy after PCI and ACS are needed. The ISAR-TRIPLE is a randomized trial comparing triple therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and vitamin K antagonist for 6 weeks versus 6 months after placement of a drug eluting stent. After triple therapy the patients take aspirin and vitamin K antagonist. Results from this trial are expected in late 2014. The MUSICA-2 trial is also an ongoing randomized trial that is comparing triple therapy with acetylsalicylic acid 100 mg daily, clopidogrel 75 mg daily, and dose adjusted acenocoumarol and dual therapy with acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel. This trial is expected to close in December 2012.

Given the increased risk of intracranial hemorrhage in APPRAISE-2, until more data are available, the most conservative approach will be to restrict triple therapy to the use of warfarin. It is also important to limit the duration of triple therapy by using bare metal stents unless there is a significant benefit to drug eluting stents (class IIa recommendation) [65]. There may be increased complexity of decision-making in the future, if the NOACs are approved for ACS at different doses than have been approved for AF stroke prevention.

Risk scores for risk of stroke (CHADS2 and CHADS2-Vasc) and risk of bleeding (HAS-BLED) on oral anticoagulation can also be utilized in decision-making. The European Society of Cardiology has different antiplatelet and anticoagulation recommendations for AF patients at low risk of bleeding (HAS-BLED score of 0–2) compared with patients at high risk of bleeding (HAS-BLED ≥ 3) [66]. Similarly Paikin et al. proposed that anticoagulated patients who receive a stent should be placed on dual or triple therapy based on a combination of risk scores for thromboembolism and bleeding. Patients with CHADS2 scores of 0–1 or patients with CHADS2 scores>1 but at high risk of bleeding should receive dual antiplatelet therapy. Patients with CHADS2 scores >1 and at low risk of bleeding should receive triple therapy [67]. Patient values and preferences for accepting risk of bleeding versus risk of thromboembolism need to play a large role in decision-making.

Comparison of oral anticoagulants

There are over 50,000 patients in ARISTOTLE, RE-LY, and ROCKET AF. There have been three meta-analyses reported with the cumulative class of NOACs compared with warfarin. The findings of the three studies are similar (see Table 4) [68–70]. The NOACs have significantly fewer events of stroke and systemic embolism, hemorrhagic stroke, and intracranial bleeding. The meta-analyses demonstrate an all-cause mortality benefit for the NOACs, similar to that seen in ARISTOTLE. There is no statistically significant difference in major bleeding (with the exception of Lip et al.) or gastrointestinal bleeding, as compared with warfarin. This data supports the use of NOACs in place of warfarin unless there are special patient populations, such as triple therapy.

Table 4.

Comparison of events of cumulative NOAC patients to warfarin

| Miller et al. 2012 | Lip et al. 2012 | Baker et al. 2012a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stroke and systemic embolism | RR 0.78 (0.67–0.92) | HR 0.793 (0.714–0.881) | RR 0.797 (0.695–0.914) |

| Stroke | N/A | HR 0.769 (0.684–0.864) | RR 0.765 (0.640–0.915) |

| Ischemic and unspecified stroke | RR 0.87 (0.77–0.99) | HR 0.878 (0.771–1.000) | RR 0.880 (0.742–1.044) |

| All cause mortality | N/A | HR 0.880 (0.815–0.950) | RR 0.874 (0.803–0.974) |

| Myocardial infarction | N/A | HR 0.949 (0.807–1.116) | N/A |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | RR 0.45 (0.32–0.68) | HR 0.474 (0.363–0.619) | RR 0.455 (0.269–0.768) |

| Major bleeding | RR 0.88 (0.71–1.09) | HR 0.875 (0.806–0.950) | RR 0.878 (0.664–1.160) |

| Intracranial bleeding | RR 0.49 (0.36–0.66) | HR 0.490 (0.400–0.601) | N/A |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | RR 1.25 (0.91–1.72) | N/A | RR 1.254 (0.827–1.901) |

Includes data from PETRO in stroke and systemic embolism, major bleeding

Similarly, there are five published works based on indirect comparisons of apixaban, dabigatran 150 mg, and rivaroxaban. There are limitations in this methodology, as the indirect comparison methodology introduces multiple confounders. Furthermore, the patient populations are different between the trials, and this is most significant for the higher risk of stroke and systemic embolism (higher CHADS2 score) in ROCKET AF. Despite variations in methodology, each indirect comparison manuscript arrived at similar results (see Table 5) [68, 70–73]. Dabigatran 150 mg was found to have a statistically significant fewer number of strokes and systemic embolism, as well as, hemorrhagic strokes compared with rivaroxaban. Apixaban had a lower rate of major bleeding and gastrointestinal bleeding compared to dabigatran 150 mg or rivaroxaban. Schneeweiss et al. specifically compared the NOACs among high risk patients (CHADS2 ≥ 3) and found that apixaban had lower major bleeding than rivaroxaban, but the agents were otherwise undifferentiated in this patient population. Neither these nor future indirect comparisons are a substitute for a “head-to-head” randomized trial, but they do provide general direction because of a required understanding of the patients represented in individual clinical trials.

Table 5.

Indirect comparison between NOACs and a sub-group, indirect analysis of high CHADS2 patients

| Lip et al. 2012 | Mantha et al. 2012 | Baker et al. 2012 | Schneeweiss et al. 2012 | Harenberg et al. 2012 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Apixaban vs. dabigatran |

Dabigatran vs. rivaroxaban |

Apxiaban vs. rivaroxaban |

Apixaban vs. dabigatran |

Rivaroxaban vs. dabigatran |

Apxiaban vs. rivaroxaban |

Apixaban vs. dabigatran |

Dabigatran vs. rivaroxaban |

Apxiaban vs. Rivaroxaban |

Dabigatran vs. apixaban |

Dabigatran vs. rivaroxaban |

Apxiaban vs. rivaroxaban |

Dabigatran vs. apixaban |

Dabigatran vs. rivaroxaban |

Rivaroxaban vs. apixaban |

|

| Stroke and systemic embolism | HR 1.22 (0.91–1.62) |

HR 0.74 (0.56–0.97) |

HR 0.90 (0.71–1.13) |

OR 1.22 (0.91–1.62) |

OR 1.35 (1.02–1.78) |

OR 0.90 (0.71–1.16) |

RR 1.193 (0.902–1.579) |

RR 0.758 (0.580–0.992) |

RR 0.905 (0.712–1.150) |

HR 0.82 (0.62–1.10) |

N/A | N/A | RR 0.82 (0.61–1.10) |

RR 0.74 (0.56–0.98) |

RR 1.11 (0.86–1.42) |

| Stroke | HR 1.23 (0.92–1.66) |

HR 0.75 (0.56–1.02) |

HR 0.93 (0.71–1.22) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | RR 1.213 (0.907–1.622) |

RR 0.783 (0.582–1.053) |

RR 0.949 (0.727–1.238) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ischemic and unspecified stroke | HR 1.21 (0.88–1.67) |

HR 0.81 (0.58–1.13) |

HR 0.98 (0.72–1.33) |

OR 1.20 (0.86–1.67) |

OR 1.19 (0.85–1.65) |

OR 1.02 (0.75–1.38) |

RR 1.190 (0.860–1.645) |

RR 0.676 (0.490–0.933) |

RR 0.804 (0.598–1.082) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| All cause mortality | HR 1.01 (0.85–1.20) |

HR 1.04 (0.82–1.30) |

HR 1.05 (0.84–1.30) |

OR 1.01 (0.85–1.20) |

OR 1.04 (0.87–1.24) |

OR 0.97 (0.83–1.15) |

RR 1.007 (0.855–1.185) |

RR 1.069 (0.859–1.331) |

RR 1.077 (0.873–1.328) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | RR 0.99 (0.83–1.18) |

RR 0.96 (0.81–1.15) |

RR 0.91 (0.73–1.13) |

| Myocardial infarction | HR 0.69 (0.46–1.05) |

HR 1.57 (1.05–2.33) |

HR 1.09 (0.74–1.60) |

OR 0.68 (0.45–1.03) |

OR 0.62 (0.42–0.93) |

OR 1.10 (0.74–1.62) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | RR 1.00 (0.97–2.23) |

RR 1.61 (1.08–2.41) |

RR 0.91 (0.62–1.34) |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | HR 1.96 (0.94–4.08) |

HR 0.44 (0.20–0.96) |

HR 0.86 (0.48–1.57) |

OR 1.93 (0.92–4.07) |

OR 2.20 (1.00–4.84) |

OR 0.88 (0.48–1.59) |

RR 1.933 (0.929–-4.017) |

RR 0.454 (0.210–0.983) |

RR 0.878 (0.487–1.583) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Major bleeding | HR 0.74 (0.61–0.91) |

HR 0.89 (0.73–1.09) |

HR 0.66 (0.54–0.81) |

OR 0.74 (0.61–0.91) |

OR 1.10 (0.90–1.34) |

OR 0.68 (0.55–0.83) |

RR 0.753 (0.619–0.916) |

RR 0.913 (0.753–1.107) |

RR 0.688 (0.566–0.835) |

HR 1.42 (1.16–1.74) |

N/A | N/A | RR 1.35 (1.10–1.66) |

RR 0.92 (0.75–1.12) |

RR 1.48 (1.21–1.81) |

| Intracranial bleeding | HR 1.05 (0.63–1.76) |

HR 0.60 (0.35–1.01) |

HR 0.63 (0.39–1.01) |

OR 1.02 (0.62–1.68) |

OR 1.58 (0.94–2.63) |

OR 0.64 ( 0.40–1.03) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | RR 1.00 (0.60–1.67) |

RR 0.65 (0.30–1.09) |

RR 1.55 (0.96–2.50) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | HR 0.59 (0.42–0.83) |

N/A | N/A | OR 0.59 (0.41–0.83) |

OR 0.99 (0.72–1.34) |

OR 0.60 (0.43–0.83) |

RR 0.603 (0.434–0.838) |

RR 0.970 (0.715–1.314) |

RR 0.585 (0.414–0.826) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Patients with CHADS2 ≥ 3 | |||||||||||||||

| Stroke and systemic embolism | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | HR 1.03 (0.69–1.54) |

HR 0.80 (0.56–1.13) |

HR 0.77 (0.56–1.06) |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Major bleeding | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | HR 1.52 (1.11–2.07) |

HR 1.04 (0.80–1.34) |

HR 0.68 (0.52–0.90) |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

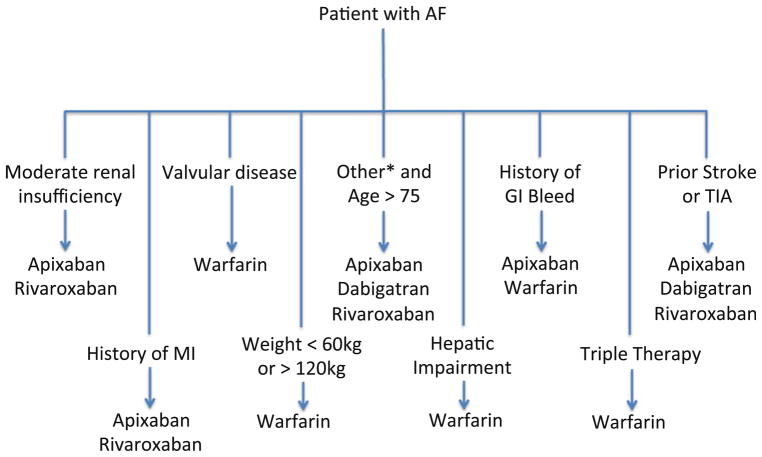

We have utilized all of the data available to develop an algorithm for selecting an anticoagulant. The focus of the algorithm is on customization based on patient characteristics (see Fig. 1). In patients with renal insufficiency, one should consider apixaban or rivaroxaban, given that these agents have a lower percentage of renal clearance and a more muted effect on exposure with change in creatinine clearance. When selecting a NOAC for an elderly patient, it is important to consider that these patients are at high risk of acute kidney injury; however, it is reasonable to consider apixaban, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban for these elderly patients. For patients with history of MI, there remains a question of a signal in the direction of increased MI with dabigatran, so apixaban and rivaroxaban may be better as first line agents. Warfarin should be used with valvular disease/mechanical valves, severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <25 mL/min), extreme low or extreme high weights, and triple therapy until additional data is available. ROCKET AF found rivaroxaban to be non-inferior to warfarin in the highest risk patients of the NOAC trials, so it has the best data for use in previous stroke or TIA, but it is also reasonable to consider apixaban and dabigatran for these patients. Apixaban is the only agent with a proven mortality benefit compared with warfarin in a randomized, double-blinded study, but dabigatran and rivaroxaban should also be considered for patients with no other comorbidities.

Fig. 1.

Algorithm for selecting an oral anticoagulant

This review is designed to provide guidance for clinical decision-making. Ultimately, there is significant variation among patients concerning values and patient preferences, and these factors will need to be assessed and considered on a case-by-case basis for decision-making [74]. The pharmacoeconomics of NOACs is outside the scope of this review, but cost and insurance coverage are often an important influence on decision-making. Patient preferences, especially those based on prior personal experience with warfarin, may also impact decision-making.

Conclusion

The options for oral anticoagulation for patients with AF have expanded, and the NOACs are good alternatives to warfarin. As a class, the NOACs are effective and safe when compared with warfarin. Each agent has strengths and weaknesses that allow for customization based on a given patient situation. As additional outcomes data become available, the selection algorithm will continue to change and be refined. Ultimately, patient values, preferences, and cost are key factors that need to be incorporated into the decision-making process.

Contributor Information

Sean D. Pokorney, Email: sean.pokorney@dm.duke.edu, sean.pokorney@duke.edu, Division of Cardiology, Duke University Medical Center, Duke University Hospital, 2301 Erwin Rd, DUMC 3845, Durham, NC 27710, USA. Duke Clinical Research Institute, P. O. Box 17969, Durham, NC 27715, USA

Matthew W. Sherwood, Division of Cardiology, Duke University Medical Center, Duke University Hospital, 2301 Erwin Rd, DUMC 3845, Durham, NC 27710, USA. Duke Clinical Research Institute, P. O. Box 17969, Durham, NC 27715, USA

Richard C. Becker, Division of Cardiology, Duke University Medical Center, Duke University Hospital, 2301 Erwin Rd, DUMC 3845, Durham, NC 27710, USA. Duke Clinical Research Institute, P. O. Box 17969, Durham, NC 27715, USA. Division of Hematology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA

References

- 1.Wann LS, Curtis AB, January CT, Ellenbogen KA, Lowe JE, Estes NA, III, Page RL, Ezekowitz MD, Slotwiner DJ, Jackman WM, Stevenson WG, Tracy CM, Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Le Heuzey JY, Crijns HJ, Lowe JE, Curtis AB, Olsson SB, Ellenbogen KA, Prystowsky EN, Halperin JL, Tamargo JL, Kay GN, Wann LS, Jacobs AK, Anderson JL, Albert N, Hochman JS, Buller CE, Kushner FG, Creager MA, Ohman EM, Ettinger SM, Stevenson WG, Guyton RA, Tarkington LG, Halperin JL, Yancy CW. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (Updating the 2006 Guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(2):223–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feinberg WM, Blackshear JL, Laupacis A, Kronmal R, Hart RG. Prevalence, age distribution, and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation: analysis and implications. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(5):469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novaro GM, Asher CR, Bhatt DL, Moliterno DJ, Harrington RA, Lincoff AM, Newby LK, Tcheng JE, Hsu AP, Pinski SL. Meta-analysis comparing reported frequency of atrial fibrillation after acute coronary syndromes in Asians versus whites. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(4):506–509. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.09.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang YC, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults. JAMA. 2001;285(18):2370–2375. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Manolio TA. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in elderly subjects (the cardiovascular health study) Am J Cardiol. 1994;74(3):236–241. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Psaty BM, Manolio TA, Kuller LH, Kronmal RA, Cushman M, Fried LP, White R, Furberg CD, Rautaharju PM. Incidence of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation in older adults. Circulation. 1997;96(7):2455–2461. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Cha SS, Bailey KR, Abhayaratna WP, Seward JB, Tsang TS. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence. Circulation. 2006;114(2):119–125. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D’Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. JAMA. 1994;271(11):840–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation: a major contributor to stroke in the elderly: the Framingham study. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147(9):1561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf PA, Dawber TR, Thomas HE, Jr, Kannel WB. Epidemiologic assessment of chronic atrial fibrillation and risk of stroke. Neurology. 1978;28(10):973–978. doi: 10.1212/wnl.28.10.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flegel K, Shipley M, Rose G. Risk of stroke in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation. Lancet. 1987;329(8532):526–529. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin HJ, Wolf PA, Kelly-Hayes M, Beiser AS, Kase CS, Benjamin EJ, D’Agostino RB. Stroke severity in atrial fibrillation: the Framingham study. Stroke. 1996;27(10):1760–1764. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, Cha SS, Gersh BJ, Seward JB, Tsang TS. Mortality trends in patients diagnosed with first atrial fibrillation: a 21-year community-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(9):986–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 1998;98(10):946–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, Pogue J, Reilly PA, Themeles E, Varrone J. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, Breithardt G, Halperin JL, Hankey GJ, Piccini JP. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–891. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, Lopes RD, Hylek EM, Hanna M, Al-Khalidi HR, Ansell J, Atar D, Avezum A. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):981–992. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hohnloser SH, Oldgren J, Yang S, Wallentin L, Ezekowitz M, Reilly P, Eikelboom J, Brueckmann M, Yusuf S, Connolly SJ. Myocardial ischemic events in patients with atrial fibrillation treated with dabigatran or warfarin in the RE-LY (Randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulation therapy) trial. Circulation. 2012;125(5):669–676. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uchino K, Hernandez AV. Dabigatran association with higher risk of acute coronary events: meta-analysis of noninferiority randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):397–402. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsson SB. Stroke prevention with the oral direct thrombin inhibitor ximelagatran compared with warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (SPORTIF III): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362(9397):1691–1698. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flaker GC, Gruber M, Connolly SJ, Goldman S, Chaparro S, Vahanian A, Halinen MO, Horrow J, Halperin JL. Risks and benefits of combining aspirin with anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: an exploratory analysis of stroke prevention using an oral thrombin inhibitor in atrial fibrillation (SPORTIF) trials. Am Heart J. 2006;152(5):967–973. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Antman EM, Crugnale SE, Bocanegra T, Mercuri M, Hanyok J, Patel I, Shi M, Salazar D, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. Evaluation of the novel factor Xa inhibitor edoxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: design and rationale for the effective aNticoaGulation with factor xA next generation in atrial fibrillation-thrombolysis in myocardial infarction study 48 (ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48) Am Heart J. 2010;160(4):635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raghavan N, Frost CE, Yu Z, He K, Zhang H, Humphreys WG, Pinto D, Chen S, Bonacorsi S, Wong PC, Zhang D. Apixaban metabolism and pharmacokinetics after oral administration to humans. Drug metab dispos: biol fate chem. 2009;37(1):74–81. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.023143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stahle H, Gansser D, Roth W. The pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and tolerability of dabigatran etexilate, a new oral direct thrombin inhibitor, in healthy male subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64(3):292–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kubitza D, Becka M, Wensing G, Voith B, Zuehlsdorf M. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of BAY 59–7939–an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor–after multiple dosing in healthy male subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;61(12):873–880. doi: 10.1007/s00228-005-0043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FDA. Drug: XARELTO (rivaroxaban) Tablets. indication for use: prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. FDA; 2011. Briefing document for the cardiovascular and renal drugs advisory committee (CRDAC) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Product monograph PrELIQUIS (apixaban) (2011)

- 28.Advisory Committee Briefing Document. Pradaxa (dabigatran etexilate) (2010)

- 29.Weinz C, Schwarz T, Kubitza D, Mueck W, Lang D. Metabolism and excretion of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor, in rats, dogs, and humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37(5):1056–1064. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.025569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stangier J. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47(5):285–295. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kubitza D, Becka M, Zuehlsdorf M, Mueck W. Effect of food, an antacid, and the H2 antagonist ranitidine on the absorption of BAY 59–7939 (rivaroxaban), an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor, in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46(5):549–558. doi: 10.1177/0091270006286904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stangier J, Stahle H, Rathgen K, Fuhr R. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the direct oral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran in healthy elderly subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47(1):47–59. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L, Zhang D, Raghavan N, Yao M, Ma L, Frost CE, Maxwell BD, Chen SY, He K, Goosen TC, Humphreys WG, Grossman SJ. In vitro assessment of metabolic drug–drug interaction potential of apixaban through cytochrome P450 phenotyping, inhibition, and induction studies. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38(3):448–458. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.029694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stangier J, Rathgen K, Stahle H, Mazur D. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open-label, parallel-group, single-centre study. Clinical Pharmacokinet. 2010;49(4):259–268. doi: 10.2165/11318170-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kubitza D, Becka M, Mueck W, Zuehlsdorf M. The effect of extreme age, and gender, on the pharmacology and tolerability of rivaroxaban–an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor. Blood. 2006;108:A905. doi: 10.1177/0091270006292127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kubitza D, Becka M, Zuehlsdorf M, Mueck W. Body weight has limited influence on the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, or pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban (BAY 59–7939) in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47(2):218–226. doi: 10.1177/0091270006296058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blech S, Ebner T, Ludwig-Schwellinger E, Stangier J, Roth W. The metabolism and disposition of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran, in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(2):386–399. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.019083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stangier J, Stahle H, Rathgen K, Roth W, Shakeri-Nejad K. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dabigatran etexilate, an oral direct thrombin inhibitor, are not affected by moderate hepatic impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48(12):1411–1419. doi: 10.1177/0091270008324179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kubitza D, Mueck W, Becka M. Randomized, double-blind, crossover study to investigate the effect of rivaroxaban on QT-interval prolongation. Drug Saf. 2008;31(1):67–77. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200831010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He K, Luettgen JM, Zhang D, He B, Grace JE, Jr, Xin B, Pinto DJ, Wong PC, Knabb RM, Lam PY, Wexler RR, Grossman SJ. Preclinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of apixaban, a potent and selective factor Xa inhibitor. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2011;36(3):129–139. doi: 10.1007/s13318-011-0037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hariharan S, Madabushi R. Clinical pharmacology basis of deriving dosing recommendations for dabigatran in patients with severe renal impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(1 Suppl):119S–125S. doi: 10.1177/0091270011415527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lehr T, Haertter S, Liesenfeld KH, Staab A, Clemens A, Reilly PA, Friedman J. Dabigatran etexilate in atrial fibrillation patients with severe renal impairment: dose identification using pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(9):1373–1378. doi: 10.1177/0091270011417716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fox KA, Piccini JP, Wojdyla D, Becker RC, Halperin JL, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Hankey GJ, Mahaffey KW, Patel MR, Singer DE, Califf RM. Prevention of stroke and systemic embolism with rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and moderate renal impairment. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(19):2387–2394. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hohnloser SH, Hijazi Z, Thomas L, Alexander JH, Amerena J, Hanna M, Keltai M, Lanas F, Lopes RD, Lopez-Sendon J, Granger CB, Wallentin L. Efficacy of apixaban when compared with warfarin in relation to renal function in patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. Eur Heart J. 2012 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C, Diener HC, Hart R, Golitsyn S, Flaker G, Avezum A, Hohnloser SH, Diaz R, Talajic M, Zhu J, Pais P, Budaj A, Parkhomenko A, Jansky P, Commerford P, Tan RS, Sim KH, Lewis BS, Van Mieghem W, Lip GY, Kim JH, Lanas-Zanetti F, Gonzalez-Hermosillo A, Dans AL, Munawar M, O’Donnell M, Lawrence J, Lewis G, Afzal R, Yusuf S. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):806–817. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKellar SH, Abel S, Camp CL, Suri RM, Ereth MH, Schaff HV. Effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for thromboprophylaxis of mechanical heart valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(6):1410–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaeberich A, Reindl I, Raaz U, Maegdefessel L, Vogt A, Linde T, Steinseifer U, Perzborn E, Hauroeder B, Buerke M, Werdan K, Schlitt A. Comparison of unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, low-dose and high-dose rivaroxaban in preventing thrombus formation on mechanical heart valves: results of an in vitro study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;32(4):417–425. doi: 10.1007/s11239-011-0621-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van de Werf F, Brueckmann M, Connolly SJ, Friedman J, Granger CB, Hartter S, Harper R, Kappetein AP, Lehr T, Mack MJ, Noack H, Eikelboom JW. A comparison of dabigatran etexilate with warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves: the randomized, phase II study to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics of oral dabigatran etexilate in patients after heart valve replacement (REALIGN) Am Heart J. 2012;163(6):931–937. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Price J, Hynes M, Labinaz M, Ruel M, Boodhwani M. Mechanical valve thrombosis with dabigatran. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(17):1710–1711. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: anti-thrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(12):857–867. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Go AS, Hylek EM, Borowsky LH, Phillips KA, Selby JV, Singer DE. Warfarin use among ambulatory patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: the anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(12):927–934. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-12-199912210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hylek EM, D’Antonio J, Evans-Molina C, Shea C, Henault LE, Regan S. Translating the results of randomized trials into clinical practice: the challenge of warfarin candidacy among hospitalized elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Stroke. 2006;37(4):1075–1080. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000209239.71702.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, Hylek EM, Henault LE, Jensvold NG, Singer DE. Death and disability from warfarin-associated intracranial and extracranial hemorrhages. Am J Med. 2007;120(8):700–705. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Walraven C, Oake N, Wells PS, Forster AJ. Burden of potentially avoidable anticoagulant-associated hemorrhagic and thromboembolic events in the elderly. Chest. 2007;131(5):1508–1515. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corsonello A, Pedone C, Lattanzio F, Lucchetti M, Garasto S, Carbone C, Greco C, Fabbietti P, Incalzi RA. Regimen complexity and medication nonadherence in elderly patients. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5(1):209–216. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s4870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Easton JD, Lopes RD, Bahit MC, Wojdyla DM, Granger CB, Wallentin L, Alings M, Goto S, Lewis BS, Rosenqvist M, Hanna M, Mohan P, Alexander JH, Diener HC. Apixaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack: a subgroup analysis of the ARISTOTLE trial. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(6):503–511. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hankey GJ, Patel MR, Stevens SR, Becker RC, Breithardt G, Carolei A, Diener HC, Donnan GA, Halperin JL, Mahaffey KW, Mas JL, Massaro A, Norrving B, Nessel CC, Paolini JF, Roine RO, Singer DE, Wong L, Califf RM, Fox KA, Hacke W. Rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack: a subgroup analysis of ROCKET AF. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(4):315–322. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70042-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Diener HC, Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Wallentin L, Reilly PA, Yang S, Xavier D, Di Pasquale G, Yusuf S. Dabigatran compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous transient ischaemic attack or stroke: a subgroup analysis of the RE-LY trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(12):1157–1163. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70274-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alexander JH, Lopes RD, James S, Kilaru R, He Y, Mohan P, Bhatt DL, Goodman S, Verheugt FW, Flather M. Apixaban with antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(8):699–708. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Bassand JP, Bhatt DL, Bode C, Burton P, Cohen M, Cook-Bruns N, Fox KAA. Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(1):9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wann LS, Curtis AB, January CT, Ellenbogen KA, Lowe JE, Estes NA, III, Page RL, Ezekowitz MD, Slotwiner DJ, Jackman WM, Stevenson WG, Tracy CM, Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Le Heuzey JY, Crijns HJ, Lowe JE, Curtis AB, Olsson SB, Ellenbogen KA, Prystowsky EN, Halperin JL, Tamargo JL, Kay GN, Wann LS, Jacobs AK, Anderson JL, Albert N, Hochman JS, Buller CE, Kushner FG, Creager MA, Ohman EM, Ettinger SM, Stevenson WG, Guyton RA, Tarkington LG, Halperin JL, Yancy CW. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (updating the 2006 guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;123(1):104–123. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181fa3cf4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Caterina R, Husted S, Wallentin L, Andreotti F, Arnesen H, Bachmann F, Baigent C, Huber K, Jespersen J, Kristensen SD, Lip GY, Morais J, Rasmussen LH, Siegbahn A, Verheugt FW, Weitz JI. New oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and acute coronary syndromes: ESC working group on thrombosis-task force on anticoagulants in heart disease position paper. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(16):1413–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dewilde W, Berg JT. Design and rationale of the WOEST trial: What is the optimal antiplatElet and anticoagulant therapy in patients with oral anticoagulation and coronary StenTing (WOEST) Am Heart J. 2009;158(5):713–718. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dewilde W, Oirbans T, Verheugt FW, Kelder J, De Smet B, Herrman J, Adriaenssens T, Mathias V, Heestermans A, Vis M, Rasoul S, Sheikjoesoef K, Vandendriessche T, Cornelis K, Vos J, Brueren G, Breet N, ten Berg J. The WOEST Trial: First randomised trial comparing two regimens with and without aspirin in patients on oral anticoagulant therapy undergoing coronary stenting. Paper presented at the European Society of Cardiology; Munich, Germany. 28 Aug 2012.2012. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lip GY, Huber K, Andreotti F, Arnesen H, Airaksinen JK, Cuisset T, Kirchhof P, Marin F. Antithrombotic management of atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing coronary stenting: executive summary–a consensus document of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on thrombosis, endorsed by the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2010;31(11):1311–1318. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, Van Gelder IC, Al-Attar N, Hindricks G, Prendergast B, Heidbuchel H, Alfieri O, Angelini A, Atar D, Colonna P, De Caterina R, De Sutter J, Goette A, Gorenek B, Heldal M, Hohloser SH, Kolh P, Le Heuzey JY, Ponikowski P, Rutten FH. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the task force for the management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2010;31(19):2369–2429. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paikin JS, Wright DS, Crowther MA, Mehta SR, Eikelboom JW. Triple antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and coronary artery stents. Circulation. 2010;121(18):2067–2070. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.924944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baker WL, Phung OJ. Systematic review and adjusted indirect comparison meta-analysis of oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2012;5(5):711–719. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller CS, Grandi SM, Shimony A, Filion KB, Eisenberg MJ. Meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(3):453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lip GY, Larsen TB, Skjoth F, Rasmussen LH. Indirect comparisons of new oral anticoagulant drugs for efficacy and safety when used for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(8):738–746. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mantha S, Ansell J. An indirect comparison of dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban for atrial fibrillation. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(3):476–484. doi: 10.1160/TH12-02-0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schneeweiss S, Gagne JJ, Patrick AR, Choudhry NK, Avorn J. Comparative efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2012;5(4):480–486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.965988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harenberg J, Marx S, Diener HC, Lip GY, Marder VJ, Wehling M, Weiss C. Comparison of efficacy and safety of dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation using network meta-analysis. Int Angiol. 2012;31(4):330–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.MacLean S, Mulla S, Akl EA, Jankowski M, Vandvik PO, Ebrahim S, McLeod S, Bhatnagar N, Guyatt GH. Patient values and preferences in decision making for antithrombotic therapy: a systematic review: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e1S–e23S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]