Abstract

Objective: The objective of this article is to systematically analyse the randomized, controlled trials comparing transinguinal preperitoneal (TIPP) and Lichtenstein repair (LR) for inguinal hernia.

Methods: Randomized, controlled trials comparing TIPP vs LR were analysed systematically using RevMan® and combined outcomes were expressed as risk ratio (RR) and standardized mean difference.

Results: Twelve randomized trials evaluating 1437 patients were retrieved from the electronic databases. There were 714 patients in the TIPP repair group and 723 patients in the LR group. There was significant heterogeneity among trials (P < 0.0001). Therefore, in the random effects model, TIPP repair was associated with a reduced risk of developing chronic groin pain (RR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.26, 0.89; z = 2.33; P < 0.02) without influencing the incidence of inguinal hernia recurrence (RR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.36, 1.83; z = 0.51; P = 0.61). Risk of developing postoperative complications and moderate-to-severe postoperative pain was similar following TIPP repair and LR. In addition, duration of operation was statistically similar in both groups.

Conclusion: TIPP repair for inguinal hernia is associated with lower risk of developing chronic groin pain. It is comparable with LR in terms of risk of hernia recurrence, postoperative complications, duration of operation and intensity of postoperative pain.

Keywords: inguinal hernia, transinguinal preperitoneal mesh repair, Lichtenstein repair, chronic groin pain

INTRODUCTION

Mesh repair of inguinal hernia is the most common operation performed on general surgical patients. Approximately 20 million groin hernioplasties are performed each year worldwide, over 17 000 operations in Sweden, over 12 000 in Finland, over 80 000 in England and over 800 000 in the USA [1–4]. Countless studies have been reported in the medical literature in attempts to improve the overall outcomes following hernia operations and, due to this fact, the procedure has evolved immensely, especially over the last few decades. Recurrence of inguinal hernia was initially a significant problem; `however, with the advent of the tension-free mesh repair as described as Lichtenstein repair (LR) [5], recurrence rate has consistently been reported as low as 1–4% [6–10], a drop from up to 50–60%. Concomitant with this drop in the hernia recurrence rate, investigators and surgeons are facing other challenges, such as an increased incidence of chronic pain following LR. There are several controversies regarding definition of chronic pain but a relatively accepted definition has been put forth by the International Association for the Study of Pain and cited by Poobalan et al. [11], is pain that persists at the surgical site and nearby surrounding tissues beyond 3 months. However, persistence of surgical site pain at six months after surgery is also reported in few studies. Incidence of postoperative chronic groin pain ranges from 10–54% of patients following inguinal hernia operation [11–13]. The exact mechanism involved in the development of chronic groin pain following LR and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is still poorly understood but it is postulated to be multifactorial in origin. The etiological factors leading to post-operative chronic groin pain include inguinal nerve irritation by the sutures or mesh [14], inflammatory reactions against the mesh [15] or simply scarring in the inguinal region incorporating the inguinal nerves [16–18]. It may also be attributed to local tissue inflammatory reactions from foreign material, bio-incompatibility and abdominal wall compliance reduction [19]. In addition, fixation of the mesh during LR and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair is thought to contribute to postoperative chronic groin pain due to nerve injury ranging from 2–4% [20].

Transinguinal preperitoneal (TIPP) inguinal hernia repair with soft mesh has been reported as a safe anterior approach with a preperitoneal sutureless mesh position by using the annulus internus as an entrance to the preperitoneal space [21–23]. This open and sutureless technique has a short learning curve and it is also cost-effective compared to the laparoscopic total extraperitoneal preperitoneal technique [24]. Theoretically, TIPP repair may be associated with lesser chronic postoperative pain than Lichtenstein’s technique due to the placement of mesh in the preperitoneal space to avoid direct regional nerves dissection and their exposure to bio-reactive synthetic mesh. The placement of mesh in this plane without using any suture for fixation—and lack of mesh exposure to regional nerves—was assumed to result in the reduced risk of developing chronic groin pain. A recently published Cochrane review of two published and one unpublished randomized, controlled trials failed to provide adequate evidence in favour of TIPP repair due to lack of an optimum number of studies and recruited patients [25]. In addition, another recently reported meta-analysis of 12 studies (10 randomized, controlled trials and two comparative studies) confirmed the potential benefits of TIPP in terms of reduced risk of developing chronic groin pain with equivocal postoperative complications and risk of hernia recurrence [26]. This meta-analysis also failed to provide a conclusive statement because it included trials comparing LR against the Prolene™ Hernia System. Therefore, the objective of this review article is to systematically analyse the randomized, controlled trials comparing TIPP and LR of inguinal hernia with mesh and attempt to ascertain the role of TIPP in reducing the incidence of chronic groin pain without influencing the risk hernia recurrence and postoperative complications.

METHODS

Identification of trials

Randomized, controlled trials (irrespective of language, country of origin, hospital of origin, blinding, sample size or publication status) comparing TIPP vs LR approaches of open inguinal hernia repair were included in this review. We also included other trials in which mesh was placed in the preperitoneal space through an open inguinal incision approach. The Cochrane Colorectal Cancer Group (CCCG) Controlled Trials Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, Medline, Embase and Science Citation Index Expanded were searched for articles published up to October 2012 using the medical subject headings (MeSH) terms “inguinal hernia” and “groin hernia” in combination with free text search terms, such as “mesh repair of inguinal hernia”, “transinguinal preperitoneal repair”, “sutureless repair” and “open inguinal hernia repair”. A filter for identifying randomized, controlled trials recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration was used to filter out non-randomized studies in Medline and Embase [27]. The references from the included trials were searched to identify additional trials.

Data extraction

Two of the authors independently identified the trials for inclusion and exclusion and extracted the data. The accuracy of the extracted data was further confirmed by a third author. There were no discrepancies in the selection of the trials or in data extraction between the reviewers, except in the case of recording the severity of pain according to the measurement scales and timing of the recorded data. All reviewers agreed that blinding was impossible to achieve in the case of the operating surgeon. However, there was disagreement with regard to whether the trials should be classified as having a high or low risk of bias, based on four parameters, i.e. randomization technique, power calculations, blinding and intention-to-treat analysis. It was agreed that the lack of an adequate randomization technique and an intention-to-treat analysis would result in the trials being classified as having a high risk of bias. In case of any unclear or missing information, the reviewers planned to obtain those by contacting the authors of the individual trials.

Statistical analysis

The software package RevMan 5.1.2 [28], provided by the Cochrane Collaboration, was used for the statistical analysis to achieve a combined outcome. The risk ratio (RR) with a 95 per cent confidence interval (CI) was calculated for binary data and the standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95% CI was calculated for continuous data variables. The random-effects model was used to calculate the combined outcomes of both binary and continuous data [29, 30]. Heterogeneity was explored using the chi-squared test, with significance set at P < 0.05 and was quantified using I2 [31], with a maximum value of 30% identifying low heterogeneity [31]. The Mantel-Haenszel method was used for the calculation of RR under the random effect models [32]. In a sensitivity analysis, 0.5 was added to each cell frequency for trials in which no event occurred in either the treatment or control group, according to the method recommended by Deeks et al. [33]. If the standard deviation was not available, then it was calculated according to the guidelines of the Cochrane Collaboration [27]. This process involved assumptions that both groups had the same variance, which may not have been true, and variance was either estimated from the range or from the P-value. The estimate of the difference between both techniques was pooled, depending upon the effect weights in results determined by each trial estimate variance. A forest plot was used for the graphical display of the results. The square around the estimate stood for the accuracy of the estimation (sample size) and the horizontal line represented the 95% CI. The methodological quality of the included trials was initially assessed using the published guidelines of Jadad et al. and Chalmers et al. [34, 35]. Based on the quality of the included randomised, controlled trials, the strength and summary of the evidence was further evaluated by GradePro® [36], a tool provided by the Cochrane Collaboration. We classified chronic groin pain and recurrence as primary outcome measures. Duration of operation, postoperative pain and postoperative complications were analysed as secondary outcome measures.

RESULTS

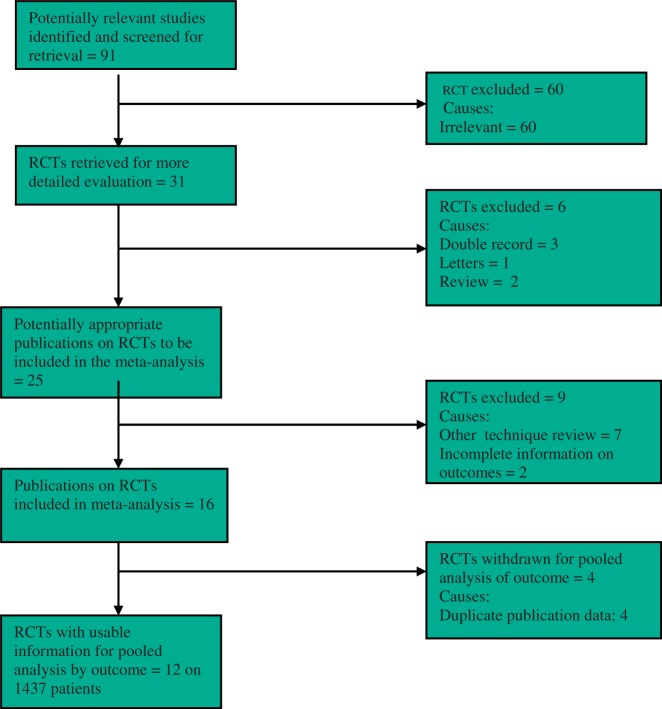

The PRISMA flow chart to explain the literature search strategy and trial selection is given in Figure 1. Twelve randomized, controlled trials evaluating 1437 patients were retrieved from commonly used standard medical electronic databases [37–48]. There were 714 patients in the TIPP repair group and 723 patients in the LR group. The characteristics of the included trials are given in Table 1. The salient features and treatment protocols adopted in the included randomized, controlled trials are given in Table 2. The short summary of data, selected primary and secondary outcome measures used to achieve a summated statistical effect, are given in Table 3. Three included trials [41, 42, 48] reported four study arms but their data pertaining to TIPP repair and LR was used exclusively for this analysis. Similarly we used data of TIPP repair and LR arm from another trial which reported five study arms [44]. We also included a trial [43] which recruited acute surgical patients of incarcerated inguinal undergoing TIPP repair vs LR. Subgroup analysis after excluding these trials favoured the principle conclusion of this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart showing trial selection methodology.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included trials

| Trial | Year | Country | Age in years | Male: Female | Duration of follow-up | Hernia details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berrevoet et al. [37] | ||||||

| TIPP | 2012 | Belgium | 18–65 | 142: 8 | 3 months | Primary inguinal hernia |

| LR | ||||||

| Dogru et al. [38] | months | |||||

| TIPP | 2006 | Turkey | 51.1 ± 16.2 | 134: 5 | 53.06 ± 5.6 | Primary inguinal hernia |

| LR | 50.1 ± 16.4 | 53.41 ± 7.1 | ||||

| Erhan et al. [39] | ||||||

| TIPP | 2008 | Turkey | 58.9 (36–82) | Males only | 12 months | Primary inguinal hernia |

| LR | 57.1 (17–85) | Recurrent inguinal hernia | ||||

| Farooq et al. [40] | ||||||

| TIPP | 2007 | Pakistan | 56.7 | Males only | 24 months | Primary inguinal hernia |

| LR | Recurrent inguinal hernia | |||||

| Gunal et al. [41] | ||||||

| TIPP | 2007 | Turkey | 23.85 ± 0.49 | Males only | 96 months | Primary inguinal hernia |

| LR | 22.76 ± 0.3 | |||||

| Hamza et al. [42] | ||||||

| TIPP | 2010 | Egypt | 35.67 ± 12.96 | Males only | 12 months | Primary inguinal hernia |

| LR | 35.12 ± 10.11 | |||||

| Karatepe et al. [43] | ||||||

| TIPP | 2008 | Turkey | 63 ± 20.1 | 31: 9 | 6–72 months | Primary inguinal hernia |

| LR | 60 ± 17.7 | 6–70 months | Recurrent inguinal hernia | |||

| Kawji et al. [44] | ||||||

| TIPP | 1999 | Austria | 57–72 | Mixed group | 18 months | Primary inguinal hernia |

| LR (5 arms) | 65 | |||||

| Koning et al. [45] | ||||||

| TIPP | 2012 | Netherlands | 57 ± 12.1 | 288: 14 | 12 months | Primary inguinal hernia |

| LR | 56.5 ± 13.2 | |||||

| Muldoon et al. [46] | ||||||

| TIPP | 2004 | USA | 60.7 (26–86) | Males only | 24 months | Primary inguinal hernia |

| LR | 63.3 (18–85) | |||||

| Nienhuijs et al. [47] | ||||||

| TIPP | 2007 | Netherlands | 55.6 ± 15.8 | 170: 2 | 3 months | Primary inguinal hernia |

| LR | 54 ± 13.6 | |||||

| Vatansev et al. [48] | ||||||

| TIPP | 2002 | Turkey | 50.7 ± 15.7 | 40: 5 | 1 week | Primary inguinal and femoral |

| LR | 53.2 ± 12.6 | hernia | ||||

TIPP = transinguinal preperitoneal hernia repair, LR = Liechtenstein repair.

Table 2.

Treatment protocol adopted in included trials

| Trial | Transinguinal preperitoneal hernia repair | Lichtenstein repair |

|---|---|---|

| Berrevoet et al. [37] |

|

|

| Dogru et al. [38] |

|

|

| Erhan et al. [39] |

|

|

| Farooq et al. [40] |

|

|

| Gunal et al. [41] |

|

|

| Hamza et al. [42] |

|

|

| Karatepe et al. [43] TIPP LR |

|

|

| Kawji et al. [44] |

|

|

| Koning et al. [45] |

|

|

| Muldoon et al. [46] |

|

|

| Nienhuijs et al. [47] |

|

|

| Vatansev et al. [48] |

|

|

TIPP = transinguinal preperitoneal hernia repair, LR = Liechtenstein repair, LA = local anaesthetic, GA = general anaesthetic.

Table 3.

Variables used for meta-analysis

| Trial | Patients (number: n) | Operation time (minutes ± SD) | Perioperative pain: 30 day (n) | Complications (n) | Chronic groin pain (n) | Recurrence (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berrevoet et al. [37]1 | ||||||

| TIPP | 75 | Not available | 5/75 | 2/75 | 2/72 | 3/72 |

| LR | 75 | 29/75 | 14/75 | 10/56 | 2/70 | |

| Dogru et al. [38] | ||||||

| TIPP | 69 | 45.36 ± 6.20 | Not investigated | 5 | 0 | 0/69 |

| LR | 70 | 47.06 ± 7.50 | 2 | 0 | 1/70 | |

| Erhan et al. [39] | ||||||

| TIPP | 24 | Not investigated | Not investigated | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| LR | 70 | 0 | 4 | 0 | ||

| Farooq et al. [40] | ||||||

| TIPP | 33 | 62.6 ± 18.4* | Not investigated | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| LR | 34 | 70.1 ± 18.4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gunal et al. [41]2 | ||||||

| TIPP | 39 | 36.54 ± 1.55 | 3.7 ± 1 | 9 | 0 | 1/39 |

| LR | 42 | 39.64 ± 1.28 | 4.8 ± 1.4 | 19 | 0 | 1/42 |

| Hamza et al. [42]2 | ||||||

| TIPP | 25 | 54.5 ± 13.2 | 4.93 ± 1.62 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| LR | 25 | 34 ± 23.5 | 4.63 ± 2.22 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Karatepe et al. [43] | ||||||

| TIPP | 19 | Not investigated | Not investigated | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| LR | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Kawji et al. [44]3 | ||||||

| TIPP | 21 | Not investigated | 2.2 ± 1.01 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| LR | 83 | 2.5 ± 1.9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Koning et al. [45] | ||||||

| TIPP | 143 | 34.1 ± 9.9 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 9 | 5 | 2 |

| LR | 159 | 39.9 ± 12.0 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | 29 | 20 | 4 |

| Muldoon et al. [46] | ||||||

| TIPP | 121 | Not investigated | 76/79 | 5/109 | 10/121 | 1/121 |

| LR | 126 | 83/86 | 4/115 | 9/126 | 5/126 | |

| Nienhuijs et al. [47] | ||||||

| TIPP | 86 | Not investigated | 39/78 2.8 ± 2.3 | 7/86 | 17/82 | 2/86 |

| LR | 85 | 50/78 2.8 ± 2.3 | 12/85 | 34/84 | 2/85 | |

| Vatansev et al. [48]2 | ||||||

| TIPP | 21 | 51.9 ± 6.5 | Not investigated | Not investigated | Not investigated | Not investigated |

| LR | 24 | 50.7 ± 15.3 |

*Standard deviation estimated from the P-value.

1 Data taken from the published Cochrane review [25]. 2 Four arms randomized, controlled trial. Data of TIPP and LR arms was used for combined analysis. 3 Five arms randomized, controlled trial. Data of TIPP and LR arms was used for combined analysis.

Methodological quality of included studies

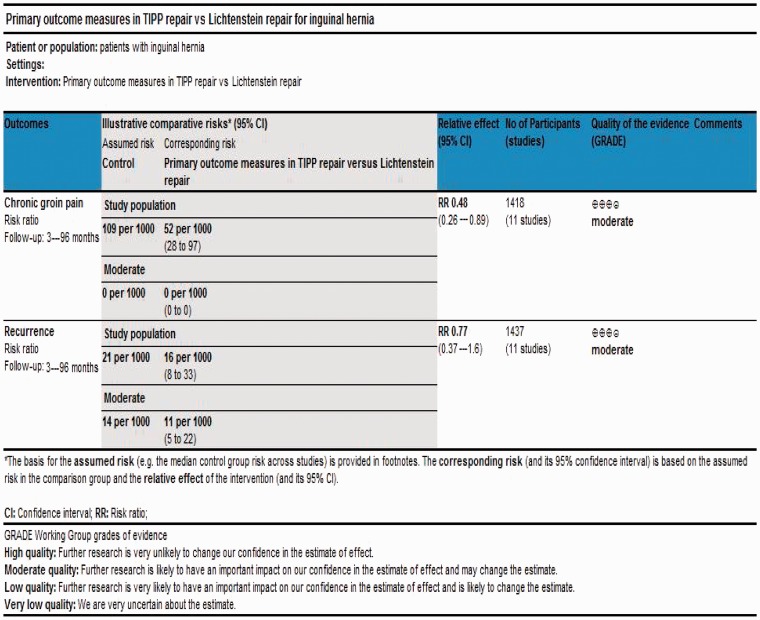

According to Jadad et al. and Chalmers et al. [34, 35] the quality of the majority of included trials [37–39, 41–44, 46–48] was low due to the inadequate randomization technique and absence of adequate allocation concealment, power calculations, blinding and intention-to-treat analysis [Table 4]. Based on the quality of included randomized controlled trials, the strength and summary of evidence analysed on GradePro® is given in Figure 2 [36].

Table 4.

Quality assessment of included trials

| Trial | Randomisation technique | Power calculations | Blinding | Intention-to-treat analysis | Allocation Concealment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berrevoet et al. [37] | Computer generated | Not available | No | Yes | Adequate |

| Dogru et al. [38] | Admission order | No | Unclear | No | Adequate |

| Erhan et al. [39] | Admission order | No | No | No | Inadequate |

| Farooq et al. [40] | Computer generated | Yes | Yes | No | Adequate |

| Gunal et al. [41] | Random allocation | No | No | No | Inadequate |

| Hamza et al. [42] | Random number allocation | No | Yes | No | Inadequate |

| Karatepe et al. [43] | Random tables | No | No | No | Adequate |

| Kawji et al. [44] | Unclear | No | No | No | Inadequate |

| Koning et al. [45] | Computer generated | Yes | Yes | Yes | Adequate |

| Muldoon et al. [46] | Computer generated series | No | No | No | Envelope based Adequate |

| Nienhuijs et al. [47] | Computer generated list | No | Yes | No | Adequate |

| Vatansev et al. [48] | Sealed envelops | No | No | No | Adequate |

Figure 2.

Strength and summary of the evidence analysed on GradePro®.

Primary outcome measures

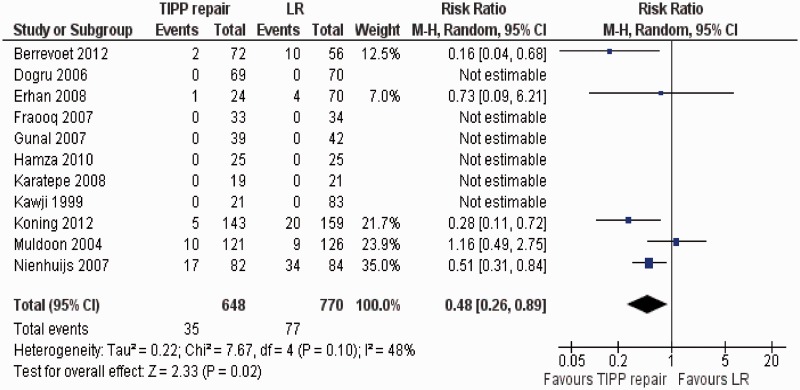

Chronic groin pain

Eleven randomized, controlled trials [37–47] contributed to the combined calculation of this variable. There was moderate heterogeneity among trials (Tau2 = 2.22, chi2 = 7.67, df = 4, [P = 0.10]; I2 = 48%). In the random effects model (RR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.26, 0.89; z = 2.33; P < 0.02: Figure 3), the risk of developing chronic groin pain following TIPP repair was lower compared to the use of LR.

Figure 3.

Forest plot for chronic groin pain following TIPP repair vs LR. Risk ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. TIPP = transinguinal preperitoneal, LR = Lichtenstein repair.

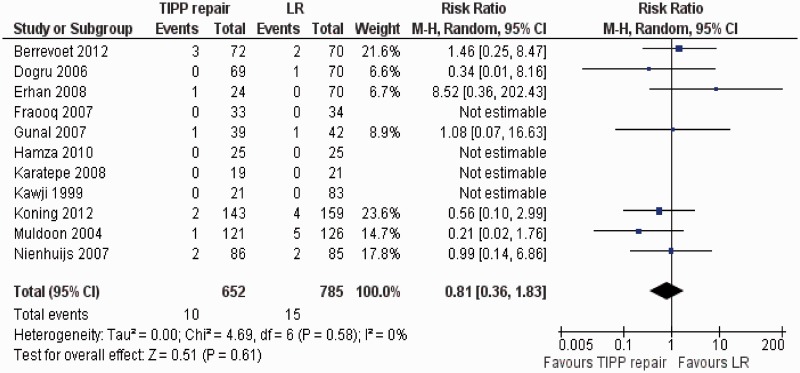

Recurrence

There was no heterogeneity among trials (Tau2 = 0.00, chi2 = 4.69, df = 6, [P = 0.58]; I2 = 0%). In the random effects model (RR, 0.18; 95% CI, 0.36, 1.83; z = 0.51; P = 0.61: Figure 4), the risk of developing recurrent inguinal hernia following TIPP repair and LR was statistically similar.

Figure 4.

Forest plot for recurrence following TIPP repair vs LR. Risk ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. TIPP = transinguinal preperitoneal, LR = Lichtenstein repair.

Secondary outcomes measures

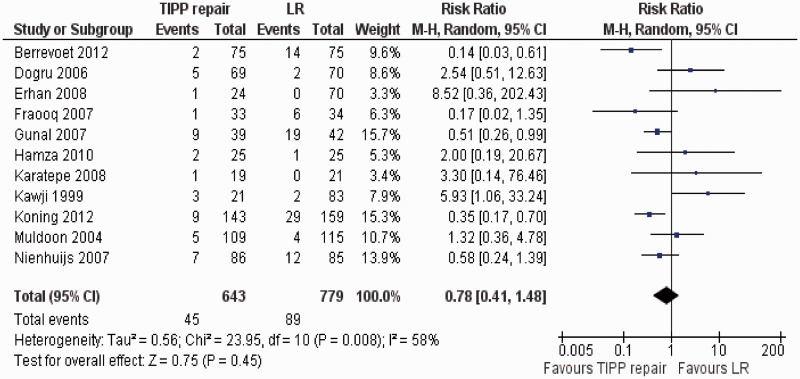

Postoperative complications

Eleven randomized, controlled trials [37–47] contributed to the combined calculation of this variable. There was moderate heterogeneity (Tau2 = 0.56, chi2 = 23.95, df = 10, [P = 0.008]; I2 = 58%) among trials. In the random effects model (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.41, 1.48; z = 0.75; P = 0.45; Figure 5), the risk of developing postoperative complications was statistically similar in both groups.

Figure 5.

Forest plot for postoperative complications following TIPP repair vs LR. Risk ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. TIPP = transinguinal preperitoneal, LR = Lichtenstein repair.

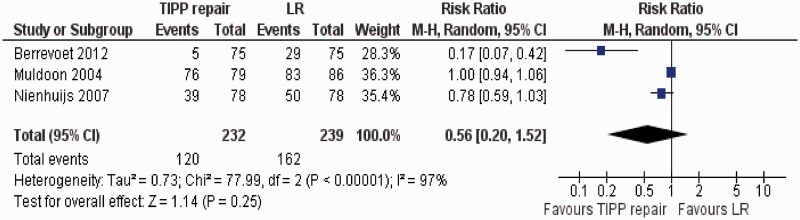

Postoperative incidence of moderate-to-severe pain

Three randomized, controlled trials [37, 46, 47] contributed to the combined calculation of this variable. There was significant heterogeneity (Tau2 = 0.73; chi2 = 77.99, df = 2, [P < 0.00001]; I2 = 97%) among trials. In the random effects model (RR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.20, 1.52; z = 1.14; P = 0.25; Figure 6), the incidence of postoperative moderate-to-severe pain was statistically similar in both groups.

Figure 6.

Forest plot for postoperative incidence of moderate to severe pain following TIPP repair vs LR. Risk ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. TIPP = transinguinal preperitoneal, LR = Lichtenstein repair.

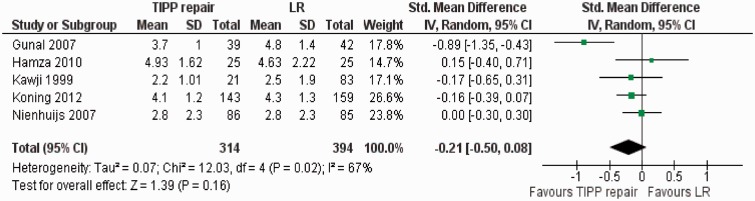

Postoperative intensity of pain

Five randomized, controlled trials [41, 42, 44, 45, 47] contributed to the combined calculation of this variable. There was significant heterogeneity (Tau2 = 0.07; chi2 = 12.03, df = 4, [P < 0.02]; I2 = 67%) among trials. In the random effects model (SMD, −0.21; 95% CI, −0.50, 0.08; z = 1.39; P = 0.16; Figure 7), the postoperative pain score in both groups was similar.

Figure 7.

Forest plot for postoperative pain intensity following TIPP repair vs LR. Standardized mean difference (SMD) is shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. TIPP = transinguinal preperitoneal, LR = Lichtenstein repair.

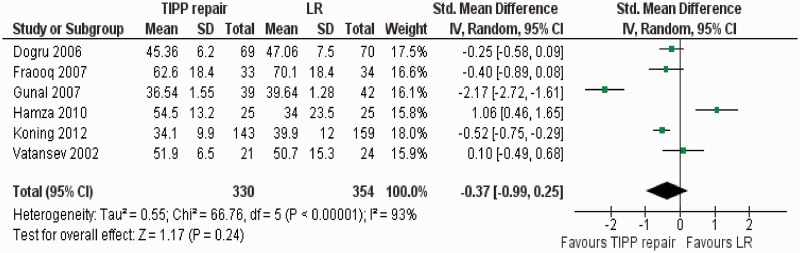

Duration of operation

There was significant heterogeneity (Tau2 = 0.55; chi2 = 66.76, df = 5, [P < 0.00001]; I2 = 93%) among trials. Therefore, in the random effects model (SMD, −0.37; 95% CI, −0.99, 0.25; z = 1.17; P = 0.24; Figure 8), the duration of operation for TIPP repair and LR was statistically similar.

Figure 8.

Forest plot for duration of operation following TIPP repair vs LR. Standardized mean difference (SMD) is shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. TIPP = transinguinal preperitoneal, LR = Lichtenstein repair.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review demonstrates that TIPP repair was associated with a reduced risk of developing chronic groin pain and similar risk of inguinal hernia recurrence, compared to LR. Risk of developing postoperative complications and moderate-to-severe postoperative pain was similar following TIPP repair and LR. In addition, duration of operation was statistically similar in both groups. Findings of this analysis are in concordance with the two previously published systematic reviews [25, 26]. However, these reviews provided limited conclusions, due to methodological flaws and paucity of randomized, controlled trials. Willaert et al. [25] reported a meta-analysis of two published and one unpublished, randomized, controlled trials and failed to provide substantial evidence in favour of TIPP repair, due to lack of optimum number of studies and recruited patients [25]. In addition, Li et al. [26] reported a systematic review of 12 studies (10 randomized, controlled trials and two comparative studies) which quoted the potential benefits of TIPP in terms of reduced risk of developing chronic groin pain with equivocal postoperative complications and risk of hernia recurrence. But that review also failed to provide a conclusive statement because five included trials were comparing LR against Prolene™ Hernia System leading to potential biases in the inclusion criteria. The present review is reporting the combined conclusion of only those trials which compared the placement of mesh on posterior wall of the inguinal canal against the placement of mesh in the preperitoneal space and, therefore, provides adequate evidence in favour of TIPP repair. TIPP repair may be considered a viable alternative to LR due to its proven advantages in this review.

There are several limitations to the present review. There were significant differences in inclusion and exclusion criteria among the included randomized, controlled trials, such as the recruitment of unilateral inguinal hernia, bilateral inguinal hernia, recurrent inguinal hernia and femoral hernia. Further sub-classification of the inguinal hernia in the form of direct and indirect was also not considered at the time of patient selection. Varying degrees of differences also existed among included randomized, controlled trials regarding the definitions of ‘chronic groin pain’ and ‘measurement scales for postoperative pain’. Randomized, controlled trials [40–43, 48] with fewer patients in this review may not have been sufficient to recognise small differences in outcomes. Included trials with more than two treatment arms [41, 42, 44, 48] may also be considered a biased approach for inclusion. Mesh fixation techniques were a noticeable confounding variable among included trials. Trials in the LR group were not homogenous in terms of mesh fixation technique and, therefore, are potential sources of bias. In addition, in the TIPP group, three studies [39, 40, 46] also reported suture mesh fixation [Table 2] whereas, in the remaining trials in this group, mesh was not fixed. Quality of included trials was poor due to inadequate randomization technique, allocation concealment, power calculations, blinding and intention-to-treat analysis [Table 4]. Variables like foreign body sensation, groin stiffness and decreased groin compliance should have been considered because displaced and rolled-up mesh is likely to cause these symptoms. Our conclusion is based on the summated outcome of 12 randomized, controlled trials but it should be considered with caution because the quality of the majority of included trials was low. There is still a lack of stronger evidence to support the routine use of TIPP repair but it can be considered an alternative and may be applied in selected groups of patients in the beginning. A major, multi-centre, randomized, controlled trial of high quality, according to CONSORT guidelines, is mandatory to validate these findings.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heikkinen TJ, Haukipuro K, Hulkko A. A cost and outcome comparison between laparoscopic and Lichtenstein hernia operations in a day-case unit. A randomized prospective study. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1199–203. doi: 10.1007/s004649900820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheek CM, Black NA, Devlin HB. Groin hernia surgery: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1998;80(Suppl 1):S1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutkow IM. Demographic and socioeconomic aspects of hernia repair in the United States in 2003. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83:1045–51. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(03)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swedish Hernia Register. http://www.svensktbrackregister.se (10 June 2007, date last accessed)

- 5.Amid PK. Lichtenstein tension-free hernioplasty: its inception, evolution and principles. Hernia. 2004;8:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10029-003-0160-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heikkinen T, Bringman S, Ohtonen P, et al. Five-year outcome of laparoscopic and Lichtenstein hernioplasties. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:518–22. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lepere M, Benchetrit S, Debaert M, et al. A multicentric comparison of transabdominal versus totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic hernia repair using PARIETEX meshes. J Soc Laparoendosc Surg. 2000;4:147–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olmi S, Erba L, Magnone S, et al. Prospective study of laparoscopic treatment of incisional hernia by means of the use of composite mesh: indications, complications, mesh fixation materials and results (in Italian) Chir Ital. 2005;57:709–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacFadyen BV, Jr, Mathis CR. Inguinal herniorrhaphy: complications and recurrences. Semin Laparosc Surg. 1994;1:128–40. doi: 10.1053/SLAS00100128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCormack K, Scott NW, Go PM, et al. Laparoscopic techniques versus open techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database. 2003;1:CD001785. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poobalan AS, Bruce J, King PM, et al. Chronic pain and quality of life following open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1122–26. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callesen T, Bech K, Kehlet H. Prospective study of chronic pain after groin hernia repair. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1528–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bay-Nielsen M, Perkins FM, Kehlet H. Danish Hernia Database. Pain and functional impairment 1 year after inguinal herniorrhaphy: a nationwide questionnaire study. Ann Surg. 2001;233:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200101000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heise CP, Starling JR. Mesh inguinodynia: a new clinical syndrome after inguinal herniorrhaphy? J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:514–18. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Vita G, Milano S, Frazzetta M, et al. Tension-free hernia repair is associated with an increase in inflammatory response markers against the mesh. Am J Surg. 2000;180:203–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00445-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nahabedian MY, Dellon AL. Outcome of the operative management of nerve injuries in the ilioinguinal region. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:265–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris-Stiff GJ, Hughes LE. The outcomes of non-absorbable mesh placed within the abdominal cavity: literature review and clinical experience. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:352–67. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stulz P, Pfeiffer KM. Peripheral nerve injuries resulting from common surgical procedures in the lower portion of the abdomen. Arch Surg. 1982;117:324–27. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380270042009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klinge U, Klosterhalfen B, Müller M, et al. Foreign body reaction to meshes used for the repair of abdominal wall hernias. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:665–73. doi: 10.1080/11024159950189726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lantis JC, 2nd, Schwaitzberg SD. Tack entrapment of the ilioinguinal nerve during laparoscopic hernia repair. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1999;9:285–89. doi: 10.1089/lap.1999.9.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schumpelick V, Arlt G. Transinguinal preperitoneal mesh-plasty in inguinal hernia using local anesthesia. Chirurg. 1996;67:419–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pélissier EP, Blum D, Marre D, et al. Inguinal hernia: a patch covering only the myopectineal orifice is effective. Hernia. 2001;5:84–87. doi: 10.1007/s100290100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pélissier EP. Inguinal hernia: preperitoneal placement of a memory-ring patch by anterior approach. Preliminary experience. Hernia. 2006;10:248–52. doi: 10.1007/s10029-006-0079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koning GG, Koole D, de Jongh MAC, et al. The transinguinal preperitoneal hernia correction vs Lichtenstein’s technique; is TIPP top? Hernia. 2011;15:19–22. doi: 10.1007/s10029-010-0744-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willaert W, De Bacquer D, Rogiers X, et al. Open Preperitoneal Techniques vs Lichtenstein Repair for elective Inguinal Hernias. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD008034. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008034.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Ji Z, Li Y. Comparison of mesh-plug and Lichtenstein for inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hernia. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10029-012-0974-6. Jul 28. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Higgins JPT, Green S (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.0 (updated February 2008). http://www.cochrane-handbook.org [accessed 20 August 2011]

- 28. Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.0. The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration: Copenhagen, 2008.

- 29.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeMets DL. Methods for combining randomized clinical trials: strengths and limitations. Stat Med. 1987;6:341–50. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780060325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG. Systematic reviews in healthcare. London: BMJ Publishing, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Bradburn MJ. Statistical methods for examining heterogeneity and combining results from several studies in meta-analysis. In: Egger M, Smith GD, Altman DG, editors. Systemic reviews in health care: meta-analysis in context. 2nd edn. London: BMJ Publication Group; 2001. pp. 285–312. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chalmers TC, Smith H, Jr, Blackburn B, et al. A method for assessing the quality of a randomized control trial. Control Clin Trials. 1981;2:31–49. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(81)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cochrane IMS. http://ims.cochrane.org/revman/other-resources/gradepro/download (9 October 2012, date last accessed)

- 37.Berrevoet F- NCT00323673-unpublished data. Data for combined analysis was taken from the published Cochrane review cited as Willaert W, De Bacquer D, Rogiers X, Troisi R, Berrevoet F. Open Preperitoneal Techniques versus Lichtenstein Repair for elective Inguinal Hernias. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD008034. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008034.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dogru O, Girgin M, Bulbuller N, et al. Comparison of Kugel and Lichtenstein operations for inguinal hernia repair: results of a prospective randomized study. World J Surg. 2006;30:346–50. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0408-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erhan Y, Erhan E, Aydede H, et al. Chronic pain after Lichtenstein and preperitoneal (posterior) hernia repair. Can J Surg. 2008;51:383–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farooq O, Batool Z, Din AU, et al. Anterior tension - free repair versus posterior preperitoneal repair for recurrent hernia. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007;17:465–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Günal O, Ozer S, Gürleyik E, et al. Does the approach to the groin make a difference in hernia repair? Hernia. 2007;11:429–34. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamza Y, Gabr E, Hammadi H, et al. Four-arm randomized trial comparing laparoscopic and open hernia repairs. Int J Surg. 2010;8:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karatepe O, Adas G, Battal M, et al. The comparison of preperitoneal and Lichtenstein repair for incarcerated groin hernias: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Surg. 2008;6:189–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawji R, Feichter A, Fuchsjager N, et al. Postoperative pain and return to activity after five different types of inguinal herniarrhaphy. Hernia. 1999;3:31–35. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koning GG, Keus F, Koeslag L, et al. Randomized clinical trial of chronic pain after the transinguinal preperitoneal technique compared with Lichtenstein's method for inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1365–73. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muldoon RL, Marchant K, Johnson DD, et al. Lichtenstein vs anterior preperitoneal prosthetic mesh placement in open inguinal hernia repair: a prospective, randomized trial. Hernia. 2004;8:98–103. doi: 10.1007/s10029-003-0174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nienhuijs S, Staal E, Keemers-Gels M, et al. Pain after open preperitoneal repair vs Lichtenstein repair: a randomized trial. World J Surg. 2007;31:1751–57. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vatansev C, Belviranli M, Aksoy F, et al. The effects of different hernia repair methods on postoperative pain medication and CRP levels. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12:243–46. doi: 10.1097/00129689-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]