Abstract

The immune stimulatory cytokine interleukin-15 was recognized as one of the most promising cancer cure drug in an NIH guided review and is currently in clinical trial alone or as an adjuvant for certain types of metastatic solid tumors. IL-15 is an essential survival factor for natural killer (NK), natural killer-like T (NKT), and CD44hi memory CD8 T cells. The bioactivity of IL-15 in vivo is conferred mainly through a trans-presentation mechanism in which IL-15 is presented in complex with the α-subunit of soluble IL-15 receptor (IL-15R) to NK, NKT or T cells rather than directly interacts with membrane-bound IL-15R. With these understandings, recent studies have been focused on generating IL-15 agonists which consist of IL-15 and partial or whole of soluble IL-15R to improve its in vivo bioactivity. This minireview will summarize the key features of IL-15 as a potential cancer treatment cytokine and the most recent development of IL-15 agonists and preclinical studies. Critical milestones to translate the pre-clinical development to in-patients treatment are emphasized.

Keywords: Interleukin-15, Cytokine, Cancer therapy

The γ-chain family cytokine IL-15 has long been recognized to be growth promoting cytokine for NK, NKT, and memory CD8 T cells in vivo (1, 2) and considered one of the most promising drugs that can cure cancer in an NIH cancer treatment review (3). IL-15 functions through the trimeric IL-15 receptor complex, which consists of a high affinity unique binding IL- 15Rα chain that confers receptor specificity for IL-15 and the common IL-15Rβ and γ-chains (also known as IL-2Rβ/γ) shared with IL-2. Although IL-2 is currently the only FDA approved cytokine for cancer therapy, IL-15 has superior advantage in cancer treatment over IL-2 including: 1) low toxicity with improved efficacy in stimulation NK cell proliferation and sustaining memory CD8 T cells (4-6); 2) supporting the survival effector CD8 T cell instead of promoting activation-induced cell death (AICD) (7); 3) priming NK cell target-specific activation by upregulating signaling of the NK cell activating receptor NKG2D (8, 9); 4) important but not last, not inducing expansion of regulatory T cells (10); 5) lastly, IL-15 has recently been shown to have the ability to direct differentiation of cancer stem cells (CSC), at least in renal cell carcinoma model (11). Due to these unique features, IL-15 has been exploited extensively in the current years as a potential cancer treatment drug. Recombinant human IL-15 (rhIL-15) either alone or in combination with other regimens has entered phase I/II clinical trials for treating various types of cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Current clinical trials with IL-15 for cancer therapy

| Trial No. | Malignancy | Intervention | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01021059 | Refractory metastatic malignant melanoma and metastatic renal cell carcinoma |

rhIL-15 given intravenously once a day for 12 consecutive days, for a total of twelve doses of the drug |

Phase I to determine safety |

| NCT 01369888 | Metastatic Melanoma | rhIL-15 given intravenously once a day for 12 consecutive days following a non- myeloablative lymphocyte depleting chemotherapy regimen and adoptive transfer of regenerated tumor infiltrated lymphocytes (TILs) |

Phase I/II to determine safety and efficacy |

| NCT01727076 | Advanced melanoma, kidney cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, or head and neck cancer |

rhIL-15 given subcutaneously daily on days 1-5 and 8-12. Treatment repeats every 28 days for up to 4 courses in the absence of disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. |

Phase I to determine side effect and optimal dose |

| NCT01385423 | Refractory acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) |

rhIL-15 given intravenously once a day for 12 consecutive days after haploidentical donor NK cell transplant |

Phase I to determine safety |

| NCT01572493 | Adult with various metastatic cancer |

rhIL-15 given intravenously once a day for 10 consecutive days |

Phase I to determine side effects |

The most uniqueness of IL-15 among other therapeutic cytokines is its trans-presentation signaling mechanisms in which IL-15Rα from one subset of cells presents IL-15 to neighboring NK cells and/or CD44hi memory CD8 T cells which express only IL-15Rβ/γ receptor (12). Trans-presentation is currently thought to be the major mechanism by which IL-15 exerts its biological effects in vivo (12, 13). Indeed, IL-15 was found to be presented normally in the circulation of both human and mice in the format of heterodimer with sIL-15Rα (14, 15). The trans-presentation concept has been exploited in improving the therapeutic efficacy of IL-15.

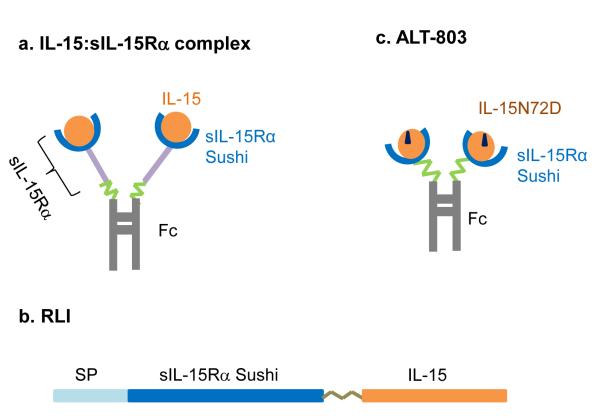

IL-15 monomer has a short half-life of less than 40 min in vivo and also weak binding affinity to sIL-15Rα for trans-presentation (16). These aspects may limit its therapeutic potential. Recent studies have been focused on generating modified forms of IL-15 agonist to improve the in vivo pharmacokinetics and ability for trans-presentation of IL-15. To date three main modifications are being pursued in pre-clinical treatment of cancer (Fig. 1): 1) pre-association of IL-15 and its soluble receptor a-subunit-Fc fusion to form IL-15:IL-15Rα-Fc complex (Fig. 1a) (17-20); 2) expression of the hyperagonist IL-15-sIL-15Rα-sushi fusion protein consisted of IL-15 and the recombinant soluble sushi domain of IL-15Rα which was identified to have the most binding affinity for IL-15 (Fig. 1b) (21, 22); 3) pre-association of human IL-15 mutant IL-15N72D (residue substitution at position 72) with IL-15Rα sushi-Fc fusion complex (Fig 1c) (23). All three forms of agonists showed these common improved features than native IL-15 in vivo: prolonged half-life and higher potency due to effective trans-presentation.

Figure 1.

Schematic depiction of three forms of IL-15 agonist. a, IL-15:sIL-15Rα complex. b, RLI, a fusion polypeptide of IL-15 and IL-15Rα Sushi domain. c, ALT-803, a complex of IL-15 mutant IL-15N72D with the Sushi domain of IL-15Rα.

All three forms of IL-15 agonist have shown superior anti-tumor activity than native IL-15. Administration of the IL-15:sIL-15Rα-Fc complex dramatically reduce tumor burden in B16 melanoma mouse model through enhanced proliferation and activity of NK cells and CD44hi memory CD8 T cells (18). In a different study, the IL-15:IL-15-Rα-Fc complex was also shown to be able to promote destruction of established primary B16F10 melanoma and pancreatic tumors by reviving tumor-resident CD8 T cells (12). The IL-15 hyperagonist, IL-15-sIL-15Rα-sushi fusion protein consisting of IL-15 and the recombinant soluble sushi domain of IL-15Rα which bears most of the binding affinity for IL-15, was shown to be more effective than IL-15 in reducing metastasis of B16F10 melanoma and enhancing host survival (3). RLI has nearly 20-fold of bioactivity binding to IL-15Rβ/γ than native IL-15 and a half-life of 3h in vivo (3). In in vitro assay, RLI showed more potency and persistent effect in stimulating lymphocyte proliferation, largely due to its ability to trans-present IL-15 (16, 17). The latest hIL-15N72D: hIL-15Rα sushi-Fc fusion complex (also named ALT-803) developed by Altor BioScience Corporation, has a residue substitution in IL-15 polypeptide at position 72 (asparagine to aspartic acid, hIL-15N72D) with improved binding affinity of IL-15/IL-15Rα complex to IL-15Rβ/γ. In this complex, hIL-15N72D only associates with the sushi-domain of hIL-15Rα. A single dose of ALT-803 was able to eliminate well-established myeloma cells in the bone-marrow of myeloma-bearing mice. Beyond the immediate therapeutic effect, these mice were able to reject re-challenge with the same tumor types due to expansion of CD44hi memory CD8 T cells (24). ALT-803 has at least 25 times the activity of the native IL-15 and 25 h of half-life in mice. These studies strongly support the notion that IL-15 agonists in combination with other regimens may provide curative future for cancer patients. ALT-803 will soon be in phase I/II clinical trial for treating relapse of hematologic malignancy after allogeneic stem cell transplant (NCT01885897) and advanced melanoma (NCT01946789).

By principle, all three forms have more potent immune stimulatory effect than the cytokine IL-15 due to the ability of trans-presentation. Which of the three forms of IL-15 agonists are more optimal for cancer treatment with least systemic toxicity is presently unknown. As IL-15 is also a pro-inflammatory cytokine and also play an important role in autoimmune diseases. Elevated serum IL-15 level or aberrant IL-15 signaling has been associated with several autoimmune diseases, including pemphigus vulgaris, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosis, sarcoidosis, multiple sclerosis, celiac disease, as well IBD (25, 26). Mice with aberrant overexpression of IL-15 in mice were reported to develop hematological malignancy (27-29). This suggests that long-term treatment with IL-15 may bear the risk of developing autoimmune diseases. Moreover, a number of studies have shown that IL-15 or soluble IL-15Rα also plays a role in triggering cancer cell, best exemplified in renal cell carcinoma, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is considered a critical step for cancer cell metastasis (30-32). With these in mind, the choice of IL-15 agonist and the optimal treatment platform have to be carefully investigated in the coming years with the goal to achieve an effective treatment with controlled autoimmunity.

Acknowledgement

Supported by NIH grant 1R01CA149405 and A. David Mazzone — PCF Challenge Award to J.D. Wu. Thanks to John Jarzen for helping with the Figure drawings.

References

- 1.Kennedy MK, Glaccum M, Brown SN, Butz EA, Viney JL, et al. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;191:771–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lodolce JP, Burkett PR, Boone DL, Chien M, Ma A. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2001;194:1187–94. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.8.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheever MA. Immunological reviews. 2008;222:357–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munger W, DeJoy SQ, Jeyaseelan R, Sr., Torley LW, Grabstein KH, et al. Cellular immunology. 1995;165:289–93. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldmann TA, Lugli E, Roederer M, Perera LP, Smedley JV, et al. Blood. 2011;117:4787–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sneller MC, Kopp WC, Engelke KJ, Yovandich JL, Creekmore SP, et al. Blood. 2011;118:6845–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marks-Konczalik J, Dubois S, Losi JM, Sabzevari H, Yamada N, et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:11445–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200363097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang C, Zhang J, Niu J, Tian Z. Cytokine. 2008;42:128–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decot V, Voillard L, Latger-Cannard V, Aissi-Rothe L, Perrier P, et al. Experimental hematology. 2010;38:351–62. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger C, Berger M, Hackman RC, Gough M, Elliott C, et al. Blood. 2009;114:2417–26. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-189266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azzi S, Bruno S, Giron-Michel J, Clay D, Devocelle A, et al. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2011;103:1884–98. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dubois S, Mariner J, Waldmann TA, Tagaya Y. Immunity. 2002;17:537–47. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00429-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi H, Dubois S, Sato N, Sabzevari H, Sakai Y, et al. Blood. 2005;105:721–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chertova E, Bergamaschi C, Chertov O, Sowder R, Bear J, et al. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:18093–103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.461756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergamaschi C, Bear J, Rosati M, Beach RK, Alicea C, et al. Blood. 2012;120:e1–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-10-384362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perdreau H, Mortier E, Bouchaud G, Sole V, Boublik Y, et al. European cytokine network. 2010;21:297–307. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2010.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoklasek TA, Schluns KS, Lefrancois L. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:6072–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubois S, Patel HJ, Zhang M, Waldmann TA, Muller JR. Journal of immunology. 2008;180:2099–106. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Epardaud M, Elpek KG, Rubinstein MP, Yonekura AR, Bellemare-Pelletier A, et al. Cancer research. 2008;68:2972–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubinstein MP, Kovar M, Purton JF, Cho JH, Boyman O, et al. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:9166–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600240103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mortier E, Quemener A, Vusio P, Lorenzen I, Boublik Y, et al. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:1612–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508624200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bessard A, Sole V, Bouchaud G, Quemener A, Jacques Y. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2009;8:2736–45. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu X, Marcus WD, Xu W, Lee HI, Han K, et al. Journal of immunology. 2009;183:3598–607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu W, Jones M, Liu B, Zhu X, Johnson CB, et al. Cancer research. 2013;73:3075–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Sabatino A, Calarota SA, Vidali F, Macdonald TT, Corazza GR. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2011;22:19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Budagian V, Bulanova E, Paus R, Bulfone-Paus S. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2006;17:259–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fehniger TA, Suzuki K, Ponnappan A, VanDeusen JB, Cooper MA, et al. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2001;193:219–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato N, Sabzevari H, Fu S, Ju W, Petrus MN, et al. Blood. 2011;117:4032–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-307504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mishra A, Liu S, Sams GH, Curphey DP, Santhanam R, et al. Cancer cell. 2012;22:645–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giron-Michel J, Azzi S, Khawam K, Caignard A, Devocelle A, et al. Bulletin du cancer. 2011;98:32–9. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2011.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khawam K, Giron-Michel J, Gu Y, Perier A, Giuliani M, et al. Cancer research. 2009;69:1561–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giron-Michel J, Azzi S, Khawam K, Mortier E, Caignard A, et al. PloS one. 2012;7:e31624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]