To the editor:

Statins and aspirin are widely prescribed medications that have long been associated with improved survival outcome in patients with various types of cancers.1,2 Both statins and aspirin were found to induce apoptosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells.3,4 The intake of statins and aspirin was associated with reduced incidence of CLL.5,6 However, statin intake did not affect treatment-free survival in patients with early CLL.7,8 Whether statin or aspirin use will benefit patients with advanced CLL is unknown.

Therefore, we retrospectively investigated the clinical outcome of patients with relapsed/refractory CLL treated with salvage fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR)9 with or without concomitant statins, aspirin, or both. We analyzed 280 patients who received salvage FCR between 1999 and 2012. The patients’ median age was 59 years (range: 31-84). The median progression-free survival (PFS) of all patients was 1.7 years, and the median overall survival (OS) was 4.0 years. Of the 280 patients, 58 patients received statins, aspirin, or both; 21 (8%) were taking aspirin only; 17 (6%) statins only; and 20 (7%) used both for at least 1 month prior to, during, and 1 month after salvage therapy. Among statin users, 15 patients (41%) were using atorvastatin, 12 patients (32%) were using simvastatin, 7 patients (19%) were using pravastatin, 2 patients (5%) were using rosuvastatin, and 1 patient (3%) was using lovastatin. Clinical characteristics of statin and/or aspirin users were similar to those of nonusers except for age. Patients on both statin and aspirin were 6 years older than nonusers (P < .01).

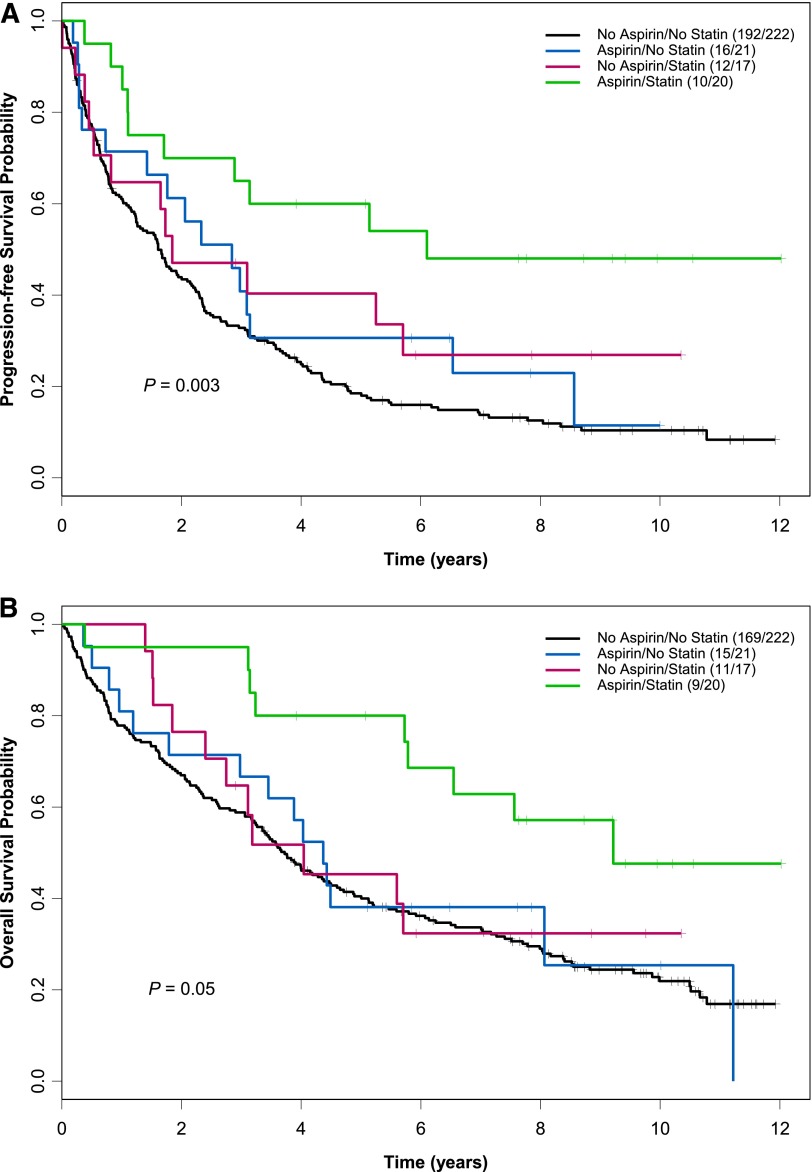

The overall response rate of patients receiving statins and aspirin concomitantly was superior (100%; 40% complete response, 60% partial response) to that of other patients (81% for aspirin-only users, 82% for statin-only users, and 72% for those who took neither drug; P < .01). Early death (during chemotherapy and up to 6 weeks afterward) was not observed in patients receiving aspirin, statins, or both but occurred in 6% of nonusers. Patients receiving both statins and aspirin had median PFS and OS of 6.1 and 9.2 years, respectively, compared with 1.6 years and 3.7 years in nonusers (PFS P = .003; OS P = .05; Figure 1). Compared with nonusers, patients who took both statins and aspirin had a 66% reduced risk of disease progression and a 60% reduced risk of death (PFS hazard ratio [HR] = 0.34, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.18-0.65, P < .001; OS HR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.21-0.79, P = .008).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates for PFS and OS by aspirin and statin use. Patients receiving both statins and aspirin (n = 20) had a median PFS (A) and OS (B) of 6.1 years and 9.2 years compared with 1.6 years and 3.7 years for patients on neither medication (n = 221) (PFS P = .003; OS P = .05). The number of events per total number of patients is denoted in the box. The P value was derived from a log-rank test.

In a fitted multivariate model controlling for clinicopathological characteristics found to be statistically significant from univariate analyses including Rai stage, cytogenetic abnormalities, the number of previous treatments, refractoriness to fludarabine, IgVH mutation status, β2-microglobulin, hemoglobin, platelet, lactate dehydrogenase, and creatinine level, use of both medications was also associated with a much more favorable outcome (PFS adjusted HR = 0.27, 95% CI = 0.14-0.53, P ≤ .001; OS adjusted HR = 0.29, 95% CI = 0.15-0.58, P < .001), whereas single-agent use of aspirin or statins did not affect PFS or OS.

Our findings demonstrate for the first time that concurrent administration of statins and aspirin to CLL patients with relapsed/refractory disease receiving salvage FCR significantly improve both response rate and survival. This is consistent with previous preclinical studies suggesting the possible synergistic effect between statins and chemotherapy.10 Therefore, a prospective study aimed at evaluating the effects of statins and aspirin in CLL patients receiving chemoimmunotherapy is warranted.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.K.C. and L.T. designed and performed research and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; X.W. performed statistical analysis; J.P., U.R., and W.G.W. revised the manuscript; and M.J.K. and Z.E. designed and supervised research and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Zeev Estrov, Department of Leukemia, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1400 Holcombe Blvd, Unit 428, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: zestrov@mdanderson.org.

References

- 1.Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG, Bojesen SE. Statin use and reduced cancer-related mortality. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(19):1792–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1201735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thun MJ, Jacobs EJ, Patrono C. The role of aspirin in cancer prevention. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9(5):259–267. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellosillo B, Piqué M, Barragán M, et al. Aspirin and salicylate induce apoptosis and activation of caspases in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 1998;92(4):1406–1414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapman-Shimshoni D, Yuklea M, Radnay J, Shapiro H, Lishner M. Simvastatin induces apoptosis of B-CLL cells by activation of mitochondrial caspase 9. Exp Hematol. 2003;31(9):779–783. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bracci PM. Use of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl Coenzyme-A Reductase Inhibitors (statins), Genetic Polymorphisms in Immunomodulatory and Inflammatory Pathways and Risk of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma [dissertation]. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley; 2007.

- 6.Kasum CM, Blair CK, Folsom AR, Ross JA. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of adult leukemia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(6):534–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman DR, Magura LA, Warren HA, Harrison JD, Diehl LF, Weinberg JB. Statin use and need for therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(12):2295–2298. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.520050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanafelt TD, Rabe KG, Kay NE, et al. Statin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in relation to clinical outcome among patients with Rai stage 0 chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(7):1233–1240. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.486877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wierda W, O’Brien S, Wen S, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab for relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(18):4070–4078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Podhorecka M, Halicka D, Klimek P, Kowal M, Chocholska S, Dmoszynska A. Simvastatin and purine analogs have a synergic effect on apoptosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Ann Hematol. 2010;89(11):1115–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00277-010-0988-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]