Abstract

Ethically challenging clinical situations are frequently encountered in neonatal and perinatal medicine (NPM), resulting in a complex environment for trainees and a need for ethics training during NPM residency. In the present study, the authors conducted a brief environmental scan to investigate the ethics teaching strategies in Canadian NPM programs. Ten of 13 (77%) accredited Canadian NPM residency programs participated in a survey investigating teaching strategies, content and assessment mechanisms. Although informal ethics teaching was more frequently reported, there was significant variability among programs in terms of content and logistics, with the most common topics being ‘The medical decision making process: Ethical considerations’ and ‘Review of bioethics principles’ (88.9% each); lectures by staff or visiting staff was the most commonly reported formal strategy (100%); and evaluation was primarily considered to be part of their overall trainee rotation (89%). This variability indicates the need for agreement and standardization among program directors regarding these aspects, and warrants further investigation.

Keywords: Ethics, Medical education, Neonatal perinatal medicine, Postgraduate, Teaching

Abstract

On affronte souvent des situations cliniques difficiles sur le plan éthique en médecine néonatale et périnatale (MNP), qui se traduisent par un milieu complexe pour les stagiaires et par la nécessité de donner une formation en éthique pendant la résidence en MNP. Dans la présente étude, les auteurs ont mené un bref examen du milieu pour examiner les stratégies d’enseignement de l’éthique au sein des programmes de MNP canadiens. Dix des 13 programmes de résidence canadiens agréés en MNP (77 %) ont participé à un sondage sur les stratégies d’enseignement, le contenu et les mécanismes d’évaluation. Même si l’enseignement informel de l’éthique était signalé davantage, on constatait une importante variabilité entre les programmes en matière de contenu et de logistique, les sujets les plus fréquents étant « Le processus de prise de décision médicale : des considérations éthiques » et « Examen des principes bioéthiques » (88,9 % chacun), les conférences données par le personnel ou du personnel en visite étaient la stratégie officielle la plus courante (100 %) et l’évaluation était principalement considérée comme un élément de la rotation globale des stagiaires (89 %). Cette variabilité démontre que les directeurs de programmes doivent s’entendre et standardiser ces aspects de l’éthique, et elle justifie des examens plus approfondis.

The relative high mortality and morbidity rates, prognostic uncertainty, medical and technological innovations to sustain life, and high parental expectations are among the reasons that may explain why ethically challenging clinical scenarios are frequently encountered in neonatal and perinatal medicine (NPM). This highly complex environment requires graduated NPM physicians to develop exceptional professionalism competencies with strong ethics knowledge, while being able to respectfully communicate with the parents to achieve decisions made by consensus through a shared decision-making process. These decisions are particularly significant, potentially involving lifelong consequences for these babies and their parents (1).

Formal ethics training during an NPM residency is necessary to support the potential disparate life experiences and ethics education background of trainees, and to equip them with ethics knowledge and the relational skills, including communication skills, to address the ethically challenging clinical situations specific to neonatology (2). Although the topic of ethics in medical education has gained increasing attention during the past decade, the literature regarding ethics training in NPM is sparse. Several publications primarily describe the content and logistics of the teaching program (2,3). Furthermore, others have highlighted the specific deficits in communication skills, particularly in ethically challenging scenarios, with one study that surveyed >100 graduating NPM fellows in the United States demonstrating that fellows believed that they were highly trained in the technical skills necessary to care for critically ill and dying infants, but inadequately trained in the communication skills needed for emotionally and ethically challenging situations. Overall, 41% of the trainees stated that they had no formal training in the communication skills needed to guide family decision making for high-risk newborns. The results of this study highlight the need for improvement in teaching communication and ethics in NPM residency programs (4).

In addition, the observation that professional communication with parents in these ethically challenging scenarios was not formally taught through the University of Ottawa (Ottawa, Ontario) NPM residency program, and the publication of the NPM training objectives from the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) in 2007 (5), prompted local academic neonatologists to adapt their residency training program (6). The establishment of the competency-driven CanMEDs roles and their reflection in the 2007 RCPSC NPM training objectives led the Canadian NPM residency program directors to review how ethics teaching was performed. Because the literature was not helpful to guide any necessary changes, the essential first step was to conduct an environmental scan, and investigate the context, ethics teaching strategies and norms in other Canadian NPM residency programs. To accomplish this first step, we conducted a national survey to examine the residency programs in Canada teaching (either formally or informally) neonatal ethics. We were also interested in the type and breadth of teaching strategies used, the variety of topics covered and the methods of assessment.

METHODS

A cross-sectional survey, based on similar work by Oljeski et al (7) that investigated radiology residency programs, was used. Some of the questions were modified to reflect the unique characteristics of NPM residency programs. Survey domains and response options originated from the aforementioned study, the literature regarding important topics in neonatal ethics, educational strategies not addressed in the previous study, and the direct experiences of the authors and their colleagues. Several local NPM experts assessed all questions for content validity. The finalized survey consisted of nine multiple-choice questions and focused on the following domains: teaching strategies; topics covered; assessment mechanisms; and teaching program logistics (Appendix 1). The questionnaire specifically inquired about informal teaching, which the authors defined as including impromptu discussions without specified learning objectives, and formal teaching, which was defined as structured teaching with clear learning objectives. With regard to assessment mechanisms, formative assessments were distinguished from summative assessments. Formative assessments occur while the trainee is in the process of some activity, thus facilitating real-time feedback (eg, portfolio systems, reflection or problem-based learning) (8). Summative assessments occur at the conclusion of an activity to assess overall performance and determine the extent to which the learning objectives have been met (eg, via a standardized test, rotation evaluation or other measure) (8,9).

From the RCPSC website, a total of 13 accredited Canadian NPM residency programs were identified (10). In February 2012, the survey was distributed by e-mail to all program directors of the NPM centres, followed by person-to-person contact by a member of the research team.

The Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Ethics Board (Ottawa, Ontario) approved the present study. Participation was voluntary and answering the questionnaire implied consent, as described in the invitation letter sent by e-mail.

Analysis

The survey results were analyzed using SPSS version 20 (IBM Corporation, USA). Frequencies and descriptive statistics were examined for each domain.

RESULTS

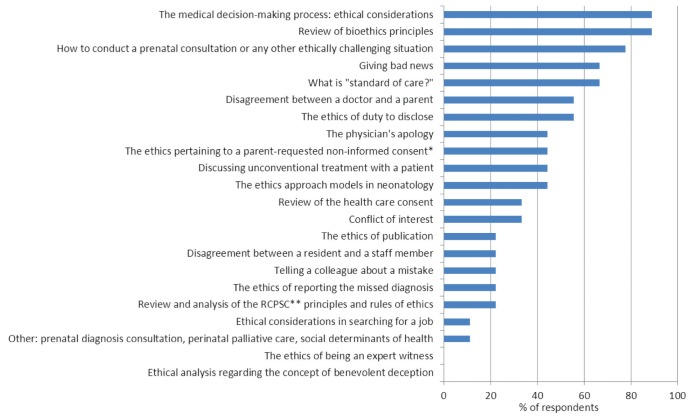

Ten of 13 program directors responded to the survey, yielding a response rate of 77%. The responses identified that ethics education was incorporated in nine programs (90%), both formally and informally. Figure 1 presents a summary of current ethics teaching strategies in Canadian NPM residency programs and summarizes the main teaching strategies used by the centres (centres are labelled from A to J) as well as the approximate number of hours devoted to teaching ethics per year. Excluding one NPM program (centre J) that reported not having any well-defined ethics residency education program, on average, the time devoted per year in informal ethics teaching was 10 h to 20 h (range: 10 h to 20 h, to >40 h), higher than the average reported time spent in formal ethics teaching (5 h to 10 h; range 5 h to 10 h, to >40 h). In addition, although informal ethics teaching was incorporated in their NPM residency program, one respondent (centre F) commented that it was difficult to appreciate the exact time devoted and could not specify the number of hours spent informally teaching ethics.

Figure 1).

Summary of current ethics teaching strategies in Canadian neonatal and perinatal medicine (NPM) programs. *Canadian NPM centres offering an optional degree in bioethics. SP Standardized patient

For the nine centres with an ethics residency education program, the main formal teaching strategies used were lectures by staff or visiting staff (100%) and case presentation either by residents or staff (67%) (Figure 1). Three of the nine (33%) centres used standardized patients (SPs) as part of their teaching strategies. Only one centre (11%) incorporated a portfolio to promote self-reflection. Interestingly, two centres (22%) offered an optional Master’s or Doctorate degree in bioethics.

Regarding informal teaching strategies, all nine centres indicate that they use discussion during neonatal intensive care unit rounds about cases, and discussion along with an antenatal consultation or ethically challenging clinical situation. Other informal teaching strategies highlighted by respondents were discussion during morbidity and mortality rounds.

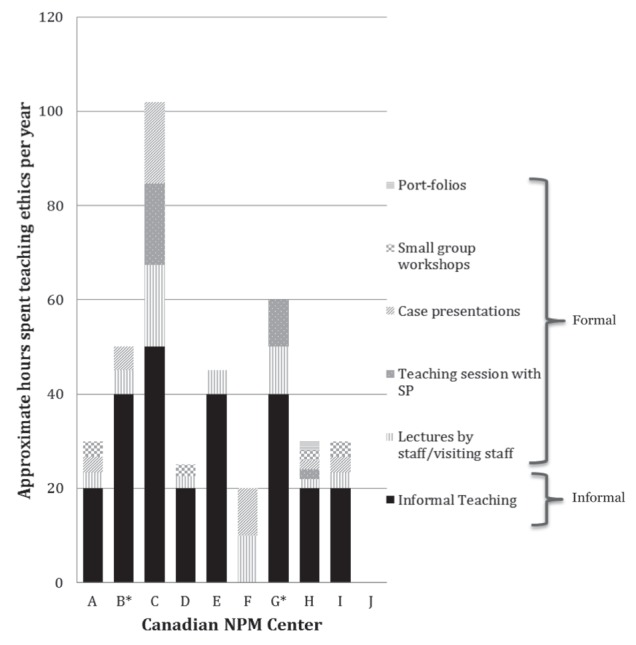

Ethics teaching in these different NPM residency programs encompasses a wide distribution of topics. Figure 2 provides a complete breakdown of topics covered. Participants’ programs most commonly cover the following topics: a review of bioethics principles; ethical consideration of medical decision making; how to conduct an antenatal consultation or how to approach other ethically challenging clinical scenario; what is ‘standard of care’; and communicating bad news.

Figure 2).

Topics covered in formal ethics teaching. *Includes parents who did not wish to participate in the decision-making process. **RCPSC Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

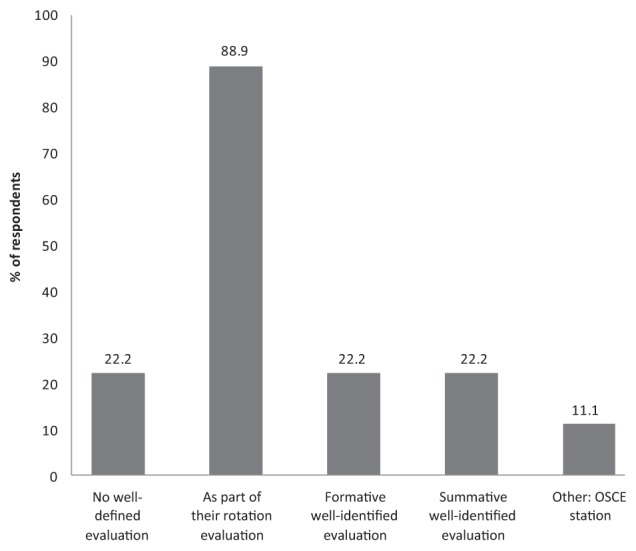

Program directors indicated that the assessment of their trainees for ethical competencies is primarily part of their rotation evaluation (89%) rather than a clearly defined process (Figure 3). There were no well-defined formative or summative assessments of the NPM residents’ ethical competencies during their training in the majority of NPM training program, and one centre indicated that they had no specific assessment tools.

Figure 3).

Evaluation format of trainees’ competency in ethics. OSCE Objective structured clinical examination

In six of the programs (67%), a designated neonatologist was responsible for ethics education; of those programs, most of these individuals (83%) had special training such as a Master’s degree (n=2) or a Doctorate degree (n=3) in ethics or equivalent. Respondents indicated that neonatologists and ethicists were the individuals primarily involved in teaching ethics; other teachers included social workers, nurses or palliative care specialists.

DISCUSSION

Our study revealed that the majority of Canadian NPM residency programs are fulfilling their mandate according to the RCPSC requirement for teaching medical ethics by using a variety of educational strategies (5). Only one of the 10 programs that responded did not have any well-identified teaching with regard to the ethics objectives included in their program.

Not surprisingly, informal teaching was the main teaching strategy used by the NPM residency programs. However, over-reporting the number of hours devoted to this type of ethics education is possible. The difficulties in assessing the number of hours spent (especially in informal teaching) make it difficult to draw any precise conclusion other than a description of an important variation among Canadian NPM residency programs. In addition, the topics covered and the teaching strategies used were inconsistent among centres.

With regard to topics covered, almost all centres cover bioethics principles and ethical consideration in the medical decision-making process. Beyond these topics, there is little uniformity; however, a number of topics (eg, conflicts of interest, giving bad news, disagreement between physician and parents) would be beneficial to all residents in Canadian NPM programs. These topics heavily involve communication skills, raising the question of how best to teach these skills.

Lectures and case presentations were the main formal teaching strategies. The nine centres reported using different teaching tools to support their formal ethics curriculum including small group workshops, teaching sessions involving SPs, self-reflection, videos or websites, and interdisciplinary sessions (available on request).

These findings highlight the lack of standardization with regard to teaching medical ethics among NPM centres including the time devoted to teaching ethics, the teaching tools used and the topics covered. This observed variability could be explained by the existence of multiple schools of thought in ethics and associated teaching traditions, but indicates the need for agreement among program directors regarding ethics content in NPM education and the logistics of this teaching, particularly in terms of teaching strategies.

We support many of the recommendations proposed in the literature, particularly those by Salih et al (2) and Boss et al (4), who argue for incorporating a formal ethics course into NPM fellowship programs and for education that extends beyond the content of bioethical principles and ethical reasoning to include communication skills, respectively (11,12). Lectures and seminars have been shown to be insufficient for trainees to learn and improve communication skills (12). More complex and comprehensive teaching tools to support their learning these skills are needed (11,12). To specifically teach communication skills, using an SP has demonstrated promise in the literature (13,14). Only three NPM centres use this teaching tool. SPs are beneficial for objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) or ‘practice OSCEs’ which, in turn, promote better communication skills from NPM residents in these difficult, ethically charged clinical situations.

Our survey identified an additional weakness: the lack of a well-founded, ubiquitous assessment strategy. Of the NPM program directors who indicated that assessing their trainees was part of the rotation evaluation, only two centres had integrated such a rigorous formative and summative approach for their trainees with regard to ethics-related competencies. Interestingly, one program included annual OSCEs, which is a strategy also recommended in the literature (15–17).

Our survey provides insight into how Canadian NPM residency programs incorporate the RCPSC NPM training objectives. It also brings to the forefront of discussion how best we can teach ethics in NPM and what improvements should be made. Although a larger sample to draw from would have been beneficial from a statistical perspective, there are only 13 NPM centres in Canada. The response rate of 77% in the present study provides a relatively representative illustration of what is happening in Canada. Response bias was another limitation because only program directors participated in the survey. Trainees’ opinions and responses would potentially provide different and interesting information regarding their learning experiences. Furthermore, we also recognize the limits of survey methodology in permitting nuanced answers to the questions.

These findings warrant a detailed examination and understanding of the aggregate experiences of program directors of Canadian NPM programs to establish agreement and standards on how to teach ethics in NPM medicine; future investigations may involve more qualitative components, such as interviews, to gain a more in-depth description of the unique circumstances in each centre and to acknowledge where a full needs assessment is justified. Because dealing with ethical situations is a daily occurrence for neonatologists, Canadian NPM residency programs and future neonatologists would benefit from a shared standardized curricula and assessment tools.

APPENDIX 1. SURVEY OF MEDICAL ETHICS TEACHING FOR NEONATOLOGY RESIDENTS IN CANADA

Please, indicate the name of your University:

❑ University of Calgary

❑ University of Laval

❑ Dalhousie University

❑ McGill University

❑ McMaster University

❑ Sunnybrook University

❑ University of Alberta

❑ British Columbia University

❑ University of Calgary

❑ University of Laval

❑ University of Manitoba

❑ University of Montreal

❑ University of Ottawa

❑ University of Toronto

❑ University of Saskatchewan

❑ University of Western Ontario

❑ Other: ___________

Please complete the following questions:

- Currently, is there any well-defined teaching of medical ethics part of your neonatology residency curriculum? (Please, choose only one answer)

- ❑ No, there is no well-defined program (End of survey. Thank you for your participation)

- ❑ Yes, there is only formal teaching (Answer the Formal Teaching Program Section)

- ❑ Yes, there is a formal and informal teaching (Answer the Formal and Informal Teaching Program Sections)

- ❑ Yes, there is only informal teaching without well-defined formal teaching (Go to Informal Teaching Program Section)

- What does your formal teaching consist of? (You may answer more than one, if applicable)

- ❑ Lectures or seminars by staff

- ❑ Lectures or seminars by visiting staff

- ❑ Videotape

- ❑ Electronic or Website tools

- ❑ Small group workshops

- ❑ Teaching sessions with standardized patients

- ❑ Case presentation by the residents

- ❑ Case presentation by staff

- ❑ Portfolio or self-reflection guide

- ❑ One-to-one mentoring

- ❑ Optional Master or PhD in Bioethics

- ❑ Formal Master or PhD in Bioethics

- ❑ Interdisciplinary teaching sessions

- ❑ Other (Please elaborate): ___________________________

- How many hours per year do you estimate that your residents spend in formal ethics education?

- ❑ Less than 5 hours

- ❑ 5 to 10 hours

- ❑ 10 to 20 hours

- ❑ 20 to 40 hours

- ❑ More than 40 hours

- ❑ Other (Please describe): ____________________________

- Which of these ethics topics are currently discussed in your formal ethics teaching? (You may answer more than one, if applicable)

- ❑ What is “standard of care”?

- ❑ Review of the bioethics principles

- ❑ The ethics approach models in neonatology (statistical, informative, individual, etc.)

- ❑ Giving bad news

- ❑ Conflict of interest

- ❑ Discussing unconventional treatment with a patient

- ❑ The medical decision-making process: ethical considerations

- ❑ Review of the health care consent (legislation in regard of health care)

- ❑ How to conduct a prenatal consultation or any other ethically challenging clinical situation

- ❑ The ethics pertaining to a parent-requested non-informed consent

- ❑ Review and analysis of the Royal College of Physician and Surgeon of Canada principles and rules of ethics

- ❑ The ethics of reporting the missed diagnosis

- ❑ Ethical analysis regarding the concept of benevolent deception

- ❑ The ethics of duty to disclose

- ❑ The physician’s apology

- ❑ Telling a colleague about a mistake

- ❑ Disagreement between a resident and a staff member

- ❑ Disagreement between a doctor and a parent

- ❑ The ethics of publication

- ❑ The ethics of being an expert witness

- ❑ Ethical considerations in searching for a job

- ❑ Other (Please describe): ____________________________

- What does your informal teaching consist of? (You may answer more than one, if applicable)

- ❑ Informal discussion during the rounds at the NICU

- ❑ Informal discussion along with the prenatal consultation or ethically challenging clinical situation

- ❑ Informal discussion in any other situations

- ❑ Other (Please elaborate): ___________________________

- How many hours per year do you estimate that your residents spend in informal ethics education?

- ❑ Less than 5 hours

- ❑ 5 to 10 hours

- ❑ 10 to 20 hours

- ❑ 20 to 40 hours

- ❑ More than 40 hours

- ❑ Other (Please describe): ____________________________

- How do you evaluate the trainees’ for their competencies in ethics? (You may answer more than one, if applicable)

- ❑ No well-defined evaluations

- ❑ As part of their rotation evaluation

- ❑ Formative well-identified evaluation

- ❑ Summative well-identified evaluation

- ❑ Other (Please elaborate): ___________________________

- Who is involved in the teaching in ethics in your NPM program? (You may answer more than one, if applicable)

- ❑ Neonatologist

- ❑ Lawyer

- ❑ Ethicist (if different that the neonatologist)

- ❑ Social worker

- ❑ Nurse

- ❑ Other (Please describe): ___________________________

- Have you designated a person responsible for the ethics curriculum in your program?

- ❑ No

- ❑ Yes

- a. Is this person a neonatologist?

- ❑ No

- ❑ Yes

- b. Does this person have any special training in ethics?

- ❑ No

- ❑ Yes (Please describe): ______________________________

END OF SURVEY

THANK YOU FOR YOUR PARTICIPATION!

REFERENCES

- 1.Catlin A. Extremely long hospitalizations of newborns in the United States: Data, descriptions, dilemmas. J Perinatol. 2006;26:742–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salih ZN, Boyle DW. Ethics education in neonatal-perinatal medicine in the United States. Semin Perinatol. 2009;33:397. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis DJ, Doucet H. A curriculum for teaching clinical ethics in neonatal-perinatal medicine. Ann R Coll Physicians Surg Can. 1996;29:45–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boss RD, Hutton N, Donohue PK, Arnold RM. Neonatologist training to guide family decision making for critically ill infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:783–8. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.RCPSC. Objectives of training in neonatal-perinatal medicine. Updated 2007. <www.medicine.mcgill.ca/postgrad/accreditation_2013/PSQs/2_Neonatal_Perinatal_Medicine/05_OTR_Neonatal_Perinatal_Medicine_2007.pdf> (Accessed October 30, 2013).

- 6.Daboval T, Moore GP, Ferretti E. How we teach ethics and communication during a Canadian neonatal perinatal medicine residency: An interactive experience. Med Teach. 2013;35:194–200. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.733452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oljeski SA, Homer MJ, Krackov WS. Incorporating ethics education into the radiology residency curriculum: A model. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:569–72. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.3.1830569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rushton A. Formative assessment: A key to deep learning? Med Teach. 2005;27:509–13. doi: 10.1080/01421590500129159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newble D, Cannon R. A handbook for medical teachers. 4th edn. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.RCPSC. Neonatal-perinatal medicine: Program directors. <www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/credentials/accreditation/arps/specialty/neonatal_perinatal> Updated 2011. (Accessed February 2012)

- 11.Cross KP. New lenses on learning. About Campus. 1996;1:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chickering AW, Gamson ZF. Development and adaptations of the seven principles for good practice in undergraduate education. New Dir Teach Learn. 1999;80:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:453–60. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaidya VU, Greenberg LW, Patel KM, Strauss LH, Pollack MM. Teaching physicians how to break bad news: A 1-day workshop using standardized parents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:419–22. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, et al. Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: The Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004;79:495–507. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yedidia MJ, Gillespie CC, Kachur E, et al. Effect of communications training on medical student performance. JAMA. 2003;290:1157–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional context. JAMA. 2002;287:226–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]