Abstract

Damage to the adult mammalian heart is irreversible, and lost cells are not replaced through regeneration. In neonatal mice, prior to P7, heart tissue can be regenerated after injury; however, the factors that facilitate cardiac regeneration in the neonatal heart are not known. In this issue of the JCI, Aurora and colleagues evaluated the immune response following myocardial infarction in P1 mice compared with that in P14 mice, which have lost their regenerative capacity, and identified a population of macrophages as mediators of cardiac repair. Further understanding of the immune modulators that promote the regenerative properties of this macrophage subset could potentially be exploited to recapitulate regenerative function in the adult heart.

Repair without regeneration in the damaged adult heart

Myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as heart attack, results in the loss of around 1 billion heart muscle cells and destruction of surrounding blood vessels. Once damaged, adult heart cells cannot be replaced through regeneration; therefore, an alternate form of wound healing is orchestrated by the immune system. Inflammatory cells migrate to the injured heart, ensuring the clearance of harmful cell debris and repair of the damaged area via formation of a fibrotic scar. The MI-associated inflammatory response is largely stereotypical and considered to be a function of the innate immune system. While inflammatory tissue reparation is initially beneficial, the scarring leads to pathological remodeling of the heart and compromised cardiac function over time. Moreover, if the initial acute inflammatory response becomes chronic, host tissue will be subject to continued damage.

Efforts to promote heart regeneration have largely centered on mechanisms to replace lost cardiovascular cells via cell transplantation or through stimulation of resident cells, such as altering progenitor cell differentiation or inducing muscle cell division. Relatively little attention has been paid to the local environment that transplanted or newly stimulated cells encounter in the heart following MI, which constitutes a proinflammatory milieu, much of which is cytotoxic, and an ensuing fibrosis that disrupts essential matrix. Together, the proinflammatory environment along with a dysfunctional matrix prevent engraftment and integration of new cells into survived heart tissue. While the default immune response to MI appears to ensure a quick fix of the heart, it precludes cell replacement and tissue regeneration.

Macrophage influx in cardiac wound healing and regeneration

In this issue of JCI, Aurora and colleagues (1) exploited the remarkable ability of the neonatal mouse heart to completely regenerate following injury in the first week of life (2) to study inflammation in heart repair. Aurora et al. focused on monocytes and their activated derivatives, macrophages. In adult animals, monocytes are the dominant cell infiltrate involved in healing injured myocardium within the first two weeks after injury. Monocytes arise from reservoirs in the bone marrow and spleen, alongside a further subpopulation resident within the tissue itself. When mobilized into the circulation, monocytes patrol blood vessels and respond to chemokines released from the injured tissue to infiltrate and differentiate irreversibly into macrophages (3). Once differentiated, macrophages are capable of engulfing dying cells at the site of injury; however, they release proteolytic enzymes and reactive oxygen species, which harm surviving cells and exacerbate the injury. While it appears that macrophages may do more harm than good in tissue repair, prevention of macrophage infiltration into the injured myocardium negatively correlates with healing and heart function. Seminal work by Nahrendorf and colleagues (4) reconciled this apparent conflict by revealing a biphasic wave of recruitment of subsets of monocytes and macrophages to the injured heart. The biphasic response is comprised of an early influx of proinflammatory monocytes, defined as Ly-6Chi (M1), which promote digestion of infarcted tissue and removal of necrotic debris, followed by infiltration of reparative Ly-6Clo (M2 or alternatively activated) monocytes, which propagate repair through collagen scar formation and coronary angiogenesis during the resolution of inflammation (3). A dual requirement for both M1 and M2 monocyte subsets is further emphasized by observations made when monocytes are depleted or elevated. Splenectomized mice, monocyte-depleted mice (4–6), and patients on steroids that reduce monocyte number (7) exhibit impaired wound healing following MI. Patients with elevated monocytosis (8, 9) and apolipoprotein E–null (ApoE-null) mice, which also have enhanced monocyte levels (10) also exhibit reduced MI-associated wound healing. Together, these data suggest that timely resolution of the inflammatory infiltrate and spatial constraint of the reparative response to the site of injury are essential for optimal healing following cardiac injury (11).

It is well established that monocytes and macrophages are essential for repairing MI-induced damage; however, the contribution of these cells in cardiovascular regeneration has not been appreciated. Aurora and colleagues profiled monocyte-derived populations in the hearts and spleens of mice that had undergone MI at P1, an age at which the neonatal heart can regenerate, or MI at P14, an age at which regenerative capacity is lost and replaced by scar formation (1). Aurora et al. observed an overall decrease in heart and splenic macrophages 7 days after MI in P1 mice compared with P14 mice. Furthermore, macrophages localized to the heart at different times, depending on the age of the animal at the time of MI. In P1 mice, macrophages were more abundant and distributed uniformly throughout the heart following MI, while in P14 mice, macrophages were fewer in number and localized almost exclusively to the site of injury (infarct zone) after MI. These data suggest a global macrophage response in P1 mice following injury. In adult zebrafish, which are able to regenerate heart tissue, other organ-wide events, including epicardial activation and cardiomyocyte proliferation, are observed during heart repair (12, 13). The significance of an organ-wide macrophage response to injury in the murine neonatal heart and the molecular cues that instruct localization to remote myocardium are unclear.

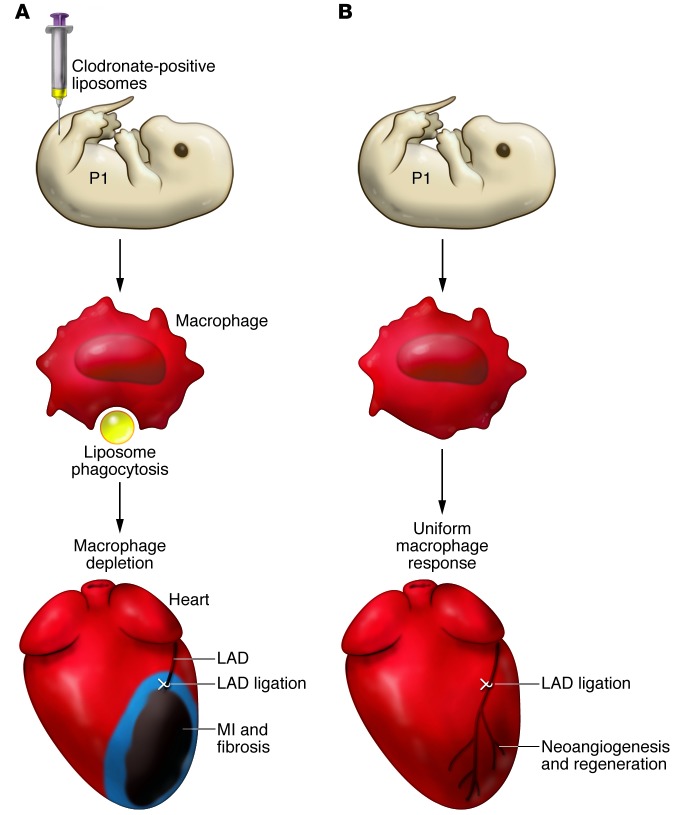

Based on the observed differences in macrophage responses in P1 mice and P14 mice following MI, Aurora and colleagues hypothesized that differences in abundance and localization might reflect a regenerative role for macrophages in mice undergoing MI at P1 (1). The importance of macrophages in P1 mouse heart regeneration was then tested directly by depleting them with clodronate-loaded liposomes prior to MI (14) (Figure 1). Strikingly, macrophage-depleted P1 mice could not regenerate heart tissue following MI and instead developed cardiac scarring accompanied by reduced cardiac function (Figure 1). Evaluation of neutrophils in P1 mice and P14 mice after MI revealed no differences in this immune cell population. Furthermore, despite the phagocytic property of neutrophils, clodronate liposome depletion appeared to be macrophage specific, likely due to the rapid and short-lived neutrophil response (11). It remains to be determined whether neutrophils contribute to heart regeneration.

Figure 1. Macrophage depletion prevents regeneration of the neonatal mouse heart.

(A) Neonatal mouse pups are intravenously injected with clodronate-loaded liposomes (yellow), which are phagocytosed by macrophages (red). Clodronate uptake results in macrophage apoptosis and subsequent depletion (blue). Loss of macrophages in neonatal mice results in scarring and fibrosis following MI. (B) In untreated pups, macrophages infiltrate the injured heart and are distributed uniformly throughout the heart (red) following MI. Macrophage infiltration into the heart is proposed to stimulate coronary neovascularization, via paracrine secretion of proangiogenic factors, to support myocardial regeneration. LAD, left anterior descending artery.

A unique macrophage population promotes neonatal cardiac regeneration

Transcriptional profiling revealed striking differences in gene expression between monocyte populations isolated from P1 mice following MI and monocyte populations isolated from P14 mice following MI. Analysis of candidate markers of both M1 (Cd86, Fcgr1, and Nos2) and M2 (chitinase-like 3 [Chi3l3] and arginase 1 [Arg1]) subtypes revealed that there was only a modest increase in candidate marker expression and no clear bias toward an M1 or an M2 response following MI in P1 mice; however, all markers were elevated in the monocyte population isolated from P14 mice after MI, including a substantial increase in the M2 marker Arg1. Subsequent microarray analysis revealed upregulation of transcripts involved in inflammation, angiogenesis, and oxidative stress in macrophages in P1 mice after MI, while following MI in P14 mice, the antiinflammatory factor Il10 was upregulated. Interestingly, monocyte populations from either P1 or P14 mice could not be definitively categorized as M1 or M2, suggesting that the canonical adult monocyte populations are not involved in neonatal responses to MI. Investigation of the cellular effects within the regenerating myocardium revealed that cardiomyocyte proliferation, which underpins myocardial repair (2), was unaffected in P1 mice that had been depleted of macrophages prior to MI; however, neovascularization, which restores blood flow to ischemic and newly formed myocardium, was impaired, suggesting that P1 macrophages promote coronary angiogenesis.

Conclusions and future directions

A general role for macrophages in tissue regeneration is evident across multiple species. In the axolotl, an aquatic salamander, macrophages are required during the early phase of limb regeneration (15), suggesting an evolutionary conservation of regenerative macrophages from amphibians to mammals. However, since the axolotl is neotenic, an essentially juvenile form, it will be interesting to extrapolate the requirement for macrophages in juvenile tissue regeneration to an adult model of heart regeneration, such as the zebrafish.

A number of important questions remain regarding the role of macrophages in neonatal mouse heart regeneration. Monocytes represent a heterogeneous mix in the adult heart based on immune phenotypes, proinflammatory versus antiinflammatory status, and reparative profiles (16). Aurora and colleagues attempted to stratify the neonatal populations according to the well-described M1 and M2 subtypes, but it is apparent that the macrophage population derived from P1 neonates following MI represents a distinct and unique subset: therefore, this macrophage population likely performs different functions compared with macrophages isolated from P14 and adult mice after injury (1). Due to the distinct characteristics of the regenerative macrophages identified in P1 mice, translating the findings of Aurora and colleagues for targeting monocytes/macrophages during adult heart injury will be complex moving forward. Additionally, the mechanisms used by the P1 regenerative macrophage subset to promote regeneration are unclear, although a proangiogenesis function was implicated. It is possible that regenerative macrophages act on resident fibroblast and myofibroblast populations, which mediate fibrosis and scarring after MI; however, these interactions have not been explored. Interestingly, recent evidence indicates cross talk between macrophage and stem cell populations (17), which could contribute to neonatal mouse heart regeneration (2, 18).

The signals required to reprogram adult macrophages or induce a biphasic recruitment of subtypes into the infarcted adult heart remain unknown. It is also unclear how the transition from the P1 regenerative phenotype to an immunophenotype is regulated and which injury-induced factors are involved. Interestingly, Aurora and colleagues found that Tregs at P1 were largely undetectable, only emerging after P4 (1). Given that Tregs promote monocyte differentiation toward an antiinflammatory/reparative profile (19), the lymphocyte response may induce the immuno-switch in macrophages beyond P1.

Aurora and colleagues profiled changes in absolute numbers of heart and splenic macrophages in P1 and P14 mice after MI (1); however, due to the global macrophage depletion by clodronate, the source of regenerative macrophages was not determined. Macrophages that localize to the heart following injury could infiltrate via the circulation from remote sources, such as bone marrow, or progenitors seeded in hemogenic endothelium and yolk sac blood islands or derive from local precursors in the heart (16). Macrophages that originate from sources other than bone marrow and spleen do not necessarily confer inflammatory functions, but in the adult heart, tissue macrophages (CX3CR1+) are the predominant form in the myocardium and resemble the alternatively activated antiinflammatory M2 macrophages (20). Whether an equivalent resident population resides in the neonatal heart remains to be determined.

Despite outstanding questions, the finding that macrophages are required for heart regeneration is very compelling and potentially paradigm shifting. Although more work will be required to recapitulate regenerative macrophage function in the adult heart, targeting immunomodulation following MI, along with cell-based regenerative therapies, has potential for optimal cardiovascular repair.

Acknowledgments

P.R. Riley is a British Heart Foundation Professor of Regenerative Medicine, supported by BHF grants: CH/11/1/28798 and RG/13/9/30269.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author has declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Citation for this article: J Clin Invest. 2014;124(3):961–964. doi:10.1172/JCI74418.

See the related article beginning on page 1382.

References

- 1.Aurora AB, et al. Macrophages are required for neonatal heart regeneration. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(3):1382–1392. doi: 10.1172/JCI72181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porrello ER, et al. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science. 2011;331(6020):1078–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1200708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nahrendorf M, Pittet MJ, Swirski FK. Monocytes: protagonists of infarct inflammation and repair after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;121(22):2437–2445. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.916346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nahrendorf M, et al. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med. 2007;204(12):3037–3047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swirski FK, et al. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325(5940):612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Amerongen MJ, Harmsen MC, van Rooijen N, Petersen AH, van Luyn MJ. Macrophage depletion impairs wound healing and increases left ventricular remodeling after myocardial injury in mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(3):818–829. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts R, DeMello V, Sobel BE. Deleterious effects of methylprednisolone in patients with myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1976;53(3 suppl):I204–I206. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.53.1.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsujioka H, et al. Impact of heterogeneity of human peripheral blood monocyte subsets on myocardial salvage in patients with primary acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(2):130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maekawa Y, et al. Prognostic significance of peripheral monocytosis after reperfused acute myocardial infarction: a possible role for left ventricular remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(2):241–246. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01721-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panizzi P, et al. Impaired infarct healing in atherosclerotic mice with Ly-6C(hi) monocytosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(15):1629–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frangogiannis NG. The immune system and cardiac repair. Pharmacol Res. 2008;58(2):88–111. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lepilina A, et al. A dynamic epicardial injury response supports progenitor cell activity during zebrafish heart regeneration. Cell. 2006;127(3):607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itou J, et al. Migration of cardiomyocytes is essential for heart regeneration in zebrafish. Development. 2012;139(22):4133–4142. doi: 10.1242/dev.079756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Rooijen N, van Nieuwmegen R. Elimination of phagocytic cells in the spleen after intravenous injection of liposome-encapsulated dichloromethylene diphosphonate. An enzyme-histochemical study. Cell Tissue Res. 1984;238(2):355–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00217308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godwin JW, Pinto AR, Rosenthal NA. Macrophages are required for adult salamander limb regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(23):9415–9420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300290110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity in the heart. Circ Res. 2013;112(12):1624–1633. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Mordechai T, et al. Macrophage subpopulations are essential for infarct repair with and without stem cell therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(20):1890–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jesty SA, et al. c-kit+ precursors support postinfarction myogenesis in the neonatal, but not adult, heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(33):13380–13385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208114109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tiemessen MM, Jagger AL, Evans HG, van Herwijnen MJ, John S, Taams LS. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce alternative activation of human monocytes/macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(49):19446–19451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706832104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinto AR, et al. An abundant tissue macrophage population in the adult murine heart with a distinct alternatively-activated macrophage profile. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e36814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]